Abstract

Background

Palliative care has improved the quality of end-of-life (EOL) care and lowered the health care cost of cancer, and these benefits should be extended to patients with other serious illnesses including end-stage kidney disease. We evaluated the quality of EOL care, survival probabilities, and health care costs for dialysis patients in their last month of life.

Methods

We conducted a population-based study and analyzed data from Taiwan’s Longitudinal Health Insurance Database, which contains claims information of patient medical records, health care costs, and insurance system exit dates (our proxy for death between 2006 and 2011).

Results

Data of 1177 adult patients who died of chronic hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis were investigated. The mean age of these patients was 69.7 ± 11.9 years, and 585 (49.7%) were women. Some patients with dialysis received cardiopulmonary resuscitation (66.9%), died in a hospital (65.0%), or were admitted to an intensive care unit (51.0%) in the last month of life. We further classified these patients into two groups, namely dialysis with cancer (DC) (n = 149) and dialysis without cancer (D) (n = 1028). Only 19 dialysis patients received palliative care, and the proportion of patients receiving palliative care was higher in the DC group than in the D group (11.4% vs. 0.2%). The mean health care costs per person during the final month of life was similar between the DC and D groups (USD 2755 ± 259 vs. USD 2827 ± 88). Multivariate logistic regression showed that the DC group had lower odds of receiving cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) (OR: 0.39, CI = 0.26–0.56, p < 0.001) procedures, higher odds of longer hospital stays than the third quartile (> 25 days) (OR: 1.52, CI = 1.01–2.29, p = 0.0046), and higher odds of being hospitalized more than once (OR: 2.26, CI = 1.42–3.59, p = 0.001) than the D group in the last month of life after adjustments.

Conclusions

DC patients received hospice care more frequently, received CPR less frequently, and had similar health care costs. DC patients also had a higher risk of a hospital stay that lasted more than 25 days and more than one hospitalization compared with D patients in the final month of life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Worldwide, the population of dialysis patients has been increasing continuously for the past three decades [1, 2]. Factors that might contribute to the increase are the rapidly aging global population and diseases, such as diabetes and hypertension, which increase the risk of chronic kidney diseases, resulting in an increase in the need for dialysis [1, 3]. Taiwan reported the highest number of treated end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients at 3392 per million population (PMP) in 2016, followed by Japan at 2599 PMP and the United States 2196 PMP [2]. With advancements in dialysis and medical treatments, dialysis patient survival has increased in the past two decades [3]. The mortality of dialysis patients decreased by 26% from 2001 (187 per 1000 patient-years) to 2015 (138 per 1000 patient-years) in the United States [1]; however, the mortality did not significantly change between 2000 (113 per 1000 patient-years) and 2012 (120 per 1000 patient-years) in Taiwan [4]. Because Taiwan has the highest prevalence and incidence of dialysis worldwide, dialysis-related care has become a crucial public health and social issue.

Many dialysis patients have multiple comorbidities [5,6,7], and the patients reported feeling relatively dependent and less capable of participating in activities that they enjoyed. Therefore, these patients experienced an overall decline in functional status and quality of life [8]. A previous study reported that the prevalence of both physical and psychological symptoms was higher in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease than in those with advanced cancer in the last month of life [9]. The most common symptoms included fatigue, itchiness, drowsiness, dyspnea, poor concentration, pain, anorexia, edema, xerostomia, constipation, and nausea. The burden and severity of these symptoms increased in the last month of life [9].

End-of-life (EOL) care for dialysis patients is a crucial consideration for patients and their families, particularly when death is imminent. In the United States, the indicators of quality for patients with ESRD during the last 90 days of life are as follows: (1) number of hospital admissions, (2) days spent in the hospital, (3) intensive care unit (ICU) admissions, (4) intensive procedures received, such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), (5) inpatient surgical procedures received, and (6) inpatient deaths [10]. In the current study, we modified the conditions and measures for dialysis patients in Taiwan. The selected period was the last month of life; the indicators of inpatient surgical procedures were omitted, while the other indicators of quality were retained. Because dialysis is a significant risk factor for mortality during surgery, including hip fracture and coronary artery bypass grafting, surgery was not considered appropriate for patients in the last month of life [11, 12]. Investigations of EOL care are usually accepted in the last month of life [13, 14]. Hence, in the current study, we explored the quality indicators of EOL care of dialysis patients in the last month of life.

Palliative care is an interdisciplinary, team-based approach to symptom management, provision of psychological support, and treatment decision-making for patients with serious illnesses and their families. Increasing evidence highlights that patients with cancer at the EOL receive numerous benefits from palliative care, including reduction in symptom burden [15], improvement in quality of life and mood [16, 17], better overall survival [17, 18], and improvement in caregiver outcomes [19]; furthermore, these benefits were also observed in patients receiving cancer treatments [20]. In Taiwan, the use of palliative care has gradually progressed since 1983, and the first palliative ward was established in 1990 [21]. In Taiwan, the palliative care system includes both inpatient palliative care, which is the predominant type, and home palliative care; both types of care are covered by Taiwan’s National Health Insurance (NHI) program. Since 2009, the scope of palliative care has been extended beyond cancer to eight serious illnesses, including ESRD. However, the majority of palliative care continues to focus on treating patients with advanced cancer. Dialysis patients have a higher risk of cancer than do the nondialysis patients [22]. The causes of the high risks of cancers in chronic dialysis patients have not been elucidated adequately. Plants containing aristolochic acid were believed to cause renal damage and urinary tract cancer and a possible reason for the increased incidence of urinary tract cancer. To qualify for palliative care, patients must discontinue life-extending treatments provided at their hospice diagnosis, which includes dialysis for those with a hospice diagnosis of ESRD. In Taiwan, most patients with ESRD choose dialysis until death because of the low financial barriers to health insurance access, convenient medical access, and improvements in dialysis care [23]. Thus, these patients are not eligible for palliative care unless they have another diagnosis such as cancer, which meets the criteria for palliative care. However, the use of palliative care significantly increased among patients with cancer in Taiwan since 2000 because of the NHI’s reimbursement of palliative services. Two national policies promoting palliative services for terminal cancer patients were implemented in 2011 [24].

A previous study showed that family-reported quality of EOL care was higher for cancer patients than for patients with ESRD. [25] Therefore, we compared the quality of EOL care between chronic dialysis patients with and without cancer. Furthermore, we explored health care costs in the last month of life for the two groups of dialysis patients. Taiwan has a unique full-coverage dialysis policy. In Taiwan, dialysis health care costs increased from USD 68.4 million in 2000 to USD 1.54 billion in 2011, which is an increase of 125.15% [4]. Medical expenses of dialysis were higher among outpatients than among inpatients. Accordingly, expenses of dialysis patients burden Taiwan’s NHI program tremendously.

The use of administrative databases to investigate patients with chronic kidney disease is becoming increasingly common [26,27,28]. The use of these databases has several advantages; they can be used for examining the outcomes of large, population-based patient samples, and researchers can use less time-consuming and less expensive research protocols that offer a “real world” picture to test the effectiveness of interventions and compare care and outcomes among health providers, thus facilitating quality improvement initiatives [29]. A previous study reported that more than 80% of the terminal cancer patients with renal failure received hemodialysis (HD), and almost 20% of terminally ill cancer patients in palliative care received HD. [30] In the current study, quality indicators of EOL care were compared between chronic dialysis patients with and without cancer and to examine survival and health care costs in the last month of life.

Methods

Data source

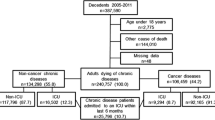

In this nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study, we analyzed data obtained from the Taiwanese National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD). The NHI program, implemented in March 1995, is a single-payer health insurance system, which covered approximately 99.9% of the total population in 2012 [31]. The NHIRD, a nationwide representative database containing all original claims data of one million NHI beneficiaries from 1996 to 2012, is a randomized, systemic sample of the 23.32 million NHI enrollees. According to the NHIRD, patients with dialysis are designated as those having a catastrophic illness and are issued a catastrophic illness certificate. Patients with ESRD (ICD-9-CM code 585) who had received HD or peritoneal dialysis (PD) continuously for 3 months, with four dialysis procedures per month, were searched from the NHIRD. We used the ICD-9-CM code and charge master code to identify cases of HD and PD (Additional file 1). Our study cohort included patients who had received chronic dialysis from 2006 to 2011, with follow-up until December 2012 by using the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2000 (LHID2000), a subset of the NHIRD that contains all the original claims data of one million individuals randomly sampled from the NHIRD in 2000 (Fig. 1). We excluded the patients with a follow-up period of < 30 days and those who were younger than 20 years of age.

Identification

Variables

Patient characteristics included age, sex, age at death, geographical location [32], urbanization level, and the final admission at a teaching hospital. Comorbid conditions listed in the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) [33] and common comorbidities (e.g., cancer, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, myocardial infarction [MI], congestive heart failure [CHF], peripheral arterial occlusive disease [PAOD], chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], pneumonia, sepsis, and potassium imbalance) were identified using ICD-9-CM codes. A previous study reported that the most common cause of death in dialysis patients aged ≥75 years was withdrawal from dialysis, followed by cardiovascular diseases and infections [34]. Therefore, we added the comorbid conditions MI, CHF, PAOD, COPD, pneumonia, sepsis, and potassium imbalance (hyperkalemia or hypokalemia) to our analysis. To increase the validity of diagnosis of diabetes or hypertension, we only included the patients with three reported diagnoses of diabetes [35] or hypertension [36] in their medical claims data based on the ICD-9-CM codes for these disease entities.

Variable definitions

Chronic dialysis

Chronic dialysis was defined as receiving dialysis continuously for 3 months with more than four dialysis procedures per month from the claims data of the NHI [37].

Grouping of the dialysis patients

The patients whose medical records showed that they were on chronic dialysis and had cancer were categorized into the dialysis and cancer (DC) group, while the patients who were on chronic dialysis and did not have cancer were categorized into the dialysis (D) group. The NHIRD and catastrophic illness databases were used to identify patients with cancer between 2006 and 2011.

Billing encounter codes for palliative care

The codes for palliative inpatient care included P1101K, P1102A, P1103B, P1104K, P1105A, P1106B, 05601 K, 05602A, 05603B, 03001 KB, 03002AB, 03003BB, and 03004BB. The codes for palliative home care included 05312C, 05313C, 05314C, 05315C, 05323C, 05324C, 05325C, 05326C, 05327C, and 06314C. The codes for palliative outpatient care included 05311C, 05312C, 05313C, 05314C, 05315C, 05316C, 05326C, and 05327C.

CCI

We calculated the CCI scores by examining ICD-9-CM-based diagnoses and procedure codes recorded using the Deyo method. We subsequently applied the calculated indices to inpatient and outpatient claims reported by Klabundle et al. [38, 39].

Health care costs

We calculated each patient’s health care costs by adding the outpatient and inpatient service costs listed in his or her claims records. We converted these costs to USD based on the exchange rate between the US Dollar and the New Taiwan Dollar in 2006 (USD 1.00 = NTD 32.53).

Socioeconomic status of an individual

Socioeconomic status (SES) is a crucial factor for health care use [40, 41]. We classified the SES into three groups, namely low, moderate, and high in accordance with a previous study [42]. Those earning less than USD 922 per month, between USD 922 and USD 3074, and more than USD 3074 per month were categorized into the low, moderate, and high SES groups, respectively.

Aggressive EOL care in the last month of life

These five quality indicators of EOL dialysis care in the final month of life are as follows: more than one hospitalization, long hospital stays [longer than Q3 (25 days)], ICU admissions, CPR administration, and death in a hospital.

Hospital deaths

If the date of discharge for the last admission was the same as the date of death [43], the patient was considered to have died in the hospital.

Statistical analysis

The distributional properties of continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation or standard error and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages. The survival duration was defined as the duration from the date of diagnosis of dialysis to the date of death (in years). Survival probabilities were analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method. Normality was examined using the Shapiro–Wilk test. In the univariate analysis, the two-sample t test, Wilcoxon rank-sum test, chi-squared test, and Fisher’s exact test were conducted to examine differences in the distributions of continuous variables and categorical variables between the DC and D groups.

We compared the patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics (Table 1), the primary causes of hospital admission in the last month of life (Table 2), and quality indicators in EOL dialysis care (Table 3) between the DC and D groups. All factors listed in Tables 1, 2, and 3 were included in the multivariate logistic regression models. A multivariate analysis was conducted using a stepwise variable selection procedure to determine the vital predictors of quality indicators during the last month of life. (Table 4) Collinearity between all the collected variables was checked.

Results

We enrolled 1177 adult patients on chronic dialysis (592 men and 585 women; ratio = 1.01:1) who died during 2006–2011. The patients usually exited from the insurance system after death, and the insurance system exit date was our proxy for death. The mean age of the patients was 69.7 ± 11.9 years. Among the chronic dialysis patients, 149 (12.7%) patients with cancer and 1028 (87.3%) were classified into the DC and D groups, respectively. Kidney and bladder (51, 34.2%), liver (35, 23.5%), and colon (24, 16.1%) cancer were the most common cancers in the DC group. Figure 1 presents the study design. Table 1 presents a comparison of the demographic characteristics of chronic dialysis patients between the DC and D groups. The percentage of diabetic patients in the DC group was lower than that in the D group (40.3% vs. 61.9%, p < 0.001). The percentage of patients with hypertension (70.5% vs. 78.1%, p = 0.047) and stroke (17.4% vs. 30.4%, p = 0.001) was also lower in the DC group than in the D group. The survival probabilities of dialysis patients between DC and D groups were not significantly different (p = 0.300) (Fig. 2). Table 2 presents a comparison of comorbid conditions in the last month of life between the DC and D groups. The DC group had a lower percentage of patients with congestive heart failure (4.7% vs. 10.0%, p = 0.034) and a higher percentage of patients with COPD (8.7% vs. 3.8%, p = 0.016) than did the D group.

Table 3 shows quality indicators of EOL dialysis care and health care cost comparisons between the DC and D groups during the last month of life. The DC group had significantly lower percentages of patients admitted to the ICU and patients who received CPR (42.3% vs. 52.2% [p = 0.028] and 47.0% vs. 69.8% [p < 0.001], respectively) than the D group. Furthermore, the DC group had a higher percentage of patients who were hospitalized more than once and had longer hospital stays (24.8% vs. 13.7% [p = 0.001] and 15.4 ± 11.3 vs. 12.7 ± 11.4 [p = 0.005], respectively) than the D group. The DC group had a higher percentage of hospital stays that were more than Q3 (> 25 days) (31.5% vs. 22.8%, p = 0.023) and deaths in hospital (73.2% vs. 63.8%, p = 0.027) compared with the D group. A higher percentage of cancer patients received palliative care than did those who did not have cancer (11.4% vs. 0.2%, p < 0.001). The mean days from patients receiving palliative care to death were 34.47 ± 60.36 days (median = 15 days). The mean health care costs per person during the final month of life of the patients of the DC group were approximately 2.5% less than those of the D group, but the difference was not statistically significant (USD 2755 ± 259 vs. USD 2827 ± 88, p = 0.917). We further calculated the health care costs between dialysis patients with and without palliative care in the last month of life. The mean health care costs per person during the final month of life for dialysis patients receiving palliative care was slightly less than those who did not receive palliative care, but it did not reach statistical significance (USD 1967 ± 55 vs. USD 2832 ± 108, p = 0.786).

Significant factors for the five quality indicators of EOL care were explored through multivariate logistic regression (Table 4). The independent factors listed in Tables 1, 2, and 3 were included in these procedures. The DC group had higher odds of hospital stays exceeding the third quartile (> 25 days in this study) (OR = 1.52, 95% CI = 1.02–2.29, p = 0.046), higher odds of more than one (≥2) hospitalization (OR = 2.26, 95% CI = 1.42–3.59, p = 0.001), and lower odds of receiving CPR (OR = 0.39, 95% CI = 0.26–0.56, p < 0.001) than the D group after adjustment for demographic variables (e.g., history of hypertension, high SES, living in northern Taiwan, living in a suburban area, and receiving service in the teaching hospital in the last month of life) and the primary causes of hospital admission in the last month of life (e.g., myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, PAOD, pneumonia, and sepsis) (listed in Additional file 2) (Table 4). The DC and D groups did not differ significantly in the percentage of patients receiving ICU care and dying in the hospital. In the current study, we found 20 patients (1.7%) who had received PD, and only 1 case belonged to DC group. The subgroup analysis for patients with only HD was similar to above results.

Discussion

In this study, a high percentage of dialysis patients received CPR (66.9%), died in a hospital (65.0%), and were admitted to an ICU (51.0%) in the last month of life, but a low percentage of patients received palliative care (1.6%). Other novel findings were that patients in the DC group received fewer intensive treatments, such as CPR, but had higher odds of long hospital stays (more than the third quartile or > 25 days in this study) and of more than one hospitalization in the last month of life after adjustments than did those in the group. Aggressive treatments, such as CPR and admission into the ICU in the last month of life, were critical issues concerning EOL care. In 2014, the percentage of elderly patients with ESRD in the United States who received CPR and were admitted into the ICU within the last 90 days of life was 34 and 62%, respectively [10]. We found that the DC patients received fewer CPR procedures than did the D patients. One explanation could be that national policies that promote palliative care results in a significant increase in palliative care use and decrease in CPR treatments in advanced cancer patients [24]. In the current study, we found that a higher percentage of patients in the DC group than in the D group received palliative care. We suggest that policymakers should actively promote palliative care programs for chronic dialysis patients to improve EOL dialysis care.

Till date, no study specifically investigated EOL care in dialysis patients in Taiwan. A previous study reported that incorporating palliative care into the dialysis units affects near-EOL patterns, and dialysis patients receiving palliative care had fewer ICU admissions and CPR sessions than did those without palliative care [44]. In this study, we found that 15.1% of dialysis patients had more than one hospitalization, and the mean hospital stay was 13.1 ± 11.4 days in the last month of life. In the United States, the overall percentage of hospital admissions among elderly patients with ESRD within the last 90 days of life was 83.4%, and the median number of times the patients were hospitalized was two, with a median hospital stay of 17 days between 2000 and 2014 [10]. In this study, we found that the DC patients were more likely to be hospitalized, have more than one hospital admission, and have hospital stays that were longer than 25 days in the last month of life than the D patients (24.8% vs. 13.7%, 15.4 ± 11.3 vs. 12.7 ± 11.4 days, 31.5% vs. 22.8%, respectively). One reason for these differences was that DC patients were frequently hospitalized for acute problems and symptom treatments. Timeliness in providing patients and their families with appropriate symptom assessments and treatments might be a solution that warrants further research.

Place of death has become a key indicator of EOL care; most patients prefer death at home [45]. In 2014, in the United States, the percentage of elderly patients with ESRD who died in the hospital (and not at home) was 40% [10]. In this study, we found that a higher percentage of chronic dialysis patients (65.0%) died in a hospital than at home, and the DC patients were more likely to die in a hospital than the D patients. A possible explanation for this finding might be a different definition of “dying in a hospital” in this study. If the discharge date for the last hospital admission was the same as the date of death, the patient was considered to have died in the hospital.

In Taiwan, patients with terminal illnesses requiring palliative service must be transferred to a palliative ward in a hospital for consultation and evaluation. During their palliative care course, frequent hospital admissions, long hospital stays, as well as admission to a hospital for relieving pain and other symptoms and subsequent death in the hospital in the last month of life for are expected. Culture might be a factor influencing the decision to die at home or in hospital among terminally ill patients. For example, dying patients were commonly and formally discharged from hospital “against medical advice” with artificial respiratory support to allow patients to die at home in Taiwan [46]. Another possible reason might be that in traditional Chinese culture, death is a sensitive topic; any mention of death is considered sacrilegious and is avoided [47]. Therefore, dying patients were often admitted, which might explain the increase in hospitalizations in the last month of life.

In this study, only 1.6% dialysis patients received palliative care in their last month of life, which is lower than that in the United States, 13.5 to 27% from 2002 to 2014 [10, 48]. The proportion of the patients who received palliative care was higher in the DC group (11.4%) than in the D group (0.2%). An explanation could be the national policies promoting palliative care for patients with cancer and the significant increase in palliative care use [24]. Promoting palliative care for dialysis patients and developing close cooperation and communication between palliative care and dialysis departments to improve patient care are the next steps for policy providers in Taiwan. Another resolution can be to promote the Renal Physician Association 2010 practice guidelines that were updated to affirm patients’ rights to refuse dialysis [49].

Due to the implementation of the NHI system in 1995, the number of patients receiving maintenance dialysis has increased rapidly. A previous study reported that the huge economic burden associated with dialysis is detrimental to the quality of dialysis treatment. Achieving a balance between the economics and quality of care requires multidisciplinary cooperation [50]. In this study, we found that the mean health care cost per person of DC patients during the final month of life was approximately 2.5% lower but not significantly different from that of D patients. A previous study recommended that the clinical practice of palliative care and dialysis withdrawal might be helpful for countries with NHI systems [51]. These recommendations also helped to improve EOL dialysis care and health care costs. Although palliative care is covered by the NHI program in Taiwan, the barriers to palliative care and withdrawing dialysis for patients with advanced renal failure in Taiwan include patient-related factors (e.g., differences in goals and values, lack of efficient communication with physicians, and lack of advanced care planning); physician-related factors (e.g., uncertainty regarding medical ethics, unfamiliarity with the law and regulation, and fear of legal issues), and system-related factors (e.g., not addressing preferences for dialysis, transition of care, lack of community-based palliative care systems, family-centered decision-making model, and special cultural considerations). [51]

Limitations

The quality indicators of EOL dialysis care have been challenged; therefore, we adopted and modified measures from the United States Renal System Data [10]. A previous study reported that scores on Kidney Disease Quality of Life-Short Form, which includes the subscales of physical functioning, emotional health, and social functioning, are strongly associated with 2-year mortality, independent of age and is a crucial quality indicator for EOL care [52]. This study has some limitations. First, the risk factors related to each quality indicator (e.g., clinical symptoms and signs, laboratory data, stages of cancer, and “do not resuscitate” orders) were not available from the administrative database. Second, the preferences of the patients and their family members treatment at the end of life may have affected some outcomes. A previous study reported that patients wanted to discuss advance care planning with their family rather than physicians. [53] Another previous study showed that the current EOL care failed to meet the needs of patients with advanced CKD; [54] future research is warranted to investigate the effectiveness of advance care planning for dialysis patients in Taiwan. Third, patients who received dialysis for < 3 months and < 12 times were excluded from this study because we wanted to eliminate the possibility of including patients with acute renal failure or renal failure patients with terminal illnesses. Fourth, in September 2009, the bureau of the NHI amended the fee-charging standard from patients with cancer to patients without cancer but with terminal illness, including ESRD. Hence, dialysis patients who received palliative care were limited before September 2009. Fifth, the results were not extended to PD patients in the current study, and we were unable to measure whether a patient received a kidney transplant. Sixth, this is a study of decedents, which provides valuable insights into EOL care, but is limited due to the non-prospective identification of patients (i.e., health care providers do not know which patients is going to die). Seventh, the information of withdrawal from dialysis was not available in the claims data. Finally, the retrospective design of this study was also a potential limitation.

Conclusions

This study indicated that a high proportion of dialysis patients received life-sustaining treatments (e.g., CPR treatments and ICU admissions) and died in a hospital, which might indicate that the patients and their families had unmet needs. We recommend that future studies investigate how to mitigate the suffering and distress of dialysis patients during EOL. Long hospital stays and frequent hospitalizations warrant further investigation. We suggest that policymakers improve accountability in EOL dialysis care and actively promote palliative care programs.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets are not publicly available but are available from the first author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AUC:

-

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

- CCI:

-

Charlson comorbidity index

- CIC:

-

Catastrophic illness certificate

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CPR:

-

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- EOL:

-

End-of-life

- ESRD:

-

End-stage renal disease

- HSS:

-

High socioeconomic status

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- LSS:

-

Low socioeconomic status

- MSS:

-

Moderate socioeconomic status

- NHI:

-

National Health Insurance

- NHIRD:

-

National Health Insurance Research Database

- PAOD:

-

Peripheral arterial occlusive disease

References

Thomas B, Wulf S, Bikbov B, et al. Maintenance Dialysis throughout the world in years 1990 and 2010. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26(11):2621–33.

United States Renal Data System: Chapter 11: internal comparisons. Available from: https://www.usrds.org/2018/view/v2_11.aspx. Accessed 20 Oct 2018.

Castro MCM. Reflections on end-of-life dialysis. J Bras Nefrol. 2018;40(3):233–41.

Taiwan Society of Nephrology. Taiwan Renal Data System (TWRDS) 2014. 2014_ARKDT_table. Available from : http://www.tsn.org.tw/UI/H/H00201.aspx. Accessed 1 Jan 2019.

O’Connor NR, Dougherty M, Harris PS, Casarett DJ. Survival after dialysis discontinuation and hospice enrollment for ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(12):2117–22.

Lin YT, Wu PH, Kuo MC, et al. High cost and low survival rate in high comorbidity incident elderly hemodialysis patients. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e75318.

Ng YY, Hung YN, Wu SC, et al. Progression in comorbidity before hemodialysis initiation is a valuable predictor of survival in incident patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(4):1005–12.

Schmidt RJ, Moss AH. Dying on dialysis: the case for a dignified withdrawal. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(1):174–80.

Murtagh FE, Addington-Hall J, Edmonds P, et al. Symptoms in the month before death for stage 5 chronic kidney disease patients managed without dialysis. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2010;40(3):342–52.

United States Renal Data System: Chapter 12: End-of-Life Care for Patients With End-stage Renal Disease: 2000–2014. Available from: https://www.usrds.org/2017/view/v2_11.aspx?zoom_highlight=international+comparison+report. Accessed 20 Oct 2018.

Hung LW, Hwang YT, Huang GS, et al. The influence of renal dialysis and hip fracture sites on the 10-year mortality of elderly hip fracture patients: a nationwide population-based observational study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(39):e7618.

Li HY, Chang CH, Lee CC, et al. Risk analysis of dialysis-dependent patients who underwent coronary artery bypass grafting: effects of dialysis modes on outcomes. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(39):e8146.

Ersek M, Miller SC, Wagner TH, et al. Association between aggressive care and bereaved families’ evaluation of end-of-life care for veterans with non-small cell lung cancer who died in veterans affairs facilities. Cancer. 2017;123(16):3186–94.

Fowler R, Hammer M. End-of-life care in Canada. Clin Invest Med. 2013;36(3):E127–32.

Jacobsen J, Jackson V, Dahlin C, et al. Components of early outpatient palliative care consultation in patients with metastatic nonsmall cell lung cancer. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(4):459–64.

Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302(7):741–9.

Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–42.

Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z, et al. Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(13):1438–45.

Dionne-Odom JN, Azuero A, Lyons KD, et al. Benefits of early versus delayed palliative care to informal family caregivers of patients with advanced Cancer: outcomes from the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(13):1446–52.

LeBlanc TW, El-Jawahri A. When and why should patients with hematologic malignancies see a palliative care specialist? Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2015;2015(1):471–8.

Lai YL, Su WH. Palliative medicine and the hospice movement in Taiwan. Support Care Cancer. 1997;5(5):348–50.

Lin MY, Kuo MC, Hung CC, et al. Association of dialysis with the risks of cancers. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0122856.

Shih CJ, Chen YT, Ou SM, et al. The impact of dialysis therapy on older patients with advanced chronic kidney disease: a nationwide population-based study. BMC Med. 2014;12:169.

Shao YY, Hsiue EH, Hsu CH, et al. National Policies Fostering Hospice Care Increased Hospice Utilization and reduced the invasiveness of end-of-life Care for Cancer Patients. Oncologist. 2017;22(7):843–9.

Wachterman MW, Pilver C, Smith D, Ersek M, Lipsitz SR, Keating NL. Quality of end-of-life care provided to patients with different serious illnesses. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(8):1095–102.

Lindsay RM, Hux J, Holland D, et al. An investigation of satellite hemodialysis fallbacks in the province of Ontario. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(3):603–8.

Prakash S, Austin PC, Oliver MJ, et al. Regional effects of satellite haemodialysis units on renal replacement therapy in non-urban Ontario, Canada. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22(8):2297–303.

Jain AK, McLeod I, Huo C, et al. When laboratories report estimated glomerular filtration rates in addition to serum creatinines, nephrology consults increase. Kidney Int. 2009;76(3):318–23.

Quinn RR, Laupacis A, Hux JE, et al. Predicting the risk of 1-year mortality in incident dialysis patients: accounting for case-mix severity in studies using administrative data. Med Care. 2011;49(3):257–66.

Kang SC, Lin CC, Chen YC, Wang WS. The impact of hemodialysis on terminal Cancer patients in hospices: a Nationwide retrospective study in Taiwan. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(2):188–92.

National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) Taiwan. Available from: http://nhird.nhri.org.tw/date_01.html. Accessed 20 Oct 2018.

Kreng VB, Yang CT. The equality of resource allocation in health care under the National Health Insurance System in Taiwan. Health Policy. 2011;100(2–3):203–10.

Marcus MW, Chen Y, Duffy SW, Field JK. Impact of comorbidity on lung cancer mortality - a report from the Liverpool lung project. Oncol Lett. 2015;9(4):1902–6.

Munshi SK, Vijayakumar N, Taub NA, et al. Outcome of renal replacement therapy in the very elderly. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16(1):128–33.

Lin CC, Lai MS, Syu CY, et al. Accuracy of diabetes diagnosis in health insurance claims data in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2005;104(3):157–63.

Yu KH, Kuo CF, Luo SF, et al. Risk of end-stage renal disease associated with gout: a nationwide population study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:R83.

Wu SC, Haung LG, Lei HL, Ng YY. Definition and analysis of patients with chronic dialysis from the National Health Insurance database. Taiwan J Public Health. 2004;23(5):419–27 (in Chinese).

Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613–9.

Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, Warren JL. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(12):1258–67.

Kangovi S, Barg FK, Carter T, et al. Understanding why patients of low socioeconomic status prefer hospitals over ambulatory care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(7):1196–203.

Lemstra M, Mackenbach J, Neudorf C, Nannapaneni U. High health care utilization and costs associated with lower socio-economic status: results from a linked dataset. Can J Public Health. 2009;100(3):180–3.

Chang CM, Huang KY, Hsu TW, et al. Multivariate analyses to assess the effects of surgeon and hospital volume on cancer survival rates: a nationwide population-based study in Taiwan. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40590.

Barbera L, Paszat L, Qiu F. End-of-life care in lung cancer patients in Ontario: aggressiveness of care in the population and a description of hospital admissions. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2008;35(3):267–74.

Lai CF, Hsu SH, Huang SJ. Incorporating palliative care into the Dialysis unit affects patterns near the end of life. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(9):1307–9.

Gomes B, Calanzani N, Gysels M, et al. Heterogeneity and changes in preferences for dying at home: a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care. 2013;12:7.

Tang ST, Wu SC, Hung YN, et al. Trends in quality of end-of-life care for Taiwanese cancer patients who died in 2000-2006. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(2):343–8.

Cheng HW, Li CW, Chan KY, et al. Bringing palliative care into geriatrics in a Chinese culture society--results of a collaborative model between palliative medicine and geriatrics unit in Hong Kong. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(4):779–81.

Murray AM, Arko C, Chen SC, et al. Use of hospice in the United States dialysis population. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(6):1248–55.

Shared decision-making in the appropriate initiation of and withdrawal from dialysis. Rockville; The Renal Physicians Association, 2010. Available from: https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.renalmd.org/resource/resmgr/Store/Shared_Decision_Making_Toolk.pdf. Accessed 20 Oct 2018.

Chen CF, Chen FA, Lee TL, et al. Current status of dialysis and vascular access in Taiwan. J Vasc Access. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1177/1129729818807336.

Lai CF, Tsai HB, Hsu SH, et al. Withdrawal from long-term hemodialysis in patients with end-stage renal disease in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2013;112(10):589–99.

van Loon IN, Bots ML, Boereboom FTJ, et al. Quality of life as indicator of poor outcome in hemodialysis: relation with mortality in different age groups. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(1):217.

Hines SC, Glover JJ, Holley JL, Babrow AS, Badzek LA, Moss AH. Dialysis patients’ preferences for family-based advance care planning. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(10):825–8.

Davison SN. End-of-life care preferences and needs: perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(2):195–204.

Acknowledgements

This study was partly based on data from the NHIRD provided by the Bureau of NHI, Department of Health, and managed by the National Health Research Institutes. The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not represent those of the Bureau of NHI, Department of Health, or National Health Research Institutes.

Funding

JK Chiang received research grants from Dalin Tzu Chi Hospital, Buddhist Tzu Chi Medical Foundation (DTCRD 105(2)-E-22). No funding source was involved in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JKC and YHK designed, conducted, and drafted the manuscript. JKC analyzed the data. JKC, JSC, and YHK contributed to the manuscript, revised the drafts critically for important intellectual content, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol for this study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Dalin Tzu Chi Hospital, Buddhist Tzu Chi Medical Foundation, Taiwan (No. B10304018). Because the analyzed NHIRD files contained only deidentified secondary data, the review board waived the requirement for informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

ICD-9-CM code and charge master codes to identify HD and PD cases. (DOC 23 kb)

Additional file 2:

Table S1. Significant factors for the quality indicators by using multivariate logistic regression for dialysis patients in the last month of life during 2006–2011. (DOC 52 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Chiang, JK., Chen, JS. & Kao, YH. Comparison of medical outcomes and health care costs at the end of life between dialysis patients with and without cancer: a national population-based study. BMC Nephrol 20, 265 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-019-1440-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-019-1440-9