Abstract

Background

The incidence of high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV)-driven head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, in particular oropharyngeal cancers (OPC), is increasing in high-resource countries. Patients with HPV-induced cancer respond better to treatment and consequently have lower case-fatality rates than patients with HPV-unrelated OPC. These considerations highlight the importance of reliable and accurate markers to diagnose truly HPV-induced OPC.

Methods

The accuracy of three possible test strategies, i.e. (a) hrHPV DNA PCR (DNA), (b) p16(INK4a) immunohistochemistry (IHC) (p16), and (c) the combination of both tests (considering joint DNA and p16 positivity as positivity criterion), was analysed in tissue samples from 99 Belgian OPC patients enrolled in the HPV-AHEAD study. Presence of HPV E6*I mRNA (mRNA) was considered as the reference, indicating HPV etiology.

Results

Ninety-nine OPC patients were included, for which the positivity rates were 36.4%, 34.0% and 28.9% for DNA, p16 and mRNA, respectively. Ninety-five OPC patients had valid test results for all three tests (DNA, p16 and mRNA). Using mRNA status as the reference, DNA testing showed 100% (28/28) sensitivity, and 92.5% (62/67) specificity for the detection of HPV-driven cancer. p16 was 96.4% (27/28) sensitive and equally specific (92.5%; 62/67). The sensitivity and specificity of combined p16 + DNA testing was 96.4% (27/28) and 97.0% (65/67), respectively. In this series, p16 alone and combined p16 + DNA missed 1 in 28 HPV driven cancers, but p16 alone misclassified 5 in 67 non-HPV driven as positive, whereas combined testing would misclassify only 2 in 67.

Conclusions

Single hrHPV DNA PCR and p16(INK4a) IHC are highly sensitive but less specific than using combined testing to diagnose HPV-driven OPC patients. Disease prognostication can be encouraged based on this combined test result.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In high-resource countries, human papillomavirus (HPV)-driven head and neck squamous cell carcinoma represents an increasing health problem, particularly in cancers of the oropharyngeal region, including base of tongue and tonsils [1,2,3,4]. An estimated 20–40% of oropharyngeal cancers (OPC) is believed to be caused by HPV infection, and the large majority of them (> 80%) are due to HPV16 [2, 5]. Patients with HPV-induced cancers respond better to treatment and consequently have better survival than patients with HPV-unrelated OPC [6,7,8,9,10,11]. HPV-positive tumours, compared to the HPV-negative ones, are characterized by multiple molecular and clinic-pathological differences [12], which should be further investigated. These considerations highlight the importance of reliable and accurate markers, or marker combinations, to diagnose truly HPV-induced OPC and guiding patients’ risk-stratification.

The most widely applied detection method was based on PCR amplification of viral DNA to determine HPV-positivity. However, several independent studies have highlighted that PCR-based assays for the detection of HPV DNA are not sufficiently accurate to establish the viral causality [13,14,15,16,17]. These PCR-based methods are highly sensitive and can detect even a few DNA copies per sample, which might yield false-positive results mainly reflecting transient infections [18,19,20]. Additional markers, such as the presence of viral E6/E7 mRNA transcripts and p16(INK4a) expression as surrogates for HPV-induced transformation, allow a more accurate classification of HPV-driven head and neck cancers (HNC) [15, 21,22,23,24,25].

Nowadays, HPV E6/E7 oncogene transcript detection is considered the gold standard, for HPV-induced malignancies particularly depend on the carcinogenic potential of the HPV E6 and E7 oncoproteins [23, 26]. Nevertheless, viral transcript detection is laborious and may not be feasible everywhere in daily lab routine. This is particularly true for the detection of mRNA transcripts in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue specimens, which are commonly used during routine diagnostic work up; however, RNA integrity may be affected by the fixation protocol.

HPV E7 oncogenic signaling brings about substantial overexpression of the cellular protein p16(INK4a) in HPV-transformed cells [27]. Therefore, the immunohistochemical detection of p16(INK4a) overexpression is presently applied as a surrogate biomarker of HPV-transformed cervical epithelium [28,29,30]. Similarly, p16(INK4a) immunohistochemistry (IHC) is regularly used to establish HPV association in HNC [22, 23, 31,32,33]. Apart from single p16(INK4a) IHC, combined p16(INK4a) and HPV DNA detection by PCR is oftenly used.

HPV-AHEAD (FP7 funded network)

The HPV-AHEAD study (“Role of human papillomavirus infection and other co-factors in the aetiology of head and neck cancer in Europe and India”) group comprised partners from six European countries and from India (website HPV-AHEAD: https://hpv-ahead.iarc.fr/). The main goal of the study was to perform a comprehensive analysis on a large number of HNC cases to clarify pathogenic pathways in HNC carcinogenesis, and to identify clinically useful biomarkers.

In a previous publication [34], the results of the histological and molecular assessment of 1039 archived HNC specimens from Belgian patients were described, primarily using the detection of HPV DNA, mRNA, and p16(INK4a) IHC. In this study, we focus on the accuracy of these tests—individually and in combination—to diagnose hrHPV-driven oropharyngeal cancer.

Methods

Patient selection, clinical information and tissue specimen collection for the Belgian cohort

The overall study included patients with oropharyngeal, oral cavity, laryngeal, hypopharyngeal, and unspecified head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. For a detailed description of the patient characteristics, we refer to the previous publication of the Belgian HPV-AHEAD study data [34]. For the analyses in this study, the focus was on the oropharyngeal cancers [ICD-O-3 codes: C01 (base of tongue); C02.4 (lingual tonsil); C05.1 (soft palate); C05.2 (uvula); C09 (tonsil): C09.0, C09.1, C09.8 and C09.9; C10 (oropharynx): C10.0–10.4, C10.8 and C10.9].

FFPE tumour blocks and clinical information were collected from OPC patients treated in two Belgian hospitals (GZA and UZA), diagnosed between 1980 and 2010.

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethical Committees of ‘GZA hospitals’ (ref nb: BVDE/hp/2013/01.147), ‘UZA & UA (University of Antwerp)’ (ref nb: 11/47/362) and IARC, Lyon, France (ref nb: 11–30).

Preparation of tissue sections (University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium)

FFPE-tissue blocks were all processed at the UA laboratory of cell biology and histology, following the optimized HPV-AHEAD sectioning protocol [34, 35]. Briefly, minimal ten sections (S) were prepared from each FFPE block. The first (S1) and the last (S10) 5 µm sections were hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained for morphologic histology interpretation and used to check for the presence of tumour. S2 and S9 (5 µm) were used for p16(INK4a) IHC staining, while the 10 µm sections S3–5 and S6–8 were used for the extraction of RNA and DNA, respectively.

Histological review

All sections were re-evaluated by the HPV-AHEAD pathology review panel. The review was blinded with respect to the original local diagnosis. Only FFPE blocks where S1 and S10 H&E sections reflected squamous tumour tissue were included in the analysis [34].

HPV E6*I mRNA analysis (DKFZ, Heidelberg, Germany)

All OPC cases were analysed for the presence of: (i) HPV16 E6*I mRNA, and (ii) ubiquitin C (ubC) mRNA as a cellular mRNA positive control (housekeeping gene used for RNA quality control). OPC cases positive for DNA of a non-HPV16 genotype were additionally analysed for E6*I mRNA of the respective genotype. Specimens that were HPV E6*I and/or ubC mRNA-positive (RNA+) were considered RNA valid. Reverse Transcription-PCR was carried out using the QuantiTect Virus Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), as described in full in former HPV-AHEAD publications [34, 36]. The type-specific E6*I mRNA assays identifying transcripts of fourteen high-risk and six possible/probable high-risk HPV genotypes [37] were applied.

HPV DNA genotyping (IARC, Lyon, France)

HPV DNA genotypes were detected by a E7 type-specific multiplex genotyping (E7-MPG) assay, which combines multiplex PCR and bead-based Luminex technology (Luminex Corporation, Austin, TX), as previously described [38, 39]. Type specific-MPG uses HPV type-specific primers targeting the E7 region of thirteen high-risk and six possible/probable high-risk HPV genotypes (HPV 16, 18, 26, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59, 66, 68a and b, 70, 73 and 82), as well as two low-risk HPV genotypes (HPV 6 and 11). Two primers for amplification of the beta-globin (β-globin) gene were also included to control for the DNA quality of each specimen. A detailed description of the DNA extraction and further HPV genotyping test characteristics can be found in the previous publication on the Belgian HPV-AHEAD study [34]. Genotyping controls and DNA preparation were blindly analysed, and no sign of contamination of negative controls was detected during the laboratory work.

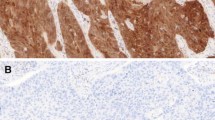

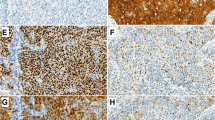

p16(INK4a) expression (Roche mtm laboratories, Mannheim, Germany)

Expression of p16(INK4a) was evaluated by IHC, with a dual-immunostaining protocol for the simultaneous immunostaining of both p16(INK4a) and Ki-67 biomarkers (CINtec PLUS kit, Roche mtm laboratories AG, Mannheim, Germany), as previously described in the HPV-AHEAD publications [34, 36]. As in all HPV-AHEAD studies [34, 36, 40], a continuous, diffuse staining for p16(INK4a) within the cancer area of the tissue sections was considered as positive, while a focal staining or no staining was considered negative. IHC slides were analysed without knowledge of any other clinical information (including HPV DNA and RNA status) by the scientists RR or DH and reviewed by one of the European members of the HPV-AHEAD pathology review panel (JPB, BLR, or FM). Discrepant cases were re-evaluated by a pathologist outside the review panel (AC), and final classification of the staining was based on majority consensus results.

Corresponding to the former Belgian HPV-AHEAD publication [34], the p16 slides with technical issues were restained and re-evaluated, to minimize the number of missing results.

Statistical analysis

Presence of viral mRNA was considered as the reference indicating HPV etiology. The accuracy of three possible test strategies was analysed: (a) hrHPV DNA PCR alone, (b) p16(INK4a) IHC alone, and (c) the combination of p16(INK4a) IHC and hrHPV DNA PCR; where positivity is defined by a co-positive result with both tests, a negative result by a co-negative result for both tests, and a discordant result by only one test being positive and the other being negative. Test strategy (c) involves three algorithms: ALGORITHM 1 (p16 + DNA) consists of p16(INK4a) IHC and hrHPV DNA PCR on all samples; ALGORITHM 2 (p16 → DNA) involves p16(INK4a) staining of all samples, followed by the HPV DNA test only on the p16(INK4a)-positive samples; ALGORITHM 3 (DNA → p16) involves HPV DNA PCR on all samples, followed by p16(INK4a) staining only on the HPV DNA-positive samples.

Sensitivity was defined as the proportion of test positive samples among HPV RNA-positive patients. Specificity was defined as the proportion of negative test results among HPV RNA-negative patients. Relative sensitivity and specificity of each test compared to the other tests were also assessed. Binomial 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were computed for proportions. Given the matched testing of the same patient specimens, McNemar 95% CIs were computed for relative accuracy parameters. Continuous variables were summarized by their mean and 95% CIs. ANOVA was used to compare mean age by gender.

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA 16 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). p-values were two sided and statistical significance was set at p equal or less than 0.05.

Results

Study population characteristics

Ninety-nine of 116 OPC patients were included in the analysis, after exclusions based on the pathology review (for reasons of not being a squamous cell carcinoma or not reflecting invasive cancer, N = 13) and beta-globin PCR negativity (N = 4). 71.7% (71/99) of the patients were male, 26.3% (26/99) were female, and for the remaining two samples the gender of the patients was not specified. The mean age at diagnosis was 67.3 years (95% CI 64.9–69.7) and was not different between males and females (p = 0.47).

HPV prevalence in OPC cases

HPV prevalence was determined by HPV DNA PCR, p16(INK4a) IHC, E6*I mRNA, and all combinations of tests in the HPV-AHEAD study. Out of 99 OPC cases, 36.4% (36/99) contained HPV DNA, 34.0% (33/97) showed p16(INK4a) positivity, and 28.9% (28/97) were HPV RNA-positive (Table 1). Twenty-six of the 28 HPV RNA-positive samples were positive for HPV16 (92.9%), the remaining 2 samples contained HPV18 (7.1%).

The proportion of HPV-positive OPCs varied between 28.4% (27/95) and 28.9% (28/97) for all combinations of tests that included RNA testing (DNA + RNA, p16 + RNA, DNA + p16 + RNA). For the combination of testing for HPV DNA and p16(INK4a) IHC, the overall prevalence was slightly higher (30.9%, 30/97).

Absolute and relative accuracy in the oropharynx and its subsites

Both absolute and relative accuracy of hrHPV DNA detection by PCR (hrHPV DNA), p16(INK4a) IHC (p16), and combined p16(INK4a) and DNA testing algorithms (p16 + DNA, p16 → DNA and DNA → p16), to identify a transforming HPV infection were calculated. In the following tables, only the results are shown for the samples that had valid results on all three tests performed (N = 95).

All RNA-positive OPC cases were positive for hrHPV DNA (100%, 28/28), in contrast to one out of 28 HPV RNA-positive samples that did not have a positive p16(INK4a) result (3.6%). Five out of 67 RNA-negative cases showed hrHPV DNA-positivity (7.5%), the same as observed for p16(INK4a) IHC. This number would be further lowered to only 2 positive cases out of 67 RNA-negatives (3.0%), if hrHPV DNA and p16(INK4a) testing (p16 + DNA) were combined. The same holds for the other algorithms where all samples would initially be tested on p16(INK4a) (p16 → DNA) or hrHPV DNA (DNA → p16), followed by the other test if the initial test result turned out positive. Data are detailed in Table 2, for all OPC cases, and for the tonsils and the base of tongue in specific. As the number of samples from other oropharyngeal subsites was very low, no relevant data can be shown.

The accuracy of hrHPV DNA PCR and p16(INK4a) IHC to detect a transforming HPV infection in OPCs was calculated (Table 3). Highest sensitivity (100.0%, 28/28) was noted for hrHPV DNA testing, while specificity was equal for both hrHPV DNA and p16(INK4a) (92.5%, 62/67). The best compromise was found in the combined testing of hrHPV DNA PCR and p16(INK4a) staining, with 96.4% (27/28) sensitivity and 97.0% (65/67) specificity. When looking in more detail to the proposed algorithms, all provided equal accuracy, however, with a 60% reduction in the number of HPV DNA PCR or p16(INK4a) IHC tests needed in the sequential testing algorithms.

For the subgroup of the tonsils, p16(INK4a) staining alone was as sensitive (94.7%, 18/19) and specific (91.3%, 21/23) as the combined testing, in contrast to the base of tongue group, where all tests were 100% sensitive and specific, except for the p16(INK4a) specificity (85.7%, 12/14).

hrHPV DNA PCR testing was slightly more sensitive compared to p16(INK4a) IHC (ratio: 1.04, 95% CI 0.97–1.11), but equally specific (ratio: 1.00, 95% CI not computable) (see Table 4 and Additional file 1: Table S1). The combination of hrHPV DNA and p16(INK4a) was slightly more specific (ratio: 1.05, 95% CI 0.97–1.21) compared to both single tests.

Discussion

In these Belgian OPC patients, PCR testing for HPV DNA showed 36% positive cases. This proportion lies somewhere between other published results from different parts of the world. Castellsagué et al. found a considerably lower prevalence of HPV DNA: 24.9% in OPC, in a large international series of 3,680 HNC biopsies [33]. A very similar proportion of HPV DNA-positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma of 35.6% was found by Kreimer et al. [19]. However, the meta-analysis of Ndiaye et al. showed a substantially higher prevalence up to 45.8% in OPC [17]. This worldwide overall prevalence is largely influenced by the very high prevalence in North America (60.4%), while the overall prevalence in Europe lands at 41.4%. The differences can probably be explained, in part, by the differences in the geographic origin of the samples, as well as the high heterogeneity in laboratory procedures and assays used in the various studies.

Due to its high sensitivity, HPV DNA PCR-based assays can detect low viral copy numbers, which may not trigger carcinogenesis. These assays cannot distinguish between transcriptionally-active and passenger HPV infections. Therefore, other assays (HPV E6*I mRNA, and p16(INK4a) staining) were evaluated to assess whether combined testing could improve the specificity. Only 28% of the samples with a valid HPV E6*I mRNA result were positive for HPV DNA and p16(INK4a), which might be the fraction of oropharyngeal cancers caused by HPV. After all, the detection of HPV E6 and/or E7 mRNA is seen as the gold standard in this context, because HPV-driven carcinomas critically depend on the continuous expression of E6/E7 oncogenes of hrHPVs [23, 26, 41]. However, the detection of viral transcripts is challenging, not only because the RNA extraction step is laborious and time consuming, but specific infrastructures and equipment are needed. Therefore, HPV RNA assays may not be routinely feasible in all laboratories or on all tissue samples.

HPV-driven OPC represents an increasing health problem, and therefore, reliable and accurate diagnosis becomes essential. In our Belgian HPV-AHEAD study, HPV DNA PCR testing alone was 100% sensitive, but less specific (92.5%) compared to mRNA testing. The inherent strength of the PCR-based methodology lies in its capacity to detect very small amounts of HPV DNA. At the same time, strict laboratory procedures and controls are critical in reducing contamination-related false-positive findings [42]. Immunohistochemistry for p16(INK4a) is most widely used as a surrogate marker for hrHPV infection in FFPE tissues, also for oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. p16(INK4a) IHC testing alone was a bit less sensitive (96.4%), but co-presence of hrHPV DNA and p16(INK4a) positivity was similarly sensitive (96.4%) and more specific (97.0%) compared to each test separately. In literature, several authors have advocated against the use of either p16(INK4a) or hrHPV DNA alone as indicators of HPV-induced etiology in cancers, but recommended their combined use as a reliable and practical approach to differentiate HPV-induced from HPV-unrelated tumours [26, 43,44,45]. The meta-analysis performed by Prigge et al. [46] also showed a similarly high (pooled) sensitivity of the combined testing (93%) and either p16(INK4a) (94%) or HPV DNA (98%) alone, and the (pooled) specificity (96%) was significantly higher than either testing method alone (83% and 84%, respectively). These accuracy data were confirmed by these Belgian results.

Relative sensitivities and specificities were not significantly different from unity in our study, nor in the meta-analysis of Prigge et al. [46], where significance was only reached for the relative specificity of the combination of HPV DNA PCR and p16(INK4a) tests versus p16(INK4a) IHC [rel. spec.: 1.13 (95% CI 1.04–1.23)], by pooling from multiple studies.

Furthermore, better clinical outcomes have been reported for patients with HPV-induced compared to HPV-unrelated OPC [6,7,8,9,10,11]. HPV-positive OPC patients show better age-standardised survival than HPV-negative counterparts, leading to investigation of de-intensified therapies to improve their quality of life. However, recent trials have shown worse survival outcomes [47,48,49]. Therefore, it is crucial to further characterize the molecular mechanisms defining HPV-driven OPC in order to identify novel prognostic markers and, in a more distant future, probable targets for more tailored and effective therapies for this subtype of OPC patients, with a therapeutic success at least equal or improved compared to current treatment regimens.

Improved prognostication by combined p16(INK4a) and hrHPV DNA detection compared to single marker analysis has been demonstrated in a large meta-analysis on tumours in the head and neck region [50]. In our study, 97% (92/95) of the patients would have been correctly diagnosed with the combined testing approach. However, one 58-year old male (current smoker and alcohol consumer) with a T1 (N0 M0) microinvasive tonsillar tumour might have been considered spuriously as having a bad prognosis by applying this combined test strategy, as his tumour would have been classified as a HPV-unrelated case, being p16(INK4a) negative while actually both DNA and mRNA HPV16 positive. More than six years after diagnosis, the patient was alive without any evidence of disease.

On the other hand, disease-specific survival rates are not improved among HPV DNA-positives where HPV is not the cause of carcinogenesis. In our series of 95 Belgian OPC patients, the number of false positive cancers would be reduced from five to two with the combined p16 + DNA detection. The two HPV-unrelated cancer patients were male and diagnosed with a tonsillar cancer. The first patient, with a Tx N2 M1 tonsil NOS tumour, was a heavy drinker and current smoker who only underwent surgery and had a recurrence within 6 months. He died 2 years after being diagnosed. The other patient, with a T3 N2 tonsil NOS tumour, received surgery followed by radiotherapy and concurrent chemotherapy for 2 months. At the last follow-up date, this patient was alive, but with evidence of residual disease. Of note, these two HPV-unrelated patients clearly had a much worse disease status at diagnosis and thereby reduced survival chances compared to the above described HPV-driven tonsillar cancer patient.

Ninety-seven percent of the OPC patients in our study would have been correctly diagnosed as patients with a HPV-driven cancer by combined p16(INK4a) and hrHPV DNA (p16 + DNA) detection. Sequential testing algorithms (p16 → DNA and DNA → p16) resulted in equally accurate results, however, with a 60% reduction in the number of tests needed to be performed. This will cause a substantial reduction in costs and laboratory time, while providing the same clinical value. Especially the algorithm of p16(INK4a) on all samples followed by HPV DNA PCR on p16(INK4a)-positive samples only would be a practical strategy. After all, p16(INK4a) IHC can easily be combined with standard histology when a H&E-stained tissue section is prepared for examination by a pathologist. It is a routine diagnostic procedure, at a relatively low cost, available as a validated in-vitro diagnostic reagent and a fully automated protocol, which generates results within several hours after the procedure has been requested. HPV DNA PCR is also a standard laboratory procedure with high throughput and quick results, although against a higher cost. Preselection by p16(INK4a)-staining therefore reduces the workload and associated costs, and the combination of HPV DNA and p16(INK4a) testing leads to an important reduction of the number of false-positive observations versus the use of either of these assays alone.

Limitations

The limited number of OPC cases and the respective anatomical subsites present in this cohort could have influenced the precision of the accuracy. However, more studies will emerge from the HPV-AHEAD consortium and a new updated meta-analysis on diagnostic accuracy of p16(INK4a) immunohistochemistry in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas is planned (which will include all studies from the meta-analysis by Prigge et al. [46], several HPV-AHEAD datasets and studies identified from the literature published after the meta-analysis of Prigge). A fine anatomical sub-classification can be incorporated as covariate, which hopefully yields statistical power.

Conclusions

In conclusion, combined testing for hrHPV DNA and p16(INK4a) enhances specificity up to 97%, while maintaining high sensitivity (96%), compared to single testing. The diagnostic test combination represents an accurate and accessible testing strategy in the clinical setting for diagnosis of HPV-induced OPC (especially for base of tongue and tonsillar cancers), allowing discriminant prognostication.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- FFPE:

-

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded

- H&E:

-

Hematoxylin and eosin

- HNC:

-

Head and neck cancers

- HPV:

-

Human papillomavirus

- hrHPV:

-

High-risk human papillomavirus

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry

- OPC:

-

Oropharyngeal cancer

- p16:

-

p16(INK4a)

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- RNA+:

-

mRNA-positive

- S:

-

Section

- ubC:

-

Ubiquitin C

References

Gillison ML, Castellsague X, Chaturvedi A, Goodman MT, Snijders P, Tommasino M, et al. Comparative epidemiology of HPV infection and associated cancers of the head and neck and cervix. Int J Cancer. 2014;134(3):497–507.

Arbyn M, de Sanjose S, Saraiya M, Sideri M, Palefsky JM, Lacey C, et al. EUROGIN 2011 roadmap on prevention and treatment of HPV-related disease. Int J Cancer. 2012;131(9):1969–82.

Jemal A, Simard EP, Dorell C, Noone AM, Markowitz LE, Kohler B, et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975–2009, featuring the burden and trends in human papillomavirus (HPV)-Associated Cancers and HPV Vaccination Coverage Levels. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:175–201.

Chaturvedi AK, Anderson WF, Lortet-Tieulent J, Curado MP, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, et al. Worldwide trends in incidence rates for oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4550–9.

De Martel C, Georges D, Bray F, Ferlay J, Clifford GM. Global burden of cancer attributable to infections in 2018: a worldwide incidence analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(2):e180–90.

Dayyani F, Etzel CJ, Liu M, Ho CH, Lippman SM, Tsao AS. Meta-analysis of the impact of human papillomavirus (HPV) on cancer risk and overall survival in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC). Head Neck Oncol. 2010;2:15.

Klussmann JP, Mooren JJ, Lehnen M, Claessen SM, Stenner M, Huebbers CU, et al. Genetic signatures of HPV-related and unrelated oropharyngeal carcinoma and their prognostic implications. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(5):1779–86.

Ragin CC, Taioli E. Survival of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck in relation to human papillomavirus infection: review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(8):1813–20.

Fakhry C, Westra WH, Li S, Cmelak A, Ridge JA, Pinto H, et al. Improved survival of patients with human papillomavirus-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in a prospective clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(4):261–9.

O’Rorke MA, Ellison MV, Murray LJ, Moran M, James J, Anderson LA. Human papillomavirus related head and neck cancer survival: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Oncol. 2012;48(12):1191–201.

Masterson L, Moualed D, Liu ZW, Howard JE, Dwivedi RC, Tysome JR, et al. De-escalation treatment protocols for human papillomavirus-associated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of current clinical trials. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50(15):2636–48.

Dok R, Nuyts S. HPV positive head and neck cancers: molecular pathogenesis and evolving treatment strategies. Cancers (Basel). 2016;8(4):41.

Halec G, Holzinger D, Schmitt M, Flechtenmacher C, Dyckhoff G, Lloveras B, et al. Biological evidence for a causal role of HPV16 in a small fraction of laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:172–83.

Jung AC, Briolat J, Millon R, de Reyniès A, Rickman D, Thomas E, et al. Biological and clinical relevance of transcriptionally active human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in oropharynx squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2010;126(8):1882–94.

Holzinger D, Schmitt M, Dyckhoff G, Benner A, Pawlita M, Bosch FX. Viral RNA patterns and high viral load reliably define oropharynx carcinomas with active HPV16 involvement. Cancer Res. 2012;72(19):4993–5003.

Chernock RD, Wang X, Gao G, Lewis JS Jr, Zhang Q, Thorstad WL, et al. Detection and significance of human papillomavirus, CDKN2A(p16) and CDKN1A(p21) expression in squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx. Mod Pathol. 2013;26(2):223–31.

Ndiaye C, Mena M, Alemany L, Arbyn M, Castellsague X, Laporte L, et al. HPV DNA, E6/E7 mRNA, and p16INK4a detection in head and neck cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(12):1319–31.

Gillison ML, Koch WM, Capone RB, Spafford M, Westra WH, Wu L, et al. Evidence for a causal association between human papillomavirus and a subset of head and neck cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(9):709–20.

Kreimer AR, Clifford GM, Boyle P, Franceschi S. Human papillomavirus types in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas worldwide: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(2):467–75.

Ha PK, Pai SI, Westra WH, Gillison ML, Tong BC, Sidransky D, et al. Real-time quantitative PCR demonstrates low prevalence of human papillomavirus type 16 in premalignant and malignant lesions of the oral cavity. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(5):1203–9.

Anantharaman D, Gheit T, Waterboer T, Abedi-Ardekani B, Carreira C, McKay-Chopin S, et al. Human papillomavirus infections and upper aero-digestive tract cancers: the ARCAGE study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(8):536–45.

Jordan RC, Lingen MW, Perez-Ordonez B, He X, Pickard R, Koluder M, et al. Validation of methods for oropharyngeal cancer HPV status determination in US cooperative group trials. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36(7):945–54.

Smeets SJ, Hesselink AT, Speel EJ, Haesevoets A, Snijders PJ, Pawlita M, et al. A novel algorithm for reliable detection of human papillomavirus in paraffin embedded head and neck cancer specimen. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(11):2465–72.

Rietbergen MM, Snijders PJ, Beekzada D, Braakhuis BJ, Brink A, Heideman DA, et al. Molecular characterization of p16-immunopositive but HPV DNA-negative oropharyngeal carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 2014;134(10):2366–72.

Shi W, Kato H, Perez-Ordonez B, Pintilie M, Huang S, Hui A, et al. Comparative prognostic value of HPV16 E6 mRNA compared with in situ hybridization for human oropharyngeal squamous carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(36):6213–21.

von Knebel Doeberitz M. The causal role of human papillomavirus infections in non-anogenital cancers. It’s time to ask for the functional evidence. Int J Cancer. 2016;139(1):9–11.

McLaughlin-Drubin ME, Crum CP, Munger K. Human papillomavirus E7 oncoprotein induces KDM6A and KDM6B histone demethylase expression and causes epigenetic reprogramming. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(5):2130–5.

Klaes R, Friedrich T, Spitkovsky D, Ridder R, Rudy W, Petry U, et al. Overexpression of p16(INK4A) as a specific marker for dysplastic and neoplastic epithelial cells of the cervix uteri. Int J Cancer. 2001;92(2):276–84.

Bergeron C, Ronco G, Reuschenbach M, Wentzensen N, Arbyn M, Stoler M, et al. The clinical impact of using p16(INK4a) immunochemistry in cervical histopathology and cytology: an update of recent developments. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(12):2741–51.

Roelens J, Reuschenbach M, von Knebel-Doeberitz M, Wentzensen N, Bergeron C, Arbyn M. p16INK4a immunocytochemistry versus HPV testing for triage of women with minor cytological abnormalities: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer. 2012;120(5):294–307.

Klussmann JP, Gultekin E, Weissenborn SJ, Wieland U, Dries V, Dienes HP, et al. Expression of p16 protein identifies a distinct entity of tonsillar carcinomas associated with human papillomavirus. Am J Pathol. 2003;162(3):747–53.

Prigge ES, Toth C, Dyckhoff G, Wagner S, Müller F, Wittekindt C, et al. p16(INK4a) /Ki-67 co-expression specifically identifies transformed cells in the head and neck region. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(7):1589–99.

Castellsague X, Alemany L, Quer M, Halec G, Quiros B, Tous S, et al. HPV involvement in head and neck cancers: comprehensive assessment of biomarkers in 3680 patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108(6):1.

Simoens C, Gorbaslieva I, Gheit T, Holzinger D, Lucas E, Ridder R, et al. HPV DNA genotyping, HPV E6*I mRNA detection, and p16(INK4a)/Ki-67 staining in Belgian head and neck cancer patient specimens, collected within the HPV-AHEAD study. Cancer Epidemiol. 2021;72: 101925.

Mena M, Lloveras B, Tous S, Bogers J, Maffini F, Gangane N, et al. Development and validation of a protocol for optimizing the use of paraffin blocks in molecular epidemiological studies: The example from the HPV-AHEAD study. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(10): e0184520.

Gheit T, Anantharaman D, Holzinger D, Alemany L, Tous S, Lucas E, et al. Role of mucosal high-risk human papillomavirus types in head and neck cancers in central India. Int J Cancer. 2017;141(1):143–51.

Halec G, Schmitt M, Dondog B, Sharkhuu E, Wentzensen N, Gheit T, et al. Biological activity of probable/possible high-risk human papillomavirus types in cervical cancer. Int J Cancer. 2013;132(1):63–71.

Gheit T, Landi S, Gemignani F, Snijders PJ, Vaccarella S, Francheschi S, et al. Development of a sensitive and specific assay combining multiplex PCR and DNA microarray primer extension to detect high-risk mucosal human papillomavirus types. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(6):2025–31.

Schmitt M, Bolormaa D, Waterboer T, Pawlita M, Tommasino M, Gheit T. Abundance of multiple high-risk human papillomavirus (hpv) infections found in cervical cells analyzed by use of an ultrasensitive HPV genotyping assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48(1):143–9.

Tagliabue M, Mena M, Maffini F, Gheit T, Quiros Blasco B, Holzinger D, et al. Role of human papillomavirus infection in head and neck cancer in Italy: the HPV-AHEAD study. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(12):1–7.

Johansson H, Bjelkenkrantz K, Darlin L, Dilllner J, Forslund O. Presence of high-risk HPV mRNA in relation to future high-grade lesions among high-risk HPV DNA positive women with minor cytological abnormalities. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(4):e0124460.

Victor T, Jordaan A, du Toit R, Van Helden PD. Laboratory experience and guidelines for avoiding false positive polymerase chain reaction results. Eur J Clin Chem Clin Biochem. 1993;31(8):531–5.

de Sanjose S, Alemany L, Ordi J, Tous S, Alejo M, Bigby SM, et al. Worldwide human papillomavirus genotype attribution in over 2000 cases of intraepithelial and invasive lesions of the vulva. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(16):3450–61.

Orosco RK, Califano JA. HPV status, like politics, is local-evaluating p16 staining and a new staging system in a Dutch cohort of oropharynx cancer. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(5):1089–90.

Wagner S, Prigge ES, Wuerdemann N, Reder H, Bushnak A, Sharma SJ, et al. Evaluation of p16(INK4a) expression as a single marker to select patients with HPV-driven oropharyngeal cancers for treatment de-escalation. Br J Cancer. 2020;123(7):1114–22.

Prigge ES, Arbyn M, von Knebel DM, Reuschenbach M. Diagnostic accuracy of p16(INK4a) immunohistochemistry in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2017;140(5):1186–98.

Oosthuizen JC, Doody J. De-intensified treatment in human papillomavirus-positive oropharyngeal cancer. Lancet. 2019;393(10166):5–7.

Gillison ML, Trotti AM, Harris J, Eisbruch A, Harari PM, Adelstein DJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab or cisplatin in human papillomavirus-positive oropharyngeal cancer (NRG Oncology RTOG 1016): a randomised, multicentre, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10166):40–50.

Mehanna H, Robinson M, Hartley A, Kong A, Foran B, Fulton-Lieuw T, et al. Radiotherapy plus cisplatin or cetuximab in low-risk human papillomavirus-positive oropharyngeal cancer (De-ESCALaTE HPV): an open-label randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10166):51–60.

Albers AE, Qian X, Kaufmann AM, Coordes A. Meta analysis: HPV and p16 pattern determines survival in patients with HNSCC and identifies potential new biologic subtype. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):16715.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful for the excellent work performed by Sofie Thys (University of Antwerp, Laboratory of cell biology and histology), for her meticulous work in preparing FFPE slide sections and logistical coordination and support of the study. Where authors are identified as personnel of the International Agency for Research on Cancer/World Health Organization, the authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the decisions, policy, or views of the International Agency for Research on Cancer/World Health Organization.

‘HPV-AHEAD study group’: Christine Carreira3, Sandrine McKay-Chopin3, Rudrapatna S. Jayshree12, Kortikere S. Sabitha12, Ashok M. Shenoy12, Alfredo Zito14, Fausto Chiesa15, Marta Tagliabue15, Mohssen Ansarin15, Subha Sankaran17, Christel Herold-Mende21,22, Gerhard Dyckhoff22, George Mosialos23, Heiner Boeing24, Xavier Castellsagué25†, Silvia de Sanjosé25, Marisa Mena25, Francesc Xavier Bosch25, Laia Alemany25, Pulikottil Okkuru Esmy26, Manavalan Vijayakumar27, Aruna S. Chiwate28, Ranjit V. Thorat28, Girish G. Hublikar28, Shashikant S. Lakshetti28, Bhagwan M. Nene28, Amal Ch Kataki29, Ashok Kumar Das29, Kunnambath Ramadas30, Thara Somanathan30

3Early Detection, Prevention and Infections Branch, International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); Lyon; France; 12Kidwai Memorial Institute of Oncology; Bangalore, Karnataka; India; 14IRCCS Istituto Tumori "Giovanni Paolo II"; Bari; Italy; 15Division of Pathology, IEO, European Institute of Oncology IRCCS; Milan; Italy; 17Rajiv Gandhi Centre for Biotechnology; Poojappura, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala; India; 21Department of Neurosurgery, Head and Neck Surgery, University of Heidelberg; Germany; 22Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, University of Heidelberg; Germany; 23Aristotle University of Thessaloniki; Greece; 24German Institute of Human Nutrition; Berlin; Germany; 25Catalan Institute of Oncology, IDIBELL, L'Hospitalet de Llobregat; Spain; 26Christian Fellowship Community Health Centre; Ambillikai; India; 27YEN ONCO Centre, Yenepoya University, Deralakatte, Mangalore 575018: Karnataka; India; 28Nargis Dutt Memorial Cancer Hospital; Barshi; India; 29Dr B. Borooah Cancer Institute, Guwahati; Assam; India; 30Regional Cancer Centre; Thiruvananthapuram; India. Dr. Castellsagué passed away on June 12th, 2016.

Funding

The global HPV-AHEAD study was initially funded by the European Commission, with Grant Number: FP7-HEALTH-2011-282562. Sciensano, the employer of CS and MA, received funding for the analysis of the Belgian part of the HPV-AHEAD study, in part, by a research grant from the Investigator Initiated Studies Program of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. MA was also supported by the Horizon 2020 Framework Programme for Research and Innovation of the European Commission, through the RISCC Network (Grant No. 847845); and the Belgian Foundation Against Cancer through the IHUVACC project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

CS, MA and JB designed the Belgian part of the HPV-AHEAD study; CS and MA performed the statistical analysis and interpreted the findings; CS also compiled the database, managed the Belgian part of the project and wrote the manuscript. IG collected all patient samples and the corresponding clinical information; PV, ML and OMV facilitated and supervised the specimen and clinical data collection. TG, DH, SR, AC, DA, and PB performed the respective DNA, RNA or p16 tests, and interpreted the data; they were supervised by MT, MP, RR, and MRP. RVK, NG, FM, BMLR, and JB were responsible for the histological review of all specimens. EL managed the overall HPV-AHEAD database, and validated the data entry. MT, RS, MP, MA, JB, SC, and RR were the PI’s of the HPV-AHEAD study and therefore responsible for the largest funding acquisition. TG, RR, IG, EL, FM, SC, JB, MT, and MA reviewed and/or edited the manuscript. All co-authors approved the final manuscript and its submission to this journal.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethical Committees of ‘GZA hospitals’ (ref nb: BVDE/hp/2013/01.147), ‘UZA & UA (University of Antwerp)’ (ref nb: 11/47/362) and IARC, Lyon, France (ref nb: 11–30). Informed consent of the individual patient was not necessary, as it concerns biobank-based research. The ethical principles, detailed by a European network specialized in biobanking (Hansson MG, Methods Mol.Biol 2011; 675:39–59), are respected. The need of informed consent was waived by the Ethical Committees of ‘GZA hospitals’ and ‘UZA & UA (University of Antwerp)’ for the Belgian patients.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

RR and SR are employees of Roche. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

hrHPV DNA PCR versus p16INK4a and combined hrHPV DNA/p16INK4a versus p16INK4a and hrHPV DNA PCR, for RNA positive and negative oropharyngeal cancers.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Simoens, C., Gheit, T., Ridder, R. et al. Accuracy of high-risk HPV DNA PCR, p16(INK4a) immunohistochemistry or the combination of both to diagnose HPV-driven oropharyngeal cancer. BMC Infect Dis 22, 676 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-022-07654-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-022-07654-2