Abstract

Background

Idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder (iRBD) affects 1–2% of people over 60 years of age and presents a high risk of developing a neurodegenerative disorder from the group of synucleinopathies, such as Parkinson’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies and multiple system atrophy. Therefore, screening tools are needed. In 2007, the rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder screening questionnaire (RBD-SQ) was developed and has been translated into several languages. The aim of study was to assess the validity and reliability of the Czech version of the RBD-SQ in a mixed population of sleep clinic patients, supplemented by healthy volunteers and RBD patients.

Methods

Participants included 81 iRBD patients, 205 patients with other sleep disorders (obstructive sleep apnea, insomnia, restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder, other parasomnias, or central hypersomnias including narcolepsy) and 20 healthy volunteers.

Results

The mean RBD-SQ score in the iRBD patients was 9.4 ± 2.8 points, and in the non-RBD group it was 4.5 ± 3.0 (P < 0.0001). Receiver -operator analysis yielded an area under the curve of 0.864, suggesting good diagnostic performance of the scale. When using a cut-off value for positivity of 5 points, sensitivity was 0.89 and specificity was 0.62.

Conclusions

The Czech version of the RBD-SQ is a sensitive tool for screening for iRBD patients and helps to identify subjects for complete clinical workup.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder (RBD) is defined as a repetitive occurrence of vocalization and/or complex motor behavior and impaired muscle atonia during REM sleep [1]. In the general population, the prevalence of RBD is 0.38–2.1% [2, 3]. The idiopathic form of RBD (iRBD) is an important risk factor for later development of neurodegenerative disorders from the group of alpha-synucleinopathies [4, 5]. Patients suffering from iRBD are suitable candidates for neuroprotective therapy; therefore, effective screening of these patients is important. However, a definite diagnosis of RBD is made by means of night polysomnography, which is costly, time consuming and, thus, can only be performed on a limited number of individuals. Therefore, a highly sensitive and sufficiently specific detection of potential RBD patients is a logical step in the detection of RBD cases on a population scale. The first line among methods for such screening are self-administered questionnaires. The first specific method for RBD screening - RBD-SQ (REM sleep Behavior Disorder Screening Questionnaire) was published in 2007, and consists of 13 questions answered either “yes” or “no”, with each positive answer scoring 1 point [6]. RBD-SQ has also been validated in several languages outside of Europe, including Turkey, Japan, Korea and China [7,8,9,10,11]. Another screening tool, the REM sleep Behavior Disorder Questionnaire-Hong Kong (RBDQ-HK) [12], was published three years later, and in addition to actual symptoms of RBD it includes items for evaluating the occurrence of symptoms for one year prior to administration. Other questionnaires for RBD screening include the Mayo Sleep Questionnaire [13, 14], the Innsbruck REM sleep behavior disorder inventory [15] and a single question screen for rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder [16].

RBD-SQ is the most broadly used tool and the aim of our study was to validate the Czech version of the questionnaire.

Methods

A total of 306 participants of two sleep centers in Prague were included in the study and were then divided into three groups: 1) 205 adult patients of the mixed population (excluding iRBD), 2) 20 healthy volunteers and 3) 81 patients with RBD.

The mixed sleep population patients in the first group were further sub-divided into five sub-groups: 1) Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), 2) restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movements in sleep (RLS/PLMS), 3) insomnia, 4) parasomnias - both non-REM and REM (other than iRBD), and 5) central hypersomnia (including narcolepsy).

All of the participants, including healthy volunteers, were examined by videopolysomnography. REM sleep without atonia (RWA) was scored according to the ICSD3 criteria [1] with the suggested montage including the upper extremities [17], and was detected in all of the iRBD patients, and also in four patients with parasomnias other than RBD, in three healthy volunteers, and in one RLS, one narcolepsy and one OSA patient.

Cognitive impairment was excluded in all of the participants including healthy controls using the validated Czech version of Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) [18], and all underwent a clinical neurological examination. None of participants from the iRBD group met the diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease or Lewy body dementia and none had a history of any other neurological or psychiatric disorder. In addition, the iRBD patients previously participated in our web based survey, which is described elsewhere [19]. At the time of completing the questionnaire, all of the participants were free of any psychoactive medication and had signed the informed consent. The study was conducted according to the declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the General University Hospital in Prague.

Double reverse translation of the RBD-SQ from Czech to English and German was performed and the resulting Czech version is present in Table 1. All of the participants stated Czech language as their mother tongue and all completed this version. The participants were instructed to answer the questions according to their lifelong occurrence of the mentioned symptoms and also include an opinion of their bed partners, if applicable.

Statistical analyses were performed using the Dell Statistica (a data analysis software system), version 13.0. (software.dell.com).Non-parametric tests were used (Mann-Whitney U-test - MWU, Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA) for intergroup comparisons of the RBD-SQ scores.

Results

The mean RBD-SQ score was 9.4 ± 2.8 in RBD patients, and 4.5 ± 3.0 in the whole non-RBD sub-group including the healthy volunteers (P < 0.0001 MWU test). The mean RBD-SQ score in individual sub-groups was as follows: OSA 4.0 ± 3.2, RLS/PLMS 3.8 ± 3.0, insomnia 4.3 ± 2.5, non-RBD parasomnias 6.8 ± 2.9, hypersomnias 5.0 ± 3.0 and healthy volunteers 3.5 ± 2.7.All of the sub-groups significantly differed from the iRBD group. The RBD-SQ had a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.843, showing good consistency of the test [20]. All demographic data are summarized in Table 2.

The lowest sensitivity was found for item 10 (42.5%), which ask for the history of neurological diseases. Further items with low sensitivity values were items 9 (48.8%), 4 (51%) and 8 (58.8%). In these items, the participants were asked to recall disturbed sleep, limb movements, and the content of their dreams, respectively.

The highest sensitivity was found for items 1 (93.8%), 6.2 (93.8%) and 6.1. (91.3%), which asked about vivid dreams, sleep vocalization and violent and/or sudden limb movements in sleep, respectively. However, item 1 (vivid dreams) had a low specificity, with as many as 80% of the healthy controls answering positively. Patients in the RLS/PLMS sub-group frequently answered positively to item 7, 8 and 9 (awakening due to limb movements, dream recall and disturbed sleep, respectively). In item 4 (awareness of limb movements), patients with RBD gave significantly more positive answers than the RLS/PLMS patients (p = 0.003). Diagnostic profile of individual questions is presented in Table 3.

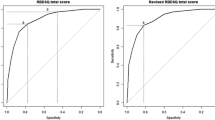

The receiver-operator curve of the total score yielded AUC 0.864, suggesting good overall diagnostic performance of the RBD-SQ. When using a cutoff value of 5 points as proposed by the questionnaire’s authors, the sensitivity was 95.1% (95% confidence interval 88.0 to 98.1%) and specificity 59.6% (95% confidence interval 53.0 to 65.8%).

There were more male participants in the study than female (63.4% of the whole study sample). When analyzing positive responses to individual questionnaire item between males and female in the whole sample, there were significant differences for the following items: item 3 (positive in 24.6% women versus 42.5% men, p = 0.00175), item 5 (positive 16.4% versus 39.4%, p = 0.00003), item 6.1 (positive 50% versus 64.3%, p = 0.015), item 6.2 (positive 21.8% versus 50.3%, p = 0.00001), item 6.3 (positive 18.2% versus 43.5%, p = 0.00001), and item 7 (positive 30.0% versus 45.6%, p = 0.008). In the iRBD sub-group, we found no differences in distribution of responses between men and women.

The range of answers to item 8 (dream recollection) was not significantly different among any of the tested sub-groups, not even between the RBD patients and the healthy controls. In addition, for item 9 (disturbed night sleep), the RBD patients provided similar answers to the OSA, insomnia, RLS and parasomnia patients.

Discussion

Our study proved that the Czech version of the RBD-SQ has sufficient validity and reliability for screening for RBD, and represents the first such study among Slavic languages.

The total score of 5 points represents the best cut off value for discrimination between iRBD patients and the other participants, including the healthy controls. We replicated the findings of the original publication: sensitivity 97.3% (the value lies within the 95% CI of our findings), and specificity 45.9% (slightly lower than our result) [6]. The same cut of value of 5 was replicated also in the Chinese and Japanese studies [9, 10]. The Italian validation study suggested raising the cutoff to 8, whereby increasing the specificity to 78%, but lowering the sensitivity to 84.2% [8].

The highest total score was in the iRBD group, and the lowest was in the group of healthy volunteers, with all of the other sub-groups having intermediate values, but still significantly different from the RBD group. This finding corresponds to unspecific positive responses common for other sleep problems, such as vivid dreaming, awareness of limb movements or disturbed sleep.

When analyzing the diagnostic accuracy of the individual items of the RBD-SQ, we confirmed lower specificity of item 1, 8, 9 and 10 similar to the previous publications [6, 8]. Positivity of item 1 was found in many other conditions than RBD, suggesting that vivid dreaming is also common across sleep pathologies. Recollection of these dreams in item 8 and disturbed night sleep in item 9 share the same characteristics. The Italian validation study suggested keeping item 10 as a clinically relevant indicator of possible false positive screening or a secondary form of RBD, but not to include it in the overall score [8]. Our data confirmed that this question had a moderate specificity (68.6%) in our set of iRBD patients.

RBD is characterized by behavior reflecting dream content and such motor activity may be dangerous for the patient and/or the bed-partner [21]. These symptoms are covered by items 5,6.2,6.3 and 6.4 and show the highest specificity and sensitivity, which is also in accordance with the original publication of the RBD-SQ [6].

Men are more frequently affected by RBD, usually it presents itself after the age of 60y [22]. In our sample, we found intersex differences in the way the items of the RBD-SQ were answered, and significantly in the case of items 3, 5, 6.1–6.3 and 7, suggesting that enacting dream content in women is generally less aggressive and less dangerous [23]. However, when analyzing only the iRBD sub-group, intersex differences are no longer significant, partly because of the low number of women (n = 9) with iRBD in our sample and the subsequent low statistical power.

Our study had several limitations. Despite being asked to include information from bed-partners, most patients completed the questionnaire in the sleep clinic, when their partners were not present. The healthy volunteers were relatively younger and their number was smaller. Moreover, all of the iRBD patients were older compared to other sub-groups and all had an idiopathic form of RBD.

However, the use of the RBD-SQ represents the first and broadest screening step in diagnostic workup for RBD. Therefore, it is important to know the diagnostic accuracy of this tool and expect false positive and false negative results based on the given application. For screening purposes, false negative results should be avoided as much as possible as they may lead to patients not being diagnosed. On the other hand, false positive screening may lead to costly and time-consuming polysomnography, which may turn out to be negative. This phenomenon occurs in at least 16% of healthy volunteers [24]. In addition, the use of multiple different RBD screening questionnaires may lead to conflicting results [25].

Conclusions

The Czech version of the RBD-SQ represents a validated and reliable screening tool for the detection of RBD, with diagnostic accuracy similar to the original publication of the German version. It can be administered to a population of patients visiting a general practitioner or specialist (sleep clinic, neurology) and may help in indicating the requirement for further investigation and polysomnography.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- iRBD:

-

Idiopathic form of the RBD

- MDS-UPDRS:

-

Movement disorder society Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale

- MoCA:

-

Montreal cognitive assessment

- MWU:

-

Mann-Whitney U-test

- OSA:

-

Obstructive sleep apnea

- RBD:

-

Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder

- RBD-SQ:

-

RBD screening questionnaire

- REM:

-

Rapid eye movement

- RLS/PLMS:

-

Restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movements in sleep

- RWA:

-

REM sleep without atonia

References

American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders. 3rd ed. Darien, IL; 2014.

Kang SH, Yoon IY, Lee SD, Han JW, Kim TH, Kim KW. REM sleep behavior disorder in the Korean elderly population: prevalence and clinical characteristics. Sleep. 2013;36(8):1147–52.

Pujol M, Pujol J, Alonso T, Fuentes A, Pallerola M, Freixenet J, Barbe F, Salamero M, Santamaria J, Iranzo A. Idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder in the elderly Spanish community: a primary care center study with a two-stage design using video-polysomnography. Sleep Med. 2017;40:116–21.

Iranzo A, Fernandez-Arcos A, Tolosa E, Serradell M, Molinuevo JL, Valldeoriola F, Gelpi E, Vilaseca I, Sanchez-Valle R, Llado A, et al. Neurodegenerative disorder risk in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder: study in 174 patients. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e89741.

Iranzo A, Molinuevo JL, Santamaria J, Serradell M, Marti MJ, Valldeoriola F, Tolosa E. Rapid-eye-movement sleep behaviour disorder as an early marker for a neurodegenerative disorder: a descriptive study. The Lancet Neurology. 2006;5(7):572–7.

Stiasny-Kolster K, Mayer G, Schafer S, Moller JC, Heinzel-Gutenbrunner M, Oertel WH. The REM sleep behavior disorder screening questionnaire--a new diagnostic instrument. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society. 2007;22(16):2386–93.

Tari Comert I, Pelin Z, Aricak T, Yapan S: Validation of the Turkish version of the rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder questionnaire. Behav Neurol 2016, 2016:8341651.

Marelli S, Rancoita PM, Giarrusso F, Galbiati A, Zucconi M, Oldani A, Di Serio C, Ferini-Strambi L. National validation and proposed revision of REM sleep behavior disorder screening questionnaire (RBDSQ). J Neurol. 2016;263(12):2470–5.

Miyamoto T, Miyamoto M, Iwanami M, Kobayashi M, Nakamura M, Inoue Y, Ando C, Hirata K. The REM sleep behavior disorder screening questionnaire: validation study of a Japanese version. Sleep Med. 2009;10(10):1151–4.

Wang Y, Wang ZW, Yang YC, Wu HJ, Zhao HY, Zhao ZX. Validation of the rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder screening questionnaire in China. Journal of clinical neuroscience : official journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia. 2015;22(9):1420–4.

You S, Moon HJ, Do SY, Wing YK, Sunwoo JS, Jung KY, Cho YW. The REM sleep behavior disorder screening questionnaire: validation study of the Korean version (RBDQ-KR). J Clin Sleep Med. 2017.

Li SX, Wing YK, Lam SP, Zhang J, Yu MW, Ho CK, Tsoh J, Mok V. Validation of a new REM sleep behavior disorder questionnaire (RBDQ-HK). Sleep Med. 2010;11(1):43–8.

Boeve BF, Molano JR, Ferman TJ, Lin SC, Bieniek K, Tippmann-Peikert M, Boot B, St Louis EK, Knopman DS, Petersen RC, et al. Validation of the Mayo sleep questionnaire to screen for REM sleep behavior disorder in a community-based sample. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9(5):475–80.

Boeve BF, Molano JR, Ferman TJ, Smith GE, Lin SC, Bieniek K, Haidar W, Tippmann-Peikert M, Knopman DS, Graff-Radford NR, et al. Validation of the Mayo sleep questionnaire to screen for REM sleep behavior disorder in an aging and dementia cohort. Sleep Med. 2011;12(5):445–53.

Frauscher B, Ehrmann L, Zamarian L, Auer F, Mitterling T, Gabelia D, Brandauer E, Delazer M, Poewe W, Hogl B. Validation of the Innsbruck REM sleep behavior disorder inventory. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society. 2012;27(13):1673–8.

Postuma RB, Arnulf I, Hogl B, Iranzo A, Miyamoto T, Dauvilliers Y, Oertel W, Ju YE, Puligheddu M, Jennum P, et al. A single-question screen for rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder: a multicenter validation study. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society. 2012;27(7):913–6.

Frauscher B, Iranzo A, Gaig C, Gschliesser V, Guaita M, Raffelseder V, Ehrmann L, Sola N, Salamero M, Tolosa E, et al. Normative EMG values during REM sleep for the diagnosis of REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep. 2012;35(6):835–47.

Kopecek M, Stepankova H, Lukavsky J, Ripova D, Nikolai T, Bezdicek O. Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA): normative data for old and very old Czech adults. Applied neuropsychology Adult. 2017;24(1):23–9.

Buskova J, Ibarburu V, Sonka K, Ruzicka E. Screening for REM sleep behavior disorder in the general population. Sleep Med. 2016;24:147.

Bland JM, Altman DG. Cronbach's alpha. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 1997;314(7080):572.

Boeve BF. Idiopathic REM sleep behaviour disorder in the development of Parkinson's disease. The Lancet Neurology. 2013;12(5):469–82.

Gagnon JF, Postuma RB, Mazza S, Doyon J, Montplaisir J. Rapid-eye-movement sleep behaviour disorder and neurodegenerative diseases. The Lancet Neurology. 2006;5(5):424–32.

Nomura T, Inoue Y, Kagimura T, Uemura Y, Nakashima K. Utility of the REM sleep behavior disorder screening questionnaire (RBDSQ) in Parkinson's disease patients. Sleep Med. 2011;12(7):711–3.

Frauscher B, Mitterling T, Bode A, Ehrmann L, Gabelia D, Biermayr M, Walters AS, Poewe W, Hogl B. A prospective questionnaire study in 100 healthy sleepers: non-bothersome forms of recognizable sleep disorders are still present. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10(6):623–9.

Mahlknecht P, Seppi K, Frauscher B, Kiechl S, Willeit J, Stockner H, Djamshidian A, Nocker M, Rastner V, Defrancesco M, et al. Probable RBD and association with neurodegenerative disease markers: a population-based study. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society. 2015;30(10):1417–21.

Acknowledgements

The authors greatly appreciate all subjects who volunteered to participate in the experiments described in this paper.

The permission to use the RBDSQ was obtained from Mapi Research Trust, Lyon, France. Internet: https://eprovide.mapi-trust.org.

Funding

Supported by Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic, grant nr. 16-28914A, Czech Science Foundation, GACR 16-07879S, project Nr. LO1611 and with financial support from the MEYS under NPU I program, by PROGRES Q35 and PROGRES Q27/LF1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JB - study design, funding, interpretations of results, manuscript preparation and revisions, data acquisition, PP and EM – data acquisition, manuscript revision, ER, PD and KS - funding, study design, interpretations of results, manuscript revisions, DK – statistical analysis, interpretations of results, final manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted according to the declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the General University Hospital in Prague. Written informed consent was obtained from all the patients and the healthy subjects for participation in the experiments.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Bušková, J., Peřinová, P., Miletínová, E. et al. Validation of the REM sleep behavior disorder screening questionnaire in the Czech population. BMC Neurol 19, 110 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-019-1340-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-019-1340-4