Abstract

Background

Numerous health benefits are associated with achieving optimal diet and physical activity behaviours during and after pregnancy. Understanding predictors of these behaviours is an important public health consideration, yet little is known regarding associations between clinician advice and diet and physical activity behaviours in postpartum women. The aims of this study were to compare the frequency of dietary and physical activity advice provided by clinicians during and after pregnancy and assess if this advice is associated with postpartum diet and physical activity behaviours.

Methods

First time mothers (n = 448) enrolled in the Melbourne InFANT Extend trial completed the Cancer Council of Australia’s Food Frequency Questionnaire when they were three to four months postpartum, which assessed usual fruit and vegetable intake (serves/day). Total physical activity time, time spent walking and time in both moderate and vigorous activity for the previous week (min/week) were assessed using the Active Australia Survey. Advice received during and following pregnancy were assessed by separate survey items, which asked whether a healthcare practitioner had discussed eating a healthy diet and being physically active. Linear and logistic regression assessed associations of advice with dietary intake and physical activity.

Results

In total, 8.6 % of women met guidelines for combined fruit and vegetable intake. Overall, mean total physical activity time was 350.9 ± 281.1 min/week. Time spent walking (251.97 ± 196.78 min/week), was greater than time spent in moderate (36.68 ± 88.58 min/week) or vigorous activity (61.74 ± 109.96 min/week) and 63.2 % of women were meeting physical activity recommendations. The majority of women reported they received advice regarding healthy eating (87.1 %) and physical activity (82.8 %) during pregnancy. Fewer women reported receiving healthy eating (47.5 %) and physical activity (51.9 %) advice by three months postpartum. There was no significant association found between provision of dietary and/or physical activity advice, and mother’s dietary intakes or physical activity levels.

Conclusions

Healthy diet and physical activity advice was received less after pregnancy than during pregnancy yet no association between receipt of advice and behaviour was observed. More intensive approaches than provision of advice may be required to promote healthy diet and physical activity behaviours in new mothers.

Trial registration

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12611000386932 13/04/2011)

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Much evidence exists supporting the health benefits for women in achieving healthy lifestyle behaviours both during [1–5] and following [6–8] pregnancy. Adopting healthy dietary and physical activity behaviours during the postpartum period is particularly important to promote optimal maternal health, both in the short and long term. A diet adequate in fruit and vegetables and low in fat has been shown to play a vital role in reducing the risk for many diseases [8, 9] and research has linked poor dietary habits with the development of non–communicable diseases including type 2 diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease and some cancers [10, 11]. Specifically following childbirth, healthy eating is important to adequately support breastfeeding [12] and demonstrate healthy role modelling behaviours for infants [12]. However it is commonplace for women of all ages not to meet dietary intake recommendations [13]. Although some women may eat healthily during pregnancy [14] these habits often discontinue following childbirth [14, 15] with declines in adequacy of fruit and vegetable intake having been observed [16–18].

Regular physical activity during the postpartum period has been associated with improved mental health [6, 7] as well as improved cholesterol levels and insulin sensitivity [6, 19], and increased chance of women returning to pre-pregnancy weight [6, 20, 21]. Further, physical activity has been shown to be a critical influence on maternal weight [22] and predicts postpartum weight retention (PPWR) 12 months after childbirth [22, 23]. In the interest of maternal health, a greater understanding of physical activity patterns during the postpartum period is required, yet the literature to date suggests an observed decline in physical activity following childbirth [5, 6, 24, 25].

Importantly, both PPWR and long term development and persistence of obesity in women [26–30] have been attributed to suboptimal maternal diet and physical activity behaviours. Results from systematic reviews of interventions aimed at limiting PPWR have consistently shown that the majority of successful studies have included both diet and physical activity intervention

components in their design [31]. Hence understanding factors which may promote healthy diet and physical activity behaviours is key to ensuring women receive the support they need to engage in these behaviours.

An important opportunity for provision of support lies with advice provided by antenatal healthcare clinicians. The antenatal period is a time in which women are in frequent contact with a wide range of health professionals [1, 14, 32], depending on their preferred choice of antenatal care. Obstetricians, general practitioners and midwives as well as other antenatal healthcare workers are routine providers of care within the antenatal system, which in some countries has been estimated to reach almost 100 % of the pregnant population [1, 32]. Moreover, health professionals are often viewed as authorities regarding maternal health information and advice both during [33, 34] and following pregnancy [35].

Compared to during pregnancy, less opportunity presents in the months following childbirth for women to be seen by healthcare practitioners. Formal, scheduled face-to-face practitioner and patient contact often occurs on fewer occasions during the postpartum period compared with during pregnancy, [36] and formal care is inconsistent between countries. In Australia for example, there are no standardised guidelines for the recommended frequency/schedule of routine postpartum visits to healthcare providers [37]. In the UK, however, formal guidelines such as the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommend that diet and physical activity advice be provided to women following childbirth [38]. The NICE guidelines also recommend a greater number of antenatal appointments with a health professional during pregnancy compared with the postpartum period [38]. Yet, whilst some postpartum education is provided for women by nursing and other healthcare professionals, much of the support is focused on breastfeeding and care of the newborn, rather than the physical health of the mother [39]. It is thus not surprising that primary care services for women during the postpartum period have been described as being inconsistent, fragmented across disciplines and not adequate in meeting population needs [37, 40].

There is very little known about the diet and physical activity advice women receive during the postpartum period. A better understanding of the provision of advice and recommendations women receive and if these are associated with diet and physical activity behaviours is necessary to identify opportunities for provision of healthy lifestyle support for new mothers during this unique life stage. The aims of this study were to (i) compare the frequency of dietary and physical activity advice provided by clinicians during pregnancy and in the postpartum period and (ii) assess if advice received by women is associated with maternal postpartum diet and physical activity behaviours in a sample of first time mothers.

Methods

Participants

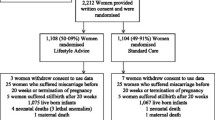

Participants were from the extended Melbourne Infant Feeding Activity and Nutrition Trial Program (InFANT Extend), a cluster-randomised controlled intervention trial which recruited first time mothers who attended first time parent groups at their local Maternal and Child Health Centres in Victoria. A two-stage random sampling design was used to select first time parent groups across all socio-economic areas. Areas eligible for local government area (LGA) selection were those areas which had not previously been involved in the earlier Melbourne InFANT trial (2008–2010) [41]. To ensure inclusion of a broad representation of socio- economic areas, each LGA was classified by socio-economic position (SEP) using the Australian Bureau of Statistics Socio-Economic Indices for Areas (SIEFA). Local Government areas with SEIFAs in the lowest quintile across the state were eligible. In the first stage, nine LGAs qualified to be approached for recruitment and seven agreed to take part.

In the second stage of recruitment, within the local government areas, 62 first-time parents groups were selected from the seven LGAs. For a group to be eligible, a minimum of eight participants were required to consent per first-time parent group within mid and higher SEP LGAs and six participants were required per first-time parent group within the lower SEP LGAs, as participation rates tend to be low in health behaviour interventions for vulnerable population groups or low socio-economic areas [42]. Parents needed to be English literate. When first-time parents groups declined to participate, another group was approached to take part. Written consent to participate was obtained and groups were then randomly allocated to intervention or control arms. The InFANT Extend trial was approved by the Deakin University \Human Research Ethics Committee (2011–029) (2007–175) (11/02/2011) and the Victorian Government Department of Human Services, Office for Children Research Co-ordinating Committee.

Measures

This study reports baseline data completed when mothers were approximately 3 months postpartum. Questionnaires were distributed to all mothers at the recruitment visit when women consented to take part in the study. Demographic and socioeconomic variables included maternal age, marital status, birth country, education level, employment level, smoking status (currently and during pregnancy), breastfeeding status and weekly household income level.

Anthropometry

Pre-pregnancy weight was self-reported. Postpartum weight was measured by trained research staff when women were approximately 3 months postpartum. Weight in light clothing and without shoes was measured once using Tanita digital scales (Model 1582) and recorded to the nearest 0.01 kg. Height was measured using a Victar stadiometer. All equipment used for anthropometry measurements were calibrated prior to the beginning of the InFANT Extend intervention. Two measurements were taken separately and were recorded to the nearest 0.1 cm. If the two measurements disagreed by 0.5 cm or more, a third measurement was taken and recorded. The average of the height measurements was used to calculate maternal pre- pregnancy BMI and postpartum BMI, calculated as weight (kg) / height (m2). Body Mass Index classification was according to World Health Organization criteria (underweight (BMI <18.5), healthy weight (BMI 18.5 to <25.0), overweight (BMI 25.0 to <30.0) or obese (BMI ≥ 30.0)) [43].

Dietary intake

Dietary intake was assessed using the Cancer Council of Victoria’s Dietary Questionnaire for Epidemiological Studies (DQES) version 3.1 Food Frequency Questionnaire [44]. The DQES has been previously validated against seven day weighed food records [45, 46] and has been shown to be a useful assessment of dietary intake in the Australian population [46, 47]. The DQES assesses usual food consumption over the previous 12 months and comprises a food list of 74 items with 10 frequency response options assessing frequency of intake from ‘never’ to ‘3 or more times per day’ [44]. These data were converted into daily equivalent frequencies (DEFs) according the Cancer Council of Victoria’s protocol and divided into several different food categories, including non-core foods. Several separate items asked women to report their usual intake of specific types and quantities of different core and non-core foods. One item asked women to report their usual intake of fruit (serves per day); a separate item assessed intake of vegetables (excluding potatoes) (serves per day); and one item assessed intake of non-diet soft drink (glasses per day). A serving sizes guide was given to assist in quantification of intake of these items. Fruit and vegetable intake responses were compared with Australian adult recommendations for daily fruit and vegetable intake [48].

Physical activity

Postpartum physical activity (duration and intensity) was assessed using the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare’s Active Australia Survey (AAS) [49, 50]. The AAS has been used frequently to assess physical activity in Australian adult populations [51–53], with established test – retest reliability and validity in Australian [52, 54–56] and US [57] adult populations and deemed similar to that of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire [50, 51]. The AAS has been also been previously validated against accelerometers in Australian [56] and US women [57].

Women were asked to estimate the total duration (number of times and total hours and minutes) of time they spent walking continuously (for at least 10 minutes) for recreation, exercise or to get from place to place, in the week prior to completing the questionnaire. They were also asked to estimate the total duration (number of times and total hours and minutes) of time they spent in moderate and vigorous activities which excluded household chores, gardening or yard work. Total physical activity time (min/week) was calculated by summing the total time spent walking, time spent in moderate physical activity and twice the time spent in vigorous physical activity, as per AAS scoring protocols [50]. To avoid the possibility of errors due to over- reporting, data for each activity type were truncated at 840 min/week (14 h). Total time in all activities was truncated at 1680 min/week (28 h). Categorical variables were created to define ‘sufficient minutes’ of physical activity (≥150 minutes per week), ‘sufficient sessions’ (≥5 sessions per week) and ‘sufficient activity’ (≥150 minutes per week plus ≥ 5 sessions per week) [50]. Physical activity levels were defined as either meeting recommendations (i.e. sufficient activity) or not. Women were classified as being ‘sedentary’ if their combined total time spent walking, in moderate activity and in vigorous activity was equal to zero, as per the survey protocol.

Clinician advice

Provision of clinician advice during pregnancy was measured by a single item which asked women if during their pregnancy, a doctor, nurse or other healthcare practitioner talked with them about dietary advice: ‘eating a healthy diet during pregnancy’ and physical activity advice: ‘being physically active during pregnancy’. Provision of clinician advice during the postpartum period was measured by a single item which asked women if, since delivering their baby, they had they received advice from their doctor, nurse or other healthcare worker about dietary advice: ‘eating a healthy diet’; or physical activity: ‘being physically active’.

Statistical analyses

Data were analysed using SPSS statistical package version 21, or for regression analyses assessing associations of clinician advice with maternal health behaviour, Stata Version 12 was used to allow controlling for clustering. Analyses included descriptive statistics to characterize the sample and distributions of key variables. Chi square tests were conducted to detect differences in the proportion of women who reported receiving advice during pregnancy compared to during the postpartum period. For associations of clinician advice with maternal diet and physical activity, linear regression was conducted when outcomes were continuous. Continuous outcome measures were checked for normality and when found to be non-normally distributed were transformed using root or log transformations. Binomial or multinomial logistic regression analyses were conducted when outcomes were categorical. Statistical significance was set as p <0.05 for all analyses.

Maternal age, education, income and BMI were adjusted for in the analysis when dietary and physical activity outcomes were assessed. Finally, clustering by first-time parents’ groups was accounted for in all models, using the ‘cluster by’ command in Stata. Adjustment for clustering within the analysis is necessary when assessing a cluster-randomised trial such as the Melbourne InFANT RCT [41] and accounts for the design effect and expected intra-cluster correlations of maternal characteristics within a first-time parent group.

Results

Women were excluded from the analysis in this study if they were not first time mothers (n = 15), if they had non-singleton pregnancies (n = 6) or if they had not provided detail regarding parity (n = 6). Survey data were missing for 2 women, leaving data for 448 women included in the analysis. Characteristics of these women are presented in Table 1.

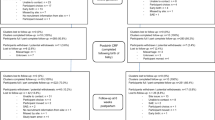

Dietary intake

Maternal dietary intakes are presented in Table 2. Overall, approximately half of all women (55.4 %) met fruit recommendations defined as 2 or more serves/day. 8.6 % of all women met recommendations for vegetable intake defined as 5 or more serves/day, with 44.9 % of women consuming 2 or fewer serves/day of vegetables [48]. Just 7.2 % of all women met recommendations for both fruit and vegetable intake. Approximately half (53.4 %) of all women reported consuming less than one glass of regular soft drink per day and approximately one third of all women (33.0 %) did not consume soft drink on a daily basis. Mean total non- core snack food DEF score, comprised of six non-core sweet and savoury snack foods, was 1.39 ± 1.18 and ranged from 0.02 – 10.85 DEF.

Physical activity

Physical activity levels are presented in Table 3. Overall, mean total PA time was 350.94 ± 281.10 min/week. Average time spent walking (251.97 ± 196.78 min/week) was greater than time spent in moderate (36.68 ± 88.58 min/week) or vigorous activity (61.74 ± 109.96 min/week). Overall, 63.2 % of women met PA recommendations defined as ≥150 minutes per week plus ≥ 5 sessions per week [50].

Clinician advice

Table 4 shows the proportion of women who reported receiving diet and physical activity advice during pregnancy and during the postpartum period, and associations of provision of advice during the postpartum period with maternal health outcomes at 3 months postpartum. A significantly higher proportion of women reported they had received advice for healthy eating during pregnancy (87.1 %) compared with during the postpartum period (47.5 %) (p < 0.01). Likewise, a significantly higher proportion of women reported receiving physical activity advice during pregnancy (82.8 %) compared with during the postpartum period (51.9 %) (p < 0.01). There was no significant association between the mothers being provided with dietary advice and meeting fruit or vegetable intake, soft drink or non-core food intake recommendations. For physical activity, no significant association was found between provision of clinician advice to be physically active and total physical activity time, time spent walking, or whether the women met physical activity recommendations.

Discussion

This study showed that relatively few women received advice regarding diet and physical activity in the period between childbirth and 3 months postpartum. It also showed that advice during the postpartum period was less commonly received compared with during pregnancy, and that practitioner advice was not associated with healthy postpartum diet and physical activity behaviours in this sample of first time mothers.

Importantly diet and physical activity levels in this sample were inadequate overall. Only half of the women in our study were meeting recommended intakes for fruit and less than 10 % for vegetables or combined fruit/vegetable intakes. The small number of previous studies that have assessed dietary intake in mothers, have similarly shown diet quality to be suboptimal for women during the postpartum period [14, 17]. From a public health perspective this is concerning given the well documented health benefits associated with optimal intakes with reduced chronic disease risk [8]. Therefore strategies which assist in promoting adequate fruit and vegetable intakes in mothers are vital to ensure optimizing maternal health and wellbeing in the short and long term.

On average, time spent walking was much greater than time spent in both moderate and vigorous physical activity amongst women in this study. This is not surprising, as walking has been previously found to be the most common form of physical activity for new mothers [58] and is a highly suitable form of physical activity for this population group. Walking is functional, low cost and low risk [59]. Further, the health benefits associated with walking are particularly relevant to new mothers. For example, in the U.S. an intervention study conducted by Davenport et al., [60] examined the effect of postpartum exercise intensity on chronic disease risk factors. They found that risk factors for chronic disease, including BMI, were significantly lower for women in the walking intervention groups, compared women in the control group [60]. Furthermore, there was no additional benefit seen for women in the higher intensity walking group, suggesting that even low intensity walking on most days of the week can be beneficial for the health of a new mother during the postpartum period. Elsewhere, achieving ≥30 minutes of walking per day has been associated with the prevention of weight retention at 1 year postpartum [25].

The results from our study showed that approximately two thirds of women engaged in physical activity which met recommendations defined as 150 min/week over ≥5 sessions, consistent with the 1999 national physical activity recommendations for Australian adults [61]. It should be noted, however that the more recently developed national physical activity guidelines in from 2014, differ slightly to the former recommendations. Regardless, promoting physical activity during the postpartum period is an important consideration both for greater chance of supporting reductions in PPWR, when combined with dietary strategies [31, 62], as well as assisting in the reduction of chronic disease risk.

Overall, just less than half of the sample of women in this study reported having received any dietary advice by 3 months postpartum, despite women having been shown to be particularly receptive to dietary information during the postpartum period [63]. Women have been described as being an ideal population for receiving nutrition education (149) and in the U.S., for example, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and the American Society for Nutrition recently recommended that women of reproductive age receive counselling on the importance of healthy eating including during the postpartum period [12, 64]. It may be that a lack of formal guidelines in Australia addressing dietary advice for new mothers might in part explain why many women had not received such education by 3 months postpartum.

Furthermore, almost half of the women in this study reported that they had not received advice about physical activity by 3 months postpartum. This is consistent with findings from elsewhere, whereby many women have reported not received advice at all to be physically active during the postpartum [65–67]. For example, in the U.S, Ferrari et al. (2010) assessed clinician’s provision of physical activity advice to women at 3 months postpartum [65] and found that the majority of women (89.1 %) reported receiving no physical activity advice (77.4 %) [65]. This omission of advice occurred against a backdrop of Institute of Medicine recommendations that physical activity counselling be included in postpartum care for all women [68], regardless of weight status. Similarly, in the UK national guidelines recommend that women are encouraged to keep a healthy diet and be physically active during and after pregnancy [38].

Moreover, the proportion of women who reported receiving both healthy eating advice and advice to be physically active was far less during the postpartum period compared with during pregnancy. In part, this might be due to less opportunity for women to see a healthcare practitioner during the postpartum period, for their own health as a focus, compared with during pregnancy. In the months following childbirth, a shift in focus from the health of the woman to the health of the newborn is not uncommon, making the opportunity for practitioners to engage with women regarding diet and physical activity during this time to be infrequent. Whilst it may be assumed that practitioner advice may lead to women adopting healthy behaviours, interestingly, this study showed that when advice was received, it did not predict healthy diet and physical activity behaviours. Likewise, a growing number of antenatal interventions have compared information provision (typically a brochure or meeting with health professional) with additional behaviour change strategies (such as goal setting and behavioural monitoring) and found that the information provision has very little or no impact on dietary behaviours [69] or physical activity [70]. Yet, other studies have shown positive associations of provision of weight advice during pregnancy, for example, with pregnancy weight gain [71, 72].

Provision of information alone may not be sufficient to change behaviour given the many potential barriers women face to both eating healthily and being sufficiently active during and after pregnancy, including lack of time, motivation, and prioritizing their own healthy eating secondary to the demands of having a child [33]. Strategies which account for unique barriers faced by women in the postpartum period are required. Barriers such as a lack of partner support, mothers returning to work, difficulties with childcare options and strong social expectations of the role of a new mother are also common and should be taken into account when planning supportive strategies to assist new mothers in optimizing healthy behaviours [16, 73, 74].

In addition, perhaps alternative strategies to the mere provision of advice might be more effective in engaging postpartum women and promoting healthy behaviour change. For example, current evidence suggests that women should be supported to self-monitor their weight or set and review behavioural goals in an effort to successfully change behaviours such as increasing physical activity [75, 76]. Techniques identified by research elsewhere during pregnancy, which have assisted healthy weight gain have included self-monitoring of behaviour, women being provided with information related to the consequences of behaviour to the individual and providing rewards contingent on successful behaviour, as well as motivational interviewing [77]. Nonetheless, from a public health perspective, there appears to be a need to support clinicians, through alternate strategies such as lifestyle intervention programs targeting improved diet and physical activity behaviours amongst postpartum women.

A strength of this study was the assessment of frequency of advice both related to diet and physical activity. Assessing provision of advice related to both lifestyle components is important, as it has previously been shown that lifestyle changes, including both dietary intake and physical activity in combination, are more likely to be successful in minimizing PPWR for example, rather than one behavior alone [31, 62, 78, 79]. Therefore understanding predictors of these behaviours is key to addressing opportunities for behavior change. A further strength of this study was comparison of the reported advice received during and following pregnancy. This comparison allows identification of gaps in current management strategies to be made, and showed that the postpartum period can be considered a missed opportunity at present, for provision of healthy lifestyle advice, thereby supporting the need for greater provision of support in the months following childbirth.

The main limitation of this study was the inability to determine what specific advice regarding weight, diet or physical activity was provided to women. This is an important consideration, for example regarding gestational weight gain, as when healthcare practitioners do use target weights for women as part of their practice, studies have shown that women often adhere to guidelines [71, 80, 81]. Provision of non-specific advice, such as clearly defined fruit and vegetable recommendations or physical activity recommendations, may have been one reason why no associations with advice and healthy lifestyle behaviours was seen, yet this is unable to be determined. Further, this sample of women were predominately highly educated and over half of the sample of women had moderate to high household income therefore limiting the generalizability of the results. Future research would ideally consider practitioner lifestyle advice provided to low income women to enable specific delivery of postpartum support amongst different population groups following childbirth.

Conclusion

This study showed that women reported receiving healthy eating and physical activity advice far less during the postpartum period, compared with during pregnancy. Moreover, when advice was provided to new mothers, it was not shown to be associated with healthy lifestyle behaviours. Additional investigation is warranted to identify effective forms of practitioner engagement to promote women’s diet and physical activity during the months following childbirth, to enable women to achieve optimal diet and physical activity habits for their own health benefit. Strategies which employ more intensive support, such as lifestyle interventions, tailored specifically to new mothers, as opposed to diet and physical activity advice only, is an important consideration for future research.

References

Streuling I, Beyerlein A, Rosenfeld E, Hofmann H, Schulz T, von Kries R. Physical activity and gestational weight gain: a meta-analysis of intervention trials. BJOG. 2011;118(3):278–84.

Haakstad LA, Voldner N, Bø K. Stages of change model for participation in physical activity during pregnancy. J Pregnancy. 2013;2013:1–7.

Saravanan P, Yajnik CS. Role of maternal vitamin B12 on the metabolic health of the offspring: a contributor to the diabetes epidemic? The British J Diabetes Vascular Disease. 2010;10(3):109–14.

Arrish J, Yeatman H, Williamson M. Midwives and nutrition education during pregnancy: A literature review. Women Birth. 2014;27:2–8.

Kalisiak B, Spitznagle T. What Effect Does an Exercise Program for Healthy Pregnant Women Have on the Mother, Fetus, and Child? PMR. 2009;1(3):261–6.

Kernot J, Olds T, Lewis L, Maher C. Effectiveness of a facebook-delivered physical activity intervention for post-partum women: a randomized controlled trial protocol. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):518.

Blum J, Beaudoin C, Caton-Lemos L. Physical Activity Patterns and Maternal Well- Being in Postpartum Women. Matern Child Health J. 2004;8(3):163–9.

Bassett-Gunter R, Levy-Milne R, Naylor PJ, Symons Downs D, Benoit C, Warburton DER, et al. Oh baby! Motivation for healthy eating during parenthood transitions: a longitudinal examination with a theory of planned behavior perspective. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10(1):88.

WHO: Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003.

Hiza HAB, Casavale KO, Guenther PM, Davis CA. Diet Quality of Americans Differs by Age, Sex, Race/Ethnicity, Income, and Education Level. J Acad Nut Diet. 2013;113(2):297–306.

Pignone MP, Ammerman A, Fernandez L, Orleans CT, Pender N, Woolf S, et al. Counseling to promote a healthy diet in adults: A summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24(1):75–92.

Falciglia G, Piazza J, Ritcher E, Reinerman C, Lee SY. Nutrition Education for Postpartum Women: A Pilot Study. J Prim Care Commun Health. 2014;5(4):275–8.

de Jersey SJ, Nicholson JM, Callaway LK, Daniels LA. An observational study of nutrition and physical activity behaviours, knowledge, and advice in pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:115.

Wiltheiss GA, Lovelady CA, West DG, Brouwer RJN, Krause KM, Østbye T. Diet Quality and Weight Change among Overweight and Obese Postpartum Women Enrolled in a Behavioral Intervention Program. J Acad Nut Diet. 2013;113(1):54–62.

George GC, Milani TJ, Hanss-Nuss H, Freeland-Graves JH. Compliance with Dietary Guidelines and Relationship to Psychosocial Factors in Low-Income Women in Late Postpartum. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105(6):916–26.

Wilkinson SA, van der Pligt P, Gibbons KS, McIntyre HD: Trial for Reducing Weight Retention in New Mums: a randomised controlled trial evaluating a low intensity, postpartum weight management programme. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics 2013

Fowles E, Walker L. Correlates of dietary quality and weight retention in postpartum women. J Community Health Nurs. 2006;23:183–97.

Durham HA, Morey MC, Lovelady CA, Namenek Brouwer RJ, Krause KM, Ostbye T. Postpartum Physical Activity in Overweight and Obese Women. J Phys Act Health. 2011;8(7):988–93.

SongØYgard KM, Stafne SN, Evensen KAI, Salvesen KÅ, Vik T, MØRkved SIV. Does exercise during pregnancy prevent postnatal depression? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012;91(1):62–7.

O'Toole ML, Sawicki MA, Artal R. Structured Diet and Physical Activity Prevent Postpartum Weight Retention. J Womens Health. 2003;12(10):991–8.

Schlussel MM, Souza EB, Reichenheim ME, Kac G. Physical activity during pregnancy and maternal-child health outcomes: a systematic literature review. Cad Saude Publica. 2008;24 Suppl 4:s531–44.

Hodge A, Patterson AJ, Brown WJ, Ireland P, Giles G. The Anti Cancer Council of Victoria FFQ: relative validity of nutrient intakes compared with weighed food records in young to middle-aged women in a study of iron supplementation. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2000;24(6):576–83.

Mamun AA, O'Callaghan M, Callaway L, Williams G, Najman J, Lawlor DA. Associations of Gestational Weight Gain With Offspring Body Mass Index and Blood Pressure at 21 Years of Age: Evidence From a Birth Cohort Study. Circulation. 2009;119(13):1720–7.

Albright CL, Maddock JE, Nigg CR. Physical Activity Before Pregnancy and Following Childbirth in a Multiethnic Sample of Healthy Women in Hawaii. Women Health. 2006;42(3):95–110.

Pereira MA, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman KP, Rich-Edwards JW, Peterson KE, Gillman MW. Predictors of Change in Physical Activity During and After Pregnancy: Project Viva. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(4):312–9.

Besson H, Ekelund U, Luan J, May AM, Sharp S, Travier N, et al. A cross-sectional analysis of physical activity and obesity indicators in European participants of the EPIC-PANACEA study. Int J Obes. 2009;33(4):497–506.

Stamatakis E, Hirani V, Rennie K. Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and sedentary behaviours in relation to body mass index-defined and waist circumference-defined obesity. Br J Nutr. 2009;101(5):765–73.

Weinsier RL, Hunter GR, Heini AF, Goran MI, Sell SM. The etiology of obesity: relative contribution of metabolic factors, diet, and physical activity. Am J Med. 1998;105(2):145–50.

Rezazadeh A, Rashidkhani B. The Association of General and Central Obesity with Major Dietary Patterns of Adult Women Living in Tehran, Iran. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol. 2010;56(2):132–8.

Wane S, van Uffelen JGZ, Brown W. Determinants of Weight Gain in Young Women: A Review of the Literature. J Womens Health. 2010;19(7):1327–40.

van der Pligt P, Willcox J, Hesketh KD, Ball K, Wilkinson S, Crawford D, et al. Systematic review of lifestyle interventions to limit postpartum weight retention: implications for future opportunities to prevent maternal overweight and obesity following childbirth. Obes Rev. 2013;14(10):792–805.

Draper A, Swift JA. Qualitative research in nutrition and dietetics: data collection issues. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2011;24(1):3–12.

Olander EK, Atkinson L, Edmunds JK, French DP. The views of pre- and post-natal women and health professionals regarding gestational weight gain: An exploratory study. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2011;2(1):43–8.

Szwajcer EM, Hiddink GJ, Koelen MA, van Woerkum CMJ. Nutrition-related information-seeking behaviours before and throughout the course of pregnancy: consequences for nutrition communication. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59(S1):S57–65.

Brown S, Lumley J. Maternal health after childbirth: results of an Australian population based survey. BJOG. 1998;105(2):156–61.

Reeves MM, Healy GN, Owen N, Shaw JE, Zimmet PZ, Dunstan DW. Joint associations of poor diet quality and prolonged television viewing time with abnormal glucose metabolism in Australian men and women. Prev Med. 2013;57(5):471–6.

McDonald SD, Pullenayegum E, Taylor VH, Lutsiv O, Bracken K, Good C, et al. Despite 2009 guidelines, few women report being counseled correctly about weight gain during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(4):333.e331-333.e336.

Excellence NIfHaC. NICE public health guidance 27: Dietary interventions and physical activity interventions for weight management before, during and after pregnancy, vol. In: NICE public health guidance 27. London, UK: NICE; 2010.

Knight-Agarwal CR, Kaur M, Williams LT, Davey R, Davis D: The views and attitudes of health professionals providing antenatal care to women with a high BMI: A qualitative research study. Women and Birth 2013, In press.

Schmied V, Mills A, Kruske S, Kemp L, Fowler C, Homer C. The nature and impact of collaboration and integrated service delivery for pregnant women, children and families. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(23–24):3516–26.

Lioret S, Campbell KJ, Crawford D, Spence AC, Hesketh K, McNaughton SA. A parent focused child obesity prevention intervention improves some mother obesity risk behaviors: the Melbourne inFANT program. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:100.

Organization WH. Waist Circumference and Waist-Hip ratio: Report of WHO Expert Consultation., vol. 8–11. Geneva: WHO; 2008.

WHO. Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health. What is overweight and obesity? In: WHO 2011. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/.

Victoria CCo: Dietary Questionnaire for Epidemiological Studies Version 2 (DQES v2): User Guide 2014. Victoria Cancer Council of Victoria 2014.

Niedhammer I, Bugel I, Bonenfant S, Goldberg M, Leclerc A. Validity of self- reported weight and height in the French GAZEL cohort. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24(9):1111–8.

Tiggemann M. Body image across the adult life span: stability and change. Body Image. 2004;1(1):29–41.

Baker C, Carter A, Cohen L, Brownell K. Eating attitudes and behaviors in pregnancy and postpartum: Global stability versus specific transitions. Ann Behav Med. 1999;21(2):143–8.

Ageing. NHMRC: Dietary Guidelines for Australian Adults In. Australia National Health and Medical Research Council 2003.

Welfare AIHW. The Active Australia Survey: A guide and manual for implementation, analysis and reporting. vol. cat.no.CVD22. AIHW: Canberra; 2003.

AIHW. Active Australia Survey: A guide for analysis and reporting. In: Book Active Australia Survey: A guide for analysis and reporting. 2003.

Snijder MB, Zimmet PZ, Visser M, Dekker JM, Seidell JC, Shaw JE. Independent and opposite associations of waist and hip circumferences with diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidemia: the AusDiab Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28(3):402–9.

Klein S, Allison DB, Heymsfield SB, Kelley DE, Leibel RL, Nonas C, et al. Waist Circumference and Cardiometabolic Risk: A Consensus Statement from Shaping America's Health: Association for Weight Management and Obesity Prevention; NAASO, The Obesity Society; the American Society for Nutrition; and the American Diabetes Association. Obesity. 2007;15(5):1061–7.

Fanghänel G, Sánchez-Reyes L, Félix-García L, Violante-Ortiz R, Campos-Franco E, Alcocer LA. Impact of waist circumference reduction on cardiovascular risk in treated obese subjects. Cirugia Y Cirujanos. 2011;79(2):175–81.

Clapp Iii JF, Capeless EL. Neonatal morphometrics after endurance exercise during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;163(6, Part 1):1805–11.

Owe KM, Nystad W, Bø K. Correlates of regular exercise during pregnancy: the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2009;19(5):637–45.

Zhang J, Savitz DA. Exercise during pregnancy among US women. Ann Epidemiol. 1996;6(1):53–9.

Petersen AM, Leet TL, Brownson RC. Correlates of physical activity among pregnant women in the United States. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37(10):1748–53.

Timperio A, Salmon J, Crawford D. Validity and reliability of a physical activity recall instrument among overweight and non-overweight men and women. J Sci Med Sport. 2003;6(4):477–91.

Nascimento SL, Pudwell J, Surita FG, Adamo KB, Smith GN. The effect of physical exercise strategies on weight loss in postpartum women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes. 2014;38(5):626–35.

Davenport MH, Giroux I, Sopper MM, Mottola MF. Postpartum exercise regardless of intensity improves chronic disease risk factors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(6):951–8.

National Health and medical Research Council, Department of Health and Ageing: National Physical Activity Guidelines for Australians In. Edited by DHAC, vol. http://fulltext.ausport.gov.au/fulltext/1999/feddep/physguide.pdf. Canberra 1999.

Amorim AR, Linne YM, Lourenco PM. Diet or exercise, or both, for weight reduction in women after childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (Online). 2007;3:CD005627.

Olson CM. Tracking of Food Choices across the Transition to Motherhood. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2005;37(3):129–36.

American Dietetic A, American Society of N, Siega-Riz AM, King JC. Position of the American Dietetic Association and American Society for Nutrition: obesity, reproduction, and pregnancy outcomes. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(5):918–27.

Ferrari RM, Siega-Riz AM, Evenson KR, Moos M, Melvin CL, Herring AH. Provider advice about weight loss and physical activity in the postpartum period. J Womens Health. 2010;19(3):397–406.

Evenson KR, Brouwer RJN, Østbye T. Changes in Physical Activity Among Postpartum Overweight and Obese Women: Results from the KAN-DO Study. Women Health. 2013;53(3):317–34.

Heesch KC, Hill RL, van Uffelen JGZ, Brown WJ. Are Active Australia physical activity questions valid for older adults? J Sci Med Sport. 2011;14(3):233–7.

National Health and Medical Research Council, Department of Health and Ageing: Eat for Health. Australian Dietary Guidelines. Summary. vol. 2013: Natioanl Health and Medical Research Council 2013

Guelinckx I, Devlieger R, Mullie P, Vansant G. Effect of lifestyle intervention on dietary habits, physical activity, and gestational weight gain in obese pregnant women: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(2):373–80.

Harrison CL, Lombard CB, Strauss BJ, Teede HJ. Optimizing healthy gestational weight gain in women at high risk of gestational diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. Obesity. 2013;21(5):904–9.

Cogswell ME, Scanlon KS, Fein SB, Schieve LA. Medically Advised, Mother's Personal Target, and Actual Weight Gain During Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94(4):616–22.

Brawarsky P, Stotland NE, Jackson RA, Fuentes-Afflick E, Escobar GJ, Rubashkin N, et al. Pre-pregnancy and pregnancy-related factors and the risk of excessive or inadequate gestational weight gain. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2005;91(2):125–31.

Miller YD, Trost SG, Brown WJ. Mediators of physical activity behavior change among women with young children. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23:98–103.

Watson N, Milat AJ, Thomas M, Currie J. The feasibility and effectiveness of pram walking groups for postpartum women in western Sydney. Health Promot J Austr. 2005;16(2):93–9.

Currie S, Sinclair M, Murphy MH, Madden E, Dunwoody L, Liddle D. Reducing the decline in physical activity during pregnancy: a systematic review of behaviour change interventions. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e66385.

Gilinsky AS, Dale H, Robinson C, Hughes AR, McInnes R, Lavallee D. Efficacy of physical activity interventions in post-natal populations: systematic review, meta- analysis and content coding of behaviour change techniques. Health Psychol Rev. 2014;9(2):244–63.

Hill B, Skouteris H, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M. Interventions designed to limit gestational weight gain: a systematic review of theory and meta-analysis of intervention components. Obes Rev. 2013;14(6):435–50.

Keller C, Records K, Ainsworth B, Permana P, Coonrod DV. Interventions for Weight Management in Postpartum Women. J Obstetric Gynecologic Neonatal Nursing. 2008;37(1):71–9.

Kuhlmann AKS, Dietz PM, Galavotti C, England LJ. Weight-Management Interventions for Pregnant or Postpartum Women. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(6):523–8.

Herring SJ, Rose MZ, Skouteris H, Oken E. Optimizing weight gain in pregnancy to prevent obesity in women and children. Diabetes Obesity Metabol. 2012;14:195–203.

Stotland NE, Haas JS, Brawarsky P, Jackson RA, Fuentes-Afflick E, Escobar GJ. Body Mass Index, Provider Advice, and Target Gestational Weight Gain. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(3):633–8.

Acknowledgements

The InFANT-Extend study, within which this study was nested was funded by a World Cancer Research Fund grant (2010/244). PV is funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Postgraduate Scholarship; KB is supported by a NHMRC Principal Research Fellowship, ID 1042442 (the contents of this work are the responsibility of the authors and do not reflect the views of NHMRC); KDH is supported by an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (FT130100637) and Honorary National Heart Foundation of Australia Future Leader Fellowship (100370).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

PV and KC conceived this study and KC, KB, KH and DC advised on the study design. PV assisted with study recruitment, data collection and conducted the statistical analysis. PV drafted the manuscript together with EO. All authors contributed to the critical revision of the paper and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

van der Pligt, P., Olander, E.K., Ball, K. et al. Maternal dietary intake and physical activity habits during the postpartum period: associations with clinician advice in a sample of Australian first time mothers. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 16, 27 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-0812-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-0812-4