Abstract

Background

Aim to quantitatively analyze the clinical effectiveness for motor cortex stimulation (MCS) to refractory pain.

Methods

The literatures were systematically searched in database of Cocharane library, Embase and PubMed, using relevant strategies. Data were extracted from eligible articles and pooled as mean with standard deviation (SD). Comparative analysis was measured by non-parametric t test and linear regression model.

Results

The pooled effect estimate from 12 trials (n = 198) elucidated that MCS shown the positive effect on refractory pain, and the total percentage improvement was 35.2% in post-stroke pain and 46.5% in trigeminal neuropathic pain. There is no statistical differences between stroke involved thalamus or non-thalamus. The improvement of plexus avulsion (29.8%) and phantom pain (34.1%) was similar. The highest improvement rate was seen in post-radicular plexopathy (65.1%) and MCS may aggravate the pain induced by spinal cord injury, confirmed by small sample size. Concurrently, Both the duration of disease (r = 0.233, p = 0.019*) and the time of follow-up (r = 0.196, p = 0.016*) had small predicative value, while age (p = 0.125) had no correlation to post-operative pain relief.

Conclusions

MCS is conducive to the patients with refractory pain. The duration of disease and the time of follow-up can be regarded as predictive factor. Meanwhile, further studies are needed to reveal the mechanism of MCS and to reevaluate the cost-benefit aspect with better-designed clinical trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Refractory pain, resulting from various causes, presents a clinically therapeutic challenge as responding poorly to all types of available pharmacological therapies. With the development neuromodulatory techniques, intracranial and extracranial stimulation were seemed promising. Motor cortex stimulation (MCS) represents an effectively functional neurosurgery to attenuate the various types of neuropathic pain including post-stroke pain, trigeminal neuropathic pain, plexus, phantom pain, pain induced by spinal cord injury and post-radicular plexopathy [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. However, it remains controversial as some published articles shown negative results [6, 8,9,10]. The practical efficacy different in various centers and the small sample studies together contribute to the uncertain perspective of MCS. To solve the discrepancy, the aim of the present article is to quantitatively evaluate and analyze the clinical effectiveness for MCS to refractory pain.

Methods

Literature search

Correlated literatures were systematically retrieved from bibliographic databases, such as Google Scholar, Embase and PubMed, according to the predefined strategies including “motor cortex stimulation” and “pain”. Only literatures descripting the application of MCS in refractory pain were included for further analysis. Furthermore, grey literatures, lecture records and any missed trials were hand-searched.

Study selection

Only the literatures met the criteria below were retrieved and reviewed for eligibility:

-

1)

Participants: patients diagnosed with refractory pain;

-

2)

Interventions: extradural/subdural motor cortex stimulation (both of them shown the similar effect [11]); without any other surgical treatment;

-

3)

Outcomes: widely accepted and unified evaluation standard-Visual Analog Scale (VAS) was considered as primary outcome measure;

-

4)

Designs: clinical trials with restrict inclusion criteria; small sample studies (n < 5) would be removed because it may produce exaggerated intervention effect estimates;

-

5)

Predictive factors: systematical analysis of predictive factors.

Surgical management

Prior to the MCS operation, all patients underwent skin fiducial marker placement on standard anatomical reference points. The MCS operation was performed under general anesthesia through a small craniotomy over the motor cortex on the side contralateral to the pain. The motor cortex was identified through intraoperative somato-sensory evoked potentials (SSEP). Recording strip were epidurally placed perpendicular to and across the presumed location and direction of the central sulcus. The position was confirmed once the phase reversal was obtained [12]. The stimulation electrode (Medtronic 3587A/39585) was anatomically located in the motor cortical area parallel to the central sulcus. Co-registration of the preoperative and post-operative CT was used to confirmation localization of the electrode using the iElectrodes software (version 1.010) [13]. Eventually, the neurostimulator was permanently implanted subcutaneously in the chest after achieving satisfactory pain relief following temporal stimulation. Approximately 5–7 days after the implantation of the electrode, the stimulator is turned on, and the stimulation parameters depend on the patients’ subjective feelings to maximize the therapeutic effect and avoid side effects.

Statistical analysis

The data collected from the eligible studies was pooled and analyzed. Post-operative scores would be used to evaluate the efficacy of MCS for pain at short−/long-term period, comparing to the baseline. Changes in VAS scores were summarized for each time period for comparison and presented as mean with standard deviation (SD). To determine if efficacy was significantly different between the different types of neuropathic pain, normality test and homogeneity of variance test would be performed firstly. Then, data accorded with normal distribution and homogeneity of variance were compared by the Student’s t-test, otherwise, by non-parametric t test. Meanwhile, linear regression model would be used to investigate whether the age, duration of disease and time of follow-up could be regarded as predictive factors. All statistical analyses were performed in the Stata 12.0 software (StataCorp LP, College Station, USA), and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Search Results

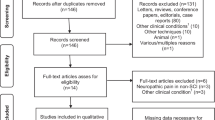

Overall, 2181 literatures initially identified in the databases (up to October 2017) with our search strategy. After independently reading the titles and abstracts of the relevant articles, 172 were included to further investigate. Full text of potentially relevant articles were independently retrieved by each review author, eventually, 12 [10, 11, 14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23] appeared to be eligible to apply MCS in refractory pain. The details of all included studies were demonstrated in Table 1, including the centers, the number of participants, diagnosis, duration of disease and the time of follow- up. Some literatures were excluded as they failed to fulfill our inclusion criteria: 1) without detail information of each patient [1, 3, 4, 24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]; VAS was not as the primary outcome measures [6, 9, 34,35,36]; small sample studies (participants less than 5) [37,38,39]. Moreover, there was the considerable confusion about the efficacy of MCS because four studies [6, 8,9,10] shown the invalid outcomes. Among included literatures, all reported the age of patients and the preoperative VAS scores [10, 11, 14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]; seven reported the duration of the disease [11, 16, 17, 19,20,21, 23]; and 9 reported the time of follow-up [10, 15,16,17, 19,20,21,22,23]. All the information used in the present study were available in the Additional file 1.

Clinical outcomes

We considered all patients with refractory pain who underwent MCS and were evaluated with VAS scores. Then, we investigated whether a significant difference existed among the different aetiologies of refractory pain. All subgroup data failed to pass the normality test (the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test or Shapiro-Wilk test depending on the sample size) and the homogeneity test of variance (Levene’s test). A non-parametric test (Wilcoxon signed-rank test) was used to investigate the analgesic effect of MCS. MCS showed a positive effect on refractory pain; the total percentage improvement was 35.2% for post-stroke pain and 46.5% for trigeminal neuropathic pain. For cases of cerebral infarction not located in the thalamus, the mean improvement was 47.3%, which was much higher than that of the cases of cerebral infarction located in the thalamus (40.6%). However, no significant differences were observed between strokes that involved the thalamus or non-thalamus (Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.700). The improvement of plexus avulsion (29.8%) and phantom pain (34.1%) was similar. The highest improvement rate was seen for post-radicular plexopathy (65.1%). However, MCS may aggravate the pain induced by spinal cord injury (− 3.5%) as confirmed by the small sample size (Fig. 1 & Additional file 2: Figure S1).

The detailed information of three patients with refractory pain underwent MCS were displayed in Table 2. And the neuroimaging data was shown in Fig. 2.

Outcomes predictors

A linear regression model (Pearson’s correlation) was used to determine whether age, the disease duration and the follow-up time had relationships with the percentage of improvement in the VAS. According to the outcome, the coefficient value (r) was 0.126* with a p value of 0.125 in the age subgroup. No significant relationship was observed between age and post-operative improvement. However, in the duration subgroup, the coefficient value was 0.233 with a p value of 0.019, and in the follow-up time subgroup, the coefficient value was 0.196 with a p value of 0.016. A small positive correlation was found among the duration, follow-up time and postoperative improvement (Fig. 3).

Discussion

Achievement

As reasonable medical therapy was invalid for patients with intractable pain, MCS emerged as a new and promising treatment option. After systematically collecting and quantifiably investigating data from numbers of relevant articles, it turned out that MCS performed effective effect on refractory pain. The highest improvement rate was seen for post-radicular plexopathy (65.1%), although and MCS might aggravate the pain induced by a spinal cord injury. However, the small sample size was a limitation to draw these conclusions. The mean improvement of pain resulting from stroke was 35.2%, and there no significant differences were found among the stroke subgroups (total, lesion involving the thalamus and lesion outside the thalamus). The mechanism of post-stroke pain is widely accepted to be a complex process of network reorganization rather than a simple process of focal hyperexcitability or disinhibition [40]. MCS effectively attenuates pain by directly affecting activity in the somatosensory areas and thalamic nuclei and inhibiting spinal primary afferents and spinothalamic tract neurons [2]. Moreover, MCS takes part in modulation of a deeper and wider range of brain structures, such as the striatum, thalamic area, cerebellum, ventral posterolateral nucleus (VPL) and rostral agranular insular cortex (RAIC) [41, 42]. Patients with trigeminal neuropathic pain obtained 46.5% pain relief at the last follow-up. The explanations for the outcomes may be related to the facial area, which is one of the largest regions of the motor cortex [43]. The improvement rates of plexus avulsion and phantom pain were similar. This phenomenon may result from the same pathophysiological changes in both aetiologies: (i) altered activity in the neuromas after injury; ephaptic connections are formed after injuries in the periphery, which may result in increased afferent signaling, and increases in new connections may lower the threshold [44]; (ii) spinal segmental deafferentation [45]; and (iii) cortical reorganization of sensory fields [46, 47].

Meanwhile, both the duration of disease and the time of follow-up had small predicative value, while age had no correlation to post-operative VAS, which was rarely reported in previous articles. According to the existing literature, in response to operative repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) or a pharmaceutical drug, the relatively intact cortico-spinal tract and the sensory system, experience pain relief in the first month, and motor weakness of the painful area are the predictors [48,49,50,51]. However, approximately about 30% of patients who did not show improvement by rTMS were improved by MCS [52], which might raise concerns for many clinicians regarding the cost-effectiveness ratio of this method due to the low negative predictive value. Regardless, preoperative rTMS is worth using. On one hand, the analgesic effects of preoperative rTMS may help clinicians predict a patient’s prognosis and increase the confidence of neurosurgeons performing MCS. On the other hand, the clinical effects of MCS are estimated not only by single predictors of the response to rTMS but also by a combination of other factors, including the different pain subtypes, duration, hyperpathia, and preoperative motor status. Therefore, preoperative rTMS is valuable. The explanation for the positive predictive value of rTMS is that the descending volleys elicited by epidural MCS are similar to those elicited by rTMS to produce analgesic effects [53, 54]. Direct wave (D-wave) and indirect waves (I-waves) are widely accepted as a mechanism of electrical stimulation of the brain cortex. The D-wave is the first valley resulting from direct stimulation of pyramidal tract axons and I-waves are the later volleys resulting from synaptic activation of the same pyramidal tract neurons. In addition, the morphology of pyramidal neurons in layer 5 of the motor cortex is crucial for generate of I-waves [54]. Generation of descending volleys depends on the electrode placement, montage, polarity and stimulus intensity. Bipolar MCS was confirmed to generate I3-waves capable of producing maximal pain relief, and the analgesic effects of MCS were related to activation of intracortical horizontal fibers or interneurons rather than the pyramidal tract [55].

The concrete mechanism of MCS remains elusive. Nevertheless, it was hypothesized that the potential mechanism might be correlated with several factors. Brasil-Neto and his colleagues considered that the corollary discharge reinforcement could deteriorate sensory feedback [56]. Increase of regional cerebral blood flow in the ipsilateral ventrolateral thalamus cingulate gyrus, orbitofrontal cortex, and brainstem may help to explain the mechanism of MCS [57, 58]. Besides, the activation of top-down controls related to the excitation of intracortical horizontal fibers [58] and perigenual cingulate and orbitofrontal areas may modulate the emotional appraisal of pain [59]. In Silva’s opinion, spinal anti-neuroinflammatory effect and the activation of the cannabinoid and opioid systems via descending inhibitory pathways [60]. Moreover, the basic researches also helped interpret the secret of MCS. The present treatment helped alleviate the level of glial acidic protein (GAP) in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) [61] and opioid and dopamine D1 receptors within the PAG participated the inhibitory effect of MCS [59, 62].

Considering the stimulation of anatomical region, it had been confirmed that stimulation of cortical regions adjacent to the primary motor cortex fail to produce similar analgesic effects [58], which was highlighted by Hosomi et,al, he agreed with the stimulation of central sulcus was more effectively than the precentral gyrus [63]. Also, subdural MCS provided similar therapeutic effect compared to the preferred extradural MCS in long-term follow-up studies [11, 18]. These together indicated that effective cortical region of MCS was very limited though the neuromodulatory process involve various brain region. The correct electrodes placement was important.

Obviously, MCS represents an effectively functional neurosurgery to attenuate the medically intractable pain symptom [11]. Modulation of MCS not only had analgesic effects but improvement in motor and sensory system [38]; (4) MCS could restore tactile and thermal sensory loss to some extent [64]. However, the advantages should not be highlighted excessively and the side effects need to focus on. According to a case report, patient with stroke underwent MCS experienced the supernumerary phantom arm [65]. Seizure related the abrupt increase in stimulation intensity, infection, postsurgical incisional pain, and transient cerebral edema were not uncommon but tolerable [11, 66]. Intensive reprogramming can recapture the benefit of MCS, with increased risk of seizures [67].

Concurrently, past decades witnessed significant breakthrough in this field. An increasing researches focused more on the preoperative rTMS as the auxiliary treatment possessed predictive value to access efficacy of MCS, especially the 20 Hz rTMS significantly ameliorated the pain [68, 69]. Ivanishvili et al. initially pointed out that the cyclization of MCS will improve pain relief as well as prolong battery life and delay the replacement [36]. Clinically, MCS could be considered as add-on therapy when patients with pain failure to response to the spinal cord stimulation (SCS). If patients were failed to the MCS, ziconotide intrathecal delivery represented the alternative therapy [70]. As opioid-receptor availability appears to be related to the efficacy of MCS, optogenetics-mediated MCS may help clinicians to select the candidates most likely to benefit from this procedure [71].

With the progression of science and technology, modern devices and medicine image post-processing technology contributed to the interpretation of the mechanism. The appearance of fMRI imaging helps precisely locate facial areas on the precentral gyrus and contributes to pain reduction [66]. According to the changes in cerebral flood flow (CBF) evaluated by positron emission tomography (PET), we could verify the participation of motor and premotor cortices, anterior cingulate and PAG to modulate chronic pain [29, 72]. Moreover, intraoperative motor evoked potentials (iMEPs) recording had predictive value and cathode generated best analgesic effect [73] and repetitive laser stimulation (RLS)-induced gamma-band oscillations (GBO) modulation could detect cortical pain process in unresponsive wakefulness syndrome [74].

Limitations

Though we tried our best to retrieve all published articles, establish strict included criteria, choose the optimal statistical methods, the small sample and the poor design studies still influenced the reliability of our article. Well-designed studies, such as randomized controlled or randomized, double-blind, crossover studies, were expected to further verify the effectiveness of MCS. Also, we failed to eliminate the negative effect brought by the different stimulation parameters across centers. The individual stimulation parameters rendered the statistical work difficult.

Applications and future work

Although the rapid development of the MCS, it was still unclear whether the therapy represents an advancing alternative treatment. Besides, the specified mechanism and limitations await further refinement. Lastly, the efficacy of MCS depends on the accurate electrode placement, individualized programming parameters, patient selections, and response to rTMS. Future work is needed to further illustrate the advancing treatment and potential mechanism, such as endogenous pain control, the interaction between motor and pain system [75], and the involved neural circuits [20]. New generation of stimulators and electrode design worth paying enough attention to. The optimal target should be evaluated preoperatively via the usage of advanced neurological functional and structural imaging. General, specialized, quantitative and objective evaluation criterion should be developed and adopted to accurately investigate the pain relief in the clinical trials. Even better would be to focus more on the quality of life and capacity for work of patients. Well-designed study can provide strong evidence to explain this question. Future researches about the comparisons and contrasts between MCS and other neuromodulatory techniques is expected. Also, based on the principle of patient first, in order to minimize patient trauma, invasive treatments could be replaced by revolutionary and promising non-invasive therapies, if there is no statistically significant different in cost-benefit aspect.

Conclusion

MCS is conducive to the patients with refractory pain. The duration of disease and the time of follow-up can be regarded as predictive factor. Meanwhile, further studies are needed to reveal the mechanism of MCS and to reevaluate the cost-benefit aspect with better-designed clinical trials.

Abbreviations

- ACC:

-

Anterior cingulate cortex

- CBF:

-

Cerebral flood

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- fMRI:

-

functional MRI

- FU:

-

Follow up

- GAP:

-

Glial acidic protein

- GBO:

-

Gamma-Band Oscillations

- iMEPs:

-

intraoperative Motor Evoked Potentials

- MCS:

-

Motor cortex stimulation

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NA:

-

Not available

- PAG:

-

Periaqueductal gray

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- RAIC:

-

Rostral Agranular Insular Cortex

- RLS:

-

Repetitive laser stimulation

- rTMS:

-

repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation

- SCS:

-

Spinal cord stimulation

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- VAS:

-

Visual analogue scale

- VPL:

-

Ventral posterolateral nucleus

References

Fontaine D, Hamani C, Lozano A. Efficacy and safety of motor cortex stimulation for chronic neuropathic pain: critical review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 2009;110(2):251–6.

Canavero S, Bonicalzi V. Extradural cortical stimulation for central pain. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2007;97(Pt 2):27–36.

Fagundes-Pereyra WJ, Teixeira MJ, Reyns N, Touzet G, Dantas S, Laureau E, Blond S. Motor cortex electric stimulation for the treatment of neuropathic pain. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2010;68(6):923–9.

Carroll D, Joint C, Maartens N, Shlugman D, Stein J, Aziz TZ. Motor cortex stimulation for chronic neuropathic pain: a preliminary study of 10 cases. Pain. 2000;84(2–3):431–7.

Arle JE, Shils JL. Motor cortex stimulation for pain and movement disorders. Neurotherapeutics. 2008;5(1):37–49.

Fujii M, Ohmoto Y, Kitahara T, Sugiyama S, Uesugi S, Yamashita T, Shiroyama Y, Ito H. Motor cortex stimulation therapy in patients with thalamic pain. No Shinkei Geka. 1997;25(4):315–9.

Rahimpour S, Lad SP. Surgical options for atypical facial pain syndromes. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2016;27(3):365–70.

Cioni B, Meglio M. Motor cortex stimulation for chronic non-malignant pain: current state and future prospects. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2007;97(Pt 2):45–9.

Radic JA, Beauprie I, Chiasson P, Kiss ZH, Brownstone RM. Motor cortex stimulation for neuropathic pain: a randomized cross-over trial. Can J Neurol Sci. 2015;42(6):401–9.

Sachs AJ, Babu H, Su YF, Miller KJ, Henderson JM. Lack of efficacy of motor cortex stimulation for the treatment of neuropathic pain in 14 patients. Neuromodulation. 2014;17(4):303–10 discussion 310-301.

Delavallee M, Abu-Serieh B, de Tourchaninoff M, Raftopoulos C. Subdural motor cortex stimulation for central and peripheral neuropathic pain: a long-term follow-up study in a series of eight patients. Neurosurgery. 2008;63(1):101–5 discussion 105-108.

Nguyen JP, Lefaucheur JP, Decq P, Uchiyama T, Carpentier A, Fontaine D, Brugières P, Pollin B, Fève A, Rostaing S, et al. Chronic motor cortex stimulation in the treatment of central and neuropathic pain. Correlations between clinical, electrophysiological and anatomical data. Pain. 1999;82(3):245–51.

Blenkmann AO, Phillips HN, Princich JP, Rowe JB, Bekinschtein TA, Muravchik CH, Kochen S. iElectrodes: a comprehensive open-source toolbox for depth and subdural grid electrode localization. Front Neuroinform. 2017;11:14.

Brown JA, Pilitsis JG. Motor cortex stimulation for central and neuropathic facial pain: a prospective study of 10 patients and observations of enhanced sensory and motor function during stimulation. Neurosurgery. 2005;56(2):290–7 discussion 290-297.

Pirotte B, Voordecker P, Neugroschl C, Baleriaux D, Wikler D, Metens T, Denolin V, Joffroy A, Massager N, Brotchi J, et al. Combination of functional magnetic resonance imaging-guided neuronavigation and intraoperative cortical brain mapping improves targeting of motor cortex stimulation in neuropathic pain. Neurosurgery. 2005;56(2 Suppl):344–59 discussion 344-359.

Rasche D, Ruppolt M, Stippich C, Unterberg A, Tronnier VM. Motor cortex stimulation for long-term relief of chronic neuropathic pain: a 10 year experience. Pain. 2006;121(1–2):43–52.

Velasco F, Arguelles C, Carrillo-Ruiz JD, Castro G, Velasco AL, Jimenez F, Velasco M. Efficacy of motor cortex stimulation in the treatment of neuropathic pain: a randomized double-blind trial. J Neurosurg. 2008;108(4):698–706.

Buchanan RJ, Darrow D, Monsivais D, Nadasdy Z, Gjini K. Motor cortex stimulation for neuropathic pain syndromes: a case series experience. Neuroreport. 2014;25(9):715–7.

Delavallee M, Finet P, de Tourtchaninoff M, Raftopoulos C. Subdural motor cortex stimulation: feasibility, efficacy and security on a series of 18 consecutive cases with a follow-up of at least 3 years. Acta Neurochir. 2014;156(12):2289–94.

Slotty PJ, Eisner W, Honey CR, Wille C, Vesper J. Long-term follow-up of motor cortex stimulation for neuropathic pain in 23 patients. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2015;93(3):199–205.

Sokal P, Harat M, Zielinski P, Furtak J, Paczkowski D, Rusinek M. Motor cortex stimulation in patients with chronic central pain. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2015;24(2):289–96.

Rasche D, Tronnier V. Clinical significance of invasive motor cortex stimulation for trigeminal facial neuropathic pain syndromes. Neurosurgery. 2016;79(5):655–66.

Zhang X, Hu Y, Tao W, Zhu H, Xiao D, Li Y. The effect of motor cortex stimulation on central Poststroke pain in a series of 16 patients with a mean follow-up of 28 months. Neuromodulation. 2017;20(5):492–6.

Tsubokawa T, Katayama Y, Yamamoto T, Hirayama T, Koyama S. Chronic motor cortex stimulation for the treatment of central pain. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 1991;52:137–9.

Hosobuchi Y. Motor cortical stimulation for control of central deafferentation pain. Adv Neurol. 1993;63:215–7.

Tsubokawa T, Katayama Y, Yamamoto T, Hirayama T, Koyama S. Chronic motor cortex stimulation in patients with thalamic pain. J Neurosurg. 1993;78(3):393–401.

Ebel H, Rust D, Tronnier V, Boker D, Kunze S. Chronic precentral stimulation in trigeminal neuropathic pain. Acta Neurochir. 1996;138(11):1300–6.

Nguyen JP, Keravel Y, Feve A, Uchiyama T, Cesaro P, Le Guerinel C, Pollin B. Treatment of deafferentation pain by chronic stimulation of the motor cortex: report of a series of 20 cases. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 1997;68:54–60.

Garcia-Larrea L, Peyron R, Mertens P, Gregoire MC, Lavenne F, Le Bars D, Convers P, Mauguiere F, Sindou M, Laurent B. Electrical stimulation of motor cortex for pain control: a combined PET-scan and electrophysiological study. Pain. 1999;83(2):259–73.

Nguyen JP, Lefaucher JP, Le Guerinel C, Eizenbaum JF, Nakano N, Carpentier A, Brugieres P, Pollin B, Rostaing S, Keravel Y. Motor cortex stimulation in the treatment of central and neuropathic pain. Arch Med Res. 2000;31(3):263–5.

Saitoh Y, Shibata M, Hirano S, Hirata M, Mashimo T, Yoshimine T. Motor cortex stimulation for central and peripheral deafferentation pain. Report of eight cases. J Neurosurg. 2000;92(1):150–5.

Saitoh Y, Hirano S, Kato A, Kishima H, Hirata M, Yamamoto K, Yoshimine T. Motor cortex stimulation for deafferentation pain. Neurosurg Focus. 2001;11(3):E1.

Nguyen JP, Velasco F, Brugieres P, Velasco M, Keravel Y, Boleaga B, Brito F, Lefaucheur JP. Treatment of chronic neuropathic pain by motor cortex stimulation: results of a bicentric controlled crossover trial. Brain Stimul. 2008;1(2):89–96.

Im SH, Ha SW, Kim DR, Son BC. Long-term results of motor cortex stimulation in the treatment of chronic, intractable neuropathic pain. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2015;93(3):212–8.

Isagulyan ED, Tomsky AA, Dekopov AV, Salova EM, Troshina EM, Dorokhov EV, Shabalov VA. Results of motor cortex stimulation in the treatment of chronic pain syndromes. Zh Vopr Neirokhir Im N N Burdenko. 2015;79(6):46–60.

Kolodziej MA, Hellwig D, Nimsky C, Benes L. Treatment of central Deafferentation and trigeminal neuropathic pain by motor cortex stimulation: report of a series of 20 patients. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg. 2016;77(1):52–8.

Ito M, Kuroda S, Takano K, Maruichi K, Chiba Y, Morimoto Y, Iwasaki Y. Motor cortex stimulation for post-stroke pain using neuronavigation and evoked potentials: report of 3 cases. No Shinkei Geka. 2006;34(9):919–24.

Fonoff ET, Hamani C, Ciampi de Andrade D, Yeng LT, Marcolin MA, Jacobsen Teixeira M. Pain relief and functional recovery in patients with complex regional pain syndrome after motor cortex stimulation. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2011;89(3):167–72.

Louppe JM, Nguyen JP, Robert R, Buffenoir K, de Chauvigny E, Riant T, Pereon Y, Labat JJ, Nizard J. Motor cortex stimulation in refractory pelvic and perineal pain: report of two successful cases. Neurourol Urodyn. 2013;32(1):53–7.

Hosomi K, Seymour B, Saitoh Y. Modulating the pain network--neurostimulation for central poststroke pain. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11(5):290–9.

Jung HH, Shin J. Rostral Agranular insular cortex lesion with motor cortex stimulation enhances pain modulation effect on neuropathic pain model. Neural Plast. 2016;2016:3898924.

Kim J, Ryu SB, Lee SE, Shin J, Jung HH, Kim SJ, Kim KH, Chang JW. Motor cortex stimulation and neuropathic pain: how does motor cortex stimulation affect pain-signaling pathways? J Neurosurg. 2016;124(3):866–76.

Schley M, Wilms P, Toepfner S, Schaller H, Schmelz M, Konrad C, Birbaumer N. Painful and nonpainful phantom and stump sensations in acute traumatic amputees. J Trauma. 2008;65(4):858–64.

Mackenzie N. Phantom limb pain during spinal anaesthesia. Recurrence in amputees. Anaesthesia. 2010;38(9):886–7.

Flor H, Elbert T, Knecht S, Wienbruch C, Pantev C, Birbaumers N, Larbig W, Taub E. Phantom-limb pain as a perceptual correlate of cortical reorganization following arm amputation. Nature. 1995;375(6531):482–4.

Karl A. Neuroelectric source imaging of steady-state movement-related cortical potentials in human upper extremity amputees with and without phantom limb pain. Pain. 2004;110(1):90–102.

Andréobadia N, Mertens P, Lelekovboissard T, Afif A, Magnin M, Garcialarrea L. Is life better after motor cortex stimulation for pain control? Results at long-term and their prediction by preoperative rTMS. Pain Physician. 2014;17(1):53–62.

Katayama Y, Fukaya C, Yamamoto T. Poststroke pain control by chronic motor cortex stimulation: neurological characteristics predicting a favorable response. J Neurosurg. 1998;89(4):585–91.

Nuti C, Peyron R, Garcia-Larrea L, Brunon J, Laurent B, Sindou M, Mertens P. Motor cortex stimulation for refractory neuropathic pain: four year outcome and predictors of efficacy. Pain. 2005;118(1–2):43–52.

Koppelstaetter F, Siedentopf CM, Rhomberg P, Lechner-Steinleitner S, Mottaghy FM, Eisner W, Golaszewski SM. Functional magnetic resonance imaging before motor cortex stimulation for phantom limb pain. Nervenarzt. 2007;78(12):1435–9.

Maarrawi J, Peyron R, Mertens P, Costes N, Magnin M, Sindou M, Laurent B, Garcia-Larrea L. Brain opioid receptor density predicts motor cortex stimulation efficacy for chronic pain. Pain. 2013;154(11):2563–8.

Lefaucheur JP, Ménard-Lefaucheur I, Goujon C, Keravel Y, Nguyen JP. Predictive value of rTMS in the identification of responders to epidural motor cortex stimulation therapy for pain. J Pain. 2011;12(10):1102–11.

Di LV, Oliviero A, Profice P, Meglio M, Cioni B, Tonali P, Rothwell JC. Descending spinal cord volleys evoked by transcranial magnetic and electrical stimulation of the motor cortex leg area in conscious humans. J Physiol. 2010;537(3):1047–58.

Lefaucheur JP, Holsheimer J, Goujon C, Keravel Y, Nguyen JP. Descending volleys generated by efficacious epidural motor cortex stimulation in patients with chronic neuropathic pain. Exp Neurol. 2010;223(2):609–14.

Holsheimer J, Nguyen JP, Lefaucheur JP, Manola L. Cathodal, anodal or bifocal stimulation of the motor cortex in the management of chronic pain? Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2007;97(Pt 2):57–66.

Brasil-Neto JP. Motor cortex stimulation for pain relief: do corollary discharges play a role? Front Hum Neurosci. 2016;10:323.

Brown JA. Motor cortex stimulation. Neurosurg Focus. 2001;11(3):E5.

DosSantos MF, Ferreira N, Toback RL, Carvalho AC, DaSilva AF. Potential mechanisms supporting the value of motor cortex stimulation to treat chronic pain syndromes. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:18.

Garcia-Larrea L, Peyron R. Motor cortex stimulation for neuropathic pain: from phenomenology to mechanisms. NeuroImage. 2007;37(Suppl 1):S71–9.

Silva GD, Lopes PS, Fonoff ET, Pagano RL. The spinal anti-inflammatory mechanism of motor cortex stimulation: cause of success and refractoriness in neuropathic pain? J Neuroinflammation. 2015;12:10.

O'Brien AT, Amorim R, Rushmore RJ, Eden U, Afifi L, Dipietro L, Wagner T, Valero-Cabre A. Motor cortex Neurostimulation Technologies for Chronic Post-stroke Pain: implications of tissue damage on stimulation currents. Front Hum Neurosci. 2016;10:545.

Chiou RJ, Chang CW, Kuo CC. Involvement of the periaqueductal gray in the effect of motor cortex stimulation. Brain Res. 2013;1500:28–35.

Hosomi K, Saitoh Y, Kishima H, Oshino S, Hirata M, Tani N, Shimokawa T, Yoshimine T. Electrical stimulation of primary motor cortex within the central sulcus for intractable neuropathic pain. Clin Neurophysiol. 2008;119(5):993–1001.

Fontaine D, Bruneto JL, El Fakir H, Paquis P, Lanteri-Minet M. Short-term restoration of facial sensory loss by motor cortex stimulation in peripheral post-traumatic neuropathic pain. J Headache Pain. 2009;10(3):203–6.

Canavero S, Bonicalzi V, Castellano G, Perozzo P, Massa-Micon B. Painful supernumerary phantom arm following motor cortex stimulation for central poststroke pain. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1999;91(1):121–3.

Esfahani DR, Pisansky MT, Dafer RM, Anderson DE. Motor cortex stimulation: functional magnetic resonance imaging-localized treatment for three sources of intractable facial pain. J Neurosurg. 2011;114(1):189–95.

Henderson JM, Boongird A, Rosenow JM, LaPresto E, Rezai AR. Recovery of pain control by intensive reprogramming after loss of benefit from motor cortex stimulation for neuropathic pain. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2004;82(5–6):207–13.

Andre-Obadia N, Peyron R, Mertens P, Mauguiere F, Laurent B, Garcia-Larrea L. Transcranial magnetic stimulation for pain control. Double-blind study of different frequencies against placebo, and correlation with motor cortex stimulation efficacy. Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;117(7):1536–44.

Houze B, Bradley C, Magnin M, Garcia-Larrea L. Changes in sensory hand representation and pain thresholds induced by motor cortex stimulation in humans. Cereb Cortex. 2013;23(11):2667–76.

Voirin J, Darie I, Fischer D, Simon A, Rohmer-Heitz I, Proust F. Ziconotide intrathecal delivery as treatment for secondary therapeutic failure of motor cortex stimulation after 6 years. Neural Plasticity. 2016;62(5):284–8.

Liu S, Tao F. Application of optogenetics-mediated motor cortex stimulation in the treatment of chronic neuropathic pain. J Transl Sci. 2016;2(5):286–8.

Garcia-Larrea L, Peyron R, Mertens P, Gregoire MC, Lavenne F, Bonnefoi F, Mauguiere F, Laurent B, Sindou M. Positron emission tomography during motor cortex stimulation for pain control. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 1997;68(1–4 Pt 1):141–8.

Holsheimer J, Lefaucheur JP, Buitenweg JR, Goujon C, Nineb A, Nguyen JP. The role of intra-operative motor evoked potentials in the optimization of chronic cortical stimulation for the treatment of neuropathic pain. Clin Neurophysiol. 2007;118(10):2287–96.

Naro A, Leo A, Cannavo A, Buda A, Bramanti P, Calabro RS. Do unresponsive wakefulness syndrome patients feel pain? Role of laser-evoked potential-induced gamma-band oscillations in detecting cortical pain processing. Neuroscience. 2016;317:141–8.

Farina S, Tinazzi M, Le Pera D, Valeriani M. Pain-related modulation of the human motor cortex. Neurol Res. 2003;25(2):130–42.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all patients, researchers, and institutions for their collaboration and contribution to this study.

Funding

This work was supported by Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals Clinical Medicine Development of Special Funding (No. XM201304), Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission (Z161100000216130) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81701276, 81471327).

Availability of data and materials

All data have been presented within the manuscript and Additional file 1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KZ contributed to the design of the study and wrote the manuscript. JJM and WHH contributed to data analysis and wrote the manuscript. CZ and XW contributed the data analysis and to modify the article. CL, BTZ and JJZ contributed to the data collection and data interpretation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Raw data. Brief description of the data: Raw data from each included article (XLSX 20 kb)

Additional file 2:

Figure S1. Analysis of the aetiology and prognosis of pain. KS: Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; SW: Shapiro-Wilk test. (TIF 1671 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Mo, JJ., Hu, WH., Zhang, C. et al. Motor cortex stimulation: a systematic literature-based analysis of effectiveness and case series experience. BMC Neurol 19, 48 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-019-1273-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-019-1273-y