Abstract

Background

Continuous quality improvement (CQI) has been successfully applied in business and engineering for over 60 years. While using CQI techniques within nephrology has received increased attention, little is known about where, and with what measure of success, CQI can be attributed to improving outcomes within nephrology care. This is particularly important as payors’ focus on value-based healthcare and reimbursement is tied to achieving quality improvement thresholds. We conducted a systematic review of CQI applications in nephrology.

Methods

Studies were identified from PubMed, MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, CINAHL, Google Scholar, ProQuest Dissertation Abstracts and sources of grey literature (i.e., available in print/electronic format but not controlled by commercial publishers) between January 1, 2004 and October 13, 2014. We developed a systematic evaluation protocol and pre-defined criteria for review. All citations were reviewed by two reviewers with disagreements resolved by consensus.

Results

We initially identified 468 publications; 40 were excluded as duplicates or not available/not in English. An additional 352 did not meet criteria for full review due to: 1. Not meeting criteria for inclusion = 196 (e.g., reviews, news articles, editorials) 2. Not nephrology-specific = 153, 3. Only available as abstracts = 3. Of 76 publications meeting criteria for full review, the majority [45 (61%)] focused on ESRD care. 74% explicitly stated use of specific CQI tools in their methods. The highest number of publications in a given year occurred in 2011 with 12 (16%) articles. 89% of studies were found in biomedical and allied health journals and most studies were performed in North America (52%). Only one was randomized and controlled although not blinded.

Conclusions

Despite calls for healthcare reform and funding to inspire innovative research, we found few high quality studies either rigorously evaluating the use of CQI in nephrology or reporting best practices. More rigorous research is needed to assess the mechanisms and attributes by which CQI impacts outcomes before there is further promotion of its use for improvement and reimbursement purposes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The United States health care system is one of the most expensive in the world, yet it ranks lowest among developed countries on many aspects of quality and performance [1–3]. Projections indicate there will be an epidemic growth of many chronic diseases in the future, including chronic kidney disease (CKD) [4]. Thus, identifying and addressing barriers to the delivery of high-quality, low-cost care is of paramount importance.

Continuous quality improvement (CQI) provides a systematic way to identify and address barriers to better outcomes. There is no single definition of CQI, but generally it is a management technique and set of tools to optimize systems and continually improve processes [5, 6] (Table 1). CQI methods have been used in the business and engineering sectors since the 1940’s and adoption of these techniques preceded Japan’s rise as a leading manufacturer post World War II [7].

More recently, CQI has been encouraged for use in healthcare [8]. Healthcare systems often have specific staff (i.e., quality officers) devoted to leading quality improvement efforts [9]. CQI modules are integral in medical training [10] including core curriculums for residency and fellowship education. There are a number of peer reviewed journals dedicated to publishing papers about CQI in healthcare--either as a primary or secondary focus of the journal (http://www.ihi.org/education/IHIOpenSchool/resources/Pages/WhereToSubmitYourWritingQIFriendlyPeerReviewedJournals.aspx) [11]. In addition, a recent series of articles promoted use of quality improvement tools in nephrology practice [12–16].

Although there has been interest in applying CQI within healthcare, and numerous reports of CQI processes that have been applied in healthcare, there appears to be a paucity of published literature systematically evaluating CQI use and its impact within medical contexts [17]. Past evaluations have been performed to assess effectiveness of CQI in some chronic conditions, [18] but there is heterogeneity in what exactly has been evaluated and how evaluations have been carried out [19]. This leaves some question as to how to interpret current evidence on the effectiveness of specific CQI strategies.

Over two decades ago, CQI was introduced and promoted for end-stage nephrology care by CMS [20]. Subsequent improvements were reported both in care patterns and clinical indices within U.S. dialysis populations [21–24]. But there is not yet a description on the state of evidence-based quality improvement science in the most recent time periods since, and across the continuum of nephrologic care. What quality tools have been used and evaluated? Where and how have they been successfully applied? Without having the answers to these questions, we are left promoting and adopting methods without fully understanding exactly how CQI has been used, where successes have been seen and whether changes observed are due to CQI itself or other factors.

We conducted a systematic review of the published literature to address these areas. The objectives of this review were to assess the extent CQI has been utilized in nephrology, identify temporal and/or spatial trends of use, assess if outcomes have been associated with CQI and determine which areas of nephrologic care have been most amenable to improvement efforts.

Methods

With the aid of a professional informationist, we conducted a systematic review of the literature regarding quality improvement in nephrology.

To adhere to established best practices, we aligned our review process with the “Preferred Reporting of Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses” (PRISMA) recommendations [25].

Protocol and eligibility

We defined our review to include full-text articles or reports in English that utilized continuous quality improvement to identify or address clinical, cost, efficiency, safety, communication, or process issues within nephrology. The search time-period was January 1, 2004 through October 1, 2014.

We considered research to be relevant if the CQI activities had been applied to participants (e.g., patients, providers), environmental issues, systems or processes. Our definition of “CQI” included methods that use quality improvement tools to (a) understand a process or system of care, (b) generate theories for why problems exist, (c) dissect why process issues in care occur, (d) choose best solutions to problems, (e) identify or improve current flow, or (f) institute remedies to fix problems. To be included, articles had to contain a CQI activity applied within an area of nephrology, e.g.,; chronic kidney disease (CKD), acute kidney injury, end stage renal disease (ESRD) or renal transplantation. Case reports, clinical practice guidelines, “thought” pieces, editorials, “state-of-affairs-reports”, literature reviews, news reports and meta-analyses were excluded.

To assess the nature and quality of the CQI work cited, articles were evaluated for whether a predefined outcome was measured, whether there was a follow up measurement post CQI activity, and if so, whether improvement in an outcome was identified.

Information sources and search strategy

Studies were identified by searching electronic databases and sources of gray literature. The literature search was applied to PubMed MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Google Scholar, and ProQuest Dissertation Abstracts. Pre-defined search algorithms were used to query PubMed MEDLINE as one part of the literature review and other databases as outlined above. Search terms used in PubMed MEDLINE were: ((("Nephrology" [Mesh] OR nephrology[tiab] OR renal[tiab] OR "Kidney Diseases" [Mesh]))) AND ((("Total Quality Management" [MeSH Terms] OR "Quality Improvement" [MeSH Terms] OR "quality improvement"[tiab] OR "Six Sigma" [tiab] OR "continuous quality improvement"[tiab] OR "total quality management" [tiab] OR "root cause" [tiab] OR "value stream" [tiab]))) NOT (Comment [ptyp] OR Editorial [ptyp] OR Letter [ptyp]). Terms were adapted for specific needs of each additional search engine.

Review team

An expert panel was convened for the review. This panel included one member both with a doctorate in Instructional Technology and a Masters in Library and Information Sciences (NM), four practicing nephrologists who also had training in epidemiology and public health (MH, PR, JHS, JWN), and one member with a doctorate in psychology, who also oversees a patient safety and quality scholars program for our health system (FJS).

Because definitions of CQI vary, several pre-review meetings of this team were used to define the scope of the review, define the questions we sought to answer and to establish a consensus definition of CQI. From these pre-review meetings we developed an initial algorithm for the review (Fig. 1). Two rounds of piloting the review process occurred whereby all members of the review panel reviewed an initial set of 20 citations, and subsequently met to discuss their independent reviews; the purpose was to clarify questions that arose and refine the review approach where needed. This served to maximize transparency, and ensure consistency in the reviews.

Study Selection and data abstraction

Two nephrologist reviewers evaluated the eligibility of each citation independently using citation title and abstract. One reviewer reviewed all citations (JWN) and each citation was co-reviewed by an additional reviewer (MH, JHS, or PR). Full text articles were retrieved for any citation deemed potentially relevant. The reviewers then met to review their independent evaluations of inclusion with the final eligibility confirmed in this co-review. Disagreements on inclusion were resolved by consensus. Data abstraction occurred once a citation was deemed to have met the eligibility criteria and agreed upon by consensus for inclusion by the two independent reviewers.

The team developed a set of characteristics that would be used to define the nature of the CQI activity described in each eligible study. Pre-defined forms for data abstraction were used in assessing these studies. Fields assessed included whether a specific CQI tool was described and if so, which tool. We assessed which outcomes were measured, the type of outcome, and whether there was a comparison group or baseline measure that showed improvement. We assessed the study trial type including whether the study was randomized with a control group. Additional data included continent of origin, year published, primary journal discipline, and area of nephrology where CQI was applied.

Data analysis and reporting

Abstracted data was summarized as frequency (n) and percent (%). Citations were managed using reference manager RefWorks (Copyright2015, Proquest LLC) and Endnote X4 (Copyright 1988-2010, Thompson-Reuters).

Results

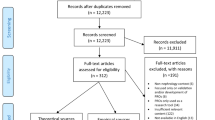

Figure 2 shows the flow of information through the different phases of our review. The search identified 468 citations from January 1, 2004 through October 1, 2014. After adjusting for duplicates, those not available in English, and those with no abstract available in print or online, we reviewed 428 citations. Of these, 153 were not on a topic directly related to nephrology and 196 did not meet criteria for inclusion (e.g., letters to editor, reviews, no clear mention of any CQI as a purpose at study outset, or no mention of CQI at all in methods). Seventy-nine met criteria for full review; three were only available in abstract form. Seventy-six were included in final quantitative analyses (Fig. 2).

Characteristics of the included 76 studies are as follows. Fifty-six (74%) explicitly provided mention of a specific CQI tool in their methods (e.g., value stream mapping, plan-do-check-act, root cause analysis or multi-disciplinary teams). Sixty-eight (89%) were published in biomedical and allied health journals. The number of studies peaked in 2011, with 12 reported in the literature (Fig. 3). Forty studies (52%) originated in North America, followed by 23 (30%) from Europe, and a total of 5 from Asia, 5 from Australia, 2 from South America, and 1 from Africa.

The majority of studies focused on CQI use within ESRD (61%), although there was overlap across sub-disciplines within nephrology in nine of these. One study spanned improvement efforts applicable to all of nephrology. Figure 4 shows a breakdown of studies within each nephrology sub-discipline (Fig. 4).

Table 2 summarizes by discipline the types of outcomes measured, where CQI techniques were applied and whether interdisciplinary teams were involved. Most outcomes were clinical (e.g., 34 of the 46 studies in ESRD or 74%). Explicit CQI techniques were most often used to identify problems or causes to problems, rather than focused on solutions to address them (Table 2).

In addition, four of the 76 studies were conducted within pediatric nephrology [26–29]. One used statistical process control to identify improvements in an intervention to increase CRRT filter life [26]. Another attempted to improve the pediatric dialysis experience using a ‘nursing intervention’- not well described [27]. Two other studies focused on populations in CKD not on dialysis-- developing protocols for managing nephrotic syndrome [29] and improving patient satisfaction [28].

Forty-two out of the 76 studies (55%) reported both a baseline or first-measured outcome and post measure outcome along with improvement. Of these, 23 focused on clinical outcomes, six were cost/efficiency related, and 11 included outcomes both clinical and cost/efficiency related. Following the trend of our overall sample, the majority of these studies (27 of the 42, 64%) occurred in end stage populations receiving hemodialysis—focusing on improving clinical indices (fistula rates/patency, anemia, high blood pressure). Some spanned systems of care; for example, one study used multi-disciplinary teams led by quality coaches to reduce contrast induced acute kidney injury across six hospitals [30].

Only one study of the 76 was randomized and controlled. It was not blinded due to the nature of the study [31]. Seventeen dialysis patients were randomized to a home blood pressure monitor plus an education intervention and 17 received usual care. Significant improvements in blood pressure were observed in the intervention group. The intervention was nursing driven and focused on home blood pressure monitoring to support patients in engaging in their own blood pressure management [31].

A table that lists all 76 articles and key areas of data we abstracted is located in the Additional file. (Additional file 1).

Discussion

Despite calls for healthcare reform [8] and funding for research promoting novel methods to improve care, [32] our review revealed little rigorous research examining impact or efficacy of CQI in nephrology. We identified only 76 published studies in a 10 year span. The majority of studies (66% including ESRD and interventional-related studies) focused at end stages of renal disease, missing an early opportunity to use CQI to optimize processes to prevent or abate disease progression. When applied, many CQI efforts used multi-disciplinary teamwork, not taking advantage of other well-developed methods like statistical process control or plan-do-check-act. Only slightly more than half of the studies included pre- and post-intervention outcome measures. These findings highlight a significant need for increased rigor in CQI research and reporting in nephrology.

CQI methods have reportedly been applied to multi-million (even billion) dollar industries outside of healthcare with considerable success. Boeing, a leading U.S. aerospace corporation, reported a 54 % reduction in build hours and 218 % increase in its build rate of helicopters during the 1990’s [33]. They reduced defects 90% while saving 1.5 million labor hours and halving delivery time of aircraft. CQI in healthcare has shown promise as well, [34] highlighted in experiences at the Virginia Mason Medical Center [35]. By adapting and implementing the Toyota Production System of quality improvement into its hospital and clinics, [36] teams redesigned care to better meet patients’ needs, reduced inefficiencies in nursing, and increased direct nursing care activities [35]. Given these successes, it is unclear why CQI has not been studies or reported on more widely and rigorously within the nephrologic literature.

Medical literature ideally involves a high level of scrutiny prior to publication-including a peer-reviewed vetting process and assurances that studies are designed to examine whether an intervention impacts outcomes. Perhaps CQI research designs or interventions are not familiar enough to traditional journals or do not measure up to rigors established for reporting [37]. It may also be that applications of CQI in nephrology are intended to meet internal needs of practices and not thought of as applicable to publish. One example may be found in the ESRD networks: all networks engage in regular regional improvement activities and routinely set out to achieve important clinical goals using CQI toolkits, [38] but are not typically designed for research publication. Although the study of CQI implementation may not be thought of as traditional research in the past, its use is promoted in medical literature, including a very recent and lengthy series of nephrology-specific articles [12–16].

Taken together, this indicates there may be a contradiction between what we do and promote through research to achieve best outcomes and what we do and promote in “real-life” to actually realize them. CQI efforts in nephrology should be published so that we can learn from others about how these tools work and which ones provide the most benefits. This review serves as a starting point to better understand these areas. But as with prior evaluations in other aspects of healthcare point out, [17, 19] a challenge remains for future studies using CQI; not only to report on how CQI has been implemented, but to acknowledge and address when changes do occur, that they occur because of CQI attributes and not because of other factors.

Another reason for paucity of reporting on CQI efforts in research or other literature may be that tools within CQI have not fully caught on with practitioners or researchers in the nephrology community. As stated above, this may change because there are a growing number of recent publications promoting its use [39, 40]. Moreover, CMS has promoted a focus on quality and performance measurements (i.e., quality metrics) to evaluate care and practice in ESRD for some time [20, 41]. This foundational work in the 1990’s and early 2000’s related to evaluation of quality initiatives in ESRD populations [21–24] may be the reason for our observation of a preponderance of studies in dialysis populations more recently.

But CQI can provide more than a basis to evaluate metrics in a focused area of one medical discipline. CQI offers tools to address problems and optimize processes across disparate areas of disease management. It can provide a foundation for culture and paradigm changes that support and sustain improvements, across the continuum of kidney care, even prior to renal replacement (Table 3).

There are potential limitations of this review. As in all reviews, there is risk for incomplete retrieval of all studies on topic-in this case CQI within nephrology. We attempted to minimize this risk by using broad and inclusive search criteria with multiple terms that encompassed both CQI and nephrology, spanning over ten years. We also applied our search outside of usual sources and into the gray literature, recognizing that non-traditional distribution channels may be more amenable to reporting on CQI efforts. Another limitation is that there is not one recognized and singular definition for CQI nor for what is deemed “CQI research”. We attempted to address this in several meetings of our expert panel to unify our approach and definitions, clarify potential relevant search terms and create a review protocol which we pilot-tested and then revised for clarity prior to the full review.

There are several important implications of this review. Only 19 of the 76 studies focused on pre-dialysis CKD with only four occurring in patients where kidney disease strikes early (pediatrics). With the majority of studies focused on end stages, clearly there remains a need to shift an equal if not larger focus from research in tertiary prevention to primary and secondary prevention [42]. There may also be a need to expand current efforts to educate those within nephrology research on CQI tools and how they can be applied across the spectrum of disease, a process in its infancy. With the majority of publications arising from North America, there may be opportunity to promote CQI education not only in U.S. nephrology training, but across the globe. Although there are some metrics established related to ESRD performance, we need more than metrics to effect the changes necessary to improve overall health in our populous. Lastly, as non-traditional research efforts expand, areas of research like implementation science (“(the) study of methods to promote…systematic uptake of research findings and other evidence-based practices into routine practice” [43] may lead to more reporting of CQI related studies [44].

Conclusions

To our knowledge this is the first systematic review of the published literature to determine how CQI has been applied to optimize outcomes in nephrology. We found that although there are CQI applications reported, the majority of studies mainly focused at end stages of disease, with comparison outcomes assessed just over half the time. There remains a significant and missed opportunity to examine CQI effectiveness and impact on outcomes, potentially as a way to usher in the sweeping improvement that is needed to address the gap between low quality and high cost seen in many chronic diseases including CKD.

Abbreviations

- CINAHL:

-

Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- CQI:

-

Continuous quality improvement

- ESRD:

-

End stage renal disease

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred reporting of items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

References

Davis K, Stremikis K, Schoen C, Squires D. Mirror, Mirror on the Wall, 2014 Update: How the U.S. Health Care System Compares Internationally. The Commonwealth Fund, June 2014. 2014

Poisal JA, Truffer C, Smith S, Sisko A, Cowan C, Keehan S, et al. Health spending projections through 2016: modest changes obscure part D's impact. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26:w242–253.

Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, Dietz W. Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: payer-and service-specific estimates. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28:w822–831.

Hoerger TJ, Simpson SA, Yarnoff BO, Pavkov ME, Rios Burrows N, Saydah SH, et al. The future burden of CKD in the United States: a simulation model for the CDC CKD Initiative. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65:403–11.

Riley WJ, Moran JW, Corso LC, Beitsch LM, Bialek R, Cofsky A. Defining quality improvement in public health. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2010;16:5–7.

Juran JM, Godfrey AB. Juran's Quality Handbook. 5th Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1999. p. 4.1-4.28, andAppendix V, p. AV.1.

Takahashi T. The paradox of Japan: what about CQI in health care? Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1997;23:60–4.

Crossing the Quality Chasm. A New Health System for the 21st Century. In: Institute of Medicine. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 2001.

Taitz JM, Lee TH, Sequist TD. A framework for engaging physicians in quality and saftety. BMJ Quality Saf. 2012;21(9):722-8.

Oyler J, Vinci L, Arora V, Johnson J. Teaching internal medicine residents quality improvement techniques using the abim’s practice improvement modules. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:927–30.

Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Open School. School Resources "Where to Submit Your Writing: Journals Publishing Student Work". http://www.ihi.org/education/IHIOpenSchool/resources/Pages/WhereToSubmitYourWritingQIFriendlyPeerReviewedJournals.aspx. Accessed 10 Nov 2016.

Chan CT, Chertow GM, Nesrallah G, Bell CM. How to use quality improvement tools in clinical practice: a primer for nephrologists. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(5):891–2.

Silver SA, McQuillan R, Harel Z, Weizman AV, Thomas A, Nesrallah G, Bell CM, Chan CT, Chertow GM. How to sustain change and support continuous quality improvement. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(5):916-24.

McQuillan RF, Silver SA, Harel Z, Weizman A, Thomas A, Bell C, et al. How to measure and interpret quality improvement data. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(5):908–14.

Silver SA, Harel Z, McQuillan R, Weizman AV, Thomas A, Chertow GM, et al. How to begin a quality improvement project. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(5):893–900.

Harel Z, Silver SA, McQuillan RF, Weizman AV, Thomas A, Chertow GM, et al. How to diagnose solutions to a quality of care problem. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(5):901–7.

Shojania KG, Grimshaw JM. Still no magic bullets: pursuing more rigorous research in quality improvement. Am J Med. 2004;116:778–80.

Oxman AD, Thomson MA, Davis DA, Haynes RB. No magic bullets: a systematic review of 102 trials of interventions to improve professional practice. Can Med Assoc J. 1995;153:1423–31.

Shojania KG, Grimshaw JM. Evidence-based quality improvement: the state of the science. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24:138–50.

Gagel BJ. Health Care Quality Improvement Program: a new approach. Health Care Financ Rev. 1995;16:15–23.

Helgerson SD, McClellan WM, Frederick PR, Beaver SK, Frankenfield DL, McMullan M. Improvement in adequacy of delivered dialysis for adult in-center hemodialysis patients in the United States, 1993 to 1995. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;29:851–61.

Wolfe RA, Hulbert-Shearon TE, Ashby VB, Mahadevan S, Port FK. Improvements in dialysis patient mortality are associated with improvements in urea reduction ratio and hematocrit, 1999 to 2002. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45:127–35.

Sehgal AR, Leon JB, Siminoff LA, Singer ME, Bunosky LM, Cebul RD. Improving the quality of hemodialysis treatment: a community-based randomized controlled trial to overcome patient-specific barriers. JAMA. 2002;287:1961–7.

McClellan WM, Hodgin E, Pastan S, McAdams L, Soucie M. A randomized evaluation of two health care quality improvement program (HCQIP) interventions to improve the adequacy of hemodialysis care of ESRD patients: feedback alone versus intensive intervention. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:754–60.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and ElaborationPRISMA: Explanation and Elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:W-65.

Mottes T, Owens T, Niedner M, Juno J, Shanley TP, Heung M. Improving delivery of continuous renal replacement therapy: impact of a simulation-based educational intervention. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14:747–54.

Elsayed E, El-Soreety W, Elawany T, Nasar F. Effect of nursing intervention on the quality of life of children undergoing hemodialysis. Life Sci J. 2012;9:77–86.

Fontanesi J, Mendoza S, Bowers D, Reznik V. Translating operational research to the medical community: using "guiding measurements" to improve the quality of healthcare delivery. J Med Pract Manage. 2009;24:248–53.

Mills M, White SC, Kershaw D, Flynn JT, Brophy PD, Thomas SE, et al. Developing clinical protocols for nursing practice: improving nephrology care for children and their families. Nephrol Nurs J. 2005;32:599–606. quiz 607.

Brown JR, Solomon RJ, Sarnak MJ, McCullough PA, Splaine ME, Davies L, et al. Reducing contrast-induced acute kidney injury using a regional multicenter quality improvement intervention. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7(5):693–700.

Kauric-Klein Z, Artinian N. Improving blood pressure control in hypertensive hemodialysis patients. CANNT J. 2007;17:24–8. 31-26; quiz 29-30, 37-28.

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. "About Us". http://www.pcori.org/about-us. Accessed 10 Nov 2016.

Jenkins, M. Getting Lean: Across the enterprise Boeing is attacking waste and streamlinig process. The goal? Cost competitiveness. Boeing Frontiers Online. 2002;1(4) http://www.boeing.com/news/frontiers/archive/2002/august/cover.html. Accessed 10 Nov 2016.

Fine BA, Golden B, Hannam R, Morra D. Leading lean: a canadian healthcare leader’s guide. Healthc Q. 2009;12(3):32–41.

Kenney C, Berwick D. Transforming Healthcare. Virginia Mason Medical Center's Pursuit of the Perfect Patient Experience. New York: Productivity Press. Taylor & Francis Group; 2011.

Liker J. The Toyota Way. 14 Management Principles for the World's Greatest Manufacturer. New York: McGraw Hill; 2004.

Easterbrook PJ, Gopalan R, Berlin JA, Matthews DR. Originally published as volume 1, issue 8746publication bias in clinical research. Lancet. 1991;337:867–72.

Forum Medical Advisory Council (MAC). The Forum of ESRD Networks. 2010 Quality Assessment and Performance Improvement (QAPI). http://esrdnetworks.org/resources/toolkits/mac-toolkits-1/qapi-toolkit/qapi-toolkit/view. Accessed 10 Nov 2016.

Smith KA, Hayward RA. Performance measurement in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:225–34.

van der Veer SN, Jager KJ, Nache AM, Richardson D, Hegarty J, Couchoud C, de Keizer NF, Tomson CRV. Translating knowledge on best practice into improving quality of RRT care: a systematic review of implementation strategies. Kidney Int. 2011;80:1021-34.

Schiller B. The medical director and quality requirements in the dialysis facility. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:493–9.

James MT, Hemmelgarn BR, Tonelli M. Early recognition and prevention of chronic kidney disease. Lancet. 2010;375:1296–309.

Eccles MP, Mittman BS. Welcome to implementation science. Implement Sci. 2006;1:1–1.

Zerhouni EA. Translational and clinical science — time for a new vision. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1621–3.

Lorch JA, Pollak VE. Continuous quality improvement in daily clinical practice: a proof of concept study. Plos One. 2014;9:e97066.

Majoni SW, Ellis JA, Hall H, Abeyaratne A, Lawton PD. Inflammation, high ferritin, and erythropoietin resistance in indigenous maintenance hemodialysis patients from the Top End of Northern Australia. Hemodial Int. 2014;18(4):740–50.

Nicholas J, Shaw C, Pitcher D, Dawnay A. UK renal registry 16th annual report: Chapter 12 biochemical variables amongst UK adult dialysis patients in 2012: National and centre-specific analyses. Nephron Clin Pract. 2014;125:219–58.

Wong LP, Yamamoto KT, Reddy V, Cobb D, Chamberlin A, Hien P, et al. Patient education and care for peritoneal dialysis catheter placement: a quality improvement study. Perit Dial Int. 2014;34:12–23.

Appleby S. Shared care, home haemodialysis and the expert patient. J Ren Care. 2013;39:16–21.

Chen LL. A preliminary review of the medication management service conducted by pharmacists in haemodialysis patients of Singapore General Hospital. Proceedings of Singapore Healthcare. 2013;22:103–6.

Chenoweth C. Reducing nursing needlestick injuries in haemodialysis clinics: a quality improvement program. RSAJ. 2013;9:22–6.

Esposito P, Benedetto AD, Tinelli C, De Silvestri A, Rampino T, Marcelli D, et al. Clinical audit improves hypertension control in hemodialysis patients. Int J Artif Organs. 2013;36:305–13.

Lewis S, White Y. Identification of unplanned activity in a regional home dialysis training unit. RSAJ. 2013;9:130–5.

Triamchaisri SK, Mawn BE, Artsanthia J. Development of a home-based palliative care model for people living with end-stage renal disease. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2013;15:E1–E11.

Weale AR, Study T. The safer clinical systems project in renal care. J Ren Care. 2013;Suppl 2:19–22.

Ball LK, Buss JA. Improving the fistula rate: the northwest renal network experience. Nephrol News Issues. 2012;26:22–3. 27-28, 30.

Josland E, Brennan F, Anastasious A, Brown MA. Developing and sustaining a renal supportive care service for people with end-stage kidney disease. RSAJ. 2012;8:11–7.

Parra E, Arenas MD, Alonso M, Martinez MF, Gamen A, Balda S, et al. Outcomes weighting for comprehensive haemodialysis centre assessment. Nefrologia. 2012;32:659–63.

Farrell A, Riley K, Wheeler S, McLean S. Application of critical thinking diagnostics in the renal setting. JRN. 2011;3:273–8.

Gardner J, Walton J. Striving to be heard and recognized: nurse solutions for improvement in the outpatient hemodialysis work environment. Nephrol Nurs J. 2011;38:239–53.

Hauser N, Anderson D, Stevenson JA, Kirschbaum SM, Wetzel P, Hannah K. A QIO-renal network collaboration experience: addressing care transitions. Remington Report. 2011;19:29–32.

Remon Rodriguez C, Quiros Ganga PL, Gonzalez-Outon J, del Castillo Gamez R, Garcia Herrera AL, Sanchez Marquez MG, et al. Recovering activity and illusion: the nephrology day care unit. Nefrologia. 2011;31:545–59.

Sledge R, Aebel-Groesch K, McCool M, Johnstone S, Witten B, Contillo M, et al. Part 2. The promise of symptom-targeted intervention to manage depression in dialysis patients: improving mood and quality of life outcomes. Nephrol News Issues. 2011;25:24–8. 30-21.

Bajo MA, Selgas R, Remon C, Arrieta J, Alvarez-Ude F, Arenas MD, et al. Scientific-technical quality and ongoing quality improvement plan in peritoneal dialysis. Nefrologia. 2010;30:28–45.

Heung M, Adamowski T, Segal JH, Malani PN. A successful approach to fall prevention in an outpatient hemodialysis center. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:1775–9.

Morton AR, Murphy S, Hirsch D, Leblanc M, Barre P, Lok C, et al. Development and utility of a multi-dimensional grid to assess individual mineral metabolism control in hemodialysis patients: A potential aid for therapeutic decision making? Hemodialysis international. Hemodial Int. 2010;14:200–10.

Hall L, Gore S, Witten B. Rehabilitation update: vocational rehabilitation: is your facility on track? Nephrol News Issues. 2009;23:5p.

Lu XH, Su CY, Sun LH, Chen W, Wang T. Implementing continuous quality improvement process in potassium management in peritoneal dialysis patients. J Ren Nutr. 2009;19:469–74.

Ookalkar AD, Joshi AG, Ookalkar DS. Quality improvement in haemodialysis process using FMEA. Int J Qual Reliab Manage. 2009;26:817–30.

Ridley J, Wilson B, Harwood L, Laschinger HK. Work environment, health outcomes and magnet hospital traits in the Canadian nephrology nursing scene. CANNT J. 2009;19:28–35.

Alcazar JM, Arenas MD, Alvarez-Ude F, Virto R, Rubio E, Maduell F, et al. Preliminary results of the Spanish Society of Nephrology multicenter study of quality performance measures: hemodialysis outcomes can be improved. Nefrologia. 2008;28:597–606.

Arenas MD, Alvarez-Ude F, Moledous A, Malek T, Gil MT, Soriano A, et al. Can we improve our results in hemodialysis? Setting quality objectives, feedback, and benchmarking. Nefrologia. 2008;28:397–406.

Bowe D. IV iron therapy and anemia management in patients on hemodialysis: benefits of a revised CQI strategy. Nephrol Nurs J. 2008;35:371–7. 394; quiz 378-379.

Burg G, da Silveira DD. Proposal of an environmental management model for nephrology services… World Congress of Nephrology Nursing, São Paulo, April 22 to April 25, 2007. Acta Paulista de Enfermagem. 2008;21:192–7.

Ball LK, Treat L, Riffle V, Scherting D, Swift L. A multi-center perspective of the Buttonhole Technique in the Pacific Northwest. Nephrol Nurs J. 2007;34:234–41.

Harwood L, Ridley J, Lawrence-Murphy JA, Spence-Laschinger HK, White S, Bevan J, et al. Nurses' perceptions of the impact of a renal nursing professional practice model on nursing outcomes, characteristics of practice environments and empowerment--Part I. CANNT J. 2007;17:22–9.

Holtby MA. Know how it works before you fix it: a data analysis strategy from an inpatient nephrology patient-flow improvement project. CANNT J. 2007;17:30–6.

Li M, Porter E, Lam R, Jassal SV. Quality improvement through the introduction of interdisciplinary geriatric hemodialysis rehabilitation care. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;50:90–7.

Nguyen VD, Lawson L, Ledeen M, Treat L, Buss J, Barclay C, et al. Successful multidisciplinary interventions for arterio-venous fistula creation by the Pacific Northwest Renal Network 16 vascular access quality improvement program. J Vasc Access. 2007;8:3–11.

Tranter S, Burns T, Dobson S, Graf E, Ng W, Martinez Y. Practice development in the hospital haemodialysis unit: improving calcium and phosphate management. RSAJ. 2007;3:61–4.

Chen M, Deng JH, Zhou FD, Wang M, Wang HY. Improving the management of anemia in hemodialysis patients by implementing the continuous quality improvement program. Blood Purif. 2006;24:282–6.

Hinton V, Fish M. A care pathway for the end of life in a renal setting. J Ren Care. 2006;32:160–3.

Nicholas P, Boys J, Best J. Queensland collaborative for healthcare improvement: a model for the development of performance measures and quality improvement processes in renal dialysis. RSAJ. 2006;2:16–20.

Tranter S, Martinez Y, Rayment G. A nurse-initiated iron management protocol for patients on hospital haemodialysis. RSAJ. 2006;2:30–2.

Wijnen E, Planken N, Keuter X, Kooman JP, Tordoir JH, de Haan MW, et al. Impact of a quality improvement programme based on vascular access flow monitoring on costs, access occlusion and access failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:3514–9.

Tigert J, Chaloner N, Scarr B, Webster K. Development of a pamphlet: introducing advance directives to hemodialysis patients and their families. CANNT J. 2005;15:20–4.

Sekkarie M. Increasing the placement of native veins arteriovenous fistulae--the role of access surgeons' education and profiling. Clin Nephrol. 2004;62:44–8.

Stoffel MP, Barth C, Lauterbach KW, Baldamus CA. Evidence-based medical quality management in dialysis--Part I: Routine implementation of QiN, a German quality management system. Clin Nephrol. 2004;62:208–18.

Rafiq M, McGovern A, Jones S, Harris K, Tomson C, Gallagher H, et al. Falls in the elderly were predicted opportunistically using a decision tree and systematically using a database-driven screening tool. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:877–86.

Tahir M, Hassan S, De Lusignan S, Shaheen L, Chan T, Dmitrieva O. Development of a questionnaire to evaluate practitioners' confidence and knowledge in primary care in managing chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 2014;15:73.

Schachter ME, Romann A, Djurdev O, Levin A, Beaulieu M. The British Columbia Nephrologists' Access Study (BCNAS) - a prospective, health services interventional study to develop waiting time benchmarks and reduce wait times for out-patient nephrology consultations. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:182-2369-2314-2182.

Hemmelgarn BR, Manns BJ, Straus S, Naugler C, Holroyd-Leduc J, Braun TC, et al. Knowledge translation for nephrologists: strategies for improving the identification of patients with proteinuria. J Nephrol. 2012;25:933–43.

Mukoro F, Sweeney G, Mathews B. Providing patients online access to their live test results: An evaluation of usage and usefulness. Proceedings of the IADIS International Conference e-Health 2012, EH 2012. MCCSIS. 2012;2012:45–52.

Allen AS, Forman JP, Orav EJ, Bates DW, Denker BM, Sequist TD. Primary care management of chronic kidney disease. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:386–92.

Bayliss EA, Bhardwaja B, Ross C, Beck A, Lanese DM. Multidisciplinary team care may slow the rate of decline in renal function. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:704–10.

Chaudhry A, Feest T. UK Renal Registry 13th Annual Report (December 2010): Chapter 14: enhancing access to UK Renal Registry data through innovative online data visualisations Nephron. Clin Pract. 2011;119 Suppl 2:c249–254.

Desrochers JF, Lemieux JP, Morin-Belanger C, Paradis FS, Lord A, Bell R, et al. Development and validation of the PAIR (Pharmacotherapy Assessment in Chronic Renal Disease) criteria to assess medication safety and use issues in patients with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58:527–35.

Garcia Garcia M, Valenzuela Mujica MP, Martinez Ocana JC, Otero Lopez MS, Ponz Clemente E, Lopez Alba T, et al. Results of a coordination and shared clinical information programme between primary care and nephrology. Nefrologia. 2011;31:84–90.

Khosla N, Gordon E, Nishi L, Ghossein C. Impact of a chronic kidney disease clinic on preemptive kidney transplantation and transplant wait times. Prog Transplant. 2010;20:216–20.

Neyhart CD, McCoy L, Rodegast B, Gilet CA, Roberts C, Downes K. A new nursing model for the care of patients with chronic kidney disease: the UNC Kidney Center Nephrology Nursing Initiative. Nephrol Nurs J. 2010;37:121–30. quiz 131.

Stoves J, Connolly J, Cheung CK, Grange A, Rhodes P, O'Donoghue D, et al. Electronic consultation as an alternative to hospital referral for patients with chronic kidney disease: a novel application for networked electronic health records to improve the accessibility and efficiency of healthcare. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19:e54.

Lee BJ, Forbes K. The role of specialists in managing the health of populations with chronic illness: the example of chronic kidney disease. BMJ (Clin Res ed). 2009;339:b2395.

Patwardhan MB, Matchar DB, Samsa GP, Haley WE. Opportunities for improving management of advanced chronic kidney disease. Am J Med Qual. 2008;23:184–92.

Patwardhan MB, Matchar DB, Samsa GP, Haley WE. Utility of the advanced chronic kidney disease patient management tools: case studies. Am J Med Qual. 2008;23:105–14.

Philipneri MD, Rocca Rey LA, Schnitzler MA, Abbott KC, Brennan DC, Takemoto SK, et al. Delivery patterns of recommended chronic kidney disease care in clinical practice: administrative claims-based analysis and systematic literature review. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2008;12:41–52.

Wintz R, Rosenthal B, Fadem SZ. The physician quality reporting initiative: a practical approach to implementing quality reporting. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2008;15:56–63.

Bissonnette J, Woodend K, Davies B, Stacey D, Knoll GA. Evaluation of a collaborative chronic care approach to improve outcomes in kidney transplant recipients. Clin Transplant. 2013;27:232–8.

Stamou SC, Camp SL, Reames MK, Skipper E, Stiegel RM, Nussbaum M, et al. Continuous quality improvement program and major morbidity after cardiac surgery. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:772–7.

Williams HF, Fallone S. CQI in the acute care setting: an opportunity to influence acute care practice. Nephrol Nurs J. 2008;35:515–22.

Richardson A, Reynolds C, Rodgers R. Utilizing audit to evaluate improvements in continuous veno-venous haemofiltration practices in intensive therapy unit. Nurs Crit Care. 2006;11:154–60.

Ahya SN, Barsuk JH, Cohen ER, Tuazon J, McGaghie WC, Wayne DB. Clinical performance and skill retention after simulation-based education for nephrology fellows. Semin Dial. 2012;25:470–3.

Dwyer A, Shelton P, Brier M, Aronoff G. A vascular access coordinator improves the prevalent fistula rate. Semin Dial. 2012;25:239–43.

Nicole AG, Tronchin DM. Indicators for evaluating the vascular access of users in hemodialysis. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2011;45:206–14.

Quinan P, Beder A, Berall MJ, Cuerden M, Nesrallah G, Mendelssohn DC. A three-step approach to conversion of prevalent catheter-dependent hemodialysis patients to arteriovenous access. CANNT J. 2011;21:22–33.

Arce JM, Hernando L, Ortiz A, Diaz M, Polo M, Lombardo M, et al. Designing a method to assess and improve the quality of healthcare in Nephrology by means of the Delphi technique. Nefrologia. 2014;34:158–74.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Eve Kerr, MD for her insight and suggestions in final editing of this manuscript. Dr. Mani is now affiliated with the University of North Carolina, University Libraries, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Funding

This work was supported by an NIH NIDDK K23-DK097183 (JWN). There are no conflicts of interest to report. A portion of the data presented in this manuscript was presented as a poster at the National Kidney Foundation 2015 Conference in Dallas, Texas.

Availability of data and material

Data supporting the results are reported in this article and additional information is available by contacting the corresponding author.

Authors’ contributions

Research idea and study design: JWN, FJS, PR, JS, NM, MH; data acquisition: NM; data analysis/interpretation: JWN, FJS, PR, JS, MH; analysis: JWN. Each author contributed important intellectual content drafting and/or revising the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Final (Report) analysis file QI in CKD 10 year. (PDF 97 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Nunes, J.W., Seagull, F.J., Rao, P. et al. Continuous quality improvement in nephrology: a systematic review. BMC Nephrol 17, 190 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-016-0389-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-016-0389-1