Abstract

Background

With an increasing number of institutional deliveries, the Nepalese health system faces a challenge to ensure a quality of service provision. This paper aims to identify the determinants of client satisfaction with maternity care in Nepal using data from a nationally representative health facility survey.

Methods

A total of 447 exit interviews, with women who had either recently delivered or who had experienced obstetric complications, were conducted across 13 districts in Nepal (87% in hospitals, 8% in Primary Health Care Centres (PHCCs), and 5% in Sub/Health Posts(S/HPs). Client satisfaction was measured using an eight item scale that covered accessibility, interpersonal communication, physical environment, technical aspect of care and decision making. A client satisfaction index was computed using ordinal principal component analysis. A multivariate probit model was used to assess the net effect of explanatory variables on client satisfaction.

Results

Longer waiting times and overcrowding increased the likelihood of dissatisfaction. Having an opportunity to ask questions was positively associated with client satisfaction. Respondents from hill districts and rural areas were more likely to be satisfied in comparison to respondents from mountain, terai and urban areas. Socio-demographic factors (age, parity, caste/ethnicity, education, and ecological zone) and supply side factors (the time taken to reach a facility, type of facility, payment for services, and unknown heath worker or anyone entering the delivery room) were not statistically associated with satisfaction.

Conclusions

The findings suggest client satisfaction with the quality of maternity services in Nepal could be improved by reducing waiting times and overcrowding, and giving the mothers adequate time to ask questions. If clients are more satisfied they are more likely to use the facility again/recommend to a friend.

Similar content being viewed by others

Backgroud

Satisfaction with maternity care is a multidimensional construct embracing satisfaction with self (personal control), and with the physical environment of delivery room and quality of care [1]. Aspects of care that may influence client satisfaction include: provider attitude, provider competence, outcome, physical environment, continuity of care, access, information, cost, bureaucracy and attention to psychosocial problems. Quality of care may not always be linearly associated with the level of satisfaction as perceived by the clients [2], however, client satisfaction is an important determinant of utilization of health services and the choice of health facility [3], it is important to know clients’ views and experiences while designing health programmes [4]. Client satisfaction also impacts the viability and sustainability of health care services, and is an important input for regular monitoring and quality improvement in health care delivery systems.

Hospital-based maternity care has contributed towards the reduction in maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity in developing countries [5, 6]. With the increasing rates of institutional deliveries, poor countries are now facing a challenge to ensure good quality maternity care [7]. Access to and availability of institutional delivery care alone is not enough to achieve the desired goals in maternal and child health, it is also the quality of care that saves lives of mothers and newborns. Although client satisfaction is not directly addressed in the Nepal Health Policy 1991 [8], the Nepal Health Sector Programme-2 (NHSP-2: 2010–2015), includes client satisfaction as an essential component of health service delivery [9]. The newly released National Health Policy aims to develop an accountable health system that includes a mechanism to collect client complaints/feedback [10]. Several studies have described the determinants of clients’ satisfaction with maternity care in other countries [2, 11,12,13,14]. Women who are treated with respect, courtesy and dignity, and have trusting relationships with their care providers are more likely to be satisfied [15]. Lack of involvement in decision making and inadequate information about their care are associated with dissatisfaction [16]. Older people more commonly report satisfaction with maternity care [12,13,14, 17]. Compared to the service tracking survey 2012 (STS 2012), which showed 90% of clients satisfied/very satisfied) [18], STS 2013 showed a slightly lower satisfaction (86%) to maternity services [19]. Similarly, slightly higher percentage of maternity clients (4%) mentioned not willing to visit the facility again in STS 2013 [19] compared to STS 2012(3%) [18]. The two studies cited above (STS 2012 and STS 2013) have only looked into the percentage of clients satisfied but have not explored the determinants. This study will be helpful to address the knowledge gap regarding determinants of maternity clients satisfaction in the Nepalese context and similar settings.

Methods

Data source and sampling

This study is the secondary analysis of the survey data obtained as part STS 2013 conducted by the Ministry of Health (MoH), Nepal. The survey incorporated a facility questionnaire, and maternity and outpatient exit interviews. The primary objective of the survey was to provide national estimates for key reproductive, maternal, neonatal and child health indicators related to service availability, readiness and distribution of public (not private) sector of Nepal.

Nepal consists of 75 districts divided into three ecological zones (mountain, hill, and terai), or five administrative regions. For the purposes of the study design these ecological zones and administrative regions were amalgamated to form 13 sub-regions. The survey used a two-stage sampling design. In the first stage, one district was randomly selected from each of 13 sub-regions and these districts were the Primary Sampling Units (PSUs). This resulted in three districts being selected from the mountain region, five from the hill region, and five from the terai region, which are considered as strata for this study. In the second stage, the facilities were selected within each of the 13 districts. The higher the level of facility, the greater the probability of being selected: all public hospitals (17) and primary health care centres (PHCCs) (39) from the selected districts were included and an Equal Probability Sampling Method (EPSEM) was used to select health posts (HPs) (100/208) and sub-health posts (SHPs) (68/490). All maternity clients from PHCCs, HPs and SHPs attending the course of 2 days, and up to five clients per hospital, were interviewed. More details on the methodology are presented in the STS 2013 final report [20].

A total of 447 women who delivered at the facility or sought care for intra-partum complications were interviewed across the 13 districts (87% in hospitals, 8% in PHCCs, and 5% in S/HPs.). All clients who participated in exit interviews had received inpatient services. The smaller percentage of interviews at lower level facilities reflected the lower caseload.

Data collection and quality assurance

Data collection was performed from July to August 2013. A total of 43 enumerators and 13 field supervisors were recruited for data collection. All of the field researchers had some experience of research/data collection, and had an academic background in health sciences (public health, nursing, medicine, sociology).

A Training Manual, Survey Field Manual, and Data Entry Manual were produced and used across the training period, data collection period, and data entry period, respectively to maintain quality and consistency in the work. Enumerators received 5 days of training. Supervision and monitoring visits from the Government of Nepal and Nepal Health Sector Support Programme (NHSSP) were carried out to identify and rectify any problems. During supervisory visits, some cases of non-compliance to survey manuals were observed. Feedback was provided during data collection and was also circulated to all of the district supervisors by telephone. Field teams could contact the central support team by mobile phone whenever necessary.

During fieldwork, all completed questionnaires were checked by the supervisors in the district before sending them to the central office for data entry. Feedback was provided to the enumerators during data collection.

Data cleaning, coding and entry

Before data entry, consistency checks and content cleaning were carried out and outliers in continuous variables were checked. Any suspect data were cross-checked against hard copies of completed questionnaires. The database was developed in CSPro 5.0 and pre-tested before data entry started.

Measures

Client satisfaction

Client satisfaction was measured by an eight-item instrument. The items covered key dimensions of client satisfaction: accessibility (one question), interpersonal communication (two questions), physical environment (two questions), clinical care (two questions) and decision making (one question). The responses were marked using a five-point Likert scale [21]: (1) very dissatisfied, (2) dissatisfied, (3) Neutral, (4) satisfied and (5) very satisfied. Different client satisfaction surveys have focused on different elements of client satisfaction. The eight items used in this survey aim to measure the key elements of the client’s experience of maternity care [22] and had a high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.74). Similar questionnaires were used in the previous rounds of the STS, conducted in 2011 and 2012, [18, 23] although some minor modifications were made to the 2013 STS questionnaire compared to earlier surveys.

The client satisfaction index was computed from the eight domains presented in Appendix, using the ordinal Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [24], since the variables were measured in the ordinal scale. A previous study has shown the agreement between observed satisfaction and predicted satisfaction using PCA [25]. A spearman correlations of the predicted overall satisfaction level was assessed with the observed satisfaction domains in this study and presented in Appendix.

To conduct bivariate and multivariate analysis the five point Likert scale was dichotomized: scores of four or five were counted as satisfied whereas one to three were counted as a not satisfied. The rationale behind the dichotomization was to yield a simple outcome variable which allows for complex tests of predictors.

Explanatory variables

Individual characteristics (mother’s age, education and caste/ethnicity), cluster characteristics (ecological zone and place of residence), access to health facilities (reaching and waiting time), facility type, clinical care (mode of delivery and breastfed within an hour), advice and information (danger signs for mothers and newborns, exclusive breast feeding, comfort with the sex of the provider, family planning and being given the opportunity to ask questions), overcrowding within maternity departments, and the cost of care. Waiting time in this article refers to the duration of time between arriving at the facility and the first check-up by a service provider.

Data analysis

Data analysis took into account the selection of districts within the strata defined by the ecological zones (mountain, hill and terai) and acknowledged the weighting of the data, the approximate stratification, and the clustering (health facilities asPSUs) while computing statistical tests, using the survey functions of STATA 12 SE Version.

To assess the determinants of clients’ satisfaction, the chi-square test was used for bivariate analysis and multivariate probit model was used to assess the net effect of explanatory variables on outcome variable. Findings are reported as significant where the p-value is <0.05 (significant at the 5% level).

Results

More than two-thirds of the respondents were 20–29 years old (67%) and more than one-third were Brahmins/Chhetris (37%). Respondents with secondary education represented nearly half (46%) of the sample. It took less than 30 min for just over one-third of the respondents (37%) to reach to the health facility and most (82%) waited for less than 30 min before seeing a provider after reaching the facility. Half of the respondents perceived that the maternity department was overcrowded and more than four-fifths of mothers (83%) were breastfed within an hour. Almost two-thirds (65%) had paid for the service sought in the health facility. Half of the mothers were advised on the danger signs of mothers and newborns and less than two-thirds of mothers (61%) were advised on exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months (Table 1).

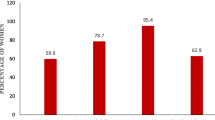

The mean satisfaction score and proportion of clients satisfied with maternity care is presented in Table 1. Satisfaction was highest among Brahmins/Chhetris compared to other caste/ethnic groups, and lowest among Muslims (Table 1). More than two-thirds of clients (69%) from the hill region and more than four-fifths (81%) from rural areas were satisfied, while only one-third of clients (33%) from urban areas and the terai were satisfied with the maternity care received. Clients who waited for less than 30 min before seeing a provider had higher satisfaction (54%) than those who had to wait for longer than 60 min (9%). Clients who reached the facilities within 30 min had higher satisfaction compared to those who travelled for more than 30 min. Clients who did not pay for the service and who did not report overcrowding at the health facility had higher satisfaction.

Overcrowding was more commonly reported at higher level hospitals (68%) than PHCCs and HPs/SHPs (2% and 0% respectively). It was also more common in urban (64%) compared to rural (14%) areas and in the terai districts (60%) compared to the mountain districts (4%). Furthermore, clients were more likely to have to pay for services at higher level hospitals and district hospitals (62% and 84% respectively) compared to HPs/SHPs (17%). A higher proportion of hospital deliveries was observed among Newars (98%) compared to other caste/ethnic groups, and the lowest proportion was observed among Muslims (68%) (data not shown).

Clients who received advice from health workers on danger signs for mothers and exclusive breastfeeding also had higher satisfaction. Clients who had an opportunity to ask questions to the health providers had higher satisfaction compared with those did not have that opportunity (Table 1).

Hence, bivariate analysis showed association of range of factors such as caste/ethnicity, ecological zone, place of residence (rural/urban), time taken to reach health facility, waiting time at health facility, overcrowding at health facility, payment for services, interpersonal communication skills of service provider and receipt of key informations (danger signs, new born care, exclusive breastfeeding) and structural factor (availability of drinking water) with maternity client satisfaction. However, multivariate analysis showed that those who had longer waiting times, i.e. at least 60 min, (satisfaction coefficient = −1.14, 95% CI (−1.77- -0.50) or between 30 and 59 min (coefficient = −1.00 95% CI (−1.61- -0.39)) and those who perceived the facility to be overcrowded (coefficient = −0.53,95% CI(−0.79- -0.28)) were more likely to be dissatisfied (Table 2). Residing in hill districts and rural areas, and having an opportunity to ask questions and breastfeeding within an hour of birth were positively associated with client satisfaction.

Discussion

Client satisfaction with health care has been argued as a subjective as well as dynamic perception of the extent to which expected health care is received [7, 26, 27]. This study aimed to measure the determinants of client satisfaction. Specifically, the attribution of client characteristics, demand-side and supply-side factors on client satisfaction were investigated. The findings from the current study revealed that women wanted prompt attention without overcrowding. In addition, allowing mothers to ask questions was significantly associated with satisfaction with maternity care.

Factors such as ecological zone and place of residence were significantly associated with client satisfaction. Clients from rural areas were more satisfied with the care provided at the facility compared with clients from urban areas. Higher satisfaction among rural clients can be partly attributed to their lower educational and empowerment level and lower socio-economic class compared to urban counterparts. Women from rural areas might be less empowered to compare and express satisfaction compared with those from urban areas. Literature suggests that economically middle-class women prefer personal choice and less professional dominance during childbirth in comparison to lower-class women [28, 29]. Furthermore, Nepal’s health care delivery system is a mix of private and public health institutions. While there is a better choice in urban areas, only public health facilities are available in rural areas. Women from urban areas may be more familiar with the care provided by private health facilities. Literature suggests prior exposure and information from friends/relatives to be a determinant of women’s perception of maternity care [30].

Clients who were given enough time and attention to ask questions to better understand their care and their health status were more likely to be satisfied. Being able to address any concerns will give clients more confidence in the services provided, resulting in increased satisfaction. A study conducted in Sri Lanka found that clients who were provided with adequate information regarding newborn care, breastfeeding and others after examinations were found to be more satisfied [15] and another systematic review showed a strong correlation between satisfaction and education/information given [31].

This study revealed that longer waiting times increased the likelihood of dissatisfaction among clients, which is consistent with the findings of a study conducted in Bangladesh [2]. Prompt attention after reaching a facility has been found to be significantly associated with client satisfaction [32]. This may be due to higher opportunity costs associated with the visit, i.e. this time could be used for other income generating activities by family members. In addition, overcrowding at the facility is negatively associated with client satisfaction. This finding is consistent with other studies [33]. Overcrowding might affect numerous indicators of satisfaction and quality of care, including lead to longer waiting times, less time with providers, lack of bed space, and early discharge. A previous study from Nepal reported overcrowding, mainly at the higher level health facilities [34]. The findings suggest to a need for renewed focus on strengthening lower level maternity facilities and building the capacity of peripheral health workers to develop trust on them. Furthermore, a strong referral network need to be made functional with a provision of free transportation from a birthing centre to referral hospital [34].

Current study showed that Brahmin/Chettri clients had the highest satisfaction and Muslims the lowest. It is not clear whether this independent association reflects differences in clients’ expectations or reflects actual differences they had with the quality of care. Differences in client satisfaction by ethnicity have been noted in other settings as well [35].

The mean satisfaction score was higher for lower level facilities (PHCCs or below) than higher level facilities (district hospitals or above). However, the likelihood of satisfaction was not significantly different by level of health facility in the multivariate analysis. Previous studies have been inconsistent, with some showing clients attending higher level facilities to be more satisfied than those attending community level facilities [36], and others reporting clients were more satisfied with the lower level health facilities [15, 37, 38].

Client’s age did not have any significant association with client satisfaction, which is in contrast to another study which showed that age has a statistically significant effect on client satisfaction [14]. Older clients were more likely to be satisfied as demonstrated by studies conducted in Riyadh [17], northeast France [13] and the United States [12, 14] while some other studies have reported that age has a minor influence on client satisfaction [16, 39]. One of the explanations for age not being associated with satisfaction here could be a narrow age range of maternity clients which might have shaped similar expectations.

In contrast to the findings from studies conducted in Riyadh [17] and Kuwait [40] showing higher educational status of clients to be positively associated satisfaction. Studies conducted in South Africa [41] and India [36] showed greater dissatisfaction among higher educated parents. Similar to this study, a South African study found that satisfaction level did not vary much with clients’ socio-demographic characteristics [41].

Although the extent of disrespect and abuse in health facilities has not been systematically documented or well-defined in Nepal, a qualitative study revealed that disrespect and abuse in childbirth represents an important barrier to utilization of skilled birth care and other health care at health facilities [42]. In line with a this study [42], our study also reported significantly lower satisfaction among those who were scolded at facilities by the health providers. This finding suggests communication skills and behaviour improvement should be integrated with other health related trainings. This study revealed that payment to the services was not linked to client satisfaction; the perceived competence, assurance of treatment irrespective of ability to pay were the determining factors to trust in health care, may lead to higher satisfactions [11].

The findings are prone to some limitations. Since only a small number of respondents could be interviewed from Health posts and Sub health posts (5% of total respondents), due to low caseload, the findings may be more relevant to hospitals in Nepal. Since client satisfaction has been measured from client exit interviews, satisfaction is likely to have been over reported compared to data collection at the community level. It is debatable whether clients’ reporting of satisfaction truly reflects the quality of care received [26]. Previous studies highlight the gap between clients’ perception of high quality care and that perceived by health care professionals [2]. Client satisfaction was measured against the environment, however, studies have shown that satisfaction with self/personal control is also an important element of maternity client satisfaction [1]. Exit interview survey clients have some level of satisfaction with that particular facility and have made a choice to come there. This method of data collection may miss the views of those who are actually dissatisfied with that facility and have gone elsewhere. Likewise, providers may also perform better when they are aware that they are being observed or their clients are being interviewed. We assessed maternity client satisfaction based on background characteristics of clients and client perception to selected supply-side factors. However, there are other potential factors that may affect client satisfaction such as internal factors [43] and supply-side factors such as availability of drugs, mode of delivery, length of stay in health facility,contact-time with service providers, and others [22]. In addition, the primary aim of the STS survey was to compare service provision, distribution and client satisfaction across types of public health facilities and to assess progress over survey years rather than studying determinants of client satisfaction.

Conclusions

This study did not find any differences in clients’ satisfaction with socio-demographic characteristics aside from caste/ethnicity. However, key supply side factors, such as longer waiting times and overcrowding at facility, were associated with poor client satisfaction, whereas getting an opportunity to ask questions was positively associated with client satisfaction, suggesting the quality at the point-of-care will be instrumental in order to enhance client satisfaction.

Abbreviations

- CSPro:

-

Census and Survey Processing System

- EPSEM:

-

Equal Probability Sampling Method

- HP:

-

Health Post

- MOHP:

-

Ministry of Health and Population

- NHSP:

-

Nepal Health Sector Program

- NHSSP:

-

Nepal Health Sector Support Program

- PCA:

-

Principle Component Analysis

- PHCC:

-

Primary Health Care Centre

- PSU:

-

Primary Sampling Unit

- SHP:

-

Sub-Health Post

- STS:

-

Service Tracking Survey

References

Goodman P, Mackey MC, Tavakoli AS. Factors related to childbirth satisfaction. J Adv Nurs. 2004;46(2):212–9.

Aldana JM, Piechulek H, Al-Sabir A. Client satisfaction and quality of health care in rural Bangladesh. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79(6):512–7.

Agha S, Karim AM, Balal A, Sosler S. The impact of a reproductive health franchise on client satisfaction in rural Nepal. Health Policy Plan. 2007;22(5):320–8.

Gadallah MA, Allam MF, Ahmed AM, E-S EM. Are patients and healthcare providers satisfied with health sector reform implemented in family health centres? QualSaf Health Care. 2010;19(6):e4.

Ronsmans C, Etard JF, Walraven G, Hoj L, Dumont A, de Bernis L, Kodio B. Maternal mortality and access to obstetric services in West Africa. Tropical Med Int Health. 2003;8(10):940–8.

Fernando D, Jayatilleka A, Karunaratna V. Pregnancy--reducing maternal deaths and disability in Sri Lanka: national strategies. Br Med Bull. 2003;67:85–98.

Jahn A, Dar Iang M, Shah U, Diesfeld HJ. Maternity care in rural Nepal: a health service analysis. Tropical Med Int Health. 2000;5(9):657–65.

MOHP. National Health Policy 1991. In. Ministry of Health: Kathmandu; 1991.

MOHP. Nepal Health Sector Programme- Implementation Plan 2010–2015. In. Ministry of Health and Population: Kathmandu; 2010.

Ministry of Health and Population. National Health Policy. Kathmandu: Ministry of Health and Population; 2071. p. 2014.

Gopichandran V, Chetlapalli SK. Dimensions and determinants of trust in health care in resource poor settings--a qualitative exploration. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e69170.

Hall JA, Dornan MC. Patient sociodemographic characteristics as predictors of satisfaction with medical care: a meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 1990;30(7):811–8.

Nguyen Thi PL, Briancon S, Empereur F, Guillemin F. Factors determining inpatient satisfaction with care. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54(4):493–504.

Young GJ, Meterko M, Desai KR. Patient satisfaction with hospital care: effects of demographic and institutional characteristics. Med Care. 2000;38(3):325–34.

Senarath U, Fernando DN, Rodrigo I. Factors determining client satisfaction with hospital-based perinatal care in Sri Lanka. Tropical Med Int Health. 2006;11(9):1442–51.

Schoenfelder T, Schaal T, Klewer J, Kugler J. Patient satisfaction and willingness to return to the provider among women undergoing gynecological surgery. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;2014:1–8.

Saeed AA, Mohammed BA, Magzoub ME, Al-Doghaither AH. Satisfaction and correlates of patients' satisfaction with physicians' services in primary health care centers. Saudi Med J. 2001;22(3):262–7.

Mehata S, Lekhak SC, Chand PB, Singh DR, Poudel P, Barnett S. Service Tracking Survery. Kathmandu: Ministry of Health and Population (MOHP),Government of Nepal; 2013.

Ministry of Health and Population (MOHP) [Nepal] HRaSDFH, and Nepal Health Sector Support Programme (NHSSP): Service Tracking Survey 2013; 2014.

MOHP, HERD, NHSSP. Service Tracking Survery 2013. Kathmandu: Ministry of Health and Population (MOHP), Health Research and Social Development Forum (HERD), Nepal Health Sector Support Programme (NHSSP); 2014.

Likert RA. Technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology. 1932;140:5–53.

Hulton AL, Mathews Z, Stones RW. A framework for the evaluation of quality of care in maternity services. Southampton: University of Southampton; 2000.

Subedi BK, Chand PB, Marasini BR, Tiwari S, Poudel P, Mehata S, Pradhan A, Acharya LB, Lievens T, Hepworth S, et al. Service Tracking Survey 2011. In. Ministry of Health and Population: Kathmandu; 2012.

Filmer D, Pritchett LH. Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data--or tears: an application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography. 2001;38(1):115–32.

Regua SES. Formulation of index for student satisfaction in the university of philippines. LOS BAÑOS: University of Philippines. https://www.academia.edu/6348908/FORMULATION_OF_AN_INDEX_FOR_STUDENT_SATISFACTION_IN_THE_UNIVERSITY_OF_THE_PHILIPPINES_LOS_BA%C3%91OS.

Nabbuye-Sekandi J, Makumbi FE, Kasangaki A, Kizza IB, Tugumisirize J, Nshimye E, Mbabali S, Peters DH. Patient satisfaction with services in outpatient clinics at Mulago hospital, Uganda. Int J Qual Health Care. 2011;23(5):516–23.

Larrabee JH, Bolden LV. Defining patient-perceived quality of nursing care. J Nurs Care Qual. 2001;16(1):34–60. quiz 74-35

Lazarus ES. What do women want?: Issues of choice, control, and class in pregnancy and childbirth. Med Anthropol Q. 1994;8(1):25–46.

Kabakian-Khasholian T, Campbell O, Shediac-Rizkallah M, Ghorayeb F. Women's experiences of maternity care: satisfaction or passivity? Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(1):103–13.

Paudel YR, Mehata S, Paudel D, Dariang M, Aryal KK, Poudel P, King S, Barnett S. Women's Satisfaction of Maternity Care in Nepal and Its Correlation with Intended Future Utilization. Int J Reprod Med. 2015;2015:783050.

Espinel AG, Shah RK, McCormick ME, Krakovitz PR, Boss EF. Patient satisfaction in pediatric surgical care: a systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;150(5):739–49.

Bleich SN, Özaltin E, Murray CJ. How does satisfaction with the health-care system relate to patient experience? Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87(4):271–8.

Hutchinson PL, Do M, Agha S. Measuring client satisfaction and the quality of family planning services: a comparative analysis of public and private health facilities in Tanzania, Kenya and Ghana. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:203.

FHD/NHSSP. Responding to Increased Demand for Institutional Childbirths at Referral Hospitals in Nepal: Situational Analysis and Emerging Options. Kathmandu: FHD/NHSSP; 2013.

Sitzia J, Wood N. Patient satisfaction: a review of issues and concepts. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45(12):1829–43.

Goel S, Sharma D, Bahuguna P, Raj S, Singh A. Predictors of Patient Satisfaction in Three Tiers of Health Care Facilities of North India. J Community Med Health Educ S. 2014;2:2161–0711.

Janssen PA, Klein MC, Harris SJ, Soolsma J, Seymour LC. Single room maternity care and client satisfaction. Birth. 2000;27(4):235–43.

Karkee R, Lee AH, Pokharel PK. Women's perception of quality of maternity services: a longitudinal survey in Nepal. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:45.

Jenkinson C, Coulter A, Bruster S, Richards N, Chandola T. Patients’ experiences and satisfaction with health care: results of a questionnaire study of specific aspects of care. Quality and safety in health care. 2002;11(4):335–9.

Alotaibi M, Alazemi T, Alazemi F, Bakir Y. Patient satisfaction with primary health-care services in Kuwait. Int J Nurs Pract. 2015;21(3):249–57.

Chimbindi N, Bärnighausen T, Newell M-L. Patient satisfaction with HIV and TB treatment in a public programme in rural KwaZulu-Natal: evidence from patient-exit interviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):32.

O'Donnell E, Utz B, Khonje D, van den Broek N. 'At the right time, in the right way, with the right resources': perceptions of the quality of care provided during childbirth in Malawi. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:248.

Green JM, Baston HA. Feeling in control during labor: concepts, correlates, and consequences. Birth. 2003;30(4):235–47.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support from MoHP and all the advisors of Nepal Health Sector Support Programme and Options Limited, UK, for their encouragement while preparing the paper. Also, authors would like to thanks to Dr. Deepak Paudel for his support for manuscript review.

Funding

The service Tracking Survey was funded by UK Department for International Development (DFID).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SB, MD, YP, KKA and SM had the concept of the paper. YP, SP, RM and SM conducted literature review, carried out the data analysis, and prepared the first draft. SK, SB, MD and KKA suggested on the methodology and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and agreed on the final version of paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for the survey was sought from the Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC) and formal approval from the selected districts and facilities was requested with an authorized letter from the ministry of health and population (MoHP). Formal approval for data collection was received from MoHP and each District Health Office (DHO). Ethics committee approved the use of verbal consent obtained from the participants. Before interviewing, all respondents were briefed on the purpose of the survey and were shown an approval letter from the MoHP and DHO. They were assured about the confidentiality of the information collected and their right to refuse to participate or withdraw at any time during the interview. Verbal consent was received from all participants before the interview took place.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Mehata, S., Paudel, Y.R., Dariang, M. et al. Factors determining satisfaction among facility-based maternity clients in Nepal. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 17, 319 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1532-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1532-0