Abstract

Background

Small-for-gestational-age in infancy is a known risk factor not only for short-term prognosis but also for several long-term outcomes, such as neurological and metabolic disorders in adulthood. Previous research has shown that severe nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy (NVP) and hyperemesis gravidarum, which is an extreme form of NVP, represent risk factors for small-for-gestational-age birth. However, there is no clear consensus on this association. Thus, in the present study, we investigated the correlation between hyperemesis gravidarum and NVP on the one hand, and infant birth weight on the other, using data from the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS).

Methods

The data utilized in the present study were obtained from the JECS, an ongoing cohort study that began in January 2011. Our sample size was 8635 parent–child pairs. The presence or absence of severe NVP, hyperemesis gravidarum, and potential confounding factors were noted. A multivariable regression analysis was used to estimate risks for small-for-gestational-age birth, and the results were expressed as risk ratios and 95 % confidence intervals.

Results

The risk ratios of small-for-gestational-age birth (95 % confidence interval) for mothers with severe NVP and those with hyperemesis gravidarum were 0.86 (0.62–1.19) and 0.81 (0.39–1.66), respectively, which represents a non-significant result.

Conclusions

In our analysis of JECS data, neither severe NVP nor hyperemesis gravidarum was associated with increased risk for small-for-gestational-age birth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

There is a high incidence of nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy (NVP), reported at 35–91 % [1–4]. NVP can become severe in 0.3–3.6 % of cases, with hyperemesis gravidarum (HG) as an extreme form of NVP that is associated with weight loss [1–4]. The incidence of HG varies by country, and was reported at nearly 3.6 % in Japan [4].

The condition known as small-for-gestational-age (SGA) is a concern in infants, as it carries with it a multitude of risks, including a poorer life prognosis, neurological disorders, and metabolic diseases during adulthood [5, 6]. SGA is defined using the 10th percentile for birth weight as the cutoff value [7, 8].

There are many risk factors for SGA, but most of these are not well understood. Extreme NVP may result in poor health during pregnancy, which can influence the prognosis of fetuses [9, 10], possibly leading to an increase in the risk of SGA birth [9, 11–13].

Recent systematic reviews suggest that HG increases the risk of low birth weight and SGA by 42 and 28 %, respectively [12]. Furthermore, severe maternal weight loss in early pregnancy, typically linked with extreme NVP, has been linked with growth restriction [9]. However, other reports have suggested that HG does not influence growth restriction [14, 15], birth weight [11, 16, 17], or risk for SGA [18]. Thus, there is as yet no clear consensus on this issue [11, 16, 17].

In the present study, we investigated the effect of severe NVP and HG (extreme NVP), with respect to the risk for SGA birth in the Japanese population.

Methods

The data used in this study were obtained from The Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS), which is an ongoing cohort study that began in January 2011. The objective of the JECS is to determine the effect of environmental factors on children’s health.

More than 100,000 pregnant women were recruited over a period of approximately 3 years. The recruitment period ended in March 2014.

The pregnant women lived in one of the 15 study regions included in the JECS. The 15 regions were selected to cover wide geographical areas in Japan. We made contact with as many of these expecting mothers as possible. Either or both of the following two recruitment protocols were applied: 1) recruitment at the time of the first prenatal examination at cooperating health care providers, i.e., obstetric facilities (provider-mediated community-based recruitment), and/or 2) recruitment at local government offices issuing pregnancy journals, namely the Mother-Child Health Handbook, which is an official complimentary booklet that all expecting mothers in Japan are given when they become pregnant in order to receive municipal services for pregnancy, delivery, and childcare.

The JECS protocol was approved by the Review Board on epidemiological studies of the Ministry of the Environment, and by the Ethics Committees of all participating institutions. The JECS is conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and other nationally valid regulations, and with written informed consent from all participants. However, those who had difficulty filling out the questionnaire in Japanese or had other unavoidable circumstances preventing them from participating in the survey, such as being in their hometown at the time of childbirth, were excluded from the analysis [19, 20].

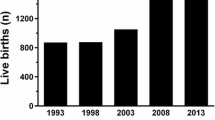

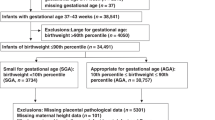

As of the end of 2011, a total of 9646 participants had successful childbirths. After excluding cases with missing data and preterm births, we analyzed the records of the remaining 8631 women who had single, full-term (37–42 weeks) pregnancies (Fig. 1). The present study is based on the data set “jecs-ag-ai-20131008”, which was released in October 2013.

Follow-up was conducted using a self-administered questionnaire. The questionnaires were completed during the first and second trimesters, as well as at 1 month postpartum. We obtained medical information from medical records transferred for examinations during the same time periods.

The questionnaires were designed to collect information on pregnancy and medical history as well as on confounding and modifying factors, such as social and lifestyle factors. We collected information on birth, such as the birth weight, from the transferred medical records.

The following question was included in the questionnaire for the second trimester to determine the status of HG: “Did you have morning sickness from conception until about week 12 of the pregnancy?” (1 = no, 2 = just nausea, 3 = vomiting, but was able to eat, 4 = vomiting, and was unable to eat). We thus defined the following groups for analysis: the “food intake group”, which included the women who answered 1, 2, or 3; the “no food” or severe NVP group, which included the women who answered 4; and the HG group, which was a subset of participants from the NVP group that included women with severe NVP and weight loss of >5 % from pre-pregnant weight in the first trimester.

The participants underwent ultrasound examinations during the first trimester, and these results were used to determine the expected date of delivery if there was more than a 7-day difference between this date and the date calculated from the last menstrual period. Birth weight was transferred from medical records, and SGA was concluded if the weight was below the 10th percentile according to primiparous and multiparous birth size standards for both genders by gestational age in Japanese neonates [21].

The following covariates were included in the questionnaire for the first trimester: maternal age, pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI), parity, smoking status, and alcohol consumption; the covariates of education and income were included in the questionnaire for the second trimester; the covariates of weight gain during pregnancy were calculated based on information from medical records.

Statistical analysis

Based on the records of mothers of singletons delivered at full term, we evaluated the relationship between SGA and NVP, HG, factors related to the patient’s background, and social factors. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). We calculated crude relative risk ratios (RRs) and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) using the chi-squared test. The interrelationship between patient background, social factors, and birth weight was evaluated by univariate analysis. Covariates of maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, weight gain during pregnancy, gestational age at birth, smoking, alcohol consumption, education, and income were included in the calculation of adjusted risk ratios. The adjusted relative RR was calculated using a log-binomial regression model. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

There were 880 patients (10.2 %) who experienced severe NVP, and 136 patients (1.6 %) who experienced HG. The mean age of participants, weeks of pregnancy at birth, and birth weight were 30.6 ± 5.02 years, 39.0 ± 1.14 weeks, and 3050.0 ± 371.32 g, respectively. The results of the univariate analysis are shown in Table 1. The adjusted risk ratios for mothers with a pre-pregnancy BMI of <18.5 kg/m2, mothers with a weight gain of <7 kg during pregnancy, and those who smoked were 1.58 (95 % CI, 1.32–1.90), 1.28 (95 % CI, 1.05–1.55), and 1.48 (95 % CI, 1.11–1.97), respectively, indicating a slightly higher risk of SGA birth. Moreover, the risk ratio was 0.60 (95 % CI, 0.43–0.85) for mothers with a pre-pregnancy BMI of >25 kg/m2, and 0.52 (95 % CI, 0.41–0.66) for mothers with a weight gain of >12 kg during pregnancy, indicating a lower risk of SGA birth.

Tables 2 and 3 show the crude and adjusted risk ratios calculated using covariates such as the mother’s age, pre-pregnancy BMI, weight gain during pregnancy, parity, smoking and drinking, education, and income, to determine the effect of severe NVP or HG on the risk of SGA. The risk ratios for mothers with severe NVP and those with HG were 0.86 (95 % CI, 0.62–1.19) and 0.81 (95 % CI, 0.39–1.66), respectively, indicating a non-significant effect of NVP or HG on the risk for SGA birth.

Discussion

In our analysis of JECS data, neither NVP nor HG was associated with the risk for SGA birth. The incidence of HG was 1.6 %, which is lower than the 3.6 % incidence reported by the latest study in the general Japanese population [4], but within the range of 0.3–2.0 % reported by other studies [1–3]. In addition, the participants in our study reported an incidence of NVP of 10.2 %, which is lower than the 33 % incidence reported by Chortatos et al. [22]; the difference is likely related to the fact that we defined NVP based on self-reported accounts of reduced food intake.

Our study has a methodological limitation, because data regarding the severity of NVP were collected via a self-response questionnaire, while data regarding maternal weight loss were collected from the Mother-Child Health Handbooks and hospital records, and it is unknown whether participants required hospitalization for severe HG, how long severe NVP or HG persisted, and whether the condition reflected in the biochemical parameters.

Another limitation is the fact that the questionnaire was applied in the second trimester, but the questions themselves referred to early pregnancy; thus, there might be the risk of recall bias, resulting in an overestimation of the severity of NVP. However, we do not believe that this effect was significant, because the questionnaire was applied during the pregnancy period; moreover, the definition of HG was based on independent records of maternal weight loss.

A further limitation is related to the fact that our results were obtained based on the data regarding 136 cases of HG, which may be considered a small number in the context of an epidemiologic study. Nonetheless, given that the incidence of HG is expected to be under 2 %, and there is yet no consensus regarding the influence of HG on the risk for SGA birth, we believe that a sample size of 136 cases can ensure sufficient power to detect relevant trends, as some reports indicate that HG may increase the risk for SGA birth by up to 40 %; moreover, even if the power is low, the potential tendencies should be recognizable, because the confidence interval for our results is narrow.

Finally, another limitation of the study is related to the fact that the incidence of SGA birth in the group of mothers for whom weight gain information was missing was relatively high. Unfortunately, the reason for this higher incidence of SGA births cannot be assessed based on the data available to us. While it is possible that the characteristics of the mothers excluded from the study because of missing information on weight gain may have an influence on the results, we do not expect this influence to extend to the conclusions of our study.

Previous research demonstrating HG as a risk factor for SGA includes a study by Bailit et al., which showed that neonates born from mothers requiring hospitalization for HG were 125 g smaller compared to those born from mothers without such symptoms [11]. However, that study employed hospital admission rates for defining HG, which is a more subjective measure than is maternal weight loss. On the other hand, in other studies, which reported that HG leads to SGA birth [9, 10], the HG definition was based on maternal weight loss throughout pregnancy period; however, it was unclear whether the weight change was due to HG. In our study, the HG group included mothers with severe NVP (vomiting and not able to eat) and with weight loss of >5 % from pre-pregnant weight in the first trimester. Based on such a strict definition, our results showed that neither severe nor extreme NVP (i.e., HG) represented a risk factor for SGA birth.

The recent Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study reported that HG-exposed babies had slightly reduced birthweight, but there were no association between HG and SGA birth [18, 23], although it should be noted that no adjustment for weight gain was made, while adjusting for smoking status slightly increased the effect of HG. Further reports have suggested that HG does not influence birth weight [11, 16, 17]. Our results are in agreement with the findings of the studies that reported no relationship between HG and SGA birth; nevertheless, the relevance of adjusting for weight gain when evaluating the influence of HG should be noted, implying that the risk for SGA birth is reduced when sufficient weight gain is ensured during pregnancy.

It is important to note that both sets of studies (i.e., those concluding an effect and those concluding a lack of an effect) studied patients who required hospitalization. Even under these conditions, there is no conclusive evidence regarding the effect of HG on birth weight. Therefore, precise diagnostic criteria for HG should be developed for use in future investigations.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that neither NVP nor HG affect birth weight. Despite the methodological limitations of the study, we believe that these results indicate that pregnant women need not be concerned about potential risk for SGA birth due to NVP or HG.

Abbreviations

- 95 % CI:

-

95 % confidence interval

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- HG:

-

Hyperemesis gravidarum

- JECS:

-

Japan Environment and Children’s Study

- NVP:

-

Nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy

- RR:

-

Risk ratio

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SGA:

-

Small-for-gestational-age

References

Einarson TR, Piwko C, Koren G. Quantifying the global rates of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: a meta analysis. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol. 2013;20:e171–83.

Källén B. Hyperemesis during pregnancy and delivery outcome: a registry study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1987;26:291–302.

Einarson TR, Piwko C, Koren G. Prevalence of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy in the USA: a meta analysis. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol. 2013;20:e163–70.

Matsuo K, Ushioda N, Nagamatsu M, Kimura T. Hyperemesis gravidarum in Eastern Asian population. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2007;64:213–6.

Kok JH, den Ouden AL, Verloove-Vanhorick SP, Brand R. Outcome of very preterm small for gestational age infants: The first nine years of life. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:162–8.

Patterson RM, Prihoda TJ, Gibbs CE, Wood RC. Analysis of birth weight percentile as a predictor of perinatal outcome. Obstetrics Gynecol. 1986;68:459–63.

Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Washington, DC 20090-6920, USA. Intrauterine growth restriction. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2001;72:85–96.

Goldenberg RL, Cutter GR, Hoffman HJ, Foster JM, Nelson KG, Hauth JC. Intrauterine growth retardation: Standards for diagnosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161:271–7.

Dodds L, Fell DB, Joseph KS, Allen VM, Butler B. Outcomes of pregnancies complicated by hyperemesis gravidarum. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(2 Pt 1):285–92.

Gross S, Librach C, Cecutti A. Maternal weight loss associated with hyperemesis gravidarum:a predictor of fetal outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160:906–9.

Bailit JL. Hyperemesis gravidarium: epidemiologic findings from a large cohort. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(3 Pt 1):811–4.

Veenendaal MV, van Abeelen AF, Painter RC, van der Post JA, Roseboom TJ. Consequences of hyperemesis gravidarum for offspring: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2011;118:1302–13.

Zhou Q, O’Brien B, Relyea J. Severity of nausea and vomiting during pregnancy: what does it predict? Birth. 1999;26:108–14.

Bashiri A, Neumann L, Maymon E, Katz M. Hyperemesis gravidarum: epidemiologic features, complications and outcome. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1995;63:135–8.

Hallak M, Tsalamandris K, Dombrowski MP, Isada NB, Pryde PG, Evans MI. Hyperemesis gravidarum. Effects on fetal outcome. J Reprod Med. 1996;41:871–4.

Tan PC, Jacob R, Quek KF, Omar SZ. Pregnancy outcome in hyperemesis gravidarum and the effect of laboratory clinical indicators of hyperemesis severity. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2007;33:457–64.

Tsang IS, Katz VL, Wells SD. Maternal and fetal outcomes in hyperemesis gravidarum. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1996;55:231–5.

Vandraas K, Vikanes A, Vangen S, Magnus P, Stoer N, Grjibovski A. Hyperemesis gravidarum and birth outcomes-a population-based cohort study of 2.2 million births in the Norwegian Birth Registry. BJOG. 2013;13:1654–60.

Kawamoto T, Nitta H, Murata K, Toda E, Tsukamoto N, Hasegawa M, et al. Rationale and study design of the Japan environment and children’s study (JECS). BMC Public Health. 2014;14:25.

Ministry of the Environment. Japan Environment and Children Study. [homepage on the Internet] http://www.env.go.jp/en/chemi/hs/jecs/ [updated 9 Sep 2013; Accessed 22 Sept 2013].

Itabashi K, Miura F, Uehara R, Nakamura Y. New Japanese neonatal anthropometric charts for gestational age at birth. Pediatr Int. 2014;56:702–8.

Chortatos A, Haugen M, Iversen PO, Vikanes Å, Eberhard-Gran M, Bjelland EK, Magnus P, Veierød MB. Pregnancy complications and birth outcomes among women experiencing nausea only or nausea and vomiting during pregnancy in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:138.

Vikanes ÅV, Støer NC, Magnus P, Grjibovski AM. Hyperemesis gravidarum and pregnancy outcomes in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort - a cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:169.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to all participants of this study, and all individuals involved in data collection. Members of JECS as of 2015 (principal investigator, Toshihiro Kawamoto): Hirohisa Saito (National Center for Child Health and Development, Tokyo, Japan), Reiko Kishi (Hokkaido University, Sapporo, Japan), Nobuo Yaegashi (Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan), Koichi Hashimoto (Fukushima Medical University, Fukushima, Japan), Chisato Mori (Chiba University, Chiba, Japan), Fumiki Hirahara (Yokohama City University, Yokohama, Japan), Zentaro Yamagata (University of Yamanashi, Chuo, Japan), Hidekuni Inadera (University of Toyama, Toyama, Japan), Michihiro Kamijima (Nagoya City University, Nagoya, Japan), Ikuo Konishi (Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan), Hiroyasu Iso (Osaka University, Suita, Japan), Masayuki Shima (Hyogo College of Medicine, Nishinomiya, Japan), Toshihide Ogawa (Tottori University, Yonago, Japan), Narufumi Suganuma (Kochi University, Nankoku, Japan), Koichi Kusuhara (University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Kitakyushu, Japan), Takahiko Katoh (Kumamoto University, Kumamoto, Japan).

Funding

JECS was funded by the Japanese Ministry of the Environment. The findings and conclusions of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the above government. This article was supported in part by MEXT KAKENHI (24119004) at the time of the design and composition. The funding bodies had no role in the design of the study, collection and analysis of data, interpretation of the results, writing the manuscript, or decision to publish.

Availability of data and materials

The data used to derive our conclusions are unsuitable for public deposition due to ethical restrictions and specific legal framework in Japan. It is prohibited by the Act on the Protection of Personal Information (Act No. 57 of 30 May 2003, amended on 9 September 2015) to publicly deposit data containing personal information. The Ethical Guidelines for Epidemiological Research enforced by the Japan Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology and the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare also restricts the open sharing of the epidemiologic data. All inquiries about access to data should be sent to jecs-en@nies.go.jp. The person responsible for handling inquiries sent to this e-mail address is Dr Shoji F. Nakayama, JECS Programme Office, National Institute for Environmental Studies.

Authors’ contributions

K Kusuhara, K Kato, TK, and SM designed the study. MS, MT, and SM analyzed and interpreted the data. SM, MS, ES, and AS wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed critical revisions to the manuscript, and read and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The JECS protocol was approved by the Review Board on epidemiological studies of the Ministry of the Environment, and by the Ethics Committees of all participating institutions. The JECS is conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and other nationally valid regulations, and with written informed consent from all participants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Morokuma, S., Shimokawa, M., Kato, K. et al. Relationship between hyperemesis gravidarum and small-for-gestational-age in the Japanese population: the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS). BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 16, 247 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-1041-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-1041-6