Abstract

Background

Birth preparedness and complication readiness has as goal to reduce maternal and neonatal mortality. This concept developed by the organizations of the United Nations permits pregnant women and their families seek health care without delay in case of obstetric complications and delivery. Though its benefits have been proven in several countries, little is known of this in Cameroon and specifically in the North West Region. Therefore, the intention of the study was to assess the awareness and practice of birth preparedness and complication readiness in this health district.

Methods

This was a facility-based cross sectional study carried out in the Bamenda health district of the North West Region, Cameroon. Three hundred forty-five pregnant women of ≥32 weeks gestational age seen at the antenatal consultation units were recruited. The dependent variable was birth preparedness and complication readiness while the independent variables were the socio-demographic and reproductive health characteristics. Data collected was analyzed with SPSS and Microsoft excel. Frequency distributions were used to determine the awareness and practice of birth preparedness and complication readiness.

Results

Of the 345 pregnant women included in this study, 159(46.1%) were aware of birth preparedness and complication readiness. The practice of birth preparedness and complication readiness was unsatisfactory as only 65(18.8%) were considered prepared.

Conclusion

Education and counselling on birth preparedness and complication readiness is not made available to the pregnant women resulting in poor knowledge. Thus, reflected in the low practice of preparation for birth and its complication observed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Maternal mortality is still a major public health problem although globally there has been a decrease [1]. Unfortunately, Cameroon has its maternal mortality ratio (MMR) increased from 430 per 100 000 live births in 1991 to 782 in 201 1[2]. Birth preparedness and complication readiness (BPCR) among other strategies developed by the safe motherhood programme of the United Nations was recognized as a key component in the reduction of maternal and neonatal mortality [3].

Birth preparedness and complication readiness is a comprehensive package to promote timely access to skilled maternal health services. It permits pregnant women and their families seek health care without delay in case of obstetric complications and delivery [3, 4]. Birth preparedness and complication readiness (BPCR) is the process of planning for normal birth and anticipating the actions needed in case of an emergency [3]. BPCR is an essential component of the focused antenatal consultation (FANC) adopted in Cameroon by the Ministry of Public Health to combat the two main delays out of three that are known to be associated with most maternal deaths [5]. It is evident that most of the complications that lead to maternal deaths if treated on time will greatly reduce maternal mortality. The aim of BPCR is to permit pregnant women and their families to overcome the delays that often lead to fatal outcomes due to absence of timely care [3]. BPCR consists of the pregnant woman and her family making active preparation and decision making on identifying a health facility and a skilled birth attendant, saving funds for delivery, emergency and transportation, arranging for mode of transportation, identifying compatible blood donors, arranging necessary article, identifying birth companion and having knowledge on danger signs [2, 3]. Birth preparedness and complication readiness, a strategy to fight this dilemma of maternal and neonatal mortality, is yet to gain its root as a pillar of the focused antenatal consultation. Despite the fact that it is considered as a simple and a practicable means of reducing maternal and neonatal mortality, it is not widely implemented by women and their families as evidenced by maternal deaths still occurring due to delays. Therefore, the objective of this study to provide analysis on the awareness and practice of BPCR among pregnant women in the Bamenda Health District. The results of this study can provide suggestions which may be beneficial in the reduction of maternal morbidity and mortality.

Method

Study design

This was a facility-based cross-sectional study conducted in the Bamenda Health District (BHD) of the North West Region of Cameroon.

Study duration

This study was conducted from February to December, 2016.

Study population

The target population was pregnant women who were at 32 weeks of pregnancy and above and attending ANC at chosen government health facilities in the Bamenda Health District.

Criteria of inclusion

-

Willing and able to give informed consent.

-

Women with ≥32 weeks of pregnancy and attending ANC at the chosen health facilities.

-

At 32 weeks of pregnancy, the women are expected to have made preparations for birth/complications.

Criteria of exclusion

-

Women attending ANC visit for the first time

Sampling method

The non-probabilistic convenience sampling was employed to select the study population. Therefore, any pregnant woman who was eligible and willing to participate was included. The sample size was obtained using the Schlessman formula.

From the above formula, the sample size was 345 women.

Variables

Dependent variable

The dependent variable was birth preparedness and complication readiness. The women were grouped as “prepared” and “unprepared”. Women were considered “prepared” on these seven aspects of BPCR (identify health facility, saved funds for birth/complications, means of transportation in birth/emergency, identify blood donors, packed necessary materials for birth, identified decision-maker and birth companion) while those who had done less than these seven aspects were “unprepared”.

Independent variables

The independent variables to be associated with the dependent variable are:

- Socio-demographic factors (age, level of education, marital status, religion, residence, income).

- Reproductive health factors (parity, gestational age at first ANC, and number of ANC visits).

Data collection tools/technique

The tool for data collection was a structured questionnaire filled by the investigator. The questionnaire was adopted from the survey tools developed by JHPIEGO Maternal Neonatal Health program. A pre-test of the questionnaire was done at the Bamenda Regional Hospital to ensure its feasibility to respond to the objectives of the study.

Two state registered nurses were trained and helped in the data collection. The technique of the data collection was through a face to face interview with the participant to elicit responses if eligibility for the study within the period of data collection. Although the original questionnaires were in English language, pidgin English had to be used for those who could not understand English.

Data processing and analysis

Data collected was coded and entered into Microsoft Excel. It was then transferred and analyzed using SPSS version 20 software. The prevalence of awareness and practice of BPCR were determined from simple frequency distribution. To be considered “prepared”. The woman should have taken seven steps of BPCP plan. Pearson’s chi-square was done to test for association between the dependent variable BPCR and the independent variables. Factors that were found to have p-values below 0.2 were analyzed on bivariate and multivariate logistic regression at 95% confidence interval and p<0.05 were done to identify factors that favor with birth preparedness and complication readiness.

Operational definitions

Birth preparedness and complication readiness: a woman was considered to the prepared for birth/complications if she identified seven of the components of the BPCR items.

Awareness of BPCR: was considered when the woman had heard the term birth preparedness or delivery plan which may be commonly used in our context.

Complications in pregnancy: involves health threats to the unborn baby and the mother.

Knowledge of danger signs in pregnancy: a woman was knowledgeable if she could spontaneously give at least any three danger signs.

Ethical consideration

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Research Ethics Committee for Human Health (CIERSH) at the School of Health Sciences of the Catholic University of Central Africa (reference N° 2016/0431/CEIRSH/ESS/MSR). Administrative clearance was obtained from the Delegation of Regional Health Bamenda.

A written consent form was signed by each participation willing to take part after going through the participant’s information sheet. Parental consent was sought for minors under the age of 16.

Results

A total of 345 pregnant women were included in the interview. They comprised of pregnant women with gestational age ≥ 32weeks. The modal age range was 25 – 34 years with the least aged being 15 years and the most 44 years.

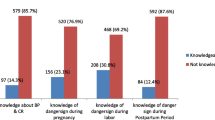

Of the 345 participants in this study, the proportion of pregnant women who had heard of the term birth preparedness was at 46.1%. Even though, only 46.1% acknowledged to have heard of the term birth preparedness, a majority of the pregnant women 308(89.3%) acknowledged to have received some kind of information on preparations to be made during pregnancy from the health workers (Fig. 1). However, only 96(27.8%) testified to this information being provided or followed up at each visit. The proportion of pregnant women with written birth plan was at 6.7%. One hundred and eighty-three (53%) women received information on danger signs in pregnancy, 298(86.4%) received on where to go in case of health problem, 283(82%) on where to give birth, 308(89.3%) on making arrangement for funds, 165(47.8%) were informed to make arrangements for transportation, 102(29.6%) on arrangement for blood donors, 54(15.7%) were asked to choose a desired health worker to deliver the baby, and 231(67%) were informed on signs of labor (Fig. 2). A mean proportion of 58.85% of information on BPCR were acknowledged to have been received by the participants in this study (Table 1). On the knowledge of the possibility of unforeseen health problems that can occur during pregnancy leading to the death of the woman, 305(88.4%) reported that it was possible while 40(11.6%) responded that it was impossible. The pregnant women were questioned on whether they knew any danger signs of pregnancy. Regarding the knowledge of dangers signs, 87.5% indicated that they knew some danger signs and gave examples of them while 12.2% of them did not know any danger signs in pregnancy. Vaginal bleeding was the most frequent mentioned danger sign (73.9%), severe abdominal pain (40.6%), high fever (21.2%), abnormal fetal movements (17.4%), leakage of amniotic fluid before labor (15.7%); difficult breathing (11.3%); swollen hands/face/feet (6.7%), convulsion (5.2%); blurred vision (0.9%), severe headaches (6.7%), severe weakness (6.1%), loss of consciousness (2.6%), and others including severe vomiting, foul-smelling discharge (2.0%) (Table 2).

In the practice of BPCR, 287(83.2%) had saved money/ kept money aside for incurring cost of delivery and obstetric emergencies, 197(57.1%) had identified and made arrangement for means of transportation, 23(6.3%) had identified skilled birth attendant, and 79(22.9%) had identified blood donor. Taking at least seven steps was considered being well prepared. Accordingly, less than one fifth (18.8%) of the pregnant women in this study were considered well prepared for birth and complications (Table 3).

In bivariate logistic regression analysis of the socio-demographic and reproductive health characteristics of the respondents, level of education, occupation, monthly income, number of ANC visits, and knowledge of danger signs in pregnancy were significantly associated with birth preparedness and complication readiness. Multivariate logistic regression showed monthly income (p = 0.013) and number of ANC visits (p = 0.013) to be significantly associated with birth preparedness and complication readiness (Table 4).

Discussion

Awareness of the term birth preparedness was found to be at 46.1% (159 respondents). This is similar to the 46.4% in Oromia region, Ethiopia [6] but lower than the 70.6% in South-eastern Nigeria [7]. The main source of information on birth preparedness was provided by health professionals (89.1%), similar to studies in Ethiopia [8, 9]. Many women (89.3%) acknowledged to have been provided with some information on preparations to be done, higher than the 68.3% reported by [4] in Ethiopia.

Information provided by the health workers included where to go in case of health problem or birth, arrangements of funds, arrangements of transportation. The results obtained were higher compared to those in Ethiopia and Ghana [4, 10]. Up to 70.4% of respondents were not informed on the need to identify blood donors which is high to that of 45.8% and 54.2% in Ghana and Kenya [10, 11]. Information received on the identification of SBA during delivery had the least proportion of 15.7%. The mean value for information received by pregnant women from health providers was at 58.85% which confirms that the awareness of the components of BPCR is low.

The proportion of women who had received information on danger signs was higher than the national proportion of the 2011CDHS and that of a study in the Buea Health District [2, 12] but lower than that of 77% in the North West Region of Cameroon [2] and 90.38% in Ghana [13]. There was low awareness of danger signs indicated in this findings, higher than in Mpwapwa, Tanzania, rural Uganda and others [14,15,16]. The finding is however lower than in Ghana and Ethiopia [17, 18]. The level of education is statistically associated with the knowledge in danger signs where women with university education were three times (OR=3.14; 95% CI: 1.67, 5.93) more likely to be knowledgeable than those with primary education and below, similar to [18] in Ethiopia. This study indicated a low proportion (18.8%) of pregnant women were well prepared for birth and obstetric complications. This is similar to a study in Wolayta zone, South Ethiopia [19] with 18.3% but lower than studies in Ethiopia, Uganda, and Nigeria [6, 15, 20, 21]. The difference in findings may be due to the differences in study population and the number of elements considered for preparedness. Majority of the women had saved money for birth/complications, similar to findings in [22,23,24].

The level education was statistically associated with BPCR on bivariate analysis in this study. Those in the University were six times more likely to prepare for birth or complications in pregnancy (OR = 6.21, 95% CI: 2.70, 14.28) compared to those with primary level and below. Similarities to this finding were seen in studies in Kenya and Nigeria [25]. Occupation was also associated with BPCR (OR = 3.50, 95% CI: 1.58, 7.76). In this study, women who were employed by the government were 3.5times more likely to prepare for birth and complications than those with no employment (students, housewives, farmers). This finding is quite similar to a study in Ethiopia [6]. Monthly income was a predictor of BPCR (AOR = 2.94, 95% CI: 1.39, 6.25). This is consistent with studies in Kenya, Nigeria, India and Uganda [10, 24, 26, 27]. An increase in the average income of an individual has a positive influence on the likelihood of preparing for birth and its complications. This relates to the three delays model where the first delay (decision to seek care) is related to socio-economic and cultural factors. These could be due to the fact that the economic status of the woman gives her the ability to make wise decision and payment on her own than their counterparts. The number of ANC visits is also predictor of birth preparedness (AOR = 2.16, 95% CI: 1.18, 3.90), similar to studies in Tanzania [16, 22] where women who attended at least four ANC visits were approximately two times more prepared than women who attended less. One of the basic assumption stipulated by the concept of BPCR is the fact that the knowledge of danger signs will lead to a greater preparation to minimize effects of complications in pregnancy and child birth. This is so by reducing the first two delays common in untimely care. In this study, women who had knowledge on obstetrics danger signs were more likely to be prepared for birth and its complication compared to those who did not know. The finding of this study showed that knowledge of danger signs is associated with BPCR (OR = 1.95, 95% CI 1.12, 3.38; p = 0.018). This is similar to studies in Nigeria, Ethiopia, India and Uganda [14, 26, 28, 29]. In this study those knowledgeable of danger signs were 1.96times more likely to be prepared than those without.

Conclusion

The findings of the study revealed that the awareness of birth preparedness and complication was low 159 (46.1%). Majority of the pregnant women did not make preparations as required by the BPCR plan. Only 65(18.8%) were prepared according to this study. Insufficient information provided by the health providers and absence of community health workers in the communication of the message on birth preparedness and complication readiness could be attributed to the low status of birth preparedness and complication readiness among pregnant women in this health district.

This study provides an important contribution in the fight against maternal and neonatal mortality. Due to the importance of this subject, a qualitative study to understand why the sufficient preparations are not made can be done in this health district. To the problems identified in this study, the following proposed suggestions have been:

-

Availability and distribution of the delivery plan leaflet to all pregnant women or the plan should be included in the ANC card.

-

Mass media, especially the radio and television, should be exploited in the transmission of the message on BPCR.

-

Community health workers should be trained and included in providing information on BPCR in the community.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ANC:

-

Antenatal consultation

- BHD:

-

Bamenda Health District

- BPCR:

-

Birth preparedness and complication readiness

- CDHS:

-

Cameroon Demographic and Health Survey

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CUCA:

-

Catholic University of Central Africa

- EmONC:

-

Emergency obstetric and neonatal care

- FANC:

-

Focused antenatal consultation

- MMR:

-

Maternal mortality ratio

- MPH:

-

Ministry of Public Health

- NWR:

-

North West Region

- OR:

-

Odds Ratio

- SBA:

-

Skilled birth attendant

- SDG:

-

Sustainable Development Goal

- SHS:

-

School of Health Sciences

- TBA:

-

Traditional birth attendant

- TPB:

-

Theory of Planned Behaviour

- UNFPA:

-

United Nations Population Fund

- UNICEF:

-

United Nations Children’s Fund

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Alkema L, Chou D, Hogan D, Zhang S, Moller AB, Gemmill A, Fat DM, Boerma T, Temmerman M, Mathers C, Say L. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in maternal mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):462–74.

Institut National de la Statistique (INS). Demographic and Health Survey and Multiple Indicators of Cameroon 2011. Calverton: International I; 2012. p. 423.

Del Barco RC. Monitoring birth preparedness and complication readiness. Tools and indicators for maternal and newborn health. 2004. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=3.%09Del+Barco+RC.+Monitoring+birth+preparedness+and+complication+readiness.+Tools+and+indicators+for+maternal+and+newborn+health.++&btnG=.

Hailu M, Gebremariam A, Alemseged F, Deribe K. Birth preparedness and complication readiness among pregnant women in Southern Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e21432.

Ministry of Public Health. Soins obstétricaux et néonatologie d’urgence.

Markos D, Bogale, D. Birth preparedness and complication readiness among women of child bearing age group in Goba woreda, Oromia region, Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014; 14 (282). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-14-282

Ekabua JE, Ekabua KJ, Odusolu P, Agan TU, Iklaki CU, Etokidem AJ. Awareness of birth preparedness and complication readiness in southeastern Nigeria. ISRN obstetr Gynecol. 2011;25:2011. https://doi.org/10.5402/2011/560641.

Henok A. Knowledge towards birth preparedness and complication readiness among mothers who attend antenatal care at Mizan-Aman General Hospital, South West Ethiopia. J Health Med Nurs. 2015;15:51–7.

Musa A, Amano A. Determinants of birth preparedness and complication readiness among pregnant woman attending antenatal care at Dilchora Referral Hospital, Dire Dawa City, East Ethiopia. Gynecol Obstetr. 2016;6(2):356.

Udofia EA, Obed SA, Calys-Tagoe BN, Nimo KP. Birth and emergency planning: a cross sectional survey of postnatal women at Korle Bu Teaching Hospital, Accra, Ghana. Afr J Reprod Health. 2013;17(1):27–40.

Mutiso SM, Qureshi Z, Kinuthia J. Birth preparedness among antenatal clients. East Afr Med J. 2008;85(6):275–83.

Edie GE, Obinchemti TE, Tamufor EN, Njie MM, Njamen TN, Achidi EA. Perceptions of antenatal care services by pregnant women attending government health centres in the Buea Health District, Cameroon: a cross sectional study. Pan Afr Med J 2015;21(1).

Affipunguh PK, Laar AS. Assessment of knowledge and practice towards birth preparedness and complication readiness among women in Northern Ghana: a cross-sectional study. Int J Sci Reports. 2016;2(6):121–9.

Mbalinda S, Nakimuli A, Kakaire O, Osinde M, Kakande N, Kaye D. Does knowledge of danger sign of pregnancy predict birth preparedness? A critique of the evidence from women admitted with pregnancy complications. Health Res Policy Systems. 2014;12(1):60.

Kabakyenga J, Ostergren PO, Turyakira E, Pettersson K. Knowledge of obstetric danger signs and birth preparedness practices among women in rural Uganda. Reproductive Health. 2011;8(1):33.

Urassa D, Pembe A, Mganga F. Birth preparedness and complication readiness among women in Mpwapwa District, Tanzania. Tanzan J Health Res. 2012;14(1).

Acharya AS, Kaur R, Prasuna JG, Rasheed N. Making pregnancy safer – birth preparedness and complication readiness study among antenatal women attendees of a primary health center, Delhi. Indian J Commun Med. 2015;40(2):127–34.

Hailu D, Berhe H. Knowledge about obstetric danger signs and associated factors among mothers in Tsegedie District, Tigray Region, Ethiopia 2013: community based cross sectional study. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e83459.

Gebre M, Gebremariam A, Abebe TA. Birth preparedness and complication readiness among pregnant women in Duguna Fango District, Wolayta Zone, Ethiopia. PLoS one. 2015;10(9):e0137570.

Debelew GT, Afework MF, Yalew AW. Factors affecting birth preparedness and complication readiness in Jimma zone, southwest Ethiopia: a multilevel analysis. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;19.

Idowu A, Deji SA, Aremu OA, Bojuwoye OM, Ofakunrin AD. Birth preparedness and complication readiness among women attending antenatal clinics in Ogbomoso, South West, Nigeria. Int J MCH AIDS. 2015;4(1):47–56.

Bintabara D, Mohamed MA, Mghamba J, Wasswa P, Mpembeni RN. Birth preparedness and complication readiness among recently delivered women in Chamwino district, Central Tanzania: a cross sectional study. Reprod Health. 2015;12(1):44.

Moran AC, Sangli G, Dineed R, Rawlins B, Yameogo M, Baya B. Birth preparedness for maternal health: findings from Koupela district, Burkina Faso. J Health Popul Nutri. 2006;24(4):489.

Agarwal S, Sethi V, Srivastava K, Jha PK, Baqui AH. Birth preparedness and readiness among slum women in Indore city, India. J Health Popul Nutr. 2010;28(4):383–91.

Tobin EA, Ofili AN, Enebeli N, Enueze O. Assessment of birth preparedness and complication readiness among pregnant women attending Primary Health Care Centres in Edo State, Nigeria. Ann Nigerian Med. 2014;8(2):76–81.

Iliyasu Z, Abubakar IS, Galadanci SH, Aliyu MH. Birth preparedness and fathers’ participation in maternity care in northern Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2010;14(1).

Kabakyenga J, Ostergren P, Turyakira E, Pettersson K. Influence of birth preparedness, decision-making on location of birth and assistance by skilled birth attendants among women in south-western Uganda. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35747.

Hiluf M, Fantahun M. Birth preparedness and complication readiness among women in Adigrat Town, North Ethiopia. Ethiopia J Health Dev. 2008;22(1):14–20.

Deoki N, Kushwah SS, Dubey DK, Singh G, Shivdasani S, Adhish V. A study for assessing birth preparedness and complication readiness intervention in Rewa District of Madhya Pradesh Chief Investigator, India. Rewa: Department of Community Medicine, SS Medical College; 2008. p. 9.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all who participated in this research.

Funding

There was no funding for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YPI, PMT, CNN, MAV, FB and SNC designed the study and were involved in all aspects of the study. PMT supervised the study. YPI, FB, SNC and CNN contributed to scientifically reviewing the manuscript for intellectual inputs and review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Research Ethics Committee for Human Health (CIERSH) at the School of Health Sciences of the Catholic University of Central. Africa (reference N° 2016/0431/CEIRSH/ESS/MSR). Administrative clearance was obtained from the Regional Delegation of Public Health in Bamenda. A written consent form was signed by each participation willing to take part after going through the participant’s information sheet. Parental consent was sought for minors under the age of 16.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ijang, Y.P., Cumber, S.N.N., Nkfusai, C.N. et al. Awareness and practice of birth preparedness and complication readiness among pregnant women in the Bamenda Health District, Cameroon. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 19, 371 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2511-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2511-4