Abstract

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is the leading cause of kidney failure worldwide. Mortality and morbidity associated with DKD are increasing with the global prevalence of type 2 diabetes. Chronic, sub-clinical, non-resolving inflammation contributes to the pathophysiology of renal and cardiovascular disease associated with diabetes. Inflammatory biomarkers correlate with poor renal outcomes and mortality in patients with DKD. Targeting chronic inflammation may therefore offer a route to novel therapeutics for DKD. However, the DKD patient population is highly heterogeneous, with varying etiology, presentation and disease progression. This heterogeneity is a challenge for clinical trials of novel anti-inflammatory therapies. Here, we present a conceptual model of how chronic inflammation affects kidney function in five compartments: immune cell recruitment and activation; filtration; resorption and secretion; extracellular matrix regulation; and perfusion. We believe that the rigorous alignment of pathophysiological insights, appropriate animal models and pathology-specific biomarkers may facilitate a mechanism-based shift from recruiting ‘all comers’ with DKD to stratification of patients based on the principal compartments of inflammatory disease activity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Risk factors, such as genetic predisposition, sedentary lifestyle, overweight and unhealthy diet, have resulted in an unprecedented prevalence of type 2 diabetes [1]. Consequently, kidney disease secondary to diabetes (diabetic kidney disease, DKD) has become the leading cause of kidney failure, with more than 400 000 deaths among adults worldwide in 2017 [2, 3]. However, clinical presentation and end organ damage vary widely among patients with type 2 diabetes, with around one in three patients developing DKD with albuminuria > 300 mg/day and/or glomerular filtration rate (GFR) < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 [3].

The identification of molecular pathways connecting systemic and local inflammation to the pathology of type 2 diabetes and DKD has sparked growing interest in targeting inflammation to prevent disease progression, as well as improving patient risk stratification by inflammatory biomarkers. Sub-clinical chronic inflammation with multi-organ crosstalk is increasingly recognized as a driver of linked cardiovascular, renal and metabolic disease states [4,5,6,7].

Overt immune cell infiltration was not historically considered as one of the classical histopathological signs of DKD: glomerular sclerosis and mesangial expansion, first noted in the 1930s, accompanied by thickening of glomerular and tubular basement membranes, podocyte injury and tubulointerstitial fibrosis [8,9,10]. However, inflammatory biomarkers correlate with mortality and end-stage renal disease in patients with DKD [5]. Kidney failure, furthermore, causes systemic inflammation that contribute to morbidity and mortality among patients with chronic kidney disease [6]. Only since the discovery of macrophage infiltration as a key histopathological feature in the 1990s has it become recognized that fibrosis and sclerosis in the diabetic kidney are part of a chronic inflammatory disease process that correlates with disease progression [11,12,13,14,15]. Inflammation may therefore represent a key factor in development of DKD for a substantial subgroup of patients with type 2 diabetes.

The complex and heterogeneous pathophysiology of DKD presents serious challenges to the development of effective treatments [16, 17]. Chronic kidney disease in a patient with type 2 diabetes may be a direct result of diabetes, exacerbated by diabetes or unrelated to diabetes [18, 19]. At present, these disease states can only be differentiated by histological analysis of kidney biopsies [18, 19]. Although classifications of DKD have been proposed [20], the lack of consistent use of biopsies as a diagnostic tool in diabetic patients with proteinuria calls into question the general translatability of observations in cohorts of patients who have undergone biopsy to the general diabetic population. Examples of the diverse histopathology of DKD are shown in Fig. 1.

Histology showing the complex and heterogeneous glomerular pathology in DKD. A: Minimal to mild glomerular pathology with mild mesangial expansion; Tervaert class I–IIa [20]. B: Severe mesangial expansion and hypercellularity; Tervaert class IIb. C: Ischaemic phenotype with collapse of glomerular segments, segmental sclerosis and mild mesangial expansion; Tervaert class IIa. D: Severe mesangial expansion, Kimmelstiel-Wilson nodule without mesangiolysis; Tervaert class III. E: Hyperfiltrating phenotype with enlarged glomerular tuft, perihilar capsular adhesion and severe mesangial expansion; Tervaert class IIb. F: Mild mesangial expansion, Kimmelstiel-Wilson nodule with mesangiolysis; Tervaert class III

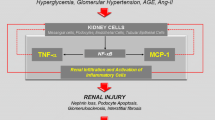

Multiple molecular pathways contribute to the chronic, sub-clinical, non-resolving inflammation that characterizes DKD in many patients (Table 1) [21,22,23]. Kidney cell injury or stress leads to release of damage-associated molecular patterns that activate pro-inflammatory intracellular signaling pathways [24]. Noxious biochemical stimuli resulting from high plasma glucose and lipid levels include oxidative stress, reactive oxygen species, glycated proteins, and oxidized lipids [23, 25]. In addition, glycated proteins can directly activate the complement system and initiate pro-inflammatory signaling [21,22,23]. High capillary blood pressure places potentially damaging high shear forces on cells, and these are exacerbated by stiffness due to fibrosis [26]. In response to ongoing activation of innate immune damage sensors, kidney endothelial cells, mesangial cells and podocytes produce multiple inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and adhesion molecules. These activate and recruit monocytes and macrophages, leading to further cascading inflammatory responses [23, 27]. The ongoing chronic inflammation results in extracellular matrix deposition and fibrosis, driven both by kidney-resident cells and by recruited cells of the innate immune system [28].

Several biomarker studies indicate that inflammation predicts and precedes development of albuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetes or DKD [30,31,32,33,34,35]. Still, clinical trials of novel anti-inflammatory therapies in patients with DKD have not demonstrated consistent benefit on renal outcomes, despite improvements in biomarker outcomes (as reviewed in detail below) [36,37,38]. The renal side effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, for example, preclude their use in patients with DKD, and may stem partly from their effects on renal prostaglandin signaling [39]. A better understanding of how a chronic inflammatory microenvironment drives the development and progression of DKD may unlock the potential of anti-inflammatory therapy, by allowing segmentation of patients according to their specific inflammatory activity.

Five-compartment model of diabetic kidney disease immunopathology

To conceptualize the complex immunopathology of the kidney during diabetes, we highlight five key compartments of kidney function and structure that are impaired by chronic inflammatory disease activity (Fig. 2). The five compartments are not mutually exclusive, and their relative importance may vary among patients. We show how the model can help to align pre-clinical models for target validation with clinical efficacy endpoints and patient selection criteria. Stratifying patients with DKD based on their predominant immunopathology could enable testing of novel anti-inflammatory drugs in the patients most likely to benefit. As discussed in the section on clinical trial design, this approach would currently require kidney biopsy, but may in future be based on circulatory, urinary or imaging biomarkers [34, 40, 41].

Five-compartment model of impairment due to chronic inflammation in diabetic kidney disease. Conceptual model of five functional and structural compartments that can be affected by immunopathology in patients with diabetic kidney disease. The model provides a framework for linking pre-clinical models of disease pathways with predominant immunopathology in particular patient types. Stratification of patients based on predominant immunopathology in the five-compartment model may enable targeting of the right treatments to the right patients

Immune cell recruitment and activation

During stress or inflammation, such as those triggered by hypoxia, ATP or other damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) in the DKD microenvironment, can result in kidney cells expressing chemokines and adhesion molecules. Together this attracts circulating leukocytes into the damaged renal tissue and activates resident cells [23, 42].

Glomerular endothelial cells, mesangial cells, podocytes and tubular epithelial cells express multiple cytokines, including the interleukin (IL) family members (e.g. IL-1, IL-6 and IL-19) tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α); multiple chemokines, including C–C motif ligand 2 (CCL2); and multiple adhesion molecules, including vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1), intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) and selectins (Table 1) [27]. Activated monocytes/macrophages recruited into the kidney amplify the response by producing pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-18) [22]. Activated immune cells also produce multiple molecules that can cause further renal injury, including metalloproteases, reactive oxygen species, advanced glycation end-products and complement proteins [22, 43, 44].

Recruitment of monocytes and macrophages into the kidney is a key step in the pathophysiology of DKD [22]. Macrophage accumulation in the kidney correlates strongly with serum creatinine levels, interstitial myofibroblast accumulation and interstitial fibrosis scores [12, 14, 15]. Resident macrophages and dendritic cells in the tubulointerstitium also contribute to disease progression by recruiting and activating lymphocytes [45]. Non-classical renal ‘patrolling’ monocytes may further orchestrate immune cell responses at the glomerular vascular interface, including recruitment and activation of neutrophils [46, 47]. Interestingly, cell-to-cell communication of resident immune cells, such as macrophages, with renal cells has also been shown to regulate transendothelial transport of immune complexes, as well as other immunoregulatory pathways [23, 48].

Macrophages may progress from the M1-like pro-inflammatory phase to the M2-like tissue repair stage, however, both forms coexist during chronic inflammation in DKD and represent a spectrum of macrophage phenotypes, leading to fibrosis [21]. Pro-fibrotic mediators released by macrophages induce extracellular matrix deposition, leading to fibrosis and impaired renal function [10, 49].

Filtration

In the early stages of DKD, glomerular hyperfiltration may cause kidney injury and contribute to disease progression by increasing physical stress and oxygen demand to drive reabsorption [29, 50]. Current standard of care, inhibition of the renin angiotensin aldosterone system and sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 (SGLT2), is reducing glomerular injury and can provide significant clinical benefit for patients [29, 50, 51]. However, isolated glomerular hyperfiltration does not predict development of advanced DKD, consistent with a pathophysiological role for chronic inflammation [51].

Chronic inflammation adversely affects all three components of the glomerular filter: the fenestrated endothelium, the basement membrane and the epithelium, comprising podocytes and slit diaphragms (Fig. 3) [52]. TNF-α secreted by resident and infiltrating macrophages is cytotoxic to glomerular mesangial and epithelial cells, and impairs glomerular hemodynamics and filtration [27]. ICAM-1 and E-selectin expression in the glomerular endothelium is induced by pro-inflammatory cytokines and promotes leukocyte recruitment [21, 27].

Inflammation-mediated alterations impair the filtration function of the glomerulus, which relies on size and charge separation. Filtration rate depends on the pressure across the filter and its coefficient of filtration, which is determined by its structural composition and surface area (Fig. 4). The filter’s size and charge selectivity are lost and its permeability increases as glomerular endothelial cells lining the capillaries lose their characteristic fenestrations and as their overlying glycocalyx layer is degraded [53]. Thickening of the glomerular basement membrane due to extracellular matrix deposition correlates with progression of albuminuria and declining GFR, and is one of the earliest histological signs of DKD [8, 52]. The membrane may double in thickness in people with diabetes, from a normal thickness of around 300–350 nm [8]. Podocyte stress, injury and eventual loss are also key factors in disease progression. Podocytes create slit diaphragms for filtration with their foot processes, secrete basement membrane components, communicate with fenestrated endothelial cells, and endocytose proteins that pass through the barrier [54]. Injured podocytes retract their foot processes, disrupting the structure of the filter, and this ‘effacement’ leads to development of proteinuria [55].

Determinants of glomerular filtration rate. Classic nephrology equation describing how GFR depends on the pressure across the filter and its coefficient of filtration, which is determined by its structural composition and surface area. In DKD, structural composition is impaired by loss of endothelial fenestration, injury and loss of podocytes and thickening of the glomerular basement membrane, and surface area is reduced by mesangial expansion due to fibrosis. ESRD End stage renal disease

Resorption and secretion

Excess protein, advanced glycation end-products, growth factors and complement proteins in glomerular filtrate harm proximal tubular epithelial cells and activate pro-inflammatory responses [45]. Inflammatory and pro-fibrotic cytokines trigger de-differentiation of tubular epithelial cells, leading to loss of resorptive and secretory activities and acquisition of mesenchymal cell-like features, including production of extracellular matrix [56]. Disruption of normal uptake of proteins from the glomerular filtrate by proximal tubular epithelial cells contributes to development of proteinuria [57]. The relative contribution of tubular pathology might increase if SGLT2 inhibitor use slows progression of glomerular pathology, potentially increasing the importance of this compartment. Tubular epithelial cells produce pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic cytokines and chemokines including CCL2, IL-8, TGF-β and CCL5 (also known as RANTES) [29]. The resulting inflammation leads to tissue damage, with resulting hypoxia, apoptosis, tubular atrophy, disconnection of the tubule from the glomerulus, and eventual renal failure [58].

Extracellular matrix regulation

Mesangial expansion with eventual fibrosis is a histopathological hallmark of DKD. Excessive accumulation of extracellular matrix leads to fibrosis and impaired function throughout the chronically inflamed diabetic kidney [59]. Fibrosis prevents mesangial cells from expanding and contracting to control capillary blood pressure and the surface area of the glomerular filter, with resulting impairment in filtration [60]. Tubulointerstitial fibrosis expands the space between the tubular basement membrane and the peritubular capillaries, leading to reduced blood flow, hypoxia, and further epithelial damage and inflammation, and eventual tubular atrophy [59].

Pro-fibrotic mediators released by activated macrophages and injured epithelial cells upregulate extracellular matrix production in various cell types [22, 61]. These include mesangial cells, which normally secrete extracellular matrix to provide structural support for the glomerular capillary tuft [60], and perivascular fibroblasts, which normally provide structural support to the kidney microvasculature [62]. Potential biomarkers of renal fibrosis include TGF-β and matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP-2) [63]. TGF-β produced by pro-fibrotic macrophages upregulates expression of extracellular matrix proteins in kidney endothelial and epithelial cells [59, 61]. Oxidative and mechanical stress also directly enhance extracellular matrix production and contribute to fibrosis [61].

Perfusion

Ischaemia is a key trigger of inflammation in DKD, especially in the highly metabolically active tubular epithelium. Impaired perfusion leads to hypoxic injury, triggering inflammation, fibrosis, tubular atrophy and progression of DKD [64]. Type 2 diabetes is characterized by a more ischaemic kidney phenotype than the oxidative and proliferative pattern seen with type 1 diabetes [65, 66]. Oxygen demand in the tubules leads to sustained activation of the intrarenal renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, causing glomerular capillary hypertension that further damages glomerular endothelial and mesangial cells and podocytes [67]. Excessive oxygen levels in glomerular tissues lead to oxidative stress and formation of reactive oxygen species and advanced glycation end-products, with resulting inflammation and fibrosis [64]. Angiotensin II also directly activates pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic signaling pathways, contributing to endothelial cell injury and loss [68].

High glucose levels and advanced glycation end-products impair nitric oxide production by kidney endothelial cells, leading to impaired vasodilation in patients with DKD. Nitric oxide deficiency exacerbates oxidative stress, leading to further dysfunction and injury not only of epithelial cells but also adjacent cells, including podocytes [69]. Under oxidative stress, dimeric endothelial nitric oxide synthase decouples and produces superoxide instead of nitric oxide, which exacerbates both oxidative stress and nitric oxide deficiency [70]. Microvascular rarefaction in DKD eventually results from damage and apoptotic loss of endothelial cells together with impaired function of endothelial progenitor cells due to the impact of oxidative stress, advanced glycation end-products, and an inflammatory, pro-fibrotic milieu [69].

Pre-clinical research using the five-compartment model

The five-compartment model provides a framework for rationalizing the array of different animal models of type 2 diabetes, with the aim of linking pre-clinical research to clinical development based on pathophysiology in particular patient groups. In this section, we summarize the key features of commonly used pre-clinical models and how they translate to the five described compartments of inflammation. This may help with selection of the best pre-clinical model to use to define pathophysiological mechanisms in DKD. However, none of the available animal models faithfully replicates all aspects of DKD in humans, most notably because none involves progression to renal failure.

Rodent models

Most rodent models of DKD involve induction of diabetes-like phenotypes by streptozotocin treatment, spontaneous mutations, or genetic manipulation in laboratory mice (Mus musculus). Current mouse models have been successfully used with clinical standard of care in DKD and may address some inflammatory compartments, but study of ‘immune cell recruitment’ and ‘perfusion’ have remained challenging (Table 2) [71].

Streptozotocin is a cytotoxic glucose analogue that ablates pancreatic islet β cells, with severity of diabetes-like features depending on the mouse strain. In C57BL/6 J or Balb/c mice, streptozotocin induces only mild or moderate disease, but severity can be increased using genetic modification, crossing with other strains or a high-fat diet. Combing streptozotocin with hyperlipidaemia by knocking out Apoe (encoding apolipoprotein E) accelerates and worsens renal injury in C57BL/6 mice [8, 72]. Mutations in Akita and OVE26 mice cause pancreatic β cells toxicity, and the severity of the diabetes-like disease also varies depending on mouse strain. In db/db mice, a genetic defect in the leptin receptor leads to obesity, diabetes, and some signs of DKD. Surgical removal of one kidney (uninephrectomy) accelerates progression of kidney pathology in db/db mice [72]. Genetic knockout of Nos3 (encoding eNOS) or overactivation of the renin–angiotensin system in TTRhRen mice also accelerate loss of kidney function in mouse models (Table 2) [8, 72].

Non-rodent models

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) have been used to study ‘filtration’ and ‘immune cell recruitment’ in DKD. Zebrafish offer low cost, high throughput, and an advanced transgenic toolbox for molecular genetic manipulation, at the cost of potential low translatability to human disease. The kidney spontaneously regenerates in fish, providing challenges to test the effectiveness of potential therapeutics. Zebrafish have been used to study genetic variants that lead to podocyte damage and DKD [73, 74].

Models in domestic pigs (Sus scrofa) recapitulate features of DKD in all five compartments. A high-fat high-fructose diet induces renal hypertension, endothelial dysfunction and inflammation, and streptozotocin plus high-fat diet induces renal injury and proteinuria. Genetic manipulation to insert the Akita mutation into pigs leads to diabetes, but changes in kidney function have not yet been described [72].

Non-human primates (Macaca mulatta) are the gold standard for animal models of human kidney disease, but ethical considerations, high cost and the difficulty of genetic manipulation limit respective investigations. Streptozotocin administration leads to histopathological changes, proteinuria and impaired GFR, with the fastest disease progression observed using uncontrolled blood glucose levels and a high-fat, high-salt diet [72]. Still, aged dysmetabolic non-human primate models may offer the most suitable disease model, particularly as aging may be an important factor in DKD [75].

Organoids

Organoids are three-dimensional tissue structures derived by in vitro differentiation of induced pluripotent or other stem cells [76]. Blood vessel organoids with capillary networks, develop thickening of the basement membrane after exposure to high glucose levels and inflammatory cytokines, potentially providing a model for investigation of microvascular aspects of DKD [77]. The latest kidney organoids comprise connected nephrons and collecting ducts, and research is ongoing into nephropathy and fibrosis for DKD target validation [76].

Clinical trial design using the five-compartment model

The recent addition of SGLT2 inhibitors to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) as standard of care for DKD promise a reduction in risk for adverse renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes, most likely via a hemodynamic and metabolic mechanism of action [78,79,80,81]. Nevertheless, many patients with DKD remain at high risk of kidney disease progression and still bear the majority of the increased risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality among patients with type 2 diabetes [82, 83]. This indicates a persistent need for novel treatments that target different pathophysiological pathways such as inflammation [21,22,23].

Diagnostic inaccuracy in DKD is a major challenge in part due to a classification system categorizing kidney disease according to chronicity and severity based on non-specific markers; and in part due to the unique, often multimorbid heterogeneity of patients with DKD [84]. Several important international efforts, including the U.S. Kidney Precision Medicine Project and the European BEAt-DKD Consortium, have been initiated to better characterize the pathology of human DKD and the factors involved in its progression ([85] https://www.beat-dkd.eu/). Meticulous alignment of patient’s needs, scientific hypothesis, pre-clinical model systems and clinical studies will be paramount to efficiently translate relevant findings into novel treatment paradigms [86]. The five-compartment model presented here aims to contribute to this endeavor by providing a function-based framework to map the diverse pathological mechanisms in renal inflammation onto central, measurable kidney functions.

In both type 1 and type 2 diabetes, rate of renal function decline and kidney failure are associated with circulating inflammatory proteins, including tumor necrosis factor receptors 1 (TNF-R1) and TNF-R2 [5, 35, 87,88,89,90]. Within the kidney, innate and adaptive immune responses have been correlated with structural lesions, including TLR4- and CCL2-based pathways [91]. Markers of inflammation may therefore be useful for both prognosis as well as treatment response in DKD [92]. However, the relationship between systemic and local low-grade inflammation and the glomerular, vascular or tubulointerstitial damage in patients remains rather unclear [93]. For example, infliximab (anti-TNF monoclonal antibody) and etanercept (TNF-R2-Fc) decreased albuminuria in animal models of diabetes and 24 weeks of 4 mg baricitinib (a JAK1/2 inhibitor; n = 25) significantly reduced morning urinary albumin-to-creatine ratio (UACR; –41%), as well as plasma TNF-R1 and TNF-R2, in a small phase 2 study in DKD relative to placebo (n = 27) [34, 94,95,96].

Patient selection and endpoints in published and ongoing studies

No anti-inflammatory drugs for the treatment of DKD have progressed beyond phase 2 clinical trials, except maybe for finerenone (Table 3). Finerenone, a non-steroidal selective mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist that induces natriuresis with reduced hyperkalaemia compared with steroidal antagonists (e.g. spironolactone), may retain some potentially beneficial anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic effects [38]. In two large phase 3 studies in patients with DKD (FIDELIO- and FIGARO-DKD), finerenone was significantly more effective than standard of care including ACEi and ARBs in slowing the decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and improving cardiovascular outcomes, with non-significant reductions in end-stage kidney disease and all-cause mortality [38, 97].

A key challenge for the development of new anti-inflammatory medicines is the limited understanding of relevant surrogate endpoints for early clinical development before phase 3 [98] Most published trials have used the traditional markers of UACR and eGFR both as baseline patient selection criteria and as efficacy measures (Table 3). So far, the most reliable surrogate kidney endpoints seem to be a 30% improvement in albuminuria within 6 months, time to 30% decline in eGFR from baseline, and mean reduction in the slope of eGFR decline greater than 0.5–1.0 mL/min/1.73 m2/year over at least 2 years [99,100,101,102]. A sample size of approximately 100 patients per arm provides 80% power to detect a 30% reduction in UACR at 6 months, making it an appealing surrogate endpoint for a phase 2 efficacy study [103]. However, short-term UACR parameters have a legacy from studies of anti-hypertensive medications which may not be appropriate for studies of anti-inflammatory drugs. Rates of progression in UACR vary substantially from patient to patient due to differences in underlying pathophysiology, as well as race, comorbidities and sex [104, 105]. The resulting inflammation-independent diversity presents a challenge to adequate statistical powering of clinical studies, even assuming that the investigational drug can improve short-term UACR in ‘all comers’ with DKD. Also, albuminuria-based endpoints do not differentiate between glomerular and tubular loss of protein (the ‘filtration’ and ‘resorption’ compartments of our conceptual model). In the future, the over-all prevalence of albuminuria in patients may, furthermore, decline substantially with increasing take-up of standard care involving anti-hypertensive medications and SGLT2 inhibitors [106,107,108].

Lack of efficacy on renal functional outcomes like UACR or eGFR led to failure of several drug classes at phase 2, including those targeting pathways implicated in the pathophysiology of DKD (e.g. IL-1β antibodies and Janus kinase inhibitors). Unpredictable adverse drug reactions led to failure for bardoxolone (activator of the Nrf2 pathway and an inhibitor of the NF-κB pathway) and the vascular adhesion protein 1 inhibitor ASP8232, despite promising phase 2 kidney function outcomes (Table 3) [109, 110]. The generally disappointing results of trials of anti-inflammatory therapies to date hence indicate a need for improved, compartment-focused selection criteria and outcome measures.

Ziltivekimab, a fully human monoclonal antibody directed against the IL-6 ligand, was evaluated in a randomised, double-blind, phase 2 trial involving individuals (n = 264) with elevated high-sensitivity CRP and chronic kidney disease [111]. The primary study outcome was percentage change from baseline in high-sensitivity CRP after 12 weeks of treatment with ziltivekimab (7.5 mg, 15 mg and 30 mg) compared with placebo. Biomarker and safety data were collected over 24 weeks of treatment. After 12 weeks, median high-sensitivity CRP levels were reduced by 77% for the 7·5 mg group, 88% for the 15 mg group, and 92% for the 30 mg group compared with 4% for the placebo group. Dose-dependent reductions in fibrinogen, serum amyloid A, haptoglobin, secretory phospholipase A2, and lipoprotein(a) were observed. Ziltivekimab was well tolerated. Based on these data showing markedly reduced biomarkers of inflammation and thrombosis relevant to atherosclerosis a further trial is planned to investigate the effect of ziltivekimab in patients with chronic kidney disease, increased high-sensitivity CRP, and established cardiovascular disease.

Patient selection based on predominant immunopathology

Maximizing the potential benefits of new treatments involves identifying the compartments most affected by immunopathology in individual patients with DKD. The five-compartment model may serve as a guide for development of tools and therapies that will enable physicians to provide the right treatment to the right patients consistently and accurately, ideally without the need for kidney biopsy. Approaches that will allow patient classification include genomic and transcriptomic studies and identification of novel fluid-phase and imaging biomarkers. However, robust interventional trials are still needed to fully validate these exploratory endpoints.

Circulating biomarkers may allow patients to be identified based on molecular features of inflammation, and stratified based on predominant immunopathology [112]. For example, plasma levels of TNFR-1, TNFR-2 and kidney injury molecule 1 (KIM-1) are associated with decline in eGFR, even after adjustment for baseline albuminuria and eGFR, in multiple cohorts of patients with type 2 diabetes [5, 35, 87, 89, 90, 113]. A proteomics study recently identified a ‘kidney risk inflammatory signature’ comprising a cluster of 17 circulating inflammatory biomarkers that strongly associate with development of end-stage renal disease in multiple ethnicities [34]. Although the cluster included pro-inflammatory mediators already implicated in DKD (e.g. CCL2), it also included chemokines and ILs that were not known to be associated with the disease [34]. This suggests that relevant immunopathological pathways remain to be elucidated.

Inflammatory responses stimulated by toll-like receptors (TLRs), notably TLR4, appear to play a decisive role in the progression of DKD [114, 115] while complement dysregulation, may also contribute to progression [116]. Furthermore, the renal NF-κB pathway, implicated in the development and progression of experimental DKD, may also become an important therapeutic target [117].

Genomic and transcriptomic studies also offer routes to discovery of novel markers. Academic-industry systems biology consortiums aim to share molecular target identification efforts and expertise to accelerate novel drug development (e.g. the Renal Pre-Competitive Consortium [RPC2]) [118]. In a recent RNA-seq study, micro-dissected glomerular and tubulointerstitial kidney biopsy tissue fractions were analyzed from patients with DKD and matched living kidney donors. The results confirmed inflammatory responses, complement activation and extracellular matrix deposition as key pathophysiological processes [119]. A whole-exome sequencing study, in 3315 patients with chronic kidney disease and 9536 controls, used in vivo and in vitro approaches to validate the most strongly associated genes as potential novel diagnostic or therapeutic targets [120]. The analysis identified 93 genes with a strong CKD correlation which after ranking based on literature data supporting a link to CKD relevant biology resulted in 31 genes that were further evaluated in vitro and in vivo. Ultimately a single gene was identified as a CKD target that entered the pipeline for drug discovery.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can detect changes that precede albuminuria and GFR decline in patients with DKD [121]. Ischaemic regions of the kidney can be identified using blood oxygenation level-dependent MRI, and these signals are predictive of chronic kidney disease progression [122, 123]. Renal fibrosis identified using diffusion-weighted MRI may detect DKD progression earlier than eGFR [124]. Early impairment in renal perfusion in patients with diabetes can be identified using arterial spin labelling MRI, and these signals correlate with reduced GFR [125].

Combining these rapid advances in histology, genetics, ‘omics’, and imaging may unlock the potential of anti-inflammatory therapies in DKD. Eventually, patient stratification by specific and relevant pathophysiology, integrated with pre-clinical models of these disease processes, may allow intervention with novel targeted therapies in the right patients at the right time.

Nevertheless, limitations of the five-compartment model include that not all patients with histopathological indicators of DKD will ultimately develop the condition [126].

Conclusion

Compelling evidence indicates that sub-clinical chronic inflammation plays a key role in the development and progression of DKD. Successful development of novel anti-inflammatory therapies will involve targeting specific pathways in specific patients with DKD. Novel medicines will not be unique to each individual but will be tailored for optimal treatment of particular subgroups of the patient population. This precision medicine approach has the potential to maximize positive health outcomes while minimizing unnecessary side effects and costs, but it requires a significantly improved understanding of DKD. Our conceptual model provides a framework for identifying and assessing novel drugs that act in five key compartments of kidney function: immune cell recruitment and activation; filtration; resorption and secretion; extracellular matrix regulation; and perfusion. The model is intended to inform selection of pre-clinical models to identify and validate candidates for clinical testing, as well as design of clinical trials with selection criteria and efficacy measures that can provide early evidence of clinical benefit in patients with DKD. The aim of the model is to prevent cardiovascular mortality and progression to end-stage renal disease, which will remain high in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease despite recent improvements to standard of care.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Cho NH, Shaw JE, Karuranga S, Huang Y, da Rocha Fernandes JD, Ohlrogge AW, Malanda B. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;138:271–81.

Thomas B. The global burden of diabetic kidney disease: time trends and gender gaps. Curr Diab Rep. 2019;19(4):18.

Alicic RZ, Rooney MT, Tuttle KR. Diabetic kidney disease: challenges, progress, and possibilities. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(12):2032–45.

Oishi Y, Manabe I. Organ system crosstalk in cardiometabolic disease in the age of multimorbidity. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020;7:64.

Saulnier PJ, Gand E, Ragot S, Ducrocq G, Halimi JM, Hulin-Delmotte C, Llaty P, Montaigne D, Rigalleau V, Roussel R, et al. Association of serum concentration of TNFR1 with all-cause mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease: follow-up of the SURDIAGENE Cohort. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(5):1425–31.

Descamps-Latscha B, Witko-Sarsat V, Nguyen-Khoa T, Nguyen AT, Gausson V, Mothu N, London GM, Jungers P. Advanced oxidation protein products as risk factors for atherosclerotic cardiovascular events in nondiabetic predialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45(1):39–47.

Sarnak MJ, Jaber BL. Mortality caused by sepsis in patients with end-stage renal disease compared with the general population. Kidney Int. 2000;58(4):1758–64.

Najafian B, Alpers CE: Pathology of the kidney in diabetes. In: Diabetic nephropathy: pathophysiology and clinical aspects. edn. Edited by Roelofs JJ, Vogt L: Springer, Cham.; 2019.

Kimmelstiel P, Wilson C: Intercapillary lesions in the glomeruli of the kidney. Am J Pathol 1936, 12(1):83–98 87.

Bülow RD, Boor P. Extracellular matrix in kidney fibrosis: more than just a scaffold. J Histochem Cytochem. 2019;67(9):643–61.

Furuta T, Saito T, Ootaka T, Soma J, Obara K, Abe K, Yoshinaga K. The role of macrophages in diabetic glomerulosclerosis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1993;21(5):480–5.

Nguyen D, Ping F, Mu W, Hill P, Atkins RC, Chadban SJ. Macrophage accumulation in human progressive diabetic nephropathy. Nephrology (Carlton). 2006;11(3):226–31.

Klessens CQF, Zandbergen M, Wolterbeek R, Bruijn JA, Rabelink TJ, Bajema IM. DHT IJ: Macrophages in diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32(8):1322–9.

Yonemoto S, Machiguchi T, Nomura K, Minakata T, Nanno M, Yoshida H. Correlations of tissue macrophages and cytoskeletal protein expression with renal fibrosis in patients with diabetes mellitus. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2006;10(3):186–92.

Awad AS, Kinsey GR, Khutsishvili K, Gao T, Bolton WK, Okusa MD. Monocyte/macrophage chemokine receptor CCR2 mediates diabetic renal injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;301(6):F1358-1366.

de Zeeuw D: The future of diabetic kidney disease management: reducing the unmet need. J Nephrol 2020.

Redondo MJ, Hagopian WA, Oram R, Steck AK, Vehik K, Weedon M, Balasubramanyam A, Dabelea D. The clinical consequences of heterogeneity within and between different diabetes types. Diabetologia. 2020;63(10):2040–8.

Gonzalez Suarez ML, Thomas DB, Barisoni L, Fornoni A. Diabetic nephropathy: Is it time yet for routine kidney biopsy? World J Diabetes. 2013;4(6):245–55.

Fiorentino M, Bolignano D, Tesar V, Pisano A, Biesen WV, Tripepi G, D’Arrigo G, Gesualdo L. Group E-EIW: Renal biopsy in patients with diabetes: a pooled meta-analysis of 48 studies. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32(1):97–110.

Tervaert TWC, Mooyaart AL, Amann K, Cohen AH, Cook HT, Drachenberg CB, Ferrario F, Fogo AB, Haas M, de Heer E, et al. Pathologic Classification of Diabetic Nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21(4):556–63.

Donate-Correa J, Luis-Rodriguez D, Martin-Nunez E, Tagua VG, Hernandez-Carballo C, Ferri C, Rodriguez-Rodriguez AE, Mora-Fernandez C, Navarro-Gonzalez JF: Inflammatory targets in diabetic nephropathy. J Clin Med 2020, 9(2).

Rayego-Mateos S, Morgado-Pascual JL, Opazo-Rios L, Guerrero-Hue M, Garcia-Caballero C, Vazquez-Carballo C, Mas S, Sanz AB, Herencia C, Mezzano S et al: Pathogenic Pathways and Therapeutic Approaches Targeting Inflammation in Diabetic Nephropathy. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21(11).

Tang SCW, Yiu WH. Innate immunity in diabetic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16(4):206–22.

Furman D, Campisi J, Verdin E, Carrera-Bastos P, Targ S, Franceschi C, Ferrucci L, Gilroy DW, Fasano A, Miller GW, et al. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nat Med. 2019;25(12):1822–32.

Duni A, Liakopoulos V, Roumeliotis S, Peschos D, Dounousi E: Oxidative stress in the pathogenesis and evolution of chronic kidney disease: untangling Ariadne's thread. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20(15).

Chagnac A, Zingerman B, Rozen-Zvi B, Herman-Edelstein M. Consequences of glomerular hyperfiltration: the role of physical forces in the pathogenesis of chronic kidney disease in diabetes and obesity. Nephron. 2019;143(1):38–42.

Ijpelaar DHT: Inflammatory processes in diabetic glomeruli. In: Diabetic nephropathy: pathophysiology and clinical aspects. edn. Edited by Roelofs JJ, Vogt L: Springer, Cham.; 2019.

Brandt S, Ballhause TM, Bernhardt A, Becker A, Salaru D, Le-Deffge HM, Fehr A, Fu Y, Philipsen L, Djudjaj S et al: Fibrosis and immune cell infiltration are separate events regulated by cell-specific receptor notch3 expression. J Am Soc Nephrol 2020.

Vallon V, Thomson SC. The tubular hypothesis of nephron filtration and diabetic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16(6):317–36.

Scurt FG, Menne J, Brandt S, Bernhardt A, Mertens PR, Haller H, Chatzikyrkou C, Committee RS. Systemic inflammation precedes microalbuminuria in diabetes. Kidney Int Rep. 2019;4(10):1373–86.

Winter L, Wong LA, Jerums G, Seah JM, Clarke M, Tan SM, Coughlan MT, MacIsaac RJ, Ekinci EI. Use of readily accessible inflammatory markers to predict diabetic kidney disease. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018;9:225.

Moriwaki Y, Yamamoto T, Shibutani Y, Aoki E, Tsutsumi Z, Takahashi S, Okamura H, Koga M, Fukuchi M, Hada T. Elevated levels of interleukin-18 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in serum of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: relationship with diabetic nephropathy. Metabolism. 2003;52(5):605–8.

Satirapoj B, Dispan R, Radinahamed P, Kitiyakara C. Urinary epidermal growth factor, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 or their ratio as predictors for rapid loss of renal function in type 2 diabetic patients with diabetic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 2018;19(1):246.

Niewczas MA, Pavkov ME, Skupien J, Smiles A, Md Dom ZI, Wilson JM, Park J, Nair V, Schlafly A, Saulnier PJ, et al. A signature of circulating inflammatory proteins and development of end-stage renal disease in diabetes. Nat Med. 2019;25(5):805–13.

Coca SG, Nadkarni GN, Huang Y, Moledina DG, Rao V, Zhang J, Ferket B, Crowley ST, Fried LF, Parikh CR. Plasma biomarkers and kidney function decline in early and established diabetic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(9):2786–93.

Barrera-Chimal J, Jaisser F. Pathophysiologic mechanisms in diabetic kidney disease: A focus on current and future therapeutic targets. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22(Suppl 1):16–31.

Warren AM, Knudsen ST, Cooper ME. Diabetic nephropathy: an insight into molecular mechanisms and emerging therapies. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2019;23(7):579–91.

Bakris GL, Agarwal R, Anker SD, Pitt B, Ruilope LM, Rossing P, Kolkhof P, Nowack C, Schloemer P, Joseph A, et al. Effect of finerenone on chronic kidney disease outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(23):2219–29.

Baker M, Perazella MA. NSAIDs in CKD: Are They Safe? Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;76(4):546–57.

Iwai T, Miyazaki M, Yamada G, Nakayama M, Yamamoto T, Satoh M, Sato H, Ito S. Diabetes mellitus as a cause or comorbidity of chronic kidney disease and its outcomes: the Gonryo study. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2018;22(2):328–36.

Chang TI, Park JT, Kim JK, Kim SJ, Oh HJ, Yoo DE, Han SH, Yoo TH, Kang SW. Renal outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes with or without coexisting non-diabetic renal disease. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;92(2):198–204.

Kanter JE, Hsu CC, Bornfeldt KE. Monocytes and macrophages as protagonists in vascular complications of diabetes. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020;7:10.

Byun K, Yoo Y, Son M, Lee J, Jeong GB, Park YM, Salekdeh GH, Lee B. Advanced glycation end-products produced systemically and by macrophages: A common contributor to inflammation and degenerative diseases. Pharmacol Ther. 2017;177:44–55.

Garcia-Fernandez N, Jacobs-Cacha C, Mora-Gutierrez JM, Vergara A, Orbe J, Soler MJ: Matrix metalloproteinases in diabetic kidney disease. J Clin Med 2020, 9(2).

Perico N, Benigni A, Remuzzi G: Proteinuria and tubulotoxicity. In: Diabetic nephropathy: pathophysiology and clinical aspects. edn. Edited by Roelofs JJ, Vogt L: Springer, Cham.; 2019.

Finsterbusch M, Hall P, Li A, Devi S, Westhorpe CL, Kitching AR, Hickey MJ. Patrolling monocytes promote intravascular neutrophil activation and glomerular injury in the acutely inflamed glomerulus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(35):E5172-5181.

Turner-Stokes T, Garcia Diaz A, Pinheiro D, Prendecki M, McAdoo SP, Roufosse C, Cook HT, Pusey CD, Woollard KJ. Live Imaging of Monocyte Subsets in Immune Complex-Mediated Glomerulonephritis Reveals Distinct Phenotypes and Effector Functions. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(11):2523–42.

Stamatiades EG, Tremblay ME, Bohm M, Crozet L, Bisht K, Kao D, Coelho C, Fan X, Yewdell WT, Davidson A, et al. Immune Monitoring of Trans-endothelial Transport by Kidney-Resident Macrophages. Cell. 2016;166(4):991–1003.

Tang PM, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Lan HY. Macrophages: versatile players in renal inflammation and fibrosis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2019;15(3):144–58.

Tonneijck L, Muskiet MH, Smits MM, van Bommel EJ, Heerspink HJ, van Raalte DH, Joles JA. Glomerular hyperfiltration in diabetes: mechanisms, clinical significance, and treatment. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(4):1023–39.

Molitch ME, Gao X, Bebu I, de Boer IH, Lachin J, Paterson A, Perkins B, Saenger AK, Steffes M, Zinman B, et al. Early glomerular hyperfiltration and long-term kidney outcomes in type 1 diabetes: the DCCT/EDIC experience. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14(6):854–61.

Marshall CB. Rethinking glomerular basement membrane thickening in diabetic nephropathy: adaptive or pathogenic? Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;311(5):F831–43.

van der Vlag J, Buijsers B: The glomerular endothelium in diabetic nephropathy: role of heparanase. In: Diabetic nephropathy: pathophysiology and clinical aspects. edn. Edited by Roelofs JJ, Vogt L: Springer, Cham.; 2019.

Reiser J, Altintas MM: Podocytes. F1000Res 2016, 5.

Kravets I, Mallipattu SK: The Role of Podocytes and Podocyte-Associated Biomarkers in Diagnosis and Treatment of Diabetic Kidney Disease. J Endocr Soc 2020, 4(4):bvaa029.

Kriz W, Kaissling B, Le Hir M. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in kidney fibrosis: fact or fantasy? J Clin Invest. 2011;121(2):468–74.

D’Amico G, Bazzi C. Pathophysiology of proteinuria. Kidney Int. 2003;63(3):809–25.

Gilbert RE. Proximal tubulopathy: prime mover and key therapeutic target in diabetic kidney disease. Diabetes. 2017;66(4):791–800.

Humphreys BD. Mechanisms of renal fibrosis. Annu Rev Physiol. 2018;80:309–26.

Di Vincenzo A, Bettini S, Russo L, Mazzocut S, Mauer M, Fioretto P: Renal structure in type 2 diabetes: facts and misconceptions. J Nephrol 2020.

Nguyen TQ, Goldschmeding R: The mesangial cell in diabetic nephropathy. In: Diabetic nephropathy: pathophysiology and clinical aspects. edn. Edited by Roelofs JJ, Vogt L: Springer, Cham.; 2019.

Kramann R, Dirocco DP, Maarouf OH, Humphreys BD: Matrix producing cells in chronic kidney disease: origin, regulation, and activation. Curr Pathobiol Rep 2013, 1(4).

Mansour SG, Puthumana J, Coca SG, Gentry M, Parikh CR. Biomarkers for the detection of renal fibrosis and prediction of renal outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(1):72.

Hesp AC, Schaub JA, Prasad PV, Vallon V, Laverman GD, Bjornstad P, van Raalte DH. The role of renal hypoxia in the pathogenesis of diabetic kidney disease: a promising target for newer renoprotective agents including SGLT2 inhibitors? Kidney Int. 2020;98(3):579–89.

Takiyama Y, Haneda M. Hypoxia in Diabetic Kidneys. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014: 837421.

Ruggenenti P, Remuzzi G. Nephropathy of type 1 and type 2 diabetes: diverse pathophysiology, same treatment? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000;15(12):1900–2.

Siragy HM, Carey RM. Role of the intrarenal renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in chronic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol. 2010;31(6):541–50.

Patel DM, Bose M, Cooper ME: Glucose and blood pressure-dependent pathways – the progression of diabetic kidney disease. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21(6).

Dou L, Jourde-Chiche N: Endothelial toxicity of high glucose and its by-products in diabetic kidney disease. Toxins (Basel) 2019, 11(10).

Cheng H, Harris RC. Renal endothelial dysfunction in diabetic nephropathy. Cardiovasc Hematol Disord Drug Targets. 2014;14(1):22–33.

Callera GE, Antunes TT, Correa JW, Moorman D, Gutsol A, He Y, Cat AN, Briones AM, Montezano AC, Burns KD et al: Differential renal effects of candesartan at high and ultra-high doses in diabetic mice-potential role of the ACE2/AT2R/Mas axis. Biosci Rep 2016, 36(5).

Nguyen I, van Koppen A, Joles JA: Animal models of diabetic kidney disease. In: Diabetic nephropathy: pathophysiology and clinical aspects. edn. Edited by Roelofs JJ, Vogt L: Springer, Cham.; 2019.

Morales EE, Wingert RA. Zebrafish as a model of kidney disease. Results Probl Cell Differ. 2017;60:55–75.

Outtandy P, Russell C, Kleta R, Bockenhauer D. Zebrafish as a model for kidney function and disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2019;34(5):751–62.

Wikstrom J, Liu Y, Whatling C, Gan LM, Konings P, Mao B, Zhang C, Ji Y, Xiao YF, Wang Y. Diastolic dysfunction and impaired cardiac output reserve in dysmetabolic nonhuman primate with proteinuria. J Diabetes Complications. 2021;35(4): 107881.

Tsakmaki A, Fonseca Pedro P, Bewick GA. Diabetes through a 3D lens: organoid models. Diabetologia. 2020;63(6):1093–102.

Wimmer RA, Leopoldi A, Aichinger M, Wick N, Hantusch B, Novatchkova M, Taubenschmid J, Hammerle M, Esk C, Bagley JA, et al. Human blood vessel organoids as a model of diabetic vasculopathy. Nature. 2019;565(7740):505–10.

Neuen BL, Young T, Heerspink HJL, Neal B, Perkovic V, Billot L, Mahaffey KW, Charytan DM, Wheeler DC, Arnott C, et al. SGLT2 inhibitors for the prevention of kidney failure in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(11):845–54.

Kang Y, Zhan F, He M, Liu Z, Song X. Anti-inflammatory effects of sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors on atherosclerosis. Vascul Pharmacol. 2020;133–134: 106779.

Cowie MR, Fisher M: SGLT2 inhibitors: mechanisms of cardiovascular benefit beyond glycaemic control. Nat Rev Cardiol 2020.

Buse JB, Wexler DJ, Tsapas A, Rossing P, Mingrone G, Mathieu C, D'Alessio DA, Davies MJ: 2019 Update to: Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes, 2018. A Consensus Report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2020, 43(2):487–493.

Afkarian M, Sachs MC, Kestenbaum B, Hirsch IB, Tuttle KR, Himmelfarb J, de Boer IH. Kidney disease and increased mortality risk in type 2 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(2):302–8.

Fox CS, Matsushita K, Woodward M, Bilo HJ, Chalmers J, Heerspink HJ, Lee BJ, Perkins RM, Rossing P, Sairenchi T, et al. Associations of kidney disease measures with mortality and end-stage renal disease in individuals with and without diabetes: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;380(9854):1662–73.

KDIGO 2020 Clinical Practice Guideline for Diabetes Management in Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int 2020, 98(4s):S1-s115.

de Boer IH, Alpers CE, Azeloglu EU, Balis UGJ, Barasch JM, Barisoni L, Blank KN, Bomback AS, Brown K, Dagher PC, et al. Rationale and design of the Kidney Precision Medicine Project. Kidney Int. 2021;99(3):498–510.

Morgan P, Brown DG, Lennard S, Anderton MJ, Barrett JC, Eriksson U, Fidock M, Hamrén B, Johnson A, March RE, et al. Impact of a five-dimensional framework on R&D productivity at AstraZeneca. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2018;17(3):167–81.

Pavkov ME, Nelson RG, Knowler WC, Cheng Y, Krolewski AS, Niewczas MA. Elevation of circulating TNF receptors 1 and 2 increases the risk of end-stage renal disease in American Indians with type 2 diabetes. Kidney Int. 2015;87(4):812–9.

Forsblom C, Moran J, Harjutsalo V, Loughman T, Wadén J, Tolonen N, Thorn L, Saraheimo M, Gordin D, Groop PH, et al. Added value of soluble tumor necrosis factor-α receptor 1 as a biomarker of ESRD risk in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(8):2334–42.

Barr ELM, Barzi F, Hughes JT, Jerums G, Hoy WE, O’Dea K, Jones GRD, Lawton PD, Brown ADH, Thomas M, et al. High Baseline Levels of Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor 1 Are Associated With Progression of Kidney Disease in Indigenous Australians With Diabetes: The eGFR Follow-up Study. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(4):739–47.

Yamanouchi M, Skupien J, Niewczas MA, Smiles AM, Doria A, Stanton RC, Galecki AT, Duffin KL, Pullen N, Breyer MD, et al. Improved clinical trial enrollment criterion to identify patients with diabetes at risk of end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2017;92(1):258–66.

Smith KD. Toll-like receptors in kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2009;18(3):189–96.

Matoba K, Takeda Y, Nagai Y, Kawanami D, Utsunomiya K, Nishimura R. Unraveling the Role of Inflammation in the Pathogenesis of Diabetic Kidney Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(14):3393.

Andrade-Oliveira V, Foresto-Neto O, Watanabe IKM, Zatz R, Câmara NOS: Inflammation in Renal Diseases: New and Old Players. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2019, 10(1192).

Tuttle KR, Brosius FC 3rd, Adler SG, Kretzler M, Mehta RL, Tumlin JA, Tanaka Y, Haneda M, Liu J, Silk ME, et al. JAK1/JAK2 inhibition by baricitinib in diabetic kidney disease: results from a Phase 2 randomized controlled clinical trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2018;33(11):1950–9.

Omote K, Gohda T, Murakoshi M, Sasaki Y, Kazuno S, Fujimura T, Ishizaka M, Sonoda Y, Tomino Y. Role of the TNF pathway in the progression of diabetic nephropathy in KK-A(y) mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2014;306(11):F1335-1347.

Moriwaki Y, Inokuchi T, Yamamoto A, Ka T, Tsutsumi Z, Takahashi S, Yamamoto T. Effect of TNF-alpha inhibition on urinary albumin excretion in experimental diabetic rats. Acta Diabetol. 2007;44(4):215–8.

Pitt B, Filippatos G, Agarwal R, Anker SD, Bakris GL, Rossing P, Joseph A, Kolkhof P, Nowack C, Schloemer P, et al. Cardiovascular Events with Finerenone in Kidney Disease and Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(24):2252–63.

Herrington WG, Staplin N, Haynes R. Kidney disease trials for the 21st century: innovations in design and conduct. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16(3):173–85.

Levey AS, Gansevoort RT, Coresh J, Inker LA, Heerspink HL, Grams ME, Greene T, Tighiouart H, Matsushita K, Ballew SH, et al. Change in albuminuria and GFR as end points for clinical trials in early stages of CKD: a scientific workshop sponsored by the National Kidney Foundation in collaboration with the US Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;75(1):84–104.

Holtkamp F, Gudmundsdottir H, Maciulaitis R, Benda N, Thomson A, Vetter T. Change in albuminuria and estimated GFR as end points for clinical trials in early stages of CKD: a perspective from European regulators. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;75(1):6–8.

Thompson A, Smith K, Lawrence J. Change in estimated GFR and albuminuria as end points in clinical trials: a viewpoint from the FDA. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;75(1):4–5.

Inker LA, Heerspink HJL, Tighiouart H, Levey AS, Coresh J, Gansevoort RT, Simon AL, Ying J, Beck GJ, Wanner C, et al. GFR Slope as a surrogate end point for kidney disease progression in clinical trials: a meta-analysis of treatment effects of randomized controlled trials. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;30(9):1735–45.

Heerspink HJL, Law G, Psachoulia K, Connolly K, Whatling C, Ericsson H, Knöchel J, Lindstedt E-L, MacPhee I: Design of FLAIR: a phase 2b study of the 5-lipoxygenase-activating protein inhibitor AZD5718 in patients with proteinuric chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Rep 2021, [manuscript submitted].

Persson F, Rossing P: Diagnosis of diabetic kidney disease: state of the art and future perspective. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 2018, 8(1):2–7.

Ameh OI, Okpechi IG, Agyemang C, Kengne AP: Global, regional and ethnic differences in diabetic neuropathy. In: Diabetic nephropathy: pathophysiology and clinical aspects. edn. Edited by Roelofs JJ, Vogt L: Springer, Cham.; 2019.

Parving HH, Brenner BM, McMurray JJ, de Zeeuw D, Haffner SM, Solomon SD, Chaturvedi N, Persson F, Desai AS, Nicolaides M, et al. Cardiorenal end points in a trial of aliskiren for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(23):2204–13.

Fried LF, Emanuele N, Zhang JH, Brophy M, Conner TA, Duckworth W, Leehey DJ, McCullough PA, O’Connor T, Palevsky PM, et al. Combined angiotensin inhibition for the treatment of diabetic nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(20):1892–903.

Imai E, Chan JC, Ito S, Yamasaki T, Kobayashi F, Haneda M, Makino H. investigators Os: Effects of olmesartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes with overt nephropathy: a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled study. Diabetologia. 2011;54(12):2978–86.

Nangaku M, Kanda H, Takama H, Ichikawa T, Hase H, Akizawa T. Randomized clinical trial on the effect of bardoxolone methyl on GFR in diabetic kdidney disease patients (TSUBAKI study). Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5(6):879–90.

de Zeeuw D, Renfurm RW, Bakris G, Rossing P, Perkovic V, Hou FF, Nangaku M, Sharma K, Heerspink HJL, Garcia-Hernandez A, et al. Efficacy of a novel inhibitor of vascular adhesion protein-1 in reducing albuminuria in patients with diabetic kidney disease (ALBUM): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6(12):925–33.

Ridker PM, Devalaraja M, Baeres FMM, Engelmann MDM, Hovingh GK, Ivkovic M, Lo L, Kling D, Pergola P, Raj D, et al. IL-6 inhibition with ziltivekimab in patients at high atherosclerotic risk (RESCUE): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2021;397(10289):2060–9.

Alicic RZ, Johnson EJ, Tuttle KR. Inflammatory mechanisms as new biomarkers and therapeutic targets for diabetic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2018;25(2):181–91.

Forsblom C, Moran J, Harjutsalo V, Loughman T, Waden J, Tolonen N, Thorn L, Saraheimo M, Gordin D, Groop PH, et al. Added value of soluble tumor necrosis factor-alpha receptor 1 as a biomarker of ESRD risk in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(8):2334–42.

Feng Y, Yang S, Ma Y, Bai XY, Chen X. Role of Toll-like receptors in diabetic renal lesions in a miniature pig model. Sci Adv. 2015;1(5): e1400183.

Jialal I, Major AM, Devaraj S. Global Toll-like receptor 4 knockout results in decreased renal inflammation, fibrosis and podocytopathy. J Diabetes Complications. 2014;28(6):755–61.

Yu SM, Bonventre JV. Acute kidney injury and maladaptive tubular repair leading to renal fibrosis. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2020;29(3):310–8.

Foresto-Neto O, Albino AH, Arias SCA, Faustino VD, Zambom FFF, Cenedeze MA, Elias RM, Malheiros DMAC, Camara NOS, Fujihara CK, et al. NF-κB System Is Chronically Activated and Promotes Glomerular Injury in Experimental Type 1 Diabetic Kidney Disease. Front Physiol. 2020;11:84–84.

Tomilo M, Ascani H, Mirel B, Magnone MC, Quinn CM, Karihaloo A, Duffin K, Patel UD, Kretzler M. Renal Pre-competitive Consortium (RPC2): discovering therapeutic targets together. Drug Discov Today. 2018;23(10):1695–9.

Levin A, Reznichenko A, Witasp A, Liu P, Greasley PJ, Sorrentino A, Blondal T, Zambrano S, Nordstrom J, Bruchfeld A, et al. Novel insights into the disease transcriptome of human diabetic glomeruli and tubulointerstitium. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35(12):2059–72.

Identifying new CKD drug targets from genetic analysis. abstract presented at ASN Kidney Week (SA-PO407) [https://www.asn-online.org/education/kidneyweek/2019/program-abstract.aspx?controlId=3230586]

Gooding KM, Lienczewski C, Papale M, Koivuviita N, Maziarz M, Dutius Andersson AM, Sharma K, Pontrelli P, Garcia Hernandez A, Bailey J, et al. Prognostic imaging biomarkers for diabetic kidney disease (iBEAt): study protocol. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21(1):242.

Sugiyama K, Inoue T, Kozawa E, Ishikawa M, Shimada A, Kobayashi N, Tanaka J, Okada H. Reduced oxygenation but not fibrosis defined by functional magnetic resonance imaging predicts the long-term progression of chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35(6):964–70.

Pruijm M, Milani B, Pivin E, Podhajska A, Vogt B, Stuber M, Burnier M. Reduced cortical oxygenation predicts a progressive decline of renal function in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2018;93(4):932–40.

Berchtold L, Crowe LA, Friedli I, Legouis D, Moll S, de Perrot T, Martin PY, Vallee JP, de Seigneux S. Diffusion magnetic resonance imaging detects an increase in interstitial fibrosis earlier than the decline of renal function. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35(7):1274–6.

Mora-Gutierrez JM, Garcia-Fernandez N, Slon Roblero MF, Paramo JA, Escalada FJ, Wang DJ, Benito A, Fernandez-Seara MA. Arterial spin labeling MRI is able to detect early hemodynamic changes in diabetic nephropathy. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2017;46(6):1810–7.

Klessens CQF, Woutman TD, Veraar KAM, Zandbergen M, Valk EJJ, Rotmans JI, Wolterbeek R, Bruijn JA, Bajema IM. An autopsy study suggests that diabetic nephropathy is underdiagnosed. Kidney Int. 2016;90(1):149–56.

de Zeeuw D, Akizawa T, Audhya P, Bakris GL, Chin M, Christ-Schmidt H, Goldsberry A, Houser M, Krauth M, Lambers Heerspink HJ, et al. Bardoxolone methyl in type 2 diabetes and stage 4 chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(26):2492–503.

Chin MP, Reisman SA, Bakris GL, O’Grady M, Linde PG, McCullough PA, Packham D, Vaziri ND, Ward KW, Warnock DG, et al. Mechanisms contributing to adverse cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and stage 4 chronic kidney disease treated with bardoxolone methyl. Am J Nephrol. 2014;39(6):499–508.

Chertow GM, Pergola PE, Chen F, Kirby BJ, Sundy JS, Patel UD. Effects of selonsertib in patients with diabetic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;30(10):1980–90.

Gale JD, Gilbert S, Blumenthal S, Elliott T, Pergola PE, Goteti K, Scheele W, Perros-Huguet C. Effect of PF-04634817, an oral CCR2/5 chemokine receptor antagonist, on albuminuria in adults with overt diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int Rep. 2018;3(6):1316–27.

Hara A, Shimizu M, Hamaguchi E, Kakuda H, Ikeda K, Okumura T, Kitagawa K, Koshino Y, Kobayashi M, Takasawa K, et al. Propagermanium administration for patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy: A randomized pilot trial. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab. 2020;3(3): e00159.

Dimerix plans for next study in diabetic kidney disease patients [press release] [https://investors.dimerix.com/DownloadFile.axd?file=/Report/ComNews/20210128/02334227.pdf]

de Zeeuw D, Bekker P, Henkel E, Hasslacher C, Gouni-Berthold I, Mehling H, Potarca A, Tesar V, Heerspink HJ, Schall TJ. The effect of CCR2 inhibitor CCX140-B on residual albuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy: a randomised trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3(9):687–96.

Ruggenenti PL: Effects of MCP-1 inhibition by bindarit therapy in type 2 diabetes subjects with micro- or macro- albuminuria J Am Soc Nephrol 2010, 21:(Suppl. 1), 44A.

Ridker PM, MacFadyen JG, Glynn RJ, Koenig W, Libby P, Everett BM, Lefkowitz M, Thuren T, Cornel JH. Inhibition of interleukin-1β by canakinumab and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(21):2405–14.

Menne J, Eulberg D, Beyer D, Baumann M, Saudek F, Valkusz Z, Wiecek A, Haller H, Emapticap Study G. C-C motif-ligand 2 inhibition with emapticap pegol (NOX-E36) in type 2 diabetic patients with albuminuria. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32(2):307–15.

Acknowledgements

Under the direction of the authors, Matt Cottingham, PhD, of Oxford PharmaGenesis provided medical writing support funded by AstraZeneca.

Funding

AstraZeneca.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KJW and AH conceived the article and researched literature. AH, JW, LMG, MS, PBLH and KJW contributed to discussion of contents, and to writing, reviewing and editing the article. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors are employees of AstraZeneca and own stock or stock options. AstraZeneca develops and markets treatments for kidney disease.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hofherr, A., Williams, J., Gan, LM. et al. Targeting inflammation for the treatment of Diabetic Kidney Disease: a five-compartment mechanistic model. BMC Nephrol 23, 208 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-022-02794-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-022-02794-8