Abstract

Backgrounds

The reports of neurological symptoms are increasing in cases with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). This multi-center prospective study was conducted to determine the incidence of neurological manifestations in hospitalized cases with COVID-19 and assess these symptoms as the predictors of severity and death.

Methods

Hospitalized males and females with COVID-19 who aged over 18 years were included in the study. They were examined by two neurologists at the time of admission. All survived cases were followed for 8 weeks after discharge and 16 weeks if their symptoms had no improvements.

Results

We included 873 participants. Of eligible cases, 122 individuals (13.97%) died during hospitalization. The most common non-neurological manifestations were fever (81.1%), cough (76.1%), fatigue (36.1%), and shortness of breath (27.6%). Aging, male gender, co-morbidity, smoking, hemoptysis, chest tightness, and shortness of breath were associated with increased odds of severe cases and/or mortality. There were 561 (64.3%) cases with smell and taste dysfunctions (hyposmia: 58.6%; anosmia: 41.4%; dysguesia: 100%). They were more common among females (69.7%) and non-smokers (66.7%). Hyposmia/anosmia and dysgeusia were found to be associated with reduced odds of severe cases and mortality. Myalgia (24.8%), headaches (12.6%), and dizziness (11.9%) were other common neurological symptoms. Headaches had negative correlation with severity and death due to COVID-19 but myalgia and dizziness were not associated. The cerebrovascular events (n = 10) and status epilepticus (n = 1) were other neurological findings. The partial or full recovery of smell and taste dysfunctions was found in 95.2% after 8 weeks and 97.3% after 16 weeks. The parosmia (30.9%) and phantosmia (9.0%) were also reported during 8 weeks of follow-up. Five cases with mild headaches and 5 cases with myalgia were reported after 16 weeks of discharge. The demyelinating myelitis (n = 1) and Guillain-Barré syndrome (n = 1) were also found during follow-up.

Conclusion

Neurological symptoms were found to be prevalent among individuals with COVID-19 disease and should not be under-estimated during the current pandemic outbreak.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The novel virus from the coronaviridae family termed as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was first discovered in December, 2019 after many pneumonia cases with unknown cause were identified in Wuhan, China [1]. The SARS-CoV-2 is a β-coronavirus which is an enveloped virus with helical nucleocapsid and non-segmented positive ribonucleic acid that can infect mammals [2,3,4,5]. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) as a pandemic outbreak on March 11th, 2020. Over 80 million confirmed cases and about 2 million deaths due to COVID-19 were recorded until the end of 2020 [6].

Several non-respiratory symptoms have been reported in individuals with COVID-19. The reports of neurological features are increasing but few large sample-sized studies reported the incidence of neurological disorders in people with COVID-19. Myalgia, headaches, and loss of smell (anosmia) and taste (dysgeusia) sensations are common neurological findings of the disease [7,8,9]. Recent studies showed that SARS-CoV-2 could manifest as life-threatening neurological conditions including ischemic stroke, subarachnoid hemorrhage, status epilepticus, and acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis [10,11,12,13]. Neurological symptoms were also reported in epidemic outbreaks of other coronaviruses including SARS-CoV and the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)-CoV [14, 15]. The direct invasion of coronaviruses to the nervous system and over-production of pro-inflammatory cytokines could be the plausible underlying mechanisms [16]. This study aimed to determine the incidence of neurological manifestations in hospitalized cases with COVID-19 and assess these symptoms as predictors of severity and death.

Methods

Study design and participants

This was a prospective hospital-based cohort study conducted in Loghman, Imam Hossein, and Imam Khomeini hospitals, the three major referral hospitals in Tehran province, Iran. Males and females aged above 18 years who were diagnosed with COVID-19 based on WHO recommendations [17] were included in the study. The sterile nasopharyngeal swabs were inserted in one nostril of each participant. The collected specimens were placed into tubes containing viral transport medium; stored at 4o C to 8o C and were sent to laboratories within 12 h. The positive results of real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay using a SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid detection kit (PCR Fluorescence Probing of Sansure Biotech, Changsha, China) could confirm COVID-19. The exclusion criteria were the presence of other respiratory infections (e.g. tuberculosis), loss of competence and no access to surrogates, and withdrawal of consent.

The ethics committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences approved the study. The protocol was explained to all participants and if they lacked decision-making capacity, their legal surrogates were informed about the study. The printed protocol was also given. It was explained that participation in the study was optional and the identity information would remain confidential and not published. Written informed consent was obtained before the initiation of the study.

Data collection

All eligible inpatients were interviewed and the demographic characteristics including gender, age, smoking status, and co-morbidities were recorded. Participants were examined and chest computed tomography (CT) was performed in all cases. The laboratory tests included cell blood count, quantitative C-reactive protein (CRP), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and procalcitonin. The severity of COVID-19 was determined using American Thoracic Society recommendations for community-acquired pneumonia [18].

To assess neurological manifestations, two neurologists with at least 5 years of experience took a detailed history and examined all participants. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion with each other or consultation with another neurologist. Headaches were known to be associated with COVID-19 if they fulfilled the criteria for ‘Headache attributed to systemic viral infection’ according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders [19]. Brain CT and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), electroencephalography (EEG), electromyography and nerve conduction velocity (EMG-NCV), as well as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis were conducted if clinically indicated. Smell and taste dysfunctions were assessed in cases using a self-reporting tool. The National Institute of Health stroke scale (NIHSS) was used to evaluate the severity of ischemic stroke. The NIHSS was designed to objectively quantify neurological impairments in stroke and consisted of 11 items [20]. Each item can be scored from 0 to 4 and the total possible scores ranged from 0 to 42. Neurological impairments can be divided into four categories using NIHSS: a. mild (0–4), b. moderate (5–15), c. Moderate to severe (16–20), and d. severe (21–42). The intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) score was also calculated in participants with ICH. This is a clinical grading scale using Glasgow Coma Scale, age, the presence of infratentorial origin, ICH volume, and the presence of intraventricular hemorrhage to predict the ICH mortality [21]. The total score ranged from 0 to 6.

Most included cases were followed for 8 weeks after discharge from hospital to assess the course of their neurological manifestations. If their neurological symptoms were persistent, they were followed for further 8 weeks. Cellphone and telephone numbers of each participant were recorded and they were interviewed via phone once per 4 weeks by a neurologist. If cases reported any new-onset neurological complaints, they would be asked to visit the hospital for further assessments. A phone number was also given to participants so physical complaints could be reported as soon as possible. Participants were asked to go to the emergency department if serious events occurred.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as means with standard deviation (SD) and compared between groups using independent sample t test. Categorical variables were described as numbers with percentages and compared between groups using Pearson’s chi-squared test. To more rigorously assess the predictors of severity and death due to COVID-19, odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated using univariate and multivariate logistic regression.. The calculated ORs of neurological manifestations were adjusted for gender, age, smoking status, and co-morbidity. All analyses were conducted using the IBM SPSS Software version 25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Two sided significance testing was performed and p-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Participants

The study was initiated on April 7, 2020 when the clinical characteristics of the first hospitalized participant were assessed. The follow-up of survived cases lasted until November 18, 2020. Primary screening was performed on 1269 inpatients and 873 cases were included in the study (Fig. 1). Of eligible participants, 122 individuals died during hospitalization (case fatality rate: 13.97%) and 751 cases were discharged in 11.41 ± 6.20 (mean ± SD) days. There were 62 participants who were lost to follow-up and 689 individuals completed the study.

Non-neurological characteristics

The demographic clinical features of included cases during hospitalization were presented in Table 1. There were 551 males (63.7%) and 317 females (36.3%). The mean ± SD age of participants was 60.71 ± 18.14 years and 459 individuals (52.6%) aged over 60 years. The most common non-neurological manifestations were fever (708/873, 81.1%), cough (664/873, 76.1%), fatigue (315/873, 36.1%), and shortness of breath (241/873, 27.6%). Our analysis showed that aging (severity: OR: 1.020, 95%CI: 1.012 to 1.028; death: OR: 1.08, 95%CI: 1.06 to 1.99), male gender (severity: OR: 1.38, 95%CI: 1.03 to 1.86), presence of co-morbidity (OR: 1.43, 95%CI: 1.11 to 1.98; death: OR: 2.81, 95%CI: 1.79 to 4.42), smoking (severity: OR: 1.62, 95%CI: 1.11 to 2.34; death: 2.69, 95%CI: 1.73 to 4.18), hemoptysis (severity: OR: 3.55, 95%CI: 2.01 to 6.28; death: OR: 2.30, 95%CI: 1.21 to 4.36), chest tightness (severity: OR: 3.23, 95%CI: 2.09 to 5.00; death: OR: 2.63, 95%CI: 1.60 to 4.32), and shortness of breath (severity: OR: 2.51, 95%CI: 1.84 to 3.41; death: OR: 9.61, 95%CI: 6.25 to 14.92) were associated with increased odds of severity and/or death in participants.

The most common laboratory abnormalities were elevated CRP (542/873, 61.2%), lymphocytopenia (434/873, 49.7%), elevated LDH (316/873, 35.7%), and neutrophilia (291/873, 33.3%) (Table 2). The statistical analysis showed that the elevated procalcitonin (severity: OR: 2.26, 95%CI: 1.35 to 3.78; death: OR: 5.40; 95%CI: 3.12 to 9.34), elevated LDH (severity: OR: 1.99, 95%CI: 1.49 to 2.65; death: OR: 10.63; 95%CI: 6.53 to 17.24), neutrophilia (severity: OR: 1.68, 95%CI: 1.26 to 2.26; death: OR: 3.10; 95%CI: 2.09 to 4.58), elevated CRP (severity: OR: 1.46, 95%CI: 1.09 to 1.96; death: OR: 6.17; 95%CI: 3.40 to 11.11), leukocytosis (death: OR: 1.62, 95%CI: 1.04 to 2.53), and lymphocytopenia (severity: OR: 1.36, 95%CI: 1.03 to 1.81) were associated with increased odds of severity and/or death due to COVID-19.

Neurological manifestations

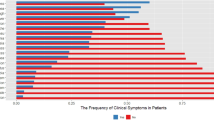

Smell and taste dysfunctions were reported in 561 (64.3%) included cases at the time of admission (hyposmia: 329/561 or 58.6%; anosmia: 232/561 or 41.4%; dysgeusia: 561/561 or 100%). They were more common among females (69.7%) than males (OR: 1.46, 95%CI: 1.08 to 1.96) and also more frequent among non-smokers (66.7%) than smokers (OR: 1.91, 95%CI: 1.32 to 2.77). Co-morbidities were more frequent among cases with normal smell and taste sensations (OR: 1.42, 95%CI: 1.07 to 1.89). There were 28 cases with rhinorrhea and 17 cases with nasal congestion who reported loss of smell sensation. Of 561 participants, 142 individuals (25.3%) reported these symptoms as the first clinical manifestation. Hyposmia/anosmia and dysgeusia were found to be associated with reduced odds of severe cases (OR: 0.69, 95%CI: 0.52 to 0.94) and death (OR: 0.63, 95%CI: 0.39 to 0.95) after adjustment for gender, age, smoking status, co-morbidity, rhinorrhea, and nasal congestion (Table 3, Fig. 2).

Myalgia (217/873 or 24.9%), headaches (110/873 or 12.6%), and dizziness (104/873 or 11.9%) were other common neurological symptoms. The incidence rates of these conditions were not significantly different among genders. Of 110 individuals with headaches, 71 cases (64.5%) had migraine-like episodes; 37 participants (33.6%) had tension-like headaches; and 2 cases (1.9%) had only cough-related headaches. Headaches had negative correlation with severity (adjusted OR: 0.52, 95%CI: 0.32 to 0.85) and death due to COVID-19 (adjusted OR: 0.37, 95%CI: 0.75 to 0.92) but myalgia and dizziness were not associated (Table 3, Fig. 2).

There were 10 cases (1.26%) with COVID-19 who presented cerebrovascular events (Table 4). The mean age was 63.40 years (SD: 20.55). Brain CT scans were performed in all cases and ischemic stroke was found in 7 patients (70%) and 3 cases (30%) were diagnosed with ICH. Of cases with ischemic stroke, mild impairment was observed in 1 case with NIHSS < 5. We found 3 cases with moderate (NIHSS: 5–15), 1 case with moderate to severe (NIHSS: 16–20), and 2 cases with severe (NIHSS > 21) neurological impairments. The ICH score of 4 was calculated in 2 cases and the score of 3 was calculated in 1 patient with ICH. Fever (n = 10), cough (n = 8), fatigue (n = 7), myalgia (n = 3), and headaches (n = 1) were reported in 10.7 ± 2.91 days prior to cerebrovascular events but none were severe COVID-19 cases. Six patients (60%) died in 4.15 ± 2.23 days after hospitalization.

One previously healthy 28 year-old-female was referred to Loghman hospital with status epilepticus as the sole clinical manifestation. No history of physical disorders, head trauma, drug use, or recent respiratory symptoms was reported from parents. Physical examination revealed bilateral mydriatic and non-reactive pupils with downward gaze. The EEG showed moderate to severe diffuse slowing and generalized rhythmic delta activity. She was intubated and received intravenous levetiracetam (3000 mg) and generalized tonic-clonic seizure occurred within 2 h of drug administration. Intravenous midazolam was, then, added. No other convulsive seizures were developed during hospitalization. Bilateral ground glass opacities were observed in chest CT and the RT-PCR test for COVID-19 was positive. Cerebrospinal (CSF) analysis showed clear appearance with no cells, protein: 79 mg/dl (normal: 15–45), glucose: 135 mg/dl (normal: 45–80), and opening pressure: 22 cmH2O (normal: 6–25). The PCR panel of CSF was negative for herpes simplex and no bacterial or fungal organisms were detected. Other laboratory data showed thrombocytopenia (n = 43,000) at the time of admission but other tests were in normal limits (leukocytes: 5.1 × 103/μL, Na: 142, K: 4.4, Ca: 9.4, Albumin: 3.4, and Mg: 2.1). Urine toxicology analysis for methanol, methadone, benzodiazepines, cannabinoids, methamphetamine, tramadol, and opiates were negative. The primary brain CT scans showed no specific abnormalities but the top of basilar infarction was observed after ten days of hospitalization (Fig. 3 a, b). The patient died 16 days after admission.

Follow-up

There were 442 individuals with hyposmia/anosmia and dysgeusia who survived from COVID-19 and completed the study. It was found that after 4 weeks of discharge, 209 cases (47.3%) fully recovered from these conditions; 181 cases (40.9%) had partial improvements; and 52 cases (11.8%) reported no changes in their smell and taste dysfunctions. The full recovery was reported in 302 individuals (68.3%) after 8 weeks of discharge and partial improvements were found among 119 participants (26.9%). Twenty one cases (4.8%) with hyposmia (n = 15) and anosmia (n = 6) reported no changes (Fig. 4). Intermittent parosmia (distortion of odor perception when an odor is present) was reported in 42 cases (9.5%) after 4 weeks and 137 cases (30.9%) after 8 weeks of discharge. Intermittent phantosmia (odor perception in the absence of odor stimulus) was also reported in 11 cases (2.5%) after 4 weeks and 40 cases (9.0%) after 8 weeks of discharge (Fig. 4). These events occurred in 86 cases (48.6%) with recovered hyposmia/anosmia, 83 cases (46.9%) with partial improvements, and eight case (4.5%) with no smell and taste improvements.

Headaches were reported among 37 of 689 individuals after 4 weeks of discharge (5.3%) (28 cases with migraine-like and 9 cases with tension-like headaches) and 14 cases (2.0%) after 8 weeks (11 cases with migraine-like and 3 cases with tension-like headaches). These individuals had no prior history of headaches (e.g. migraine). The severity was mild to moderate and headaches were well-controlled with simple analgesics. No functional impairments were reported among affected individuals due to headaches. There were 21 participants (3.0%) after 4 weeks and 9 cases (1.3%) after 8 weeks of discharge with myalgia. Dizziness was also reported among 9 individuals after 4 weeks that was recovered after 8 weeks of discharge (Fig. 4).

The follow-up was continued in participants with parosmia, phantosmia, no improvements in smell and taste, headaches, and myalgia (Fig. 4). The full recovery was reported in 9 cases (6.6%) with parosmia, 3 cases (5.0%) with phantosmia, 2 cases (9.5%) with no prior changes in smell and taste sensations, 9 cases (64.3%) with headaches, and 4 cases with myalgia (44.4%) after 8 further weeks of follow-up (16 weeks after discharge). Partial improvements were reported in 64 cases (46.7%) with parosmia, 12 cases with phantosmia (30.0%), and 7 cases (33.3%) with no prior changes in smell and taste sensations after 16 weeks of discharge. The remaining cases with headaches had mild migraine-like episodes.

Demyelinating myelitis

One 43-year-old-male visited Loghman hospital after 16 days of prior admission with weakness, paresthesia, and paresis of upper and lower limbs. The patient also developed low abdominal pain with urinary retention. No history of similar symptoms and neurological disorders were reported. The initial manifestations due to COVID-19 were fever, fatigue, myalgia, and headaches that were recovered after discharge. Neurological examinations showed reduced forces of upper (4 / 5) and lower limbs (2 / 5). The deep tendon reflexes of all extremities were normal (1+) and Babinski’s sign was present. The position, vibration, and light tough sensations were impaired in lower limbs. The laboratory data including leukocyte count, CRP, and LDH were normal. The CSF analysis showed clear appearance with no cells, protein: 60 mg/dl, glucose: 43 mg/dl, and opening pressure: 18 cmH2O. The PCR panel of CSF was negative for herpes simplex and no bacterial or fungal organisms were detected. The CSF was assessed to detect anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) antibody, oligoclonal band, aquaporin-4 receptor (AQP-4), and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibodies which were negative. Serological testing for the anti-nuclear antibody, anti-phospholipid antibodies, neuromyelitis optica, anti-NMDA, AQP-4, and MOG antibodies was also negative. The brain and spinal cord MRI showed bilateral thalamic hypersignal lesions (Fig. 3c) with longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis at cervical and thoracic cord levels (Fig. 3 d, e). The patient was diagnosed with post-infectious demyelinating myelitis and managed with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) for 7 days. Our patient was discharged from hospital after 16 days with significant improvements in forces of upper (5 / 5) and lower limbs (4 / 5).

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS)

A 46-year-old-female visited Imam Hossein hospital after 21 days of prior admission with weakness and paresthesia of upper and lower limbs as well as bilateral facial paralysis. The initial symptoms due to COVID-19 were fever and dry cough that were recovered after discharge. Neurological examination showed decreased forces of upper (4 / 5) and lower limbs (3 / 5) with mild bilateral peripheral facial nerve palsy. The deep tendon reflexes of all extremities were absent. The CSF analysis showed no cells, protein: 93 mg/dl, glucose: 15 mg/dl, and opening pressure: 18 cmH2O. The EMG-NCV was conducted and acute axonal motor neuropathy (AMAN) variant of GBS was diagnosed. The motor nerve conduction and F-wave response were measured on the median, ulnar, tibial, and peroneal nerves. The sensory nerve conduction was measured using median, ulnar, and sural nerves. The normal NCV without evidence of conduction block, and normal sensory nerve action potential (SNAP) amplitude along with reduced compound muscle action potential (CMAP) amplitude were found in both upper and lower extremities. The electromyographic findings were reduced voluntary recruitment and increased insertional activity. The patient was treated with five consequent days of IVIG but the disease progressed and she developed dyspnea and was intubated. Arrhythmia due to autonomic dysfunction was also developed and pacemaker was inserted. The IVIG was used for further 7 days. The symptoms improved gradually and the patient was discharged after 42 days of hospitalizations with improvements in forces of lower limbs (4 / 5).

Discussion

The COVID-19 is the third outbreak of coronaviruses after SARS and MERS, which occurred in 2002 and 2012; respectively. The SARS and MERS diseases led to less than 2000 deaths but the current pandemic outbreak of COVID-19 has claimed more than one million lives in less than a year. All three viruses were found to involve vital organ systems including nervous system [22,23,24]. The incidence of neurological manifestations was assessed in our study among hospitalized individuals with positive RT-PCR of SARS-CoV-2. The smell and taste dysfunctions were the third most common symptoms in our cases after fever and cough. It was identified that about two-third of our participants experienced smell and taste dysfunctions that resolved partially or completely in 98% of cases after 16 weeks of discharge from hospital. Myalgia (25%), headaches (13%), dizziness (12%), and cerebrovascular events (1%) were also reported in participants. Three individuals presented status epilepticus, post-infectious demyelinating myelitis, and AMAN variant of GBS.

The involvement of nervous system in COVID-19 disease can be attributed to the direct invasion of virus or secondary para-infectious mechanisms. The SARS-CoV-2 was found to enter the human cells using angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors [25] that can be expressed on nasal goblet and ciliated epithelial cells as well as oligodendrocytes [26, 27]. The detection of the SARS-CoV-2 in the CSF of cases with encephalopathy [28, 29] and demyelinating disorder [30] was an important clue to show that the virus could be neuroinvasive. Furthermore, viral particles were found in the brain tissue of cases with the COVID-19 disease [31, 32]. It should be noted that these results should be interpreted with caution [33]. Small numbers of cases were identified and some studies reported no evidence of the SARS-CoV-2 detection in the CSF or brain tissue of confirmed COVID-19 cases with neurological symptoms [34, 35]. The hyper-inflammatory state due to over-production of cytokines (e.g. interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor) also known as “cytokine storm” was reported to be another plausible underlying mechanism of neuronal damage in COVID-19 disease [36].

Several studies reported that hyposmia/ anosmia and dysgeusia were about 20 to 98% prevalent among confirmed cases with COVID-19 [7, 8, 37,38,39]. The discrepancies in results can be due to the methodological differences. The study design, sample size, recruitment setting (inpatients vs. outpatients), and model of testing smell sensation (self-reporting survey vs. physical exam) could significantly affect the results. It was found that anosmia was more common in non-hospitalized individuals than hospitalized ones with COVID-19 [40, 41]. Our study showed that loss of smell and taste was associated with reduced odds of severe cases and death due among hospitalized cases. A recent study on 576 inpatients also demonstrated that cases with anosmia had lower mortality rate and less severe course of the disease [42]. The follow-up of individuals with the COVID-19 and hyposmia/ anosmia was assessed in few studies. An observational cohort study reported that over 70% of cases with smell and taste dysfunctions had early improvements after 4 weeks of onset of anosmia [43]. The recovery in all cases was reported in another study in 28 days [44]. A 6-month follow-up study on 434 individuals showed that over 70% had full or almost full recovery of loss of smell and about 2% of cases reported no improvements [45]. It was also reported that over 40% of participants developed parosmia with the median interval of 2.5 months after the onset of smell dysfunction [45]. Our study also showed that about 10% of cases with hyposmia/anosmia developed parosmia after 4 weeks of discharge that increased to over 30% after 8 weeks. Longer follow-up periods are needed to assess the prognosis of altered smell functions.

A systematic literature review estimated that myalgia (28.5%) and headaches (14%) were common manifestations of COVID-19 [46]. In consistent with this study, it was previously found that headaches were independent predictors of lower risk of mortality among hospitalized cases [47]. We found that migraine-like episodes were the most frequent phenotype of headaches among the participants. A recent study also showed that headaches were common manifestations in COVID-19 and they were mostly presented as bilateral severe headaches at the time of admission with migraine phenotype [48] Individuals who diagnosed with COVID-19 were found to be at 0.5 to 1.3% risk of subsequent cerebrovascular events including ischemic stroke, ICH, and cerebral venous thrombosis [10, 49]. It was reported that among individuals with COVID-19 and stroke, older age, higher baseline NIHSS, and cryptogenic stroke were associated with early mortality [50].

To date, few cases with post-infectious demyelinating conditions of the central nervous system (CNS) after the COVID-19 disease were diagnosed [13, 51]. The structure and replication of SARS-CoV-2 was reported to be similar with mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) [52]. The MHV was found to remain in mouse CNS after acute infection and could induce an immune-mediated, chronic demyelinating disease, similar to multiple sclerosis in humans [33, 53]. We found two individuals with the CNS demyelination in our medical centers (51, present study) during COVID-19 pandemic outbreak. Future longitudinal studies should assess the prevalence of these events in confirmed COVID-19 cases. The post-infectious demyelination of peripheral nervous system was also reported after recovery from COVID-19 disease. The GBS is a relatively rare disease with the incidence ranged from 0.81 to 1.89 per 100,000 person-years [54]. Of 873 hospitalized individuals in our study, one case developed AMAN variant of GBS. Another study with 1200 patients also reported the incidence of 0.4% for GBS [55]. Systematic review studies reported that the majority of cases with COVID-19 and GBS had acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculopolyneuropathy (AIDP) variant [56, 57]. The facial nerve palsy that was observed in our participant was also found in about half of the prior reported cases [56].

To our knowledge, this was the first multi-center prospective study assessed the course of different neurological manifestations associated with COVID-19 disease. The prospective design of the study could reduce the possible information bias. The study was also multi-center that can increase the external validity. There were some limitations to our study. Some symptoms including anosmia and dysgeusia are often under-reported by patients with severe disease and our results could be affected by this measurement bias. Participants were sampled from hospitals rather than community (hospital based vs. population based studies). This can lead to selection bias (Berkson’s bias); as many individuals with mild severity were not included in our study. A short period of follow-up and lacking control group were other major limitations that should be resolved in future studies. Some neurological symptoms (e.g. smell and taste sensations, headaches, and myalgia) were not objectively assessed and were reliant on individuals’ reports. Further studies should be conducted to assess the incidence of CNS demyelinating events and evaluate the course of altered smell sensation including parosmia and phantosmia.

Conclusions

Neurological symptoms are prevalent among individuals with the COVID-19 and should not be under-estimated during the current pandemic outbreak. The smell and taste dysfunctions and headaches were common neurological symptoms that were associated with less severe cases and lower mortality rates.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AQP-4:

-

Aquaporin-4 receptor

- AIDP:

-

Acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculopolyneuropathy

- AMAN:

-

Acute axonal motor neuropathy

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CMAP:

-

Compound muscle action potential

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- EEG:

-

Electroencephalography

- EMG-NCV:

-

Electromyography and nerve conduction velocity

- GBS:

-

Guillain-Barré syndrome

- ICH:

-

Intracerebral hemorrhage

- IVIG:

-

Intravenous immunoglobulin

- LDH:

-

Lactate dehydrogenase

- MERS:

-

Middle East respiratory syndrome

- MOG:

-

Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NIHSS:

-

National Institute of Health stroke scale

- NMDA:

-

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- RT-PCR:

-

Reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction

- SARS-CoV:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SNAP:

-

Sensory nerve action potential

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5.

Guo YR, Cao QD, Hong ZS, Tan YY, Chen SD, Jin HJ, Tan KS, Wang DY, Yan Y. The origin, transmission and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak–an update on the status. Mil Med Res. 2020;7(1):11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-020-00240-0.

Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, Si HR, Zhu Y, Li B, Huang CL, Chen HD. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270–3. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7.

Zhang T, Wu Q, Zhang Z. Probable pangolin origin of SARS-CoV-2 associated with the COVID-19 outbreak. Curr Biol. 2020;30(7):1346–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.022.

Malaiyan J, Arumugam S, Mohan K, Gomathi RG. An update on the origin of SARS-CoV-2: despite closest identity, bat (RaTG13) and pangolin derived coronaviruses varied in the critical binding site and O-linked glycan residues. J Med Virol Published Online July 7. 2020;(1):499–505. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.26261.

Worldometers. COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. Worldometers 2020.

Lechien JR, Chiesa-Estomba CM, De Siati DR, Horoi M, Le Bon SD, Rodriguez A, Dequanter D, Blecic S, El Afia F, Distinguin L, Chekkoury-Idrissi Y. Olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions as a clinical presentation of mild-to-moderate forms of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a multicenter European study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;277(8):2251–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-020-05965-1.

Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, Hu Y, Chen S, He Q, Chang J, Hong C, Zhou Y, Wang D, Miao X. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(6):683–90. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127.

Nepal G, Rehrig JH, Shrestha GS, Shing YK, Yadav JK, Ojha R, Pokhrel G, Tu ZL, Huang DY. Neurological manifestations of COVID-19: a systematic review. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):421. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-03121-z.

Shahjouei S, Naderi S, Li J, Khan A, Chaudhary D, Farahmand G, Male S, Griessenauer C, Sabra M, Mondello S, Cernigliaro A, Khodadadi F, Dev A, Goyal N, Ranji-Burachaloo S, Olulana O, Avula V, Ebrahimzadeh SA, Alizada O, Hancı MM, Ghorbani A, Vaghefi far A, Ranta A, Punter M, Ramezani M, Ostadrahimi N, Tsivgoulis G, Fragkou PC, Nowrouzi-Sohrabi P, Karofylakis E, Tsiodras S, Neshin Aghayari Sheikh S, Saberi A, Niemelä M, Rezai Jahromi B, Mowla A, Mashayekhi M, Bavarsad Shahripour R, Sajedi SA, Ghorbani M, Kia A, Rahimian N, Abedi V, Zand R. Risk of stroke in hospitalized SARS-CoV-2 infected patients: a multinational study. EBioMedicine. 2020;59:102939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102939.

Avci A, Yesiloglu O, Avci BS, Sumbul HE, BugraYapici S, Kuvvetli A, Pekoz BC, Cinar H, Satar S. Spontaneous subarachnoidal hemorrhage in patients with Covid-19: case report. J Neuro-Oncol. 2020;26(5):802–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13365-020-00888-3.

Swarz JA, Daily S, Niemi E, Hilbert SG, Ibrahim HA, Gaitanis JN. COVID-19 infection presenting as acute-onset focal status epilepticus. Pediatr Neurol. 2020;112:7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2020.07.012.

McCuddy M, Kelkar P, Zhao Y, Wicklund D. Acute Demyelinating Encephalomyelitis (ADEM) in COVID-19 infection: A Case Series. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.15.20126730.

Tsai L, Hsieh S, Chang Y. Neurological manifestations in severe acute respiratory syndrome. Acta Neurol Taiwanica. 2005;14(3):113–9.

Arabi YM, Harthi A, Hussein J, Bouchama A, Johani S, Hajeer AH, Saeed BT, Wahbi A, Saedy A, AlDabbagh T, Okaili R. Severe neurologic syndrome associated with Middle East respiratory syndrome corona virus (MERS-CoV). Infection. 2015;43(4):495–501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-015-0720-y.

Ellul M, Benjamin L, Singh B, Lant S, Michael B, Kneen R, Defres S, Sejvar J, Solomon T. Neurological Associations of COVID-19. 2020;19(9):767–783.

World Health Organization. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when Novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection is suspected: interim guidance. 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/330893

Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, Anzueto A, Brozek J, Crothers K, Cooley LA, Dean NC, Fine MJ, Flanders SA, Griffin MR. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. An official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(7):e45–67. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201908-1581ST.

Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1–211.

Brott T, Adams HP Jr, Olinger CP, Marler JR, Barsan WG, Biller J, Spilker J, Holleran R, Eberle R, Hertzberg V. Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: a clinical examination scale. Stroke. 1989;20(7):864–70. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.20.7.864.

Hemphill JC 3rd, Bonovich DC, Besmertis L, Manley GT, Johnston SC. The ICH Score: a simple, reliable grading scale for intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2001;32(4):891–897, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.32.4.891.

Umapathi T, Kor AC, Venketasubramanian N, Lim CT, Pang BC, Yeo TT, Lee CC, Lim PL, Ponnudurai K, Chuah KL, Tan PH. Large artery ischaemic stroke in severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). J Neurol. 2004;251(10):1227–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-004-0519-8.

Kwong KC, Mehta PR, Shukla G, Mehta AR. COVID-19, SARS and MERS: a neurological perspective. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;77:13–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2020.04.124.

Khatoon F, Prasad K, Kumar V. Neurological manifestations of COVID-19: available evidences and a new paradigm. J Neuro-Oncol. 2020;26(5):619–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13365-020-00895-4.

Li G, He X, Zhang L, Ran Q, Wang J, Xiong A, Wu D, Chen F, Sun J, Chang C. Assessing ACE2 expression patterns in lung tissues in the pathogenesis of COVID-19. J Autoimmun. 2020;13:102463.

Sardu C, Gambardella J, Morelli MB, Wang X, Marfella R, Santulli G. Is COVID-19 an endothelial disease? Clinical and basic evidence. Preprints. 2020. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202004.0204.v1.

Aghagoli G, Marin BG, Katchur NJ, Chaves-Sell F, Asaad WF, Murphy SA. Neurological involvement in COVID-19 and potential mechanisms: a review. Neurocrit Care. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-020-01049-4.

Moriguchi T, Harii N, Goto J, Harada D, Sugawara H, Takamino J, Ueno M, Sakata H, Kondo K, Myose N, Nakao A. A first case of meningitis/encephalitis associated with SARS-Coronavirus-2. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:55–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.062.

Virhammar J, Kumlien E, Fällmar D, Frithiof R, Jackmann S, Sköld MK, Kadir M, Frick J, Lindeberg J, Olivero-Reinius H, Ryttlefors M. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy with SARS-CoV-2 RNA confirmed in cerebrospinal fluid. Neurology. 2020;95(10):445–9. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000010250.

Domingues RB, Mendes-Correa MC, de Moura Leite FB, Sabino EC, Salarini DZ, Claro I, Santos DW, de Jesus JG, Ferreira NE, Romano CM, Soares CA. First case of SARS-COV-2 sequencing in cerebrospinal fluid of a patient with suspected demyelinating disease. J Neurol. 2020;267(11):3154–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-020-09996-w.

Paniz-Mondolfi A, Bryce C, Grimes Z, Gordon RE, Reidy J, Lednicky J, Sordillo EM, Fowkes M. Central nervous system involvement by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2). J Med Virol. 2020;92(7):699–702. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25915.

Puelles VG, Lütgehetmann M, Lindenmeyer MT, Sperhake JP, Wong MN, Allweiss L, Chilla S, Heinemann A, Wanner N, Liu S, Braun F. Multiorgan and renal tropism of SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(6):590–2. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2011400.

Pezzini A, Padovani A. Lifting the mask on neurological manifestations of COVID-19. Nat Rev Neurol. 2020;16(11):636–44. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-020-0398-3.

Schaller T, Hirschbühl K, Burkhardt K, Braun G, Trepel M, Märkl B, Claus R. Postmortem examination of patients with COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323(24):2518–20. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.8907.

Solomon IH, Normandin E, Bhattacharyya S, Mukerji SS, Keller K, Ali AS, Adams G, Hornick JL, Padera RF Jr, Sabeti P. Neuropathological features of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(10):989–92. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2019373.

Pedersen SF, Ho YC. SARS-CoV-2: a storm is raging. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(5):2202–5. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI137647.

Aggarwal S, Garcia-Telles N, Aggarwal G, Lavie C, Lippi G, Henry BM. Clinical features, laboratory characteristics, and outcomes of patients hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): early report from the United States. Diagnosis. 2020;7(2):91–6. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2020-0046.

Giacomelli A, Pezzati L, Conti F, Bernacchia D, Siano M, Oreni L. Self-reported olfactory and taste disorders in SARS-CoV-2 patients: a cross-sectional study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020; Published online March 26, 2020.

Moein ST, Hashemian SM, Mansourafshar B, Khorram-Tousi A, Tabarsi P, Doty RL. Smell dysfunction: a biomarker for COVID-19. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2020. Published online: April 17, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/alr.22587, Smell dysfunction: a biomarker for COVID‐19;8:950.

Giorli A, Ferretti F, Biagini C, Salerni L, Bindi I, Dasgupta S, Pozza A, Gualtieri G, Gusinu R, Coluccia A, Mandalà M. A literature systematic review with meta-analysis of symptoms prevalence in Covid-19: the relevance of olfactory symptoms in infection not requiring hospitalization. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2020;22(10):1–4.

Avcı H, Karabulut B, Farasoglu A, Boldaz E, Evman M. Relationship between anosmia and hospitalisation in patients with coronavirus disease 2019: an otolaryngological perspective. J Laryngol Otol. 2020;134(8):710–6. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022215120001851.

Talavera B, García-Azorín D, Martínez-Pías E, Trigo J, Hernández-Pérez I, Valle-Peñacoba G, Simón-Campo P, de Lera M, Chavarría-Miranda A, López-Sanz C, Gutiérrez-Sánchez M. Anosmia is associated with lower in-hospital mortality in COVID-19. J Neurol Sci. 2020;419:117163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2020.117163.

Hopkins C, Surda P, Whitehead E, Kumar BN. Early recovery following new onset anosmia during the COVID-19 pandemic–an observational cohort study. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;49:1–6.

Paolo G. Does COVID-19 cause permanent damage to olfactory and gustatory function? Med Hypotheses. 2020;143:110086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2020.110086.

Hopkins C, Surda P, Vaira LA, Lechien JR, Safarian M, Saussez S, Kumar N. Six month follow-up of self-reported loss of smell during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rhinology. 2020. https://doi.org/10.4193/rhin20.544.

Fu L, Wang B, Yuan T, Chen X, Ao Y, Fitzpatrick T, Li P, Zhou Y, Lin Y, Duan Q, Luo G. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Inf Secur. 2020;80(6):656–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.041.

Trigo J, García-Azorín D, Planchuelo-Gómez Á, Martínez-Pías E, Talavera B, Hernández-Pérez I, Valle-Peñacoba G, Simón-Campo P, de Lera M, Chavarría-Miranda A, López-Sanz C. Factors associated with the presence of headache in hospitalized COVID-19 patients and impact on prognosis: a retrospective cohort study. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):94. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-020-01165-8.

Sampaio Rocha-Filho PA, Magalhães JE. Headache associated with COVID-19: frequency, characteristics and association with anosmia and ageusia. Cephalalgia. 2020;40(13):1443–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102420966770.

Li Y, Wang M, Zhou Y, Chang J, Xian Y, Mao L, Hong C, Chen S, Wang Y, Wang H, Li M. Acute cerebrovascular disease following COVID-19: a single center, retrospective, observational study. SSRN Electron J. 2020;19. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3550025.

Ramos-Araque ME, Siegler JE, Ribo M, Requena M, López C, de Lera M, Arenillas JF, Pérez IH, Gómez-Vicente B, Talavera B, Portela PC. Stroke etiologies in patients with COVID-19: the SVIN COVID-19 multinational registry. BMC Neurol. 2021;21(1):43. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-021-02075-1.

Zoghi A, Ramezani M, Roozbeh M, Darazam IA, Sahraian MA. A case of possible atypical demyelinating event of the central nervous system following COVID-19. Multiple Sclerosis Related Disord. 2020;44:102324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2020.102324.

Lampert PW, Sims JK, Kniazeff AJ. Mechanism of demyelination in JHM virus encephalomyelitis. Acta Neuropathol. 1973;24(1):76–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00691421.

Hosking MP, Lane TE. The pathogenesis of murine coronavirus infection of the central nervous system. Crit Rev Immunol. 2010;30(2):119–30. https://doi.org/10.1615/CritRevImmunol.v30.i2.20.

Sejvar JJ, Baughman AL, Wise M, Morgan OW. Population incidence of Guillain-Barré syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroepidemiology. 2011;36(2):123–33. https://doi.org/10.1159/000324710.

Toscano G, Palmerini F, Ravaglia S, Ruiz L, Invernizzi P, Cuzzoni MG, Franciotta D, Baldanti F, Daturi R, Postorino P, Cavallini A. Guillain–Barré syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(26):2574–6. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2009191.

Sriwastava S, Kataria S, Tandon M, Patel J, Patel R, Jowkar A, Daimee M, Bernitsas E, Jaiswal P, Lisak RP. Guillain Barré syndrome and its variants as a manifestation of COVID-19: a systemic review of case report and case series. J Neurol Sci. 2021;420:117263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2020.117263.

Abu-Rumeileh S, Abdelhak A, Foschi M, Tumani H, Otto M. Guillain–Barré syndrome spectrum associated with COVID-19: an up-to-date systematic review of 73 cases. J Neurol. Published online 25 August. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-020-10124-x.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all patients for their participation in this study.

Funding

The Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences provided financial and logistic support for this trial but had no role in study design, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MA, NR, and MaR conducted the study design. AT and EK assessed neurological symptoms in Imam Khomeini hospital. MeR and MaS assessed neurological symptoms in Loghman hospital. AZ and IAD assessed neurological symptoms in Imam Hossein hospital. MA and MoS performed the interpretation of data and statistical analysis. MA and BSL prepared the draft of the manuscript. AG and AV revised the paper before submission. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The procedures were fully explained to the participants. Ethics committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences approved the final methods. All individuals were informed that participation was optional and withdrawal was possible whenever they asked for. Written informed consent was obtained from all individuals and next of kin or legally authorized representative for the participants who died during the study period.

Consent for publication

The consent for publication of information and images in online open-access journal was obtained.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Amanat, M., Rezaei, N., Roozbeh, M. et al. Neurological manifestations as the predictors of severity and mortality in hospitalized individuals with COVID-19: a multicenter prospective clinical study. BMC Neurol 21, 116 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-021-02152-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-021-02152-5