Abstract

Background

Socioeconomic characteristics may affect the outcomes of patients treated with peritoneal dialysis (PD). There are two major medical insurances in China: the New Cooperative Medical Scheme (NCMS), mainly for rural residents, and the Urban Employees’ Medical Insurance (UEMI). The aim of the present study was to assess the effect of medical insurance type on survival of patient undergoing PD.

Method

This was a prospective study in adult patients who underwent PD at the Wuhan No.1 Hospital between January 2008 and December 2013. Patients had received continuous ambulatory PD for >3 months. Patients were divided according to their medical insurance. Demographic and socioeconomic data, biochemical parameters and primary clinical outcomes including all-cause mortality, switch to hemodialysis and kidney transplantation were analyzed.

Result

There were 415 patients with UEMI and 149 with NCMS. Compared with UEMI, patients with NCMS were younger, and had shorter dialysis duration, smaller proportion of diabetic nephropathy, more severe anemia, and more frequent hyperphosphatemia and hyperuricemia. Total Kt/V, creatinine clearance and residual renal function were not different. There was no difference in technique survival (P > 0.05) between the two groups, but rural patients showed lower overall survival (P < 0.05). Multivariate analysis showed that NCMS was independently associated with lower survival (RR = 1.49; 95% CI = 1.04-2.15).

Conclusions

Medical insurance model is independently associated with PD patient survival.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The association between patient characteristics and clinical outcomes in patients treated with peritoneal dialysis (PD) are complex and multifactorial [1-3]. Previous studies have shown that characteristics such as lower income, lower education level and being female were associated with higher mortality in PD patients [4-6]. In addition, dialysis patients living in rural areas have higher mortality compared with urban residents [7]. On the other hand, the patient volume of the PD center, education level and the distance from the residence to the hospital are associated with peritonitis, the most important complication of PD [8,9]. In addition, black race, diabetes and advanced age are predictors of peritonitis occurrence [9,10]. Racial and insurance disparity may affect the choice of treatment for patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) [11]. However, another study has shown that the economic status was not independently associated with outcomes in a large multicenter Brazilian cohort [12].

Approximately of 50% of Chinese people lives in rural areas, and these areas are often underdeveloped and far from hospitals. A previous study has shown that living far from the PD unit was associated with shorter time to first peritonitis episode, but was independently predictive of higher rate of cure with antibiotics alone and trends to lower rates of catheter removal and permanent switch to hemodialysis (HD) [13]. Another study has shown that low personal income influenced all-cause and cardiovascular survival, and initial peritonitis in PD patients, whiles education level predicted all-cause survival only for patients living in underdeveloped regions [14].

In China, the two major medical insurance systems are the New Cooperative Medical Scheme (NCMS) for rural residents, and the Urban Employees’ Medical Insurance (UEMI) for urban patients. However, there are many disparities in the funding source, financing level and proportion of reimbursement between the two insurance systems [15]. Even if people participating in the NCMS are less likely to become impoverished, NCMS reimbursement policies are far from optimal, which may interfere with the choice of treatment and compliance [16]. However, there is no study about the association between disparities in medical insurance and PD outcomes in China.

The present study examined the association between insurance type and outcomes after initiation of PD in a large volume PD center. Results of the present study might provide a rationale for individualization and tailoring of the therapeutic approach, particularly for rural patients.

Methods

Participants

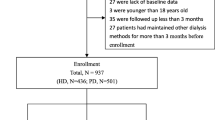

This was a prospective observational cohort study in all patients from the PD center of the Wuhan No.1 Hospital (Wuhan, China) receiving PD between January 2008 and December 2011. Patients were followed up until death or December 31st, 2013 (the end of the study), after which survival data were censored. Inclusion criteria were: 1) patients with ESRD; 2) aged 18-80 years; 3) received continuous ambulatory PD for more than 3 months; and 4) provided complete information about their socioeconomic status. Exclusion criteria were: 1) malignant disease; 2) refused to provide written consent; 3) unavailable or incomplete data about clinical and laboratory examination; or 4) the patient had no insurance. There is no automated PD in our center.

This study was approved by the ethical committee of the Wuhan No.1 Hospital and all participants provided a written informed consent.

Data collection

Data were obtained from patient records and medical staff reports. The demographic and socioeconomic data included family income, educational level (illiteracy, defined as less than elementary school, or literacy, defined as elementary school graduate or higher), etiology of chronic kidney disease (CKD), body mass index (BMI) and blood pressure (BP). Biochemical parameters including hemoglobin, serum albumin, serum creatinine, serum uric acid, albumin-corrected calcium, serum phosphorus and parathyroid hormone were measured at the central laboratory of the Wuhan No.1 Hospital. All biochemical parameters were measured at least yearly in all patients after PD treatments, and the average for each parameter was used in our analyses. Residual kidney function was assessed using glomerular filtration rate (GFR). Total Kt/V was calculated using the PD Adequest software 2.0 (Baxter, Deerfield, IL, USA). GFR, in ml/min/1.73 m2, was estimated from the mean values of creatinine clearance (CrCL) and urea clearance, and adjusted for body surface area [17].

Clinical outcomes

The primary clinical outcomes were all-cause mortality, switch to HD and kidney transplantation. Causes of death were grouped as: 1) cardiovascular death (myocardial infarction, cardiac arrest, heart failure, cerebrovascular accident, and other cardiac causes); 2) peritonitis-related mortality; 3) treatment withdrawal for financial reasons (gave up treatment if the family could not afford high medical expenses); and 4) other or unknown causes. Causes of switch to HD were grouped as: 1) peritonitis; 2) inadequate dialysis (including ultrafiltration failure and other medical causes); and 3) others (catheter-related complications or medical problems such as pleural effusions). For the purposes of this study, all outcomes data (survival, transplantation, withdrawal, technique failure, etc.) for all patients were censored on December 31st, 2013.

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD for normally distributed data, or as median and frequency (%) for non-normally distributed data. Categorical data are presented as proportions. Differences in demographics, clinical characteristics and laboratory parameters between the two groups were analyzed using the chi-square test for categorical data, and the unpaired t-test for normally distributed continuous data. Survival curves and survival probabilities were generated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Risk factors associated with mortality and technique failure were determined by multivariate Cox proportional hazards model. The covariates included in the Cox regression models were age (as a continuous variable), sex, education, insurance, BMI and laboratory data (listed in Table 1). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 17.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

A total of 564 patients were included: 415 (77.0%) with UEMI and 149 (23.0%) with NCMS. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 2. Compared with patients with UEMI, patients with NCMS were younger (51.9 ± 14.7 vs. 57.3 ± 13.2 years, P < 0.001), had a shorter dialysis duration (time from the first PD treatment to study recruitment; 22.8 ± 17.6 vs. 31.4 ± 25.8 months, P = 0.01), had a smaller proportion of diabetic nephropathy (DN) (6.0% vs. 16.1%, P = 0.02) and had a higher proportion of illiteracy (71.1% vs. 44.1%, P < 0.001). There was no difference in sex, BMI and systolic BP between the two groups.

Biochemical parameters

During follow-up, patients with NCMS showed lower iron levels (89.83 ± 23.98 vs. 95.19 ± 21.13 g/L, P = 0.01), higher phosphorus levels (1.81 ± 0.53 vs. 1.69 ± 0.52 mmol/L, P = 0.02), and lower calcium levels (2.06 ± 0.25 vs. 2.15 ± 0.25 mmol/L, P < 0.001) compared with patients with UEMI. There was no difference in albumin, creatinine, urea nitrogen and normalized protein catabolic rate (nPCR) between the two groups (Table 1).

PD prescription and adequacy data

During follow-up, despite rural patients having a smaller PD volume (6572 ± 1484 vs. 7228 ± 1546 ml, P < 0.001), comparison of adequacy data showed that total Kt/V and CrCL were not different, and that residual GFR was not different between the two groups (Table 2).

Clinical outcome

Among all patients, 173 (41.7%) patients with UEMI and 58 (38.9%) patients with NCMS ceased treatment before the end of the study. There was no difference in unadjusted death rates between groups on a univariate analysis. Death was the main cause of treatment cessation, and there was no significant difference between the two groups (21.9% vs. 26.2%, P = 0.29). However, switch to HD was less frequent in patients with NCMS (15.9% vs. 8.1%, P = 0.02). Patients with NCMS had a shorter time on therapy compared with patients with UEMI (27.4 ± 19.9 vs. 36.6 ± 25.7 months, P = 0.01; unadjusted data) (Table 3).

Predictors of technique failure

During follow-up, 78 patients switched to HD. Peritonitis was the main cause of technique failure in both groups, followed by inadequate dialysis. The distribution of different causes of technique failure was similar between the two groups (Table 4; unadjusted data).

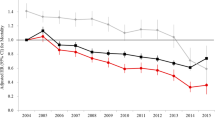

The technique survival rates at 1, 2, 3 and 5 years were 96.5%, 91.4%, 85.9% and 73.3%, respectively, for patients with NCMS, and 95.8%, 92.0%, 87.0% and 81.5%, respectively, for patients with UEMI (P = 0.245) (Figure 1). After adjustment for demographic and clinical characteristics, Cox model analysis showed that diabetic nephropathy (relative risk (RR) = 1.85, 95% confidence interval (95% CI): 1.10-3.13) and lower albumin (RR = 0.90, 95% CI: 0.86-0.94) were independent predictors of technique failure in all patients.

Patient survival and predictors of mortality

In the present study, patient survival according to insurance type was the primary outcome. Cardiovascular diseases were the main cause of death in both groups (25.6% vs. 35.2%, P = 0.29). Treatment withdrawal for financial reasons was more frequent in patients with NCMS compared with patients with UEMI (15.4% vs. 1.1%, P = 0.001) (Table 5). The unadjusted patient survival rate at 1, 2, 3 and 5 years were 94.0%, 81.1%, 73.0% and 58.4%, respectively, in patients with NCMS, and was 97.5%, 89.2%, 81.2% and 68.9%, respectively, in patients with UEMI. Kaplan-Meier analysis showed a higher survival in patients with UEMI (P < 0.05) (Figure 2). The relative risk of death for rural patients was 1.49 (95% CI, 1.04-2.15). Multivariate Cox regression analysis showed that education level, insurance type, age, albumin, serum phosphorus, peritoneal equilibration test and total Kt/V were independent predictors of patient survival in the combined cohort (Table 6).

Discussion

The present study was a prospective analysis of the relationship between clinical outcomes of PD and medical insurance model. Data showed that patients with NCMS had more severe anemia and hyperphosphatemia, and that survival was significantly lower in patients with NCMS compared with patients with UEMI. However, the technique failure rate was similar between the two groups.

Insurance disparity may affect the choice of treatment for patients with ESRD, as shown in the United States [11], South America [18] and Australia [19]. However, another study has shown that the economic status was not independently associated with outcomes in a large multicenter Brazilian cohort [12]. The primary outcome of the present study was to assess the association between insurance type and survival in PD patients, and results showed that PD patients with NCMS had a lower survival compared with PD patients with UEMI. Many factors might be responsible for this observation, such as education, nutrition, distance between home and hospital. Results of the present study are supported by a study from Columbia that showed that PD and hemodialysis patients with poor medical insurance coverage had lower survival [20]. Most importantly, the present study showed that the mortality due to financial reasons was higher in patients with NCMS compared with UEMI, underlining the importance of economics and insurance coverage in ESRD survival.

Previous studies in China showed that a high school education or higher was less frequent in rural areas and that the prevalence of CKD was higher compared with urban patients [21]. The present study showed that in accordance with their economic status, rural patient had a low education level. In addition, rural patients were younger, which might be related to a lower awareness of CKD, which may delay treatments in these patients and ultimately allow CKD to progress to ESRD.

Previous studies showed that Chinese rural patients have a lower proportion of hypertension and diabetes control [22,23]. In the present study, fewer rural patients suffered from diabetic nephropathy, and their diastolic BP control was inferior compared with urban patients, which is similar to previous epidemiological data from China [22,23].

Low hemoglobin levels, hyperphosphoremia, malnutrition and lower residual renal function are predictors of mortality in PD patients, and these predictors are independent from gender, race and dialysis buffer [6,24-26]. In our center, we observed that patient with NCMS had lower hemoglobin levels compared with patients with UEMI, which might be a consequence of malnutrition due to a lower economic status. In addition, these patients are less likely to be able to afford intravenous iron and erythropoiesis-stimulating agent therapy. Foods with high protein content are also an important source of dietary phosphorus [27]. However, even if patients with NCMS are able to consume high-protein foods, they usually are unable to afford phosphorus binders such as sevelamer carbonate and lanthanum carbonate. As a result, hyperphosphatemia was more common in rural patients even if albumin levels and nPCR were not significantly different between the two groups. Finally, we observed no difference on residual renal function between the two groups, and we presume that it may be related to the longer dialysis duration for patients with UEMI.

Studies have shown that mortality was higher among PD patients who lived farther from their attending nephrologist compared with patients who lived closer, which may be the result of less frequent contact with a nephrologist for patients in remote areas [28-30]. However, another study has shown that although the risk of death was significantly higher in remote dwellers, distance from the dialysis center and residing in rural areas did not affect the risk of technique failure or death [31]. In China, patients with NCMS mainly live in rural areas, which are often underdeveloped areas far from any hospital compared with patients with UEMI. They live farther from their treating center and have less contact with their physician. Dialysis inadequacy is an important predictor for mortality in PD patient, especially for anuric patients [32]. Studies have shown that a Kt/V <1.7 was associated with an increased risk of mortality and hospitalization, and that this observation persisted after multivariate adjustment [33]. The present study suggests that although the dialysis volume was lower in rural patients compared with urban patients, the Kt/V and CrCL were not different between the two groups, indicating that the different clinical outcomes were not associated with solute clearance.

Previous studies have shown that the main causes of switching from PD to HD were infections, fluid overload, abdominal surgery, malnutrition, decreased mental capacity and abdominal wall defect [34]. Despite a probable higher rate of malnutrition among rural patients compared urban patients, we did not observe any difference in the rate of switching to HD. This may be because the switching rate is affected by many factors, and because we did not assess all of them in the present study. Further studies are needed to assess this specific issue. Nevertheless, a likely explanation might be the lack of access to a HD facility in remote rural areas. As for the similarity in transplantation rate, the limited access to compatible donor kidneys might be a limiting factor that is more important than financial reasons.

Peritonitis is the most frequent cause of peritoneal dialysis failure, and significantly affects patient mortality [35]. However, it is a modifiable factor and the patients may be switched to hemodialysis [36]. In addition, a previous study has shown that living more than 100 km from a dialysis unit increased the risk of S. aureus peritonitis [13]. In the present study, data from patients with technique failure showed that peritonitis was the major cause of switching to hemodialysis, and that there was no difference between the two groups. Therefore, the higher rate of treatment cessation in patients with NCMS may be related to the lower survival. In addition, results showed that DN and hypoalbuminemia were independent predictors for technique failure.

This study has several limitations. First, data were from a single center and the sample was small, preventing extrapolation of the results to all Chinese patients with ESRD and to other countries. We did not evaluate the comorbidities and previous treatments at enrollment. We did not evaluate the distances between the patient, his family and the hospital. Finally, the cause of death for many patients had to be presumed by the nephrologist, especially for the patients who died at home.

Conclusions

In summary, biomedical parameters were inferior in patients with NCMS compared with patients with UEMI. Although the technique failure rate was similar between the two groups, survival was lower in patients with NCMS. Therefore, in light of our findings, we suggest that the medical coverage rate for patients with ESRD needs to be improved. Health policy makers should consider building satellite PD centers and developing PD networks to standardize the training programs. For the nephrologists, there is a need to reinforce targeted intervention for rural patients and to implement suitable treatments based on their economic status and insurance type.

Abbreviations

- BP:

-

Blood pressure

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- CrCL:

-

Creatinine clearance

- ESRD:

-

End-stage renal disease

- GFR:

-

Glomerular filtration rate

- HD:

-

Hemodialysis

- PD:

-

Peritoneal dialysis

- NCMS:

-

New Cooperative Medical Scheme

- UEMI:

-

Urban Employees’ Medical Insurance

References

Jolly SE, Burrows NR, Chen SC, Li S, Jurkovitz CT, Norris KC, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in mortality among individuals with chronic kidney disease: results from the Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP). Clin J American Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(8):1858–65.

Yan G, Norris KC, Yu AJ, Ma JZ, Greene T, Yu W, et al. The relationship of age, race, and ethnicity with survival in dialysis patients. Clin JAmerican Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(6):953–61.

Kucirka LM, Grams ME, Lessler J, Hall EC, James N, Massie AB, et al. Association of race and age with survival among patients undergoing dialysis. Jama. 2011;306(6):620–6.

Maripuri S, Arbogast P, Ikizler TA, Cavanaugh KL. Rural and micropolitan residence and mortality in patients on dialysis. Clin J American SocNephrol. 2012;7(7):1121–9.

Davenport A, Hussain Sayed R, Fan S. The effect of racial origin on total body water volume in peritoneal dialysis patients. Clin J American Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(10):2492–8.

Chung SH, Han DC, Noh H, Jeon JS, Kwon SH, Lindholm B, et al. Risk factors for mortality in diabetic peritoneal dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant Official Publication European Dial Transplant Assoc European Renal Assoc. 2010;25(11):3742–8.

Gray NA, Dent H, McDonald SP. Renal replacement therapy in rural and urban Australia. Nephrol Dial Transplant Official Publication European Dial Transplant Assoc European Renal Assoc. 2012;27(5):2069–76.

Bello AK, Hemmelgarn B, Lin M, Manns B, Klarenbach S, Thompson S, et al. Impact of remote location on quality care delivery and relationships to adverse health outcomes in patients with diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant Official Publication European Dial Transplant Assoc European Renal Assoc. 2012;27(10):3849–55.

Martin LC, Caramori JC, Fernandes N, Divino-Filho JC, Pecoits-Filho R, Barretti P, et al. Geographic and educational factors and risk of the first peritonitis episode in Brazilian Peritoneal Dialysis study (BRAZPD) patients. Clin J American Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(8):1944–51.

Nessim SJ, Bargman JM, Austin PC, Story K, Jassal SV. Impact of age on peritonitis risk in peritoneal dialysis patients: an era effect. Clin J American Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(1):135–41.

Johansen KL, Zhang R, Huang Y, Patzer RE, Kutner NG. Association of race and insurance type with delayed assessment for kidney transplantation among patients initiating dialysis in the United States. Clin J American Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(9):1490–7.

de Andrade Bastos K, Qureshi AR, Lopes AA, Fernandes N, Barbosa LM, Pecoits-Filho R, et al. Family income and survival in Brazilian Peritoneal Dialysis Multicenter Study Patients (BRAZPD): time to revisit a myth? Clin J American Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(7):1676–83.

Cho Y, Badve SV, Hawley CM, McDonald SP, Brown FG MNB, Wiggins KJ, et al. The effects of living distantly from peritoneal dialysis units on peritonitis risk, microbiology, treatment and outcomes: a multi-centre registry study. BMC Nephrol. 2012;13:41.

Xu R, Han QF, Zhu TY, Ren YP, Chen JH, Zhao HP, et al. Impact of individual and environmental socioeconomic status on peritoneal dialysis outcomes: a retrospective multicenter cohort study. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e50766.

Wagstaff A, Lindelow M. Can insurance increase financial risk? The curious case of health insurance in China. J Health Econ. 2008;27(4):990–1005.

Jing S, Yin A, Shi L, Liu J. Whether New Cooperative Medical Schemes reduce the economic burden of chronic disease in rural China. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e53062.

van Olden RW, Krediet RT, Struijk DG, Arisz L. Measurement of residual renal function in patients treated with continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996;7(5):745–50.

Organization PAH. Ministerio de Protección Social. Boletín Epidemiológico. PAHO: Bogota; 2006.

Grace BS, Clayton PA, Gray NA, McDonald SP. Socioeconomic differences in the uptake of home dialysis. Clin J American Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(5):929–35.

Sanabria M, Munoz J, Trillos C, Hernandez G, Latorre C, Diaz CS, et al. Dialysis outcomes in Colombia (DOC) study: a comparison of patient survival on peritoneal dialysis vs hemodialysis in Colombia. Kidney Int Suppl. 2008;108:S165–72.

Zhang L, Wang F, Wang L, Wang W, Liu B, Liu J, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in China: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2012;379(9818):815–22.

Wu Y, Huxley R, Li L, Anna V, Xie G, Yao C, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in China: data from the China National Nutrition and Health Survey 2002. Circulation. 2008;118(25):2679–86.

Yang W, Lu J, Weng J, Jia W, Ji L, Xiao J, et al. Prevalence of diabetes among men and women in China. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(12):1090–101.

Molnar MZ, Mehrotra R, Duong U, Kovesdy CP, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Association of hemoglobin and survival in peritoneal dialysis patients. Clin J American Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(8):1973–81.

Palmer SC, Hayen A, Macaskill P, Pellegrini F, Craig JC, Elder GJ, et al. Serum levels of phosphorus, parathyroid hormone, and calcium and risks of death and cardiovascular disease in individuals with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama. 2011;305(11):1119–27.

Perl J, Bargman JM. The importance of residual kidney function for patients on dialysis: a critical review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(6):1068–81.

Shinaberger CS, Greenland S, Kopple JD, Van Wyck D, Mehrotra R, Kovesdy CP, et al. Is controlling phosphorus by decreasing dietary protein intake beneficial or harmful in persons with chronic kidney disease? Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(6):1511–8.

Tonelli M, Manns B, Culleton B, Klarenbach S, Hemmelgarn B, Wiebe N, et al. Association between proximity to the attending nephrologist and mortality among patients receiving hemodialysis. Canadian Med Assoc J. 2007;177(9):1039–44.

Gray NA, Grace BS, McDonald SP. Peritoneal dialysis in rural Australia. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:278.

Tonelli M, Hemmelgarn B, Culleton B, Klarenbach S, Gill JS, Wiebe N, et al. Mortality of Canadians treated by peritoneal dialysis in remote locations. Kidney Int. 2007;72(8):1023–8.

Chidambaram M, Bargman JM, Quinn RR, Austin PC, Hux JE, Laupacis A. Patient and physician predictors of peritoneal dialysis technique failure: a population based, retrospective cohort study. Peritoneal Dial Int J Int Soc Peritoneal Dial. 2011;31(5):565–73.

Jansen MA, Termorshuizen F, Korevaar JC, Dekker FW, Boeschoten E, Krediet RT, et al. Predictors of survival in anuric peritoneal dialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2005;68(3):1199–205.

Fried L, Hebah N, Finkelstein F, Piraino B. Association of Kt/V and creatinine clearance with outcomes in anuric peritoneal dialysis patients. American J Kidney Dis Official J National Kidney Foundation. 2008;52(6):1122–30.

Jaar BG, Plantinga LC, Crews DC, Fink NE, Hebah N, Coresh J, et al. Timing, causes, predictors and prognosis of switching from peritoneal dialysis to hemodialysis: a prospective study. BMC Nephrol. 2009;10:3.

Davenport A. Peritonitis remains the major clinical complication of peritoneal dialysis: the London, UK, peritonitis audit 2002-2003. Peritoneal Dial Int J Int Soc Peritoneal Dial. 2009;29(3):297–302.

Perl J, Wald R, Bargman JM, Na Y, Jassal SV, Jain AK, et al. Changes in patient and technique survival over time among incident peritoneal dialysis patients in Canada. Clin J American Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(7):1145–54.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Wuhan Youth Chenguang Program of Science and Technology (No. 201150431083).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ZSW and YMZ carried out the study design, data collection and analysis, and wrote the manuscript. FX planned the study, participated in its design and coordination, and provided critical revision of the manuscript. HBL, YQD, YHG, LZ and SW participated in data collection and helped to perform the statistical analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Zengsi Wang and Yanmin Zhang contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Z., Zhang, Y., Xiong, F. et al. Association between medical insurance type and survival in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis. BMC Nephrol 16, 33 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-015-0023-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-015-0023-7