Abstract

Background

Maternal mortality is high in Ghana, averaging 310 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 2017. This is partly due to inadequate postnatal care especially among rural communities. Ghana can avert the high maternal deaths if women meet the World Health Organisation’s recommended early postnatal care check-up. Despite the association between geographical location and postnatal care utilisation, no study has been done on determinants of postnatal care among rural residents in Ghana. Therefore, this study determined the prevalence and correlates of postnatal care utilization among women in rural Ghana.

Methods

The study utilised women’s file of the 2014 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey (GDHS). Following descriptive computation of the prevalence, binary logistic regression was fitted to assess correlates of postnatal care at 95% confidence interval. The results were presented in adjusted odds ratio (AOR). Any AOR less than 1 was interpreted as reduced likelihood of PNC attendance whilst AOR above 1 depicted otherwise. All analyses were done using Stata version 14.0.

Results

The study revealed that 74% of the rural women had postnatal care. At the inferential level, women residing in Savanna zone had higher odds of postnatal care compared to those in the Coastal zone [AOR = 1.80, CI = 1.023–3.159], just as among the Guan women as compared to the Akan [AOR = 7.15, CI = 1.602–31.935]. Women who were working were more probable to utilise postnatal care compared to those not working [AOR = 1.45, CI = 1.015–2.060]. Those who considered distance as unproblematic were more likely to utilise postnatal care compared to those who considered distance as problematic [AOR = 1.63, CI = 1.239–2.145].

Conclusions

The study showed that ethnicity, ecological zone, occupation and distance to health facility predict postnatal care utilisation among rural residents of Ghana. The study points to the need for government to increase maternal healthcare facilities in rural settings in order to reduce the distance covered by women in seeking postnatal care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Globally, 61% of the 585,000 annual maternal deaths occur within the postnatal stage whereas more than half of these transpire within the first day of childbirth [1]. The situation is worrying in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) where 66% of the global maternal deaths occurred in 2017 [2,3,4]. Inaccessibility and poor postnatal care (PNC) utilisation account for 99% of maternal mortality in low-middle-income countries (LMICs) including SSA, where majority of childbirths occur at home [2,3,4,5].

Similarly, in the Ghanaian context, maternal mortality remains high averaging 310 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births [6] partly due to inadequate postnatal care especially among rural communities [7, 8]. Therefore, Ghana can avert the higher maternal morbidity and associated deaths if women are able to meet the WHO recommended early PNC check-up [9,10,11] which could also facilitate the realization of the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3 [12]. In LMICs, including Ghana, puerperal infections are sometimes undiagnosed due to inadequate PNC follow-up and most postnatal infections occur after being discharged from hospital, which is mostly 24 h after birth [2].

Conventionally, postnatal stage begins immediately after childbirth until 6 weeks (42 days) after birth [13]. The WHO has advised that women should receive at least three postnatal care visits in addition to the first visit which is expected to take place within 24 h of birth. The second visit should fall on day 3, third visit between day 7 and 14, and the last visit before the end of the 6th week [11]. PNC is critical as it helps health professionals to provide comprehensive reproductive health service for women and their babies [1, 2, 14]. During PNC, health professionals are able to evaluate and verify bleeding, examine the breast, control anemia, encourage nutrition and insecticide bed nets, and also educate women on early and exclusive breastfeeding and umbilical cord care [1, 2, 14]. Additionally, through PNC, babies receive services such as birth registration, screening and infection treatment, postnatal growth monitoring and routine immunization services [1, 2, 14].

In spite of these benefits, most women in rural communities are unable to attend PNC [2, 15, 16]. The 2014 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey (GDHS) indicated that 74% of mothers living in rural areas were least probable to receive early postnatal check-up relative to other subgroups. Women in rural areas of Ghana travel 4 km more than urban women to reach a hospital [17]. The same study indicated that a kilometre increase in distance significantly reduces maternal healthcare utilisation [17]. Additionally, it is known that the distribution of health facilities is skewed towards urban centres in Ghana [18]. This presupposes that women in rural communities may be challenged in accessing PNC compared to women in urban locations of the country.

Despite the association between geographical location and PNC utilisation, no national study has been done on determinants of PNC among rural residents in Ghana. Although Adu and colleagues [19] investigated the effects of individual and community-level factors on maternal health outcomes in Ghana and found that rural dwellers were less likely to give birth in health facilities and have PNC compared to urban dwellers, residence was an explanatory variable. Sakeah et al. [20] also explored the role of community-based health planning and services (CHPS) in influencing PNC visits in rural Builsa and the West Mamprusi districts (both in one of the 16 regions) of Ghana and found that women who attended antenatal clinics at least four times and women who had partners with secondary education were associated with at least three PNC visits.

Health facilities and health personnel are concentrated in urban Ghana [18] and as such national level study is required to understand the factors affecting PNC of the rural populace in Ghana. It is against this background that this study seeks to determine the prevalence and correlates of PNC utilization among women in rural Ghana. In the light of the global commitment towards ensuring quality life for persons of all ages [12], this study is of critical public health importance to Ghana. It could guide the Health Promotion and Education Unit and Reproductive and Child Health Department of the Ghana Health Service in preparing and planning for maternal and child health promotion programs that target utilization of maternal health services in rural Ghana.

Methods

Data source

The study utilised women’s file of the 2014 GDHS. The 2014 GDHS, which is the current and sixth edition of the surveys, captures information on prevention and treatment of malaria for children under five, women’s reproductive performance, family planning, maternal and child health and other information relevant for maternal and child health policies. The implementing partners of the survey include the Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), the Ghana Health Service (GHS), and the National Public Health Reference Laboratory (NPHRL) of the GHS with technical aid from the Inner-City Fund (ICF) International. The survey adopted the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) standardised questionnaire which is developed by the Measure DHS programme [16].

The 2014 GDHS used an updated sampling frame which was developed by the Ghana Statistical Service for the 2010 Population and Housing Census. This sampling frame do not include nomadic and institutional populations such as persons in hotels, barracks, and prisons. The survey followed a stratified sampling procedure in order to capture specific indicators at the national level whilst taking into account the rural and urban locations [16].

Firstly, sample points, referred to as clusters constituting enumeration areas (EAs) outlined for the 2010 PHC were selected. This resulted to 427 clusters (i.e. 216 and 211 urban and rural clusters respectively). Secondly, a systematic sampling technique was applied to select households and thereafter, a household listing was undertaken in all the selected EAs. Finally, households to be included in the survey were randomly selected from the list. This led to the selection of approximately 30 households from each cluster. In all, 9656 eligible women (comprising 4753 and 4903 women from urban and rural locations respectively) were identified for the survey. However, a total of 9396 women, consisting of 4602 from urban and 4794 from rural settings were interviewed, leading to 97% response rate. However, the current study was restricted to 1442 rural women with complete information on PNC utilisation and the selected explanatory variables. The study was restricted to rural residents because the 2014 GDHS revealed that the proportion of rural residents (21%) who do not obtain PNC are three times more than urban residents who do not obtain PNC (7%) [16]. Additionally, health facilities and health personnel are concentrated in urban Ghana [18]. Further information about the sampling procedure, pre-testing and field activities are available in the 2014 GDHS report [16].

Definition of variables

Outcome variable

The outcome variable for this study was “Postnatal Care (PNC)”. According to WHO, postnatal stage starts immediately after childbirth and goes into 6 weeks (42 days) after childbirth [13]. Therefore, in the DHS Women’s Questionnaire, all women who had a birth in the 5 years preceding the survey were asked whether a health care provider checked them after giving birth or within 2 months after birth accompanied by ‘Yes’, ‘No’ and ‘Don’t Know’. However, for precision in responses, ‘don’t know’ responses were excluded from the analysis. ‘No’ was coded as ‘0’ signifying those who did not receive postnatal check-up and ‘Yes’ as ‘1’, thus those who had postnatal check-up. PNC plays a key role in maternal health by giving women access to varied reproductive health services [1, 2, 14].

Independent variables

Sixteen independent variables were selected. These are age, marital status, ecological zone, education, wealth status, religion, ethnicity, occupation, total children ever born, partner’s education, frequency of reading newspaper/magazine, frequency of listening to radio, frequency of watching television, health decision making, holds a valid national health insurance scheme (NHIS) card and getting medical help for self: distance is a problem. For clarity of presentation, education was recoded into no education = 1, primary = 2 and secondary or higher = 3; wealth status was recoded into poor = 1, middle = 2 and rich = 3; region of residence was recoded into the three ecological zones of the country, consisting of Coastal = 1, Middle = 2 and Savanna = 3. Occupation was recoded into not working = 1 and working = 2; religion was recoded into Christian = 1, Islam = 2, Traditionalist = 3 and No religion = 4; total children ever born was recoded into one birth = 1, two births = 2, three births = 3 and four or more births = 4 guided by the current total fertility rate of the country [16]. Partner’s education was recoded into no education = 1, primary = 2 and secondary or above = 3; and finally health decision making capacity was recoded into alone = 1 and not alone = 2. These variables were selected because of their theoretical importance and practical significance to maternal healthcare utilisation [21, 22]. Frequency of reading newspaper/magazine, listening to radio and watching television were included in the analysis because they have been found as significant predictors of antenatal care utilisation and skilled birth attendance [23, 24].

Analytical procedure

We first computed the distribution of PNC attendance among women aged 15–49 in rural Ghana. This was followed by a bivariate analysis of socio-demographics and PNC attendance among rural women in Ghana with their respective chi-square of independence test. Since our outcome variable ‘PNC utilisation’ was binary, the binary logistic regression was considered appropriate for the study. This estimation technique was used because it gives room for predictions of outcome variables that are dichotomous in nature. The binary logistic regression was fitted to assess correlates of PNC at 95% confidence interval. Our results was presented in adjusted odds ratio (AOR) and any AOR less than 1 was interpreted as reduced likelihood of PNC attendance whilst AOR above 1 depicts an increased likelihood of PNC utilisation. The weighting factor (v005/100000) inherent in the dataset was applied to cater for the survey sampling errors whilst the ‘linktest’ command and goodness-of-fit were applied to assess the fitness of our model (see Additional files 1 and 2: Appendix 1 and 2 for details). Variance inflation factor (VIF) test for multicollinearity was conducted and the results indicated no evidence of multicollinearity among independent variables (see Additional files 3: Appendix 3). All analyses were done using Stata version 14.0.

Ethical considerations

Since the authors of this manuscript did not participate in the actual data gathering processes, we sought no ethical clearance. However, we sought permission to use the data set from Measure DHS. Meanwhile, Measure DHS reported that ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of ICF International and Ethical Review Committee of Ghana Health Service [16]. Also, they ensured that every information that could reveal respondents’ identities were excluded from the dataset before they released the data to the public domain. The data set is freely available to the public at www.measuredhs.org.

Results

Descriptive results of the study

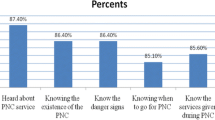

Figure 1 displays distribution of PNC utilisation among women aged 15–49 in rural Ghana. It was found that majority of them (74%) attended PNC, with 26% professing otherwise.

Table 1 presents the results of socio-demographic characteristics and PNC attendance among women aged 15–49 in rural Ghana. Across the age categories, 83% of those aged 45–49 attended PNC and 77% of married women did the same. It was noted that 87% women in the Savanna zone and 72% of those with secondary/higher education utilised PNC. The analysis revealed that wealthier women (81%) and Muslims (86%) utilised PNC.

With respect to ethnicity, PNC utilisation was highest among the Guan (95%). PNC utilisation stood at 76% among women who were working whilst 80% of those who had given birth to two children had PNC. Most women whose partners had no formal education utilised PNC (81%). Eight out of ten of the women who read newspaper/magazine less than once a week (83%) utilised PNC. It was found that majority of those that listened to radio less than once a week utilised PNC (78%), just as majority of those who watched television at least once a week (80%), as indicated in Table 1.

PNC utilisation was phenomenal among women who did not take health decisions alone (77%) and those who did not hold a valid NHIS (82%). It was found that 78% of women who perceived distance as unproblematic utilised PNC. With the exception of age, education, total number of children ever born, frequency of reading newspaper, listening to radio and watching television, the other socio-demographics had statistically significant association with the outcome variable as shown in Table 1.

Correlates of PNC utilisation among rural women aged 15–49 in Ghana

Table 2 depicts correlates of PNC utilisation among women aged 15–49 in rural Ghana. The probability to utilise PNC was higher among women residing in Savanna compared to those in the Coastal zone [AOR = 1.80, CI = 1.023–3.159]. The Guan women were more likely to utilise PNC than the Akan [AOR = 7.15, CI = 1.602–31.935]. More so, women who were working were more probable to utilise PNC as compared to those not working [AOR = 1.45, CI = 1.015–2.060]. Similarly, women who considered distance as unproblematic were more likely to utilise PNC as compared to those who perceived it as problematic [AOR = 1.63, CI = 1.239–2.145]. Finally, from the two model specification diagnoses (see Additional files 1 and 2: Appendix 1 and 2), the final model was well-specified.

Discussion

This study aimed at investigating the prevalence and correlates of PNC utilisation among women aged 15–49 in rural Ghana. In the multivariate regression model, four variables showed significant association with PNC and these are ecological zone, ethnicity, occupation and whether distance to health facility was problematic or otherwise. The direction of significance of these variables are discussed in this section of the manuscript. On ecological zone, we realised that women who resided in the Savanna zone were more probable to utilise PNC as compared to those in the Coastal zone. Comparatively, the Coastal zone is well resourced and endowed with more health facilities and health workforce compared to the Savanna zone [25]. However, this study plausibly strengthens the position of the socio-behavioural model that healthcare utilisation do not only depend on availability of health facilities or services but personal assessment of the need for the service, personal traits and beliefs [26, 27]. Ecological variation has similarly been observed as a determinant of PNC in Malawi [28]. Specifically, they noted that the odds of utilising PNC was 46% less among women in the central region and 53% less among women in the southern region than women in the northern region of Malawi [28].

Our study revealed that Guan women were more probable to utilise PNC than the Akan. Several studies have also found disparity in maternal healthcare utilisation across ethnic lines [29,30,31,32]. In explaining differentials in maternal healthcare utilisation across ethnicity, scholars argue that ethnicity has a link with social stratification in most contexts, and people who belong to ethnic minorities tend to be marginalised and discriminated against, and this adversely affect their prospects of utilising available services and opportunities [33]. However, our study failed to provide reasons why the Guan, being minority, were more inclined to PNC as compared to the Akan. Hence, further studies on ethnicity and utilisation of PNC in Ghana may be required.

We observed that women who were working were more probable to utilise PNC as compared to those not working. The results are in line with a Uganda based study by Ndugga, Namiyonga and Sebuwufu [34] who realised that unemployed women had lower odds of attending postnatal care compared with women who were working. Our results are also congruent with Malawian based study which noted that mothers who were working were 44% more likely to be checked by a professional health worker within 42 days of delivery than women who were jobless [28]. A plausible explanation is that unemployed women are likely to be less endowed economically and as a result may be dissuaded from utilising healthcare due to the associated cost even if such services are recommended by health workers [35, 36]. This may underscore the exigency to create employment avenues and opportunities for women in order to enhance their prospects of utilising PNC.

Finally, in agreement with a previous study [34], the present study revealed that women who viewed distance to health facility as unproblematic were more likely to utilise PNC as compared to those that perceived it as problematic. Malawi based study also indicated that women who perceived that distance to health facility was not a hindrance to their access to health care were more likely to attend early postnatal care than those who perceived distance to the facility as a problem [37]. Izudi et al. [38] also contended that long distances limit the willingness and ability of postpartum women to seek PNC due to the physical difficulties of travel and high cost of motorized transport. The finding highlights the need to reconsider the availability and citing of maternal healthcare services. During the postnatal period, women may be recovering from childbirth and they may not have enough strength to cover long distances [39]. As such, increasing maternal healthcare centers in rural communities and citing these facilities at shorter intervals within communities can substantially reduce the challenge posed by distance.

Strengths and weaknesses

The study utilises data from a nationally representative survey and applies rigorous analytical procedures in estimations. Another key strength of the study is its focus on rural women, a group that have not received much attention as far as studies on PNC in Ghana is concerned. The limitations of the study include the cross sectional study design, which do not allow causal inference. There is also a possible recall bias on the part of the surveyed women.

Conclusions

This study investigated factors associated with PNC among rural residents in Ghana. The study showed that ethnicity, ecological zone, occupation and distance to health facility predict PNC utilisation among rural residents of Ghana. The study has policy and practical implications on maternal healthcare provision in Ghana. First, the study points to the need for government to increase maternal healthcare facilities in rural settings in order to reduce the distance covered by women to access PNC. Second, enhancing empowerment and economic opportunities of women may be required to improve PNC utilisation among the rural populace of Ghana. Further study, preferably qualitative, may be needed to unveil the ethnic driven variation in PNC utilisation among rural women in Ghana.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Measure DHS repository, www.measuredhs.org.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- GDHS:

-

Ghana Demographic and Health Survey

- GSS:

-

Ghana Statistical Service

- GHS:

-

Ghana Health Service

- ICF:

-

Inner-City Fund

- NPHRL:

-

National Public Health Reference Laboratory

- NHIS:

-

National Health Insurance Scheme

- PNC:

-

Postnatal Care

- SDG:

-

Sustainable Development Goal

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

- VIF:

-

Variance Inflation Factor

- WHO:

-

World Health Organisation

References

Hordofa MA, Almaw SS, Berhanu MG, Lemiso HB. Postnatal care service utilization and associated factors among women in Dembecha District, Northwest Ethiopia. Sci J Publ Health. 2015;3(5):686–92.

Langlois ÉV, Miszkurka M, Ziegler D, Karp I, Zunzunegui MV. Protocol for a systematic review on inequalities in postnatal care services utilization in low-and middle-income countries. Syst Rev. 2013;2(1):1–8.

Madaj B, Smith H, Mathai M, Roos N, van den Broek N. Developing global indicators for quality of maternal and newborn care: a feasibility assessment. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95(6):445–452I. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.16.179531.

WHO. Trends in maternal mortality 2000 to 2017: estimates by WHO, UNICEF. Geneva: Geneva, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division; 2019.

McMahon SA, George AS, Chebet JJ, Mosha IH, Mpembeni RN, Winch PJ. Experiences of and responses to disrespectful maternity care and abuse during childbirth; a qualitative study with women and men in Morogoro region, Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):268.

Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), Ghana Health Service (GHS), ICF. Ghana maternal health survey 2017. Accra: GSS, GHS, and ICF; 2018.

Ezeh OK, Agho KE, Dibley MJ, Hall J, Page AN. Determinants of neonatal mortality in Nigeria: evidence from the 2008 demographic and health survey. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:521. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-521.

Kayode GA, Ansah E, Agyepong IA, Amoakoh-Coleman M, Grobbee DE, Klipstein-Grobusch K. Individual and community determinants of neonatal mortality in Ghana: a multilevel analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):165.

Okawa S, Ansah EK, Nanishi K, Enuameh Y, Shibanuma A, Kikuchi K, et al. High incidence of neonatal danger signs and its implications for postnatal Care in Ghana: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0130712. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0130712.

Saaka M, Ali F, Vuu F. Prevalence and determinants of essential newborn care practices in the Lawra District of Ghana. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18(1):173.

WHO. WHO recommendations on postnatal care of the mother and newborn. Geneva: WHO; 2014.

UN. Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. New York: UN Publishing; 2015.

WHO. WHO technical consultation on postpartum and postnatal care (no. WHO/MPS/10.03). Geneva: WHO; 2010.

Lawn JE, Kerber K, Enweronu-Laryea C. 3.6 million neonatal deaths - what is progressing and what is not? Semin Perinatol. 2010;34:371–86.

Neupane S, Doku D. Utilization of postnatal care among Nepalese women. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17(10):1922–30.

GSS GHS, ICF International. Ghana demographic and health survey 2014. Rockville: GSS, GHS and ICF Int; 2015.

Dotse-Gborgbortsi W, Dwomoh D, Alegana V, Hill A, Tatem AJ, Wright J. The influence of distance and quality on utilisation of birthing services at health facilities in eastern region, Ghana. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;4:e002020. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002020.

Dickson KS, Adde KS, Amu H. What influences where they give birth? Determinants of place of delivery among women in rural Ghana. Int J Reprod Med. 2016:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/7203980.

Adu J, Tenkorang E, Banchani E, Allison J, Mulay S. The effects of individual and community-level factors on maternal health outcomes in Ghana. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0207942. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0207942.

Sakeah E, Aborigo R, Sakeah JK, Dalaba M, Kanyomse E, Azongo D, et al. The role of community-based health services in influencing postnatal care visits in the Builsa and the west Mamprusi districts in rural Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:295. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1926-7.

Ameyaw EK, Kofinti RE, Appiah F. National health insurance subscription and maternal healthcare utilisation across mothers’ wealth status in Ghana. Heal Econ Rev. 2017;7(16):2–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13561-017-0152-8.

Ndugga P, Namiyonga NK, Sebuwufu D. Determinants of early postnatal care attendance: analysis of the 2016 Uganda demographic and health survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:163. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-02866-3.

Ogbo FA, Dhami MV, Ude EM, Senanayake P, Osuagwu UL, Awosemo AO, et al. Enablers and barriers to the utilization of antenatal Care Services in India. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(3152):2–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16173152.

Rahman M, Curtis SL, Chakraborty N, Jamil K. Women's television watching and reproductive health behavior in Bangladesh. SSM-Population Health. 2017;3:525–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2017.06.001.

GHS. The health sector in Ghana: facts and figures. Accra; 2016. Retrieved from https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwigmaPZp9btAhUlrXEKHYh2CJIQFjAAegQIAxAC&url=https%3A%2F%2Fghanahealthservice.org%2Fdownloads%2FFacts%2BFigures_2018.pdf&usg=AOvVaw1729Jda2aB8t7kkgvqebNF on July 25, 2020.

Andersen RM, Newman JF. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1973;51:95–124.

Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36:1–10.

Khaki JJ, Sithole L. Factors associated with the utilization of postnatal care services among Malawian women. Malawi Med J. 2019;31(1):2–11. https://doi.org/10.4314/mmj.v31i1.2.

Addai I. Determinants of use of maternal-child health Services in Rural Ghana. J Biosoc Sci. 2000;32:1–15.

Short S, Zhang F. Use of maternal health Services in Rural China. Popul Stud. 2004;58(1):3–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/0032472032000175446.

De Broe S. Diversity in the use of pregnancy-related care among ethnic groups in Guatemala. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2005;31(3):199–205. https://doi.org/10.1783/1471189054483889.

Ganle JK. Ethnic disparities in utilisation of maternal health care services in Ghana: evidence from the 2007 Ghana maternal health survey. Ethn Health. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2015.1015499.

Goland E, Hoa DTP, Målqvist M. Inequity in maternal health care utilization in Vietnam. Int J Equity Health. 2012;11:24. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-11-24.

Ndugga P, Namiyonga NK, Sebuwufu D. Determinants of early postnatal care attendance in Uganda: further analysis of the 2016 demographic and health surveyDHS Working Paper No. 148. Rockville: ICF; 2019.

Chakraborty N, Islam MA, Chowdhury RI, Bari W. Utilisation of postnatal Care in Bangladesh: evidence from a longitudinal study. Health Soc Care Community. 2002;10:492–502.

Izudi J, Amongin D. Use of early postnatal care among postpartum women in eastern Uganda. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2015;129:161–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.11.017.

Kim ET, Singh K, Speizer IS, Angeles G, Weiss W. Availability of health facilities and utilization of maternal and newborn postnatal care in rural Malawi. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:503.

Izudi J, Akwang GD, Amongin D. Early postnatal care use by postpartum mothers in Mundri East County, South Sudan. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:442. https://doi.org/10.1186/2Fs12913-017-2402-1.

Mukonka PS, Mukwato PK, Kwaleyela CN, Mweemba O, Maimbolwa M. Household factors associated with use of postnatal care services. Afr J Midwifery Womens Health. 2018;12(4):189–93.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Measure DHS for making data available and accessible for the study.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FA conceived the study, FA and EKA conducted the formal analysis and interpretation of the results and FA, EKA, TS, JODF, AOD, PK and PAA drafted the manuscript. The authors proof read and approved the final manuscript for important intellectual content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The authors of this manuscript did not participate in the actual data gathering processes, hence, we sought no ethical clearance. However, we sought permission to use the data set from Measure DHS. Meanwhile, Measure DHS reported that ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of ICF International and Ethical Review Committee of Ghana Health Service. Also, Measure DHS anonymised the data set before making it available to the public.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Appiah, F., Salihu, T., Fenteng, J.O.D. et al. Postnatal care utilisation among women in rural Ghana: analysis of 2014 Ghana demographic and health survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 21, 26 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-03497-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-03497-4