Abstract

Background

Joubert syndrome and related disorders (JSRD) is a clinically and genetically heterogeneous condition with autosomal recessive or X-linked inheritance, which share a distinctive neuroradiological hallmark, the so-called molar tooth sign. JSRD is classified into six clinical subtypes based on associated variable multiorgan involvement. To date, 21 causative genes have been identified in JSRD, which makes genetic diagnosis difficult.

Case presentation

We report here a case of a 28-year-old Japanese woman diagnosed with JS with oculorenal defects with a novel compound heterozygous mutation (p.Ser219*/deletion) in the NPHP1 gene. Whole-exome sequencing (WES) of the patient identified the novel nonsense mutation in an apparently homozygous state. However, it was absent in her mother and heterozygous in her father. A read depth-based copy number variation (CNV) detection algorithm using WES data of the family predicted a large heterozygous deletion mutation in the patient and her mother, which was validated by digital polymerase chain reaction, indicating that the patient was compound heterozygous for the paternal nonsense mutation and the maternal deletion mutation spanning the site of the single nucleotide change.

Conclusion

It should be noted that analytical pipelines that focus purely on sequence information cannot distinguish homozygosity from hemizygosity because of its inability to detect large deletions. The ability to detect CNVs in addition to single nucleotide variants and small insertion/deletions makes WES an attractive diagnostic tool for genetically heterogeneous disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Joubert syndrome and related disorders (JSRD) (OMIM 213300) is a rare neurological disorder with autosomal recessive or X-linked inheritance, characterized by neurological symptoms including hypotonia, ataxia, global developmental delay, abnormal eye movements, and breathing dysregulation [1–3]. JSRD is also often associated with visceral involvements and is classified into six clinical subtypes [2]. The neuroradiological hallmark of JSRD is the so-called molar tooth sign, which reflects a complex cerebellar and brainstem malformation [4, 5]. To date, 21 genes have been reported to be responsible for JSRD [1, 6]. JSRD has clinical and genetic heterogeneity, which makes it difficult to identify the causative mutations in individual cases by Sanger sequencing alone [7]. Whole-exome sequencing (WES) is becoming widely adopted as an efficient strategy to identify disease-causing mutations in genetically heterogeneous diseases. In addition to single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small insertion/deletions, structural changes such as copy number variations (CNVs) contribute to human diseases [8, 9]; however, the accurate detection of CNVs using WES data remains challenging. In this study, WES and a read depth-based CNV detection algorithm using WES data of the family identified not only a novel nonsense mutation but also a large heterozygous deletion mutation in NPHP1, leading to the precise molecular diagnosis of JSRD.

Case presentation

Clinical report

A 28-year-old Japanese woman who was diagnosed with JSRD and her family members (her parents and her healthy older sister) were involved in this study. The patient was referred to the neurology department for evaluation of her impaired walking and standing at the age of 28 years. She was the second child of non-consanguineous healthy parents (Fig. 1a). She had undergone a living-donor renal transplantation at 8 years of age. Her visual acuity had gradually decreased from infancy, leading to complete blindness. Ophthalmologic examination revealed no light perception in either eye. Neither blepharoptosis nor coloboma was observed. Funduscopic examination showed optic disc pallor. A neurological examination revealed truncal ataxia without apparent limb ataxia. Deep tendon reflexes were normal in all extremities and there were no pathological reflexes. Her Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III verbal IQ score was 75. The clinical symptoms of the patient were summarized in Additional file 1: Table S1. Axial brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed mildly thickened and elongated superior cerebellar peduncles, a deepened interpeduncular fossa, and vermian hypoplasia, resulting in the molar tooth sign (Fig. 1b). Based on MRI findings and clinical manifestations, the patient was diagnosed with JS with oculorenal defects.

a Pedigree of the family. Squares: males; circles: females. The filled circle represents the patient with Joubert syndrome and related disorders. b Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showing mildly thickened and elongated superior cerebellar peduncles (arrowheads), a deepened interpeduncular fossa (thin arrow), and vermian hypoplasia (thick arrow)

Molecular genetics

Genomic DNA was extracted from the peripheral blood of each subject using a DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). WES of the patient and her family members (her parents and her healthy older sister) was performed using amplicon-based next-generation sequencing. Briefly, libraries were constructed using an Ion AmpliSeq Library Kit v2.0 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantification of the libraries was performed by 2200 TapeStation Instrument using High Sensitivity D1000 Reagents and High Sensitivity D1000 ScreenTape (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Amplified libraries were submitted to emulsion polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using an Ion OneTouch™ 2 Instrument with an Ion PI™ Template OT2 200 Kit v3. Ion sphere particles were enriched using Ion OneTouch ES and were loaded on an Ion PI Chip v2. Sequencing was performed by Ion Proton™ with an Ion PI Sequencing 200 Kit v3. Read sequence files were then run through two independent pipelines constructed with Bowtie2 (http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/bowtie2/index.shtml)-GATK (the Genome Analysis Toolkit; https://www.broadinstitute.org/gatk/index.php) and BWA (Burrows Wheeler Alignment; http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/bwa.shtml)-Platypus (http://www.well.ox.ac.uk/platypus) to obtain variant call format files. Then, concordant genetic variants detected by two pipelines were annotated using ANNOVAR program (http://annovar.openbioinformatics.org). Then, variants in 21 known causative genes of JSRD were picked up. To calculate the depth of coverage, we used the GenomicRanges and IRanges packages from Bioconductor (http://www.bioconductor.org), with a sex-considered correction using the average read counts of the X chromosome in each sample, in consideration of the number of X chromosomes. Read counts of the patient were also compared with those of her father as a reference sample in the family. Then, we ran a hidden Markov model algorithm to call CNVs according to the programs described in the eXome Hidden Markov Model (XHMM) [10].

To confirm the mutation identified by WES, Sanger sequencing was performed by amplifying NPHP1 exon 7 with the following primers: 5′-AATTCCCATCTATGCTCAAGATTT-3′ (forward) and 5′-TTCCCACTTTTGTACCTTTGC-3′ (reverse). PCR products were sequenced using a BigDyeV3.1 terminator Kit on an ABI 310 automated sequencer (Life Technologies).

Digital PCR was performed on a QuantStudio™ 3D Digital PCR System (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, reaction mixtures were prepared with the QuantStudio 3D Digital PCR Master Mix and custom TaqMan probes. Primers for NPHP1 exon 7 (Hs00138437_cn) and BUB1 exon 8 (Hs02420021_cn) were purchased from Life Technologies. BUB1 is located 500 kb upstream of NPHP1 and was used as a control. Reaction mixtures were loaded onto a QuantStudio 3D Digital PCR Chip, and PCR was performed using recommended conditions. The gene copy number was analyzed using a QuantStudio 3D Digital PCR Instrument.

Because JSRD is a genetically heterozygous condition, we performed amplicon-based next-generation sequencing to determine the causative mutations. WES of the patient identified a novel c.656C > A mutation in exon 7 of NPHP1, leading to a nonsense mutation at position 219 (p.Ser219*), which was confirmed by Sanger sequencing (NM_000272.3) (Fig. 2a). This mutation was not detected in publicly available databases: Exome Variant Server (ESP6500; http://evs.gs.washington.edu), dbSNP 138 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), 1000 Genomes Profect (http://www.1000genomes.org), ExAC (The Exome Aggregation Consortium; http://exac.broadinstitute.org), and in-house exome sequencing data of 128 control subjects that was obtained using the analysis pipeline described above. Contrary to expectations, we could not detect the c.656C > A mutation in her mother, whereas her father was heterozygous for the mutation. We could not detect any other rare SNVs in the 21 JSRD-related genes in the patient or her family members.

a Electropherograms of DNA sequences from family member. Solid arrowhead indicates the c.656C > A mutation. Open arrowhead represents the single nucleotide polymorphism rs11675767. b Digital polymerase chain reaction targeted to NPHP1 and BUB1. The number of copies of NPHP1 (left panel), BUB1 (middle panel), and the copy number ratios of NPHP1 to BUB1 (right panel) are shown

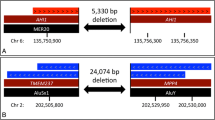

A deletion of NPHP1 had previously been reported in JSRD [11, 12], so we next performed CNV assessment using a read depth-based CNV detection algorithm. The CNV-calling algorithm predicted the presence of an approximately 470 kb heterozygous deletion including the entire NPHP1 gene in both the patient and her mother (Additional file 2: Figure S1). To confirm this deletion mutation, digital PCR targeted to NPHP1 exon 7 and BUB1 exon 8 was performed. The copy numbers of NPHP1 (copies/μl) in individuals I-1, I-2, II-1, and II-2 were 245.2, 133.6, 243.7, and 122.6, respectively (Fig. 2b, left panel). This compares with those of BUB1: 235.7, 231.0, 223.4, and 221.2, respectively (Fig. 2b, middle panel). The copy number ratios of NPHP1 to BUB1 of I-1, I-2, II-1, and II-2 were 1.04, 0.58, 1.09, and 0.55, respectively (Fig. 2b, right panel), indicating the presence of a heterozygous deletion in individuals I-2 (the patient’s mother) and II-2 (the patient). These findings indicated that the patient was compound heterozygous for the paternal nonsense mutation and the maternal deletion mutation.

Discussion

JSRD is a genetically heterogeneous disorder; therefore, the identification of the causative mutation for each patient by Sanger sequencing is a daunting task even after narrowing down the candidates based on clinical phenotype. As shown here, WES is also useful to detect not only single nucleotide changes but also CNVs that cannot be identified by Sanger sequencing. CNV assessment using WES data of the family led to the detection of a large deletion mutation in combination with a novel nonsense mutation of the remaining allele. In the present case, WES and Sanger sequencing of the patient detected the nonsense mutation in an apparently homozygous state; however, this was refuted by genetic testing to assess CNV. Therefore, it should be noted that analytical pipelines that focus purely on sequence information cannot distinguish homozygosity from hemizygosity because of its inability to detect large deletions. Thus, in this case, comprehensive analysis of the family was necessary to avoid imprecise genetic diagnosis.

CNV detection is an important issue in genetic diagnosis that might be overlooked by conventional sequencing strategies. Although several algorithms capable of identifying CNVs from WES data have been proposed, there is no WES-based CNV-calling method that can detect all CNVs in a large size range [13–15]. Because non-allelic homologous recombination between low-copy repeats on chromosome 2q13 have been shown to be a major cause of large deletions involving the NPHP1 gene [11, 16, 17], we chose to use XHMM based CNV-calling algorithm, which is suitable for predicting CNVs ranging from 10 kb to 1 Mb [13]. Although we have not determined the precise breakpoint of the deletion, the CNV-calling algorithm was nevertheless successful at predicting the heterozygous large deletion including the entire NPHP1 gene. It should be noted that WES data could identify not only SNVs but also clinically relevant CNVs without additional experiments such as genome-wide array comparative genomic hybridization or single nucleotide polymorphism array.

CNV validation methods include real-time quantitative PCR and multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification. In the present case, we performed chip-based digital PCR to confirm the NPHP1 deletion. This new PCR technique allows absolute quantification of copy numbers without reference to a standard curve, and produces precise results compared with conventional real-time quantitative PCR [18, 19]. We show that digital PCR is an alternative efficient method to confirm clinical relevant CNVs in genetic diagnosis.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we identified a novel compound heterozygous mutation (p.Ser219*/deletion) in the NPHP1 gene in a case of JSRD using WES. The present study showed a clinical usefulness of WES and digital PCR to detect clinically relevant CNVs in patients with genetically heterogeneous conditions. It should be noted that patients with genetic disorders might harbor CNVs that cannot be detected by conventional sequencing strategies.

Abbreviations

- CNV:

-

Copy number variation

- JSRD:

-

Joubert syndrome and related disorders

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- OMIM:

-

Online mendelian inheritance in man

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- SNV:

-

Single nucleotide variant

- WES:

-

Whole-exome sequencing

- XHMM:

-

eXome hidden markov model

References

Romani M, Micalizzi A, Valente EM. Joubert syndrome: congenital cerebellar ataxia with the molar tooth. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(9):894–905.

Brancati F, Dallapiccola B, Valente EM. Joubert Syndrome and related disorders. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:20.

Parisi MA. Clinical and molecular features of Joubert syndrome and related disorders. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2009;151C(4):326–40.

Maria BL, et al. "Joubert syndrome" revisited: key ocular motor signs with magnetic resonance imaging correlation. J. Child Neurol. 1997;12(7):423–30.

Poretti A, et al. Joubert syndrome and related disorders: spectrum of neuroimaging findings in 75 patients. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32(8):1459–63.

Valente EM, et al. Clinical utility gene card for: Joubert syndrome--update 2013. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013;21:10.

Tsurusaki Y, et al. The diagnostic utility of exome sequencing in Joubert syndrome and related disorders. J Hum Genet. 2013;58(2):113–5.

Cooper GM, et al. A copy number variation morbidity map of developmental delay. Nat Genet. 2011;43(9):838–46.

Pinto D, et al. Functional impact of global rare copy number variation in autism spectrum disorders. Nature. 2010;466(7304):368–72.

Fromer M, et al. Discovery and statistical genotyping of copy-number variation from whole-exome sequencing depth. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91(4):597–607.

Parisi MA, et al. The NPHP1 gene deletion associated with juvenile nephronophthisis is present in a subset of individuals with Joubert syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75(1):82–91.

Castori M, et al. NPHP1 gene deletion is a rare cause of Joubert syndrome related disorders. J Med Genet. 2005;42(2):e9.

Samarakoon PS, et al. Identification of copy number variants from exome sequence data. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:661.

Tan R, et al. An evaluation of copy number variation detection tools from whole-exome sequencing data. Hum Mutat. 2014;35(7):899–907.

Miyatake S, et al. Detecting copy-number variations in whole-exome sequencing data using the eXome Hidden Markov Model: an 'exome-first' approach. J Hum Genet. 2015;60(4):175–82.

Stankiewicz P, Lupski JR. Genome architecture, rearrangements and genomic disorders. Trends Genet. 2002;18(2):74–82.

Konrad M, et al. Large homozygous deletions of the 2q13 region are a major cause of juvenile nephronophthisis. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5(3):367–71.

Huggett JF, Whale A. Digital PCR as a novel technology and its potential implications for molecular diagnostics. Clin Chem. 2013;59(12):1691–3.

Nuzzo F, et al. Identification of a novel large deletion in a patient with severe factor V deficiency using an in-house F5 MLPA assay. Haemophilia. 2015;21(1):140–7.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patient and her family members who participated in this study. We are grateful to Ms. T. Seino for her technical assistance.

Funding

This report did not require any funding source.

Availability of data and materials

All data supporting our findings are included in the manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

SK acquired the clinical data. SK and HS carried out the molecular genetic studies. All authors analyzed data. SK wrote the initial draft of the manuscript which was edited by ME and TK. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s mother for publication of this Case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Yamagata University Faculty of Medicine. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient and her family members.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Clinical symptoms of the patient with Joubert syndrome with oculorenal defects in this study. (PPTX 85 kb)

Additional file 2: Figure S1.

Schematic presentation of the deletion mutation predicted by a read depth-based copy number variation detection algorithm. The approximately 470 kb heterozygous deletion including the entire NPHP1 gene is shown in the patient (II-2) and her mother (I-2). The chromosomal positions are based on NCBI build 37. (PDF 84 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Koyama, S., Sato, H., Wada, M. et al. Whole-exome sequencing and digital PCR identified a novel compound heterozygous mutation in the NPHP1 gene in a case of Joubert syndrome and related disorders. BMC Med Genet 18, 37 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12881-017-0399-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12881-017-0399-2