Abstract

Background

Approximately one in five women will experience mental health difficulties in the perinatal period. However, for a large group of women, symptoms of adverse perinatal mental health remain undetected and untreated. This is even more so for women of ethnic minority background, who face a variety of barriers which prevents them from accessing appropriate perinatal mental health care.

Aims

To explore minority ethnic women’s experiences of access to and engagement with perinatal mental health care.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 18 women who had been diagnosed with perinatal mental health difficulties and who were supported in the community by a specialist perinatal mental health service in South London, United Kingdom. Women who self-identified as being from a minority ethnic group were purposefully selected. Data were transcribed verbatim, uploaded into NVivo for management and analysis, which was conducted using reflective thematic analysis.

Results

Three distinct overarching themes were identified, each with two or three subthemes: ‘Expectations and Experiences of Womanhood as an Ethnic Minority’ (Shame and Guilt in Motherhood; Women as Caregivers; Perceived to Be Strong and Often Dismissed), ‘Family and Community Influences’ (Blind Faith in the Medical Profession; Family and Community Beliefs about Mental Health and Care; Intergenerational Trauma and Family Dynamics) and ‘Cultural Understanding, Empowerment, and Validation’ (The Importance of Understanding Cultural Differences; The Power of Validation, Reassurance, and Support).

Conclusion

Women of ethnic minority background identified barriers to accessing and engaging with perinatal mental health support on an individual, familial, community and societal level. Perinatal mental health services should be aware ethnic minority women might present with mental health difficulties in different ways and embrace principles of cultural humility and co-production to fully meet these women’s perinatal mental health needs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The perinatal period (through pregnancy and up to one year after birth) is a time of adjustment for all mothers. However, an estimated 10–20% of women will experience adverse mental health in the perinatal period [1, 2]. Unfortunately, a large proportion of women experiencing symptoms are not identified, particularly those from minority ethnic backgrounds [3], with evidence suggesting these women have an increased risk of perinatal mental health difficulties [4,5,6,7] and are more likely to report adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) [8]. In addition, minority ethnic women who report high rates of daily experiences of racism and have been found to have increased risk of perinatal depression, adverse obstetric outcomes such as preterm birth [9] and overall mortality in the perinatal period [10]. This has raised further concerns that Black, Asian, and minority ethnic women may be more likely to fall through gaps in healthcare services [11].

There is a variety of evidence to suggest access to and experiences of healthcare services, including maternity and perinatal mental health services, are far from equitable [12], but limited research has aimed to understand the barriers which prevent women from different minority ethnic backgrounds accessing care [13,14,15,16], or to explore their experiences in the wider context of their lives [17].

The few studies which have investigated barriers to accessing services have identified both system level barriers in primary care [13], psychological therapy services [18,19,20], and maternity services [21, 22]; as well as psycho-social, cultural, and interpersonal barriers [22, 23] and include but are not limited to negative attitudes towards mental illness, inadequate resourced services, language barriers, differences in cultural values and fragmentation of services [13, 21,22,23]. In England, women from Black African, Asian, and White Other ethnic backgrounds access community perinatal mental health services significantly less than White British women, and also report higher percentages of women detained under the Mental Health Act [24]. Research addressing experiences of postnatal depression in South Asian mothers in Great Britain has shown they experienced ‘culture clashes’, leading to feelings of being misunderstood by healthcare professionals, and thus notable difficulties in reporting mental health symptoms during the perinatal period [23]. Other studies have found migrant and ethnic minority women, in general, have a higher risk of anxiety symptoms [7], and may experience barriers related to social deprivation according to the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD; i.e., Income, Employment; Education; Skills and Training; Health and Disability; Crime; Barriers to Housing Services and Living Environment) [25]. Research analysing Black Caribbean women’s perceptions of perinatal mental health care found they were less likely to engage with mental health (and general health) services in the perinatal period if they experienced poor physical healthcare or care deemed lacking in compassion [14]. In the US, use of psychotropic medication has been suggested as another barrier for minority ethnic women, as their preferences with regards to mental health care interventions were found to prioritize faith and social support over the use of medication [26].

The need for culturally sensitive mental health services and acknowledgement of cultural concepts of distress have been widely recognized as a prerequisite for enabling access and engagement of women from minority ethnic groups [27, 28]. To fully understand the barriers these women experience to access and engage with perinatal mental health care, services need to focus more on women’s wider cultural, social and family context [29].

The need for improved access to perinatal mental health services has been widely recognised in the UK in recent years. The National Health Service (NHS) in England has attempted to address issues with access and limited provision for perinatal mental health support by creating a mental health implementation plan [30], in-line with the NHS Long-Term Plan [31]. It includes proposals for increased funding for community-based mental health care, specialist inpatient care for mothers and babies, as well as the recent increase of service provision to two years postnatal, instead of the previous one year. These steps aim to improve access to perinatal mental health services across the UK, potentially reducing the risk of mother and infant morbidity and mortality, and ensuring continuity of care throughout the perinatal period; alongside other guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [32]. This study aims to contribute to this goal by exploring the multi-level barriers Black, Asian, and minority ethnic women experience when accessing mental health services in the perinatal period.

Methods

Setting

This study was conducted within a community perinatal mental health service in South London, covering an area of London where an estimated 17–34% of the population are from minority ethnic backgrounds [33,34,35]. The service covers three boroughs in South London: The London Boroughs of Bromley and Bexley, and The Royal Borough of Greenwich. The number of minority ethnic individuals living in these boroughs are expected to increase [33,34,35], and across the three boroughs, 27% (Bexley), 26% (Bromley), and 61% (Greenwich) of the local population are classified as being deprived, based on the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) [36]. The service offers specialist mental health assessment, care, and treatment for women who are planning a pregnancy, are currently pregnant, or are up to twelve months postpartum. Referrals are accepted from a range of healthcare professionals, including midwives, obstetricians, health visitors, general practitioners (’family doctors’), primary mental health services (commonly referred to as Improving Access to Psychological Therapies [IAPT] services) and other secondary mental health services. The service does not offer crisis or emergency care.

Study Design

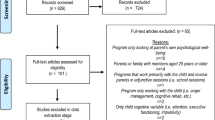

A qualitative research design, using Thematic Analysis, was employed to evaluate minority ethnic women’s experiences of access to and engagement with a community perinatal mental health service in South London. Ethical approval was granted by the Research and Development Office of Oxleas NHS Foundation Trust (approval date: 11/07/2019, Datix reg: 1056). An interview method was utilised in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, with the interview schedule [Additional File 1] having been approved by the Research and Development Office. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants, electronically, in writing before the date of the interview, and participants were made aware of their right to withdraw.

Women who self-identified as being from a minority ethnic group were purposefully selected. Topics covered during the interviews included women’s experiences of accessing and engaging with perinatal mental health care and by extension a range of mental health, community, and maternity services within the NHS. In this study, we use the terms ‘minority ethnic’ or ‘ethnic minority’ (where appropriate) to refer to all the women who participated. When we present data from individual women, we provide their ethnicity, as they self-defined it. We recognise ethnic and cultural backgrounds are more nuanced than the broad groupings often provided, however for the purposes of this study, we utilise this terminology as it is widely used and accepted by the academic and public policy communities in the UK. We acknowledge, however, that this terminology may not resonate with everyone, but hope it demonstrates sensitivity around this complex issue of racial, ethnic, and cultural identities.

Participants and Recruitment

Recruitment took place between May and September 2020. Participants (N = 18) who met the inclusion criteria, were identified and discussed during regular clinical multi-disciplinary team meetings. Inclusion criteria meant women had to 1) self-identify as being from a minority ethnic group (Black, Asian, or any other minority ethnic backgrounds, including White Other); 2) be under the care of the community perinatal mental health service (i.e. pregnant up to one year after the birth of their baby); 3) were over 18yrs of age at the time of recruitment. At a first stage, they were informed about the aims of the study by their designated healthcare professional within the community perinatal mental health service. If they were interested in participating, a member of the study team based within the service (SP), would contact them to explain and discuss further details of the study. Consent was taken via a written consent form prior to interview. It was made clear that women’s decision to participate or not to participate would not affect their clinical care in any way. Of those service users that were approached, four women declined to participate in the study.

Data Collection

An interview schedule (see Additional File 1) was developed (AE, SP) to explore women’s experiences of perinatal mental health services and included topics of access to and engagement with a community perinatal mental health service. The interview schedule was subjected to internal sense-checking, through consultation and supervision with senior staff from the service (SR, SS) and with an academic psychologist with expertise in qualitative methods (SAS). One researcher – who was a trained psychology assistant with experience in working with ethnic minority populations, conducted all the interviews (SP), with consultation and supervision provided throughout the interview process by more senior members of the team (AE, SAS, SR, LMH) [37,38,39]. Interviews were conducted via telephone, and were semi-structured, which allowed for the same topics to be asked of all participants, but with the flexibility in questioning style to follow-up on points made by individuals [40]. Participants were recruited until thematic saturation was established [41], whereby no new themes were being identified through the analysis when new data (interview transcripts) were added. Participants provided written (electronic) informed consent prior to the interviews commencing, and although most demographics were gathered from their clinical notes, ethnicity was recorded as per participants’ self-identification, in response to the question: “Could you tell me the ethnicity with which you identify?”. Interviews lasted between 25–80 min (MTime = 46 min) and were audio-recorded, after which they were transcribed verbatim, and anonymised transcripts were stored in a secure folder, only accessible by members of the research team. Participants were reimbursed for their time through vouchers to the value of £25.

Data Analysis

Interview data were analysed in NVivo [42] using a thematic analysis, which follows methodical process of dataset familiarisation, initial coding, searching for themes, reviewing themes, and finally defining and naming themes [43]. The present analysis reports on an empirical exploration of the impact of ethnicity and cultural differences on accessing and engaging with perinatal mental health care. Data analysis was conducted by one researcher – a non-clinical psychologist (SP), with a confirmatory coding of ~ 20% of transcripts undertaken by another researcher – a clinical perinatal mental health midwife (KDB), ensuring conceptual inter-rater reliability across codes and themes [44]. The cohesion, completeness, and meaningfulness of codes and final themes were checked, discussed, and agreed through regular consultation with the wider study team (AE, SAS, KDB, SS, SR, LMH), throughout data collection and analysis stages. Rigour was maintained in thematic analysis and in our study by reflexively engaging with data and analytical processes throughout the different steps of analysis as detailed above. This ensured any biases brought to the data by analysts were identified and removed iteratively during the inductive analysis.

Results

Half of the women participating in the study self-identified as Black or Black British (n = 8), 4 women as Asian or Asian British, 2 as Arab and 4 as Mixed Other or White Other. Women ranged in age between 19 and 46 years at the time of the interview, with a mean age of 33.4 years. 17 participants were interviewed during the postnatal period, and one during pregnancy. One third of participants were first-time mothers (n = 6). Women’s primary diagnosis -as recorded in their mental health care records – included Bipolar Affective Disorder (n = 2), Anxiety (n = 3), Trauma-Related Diagnoses (including Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder [PTSD] and Emotionally Unstable Personality Disorder) (n = 5), Depression (including post-natal and recurrent) (n = 6) and Psychotic Disorders (n = 2). Full demographic information can be found in Table 1.

Qualitative analysis of the dataset identified three overarching themes and respective further sub-themes, are presented in Table 2, with the most illustrative quotations presented in the text and supplementary quotations in Table 3, at the end of the results section. Each quotation is presented with its corresponding participant identifier and their self-identified ethnic background.

-

1.

Expectations and Experiences of Womanhood as an Ethnic Minority

The first overarching theme related to the expectations of women and being a mother, how this was (or was not) influenced by the experiences of being from a minority ethnic background, and in turn the impact this had on accessing mental healthcare.

-

i.

Shame and Guilt in Motherhood

A vast majority of participants described feelings of shame arising from difficulties with their mental health in the perinatal period, not enjoying the experience of motherhood and a sense of a loss of identity and how this prevented them from seeking help.

“I felt hugely, hugely ashamed of how I was feeling, and that stopped me from accessing services. And I don’t think that’s necessarily the Arabic culture influencing that, I think that’s just the culture of motherhood” (Participant 13, Arabic)

Many participants described emotional difficulties when feeling unable to fulfil certain expectations around motherhood, such as breastfeeding and how these exacerbated feelings of shame and guilt as a mother:

“I used to feel bad I stopped breastfeeding when he was 4 months, I think I felt bad that I did. And then I thought that I was not a good mum” (Participant 14, Black British)

-

ii.

Women as Caregivers

Several participants described the impact of their emotional responsibilities as a caregiver, their role within their family unit and extended family, and the shift in roles from daughter and sister to wife and mother.

“…because I’d just got married, there was a shift from living at home with my sisters and my mum, and also I’m the eldest so my role changed and…they [my family] felt like I was doing a lot for my husband and I’d forgotten about them.” (Participant 12, Black British)

Participants described being expected to carry on with their domestic responsibilities, in addition to childcare, despite it being contraindicated for them to do so and at a time when participants needed to focus on their own recovery.

“On the 6th day after my c-section I had to carry on with all the housework and the midwife was telling me you shouldn’t be doing this because of risk of hernia etc. but I had no other choice” (Participant 4, British Asian)

-

iii.

Perceived to be Strong and Often Dismissed

Several participants described their past experiences of being dismissed by primary healthcare professionals, such as their GP or midwife, when raising concerns about their emotional well-being during routine appointments. They spoke of a reluctance to then ask for help until their mental health difficulties had reached a breaking point, often minimizing the true severity of how they were feeling. This arose within the cultural context of participants feeling as they must be perceived to be strong and may be considered weak for not being able to cope with the difficulties they may be facing.

“But I was worried about how I was going to be perceived …there’s always a thing about being a strong black woman, and sometimes that’s not always the case. We’re not as strong as society expects us to be” (Participant 12, Black British)

For some participants, ideas of being strong was closely interlinked to cultural ideas about women’s strength and spiritual and religious practice.

“…the whole thing of having a psychiatrist and therapy and all that is not…in that culture that is…you have to be a strong person. You pray, try and pray about it. Maybe you’re not religious enough, maybe you’re not spiritual enough, maybe you have to have a stronger faith” (Participant 9, Arab)

Participants from Asian backgrounds frequently described being socialised to minimise conventional overt expressions of physical and emotional pain or suffering. This was, at times, reinforced in services by staff not recognising the cultural differences in how pain is expressed.

“I was in a lot of pain [after an ectopic pregnancy] but…I had to fight to keep my painkillers and they [doctors and nurses on the gynaecology ward] are like oh you seem fine and I’m just like you can’t send me home without painkillers” (Participant 15, British Asian)

-

2.

Family and Community Influences

Many participants discussed how beliefs stemming from their family and community background and community had influenced their views of mental health, experience of services, and the impact this had on their access to care.

-

i.

Blind Faith in the Medical Profession

Participants identifying as Asian often reported a deep-rooted faith in the ability of medical doctors, to whom a higher level of competence was attributed compared to other professionals. This meant their families were more trusting of medical doctors and less likely to contradict their advice.

“There’s kind of a blind faith in medical professionals and that’s definitely cultural. Definitely in the Indian community” (Participant 15, British Asian)

They also reported they were more likely to feel reassured when given health advice by medical doctors and at times would feel disappointed or dismissed when support was given by other, non-medical, professionals.

“I felt more comfortable in myself that the doctor has seen him [the baby] and reviewed him.” (Participant 12, Black British)

“I think earlier on I was expecting more [the doctor] to make contact with me. I was expecting a psychiatrist talking to me at the beginning, but it didn’t happen…what happened was the different one came in, she was a psychologist” (Participant 9, Arab)

-

ii.

Family and Community Beliefs about Mental Health and Care

Many participants described a lack of recognition and understanding of perinatal mental health in their communities. Mental health symptoms were often dismissed by family, and when this was not the case, there was a fear of accessing and engaging openly with services, which increased the risk of an escalation in mental health symptoms. Participants from all minority ethnic backgrounds discussed how mental health was not spoken about and there was a lack of understanding by family and community members around the symptoms and causes for mental health difficulties.

“His mum… had this African mentality in the background, like ‘Oh, you don’t want to go [to the GP]. Okay, you’re fine, don’t worry it’s nothing’” (Participant 12, Black British)

Participants would find these comments blameful, dismissive and hurtful, which aggravated their existing emotional distress.

“They [my family] would just say… ‘there's nothing wrong with you, you have such a beautiful life, you have a child, you have a nice husband, you have a nice house and you're a beautiful girl, so what is wrong with you?’ I used to hear a lot of comments that were very hurtful.” (Participant 14, Black British)

Participants who identified as Black or Mixed ethnicity spoke of family members discouraging disclosures about mental health for fear of the implications, such as social care involvement and removal of their baby at birth.

“…a lot of women don’t go to their GP to tell them they are pregnant so a lot of it does go under the radar, hence a lot of babies are taken at birth because they haven’t communicated during their pregnancy” (Participant 17, Mixed Other)

Fear was also present with regards to medication as a potential line of treatment for their mental health difficulties.

“I was scared of taking the medication because I just didn’t want to be on something that I’m going to rely on… It took me months to actually start those antidepressants. I was taking one or two and then stopping completely and being scared” (Participant 9, Arab)

-

iii.

Inter-generational Trauma and Family Dynamics

Several participants discussed finding out about family mental health problems through their own experiences as well as describing fractured family dynamics. In some cases, participants described not having any contact with family from a very young age, leading to traumatic upbringings and childhood in care.

“I left my family four years ago and I don’t have any contact with them” (Participant 16, White Other)

Others described challenging family dynamics about raising their child as a single parent, leading to inter-generational conflict around amending this and what parental behaviour is deemed acceptable.

“I felt a pressure from my family to try and make things work with her dad. I felt very judged by my family. The same went for after she was born. It amazed me how little her dad had to do for people to think that he deserved more chances or that he was a good dad” (Participant 7, Black British)

-

3.

Cultural Understanding, Empowerment, and Validation

The final theme related to participants’ experiences of clinicians’ cultural understanding, feelings of empowerment and validation and how these acted as facilitators to accessing and engaging with perinatal mental health care.

-

i.

The Importance of Understanding Cultural Differences

Women described they had been met in previous encounters with the healthcare system with a lack of cultural awareness. They had been discriminated against or judged on the basis of their ethnicity and culture and reported negative experiences in relation to their ethnicity, leading to having negative perceptions of the NHS as a system.

“Generally, with NHS services I notice microaggressions all the time…are not overt, but it will be noticing the difference in the way somebody either greets me or I find a lot of receptionists in hospitals will ignore you” (Participant 7, Black British)

Participants reported a wide range of negative experiences, which had led to treatment delays and missed opportunities for care when they disclosed their mental health difficulties in maternity as well as in mental health services. Participants felt their disclosures were dismissed by healthcare professionals, most often at primary care level.

“I was [in a] really, really in a dark place they [the health visitors] told me to eat vitamins, instead of like listening to what I was saying” (Participant 10, White Other)

Others described how professionals were reluctant to refer them to the appropriate mental health service and how the onus to self-refer was completely on them.

“I think the service is amazing once you’re in it, but doctors [General Practitioners] are very reluctant I found, when you’re pregnant. The doctor I saw initially referred me to [a mental health charity], you have to self-refer which doing yourself is not easy. Then you wait for a call, then an interview, it’s all difficult to do when you’re in a bad place.” (Participant 5, British Asian)

To overcome these previous negative experiences, participants described how they felt it was important for their clinicians to be aware of their specific culture and how they related to them as this made them more likely to engage with that clinician.

“Understanding cultural differences is a big thing. In our society in Bangladesh, we are just with partner, we accept a lot of things which are not accepted in British society so if my counsellor doesn’t understand, they [the counsellor] cannot help me” (Participant 4, British Asian)

Others described how cultural awareness and physical resemblance are essential to feel understood by healthcare staff, especially in the context of a perinatal therapeutic relationship.

“With the perinatal, with culture… if you was a black lady with mental health, maybe you wouldn’t want to talk to a white girl…you think white privilege is there and as a black lady you think: does she understand? Does she get me?” (Participant 17, Black British)

-

ii.

The Power of Validation, Reassurance, and Support

Participants described the difference it made when they had support from family and friends during the perinatal period. They also valued the professional support they had received as it made them feel empowered when they didn’t feel worthy of help.

“I didn’t feel at first, worthy? But I think like after I had been and I was reassured that I hadn’t been accepted into the service if I didn’t need it but it’s been a long process I think I’ve constantly thought maybe I was draining the resources” (Participant 10, White Other)

Some women reflected on their own experience and encouraged women to seek and accept help earlier.

“I think the main advice is to get help quite early on…to remove that shame that comes with it all…that was one of the bigger reasons I didn’t fully disclose what was going on.” (Participant 13, Arab)

The insight that women were not alone, but others were going through a similar experience, was reported as being highly important. Women reported to feel reassured when joining the peer support group, which was available to all participants in our sample and where they were able to meet other women they related to.

“So maybe these things are good to have because with peer support, you feel that you’re not alone. Because it can be quite lonely can’t it.” (Participant 10, White Other)

For some women, this sense of camaraderie became increasingly important and powerful as a means to support each other through good times and bad times.

“Like I think four-to-five women who are regulars and we seem to have really opened up to each other and have developed a supportive group and celebrate each other’s wins and commiserate the down times” (Participant 15, British Asian)

Professional reassurance and validation were equally important, especially when they felt their feelings and concerns had previously been dismissed.

“One thing that was really important to me was that feeling when he [the psychiatrist] kept saying I treat so many people in similar situations…no one talks about it. The reassurance…it makes you feel like this is something that people can go through and you’re not the only one” (Participant 5, British Asian)

Discussion

Overall, our findings highlight how minority ethnic women struggle with their own perceptions of what it means to become or to be a ‘good mother’, especially when in receipt of a mental health diagnosis [45, 46]. Under our first theme ‘Expectations and Experiences of Womanhood as an Ethnic Minority’, we demonstrated that women’s perceptions are closely interlinked with their cultural beliefs and influences. Women from Black and Asian backgrounds reported feeling they had to engage with the illusion of being strong for fear of how they may otherwise be perceived. This expectation, by implication, then meant any symptoms of mental ill health acted as a proxy for lesser mental strength or ability to cope [22]. For Black women, this could give further evidence for endorsement of the ‘strong black woman’ stereotype potentially making them more susceptible to stress and depressive symptoms [47, 48].

In addition to barriers linked with cultural beliefs about motherhood specific to women of ethnic minority backgrounds, participants also appeared to experience similar barriers to seeking help as previously reported for women in the perinatal period from non-minoritized backgrounds – particularly stigma and fear of accessing services and treatment [11, 14]. Our analysis showed women expressed anxiety about taking medication in the perinatal period and were more likely to prefer holistic approaches and talking therapies. Although there is a lack of research on this in the perinatal period, it supports the existing evidence that those from minority ethnic backgrounds are less likely to endorse medication in their general mental healthcare preferences [49]. This is pertinent as our research also highlighted difficulties in medication adherence which can potentially exacerbate mental ill-health and may lead to higher rates of involuntary admission to psychiatric hospitals in the perinatal period amongst minority ethnic women [50]. Providing tailored advice and preconception support [51, 52] and addressing medication concerns may be one way to improve these outcomes [50].

As demonstrated under our second theme (Family and Community Influences), strong family and community beliefs surrounding mental health and (mental) healthcare could further compound barriers to accessing mental health support for minority ethnic women who are struggling with their mental health in the perinatal period. This challenges the common view that women seek informal emotional support during the perinatal period from family and friends as a first resource, before they call upon more formal, professional, mental health support [53]. In our sample, many participants felt unable to disclose their mental health difficulties to their families or would minimise the extent of their struggles, out of fear of being dismissed and not being a ‘good enough’ mother or woman [46]. However, these findings do not negate the widely accepted importance of family and other social support as a protective factor in the perinatal period [54], as is evident from the findings under our third and final theme (Cultural Understanding, Empowerment, and Validation). The importance of social support during the recovery from perinatal mental health difficulties [49, 55, 56] was endorsed across all minority ethnic backgrounds within our sample. Previous research has associated family involvement in Black women’s pregnancies with lower depressive symptomatology and may act as a protective factor [57]. Participants in our study also highlighted their mental health would have been far worse without the invaluable practical and emotional support from their partner and/or father of their baby. Another valuable resource of social support highlighted in our findings is that of other women going through a similar experience. Peer support has been found to be hugely beneficial in a perinatal context, not just for women who face mental health difficulties [58, 59] but also for women with additional social vulnerabilities during this time [60].

Furthermore, the findings emphasise the importance of representation of healthcare professionals with whom participants could identify, i.e. healthcare professionals from minority ethnic backgrounds. In absence thereof, our findings highlight the importance of healthcare professionals who show cultural awareness and humility to overcome this lack of representation in the workforce. This reinforces findings from the existing research regarding racial and ethnic disparities in accessing healthcare and treatment [11,12,13,14,15]. Women highlighted the need to provide healthcare staff with cultural awareness so as they can support women to facilitate access to services as well as the overall experience within them. The concept of ‘cultural humility’, introduced by Tervalon and Murray-Garcia in 1998, is critical in this context, as it requires a commitment from healthcare professionals to self-evaluation and self-critique, and to acknowledge there are other models of distress alongside Western models of psychology and psychiatry [28, 61]. To embed cultural humility in mental health services, critical re-thinking of healthcare training and service delivery is needed. Evidence suggests staff in secondary mental health care and midwifery lack training in the needs of minority ethnic women, particularly the healthcare needs of Black women [62]. Robinson et al. (2021) recommends embedding cultural humility in the healthcare workforce using the 5Rs of Cultural Humility (Reflection, Respect, Regard, Relevance and Resilience) to address implicit bias against minority populations and to facilitate organisational culture shifts toward cultural humility in healthcare [63]. In addition, primary care services delivering psychological interventions have highlighted the need for tailoring interventions to minority ethnic populations and providing staff with training to address the current gaps in knowledge of culture and cultural concepts of distress, as well as tackling structural inequalities at service level [19]. To achieve this, co-production has been widely accepted as a successful strategy to reduce mental health inequalities for people from minority ethnic backgrounds [64] and has been adopted by both government, professional bodies and patient groups as the way forward to improve access and engagement in mental healthcare [65].

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

This study provides an in-depth, qualitative understanding of a group of minority ethnic women in South London. The participants interviewed in this study self-identified as ‘being from a minority ethnic background’. This included both women who were born in the UK as well as those who migrated to the UK at a later age. Therefore, our findings do not distinguish between women born in the UK or with migrant status. None of the women had refugee status, and given the specific challenges women with refugee status face, they are not within scope of this study [7]. As such the findings may not be more widely generalisable or representative of the experiences of women in other settings or women who are not ethnic minorities in those other settings. Participants interviewed had high levels of social complexity (such as housing difficulties, lower socio-economic backgrounds, and/or victim of trafficking) which, in itself, can provide additional barriers to service engagement and indeed, participation in research. Further, due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the Government-mandated ‘lockdown’ which was imposed in the UK during the time of recruiting for participants, interviews were conducted remotely via telephone. This meant it was more challenging for some participants to engage with the research, and it may have been more challenging to establish a rapport between researcher and participant due to telephone interview set-up, limited access to internet connections to arrange the interview and credit for mobile phones, which may have affected the depth of discussion. These types of data poverty are essential issues for research teams to address before commencing future research [66]. A strength of the study is the use of qualitative methodology with semi-structured interviews, allowing women to speak freely without being restricted to pre-assigned ideas about their beliefs and feelings about the topics discussed [67]. Given the limited research in this area, future research should be aimed at supporting services to conduct holistic assessments exploring the family network and support, whilst obtaining true insight into women’s individual contexts.

Conclusion

Our study provides new insight into the experiences of minority ethnic women when accessing and engaging with mental health services in a perinatal context. Women identified barriers to accessing support during this time on an individual, familial, social network, and societal level. The tension between cultural beliefs and expectations of woman – and motherhood – on one hand and their day-to-day lived experience of mental health difficulties, on the other, compounded their existing psychological distress and undermined their self-worth as a mother.

Furthermore, the understanding of perinatal mental health pathways has been cited as a key way of helping women receive specialist advice, reach the appropriate services at the right time, and respond effectively to any difficulties they may be experiencing[59]. These needs should be carefully considered for minority ethnic women who may present with mental health difficulties in different ways. This cannot be achieved without increased training for healthcare professionals in cultural humility and by adoption of co-production in mental healthcare, in order to address systemic health inequalities and to tailor and improve mental health care to fully meet the needs of the communities they serve.

Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement

This programme of work has been presented to, and received input from the National Institute for Health Research Applied Research Collaboration [NIHR ARC] South London Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement [PPIE] meeting for Maternity and Perinatal Mental Health Research (July 2020; June 2021), which has a focus on co-morbidities, inequalities, and maternal ethnicity. Throughout the course of planning and undertaking this work we have received feedback from both lay and expert stakeholders, including members of the public, those with lived experience, health and social care professionals, researchers, and policy makers.

Availability of Data and Materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during this study are not publicly available due to the sensitive nature of the interviews. Summary data may be shared from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, when compliant with ethical regulation of this study.

Abbreviations

- ACE:

-

Adverse Childhood Experiences

- ARC:

-

Applied Research Collaboration

- EUPD:

-

Emotionally Unstable Personality Disorder

- GP:

-

General Practitioner

- IAPT:

-

Improving Access to Psychological Therapies

- NHS:

-

National Health Service

- NICE:

-

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- NIHR:

-

National Institute for Health and Care Research

- PPIE:

-

Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement

- PTSD:

-

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- US:

-

United States (of America)

References

Howard LM, Khalifeh H. Perinatal mental health: a review of progress and challenges. World Psychiatry. 2020;19:313–27.

Ayers S, Shakespeare J. Should perinatal mental health be everyone’s business? Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2015;16:323–5.

Prady S, Pickett K, Croudace T, Fairley L, Bloor K, Gilbody S, et al. Psychological distress during pregnancy in a multi-ethnic community: findings from the born in Bradford cohort study. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e60693.

Womersley K, Ripullone K, Hirst J. Tackling inequality in maternal health: Beyond the postpartum. Futur Healthc J. 2021;8:31–5.

Prady S, Pickett K, Gilbody S, Petherick E, Mason D, Sheldon T, et al. Variation and ethnic inequalities in treatment of common mental disorders before, during and after pregnancy: combined analysis of routine and research data in the Born in Bradford cohort. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:99.

Anderson F, Hatch S, Comacchio C, Howard L. Prevalence and risk of mental disorders in the perinatal period among migrant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2017;20:449–62.

Anderson F, Hatch S, Ryan E, Trevillion K, Howard L. Impact of Insecure Immigration Status and Ethnicity on Antenatal Mental Health Among Migrant Women. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(5):18m12563.

Kim H, Kuendig J, Prasad K, Sexter A. Exposure to Racism and Other Adverse Childhood Experiences Among Perinatal Women with Moderate to Severe Mental Illness. Community Ment Health J. 2020;56:867–74.

Slaughter-Acey J, Sealy-Jefferson S, Helmkamp L, Caldwell C, Osypuk T, Platt R, et al. Racism in the form of micro aggressions and the risk of preterm birth among black women. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26:7-13.e1.

Knight M, Bunch K, Cairns A, Cantwell R, Cox P, Kenyon S, et al. Saving lives, improving mothers’ care. Rapid report: learning from SARS-CoV-2-related and associated maternal deaths in the UK. March–May, 2020. University of Oxford; 2020.

Edge D. Falling through the net - black and minority ethnic women and perinatal mental healthcare: health professionals’ views. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:17–25.

Rayment-Jones H, Harris J, Harden A, Khan Z, Sandall J. How do women with social risk factors experience United Kingdom maternity care? A realist synthesis Birth. 2019;46:461.

Sambrook Smith M, Lawrence V, Sadler E, Easter A. Barriers to accessing mental health services for women with perinatal mental illness: systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies in the UK. BMJ Open. 2019;9(1):e024803.

Edge D. “It’s leaflet, leaflet, leaflet then, ‘see you later’”: black Caribbean women’s perceptions of perinatal mental health care. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61:256–62.

Webb R, Uddin N, Ford E, Easter A, Shakespeare J, Roberts N, et al. Barriers and facilitators to implementing perinatal mental health care in health and social care settings: a systematic review. The lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:521–34.

Pierce M, Hope H, Ford T, Hatch S, Hotopf M, John A, et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. The lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:883–92.

Edge D. “We don’t see Black women here”: an exploration of the absence of Black Caribbean women from clinical and epidemiological data on perinatal depression in the UK. Midwifery. 2008;24:379–89.

Viveiros C, Darling E. Perceptions of barriers to accessing perinatal mental health care in midwifery: A scoping review. Midwifery. 2019;70:106–18.

Naz S, Gregory R, Bahu M. Addressing issues of race, ethnicity and culture in CBT to support therapists and service managers to deliver culturally competent therapy and reduce inequalities in mental health provision for BAME service users. Cogn Behav Ther. 2019;12.

Millett L, Lever Taylor B, Howard L, Bick D, Stanley N, Johnson S. Experiences of Improving Access to Psychological Therapy Services for Perinatal Mental Health Difficulties: a Qualitative Study of Women’s and Therapists’ Views. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2018;46:421–36.

Bayrampour H, Hapsari A, Pavlovic J. Barriers to addressing perinatal mental health issues in midwifery settings. Midwifery. 2018;59:47–58.

Watson H, Harrop D, Walton E, Young A, Soltani H. A systematic review of ethnic minority women’s experiences of perinatal mental health conditions and services in Europe. PLoS One. 2019;14(1):e0210587.

Wittkowski A, Zumla A, Glendenning S, Fox JRE. The experience of postnatal depression in South Asian mothers living in Great Britain: a qualitative study. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2012;29:480–92.

Jankovic J, Parsons J, Jovanović N, Berrisford G, Copello A, Fazil Q, et al. Differences in access and utilisation of mental health services in the perinatal period for women from ethnic minorities-a population-based study. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):245.

Traviss G, West R, House A. Maternal mental health and its association with infant growth at 6 months in ethnic groups: results from the Born-in-Bradford birth cohort study. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e30707.

Nadeem E, Lange J, Miranda J. Mental health care preferences among low-income and minority women. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2008;11:93–102.

Saherwala Z, Bashir S, Gainer D. Providing Culturally Competent Mental Health Care for Muslim Women. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2021;18:33.

Kohrt BA, Rasmussen A, Kaiser BN, Haroz EE, Maharjan SM, Mutamba BB, et al. Cultural concepts of distress and psychiatric disorders: literature review and research recommendations for global mental health epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:365–406.

Lever Taylor B, Billings J, Morant N, Bick D, Johnson S. Experiences of how services supporting women with perinatal mental health difficulties work with their families: a qualitative study in England. BMJ Open. 2019;9(7):e030208.

Farmer P, Dyer J. The five year forward view for mental health. A report from the independent Mental Health Taskforce to the NHS in England. NHS England, London; 2016.

NHS England. NHS Long Term Plan. NHS England, London; 2019.

Howard LM, Megnin-Viggars O, Symington I, Pilling S. Antenatal and postnatal mental health: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ. 2014;349.

Group BCC. London Borough of Bexley Joint Strategic Needs Assessment. London; 2016.

Bromley Clinical Commissioning Group. Bromley Joint Strategic Needs Assessment 2017 – Demography. https://www.bromley.gov.uk/downloads/file/3367/jsna_demography. Accessed 27 Apr 2022.

Divajeda D, Owusu-Agyemang K. Wood A. Greenwich Joint Strategic Needs Assessment: Greenwich Population Profile; 2016. p. 2016.

NHS England. Equalities Analysis NHS South East London – Scoping Report September 2016. https://www.ourhealthiersel.nhs.uk/Downloads/OHSEL%20Equalities%20Analysis%20Scoping%20Report.pdf. Accessed 27 Apr 2022.

Edwards R. Connecting method and epistemology: A white women interviewing black women. Womens Stud Int Forum. 1990;13:477–90.

Edwards R. White Woman researcher-Black women subjects. Fem Psychol. 1996;6:169–75.

Fernald D, Duclos C. Enhance your team-based qualitative research. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:360–4.

McIntosh M, Morse J. Situating and Constructing Diversity in Semi-Structured Interviews. Glob Qual Nurs Res. 2015;2:2333393615597674.

Francis J, Johnston M, Robertson C, Glidewell L, Entwistle V, Eccles M, et al. What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol Health. 2010;25:1229–45.

Zamawe F. The Implication of Using NVivo Software in Qualitative Data Analysis: Evidence-Based Reflections. Malawi Med J. 2015;27:13–5.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101.

Armstrong D, Gosling A, Weinman J, Marteau T. The Place of Inter-Rater Reliability in Qualitative Research: An Empirical Study: Sociology. 1997;31:597–606.

Staneva AA, Bogossian F, Morawska A, Wittkowsk A. “I just feel like I am broken. I am the worst pregnant woman ever”: A qualitative exploration of the “at odds” experience of women’s antenatal distress. Health Care Women Int. 2017;38:658–86.

Silverio SA, Wilkinson C, Fallon V, Bramante A, Staneva A. When a mother’s love is not enough: A cross-cultural critical review of anxiety, attachment, maternal ambivalence, abandonment, and infanticide. In: Mayer C-H, Vanderheiden E, editors. International handbook of love: Transcultural and transdisciplinary perspectives. Cha, Switzerland: Springer; 2021. p. 291–315.

West LM, Donovan RA, Daniel AR. The Price of Strength: Black College Women’s Perspectives on the Strong Black Woman Stereotype. Women Ther. 2016;39:390–412.

Donovan RA, West LM. Stress and Mental Health: Moderating Role of the Strong Black Woman Stereotype. J Black Psychol. 2014;41:384–96.

Burgess A. Fathers’ Roles in Perinatal Mental Health Causes, Interactions, and Effects. New Dig. 2011;53:21–5.

Jankovic J, Parsons J, Jovanovic N, Berrisford G, Copello A, Fazil Q, et al. Differences in access and utilisation of mental health services in the perinatal period for women from ethnic minorities-a population-based study. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):245.

Lever Taylor B, Kandiah A, Johnson S, Howard L, Morant N. A qualitative investigation of models of community mental health care for women with perinatal mental health problems. J Ment Heal. 2020;30(5):594–600.

Tuomainen H, Cross-Bardell L, Bhoday M, Qureshi N, Kai J. Opportunities and challenges for enhancing preconception health in primary care: qualitative study with women from ethnically diverse communities. BMJ open. 2013;3(7):e002977.

Hadfield H, Wittkowski A. Women’s Experiences of Seeking and Receiving Psychological and Psychosocial Interventions for Postpartum Depression: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis of the Qualitative Literature. J Midwifery Women’s Heal. 2017;62:723–36.

Milgrom J, Hirshler Y, Reece J, Holt C, Gemmill AW. Social Support—A Protective Factor for Depressed Perinatal Women? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(8):1426.

Atkinson L, Silverio SA, Bick DE, Fallon V. Relationships between paternal attitudes, paternal involvement, and infant-feeding outcomes: Mixed-methods findings from a global on-line survey of English-speaking fathers. Matern Child Nutr. 2021;17:1–15.

Baldwin S, Griffiths P. Do specialist community public health nurses assess risk factors for depression, suicide, and self-harm among South Asian mothers living in London? Public Health Nurs. 2009;26:277–89.

Hawkins M, Misra S, Zhang L, Price M, Dailey R, Giurgescu C. Family involvement in pregnancy and psychological health among pregnant Black women. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2021;35:42–8.

Fang Q, Lin L, Chen Q, Yuan Y, Wang S, Zhang Y, et al. Effect of peer support intervention on perinatal depression: A meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2021;74:78–87.

McLeish J, Redshaw M. Mothers’ accounts of the impact on emotional wellbeing of organised peer support in pregnancy and early parenthood: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:28.

Olding M, Cook A, Austin T, Boyd J. “They went down that road, and they get it”: A qualitative study of peer support worker roles within perinatal substance use programs. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2022;132:108578.

Tervalon M, Murray-García J. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1998;9:117–25.

Phillips L. Assessing the knowledge of perinatal mental illness among student midwives. Nurse Educ Pract. 2015;15:463–9.

Robinson D, Masters C, Ansari A. The 5 Rs of Cultural Humility: A Conceptual Model for Health Care Leaders. Am J Med. 2021;134:161–3.

Lwembe S, Green SA, Chigwende J, Ojwang T, Dennis R. Co-production as an approach to developing stakeholder partnerships to reduce mental health inequalities: an evaluation of a pilot service. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2017;18:14–23.

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Working well together: evidence and tools to enable co-production in mental health commissioning. London: National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health; 2019.

Fernandez Turienzo C, Newburn M, Agyepong A, Buabeng R, Dignam A, Abe C, et al. Addressing inequities in maternal health among women living in communities of social disadvantage and ethnic diversity. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):176.

Galletta A. Mastering the Semi-Structured Interview and Beyond: From Research Design to Analysis and Publication on JSTOR. New York: NYU Press; 2013.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to all the women who were able to share their experiences with us, alongside all the clinicians at the NHS Trust with whom we worked.

Funding

Sabrina Pilav, Kaat De Backer, Dr. Abigail Easter, Prof. Louise M. Howard, and Sergio A. Silverio (King’s College London) are currently supported by the National Institute for Health Research Applied Research Collaboration South London [NIHR ARC South London] at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. Kaat De Backer (King’s College London) was supported by NIHR East of England Applied Research Collaboration [NIHR ARC East of England] at Cambridgeshire and Peterborough NHS Foundation Trust. The views expressed are those of the author[s] and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. Sabrina Pilav and the wider service evaluation were funded through the NHSE/ the NHS perinatal service we worked with.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: [SP; AE; SS; SR; LMH]; Methodology: [AE; SP; LMH; SAS]; Software: [SP; AE; KDB; SAS]; Validation: [AE; SAS; SS; SR; LMH]; Formal Analysis: [SP; KDB]; Resources: [AE; SS; SR; LMH]; Data Curation: [SP; AE; KDB; SAS]; Writing – original draft: [SP; KDB]; Writing – review and editing: [AE; SAS; SS; SR; LMH]; Supervision: [AE; SR; SAS; LMH]; Project Administration: [SP]. All author's read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate

Ethical approvals were sought and granted by the Research and Development Office of Oxleas NHS Foundation Trust [approval date: 11/07/2019, Datix reg: 1056]. An interview method was utilised in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, with the interview schedule [Additional File 1] having been approved by the Research and Development Office. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants, electronically, in writing before the date of the interview, and participants were made aware of their right to withdraw.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships which could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Interview Schedule

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Pilav, S., De Backer, K., Easter, A. et al. A qualitative study of minority ethnic women’s experiences of access to and engagement with perinatal mental health care. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 22, 421 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-04698-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-04698-9