Abstract

Background

Birth preparedness and complication readiness are broadly endorsed by governments and international agencies to reduce maternal and neonatal health threats in low income countries. Maternal education is broadly positioned to positively affect the mother’s and her children’s health and nutrition in low income countries. Thus, this systematic review and meta-analysis aims to estimate the effect of maternal education on birth preparedness and complication readiness.

Methods

This review was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis. We conducted an electronic based search using data bases of PubMed /MEDLINE, Science direct and google scholar. STATA™ Version 14.1 was used to analyze the data, and forest plots were used to present the findings. I2 test statistics and Egger’s test were used to assess heterogeneity and publication bias. Pooled prevalence and pooled odd ratios with 95% confidence intervals were computed. Finally, Duval and Tweedie’s nonparametric trim and fill analysis using random-effects meta-analysis was conducted to account for publication bias.

Results

In this meta-analysis, 20 studies involving 13,744 pregnant women meeting the inclusion criteria were included, of which 15 studies reported effects of maternal education on birth preparedness and complication readiness. Overall estimated level of birth preparedness and complication readiness was 25.2% (95% CI 20.0, 30.6%). This meta-analysis found that maternal education and level of birth preparedness and complication readiness were positively associated. Pregnant mothers whose level of education was primary and above were more likely to prepare for birth and obstetric emergencies (OR = 2.4, 95% CI: 1.9, 3.1) than non-educated mothers.

Conclusion

In Ethiopia, the proportion of women prepared for birth and related complications remained low. Maternal education has a positive effect on the level of birth preparedness and complication readiness. Therefore, it is imperative to launch programs at national and regional levels to uplift women’s educational status to enhance the likelihood of maternal health services utilization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In 2015, around 830 women deceased everyday due to pregnancy and childbirth-related complications worldwide. Among these, 550 happened in sub-Saharan Africa and 180 deaths in Southern Asia, compared to 5 in high income countries [1, 2]. Most maternal deaths are attributed to lack of quality maternal care in addition to lack of access to skilled routine emergency care [3, 4].

Most maternal deaths are easily avertable, as health-care solutions to prevent and manage pregnancy related complications are well known. Early antenatal care (ANC), skilled care during childbirth, and care and support in the weeks immediately after birth are the most effective strategies [5]. There is extensive evidence related to delays in deciding, reaching and receiving care and their consequences [6,7,8,9]. Although Birth Preparedness or Complication readiness (BPCR) is a broad and integrative strategy, lack of evidence exists in relation to its comprehensive and holistic application. However, components of the BPCR matrix have been employed and assessed in many settings [10,11,12,13].

Basic components of birth plan packages include: identification of danger signs, plan for a skilled birth attendant, identifying place of birth, blood donors, and saving money for transport or other costs, should such needs arise [5, 14]. Complications, such as hemorrhage, are common problem and potentially fatal if timely treatment is not obtained [7, 15]. This context makes the BPCR package a key strategy in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), including Ethiopia, where obstetric services are generally inadequate and/or underutilized. The BPCR initiative was initiated across SSA in the early 2000s for the purpose of increasing health facility births in combination with the introduction of focused antenatal care (FANC) [16, 17].

Ethiopia has a persistently high maternal mortality ratio (MMR), despite progress towards the millennium development goals [18, 19]. Accordingly, in the last 15 years, MMR reduced from 871 to 412 per 100,000 live-births [20]. However, the proportion of BPCR in Ethiopia varied across the regions. Various cross-sectional studies showed that the level of BPCR ranged from as low as 16.5% in Robe District to as high as 56.3% in the Federal Police Referral Hospital, Addis Ababa [17, 21].

Research shows that there is a strong linkage between maternal education and utilization of reproductive health services [22, 23]. When women’s education increases, their own and their children’s health and nutrition are positively impacted [22]. Although literature has shown low maternal education to be a common variable for under or poor practice of BPCR, there is no research to confirm whether it is a consistent finding and the overall effect size has not been established [15, 24, 25]. Hence, this study aims to establish pooled effects of maternal education on BPCR of pregnant women in Ethiopia by quantifying the association between increased maternal education and BPCR practice. Estimating pooled effects of maternal education on BPCR among pregnant mothers is important in addressing birth-related complications as well as for implementing focused ANC. In addition, the purpose of this study was to estimate pooled prevalence of BPCR practice among Ethiopian pregnant women. While it has been estimated and studied in previous research in Ethiopian context [26], limited number of articles were included in the former article [26] and did not address factors affecting for low utilization of BPCR. However, there was a narrative synthesis of qualitative information on implementation of BPCR [27]. But in the motioned study [27] review the existing article using narrative review, which was prone selection and evaluation bias and even not reproducible. Therefore, our study has designed to address these identified gaps. In addition, our study has used more robust design (systematic review and meta-analysis). Moreover, with the growing demand for evidence based interventions of safe motherhood programs, this systematic review and meta-analysis will add to the evidence base of effective promotion and implementation of BPCR.

Methods

This systematic review has been prepared according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guideline (Supplementary file 1). We searched the databases: PubMed/MEDLINE, and Science Direct. Google scholar and snowball approach were also employed. The following keywords were used: “level of birth preparedness and complication readiness” [MeSH Terms] OR “birth preparedness and complication readiness” [All fields] AND “birth preparedness” [All fields] OR “complication readiness” [All fields] and “prevalence” [Subheading] OR “pregnant women” [All fields] AND “Ethiopia” [MeSH Terms] OR “Ethiopia” [All fields], “maternal education”.

Study selection

Predefined inclusion criteria

-

Study setting: Ethiopia.

-

Study participants: Pregnant women.

-

Publication condition: All published and unpublished articles.

-

Language: English language

-

Types of studies: Observational study designs.

-

Publication date: Until December 31, 2018

Exclusion criteria

-

Unable to access full-texts after two email contacts of the principal investigator.

Outcome of interests

Primary outcome was the pooled prevalence of BPCR among Ethiopian pregnant women. Secondary outcome was the effect of maternal education on the level of BPCR among Ethiopian pregnant mothers. Effect size was estimated in the form of log odds ratios.

Data collection and quality score

A standardized data extraction format was prepared in the form of Microsoft Excel. This included primary author name, publication year, region, study design, sample size, number of subjects with outcome, prevalence, and study areas. Three reviewers (DBK, AA and GDK) extracted the data independently. Any differences among reviewers were negotiated with review team members until agreement was reached. Two authors (GDK and MAA), using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) quality assessment tool adapted for cross-sectional studies to assess, independently evaluated the quality of each original study [28]. Any disagreements were resolved by taking the mean score. Finally, studies with a scale of ≥5 out of 10 were considered as achieving high quality.

Heterogeneity and publication bias

Statistical heterogeneity was evaluated using I2 test and p-values of Cochrane-Q statistics. Heterogeneity was classified as low, moderate, or high when I2 test statistics results were 25, 50, and 75% [29]. Dispersion of individual results in the forest plots was also used to evaluate heterogeneity visually. To check publication bias, both objective and subjective (funnel plot) methods were used. Mainly, objective methods such as Eggers’ and Beggs’ tests (p-value < 0.05) were used to assess publication bias [30, 31]. The result of Eggers’ test revealed statistically significant publication bias (p-value < 0.001). Finally, Duval and Tweedie’s nonparametric trim and fill analysis was performed to account for this publication bias.

Data synthesis

Relevant data from each study were imported into Stata™ Version 14 for further analysis, and results were presented in Tables and forest plot. A random effects meta-analysis model was employed to estimate the Der Simonian and Laird’s pooled effect because of high levels of heterogeneity. Meta-regression was performed to relate the effects of study characteristics, such as sample size, publication year, and region on pooled estimates of BPCR and identify possible sources of heterogeneity. Sensitivity analysis using a random effects model was performed to assess the influence of a single study on the overall meta-analysis estimate.

Results

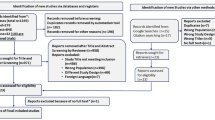

A total of 935 studies were collected from different databases (Fig. 1). All duplicate articles (n = 421) were removed. From the remaining 514 articles, 491 articles were excluded because their titles and abstracts were not in line with our inclusion criteria. Lastly, a total of 23 full text studies were downloaded and assessed for eligibility criteria. Among accessed full text articles, three were excluded because in two papers outcome of interests was not reported [32, 33] and one study was not primary study [26]. Final meta-analysis used the remaining 20 studies. The majority (95%) of the studies employed cross-sectional study designs with a total population of 13,744 pregnant women. Prevalence of BPCR ranged from 16.5% in Robe District, Oromia Region [17] to 56.3% in Addis Ababa [21]. Based on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for cross-sectional studies quality assessment tool, the quality score ranged from 4 to 9 (Table 1).

Pooled level of birth preparedness and complication readiness

Overall random effects estimate of the level of BPCR across Ethiopian studies was 34.0% (95% CI: 29.3, 38.8%) (Fig. 2). This observed effect size varies somewhat from study to study. Test statistics results showed high heterogeneity (=97.5%, p < 0.001) and Eggers’ test (p-value < 0.001) showed significant publication bias. After we applied trim and fill meta-analysis, the overall random effect estimates of BP/CR across studies reduced to 25.2% (95% CI: 20.0, 30.6%) (Table 2). Higher level of BP/CR was observed in Dire Dawa, which was 54.7% (95% CI: 50.0, 62.6%) (Table 3).

Effects of maternal education on BP/CR

Fifteen studies assessed the effect of maternal education on the prevalence of BPCR. Significant heterogeneity was found across studies (I2 = 84.3%, p < 0.001) which enabled us to use a random effects model. Using this method, our meta-analysis found that maternal education has a significant effect on the BPCR utilization. Pooled odds ratio of BPCR among pregnant women who had primary or greater level of education was 2.44 times more likely as compared to their illiterate counterparts (OR = 2.4, 95% CI: 1.9, 3.1) (Fig. 3).

We explored possible sources of heterogeneity using different statistical techniques. Univariate meta-regression was performed using publication year, sample size, and regions as covariates. However, none of these variables were statistically significant for explaining heterogeneity (Table 4). The presence of publication bias was also assessed using funnel plot and Eggers’ and Beggs’ statistical tests at 5% significant level. The funnel plot shows a symmetrical distribution (Supplementary file 2). However, the Beggs’ and Egger tests showed no significant publication bias with p-values of 0.6 and 0.5 respectively. Therefore, publication bias is not a problem.

Sensitivity analysis

To detect the influence of one study on the overall meta-analysis estimate, sensitivity analysis using a random effects model did not show strong evidence for the influence of a single study on the overall result (Supplementary file 3).

Discussion

Overall pooled estimate of the prevalence of BPCR across Ethiopian studies was 34.0% (95% CI: 29.3, 38.8%); this finding, however, has been affected by publication biases. To account for this, the trim and fill meta-analysis found that only 25.2% (95% CI: 20.0, 30.6%) were well prepared for birth and related complications by practicing elements of BPCR. Our finding is higher than studies done in the rural Gambia (14%) and Kenya (6.9%) [48, 49]. Discrepancies may be due to Ethiopia’s flexible initiatives over time to bring more attention to the issue. On the contrary, however, our finding is much lower than in the rural parts of Uganda (35%), Nigeria (61%), Central Tanzania (58.20%), West Bengal, India (57%), Indore City, India (47.8%), and Thailand (78.6%) [13, 50,51,52,53,54].

These differences could be due to socio-cultural issues, like the use of traditional birth attendants, women’s educational and economic status, and differences in the quality of antenatal care services. Participation of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), which may introduce safe motherhood and female rights, may differ in different parts of these countries. Moreover, this finding is slightly lower than a previous meta-analysis from Ethiopia using 13 studies (32%) [26]. This discrepancy could be due to less studies (13) in the previous review, whereas we included 20 studies. Smaller number of studies may overestimate results. This finding has important implications and should alarm relevant stakeholders to invest in health promotion with regard to BPCR, at all stages of women’ reproductive lives, with support from health care workers. In addition, quality and methods of antenatal care education, including evaluation of how women are benefitted from such education, have to be re-assessed.

Maternal education has a significant effect on the prevalence of BPCR (OR = 2.4, 95% CI: 1.9, 3.1). This is in agreement with studies conducted in southern Tanzania and India [52, 55, 56]. Educated women have better access to information and an enhanced position of women in the household may lead to enhanced decision-making power with regard to health-related issues. Women with formal education were found more likely to have knowledge on the key components of birth preparedness and complication readiness as compared to uneducated women. In a qualitative study on BPCR in rural Tanzania educated women were more likely to accept BPCR-elements, to be better informed, to make healthier choices and more likely to develop and implement a birth plan, and to be more socially or financially authorized to make the required decisions in case of obstetric emergencies [23].

Ethiopia has made significant progress towards reducing maternal and neonatal deaths through BPCR, but progression is relatively unsatisfactory. Therefore, it is recommended to launch programs at national and regional level to raise women’s educational status, which would enhance utilization of maternal health services. Another expected effect of maternal education is to increase BPCR knowledge, which may change individual attitudes. Literate women know about danger signs or possibility of obstetric complications as well as about the importance of using skilled birth attendants. Health workers or volunteers should include literate women in meetings of female clusters to share their experiences with uneducated women. Symbolic cards, video-films, and case stories can be used during prenatal meetings to promote understanding of BPCR messages. Knowledge on birth preparedness and key danger signs in pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum are found to be a significant influencer on utilization of skilled attendants [7, 57, 58].

Limitations of the study

Tremendous efforts have been made to include all papers from Ethiopia, but only articles published in English were considered. Moreover, 95% of the studies in this meta-analysis employed a cross-sectional study design. Cause-effect relationships, therefore, cannot be shown in this review. Finally, we were unable to get studies from Benishangul Gumuz, Ethio-Somali, Afar, and Gambella regions and this affects generalizability.

Conclusion

In Ethiopia, the proportion of women who are birth prepared and ready for complications remained low. Pregnant women with primary and higher levels of education were better prepared for birth and related complications than uneducated counterparts. Therefore, it is imperative to launch sustainable programs at national and regional levels which uplift women’s educational status to enhance utilization of maternal health services.

Availability of data and materials

Data will be available from the corresponding author upon resendable request.

Abbreviations

- BPCR:

-

Birth preparedness and complication readiness

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- FANC:

-

Focused antenatal care

- MMR:

-

Maternal mortality ratio

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- SE:

-

Standard error

- SNNPR:

-

South Nation and Nationalities People of the Region

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Alkema L, Chou D, Hogan D, Zhang S, Moller A-B, Gemmill A, Fat DM, Boerma T, Temmerman M, Mathers C. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in maternal mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN maternal mortality estimation inter-agency group. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):462–74.

Maternal mortality fact sheets. http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality. Accessed 4 Dec 2018.

WHO, UNFPA, UNICEF a, Reduction of maternal mortality: a joint WHO. UNFPA/UNICEF/World Bank statement WHO 1999, 20:11–12.

Starrs AM. Safe motherhood initiative: 20 years and counting. Lancet. 2006;368(9542):1130–2.

Lawrence AL, Jimmy JA, Okoye V, Abdulraheem A, Igbans RO, Uzere M. Birth preparedness and complication readiness among pregnant women in Okpatu community, Enugu state, Nigeria. Int J Innov Appl Stud. 2015;11(3):644.

Mbalinda SN, Nakimuli A, Kakaire O, Osinde MO, Kakande N, Kaye DK. Does knowledge of danger signs of pregnancy predict birth preparedness? A critique of the evidence from women admitted with pregnancy complications. Health Res Policy Syst. 2014;12(1):60.

August F, Pembe AB, Kayombo E, Mbekenga C, Axemo P, Darj E. Birth preparedness and complication readiness–a qualitative study among community members in rural Tanzania. Glob Health Action. 2015;8(1):26922.

Hailu M, Gebremariam A, Alemseged F, Deribe K. Birth preparedness and complication readiness among pregnant women in southern Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e21432.

Gebre M, Gebremariam A, Abebe TA. Birth preparedness and complication readiness among pregnant women in Duguna Fango District, Wolayta zone, Ethiopia. PloS One. 2015;10(9):e0137570.

Soubeiga D, Sia D, Gauvin L. Increasing institutional deliveries among antenatal clients: effect of birth preparedness counselling. Health Policy Plan. 2013;29(8):1061–70.

Soubeiga D, Sia D. Birth preparedness in antenatal care: effects of health center characteristics. Revue d’epidemiologie et de Sante Publique. 2013;61(4):299–310.

Karkee R, Lee AH, Binns CW. Birth preparedness and skilled attendance at birth in Nepal: implications for achieving millennium development goal 5. Midwifery. 2013;29(10):1206–10.

Onayade A, Akanbi O, Okunola H, Oyeniyi C, Togun O, Sule S. Birth preparedness and emergency readiness plans of antenatal clinic attendees in Ile-ife, Nigeria. Nigerian Postgraduate Med J. 2010;17(1):30–9.

Del Barco R. Monitoring birth preparedness and complication readiness. Tools Indicators Matern Newborn Health. 2004.

Udofia EA, Obed SA, Calys-Tagoe BN, Nimo KP. Birth and emergency planning: a cross sectional survey of postnatal women at Korle Bu teaching hospital, Accra, Ghana. Afr J Reprod Health. 2013;17(1):27–40.

Ekabua JE, Ekabua KJ, Odusolu P, Agan TU, Iklaki CU, Etokidem AJ. Awareness of birth preparedness and complication readiness in southeastern Nigeria. ISRN Obstetr Gynecol. 2011;2011.

Kaso M, Addisse M. Birth preparedness and complication readiness in robe Woreda, Arsi zone, Oromia region, Central Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Reprod Health. 2014;11(1):55.

Gaym A. Maternal mortality studies in Ethiopia--magnitude, causes and trends. Ethiop Med J. 2009;47(2):95–108.

Tessema GA, Laurence CO, Melaku YA, Misganaw A, Woldie SA, Hiruye A, Amare AT, Lakew Y, Zeleke BM, Deribew A. Trends and causes of maternal mortality in Ethiopia during 1990–2013: findings from the global burden of diseases study 2013. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):160.

Central Statistical Agency (CSA): Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey avalaible from https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-fr328-dhs-final-reports.cfm. In. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 2016. Accessed 6 Dec 2018.

Seble T. Awareness on birth preparedness and complication Readines s among antenatal care clients in Federal Police Referral Hospital Addi s Ababa, Ethiopia. Am J Health Res. 2015;3:362–7.

Kakaire O, Kaye DK, Osinde MO. Male involvement in birth preparedness and complication readiness for emergency obstetric referrals in rural Uganda. Reprod Health. 2011;8(1):12.

Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS). Uganda Demographic and Health Survey. In: Uganda Bureau of Statistics and ORC Macro; 2007.

Tafa A, Hailu D, Ebrahim J, Gebrie M, Wakgari N. Birth preparedness and complication readiness plan among antenatal care attendants in Kofale District, South East Ethiopia: A Cross Sectional Survey; 2018.

Zepre K, Kaba M. Birth preparedness and complication readiness among rural women of reproductive age in abeshige district, guraghe zone, snnPr, Ethiopia. Int J Women's Health. 2017;9:11.

Berhe AK, Muche AA, Fekadu GA, Kassa GM. Birth preparedness and complication readiness among pregnant women in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Health. 2018;15(1):182.

Miltenburg AS, Roggeveen Y, van Roosmalen J, Smith H. Factors influencing implementation of interventions to promote birth preparedness and complication readiness. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):270.

Xue D, Qian C, Yang L, Wang X. Risk factors for surgical site infections after breast surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2012;38(5):375–81.

Rücker G, Schwarzer G, Carpenter JR, Schumacher M. Undue reliance on I 2 in assessing heterogeneity may mislead. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):79.

Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Bmj. 1997;315(7109):629–34.

Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994:1088–101.

Dimtsu B, Bugssa G. Assessment of knowledge and practice towards birth preparedness and complication readiness among women in Mekelle, northern Ethiopia: descrptive crossectional. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2014;5(10):4293.

Tura G, Afework MF, Yalew AW. The effect of birth preparedness and complication readiness on skilled care use: a prospective follow-up study in Southwest Ethiopia. Reprod Health. 2014;11(1):60.

Andarge E, Nigussie A, Wondafrash M. Factors associated with birth preparedness and complication readiness in southern Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):412.

Mekuaninte AG, Worku A, Tesfaye DJ. Assessment of magnitude and factors associated with birth preparedness and complication readiness among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic of Adama town health facilities, Central Ethiopia. Eur J Prev Med. 2016;4(2):32–8.

Hiluf M, Fantahun M. Birth preparedness and complication readiness among women in Adigrat town, North Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2008;22(1):14–20.

Hailemariam A, Nahusenay H. Assessment of Magnitude and Factors Associated with Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness among Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Care Services at Public Health Facilities In Debrebirhan Town, Amhara, Ethiopia. Glob J Med Res. 2015;2016.

Belda SS, Gebremariam MB. Birth preparedness, complication readiness and other determinants of place of delivery among mothers in Goba District, bale zone, south East Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):73.

Markos D, Bogale D. Birth preparedness and complication readiness among women of child bearing age group in Goba woreda, Oromia region, Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):282.

Debelew GT, Afework MF, Yalew AW. Factors affecting birth preparedness and complication readiness in Jimma zone, Southwest Ethiopia: a multilevel analysis. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;19.

Iyasu A, Hordofa MA, Zeleke H, Leshargie CT. Level and factors associated with birth preparedness and complication readiness among semi-pastoral pregnant women in southern Ethiopia, 2016. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):442.

Bitew Y, Awoke W, Chekol S. Birth preparedness and complication readiness practice and associated factors among pregnant women, Northwest Ethiopia. Int Sch Res Notices. 2016;2016.

Endeshaw DB, Gezie LD, Yeshita HY. Birth preparedness and complication readiness among pregnant women in Tehulederie district, Northeast Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2018;17(1):10.

Begashaw B, Tesfaye Y, Zelalem E, Ubong U, Kumalo A. Assessment of birth preparedness and complication readiness among pregnant mothers attending ante Natal Care Service in Mizan-Tepi University Teaching Hospital, south West Ethiopia. Clinics Mother Child Health. 2017;14(257):2.

Bishaw W, Awoke W, Teshome M: Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness and Associated Factors among Pregnant Women in Basoliben District, Amhara Regional State, Northwest, Ethiopia, 2013. Primary Health Care: Open Access 2014.

Musa A, Amano A. Determinants of birth preparedness and complication readiness among pregnant women attending antenatal care at Dilchora referral hospital, Dire Dawa City, East Ethiopia. Gynecol Obstetr. 2016;6:2.

Tilahun T, Sinaga M. Knowledge of obstetric danger signs and birth preparedness practices among pregnant women in rural communities of eastern Ethiopia. Int J Nurs Midwifery. 2016;8(1):1–11.

Jatta FO, Lu Y-Y, Chang C-L, Liu C-Y. Pregnant women’s awareness of antenatal danger signs and birth preparedness in rural Gambia. Afr J Midwifery Womens Health. 2014;8(4):189–94.

Mutiso SM, Qureshi Z, Kinuthia J. Birth preparedness among antenatal clients. East Afr Med J. 2008;85(6):275–83.

Bintabara D, Mohamed MA, Mghamba J, Wasswa P, Mpembeni RN. Birth preparedness and complication readiness among recently delivered women in chamwino district, Central Tanzania: a cross sectional study. Reprod Health. 2015;12(1):44.

Mandal T, Biswas R, Bhattacharyya S, Das D. Birth preparedness and complication readiness among recently delivered women in a rural area of Darjeeling, West Bengal. India AMSRJ. 2015;2(1):14–20.

Agarwal S, Sethi V, Srivastava K, Jha PK, Baqui AH. Birth preparedness and complication readiness among slum women in Indore city, India. J Health Popul Nutr. 2010;28(4):383.

Kiataphiwasu N, Kaewkiattikun K. Birth preparedness and complication readiness among pregnant women attending antenatal care at the Faculty of Medicine Vajira Hospital, Thailand. Int J Women's Health. 2018;10:797–804.

Kabakyenga JK, Östergren P-O, Turyakira E, Pettersson KO. Knowledge of obstetric danger signs and birth preparedness practices among women in rural Uganda. Reprod Health. 2011;8(1):33.

Mpembeni RN, Killewo JZ, Leshabari MT, Massawe SN, Jahn A, Mushi D, Mwakipa H. Use pattern of maternal health services and determinants of skilled care during delivery in southern Tanzania: implications for achievement of MDG-5 targets. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2007;7(1):29.

Organization WH. Birth and emergency preparedness in antenatal care, Standards for Maternal and Neonatal Care Geneva, World Health Organization; 2006. p. 1–6.

McPherson RA, Khadka N, Moore JM, Sharma M. Are birth-preparedness programmes effective? Results from a field trial in Siraha district, Nepal. J Health Popul Nutr. 2006;24(4):479.

Fullerton JT, Killian R, Gass PM. Outcomes of a community–and home-based intervention for safe motherhood and newborn care. Health Care Women Int. 2005;26(7):561–76.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all authors of the primary studies included in this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DBK: Conception of research protocol, study design, literature review, data extraction, data analysis, interpretation and drafting the manuscript. CTL, GDK, MAA, PP, and AA: data analysis, reviewing the manuscript, data extraction and quality assessment. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

PRISMA 2009 checklist.

Additional file 2.

Funnel plot of on effect of maternal education on BPCR among pregnant women in Ethiopia.

Additional file 3.

Sensitivity analysis for single study influence on the overall meta-analysis estimate of effect of maternal education on BPCR among pregnant women in Ethiopia.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ketema, D.B., Leshargie, C.T., Kibret, G.D. et al. Effects of maternal education on birth preparedness and complication readiness among Ethiopian pregnant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 20, 149 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-2812-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-2812-7