Abstract

Background

Eliminating disrespect and abuse in health care facilities during childbirth could be a contributory factor in improving pregnancy outcomes and avoiding preventable illnesses and deaths. This study aims to provide evidence of disrespect and abuse in this community in order to create awareness about its occurrence.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was carried out on 384 recently delivered women who visited the postnatal and immunization clinics of a primary and tertiary health facility in Ile-Ife. Information was sought about awareness of disrespect and abuse, prevalence and forms of disrespect and abuse, and opinions on improvements which can be made in maternity services. Univariate analysis was used to summarise the data.

Results

About half of the respondents were in their fourth decade of life and had tertiary education. Overall, the majority (98.4%) of respondents agreed that it was their right to be treated with respect and dignity during childbirth while about one-fifth (19%) had ever experienced some form of disrespect and abuse. The commonly identified forms of disrespect and abuse were: non-dignified care (12.8%), discrimination (8.1%), a detention and abandonment (6%). However, the majority (81%) of the respondents did not have any suggestions for improvements in delivery services.

Conclusions

Although most of the respondents knew it was their right to be treated with respect, some reported that they had experienced disrespect and abuse during childbirth in varying forms. The evidence from this survey draws attention to the need for interventions to address the health system factors hindering health service utilization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In March 2010, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) funded Translating Research into Action (TRAction) project, called for a meeting of public health and human rights governmental and non-governmental organisations who were active in maternal health issues to review the subject of respectful and disrespectful birth care including abusive maternal care [1]. This was motivated by the understanding that disrespect and abuse during childbirth not only involves human rights violations but is also one of the barriers to the utilization of a skilled birth attendant at delivery [1,2,3]. Over the last twenty years, efforts have gone into improving the number of deliveries taken by a skilled birth attendant in order to reduce morbidity and mortality. These efforts have yielded positive results as the proportion of deliveries attended by a skilled birth attendant in developing countries have increased from 56% in 1990 to 62% in 2012 however, 800 women and 7700 newborns still die daily from complications during pregnancy, delivery and postpartum period [4].

For a long time, the focus regarding barriers to skilled care has been on access to care until it was realised that improved access doesn’t necessarily translate to active use. Thus, shifting the focus to quality of care in terms of not just the skill of health workers, but also with regards patient’s rights and their perceptions of the quality of care they received [2, 3]. On-going research reveal that pregnancy outcomes are also linked to the experience of care and to reduce preventable illnesses and deaths, health care delivery should not only involve good infrastructure and skill but also proper delivery in a gentle, caring way and with the right attitude [4].

The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined a quality of care and prepared a framework for providing optimum care for mothers and newborn around the time of pregnancy, delivery and postpartum because they realized that adequate care in this period contributes maximally to saving lives [4]. According to WHO, Standards for improving the quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities [4]:

“The quality of care for women and newborns is therefore the degree to which maternal and newborn health services (for individuals and populations) increase the likelihood of timely, appropriate care for the purpose of achieving desired outcomes that are both consistent with current professional knowledge and take into account the preferences and aspirations of individual women and their families”.

The framework divides quality of care into two parts: the provider’s provision of care and the patient’s experience of care. Embedded in the patient’s experience of care is a section on standards of care [4] with one of the domains stating that “women and newborn receive care with respect and preservation of their dignity” [p.3]. This is meant to address all forms of abuse, discrimination, neglect, detainment, and services denial [2, 4].

There have been reports of disrespect and abuse during labour and delivery from around the world and this occurrence has been defined “as interactions or facility conditions that local consensus deems to be humiliating or undignified, and those interactions or conditions that are experienced as or intended to be humiliating or undignified” [5]. The seven categories of disrespectful maternity care which have been highlighted by Browser and Hill in their landmark paper on the analysis of disrespect and abuse are: physical and verbal abuse, non-consented clinical care, non-dignified care, discrimination, non-confidential care, abandonment and detainment in a health facility. These may be due to behavioural and structural factors. Evidence from literature suggests that behavioural factors may be linked to learned behaviour from pre-service training, the belief that healthcare workers are acting in the best interest of patients, and a possible lack of commitment to ethics and respect for human right concerns of their patients [1, 6, 7]. Furthermore, many authors have also noted that structural challenges including under-staffing, poor pay and poor facility space, may lead to disrespectful maternity care [2]. Disrespect and abuse have been recorded in sub-Saharan Africa. Findings from Kenya revealed that 20% of the women polled reported some form of disrespect and abuse during their maternity care ranging across six categories which includes: non-consented care, abandonment and detainment, non-dignified care, physical abuse and non-confidential care. They perceived they were humiliated when receiving care during their labour and deliveries [8]. In Ghana, a study on exposure to disrespectful maternal care among final year student midwives had 72% opining that maltreatment during labour was a problem and they reported that the occurrence was more in government facilities compared with private facilities. About 80% of respondents also reported that the way women were treated during their labor and delivery influenced their choice of a delivery place, a probable reason why many women decided to deliver at home [9].

Disrespectful and abusive care has also been recorded in Nigeria. Okafor, Ugwu, and Obi in 2012 noted that 98% of their respondents reported one form of disrespectful and abusive care in their last delivery. This ranged from non-consented and non-dignified care to abusive care and abandonment and the commonest was the non-consented care and physical abuse. Non-consented care was carried out for procedures such as episiotomies, blood transfusions and caesarean sections and physical abuse included being beaten, slapped, restrained and tied as well as incidences of sexual abuse by health workers [10]. In Abuja, north-central Nigeria, Bohren et al. interviewed patients, health workers, and other hospital staff who observed patients being slapped, threatened, shouted at and physically restrained while on admission. Although some viewed this type of behavior as unacceptable, however, few of them believed actions like these were necessary in order to motivate the women to comply with care to ensure healthy outcomes. Some alleged that slapping was necessary to give the woman “more strength to push the baby out” [7].

In the face of evidence which proves the presence of disrespect and abuse in maternity care, the concept of Respectful Maternal Care (RMC) has evolved from the safe motherhood initiative and supported by USAID along with the White Ribbon Alliance. It is “an approach centred on the individual, based on principles of ethics and respect for human rights, and promotes practices that recognize women’s preferences and women’s and newborns needs” [11].

A few studies have shown that some of the victims of disrespectful and abusive maternity care sometimes accept the abuse they get as rightfully deserved, acceptable, and may not recognize any infringement on their fundamental human rights. Some regard this kind of behavior as “normal” and come to expect it [1, 7, 9].

In spite of available evidence of disrespect and abuse of women in facility-based childbirth care, there are few interventions geared towards reducing disrespectful and abusive care and promoting respectful maternal care in this environment. There is the need to create awareness by providing data and proof of its occurrence. This study is aimed at providing empirical evidence to support the growing trend of reports from other research sources carried out in other parts of the country and in the West African Sub-region. Studies done in Nigeria are few and none of them provide information about the South West geopolitical zone. It is also aimed at investigating the existence and magnitude of disrespect and abuse of women during childbirth from the client’s perspective in health facilities in Ile-Ife, south West Nigeria.

Methods

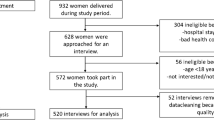

This was a descriptive cross-sectional survey. Respondents were recruited for the survey at the postnatal and immunization clinics of a primary and a tertiary public health facility in Ile-Ife, Osun state and these were women who booked for antenatal care and had facility-based delivery in the selected facilities. Using the WINPEPI software’s formula for estimating a proportion and a prevalence of 20% from a similar study in Tanzania, at a 95% confidence level, 5% level of significance and a 20% attrition rate, a minimum sample size of 303 was determined. For a robust analysis, 400 questionnaires were eventually administered. As women presented in the immunization or postnatal clinic, they were recruited by trained research assistants until the sample size of 400 was met. Of the 400 questionnaires administered, 384 were returned completed while 16 were discarded due to mothers not completing the interview and hurrying to leave the facility after receiving clinical care giving a response rate of 96%. Inclusion criteria were all women who had recently had a baby in the last three months while women who did not deliver in the health facilities were excluded. Interviews were conducted for eligible respondents who were serially recruited over a period of two weeks in the order of their registration at the selected clinics.

A pre-tested interviewer-administered semi-structured questionnaire was used to collect information on awareness of respondents about disrespect and abuse among women who had facility-based childbirth and the prevalence of this disrespect and abuse. Prevalence was defined as “ever experience” of disrespect during childbirth for each respondent interviewed. Questions were also asked about the different forms of disrespect and abuse they had experienced as well as their opinion on areas for improvement in maternity services. The questionnaires were administered by trained interviewers and the questions were translated into the Yoruba language and back-translated into the English language to ensure accuracy in the portrayal of the intended meaning. Interviews were conducted in the Yoruba language for those who could not speak the English language. Participation was voluntary, confidentiality was assured and verbal consent was obtained from respondents before interviews were conducted.

Data were field edited then entered and analysed using SPSS version 17. Univariate analysis to generate frequency tables was performed for socio-demographic characteristics, awareness about disrespect and abuse in facility-based childbirth, the prevalence of disrespect and abuse, the different forms of disrespect and abuse they experienced and their opinion regarding areas of improvement in maternity services. Responses to open-ended questions were grouped into similar categories, transformed into quantitative variables then frequencies were determined.

Results

A total of 384 women were recruited into the study. Their ages ranged from 15 years to more than 50 years with more than half of them (51%, N = 177) in the 30–39 year age group. Another half of them (52.7%, N = 202) had a tertiary education while almost half (49.2%, N = 189) were either artisans or traders. More than 7 in 10 of them were Christians and more than 8 in 10 were Yoruba (Table 1).

As shown in Table 2, more than 9 in 10 of them said that it was not culturally acceptable to be disrespected or abused during childbirth. About the same proportion agreed that it was their right to be treated with respect and dignity while 11% (N = 44) of them reported knowing someone who had been treated disrespectfully or abused during childbirth.

Table 3, which was developed from the question “Have you ever been disrespected or abused during maternity care?” revealed that one-fifth (19%, N = 73) of respondents had ever experienced disrespect and abuse during childbirth. In Table 4, respondents identified the different forms of disrespect and abuse they had experienced. The commonest form was the non-dignified care (12.8%, N = 49) followed by discrimination (8.1%, N = 31) and the least identified was physical abuse (1.6%, N = 6).

Different forms of physical abuse were experienced by 6 out of the 384 respondents which include being pinched or beaten (50%, N = 3) respectively while 33.3%, N = 2 were either slapped or sexually abused (Table 5).

The forms of non-consented care are shown in Table 6, as experienced by 18 out of 384 respondents, and was more commonly about lack of information on the care received (77.8%, N = 14).

Table 7 describes the non-confidential care received among respondents. The commonest was about asking private questions in the presence of other patient or healthcare workers not directly providing service to respondents (60%) while the least was taking delivery in the presence of other patients and their relatives (15%).

Table 8 described the different forms of abandonment and detention and 7 in 10 of the respondents who experienced disrespect and abuse said they were left unattended during delivery and were denied necessary care which they expected in form of prompt response when they requested for medical attention or the constant presence of healthcare workers in the delivery room. Out of the 23 women who responded to question on being detained due to inability to pay hospital fees, 2 said yes, they had been detained.

In Table 9, the non-dignified care which occurred most was being shouted at (59.2%) while the use of harsh tone and words was a close second (49%). The least form was being threatened (6.1%).

Regarding forms of discrimination, Table 10 showed that perceived discrimination occurred most commonly due to economic status (38.7%) and least commonly due to HIV/AIDS status (6.5%).

Table 11 summarises the suggestions by respondents on improvement of maternity services in three areas: ANC services, delivery services and attitude of staff. In the three areas, 20 to 25% of respondents suggested promptness of services, improved care and increased staffing as ways to improve maternity services.

Discussion

As demonstrated by this study, obstetric abuse is a reality that occurs against women delivering in identified facilities in Ile-Ife that might hinder achieving the coverage goals for reducing maternal mortality. This study found the prevalence of disrespect and abuse during childbirth in a local government area in Ile-Ife to be 19%, similar to findings in other studies conducted in Tanzania [12] and Kenya [6] reporting a prevalence of 19.5 and 20% respectively. However, a study conducted in Enugu, South Eastern Nigeria [10] reported a prevalence of 98 % suggesting a possible regional or cultural link with respectful maternal care.

This prevalence was despite a high level of awareness by respondents of abuse during childbirth being culturally unacceptable (97.0%), a finding in congruence with Nigeria’s adopted National Standard of Care for Public health facilities, the Charter on Universal Rights of Childbearing Women which does not condone disrespect and abuse in childbearing [2]. An even higher proportion (98.4%) considered respectful and dignifying maternal care a right during childbirth, again, a typical finding in other studies where respectful maternal care is considered a fundamental right of women [13, 14].

Just over 10% of respondents reported knowing someone who had been abused during childbirth which is much lower than reported by midwifery students in Ghana who reported witnessing obstetric abuse at a much higher rate (78.0%) in the maternity rooms [9]. This difference may be due, in part, to the proximity of midwifery students to the childbirth process and low reporting by women who may consider the process as normal or try to move on from an unpleasant experience.

This study found non-dignified care to be the highest form of abuse reported at 12.8% and this was typified, from the opinion of respondents, as being shouted at, use of harsh words or tone or being insulted during the birth process. Present but much less reported was intentional humiliation and threats. Because treatment with dignity determines to a great extent utilization of these facilities, women who have received non-dignified care may prefer to deliver elsewhere. Being discriminated against on account of socio-demographics like economic status, age, educational level, ethnicity, marital and HIV status was also a key finding in this study which is supported by findings in nearby Ibadan, Nigeria that found an association between experience of violence and socioeconomic status [15], however, Innocent et al. in Enugu, Nigeria did not find any significant association between maternal socio-demographic and disrespectful maternal care. Despite being reported as a distasteful practice in facility-based delivery [4, 10], abandonment was also reported by 6% of the respondents, generally as being left unattended or denied necessary care with fewer reports of lack of encouragement during delivery and detainment on account of inability to pay for services. Non-confidential care, which is an unacceptable breach of the code of ethics in healthcare, was found in this study to include being asked private questions publicly, physical examination without a screen and delivery in public view. The report of non-consented care due to inadequate information about care and procedures was low and this may be as a result of increasing awareness among healthcare providers that non-consented care may result in litigation. Physical abuse, however, was least reported by respondents (1.6%) mainly as being pinched, beaten, slapped or sexually abused, however, a single occurrence of sexual abuse is an important issue which needs to be highlighted. These findings are proportionately similar to findings in Kenya [8] and Tanzania [12, 16] though findings from this study seem significantly less than those found in these climes, again likely due to a rising awareness of litigation among care providers.

Respondents in this study suggested kindness from care providers and prompt service as a recipe for improving maternal services, particularly antenatal and delivery services, which are important ways of not stereotyping violence as a part of obstetric care as suggested in other studies [14]. Increased staffing was also suggested, in keeping with identified policy approaches to reducing disrespectful maternal care [2, 4].

Exit interviews were conducted for women who had live born children and were attending postnatal clinics or who brought their children for immunization. Possible limitations of this includes exclusion of the experience of mothers who had stillbirth or and early neonatal death, recall bias and social-desirability bias whereby respondents are likely to give information considered favourable. Another bias which could have occurred is in relation to recruitment (selection) bias as some of the respondents were recruited from postnatal clinics which mothers who may have encountered disrespect and abuse during their deliveries may be unwilling to attend. As women deliver in both formal and informal delivery facilities in Ile-Ife, the demographics of women attending the clinics selected may not completely reflect the demographics of pregnant women in city, and this is a possible limitation to the generalizability of the study. Also, in considering disrespect and abuse as a single item, this conflation may have a possible effect on study validity. A qualitative study could also have been conducted to provide in-depth information regarding the topic beyond the a priori list of categories of disrespect and abuse that were used for the survey. Lastly, discarded responses from the few respondents who were rushing to leave the clinic after receiving services may also pose a limitation.

Conclusion

This survey revealed varying forms of the occurrence of disrespect and abuse during childbirth in health facilities in this community. It adds to the growing evidence which reveals that poor access to health care services might also be as a result of treatment received by women in these facilities and draws attention to the need for interventions to address the system factors hindering health services utilization.

Abbreviations

- AIDS:

-

Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome

- ANC:

-

Ante-Natal Care

- HIV:

-

Human lmmuno-deficiency Virus

- RMC:

-

Respectful Maternal Care

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for Social Sciences

- TRAction:

-

Translating Research into Action

- USAID:

-

United States Agency for International Development

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Bowser D, Hill K. Exploring Evidence for Disrespect and Abuse in Facility-Based Childbirth Report of a Landscape Analysis. Harvard Sch Public Heal Univ Res Co, LLC [Internet]. 2010:1–57.

Hastings MB. Pulling back the curtain on disrespect and abuse: the movement to ensure respectful maternity care. White Ribb Alliance. 2015:1–8.

Warren C, Njuki R, Abuya T, Ndwiga C, Maingi G, Serwanga J, et al. Study protocol for promoting respectful maternity care initiative to assess, measure and design interventions to reduce disrespect and abuse during childbirth in Kenya. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth [Internet]. 2013;13:21. Available from: http://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2393-13-21

World Health Organization. Standards for improving the quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities; 2016. p. 73. Available from: http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/249155

Freedman LP, Ramsey K, Abuya T, Bellows B, Ndwiga C, Warren CE, et al. Defining disrespect and abuse of women in childbirth: a research, policy and rights agenda. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92:915–7.

Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Hunter EC, Lutsiv O, Makh SK, Souza JP, et al. The mistreatment of women during childbirth in health facilities globally: a mixed-methods systematic review. Jewkes R, editor. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001847.

Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Tunçalp Ö, Fawole B, Titiloye MA, Olutayo AO, et al. “By slapping their laps, the patient will know that you truly care for her”: a qualitative study on social norms and acceptability of the mistreatment of women during childbirth in Abuja, Nigeria. SSM - Popul. Heal. [internet]. Elsevier. 2016;2:640–55 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.07.003.

Abuya T, Warren CE, Miller N, Njuki R, Ndwiga C, Maranga A, et al. Exploring the prevalence of disrespect and abuse during childbirth in Kenya. PLoS One. 2015;10:1–8.

Moyer CA, Rominski S, Nakua EK, Dzomeku VM, Agyei-Baffour P, Lori JR. Exposure to disrespectful patient care during training: data from midwifery students at 15 midwifery schools in Ghana. Midwifery [Internet]. Elsevier; 2016;41:39–44. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2016.07.009

Okafor II, Ugwu EO, Obi SN. Disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth in a low-income country. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. [Internet]. International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2014;128:110–3 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.08.015.

Reis V, Deller B, Carr CC, Smith J. Respectful Maternity Care: Country Experiences. Surv Rep. [Internet]. 2012;1–42. Available from: https://www.k4health.org/sites/default/files/RMCSurvey Report_0.pdf.

Kruk M, Kujawski S, Mbaruku G, Ramsey K, Moyo W. Freedman. Disrespectful and abusive treatment during facility delivery in Tanzania: a facility and community survey. Health Policy Plan. 2014:1–8.

Vogel JP, Bohren MA, Tunçalp Ö, Oladapo OT, Adanu RM, Baldé MD, et al. How women are treated during facility-based childbirth: development and validation of measurement tools in four countries - phase 1 formative research study protocol. Reprod. Health [Internet]. Reprod Health; 2015;12:60. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4510886&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract.

Vacaflor CH. Obstetric violence: a new framework for identifying challenges to maternal healthcare in Argentina. Reprod Health Matters. 2016;24:65–73.

Fawole OI, Asekun-Olarinmoye EO, Osungbade KO. Are very poor women more vulnerable to violence against women? Comparison of experiences of female beggars with homemakers in an urban slum settlement in Ibadan, Nigeria. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24:1460–73.

Ratcliffe HL, Sando D, Mwanyika-Sando M, Chalamilla G, Langer A, McDonald KP. Applying a participatory approach to the promotion of a culture of respect during childbirth. Reprod Health [Internet]. 2016;13:80. Available from: http://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12978-016-0186-0

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the participants in this study for their cooperation in providing the necessary information.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MYI is the PI and was involved in the concept design of the research title, drafting, reorganization and revision of the manuscript. EAO, OO, ESO, IFI, FAT, and FOC were all involved in data collection, analysis, and revision of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was given by the Research and Ethics Committee of the Institute of Public Health, Obafemi Awolowo University, and protocol number IPHOAU/12/99. Verbal consent was obtained from each participant prior to data collection as well as the legal guardian of those less than 18 years. This was also approved by the Ethics and Research Committee.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ijadunola, M.Y., Olotu, E.A., Oyedun, O.O. et al. Lifting the veil on disrespect and abuse in facility-based child birth care: findings from South West Nigeria. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 19, 39 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2188-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2188-8