Abstract

Background

A potential pitfall of policies intended to promote referral for kidney transplant is that greater numbers of patients may be evaluated for transplant without experiencing the intended benefit of receiving a kidney. Little is known about the potential implications of this experience for patients.

Methods

We performed a thematic analysis of clinician documentation in the electronic medical records of all adults at a single medical center with advanced kidney disease who were referred to the local transplant coordinator for evaluation between 2008 and 2018 but did not receive a kidney.

Results

148 of 209 patients referred to the local kidney transplant coordinator at our center (71%) had not received a kidney by the end of follow-up. Three dominant themes emerged from qualitative analysis of documentation in the medical records of these patients: 1) Forward momentum: patients found themselves engaged in an iterative process of testing and treatment that tended to move forward unless an absolute contraindication to transplant was identified or patients disengaged; 2) Potential for transplant shapes other medical decisions: engagement in the transplant evaluation process could impact many other aspects of patients’ care; and 3) Personal responsibility and psychological burden for patients and families: clinician documentation suggested that patients felt personally responsible for the course of their evaluation and that the process could take an emotional toll on them and their family members.

Conclusions

Engagement in the kidney transplant evaluation process can be a significant undertaking for patients and families and may impact many other aspects of their care. Policies to promote referral for kidney transplant should be coupled with efforts to strengthen shared decision-making to ensure that the decision to undergo transplant evaluation is framed as an explicit choice with benefits, risks, and alternatives and patients have an opportunity to shape their involvement in this process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Kidney transplant is the preferred treatment for many patients with advanced kidney disease [1, 2], but the limited availability of donor organs means that not all patients who might benefit can receive a kidney. In order to increase access to kidney transplant and promote more equitable organ allocation, a number of nationwide initiatives are currently underway to encourage transplant referrals [3]. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) requires that patients on dialysis be educated about transplant as a treatment option [4] and has incorporated dialysis facility transplant rates into some quality metrics [5,6,7]. Other national and regional initiatives focus on educating patients with advanced kidney disease about the option of kidney transplant and encouraging living kidney donation [8,9,10,11]. Increasing access to kidney transplant among patients with advanced kidney disease is also a central objective of the recent presidential Executive Order on Advancing American Kidney Health [12].

Given the relatively limited supply of donor kidneys, policies intended to promote more widespread and equitable access to kidney transplant may have the unintended effect of increasing the number of patients who undergo evaluation for kidney transplant but do not ultimately receive a kidney. The medical and psychosocial evaluation process required for kidney transplant can be extensive, and may entail multiple clinic visits with specialists, diagnostic tests (e.g., cancer screening, cardiac angiography), and behavior modification (e.g., stopping tobacco use, improving diet) [13]. In order to gain insight into potential unintended consequences of policies to increase transplant referral, we conducted a qualitative analysis of the electronic medical records of patients who were evaluated for kidney transplant but did not receive a kidney.

Methods

Study design and cohort selection

We conducted a thematic analysis of documentation in the electronic medical records of patients referred to the kidney transplant coordinator at the Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS) in Seattle, WA over a ten-year period who had not received a kidney by the end of follow-up. The transplant coordinator at our medical center receives referrals for veterans with advanced kidney disease from providers practicing both within and outside the Veterans Affairs Health Care System (VA). The coordinator’s role is to provide early education around transplant, organize and facilitate initial steps in the evaluation process, refer potentially eligible patients to a regional transplant center, and coordinate post-transplant care. The transplant program at the VA medical center in Portland, Oregon serves as the primary referral center for the VAPSHCS, but patients may also be referred to other VA and non-VA transplant centers.

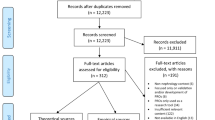

Between January 1, 2008 and January 1, 2018, 260 patients were included in a comprehensive clinical registry of referrals to the local transplant coordinator (Fig. 1). We excluded patients who had already received a transplant when they first interacted with the transplant coordinator (n = 19), those whose kidney function subsequently improved (n = 1), and those who were referred to the transplant coordinator but did not follow up with her either in person or by phone (n = 31). Among the remaining 209 patients referred for transplant evaluation, we further excluded those who received a kidney transplant during follow-up based on information in the local registry and/or electronic medical record (n = 61). Because our goal was to gain a broad perspective on the entire transplant evaluation process across multiple care settings for those who did not receive a kidney, patients were included regardless of how far they had progressed in the evaluation process (e.g., initial discussion, referral to a transplant center, waitlisting).

The analytic cohort for this study consisted of the 148 patients (71% of all patients who were referred to the VAPSHCS transplant coordinator for transplant evaluation) who were evaluated for kidney transplant but had not received a kidney as of January 2018. The VAPSHCS Institutional Review Board approved this study and waived the requirement to obtain patients’ informed consent.

Data collection

Each VA medical center maintains a comprehensive electronic medical record that includes all clinician notes for patients receiving care at that center. The electronic medical record system also includes a platform for remotely accessing patients’ records at other VA medical centers. One author (C.R.B. a senior nephrology fellow) reviewed the electronic medical records of all patients included in the registry to collect information on their age, sex, race, whether they were receiving dialysis at the time of first contact with the transplant coordinator, and whether they died during follow-up. Then, using a text search application embedded in the local electronic medical record to identify all mentions of the term “transplant” (which included all words with this root, e.g., transplants, transplanted, transplantation), she abstracted documentation pertaining to the transplant evaluation for each cohort member (both before and after referral to the transplant coordinator). She also manually reviewed all remote documentation for cohort members seen at regional VA transplant centers.

Analyses

Using inductive thematic analysis, an approach to analyzing text that facilitates discovery of previously unidentified concepts related to a phenomenon of interest [14], two investigators experienced in qualitative methodology (C.R.B. and A.M.O., a nephrologist at the Seattle VA) independently reviewed all abstracted passages from the electronic medical records of a random selection of 50 cohort members who had not received a transplant. We coded for concepts relevant to the transplant evaluation until we reached saturation, or the point at which no new concepts were identified with additional coding [15, 16]. C.R.B. then reviewed and coded all abstracted passages from the remaining 98 patients who were referred for transplant evaluation but did not receive a kidney during follow-up. Together, these two investigators iteratively reviewed codes to identify emergent themes, returning as needed to the primary passages to resolve differences in interpretation and ensure that emergent themes were grounded in the data [14, 16]. The two other coauthors (J.S.T. a medical anthropologist and P.P.R. a transplant nephrologist) then reviewed emergent themes and exemplar quotations. All four authors together developed the final thematic schema. The local transplant coordinator was consulted for member checking of the final schema and to address any privacy concerns she might have related to inclusion of illustrative quotations from her own chart notes. We used SPSS, version 19 (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL), for descriptive statistics and Atlas.ti version 8 (Scientific Software Development GmbH) to organize and store text and support initial coding and comparison across coders.

Results

Overall, 148 patients (71%) who were referred to and interacted with the local transplant coordinator from 2008 to 2018 had not received a kidney by the end of follow up. Their mean age at the time of first interaction with the transplant coordinator was 61.2 years (standard deviation (SD) 7.9 years) (Table 1). All 148 patients were male, 18.9% were Black, 56.8% were White, and cche end of follow-up.

Qualitative analysis

The following three overlapping and interrelated themes emerged through inductive thematic analysis of clinician documentation in patients’ electronic medical records: 1) Forward momentum; 2) Potential for transplant shapes other medical decisions; and 3) Personal responsibility and psychological burden for patients and families.

Theme 1. Forward momentum

Patients who were referred to the transplant coordinator found themselves engaged in an ongoing and iterative process of transplant evaluation that tended to move forward until an absolute contraindication was identified or the patient disengaged (Table 2).

The evaluation process proceeds reflexively.

Once initiated, the evaluation process tended to move forward unless there was a clear absolute medical, psychosocial, or behavioral contraindication to kidney transplant. Even when there was a recognized contraindication, clinicians might mention the possibility of resuming the evaluation process at a future time if the relevant barrier(s) could be addressed. Sometimes, patients were referred to a second transplant center after being declined by the primary center.

Patients’ ambivalence about proceeding with the transplant evaluation seemed less likely to halt the evaluation process than the presence of an absolute medical contraindication. It was rare for patients to make an overt decision to stop the evaluation in the absence of a clear contraindication. More commonly, we saw what appeared to be a passive process of disengagement whereby patients simply did not follow through with recommended clinic visits, testing, or treatments without any chart documentation to suggest that there had been an explicit decision not to pursue transplant.

A stepwise and piecemeal approach to testing and treatment

The transplant evaluation tended to be organized by organ system with a focus on identifying markers of disease severity that would constitute an absolute contraindication to kidney transplant. Components of the evaluation process were typically conducted in sequence, rather than in parallel, so that “major” contraindications would be identified early on. This stepwise approach to evaluation could be a source of frustration for some patients who, after successfully surmounting one barrier, might be surprised to learn that more testing lay ahead. Abnormal test results could also trigger a cascade of follow-up testing. While poor overall health, frailty, and functional limitations might be documented as concerning, these more global measures were rarely seen as absolute contraindications to transplant.

Uncertainty about what to expect from the evaluation process

Documentation in patients’ electronic medical records suggested that both they and their local providers were often uncertain about what the evaluation process might entail and about the requirements for transplant. Providers who were more peripherally involved in the evaluation process might rely on patients for information about the status of their candidacy. Subspecialists responsible for discrete components of the evaluation tended to assume a more technical role, deferring interpretation of test results to the transplant coordinator, nephrologist, or transplant team.

Theme 2. Potential for transplant shapes other medical decisions

The transplant evaluation unfolded in the broader context of patients’ other health conditions and evolving course of illness and could impact many other aspects of their care (Table 3).

Exposing and treating subclinical conditions

A variety of asymptomatic conditions might be identified during the transplant evaluation process (e.g., subclinical coronary artery disease, hepatic fibrosis, mild cognitive impairment). Detection of these abnormalities could prompt further testing and interventions not ordinarily indicated as part of routine care.

Decisions about transplant and dialysis are interdependent

Kidney transplant was sometimes framed as a way of avoiding dialysis or dialysis might be characterized as a bridge to transplant. Cardiac catheterization—which was a key component of the transplant evaluation for many patients—often raised concerns about precipitating the need for dialysis. For those on dialysis, the demands of their treatment schedule could make it difficult to participate in the transplant evaluation.

Transplant evaluation shapes other aspects of care

Patients and clinicians sometimes avoided treatment for symptomatic conditions (e.g., mood disorders, osteoarthritis) due to concerns about the potential implications this might have for transplant candidacy (e.g., by exposing psychological vulnerabilities or precipitating clinical deterioration). In other cases, tests and procedures required for the transplant evaluation might carry potential for harm or conflict with patients’ other goals and preferences. It was common to see medical treatments, diagnostic tests, and recommended behavioral modifications—many with potential health benefits in their own right—viewed by patients and providers through the narrow lens of how these might shape transplant candidacy.

Theme 3. Personal responsibility and psychological burden for patients and families

Electronic medical record documentation suggested that patients could feel personally responsible for the course of the transplant evaluation, and that the process could take an emotional toll on them and their families (Table 4).

Responsibility for becoming a “good candidate”

Chart documentation suggested that both patients and clinicians believed that personal motivation, willing engagement in the evaluation process, and adherence to treatment recommendations were essential if patients were to receive a kidney. Clinicians’ notes captured patients’ expressions of guilt and remorse about health factors and behaviors that might present barriers to transplant.

Documentation in patients’ medical records suggested that clinicians expected patients to assume primary responsibility for managing their medical conditions and addressing behavioral barriers to transplant candidacy. How patients conducted themselves during the transplant evaluation—and especially how they coped with dialysis treatment—tended to be viewed as a marker for how they would fare after transplant. Clinicians sometimes recommended changes to patients’ personal and social lives in order to strengthen their candidacy for transplant. Family members could also find themselves tasked with new responsibilities such as organizing a complex schedule of appointments and transportation.

Anxiety and psychological distress

The transplant evaluation process could have a deleterious psychological and emotional impact on patients and family members. The large number of required appointments and tests, scheduling, and transportation arrangements could be overwhelming. The transplant psychosocial evaluation could also be perceived as intrusive and/or embarrassing for some patients. Abrupt changes in expectations about candidacy, setbacks related to newly diagnosed health conditions, and news that transplant candidacy had been declined were documented as sources of disappointment, distress, and anxiety for patients and families. Clinicians’ notes also conveyed patients’ uncertainty about what to expect from the transplant evaluation process and poor understanding of selection criteria and rationale for selection decisions.

Discussion

Most patients evaluated for kidney transplant at our center from 2008 to 2018 did not receive a kidney. Our analyses suggest that engagement in the transplant evaluation process could take a substantial physical and emotional toll on these patients and their family members and impact many other aspects of their care. These findings suggest that policies to promote referral for transplant should be accompanied by efforts to strengthen shared decision-making to ensure that referral is framed as an explicit treatment choice with benefits, risks, and alternatives.

Despite the substantial tradeoffs involved, the transplant evaluation process tended to move forward in a somewhat reflexive fashion with few opportunities for patients to modulate their involvement short of simply not following through with clinicians’ recommendations. Testing undertaken as part of the evaluation could lead to a cascade of additional tests and treatments that would not ordinarily have been recommended as part of routine care, while an incremental and piecemeal approach to the evaluation process could also make it difficult for patients to anticipate what might lie ahead [17, 18]. This kind of forward clinical momentum—which has been described in a number of other clinical contexts—can limit opportunities for shared decision-making [19,20,21,22]. Not only can the promise of longevity and better quality of life through kidney transplant be difficult to resist [23,24,25] but the pursuit of transplant can become an all-consuming goal for many patients, with far-reaching impacts on other aspects of their care [26].

While it is appropriate that the transplant evaluation and selection process are shaped by societal considerations beyond the needs of individual patients, local clinicians and transplant center teams still have an obligation to support the values, goals, and preferences of patients and families to the greatest extent possible. Although many patients were highly motivated to receive a kidney, the evaluation process itself could be burdensome and emotionally taxing and could have unintended effects on many other aspects of care. Not only did patients experience disappointment at not receiving a kidney, but they might also feel morally responsible for the course of the evaluation [24, 27]. In light of these tradeoffs, our findings suggest that evaluation for transplant should be framed not simply as a preliminary step toward receiving a kidney, but as an explicit treatment choice in its own right [17, 28,29,30]. This may be especially important for older adults and/or those with multiple comorbidities, many of whom are both more susceptible than their younger counterparts to the unintended harms of the evaluation process and less likely to ultimately benefit by receiving a kidney [18, 31].

Our findings resonate with prior work describing how poor communication [32] and lack of clarity about what to expect from the transplant evaluation process among patients and their local clinicians [33,34,35] can serve as barriers to shared decision-making. Most prior work in this area has focused on later steps in the transplant process such as wait-listing, transplant surgery, and life after transplant [36,37,38,39,40]. Our findings add to this literature by suggesting that stronger efforts are needed to support shared decision-making early in the transplant evaluation process, including at the time of referral. This might include more explicit discussions about what the evaluation and selection process typically involves, consideration of patients’ hopes, expectations, and big-picture health priorities, and engagement of family members in the decision-making process [41, 42]. More work to elicit the perspectives of patients and families at different stages in the transplant evaluation process could also inform efforts to support a more person- and family-centered approach to referral decisions.

The availability of a comprehensive registry of patients referred for transplant evaluation at our center and the integrated nature of our medical system offered a rare window on the formative steps in the evaluation process and episodes of care occurring across a range of clinical settings that can otherwise be difficult to capture. This approach can be helpful in understanding complex care processes and treatment decisions that are well documented in the medical record. Nonetheless, our results should be interpreted with the following limitations in mind. First, the care processes described in this single-center study may not be directly relevant to patients cared for at other centers within or outside the VA. Second, our results may not describe care processes for groups of patients who are poorly represented in our study cohort (e.g., women and young adults). Because our goal was to identify themes relevant to patients who were evaluated for kidney transplant and did not receive a kidney and most (82.4%) of those included in the study died during follow-up, our findings are not intended to be generalizable to patients who complete the evaluation process and go on to receive a kidney. Third, because our goal was to identify themes relevant to the entire evaluation process, we did not distinguish between patients based on whether they were referred to a regional transplant center or added to the deceased donor waitlist. Finally, our analysis was based on clinician documentation in patients’ electronic medical records, and thus cannot fully describe the experiences and perspectives of patients, families, or clinicians.

Conclusion

The great majority of patients evaluated for transplant at our center from 2008 to 2018 did not receive a kidney. The themes that emerged from qualitative analysis of clinician documentation in the electronic medical records of these patients suggest that engagement in the transplant evaluation process can be a major undertaking for patients and families, can impact many other aspects of patients’ care, and offers few opportunities for patients to actively shape the process. These findings suggest that policies intended to increase referral for kidney transplant should be coupled with efforts to strengthen shared decision-making to ensure that this is framed as an explicit choice with potential benefits, risks, and alternatives.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study were obtained from patients' electronic medical records and are not publicly accessible.

Abbreviations

- CMS:

-

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- ESKD:

-

End-stage kidney disease

- UNOS:

-

United Network for Organ Sharing

- VAPSHCS:

-

Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System

- VA:

-

Veterans Affairs Health Care System

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

References

Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, Ojo AO, Ettenger RE, Agodoa LY, et al. Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(23):1725–30.

Legeai C, Andrianasolo RM, Moranne O, Snanoudj R, Hourmant M, Bauwens M, et al. Benefits of kidney transplantation for a national cohort of patients aged 70 years and older starting renal replacement therapy. Am J Transplant. 2018;18(11):2695-707.

Huml AM, Sedor JR, Poggio E, Patzer RE, Schold JD. An opt-out model for kidney transplant referral: the time has come. [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 9]. Am J Transplant. 2020.

Centers for Medicare & Medicade Services. Conditions for Coverage of End-Stage renal Disease Facilities; Final Rule. 42 C.F.R. §494.90(d) (2008).

Blankschaen SM, Saha S, Wish JB. Management of the Hemodialysis Unit: Core curriculum 2016. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;68(2):316–27.

Fowler KJ. Accountability of Dialysis Facilities in Transplant Referral: CMS Needs to Collect National Data on Dialysis Facility Kidney Transplant Referrals. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13. United States:193–4.

Paul S, Plantinga LC, Pastan SO, Gander JC, Mohan S, Patzer RE. Standardized transplantation referral ratio to assess performance of transplant referral among Dialysis facilities. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13(2):282–9.

Patzer RE, Perryman JP, Pastan S, Amaral S, Gazmararian JA, Klein M, et al. Impact of a patient education program on disparities in kidney transplant evaluation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(4):648–55.

Waterman AD, McSorley AM, Peipert JD, Goalby CJ, Peace LJ, Lutz PA, et al. Explore transplant at home: a randomized control trial of an educational intervention to increase transplant knowledge for black and white socioeconomically disadvantaged dialysis patients. BMC Nephrol. 2015;16:150.

Rodrigue JR, Paek MJ, Egbuna O, Waterman AD, Schold JD, Pavlakis M, et al. Making house calls increases living donor inquiries and evaluations for blacks on the kidney transplant waiting list. Transplantation. 2014;98(9):979–86.

Strigo TS, Ephraim PL, Pounds I, Hill-Briggs F, Darrell L, Ellis M, et al. The TALKS study to improve communication, logistical, and financial barriers to live donor kidney transplantation in African Americans: protocol of a randomized clinical trial. BMC Nephrol. 2015;16:160.

United States, Executive Order of the President [Donald Trump]. Executive order 13879: Advancing American Kidney Health. 2019.

Chadban SJ, Ahn C, Axelrod DA, Foster BJ, Kasiske BL, Kher V, et al. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline on the Evaluation and Management of Candidates for Kidney Transplantation. Transplantation. 2020;104(4S1 Suppl 1):S11–s103.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Birks M, Mills J. Grounded theory: a practical guide. 2nd ed. London: Sage Publications Inc; 2015.

Giacomini MK, Cook DJ. Users' guides to the medical literature: XXIII. Qualitative research in health care a. are the results of the study valid? Evidence-based medicine working group. JAMA. 2000;284(3):357–62.

Tinetti ME, Fried T. The end of the disease era. Am J Med. 2004;116(3):179–85.

Boyd C, Smith CD, Masoudi FA, Blaum CS, Dodson JA, Green AR, et al. Decision making for older adults with multiple chronic conditions: executive summary for the American Geriatrics Society guiding principles on the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):665-73.

Kruser JM, Cox CE, Schwarze ML. Clinical momentum in the intensive care unit. A latent contributor to unwanted care. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(3):426–31.

Wong SPY, McFarland LV, Liu CF, Laundry RJ, Hebert PL, O'Hare AM. Care Practices for Patients With Advanced Kidney Disease Who Forgo Maintenance Dialysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(3):305-13.

O'Hare AM, Murphy E, Butler CR, Richards CA. Achieving a person-centered approach to dialysis discontinuation: an historical perspective. Semin Dial. 2019;32(5):396-401.

Kaufman S. And a Time to Die: How American Hospitals Shape the End of Life. New York, NY: Scribner; 2005.

Shim JK, Russ AJ, Kaufman SR. Risk, life extension and the pursuit of medical possibility. Sociol Health Illn. 2006;28(4):479–502.

Kaufman SR, Shim JK, Russ AJ. Old age, life extension, and the character of medical choice. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2006;61(4):S175–84.

Russ AJ, Shim JK, Kaufman SR. The value of “life at any cost”: talk about stopping kidney dialysis. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(11):2236–47.

Kaufman S. Fairness and the tyranny of potential in kidney transplantation. Curr Anthropol. 2013;54(S7):S56–66.

Buchbinder M. Personhood diagnostics: personal attributes and clinical explanations of pain. Med Anthropol Q. 2011;25(4):457–78.

Bowling CB, O'Hare AM. Managing older adults with CKD: individualized versus disease-based approaches. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59(2):293–302.

Gordon EJ, Butt Z, Jensen SE, Lok-Ming Lehr A, Franklin J, Becker Y, et al. Opportunities for shared decision making in kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(5):1149–58.

Sawinski D, Foley DP. Personalizing the kidney transplant decision: who Doesn't benefit from a kidney transplant? Clin J am Soc Nephrol. 2019;15(2):279-81.

Guiding principles for the care of older adults with multimorbidity: an approach for clinicians. American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(10):E1–e25.

Lockwood MB, Saunders MR, Nass R, McGivern CL, Cunningham PN, Chon WJ, et al. Patient-reported barriers to the Prekidney transplant evaluation in an at-risk population in the United States. Prog Transplant. 2017;27(2):131–8.

Calestani M, Tonkin-Crine S, Pruthi R, Leydon G, Ravanan R, Bradley JA, et al. Patient attitudes towards kidney transplant listing: qualitative findings from the ATTOM study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29(11):2144–50.

Burns T, Fernandez R, Stephens M. The experiences of adults who are on dialysis and waiting for a renal transplant from a deceased donor: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2015;13(2):169–211.

Spiers J, Smith JA. Waiting for a kidney from a deceased donor: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Psychol Health Med. 2016;21(7):836–44.

Patzer RE, Basu M, Larsen CP, Pastan SO, Mohan S, Patzer M, et al. iChoose kidney: a clinical decision aid for kidney transplantation versus Dialysis treatment. Transplantation. 2016;100(3):630–9.

Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients. Kidney Transplant Provider Patient Partnerships: Empowering partnerships for informed decisions in kidney transplant [online tool]. Accessed Mar 2020. Retrieved from https://www.srtr.org/assets/media/Kidney_Transplant_Website/Home.html..

Axelrod DA, Kynard-Amerson CS, Wojciechowski D, Jacobs M, Lentine KL, Schnitzler M, et al. Cultural competency of a mobile, customized patient education tool for improving potential kidney transplant recipients’ knowledge and decision-making. Clin Transplant. 2017;31(5). https://doi.org/10.1111/ctr.12944.

Peipert JD, Hays RD, Kawakita S, Beaumont JL, Waterman AD. Measurement characteristics of the knowledge assessment of renal transplantation. Transplantation. 2019;103(3):565–72.

van Hoogdalem LE, Hoitsma A, Timman R, van der Zwart R, Kornmann J, van Rijssel T, et al. Shared decision-making in kidney patients: involvement in decisions regarding the quality of deceased donor kidneys. Transplant Proc. 2018;50(10):3152–9.

Boyd C, Smith CD, Masoudi FA, Blaum CS, Dodson JA, Green AR, et al. Framework for decision-making for older adults with multiple chronic conditions: executive summary of action steps for the AGS guiding principles on the Care of Older Adults with multimorbidity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):665-73.

Tong A, Hanson CS, Chapman JR, Halleck F, Budde K, Josephson MA, et al. 'Suspended in a paradox'-patient attitudes to wait-listing for kidney transplantation: systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Transpl Int. 2015;28(7):771–87.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Sandra Abrahamson, the Seattle VA transplant coordinator, for her assistance accessing the registry of patients evaluated for kidney transplant at our center and for her thoughtful insights.

Funding

Dr. Butler is supported by a training grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (5T32DK007467–33). Dr. Reese was supported by a grant from the Greenwall Foundation and an NIH, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease K-24 mentoring grant (K24AI146137-02). The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; in preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or in decision to submit for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.R.B. and A.M.O. designed the study; C.R.B collected data; C.R.B and A.M.O analyzed data, C.R.B. made the tables and figures; C.R.B. prepared the initial manuscript draft. C.R.B, A.M.O, J.S.T, and P.P.R contributed to the interpretation and presentation of data, revised the manuscript, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System Institutional Review Board approved this study and waived the requirement to obtain patients’ informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Butler, C.R., Taylor, J.S., Reese, P.P. et al. Thematic analysis of the medical records of patients evaluated for kidney transplant who did not receive a kidney. BMC Nephrol 21, 300 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-020-01951-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-020-01951-1