Abstract

Background

Low birth weight is associated with an increased risk of developing chronic diseases in adulthood, with a particularly high incidence in Japan among developed countries. Maternal undernutrition is a risk factor for low birth weight, but the association between the timing of food intake and infant birth weight has not been investigated. This study aimed to examine the association between breakfast intake frequency among Japanese pregnant women and infant birth weight.

Methods

Of all pregnant women who participated in the Tohoku Medical Megabank Project Three Generation Cohort Study, 16,820 who answered the required questions were included in the analysis. The frequency of breakfast intake from pre- to early pregnancy and from early to mid-pregnancy was classified into four groups: every day and 5–6, 3–4, and 0–2 times/week. Multivariate linear regression models were constructed to examine the association between breakfast intake frequency among pregnant women and infant birth weight.

Results

The percentage of pregnant women who consumed breakfast daily was 74% in the pre- to early pregnancy period and 79% in the early to mid-pregnancy period. The average infant birth weight was 3,071 g. Compared to women who had breakfast daily from pre- to early pregnancy, those who had breakfast 0–2 times/week had lower infant birth weight (β = -38.2, 95% confidence interval [CI]: -56.5, -20.0). Similarly, compared to women who had breakfast daily from early to mid-pregnancy, those who had breakfast 0–2 times/week had lower infant birth weight (β = -41.5, 95% CI: -63.3, -19.6).

Conclusions

Less frequent breakfast intake before and mid-pregnancy was associated with lower infant birth weight.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Low birth weight is associated with an increased risk of neonatal death [1], stunting in childhood [2], and chronic diseases in adulthood [3]. An analysis of birth weight data from United Nations member states from 2000 to 2015 showed that while the overall low birth weight rate decreased from 17.5% to 14.6%, the low birth weight rate in Japan increased from 8.6% to 9.5% [4]. Thus, the continued increase in low birth weight in Japan is an anomaly by global standards and requires intervention.

Factors influencing the decline in infant birth weight include low maternal weight [5], low gestational weight gain [6], hypertensive disorders of pregnancy [7], and the mother’s diet during pregnancy [8,9,10,11]. This suggests that maternal health and lifestyle affect the development of the fetus.

In addition, since night shifts during pregnancy may be associated with birth weight [12], pregnant women’s irregular circadian rhythm may affect infant birth weight [13]. Normalization of circadian rhythms requires morning sun exposure and breakfast [14, 15]. Disruption of circadian rhythms by skipping breakfast negatively affects obesity, metabolic functions [16, 17], memory [18], and depressive symptoms [19]. However, in Japan, the rate of skipping breakfast among 20–30-year-olds is as high as 25.8% [20], and the National Nutrition Survey has reported that skipping breakfast is a factor that increases the risk of unbalanced nutrient intake [21]. Pregnant women have been shown to skip breakfast at a high rate of 20–30%, suggesting an association with reduced nutrient intake [22] and an increased risk of gestational diabetes [23]. Furthermore, the fetus may be influenced by the circadian rhythm of maternal food intake [24]. Since not only “what and how much” the pregnant women eat but also “when” they eat affect infant growth, we hypothesized that less frequent maternal breakfast intake would decrease infants’ birth weight. However, to our knowledge, no study has examined the association between maternal breakfast intake frequency and infant birth weight.

This study aimed to investigate the association between the frequency of breakfast consumption among pregnant women in Japan and infant birth weight.

Materials and methods

Study design and population

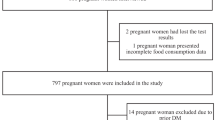

The data were used from the Tohoku Medical Megabank Project Birth and Three-Generation Cohort Study (TMM BirThree Cohort Study), the details of which are described elsewhere [25, 26]. Pregnant women and their families were recruited from 2013 to 2017 from obstetrics and gynecology clinics or hospitals where deliveries had been scheduled. Approximately 50 obstetrics and gynecology clinics and hospitals in the Miyagi Prefecture participated in the recruitment process. A total of 23,406 pregnant women were enrolled, of whom 514 withdrew from participation, 1,896 had missing data on the Food Intake Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ), 369 had a total energy intake in the highest or lowest 1st percentile (pre- to early pregnancy: < 605 or > 3828 kcal/day, early to mid-pregnancy: < 490 or > 3553 kcal/day), 49 had type 1 or 2 diabetes, 606 had multiple pregnancies, 24 had no medical record of birth weight, 1,042 had a preterm delivery, and 20 were excluded because of chromosomal abnormalities. Of the remaining 18,890 pregnant women, 2,070 were excluded because of missing covariates. Finally, the remaining 16,820 pregnant women were included in the analysis (Fig. 1). The TMM BirThree Cohort Study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Tohoku University Tohoku Medical Megabank Organization Ethics Committee (2013–1-103–1).

Exposure variables

Frequencies of breakfast and other food intake were assessed using the 130-item self-administered semi quantitative FFQ. The FFQ used in this study had the response option “constitutionally unable to eat or drink” [27], which was found in the modified version of the FFQ used in the Japan Public Health Center-Based (JPHC) study [28, 29]. Data on the breakfast intake frequency among pregnant women were obtained from the first and second FFQs, which were administered in early pregnancy (0–13 weeks of gestation) and mid-pregnancy (14–27 weeks of gestation), respectively. The first FFQ assessed the frequency and quantity of foods and beverages consumed in the past 1 year, while the second FFQ assessed those consumed since the administration of the first FFQ. The breakfast intake frequency was assessed using the question, “How often do you eat breakfast?”. Categories of intake frequency in the response items were: less than once a month, 1–3 times a month, 1–2 times a week, 3–4 times a week, 5–6 times a week, and every day. The first three categories were combined 0–2 times a week because of the small number of participants. First, total energy and nutrient intake were calculated using data from the Standard Tables of Food Composition in Japan (Fifth Revised and Enlarged Edition 2005) [30]. Then, each food and nutrient consumed was energy-adjusted using the residual method [31].

Outcome variables

Infant birth weight (g) was the outcome variable (continuous variable). Infant birth weight was obtained from birth records.

Potential covariates

Based on previous studies, the following covariates were selected [5, 8,9,10,11, 23]: age at birth, body mass index (BMI) before pregnancy, smoking status, alcohol consumption, morning sickness, parity, employment status, insomnia, child sex, gestational week, folic acid supplements, and intake of energy, cereal, meat, seafood, bean, vegetables, and fruits. Age at delivery was categorized into four groups: < 25, 25–29, 30–34, and ≥ 35 years. Before pregnancy, BMI was classified into three groups: < 18.5, 18.5–24.9, and ≥ 25.0 kg/m2. The smoking status was categorized into four groups: never-smoked, quit before pregnancy, quit after pregnancy, and currently smoking. Alcohol consumption was categorized into three groups: never, former, and current. Morning sickness was categorized into four groups: never, nausea only, able to eat with vomiting, and unable to eat with vomiting. The employment status was categorized as employed or unemployed. Insomnia was defined as a score ≥ 6 on the Japanese version of the Athens Insomnia Scale [32]. Intake of total energy, cereal, meat, fish, beans, vegetables, and fruits were calculated using FFQ.

The variance inflation factor was <1.2, which was considered to be noncollinear [33].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the analysis of variance for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables to examine differences in characteristics of pregnant women according to their breakfast intake frequency. The association between maternal breakfast intake frequency and infant birth weight was evaluated with the multivariate linear regression analysis to calculate the regression coefficient β, 95% confidence interval (CI), and p-value for trend. Three models were constructed to examine these associations. Model 1 was a crude model. Model 2 was adjusted for age at birth, BMI before pregnancy, smoking status, alcohol consumption, morning sickness, parity, employment status, insomnia, child sex, and gestational week. Model 3 was adjusted for model 2 and folic acid supplements, intake of energy, grains, meat, fish, beans, vegetables, and fruits. To assess the goodness of fit of the model, coefficients of determination were calculated. Additional analyses were conducted, including risk factors for low birth weight (type 1 or type 2 diabetes, multiple pregnancies, preterm birth, and chromosomal abnormalities). Futhermore, because low energy intake is a risk factor for low birth weight [34], we performed a stratified analysis using energy intake quartiles. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Statistical significance was set at a p-value < 0.05.

Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics of pregnant women and infants according to the breakfast intake frequency. The mean maternal age at birth was 31.3 ± 5.0 years. Frequencies of women who had breakfast daily were 74% and 79% in the pre- to early and early to mid-pregnancy periods, respectively. Compared to women who had breakfast every day, those who skipped breakfast more frequently had a lower age at delivery and higher rates of smoking, first childbirth, and insomnia. Women who skipped breakfast more frequently also had higher intakes of fat, vitamin A, niacin, vitamin B12, sugar, meat, confectionery, and alcoholic beverage (Supplementary Table 1). The mean infant birth weight was 3,071 ± 371 g.

Table 2 shows the association between frequency of breakfast intake and infant birth weight among pregnant women. Compared with women who consumed breakfast daily pre- to early pregnancy, the regression coefficients (95% CI) for infant birth weight for women who consumed breakfast 5–6, 3–4 and 0–2 times a week were -2.1 (-21.0, 16.9), -32.1 (-54.4, -9.9) and -26.9 (-46.6, -7.3) respectively ( Model 1). After adjusting for covariates, the regression coefficients (95% CI) were -14.5 (-31.5, 2.5), -45.0 (-65.1, -25.0), and -44.3 (-62.3, -26.3), respectively (Model 2). Furthermore, after adjusting for dietary intake, the regression coefficients (95% CI) were -12.4 (-29.4, 4.6), -41.7 (-61.9, -21.6), and -38.2 (-56.5, -20.0), respectively (Model 3). Compared with women who consumed breakfast daily early to mid-pregnancy, the regression coefficients (95% CI) for infant birth weight for women who consumed breakfast 5–6, 3–4 and 0–2 times a week were -5.0 (-24.5, 14.5), -18.3 (-42.4, 5.8) and -36.5 (-60.2, -12.9) respectively ( Model 1). After adjusting for covariates the regression coefficients (95% CI) were -12.5 (-32.2, 2.7), -38.1 (-59.8, -16.4), and -49.0 (-70.6, -27.3), respectively (Model 2). Furthermore, after adjusting for dietary intake, the regression coefficients (95% CI) were -12.2 (-29.7, 5.4), -33.6 (-55.4, -11.8), and -41.5 (-63.3, -19.6), respectively (Model 3). Less frequent breakfast intake from pre- to early pregnancy and from early to mid-pregnancy was associated with a dose-dependent decrease in infant birth weight in all models (all P for trend = < 0.001). The association between frequency of maternal breakfast intake and infant birth weight, including risk factors for low birth weight, was similar to that in the main analysis (Supplementary Table 2). The regression coefficients for variables other than frequency of breakfast intake have been included in Supplementary Table 3.

Table 3 shows the results of a stratified analysis to determine whether the association between maternal breakfast intake and infant birth weight varied by energy intake. Compared with mothers who consumed breakfast daily prepregnancy to early pregnancy, the adjusted β (95% CI) of infant birth weight for mothers who consumed breakfast 0–2 times per week were -26.7 (-55.9, 2.4), -23.5 (-62.6, 15.7), -47.3 (-88.3, -6.4), and -64.9 (-108.8, -21.0) in the first, second, third, and fourth energy intake quartiles, respectively. Adjusted β (95% CI) for infant birth weight for mothers who consumed breakfast 0–2 times per week from early pregnancy to midpregnancy were -23.5 (-57.3, 10.3), -25.6 (-72.5, 21.3), -51.8 (-101.9, -1.6), and -66.1 (-122.9, -9.2) in the first, second, third, and fourth energy intake quartiles, respectively.

Discussion

The present study showed that less frequent breakfast intake from pre- to mid-pregnancy was associated with lower infant birth weight. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the association between breakfast intake frequency among Japanese pregnant women and infant birth weight.

A few previous studies investigated breakfast intake among pregnant women. Pregnant Japanese women who skip breakfast consume significantly less protein, meat, and dairy products than those who eat breakfast daily [22]. These findings are consistent with the results of this study. Another Japanese study showed that pregnant women who skipped breakfast had a higher risk of developing gestational diabetes, suggesting that skipping breakfast may negatively affect glucose metabolism [23]. In a study on breakfast intake in adults, those who consumed breakfast daily had a lower risk of developing obesity, metabolic syndrome, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and stroke compared to those who consumed breakfast less frequently [35, 36], and this association did not change after adjusting for dietary quality scores [35]. The present study showed that a low breakfast intake frequency among pregnant women might affect their health for themselves and for two generations, which is a novel finding.

Three mechanisms are plausible, although we did not examine the mechanism by which the breakfast intake frequency among pregnant women affected infant birth weight. The first possible mechanism is that the circadian rhythm is disrupted when a pregnant woman skips breakfast, which affects the growth of the fetus. Regulation of correct circadian rhythms requires light stimulation from morning sun exposure and regular food intake [14, 37]. Skipping breakfast can disrupt circadian rhythms by affecting the expression of clock and clock-regulated genes [38]. In a study involving adults, the body clocks of the eliminating organs remained delayed when breakfast was skipped, even after waking up in the morning [15]. In a study involving students who were not habitual breakfast-eaters, the 24-h rhythms of the heartbeat and sympathetic nervous system advanced by 1–3 h, and triglyceride and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels decreased when breakfast was consumed for 2 weeks [39]. In addition, the fetus begins to form its internal clock at approximately 20 weeks of gestation, using the mother’s circadian rhythm as a model [24, 40]. Sleep-deprived women have a higher risk of preterm delivery [41], and women who work rotating shifts have increased risks of spontaneous abortion, preterm delivery, and low birth weight [42, 43]. The circadian rhythm of pregnant women who skip breakfast may affect that of the fetus, which in turn may affect the birth weight of the fetus.

The second possible mechanism is the effect of infrequent breakfast intake on reproductive function. Skipping breakfast in female college students was associated with dysmenorrhea because of reduced uterine blood flow [44,45,46]. In a study using mice, deletion in utero of the clock gene Bmal1, which regulates the circadian clock, caused perinatal abnormalities, such as placental abruption [47]. Women who skip breakfast may have disrupted reproductive rhythms and ovarian and uterine dysfunctions [48]. Thus, infrequent breakfast intake by pregnant women may be associated with poor blood flow to the uterus and placenta and decreased infant birth weight.

The third possible mechanism is that infrequent breakfast intake increases inflammatory biomarkers and reduces child growth. In a study involving Chinese adults, habitually skipping breakfast was associated with increased C-reactive protein levels [49]. Maternal chronic inflammation is a possible cause of low birth weight [50]. Therefore, infrequent breakfast intake may increase inflammation and decrease infant birth weight.

A previous study showed that skipping breakfast was associated with unhealthy eating habits [51]. The present study showed that mothers who skipped breakfast had lower energy and nutrient intakes. The association between lower frequency of breakfast consumption and lower infant birth weight was found in the second, third, and fourth quartiles of energy intake, both in the prepregnancy to early pregnancy and early pregnancy to midpregnancy periods. These findings suggest that skipping breakfast and eating more at lunch and dinner before and during midpregnancy may have an effect on reduced infant birth weight, independent of energy and nutrient intakes.

Implications

The results of this study suggest that increasing breakfast frequency from preconception to mid-pregnancy may increase infant birth weight. In Japan, the Dietary Guidelines for Pregnant Women Starting Before Pregnancy have been revised, highlighting the importance of improving dietary habits even before pregnancy [52]. However, despite the problem of the high rate of breakfast deprivation among young Japanese women, the dietary guidelines do not include any guidelines for breakfast intake. Therefore, for forming healthy eating habits, guidelines for eating behavior should be laid down [53], particularly for breakfast intake for pregnant women. Considering the results of this study, interventions focused on increasing the breakfast intake frequency before and in early pregnancy may be effective in preventing reduced infant birth weight.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, this study was conducted in a small part of Japan, and the results cannot be generalized to other populations. However, the average age of participants in a national survey of pregnant women in Japan was 31.0 years [54], and that of participants in this study was almost the same at 31.3 years. Second, because the data on skipping breakfast were obtained from participants’ self-reported questionnaires, misunderstandings regarding skipping breakfast would have arisen. However, the percentage of Japanese pregnant women who do not eat breakfast ranges from 20 to 30% [22, 23] and is similar to the percentage in this study (pre- to early pregnancy, 25.9%; early to mid-pregnancy, 21.0%). Third, the type and amount of food consumed for breakfast are unknown. To better examine the association between skipping breakfast and infant birth weight, the frequency of breakfast intake and the type, amount, and time of day of the meal should be examined. Fourth, skipping breakfast is influenced by various social backgrounds, such as night shifts and time availability. The covariates adjusted for this study may not fully eliminate the effects of these backgrounds. However, the proportion of pregnant women in Japan who work night shifts is as small as 7.7% [23]. Fifth, we did not measure circadian rhythms, such as waking and sleeping times.

Conclusion

Compared to daily breakfast intake, consuming breakfast less than 5 times a week from prepregnancy to midpregnancy was associated with lower infant birth weight. The pregnancy period is a good opportunity for mothers to review their nutritional status and change undesirable eating habits. Our finding suggests that breakfast intake before and during pregnancy may be important for the prevention of low birth weight.

Availability of data and materials

The TMM BirThree Cohort Study data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to them containing information that could compromise research participant consent. All inquiries about access to the data should be sent to the TMM (dist@megabank.tohoku.ac.jp).

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- FFQ:

-

Food frequency questionnaire

- TMM BirThree Cohort Study:

-

Tohoku Medical Megabank Project Birth and Three-Generation Cohort Study

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

References

Katz J, Lee ACC, Kozuki N, Lawn JE, Cousens S, Blencowe H, et al. Mortality risk in preterm and small-for-gestational-age infants in low-income and middle-income countries: a pooled country analysis. Lancet. 2013;382(9890):417–25.

Christian P, Lee SE, Angel MD, Adair LS, Arifeen SE, Ashorn P, et al. Risk of childhood undernutrition related to small-for-gestational age and preterm birth in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(5):1340–55.

Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Beedle AS. Early life events and their consequences for later disease: a life history and evolutionary perspective. Am J Hum Biol. 2007;19(1):1–19.

Blencowe H, Krasevec J, de Onis M, Black RE, An XY, Stevens GA, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of low birthweight in 2015, with trends from 2000: a systematic analysis. Lancet Global Health. 2019;7(7):E849–60.

Han Z, Mulla S, Beyene J, Liao G, McDonald SD, Knowledge SG. Maternal underweight and the risk of preterm birth and low birth weight: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(1):65–101.

Ehrenberg HM, Dierker L, Milluzzi C, Mercer BM. Low maternal weight, failure to thrive in pregnancy, and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(6):1726–30.

Poudel K, Kobayashi S, Miyashita C, Ikeda-Araki A, Tamura N, Bamai YA, et al. Hypertensive Disorders during Pregnancy (HDP), maternal characteristics, and birth outcomes among Japanese Women: a hokkaido study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(7):3342.

Morisaki N, Nagata C, Yasuo S, Morokuma S, Kato K, Sanefuji M, et al. Optimal protein intake during pregnancy for reducing the risk of fetal growth restriction: the Japan Environment and Children’s Study. Br J Nutr. 2018;120(12):1432–40.

Eshak ES, Okada C, Baba S, Kimura T, Ikehara S, Sato T, et al. Maternal total energy, macronutrient and vitamin intakes during pregnancy associated with the offspring’s birth size in the Japan Environment and Children’s Study. Br J Nutr. 2020;124(6):558–66.

Yonezawa Y, Obara T, Yamashita T, Sugawara J, Ishikuro M, Murakami K, et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption before and during pregnancy and birth weight of new-borns in Japan: the Tohoku Medical Megabank Project Birth and Three-Generation Cohort Study. Nutr J. 2020;19(1):80.

Yonezawa Y, Obara T, Yamashita T, Ishikuro M, Murakami K, Ueno F, et al. Grain consumption before and during pregnancy and birth weight in Japan: the Tohoku Medical Megabank Project Birth and Three-Generation Cohort Study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2022;76(2):261–9.

Bonzini M, Palmer KT, Coggon D, Carugno M, Cromi A, Ferrario MM. Shift work and pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review with meta-analysis of currently available epidemiological studies. BJOG. 2011;118(12):1429–37.

Kaur S, Teoh A, Shukri NHM, Shafie SR, Bustami NA, Takahashi M, et al. Circadian rhythm and its association with birth and infant outcomes: research protocol of a prospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):96.

Asher G, Sassone-Corsi P. Time for food: the intimate interplay between nutrition, metabolism, and the circadian clock. Cell. 2015;161(1):84–92.

Wehrens SMT, Christou S, Isherwood C, Middleton B, Gibbs MA, Archer SN, et al. Meal timing regulates the human circadian system. Curr Biol. 2017;27(12):1768–75.

Horikawa C, Kodama S, Yachi Y, Heianza Y, Hirasawa R, Ibe Y, et al. Skipping breakfast and prevalence of overweight and obesity in Asian and Pacific regions: a meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2011;53(4–5):260–7.

Deshmukh-Taskar P, Nicklas TA, Radcliffe JD, O’Neil CE, Liu Y. The relationship of breakfast skipping and type of breakfast consumed with overweight/obesity, abdominal obesity, other cardiometabolic risk factors and the metabolic syndrome in young adults. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES): 1999–2006. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(11):2073–82.

Loh DH, Jami SA, Flores RE, Truong D, Ghiani CA, O'Dell TJ, et al. Misaligned feeding impairs memories. Elife. 2015;4:e09460.

Lee YS, Kim TH. Household food insecurity and breakfast skipping: Their association with depressive symptoms. Psychiatry Res. 2019;271:83–8.

Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries: Policies for the Promotion of Shokuiku (White Paper on Shokuiku) The Fiscal Year 2019 Edition. https://www.maff.go.jp/j/syokuiku/wpaper/attach/pdf/r1_index-4.pdf. Accessed 8 Mar 2023

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare: Health Japan 21. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/www1/topics/kenko21_11/pdf/b1.pdf. Accessed 8 Mar 2023.

Shiraishi M, Haruna M, Matsuzaki M. Effects of skipping breakfast on dietary intake and circulating and urinary nutrients during pregnancy. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2019;28(1):99–105.

Dong JY, Ikehara S, Kimura T, Cui MS, Kawanishi Y, Ueda K, et al. Skipping breakfast before and during early pregnancy and incidence of gestational diabetes mellitus: the Japan Environment and Children’s Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;111(4):829–34.

Seron-Ferre M, Mendez N, Abarzua-Catalan L, Vilches N, Valenzuela FJ, Reynolds HE, et al. Circadian rhythms in the fetus. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;349(1):68–75.

Kuriyama S, Yaegashi N, Nagami F, Arai T, Kawaguchi Y, Osumi N, et al. The Tohoku Medical Megabank Project: Design and Mission. J Epidemiol. 2016;26(9):493–511.

Kuriyama S, Metoki H, Kikuya M, Obara T, Ishikuro M, Yamanaka C, et al. Cohort Profile: Tohoku Medical Megabank Project Birth and Three-Generation Cohort Study (TMM BirThree Cohort Study): rationale, progress and perspective. Int J Epidemiol. 2020;49(1):18-9m.

Takachi R, Ishihara J, Iwasaki M, Hosoi S, Ishii Y, Sasazuki S, et al. Validity of a self-administered food frequency questionnaire for middle-aged urban cancer screenees: comparison with 4-day weighed dietary records. J Epidemiol. 2011;21(6):447–58.

Sasaki S, Takahashi T, Iitoi Y, Iwase Y, Kobayashi M, Ishihara J, et al. Food and nutrient intakes assessed with dietary records for the validation study of a self-administered food frequency questionnaire in JPHC Study Cohort I. J Epidemiol. 2003;13(1):S23–50.

Tsugane S, Kobayashi M, Sasaki S. Validity of the self-administered food frequency questionnaire used in the 5-year follow-up survey of the JPHC Study Cohort I: comparison with dietary records for main nutrients. J Epidemiol. 2003;13(1):S51–6.

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology: Standard tables of food composition in japan fifth revised and enlarged edition −2005-(Japanese). https://www.mext.go.jp/b_menu/shingi/gijyutu/gijyutu3/toushin/05031802.htm. Accessed 8 Mar 2023.

Willett W, Stampfer MJ. Total energy intake: implications for epidemiologic analyses. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;124(1):17–27.

Okajima I, Nakajima S, Kobayashi M, Inoue Y. Development and validation of the Japanese version of the Athens Insomnia Scale. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;67(6):420–5.

Johnston R, Jones K, Manley D. Confounding and collinearity in regression analysis: a cautionary tale and an alternative procedure, illustrated by studies of British voting behaviour. Qual Quant. 2018;52:1957–76.

World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on antenal care for a positive pregnancy experience. 2016. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549912 Accessed 8 Mar 2023 .

Odegaard AO, Jacobs DR, Steffen LM, Van Horn L, Ludwig DS, Pereira MA. Breakfast frequency and development of metabolic risk. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(10):3100–6.

Kubota Y, Iso H, Sawada N, Tsugane S, Grp JS. Association of breakfast intake with incident stroke and coronary heart disease The Japan Public Health Center-based study. Stroke. 2016;47(2):477–81.

Johnston JD, Ordovas JM, Scheer FA, Turek FW. Circadian rhythms, metabolism, and chrononutrition in rodents and humans. Adv Nutr. 2016;7(2):399–406.

Jakubowicz D, Wainstein J, Landau Z, Raz I, Ahren B, Chapnik N, et al. Influence of breakfast on clock gene and AMPK mRNA expression and postprandial glycaemia in healthy and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(11):1573–9.

Yoshizaki T, Tada Y, Hida A, Sunami A, Yokoyama Y, Yasuda J, et al. Effects of feeding schedule changes on the circadian phase of the cardiac autonomic nervous system and serum lipid levels. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2013;113(10):2603–11.

Devries JIP, Visser GHA, Mulder EJH, Prechtl HFR. Diurnal and other variations in fetal movement and heart rate patterns at 20–22 weeks. Early Hum Dev. 1987;15(6):333–48.

Okun ML, Schetter CD, Glynn LM. Poor sleep quality is associated with preterm birth. Sleep. 2011;34(11):1493–8.

Zhu JL, Hjollund NH, Olsen J. Shift work, duration of pregnancy, and birth weight: The National Birth Cohort in Denmark. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(1):285–91.

Xu XP, Ding M, Li BL, Christiani DC. Association of rotating shiftwork with preterm births and low birth weight among never smoking women textile workers in China. Occup Environ Med. 1994;51(7):470–4.

Abu Helwa HA, Mitaeb AA, Al-Hamshri S, Sweileh WM. Prevalence of dysmenorrhea and predictors of its pain intensity among Palestinian female university students. Bmc Womens Health. 2018;18(1):18.

Hu Z, Tang L, Chen L, Kaminga AC, Xu HL. Prevalence and risk factors associated with primary dysmenorrhea among Chinese Female University Students: a cross-sectional study. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2020;33(1):15–22.

Fujiwara T, Nakata R. Skipping breakfast is associated with reproductive dysfunction in post-adolescent female college students. Appetite. 2010;55(3):714–7.

Hosono T, Ono M, Daikoku T, Mieda M, Nomura S, Kagami K, et al. Time-restricted feeding regulates circadian rhythm of murine uterine clock. Curr Dev Nutr. 2021;5(5):nzab064.

Fujiwara T, Ono M, Mieda M, Yoshikawa H, Nakata R, Daikoku T, et al. Adolescent Dietary Habit-induced Obstetric and Gynecologic Disease (ADHOGD) as a New Hypothesis-Possible Involvement of Clock System. Nutrients. 2020;12(5):1294.

Zhu S, Cui L, Zhang X, Shu R, VanEvery H, Tucker KL, et al. Habitually skipping breakfast is associated with chronic inflammation: a cross-sectional study. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24(10):2936–43.

Rosset L, Strutz KL. Developmental origins of chronic inflammation: a review of the relationship between birth weight and C-reactive protein. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(7):539–43.

Furukawa S, Miyake T, Miyaoka H, Matsuura B, Hiasa Y. Observational study on unhealthy eating behavior and the effect of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors: the luseogliflozin ehime diabetes study. Diabetes Ther. 2022;13(5):1073–82.

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare:Dietary Guidelines for Pregnant and Nursing Women Starting Before Pregnancy. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/000776926.pdf. Accessed 8 Mar 2023.

Akamatsu R, Maeda Y, Hagihara A, Shirakawa T. Interpretations and attitudes toward healthy eating among Japanese workers. Appetite. 2005;44(1):123–9.

Michikawa T, Nitta H, Nakayama SF, Ono M, Yonemoto J, Tamura K, et al. The Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS): a preliminary report on selected characteristics of approximately 10 000 pregnant women recruited during the first year of the study. J Epidemiol. 2015;25(6):452–8.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their appreciation to the pregnant women in the TMM BirThree Cohort Study and the staff members of the Tohoku Medical Megabank Organization. The list of members is available at https://www.megabank.tohoku.ac.jp/english/a220901/.

Funding

The TMM BirThree Cohort Study was supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED), Japan [grant number, JP17km0105001, JP21tm0124005].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MA designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. KM, IT, TO, AN, FU, FM, MI, TO, HH, NI, MS, JS, NY, and SK contributed to data collection and provided critical feedback. KM and SK provided advice regarding critically essential intellectual content and helped in drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The TMM BirThree Cohort Study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Tohoku University Tohoku Medical Megabank Organization (2013–1-103–1). The methods in this study have been carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided their informed consent at enrollment.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Keiko Murakami is an Editorial Board Member for BMC Public Health. Other authors do not have competing interests as defined by the BMC or any other interests that might influence the results or discussions reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Supplementary Table 1. Nutrient and food group consumption by breakfast intake frequency. Supplementary Table 2. Multivariate linear regression analysis for the association between frequency of breakfast intake during pregnancy and infant birth weight (n=18,307). Supplementary Table 3. Multivariate linear regression analysis of the association between breakfast intake frequency and infant birth weight.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Aizawa, M., Murakami, K., Takahashi, I. et al. Association between frequency of breakfast intake before and during pregnancy and infant birth weight: the Tohoku Medical Megabank Project Birth and Three-Generation Cohort Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 23, 268 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-05603-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-05603-8