Abstract

Background

Bronchiolitis is the most common viral infection of the lower respiratory tract in infants under 2 years of age. The aim of this study was to analyze and compare the seasonal bronchiolitis peaks before and during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Methods

Descriptive, prospective, and observational study. Patients with severe bronchiolitis admitted to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) of a referral tertiary hospital between September 2010 and June 2021 were included. Demographic data were collected. Viral laboratory-confirmation was carried out. Each season was analyzed and compared. The daily average temperature was collected.

Results

1116 patients were recruited, 58.2% of them males. The median age was 49 days. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) was isolated in 782 cases (70.1%). In April 2021, the first and only case of bronchiolitis caused by SARS-CoV-2 was identified. The pre- and post-pandemic periods were compared. There were statistically significant differences regarding: age, 47 vs. 73 days (p = 0.006), PICU and hospital length of stay (p = 0.024 and p = 0.001, respectively), and etiology (p = 0.031). The peak for bronchiolitis in 2020 was non-existent before week 52. A delayed peak was seen around week 26/2021. The mean temperature during the epidemic peak was 10ºC for the years of the last decade and is 23ºC for the present season.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic outbreak has led to a clearly observable epidemiological change regarding acute bronchiolitis, which should be studied in detail. The influence of the environmental temperature does not seem to determine the viral circulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Acute bronchiolitis is the most common viral infection of the lower respiratory tract in infants [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Although most children do not require hospitalization, approximately 3% of them are admitted to the hospital, accounting for 18% of total hospital admissions in children under 1 year of age [8,9,10]. Between 2 and 6% of the hospitalized patients require intensive care for respiratory support, which represents 13% of total PICU admissions, leading to high occupancy during the winter season [9, 11,12,13].

The seasonal pattern of bronchiolitis can be mainly explained by meteorological factors and the fact that transmission is facilitated by being indoors and in close quarters with others [14, 15]. RSV is by far the main causative viral etiological agent, although many others can cause this condition [13]. These viruses are usually spread by large droplets expelled from airways (which requires close contact) and transmission may also occur through fomites in the immediate environment of the infected person [16].

The COVID-19 outbreak, which started in early December 2019 in Wuhan, was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) on March 11th, 2020 [17]. The causative agent, the virus SARS-CoV-2, is believed to be mainly transmitted through the air, carried on droplets (requiring close contact for transmission) and aerosols. For this reason, social distancing, strict hand hygiene, and wearing masks are non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) that became mandatory worldwide [14, 15]. Moreover, school closures were widespread and many countries around the globe went on complete lockdown [14]. All of these actions may have influenced the transmission of other respiratory viruses [18].

A recent meta-analysis [19] looked at the prevalence of respiratory viruses in children with bronchiolitis in the pre-COVID-19 pandemic era, with RSV being the main cause of bronchiolitis in children, followed by rhinovirus (RV) and bocavirus (BoV). Global surveillance data suggest that the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic is a unique opportunity to obtain insight into the dynamics of various other infectious diseases in childhood, including bronchiolitis [20].

There is scarce data about the impact of SARS-CoV-2 regarding acute severe bronchiolitis, with little information available either on bronchiolitis caused by SARS-CoV-2 or on other bronchiolitis viral etiologies being crowded out.

The aim of this study was to describe and compare the bronchiolitis peak in a PICU, through different seasons, before and during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Methods

Epidemiological, clinical, and microbiological data were prospectively collected in a database created in 2010. Infants with severe bronchiolitis admitted to the PICU of a tertiary referral hospital (Sant Joan de Déu Hospital, Barcelona) from September 2010 to June 2021 were included. This study was approved by the institutional Clinical Research Ethics Committee and was performed in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

The following variables were included: age, sex, medical history, and previous comorbidities. Risk scores at admission and assessed severity of the bronchiolitis determined using the Bronchiolitis Score of Sant Joan de Déu (BROSJOD) [21] and the Pediatric Risk of Mortality Score III scale (PRISM III) [22]. The support required in the PICU, meaning the need for respiratory support, such as non-invasive ventilation (NIV) (excluding high flow oxygen therapy), and conventional mechanical ventilation (CMV), and for inotropic support. The length of stay (LOS) in the PICU and overall in the hospital. Mortality was recorded as any death occurring during the 28 days following PICU admission.

Determining the causal viral agent for the bronchiolitis was carried out using nasopharyngeal aspirate or a tracheal aspirate/bronchoalveolar lavage (in intubated patients) with a multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay (FilmArray®). The SARS-CoV-2 determination was carried out using nasopharyngeal swap/aspirate by real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) in each patient with respiratory symptomatology, since the beginning of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

The different seasons were analyzed and compared. Each season was determined to span from the beginning of September to the end of June of each year. The peak of each season was defined on week 52, in accordance with other published literature [23]. The daily average temperature was collected from the El Prat airport meteorological station, near Hospital Sant Joan de Déu and its demographic reference area. The mean monthly temperature of each season was analyzed. This data was obtained from the Surveillance Network and Air Pollution Forecast from the Government of Catalonia (La Generalitat).

Our research group, together with other regional Catalan hospitals, contributes to collecting data from patients with bronchiolitis admitted to each hospital, for the epidemiological surveillance network of Catalonia. In this way, data from all pediatric patients with acute severe bronchiolitis attributed to RSV who were admitted to the PICUs of Catalonia and Europe can be compared.

The aim of this study was to describe and compare the bronchiolitis peak in a PICU, through different seasons, before and during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Secondary objectives were to analyze the demographic characteristics, outcomes and temperature relationships.

The statistical analysis was executed using SPSS® 25.0 software. Categorical variables were expressed as absolute and relative rates, while continuous variables were expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR). The comparison of categorical variables was performed using the χ2-test and continuous variables were compared using the Mann–Whitney U-test. The significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

A total of 1116 patients with severe bronchiolitis were included, 58.2% (650 patients) of them being males. The median age at admission was 49 days (IQR 26–100). No previous comorbidities were described in 777 patients (69.6%). The median BROSJOD severity scale score was 9 points (IQR 7–11) and the median score on the PRISM III scale was 0 points (IQR 0–3). Most patients required intensive respiratory assistance: 1054 patients needed NIV (94.4%), while fewer patients required CMV (381 cases, 34.1%). Of the total, 143 patients needed inotropic support (12.8%). The median PICU LOS was 6 days (IQR 4–11) and the median hospital LOS was 12 days (IQR 8–19). Mortality occurred in 13 (1.2%) patients.

Regarding the viral etiology, 782 cases (70.1%) were due to RSV, followed by RV in 265 (23.7%) patients. There were 49 cases (4.4%) caused by seasonal coronaviruses other than SARS-CoV-2. The analysis of the viral incidence for each year is shown in Fig. 1.

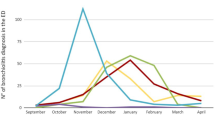

The total yearly number of bronchiolitis patients admitted to the PICU each season is shown in Fig. 2. The incidence curve for each season is shown in Fig. 3. Figure 4 illustrates the comparison between the median of the incidence curve from 2010 to 2020 and the incidence curve for 2021.

Lockdown in Catalonia was established from 14th of March to 2nd of May of 2020; followed by periods of opening/closing of restaurants, bars and social activities, depending on the SARS-CoV-2 rates. The use of mask has been mandatory until the present.

The pre- and post-pandemic periods were compared. There were statistically significant differences regarding the following variables: age, 47 days (IQR 26–97) vs. 73 (IQR 33–163), p = 0.006; PICU LOS, 6 days (IQR 4–11) vs. 5 (IQR 3–9), p = 0.024; hospital LOS, 12 days (IQR 8–19) vs. 10 days (IQR 7–13), p = 0.001; and etiology, p = 0.031. All the results compared the pre- and post-pandemic period, respectively. The data stemming from additional demographical, clinical and microbiological data are shown in Table 1.

When dividing the total annual number of bronchiolitis cases into those occurring before the peak and those occurring after the peak, which is established at week 52, a sharp decrease in cases was seen for this last season. These results are shown in Table 2. The 2020 bronchiolitis peak is thus non-existent before week 52.

The average monthly temperature of each season was analyzed. The mean temperature during the peak for the last decade was 10ºC. The mean temperature during the peak for this last season was 23 ºC. Details for the mean temperatures are included in Fig. 3.

Data on all pediatric patients with acute severe RSV-related bronchiolitis admitted to the PICUs of Catalonia and Europe were consulted and compared (Additional file 1). The incidence and the peak of RSV-attributed bronchiolitis, both for the previous decade and for the last season, are in line with our results. Details on this are shown in Additional file 2.

Discussion

This study has conclusively shown the very low burden of severe bronchiolitis during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and the delayed peak compared with other years in the last decade. Bronchiolitis has always been thought to be related with low temperatures and other meteorological conditions. Also, that throw children begin both RSV and influenza virus epidemics. However, this season breaks all the previously established rules. Due to the distribution of cases seen during this last season, the need has emerged for pediatricians to reconsider those previous theories.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of common respiratory viruses in children younger than 2 years with bronchiolitis in the pre-COVID pandemic era has been published recently [19]. It included 50 articles published between October 1999 and December 2017. RSV was largely the most commonly detected virus (59.2%), both as the only virus involved and in co-infections. In our study, upon analyzing the last ten years before SARS-CoV-2, the same results were found, with RSV being the most prevalent virus in patients with bronchiolitis (70.1%) [19].

As for bronchiolitis due to SARS-CoV-2, coronaviruses other than SARS-CoV-2 are also sometimes detected in respiratory samples, often presenting as co-infections. However, in contrast to what was reported by Milani PG et al [24], we did not find any cases of bronchiolitis due to SARS-CoV-2 during the 2019–2020 season. Instead, we identified the first case of SARS-CoV-2-related bronchiolitis in the 15th week of the current season (2020–2021). No other viruses were isolated for that patient. Recently, a multicenter study of children hospitalized with SARS-CoV-2 [25], concludes that SARS-CoV-2 infection does not seem to be a main trigger of severe bronchiolitis, and that children with this condition should be managed following the clinical practice guidelines.

In general, it has been described that children are less likely to become severely ill from SARS-CoV-2, especially when it comes to respiratory involvement. In Switzerland, one case of life-threatening bronchiolitis was diagnosed [26]. Two other cases were reported in France [27], both presenting with poorly tolerated high fever and neurological symptoms, and they developed acute bronchiolitis within 2 to 8 days. None of them required mechanical respiratory support other than supplemental oxygen.

Few cases of SARS-CoV-2 bronchiolitis or children with severe respiratory symptoms have been described. However, a recent cross-sectional seroprevalence concluded that children appear to have similar probability as adults to become infected by SARS-CoV-2 in quarantined family households, although they remain largely asymptomatic once infected [28].

Last year, some authors analyzed the prevalence of hospitalizations for respiratory diseases in childhood in recent years, with the aim of assessing the impact of social isolation due to COVID-19 on the seasonal behavior of respiratory tract diseases [29,30,31,32]. As seen in our results, Nascimento MS et al. [29] observed that the measures adopted during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic dramatically interfered with the seasonality of childhood respiratory diseases, reflected in the drastic 45% reduction in the number of hospitalizations and reduction in the length of hospital stay, both with statistically significant differences. What is even more remarkable is the finding that there was a reduction in bronchiolitis among the admitted patients from 7.3 to 0% during the social isolation period. Brisca et al. [33] also reported an overall drop in the total number of pediatric consultations in the emergency department of a tertiary Italian hospital, emphasizing a significant decrease in bronchiolitis cases, from 57 during 2019, to 21 during the 2020 lockdown (p < 0.01). Other recently published studies also confirm those findings and strongly suggest that the state of emergency, social distancing and other lockdown strategies are effective at slowing down the spread of respiratory diseases and decreasing the need for hospitalization among children [34,35,36,37,38,39]. All these results may influence future decision-making aiming to modulate the epidemiology of pediatric diseases.

In Belgium, some authors reported that stay-at-home orders, social distancing, face masks, and other NPIs not only impacted COVID-19, but also the dynamics of various other infectious diseases, having a high impact on seasonal bronchiolitis admissions in pediatric departments worldwide [23]. As is the case with our results, they found an over 99% reduction in the number of recorded RSV cases. However, even though the winter bronchiolitis peak was virtually nonexistent, they feared a delayed spring/summer bronchiolitis peak when most NPIs were relaxed and pre-pandemic life resumed. This became a reality, as shown in the results of our study, in the results from the Catalan region (Additional file 1), and in some other European countries [40] (Additional file 2).

On the other hand, it is interesting to point out, that bronchiolitis decline was mainly due to RSV. Instead, RV had been circulating with relative ease during the lockdown. Although a large decrease in the incidence of bronchiolitis due to RV has been observed, this decrease has been smaller than for RSV despite all isolation measures.

SARS-CoV-2 began to spread throughout the world at a time when the RSV and influenza season was expected to begin in the southern hemisphere. Afterwards, during their summer season, some countries in that hemisphere saw a rising incidence of bronchiolitis, mostly due to RSV, coinciding with the relaxation of social distancing measures. Nascimento et al [29] described an unexpected reduction in the number of hospitalizations in the pediatric population during the usual bronchiolitis season, which they attributed to the social isolation measures adopted. They worried about how 2021 would be. As seen in our results, bronchiolitis reappeared even though the meteorological conditions completely differ from the previous seasons. During this past season we saw a delayed peak of bronchiolitis, which appeared to be related with the withdrawal of social distancing measures.

The authors suggest that hypotheses to explain this late bronchiolitis peak could involve the reduction of isolation measures and the viral interference due to the global spread of a new virus during the same epidemiological period. It is expected that bronchiolitis will continue to be the annual epidemic disease among children under 2 years of age, filling up hospital beds and entailing a global health challenge. Further studies are needed to resolve these questions.

The main limitation of this study is its single-center design. However, a large sample of subjects was included, which permitted the comparison of homogeneous populations. A multi-center study could provide a wider view of the evolution of bronchiolitis during the last year and help explain how a classic childhood epidemic disease virtually disappeared in the context of the SARS-CoV2 outbreak and reappeared afterwards in completely different environmental conditions. The results obtained pointed towards the relevance of the isolation measures in decreasing respiratory viral infections among the pediatric population.

Conclusion

To sum up, a clear epidemiological change has been observed due to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. These changes should be studied in detail. The influence of the environmental temperature does not seem to have induced the viral distribution seen this last year, related to severe bronchiolitis, and thus other factors beyond temperature should be investigated. New studies should be considered to delve deeper into this analysis.

Availability of data and materials

Requests for data should be made to the corresponding author. Each request requires a research proposal including a clear research question and proposed analysis plan. Requests will be considered on an individual basis and are subject to review and approval by management committee human research ethics committees.

Abbreviations

- BoV:

-

Bocavirus

- BROSJOD:

-

Bronchiolitis Score of Sant Joan de Déu

- CMV:

-

Conventional mechanical ventilationÿ

- LOS:

-

Length of stay

- NIV:

-

Non-invasive ventilation

- NPIs:

-

Non-pharmaceutical interventions

- PICU:

-

Pediatric intensive care unit

- PRISM III:

-

Pediatric Risk of Mortality Score III scale

- RSV:

-

Respiratory syncytial virus

- RV:

-

Rhinovirus

References

Ralston SL, Lieberthal AS, Meissner HC, Alverson BK, Baley JE, Gadomski AM, et al. Clinical practice guideline: The diagnosis, management, and prevention of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2014;134(5):e1474–502. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-2742.

Maraga NF. Bronchiolitis: practice essentials, background, pathophysiology. Emedicine.medscape.com. 2018. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/961963-overview.

Lin JA, Madikians A. From bronchiolitis guideline to practice: A critical care perspective. World J Crit Care Med. 2015;4(3):152. https://doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v4.i3.152.

Lieberthal AS, Bauchner H, Hall CB, Johnson DW, Kotagal U, Light MJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4):1774–93. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-2223.

Guitart C, Alejandre C, Balaguer M, Esteban E, Cambra FJ, Jordan I. Impacto de una modificación de la guía de práctica clínica de la Academia Americana de Pediatría en el manejo de la bronquiolitis aguda grave en una unidad de cuidados intensivos pediátricos [The impact of modifying the American Academy of Pediatrics clinical practice guidelines as regards the management of severe acute bronchiolitis in a pediatric intensive care unit]. Med Intensiva. 2021;45:289–97.

Meissner HC. Viral bronchiolitis in children. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:62–72. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1413456.

Chkhaidze I, Zirakishvili D. Acute viral bronchiolitis in infants (Review). Georgian MedNews. 2017;264(264):43–50.

García GL, Korta MJ, Callejón CA. Bronquiolitis aguda viral Acute Viral Bronchiolitis. 2017;1:85–102.

Ghazaly M, Nadel S. Characteristics of children admitted to intensive care with acute bronchiolitis. Care. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-018-3138-6.

Hasegawa K, Tsugawa Y, Brown DFM, Mansbach JM, Camargo CA. Trends in bronchiolitis hospitalizations in the United States, 2000–2009. Pediatrics. 2013;132(1):28–36. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-3877.

Hall CB, Weinberg GA, Iwane MK, Blumkin AK, Edwards KM, Staat MA, et al. The Burden of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection in Young Children. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(6):588–98. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0804877.

Hasegawa K, Pate BM, Mansbach JM, Macias CG, Fisher ES, Piedra PA, et al. Risk factors for requiring intensive care among children admitted to ward with bronchiolitis. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15(1):77.

Mansbach JM, Piedra PA, Stevenson MD, Sullivan AF, Forgey TF, Clark S, et al. Prospective multicenter study of children with bronchiolitis requiring mechanical ventilation. Pediatrics. 2012;130:3. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-0444.

Susana RM. Bronchiolitis in the year of COVID-19. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2020;118(3):222–3.

Florin TA, Plint AC, Zorc JJ. Viral bronchiolitis. Lancet (London, England). 2017;389(10065):211–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30951-5.

Floret D. Prévention de la bronchiolite. Mesures à prendre dans les familles? Au cabinet? Dans les services hospitaliers? Modes de garde à proposer aux enfants [Prevention of bronchiolitis Measures to take in families? In the office? In hospital services? Safety modes to propose to children]. Arch Pediatr. 2001;8:70S-76S. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0929-693x(01)80159-7.

WHO. Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) situation report 5. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200125-sitrep-5-2019-ncov.pdf?sfvrsn=429b143d_8.

Fricke LM, Glöckner S, Dreier M, Lange B. Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions targeted at COVID-19 pandemic on influenza burden - a systematic review. J Infect. 2021;82(1):1–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2020.11.039.

Kenmoe S, Kengne-Nde C, Ebogo-Belobo JT, Mbaga DS, Fatawou Modiyinji A, Njouom R. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of common respiratory viruses in children < 2 years with bronchiolitis in the pre-COVID-19 pandemic era. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(11): e0242302. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0242302.

Boone SA, Gerba CP. Significance of fomites in the spread of respiratory and enteric viral disease. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(6):1687–96. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02051-06.

Balaguer M, Alejandre C, Vila D, Esteban E, Carrasco JL, Cambra FJ, et al. Bronchiolitis Score of Sant Joan de Déu: BROSJOD Score, validation and usefulness. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2017;52(4):533–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.23546.

Pollack MM, Patel KM, Ruttimann UE. PRISM III: an updated Pediatric Risk of Mortality score. Crit Care Med. 1996;24(5):743–52. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003246-199605000-00004.

Van Brusselen D, De Troeyer K, Ter Haar E, Vander Auwera A, Poschet K, Van Nuijs S, et al. Bronchiolitis in COVID-19 times: a nearly absent disease? Eur J Pediatr. 2021;30:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-021-03968-6.

Milani GP, Bollati V, Ruggiero L, Bosis S, Pinzani RM, Lunghi G, et al. Bronchiolitis and SARS-CoV-2. Arch Dis Child. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2020-321108.

Andina-Martinez D, Alonso-Cadenas JA, Cobos-Carrascosa E, et al. SARS-CoV-2 acute bronchiolitis in hospitalized children: neither frequent nor more severe. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.25731.

André MC, Pätzug K, Bielicki J, Gualco G, Busi I, Hammer J. Can SARS-CoV-2 cause life-threatening bronchiolitis in infants? Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020;55(11):2842–3. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.25030.

Grimaud E, Challiol M, Guilbaud C, Delestrain C, Madhi F, Ngo J, et al. Delayed acute bronchiolitis in infants hospitalized for COVID-19. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020;55(9):2211–2. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.24946.

Brotons P, Launes C, Buetas E, Fumado V, Henares D, de Sevilla MF, et al. Susceptibility to Sars-COV-2 Infection Among Children And Adults: A Seroprevalence Study of Family Households in the Barcelona Metropolitan Region. Spain Clin Infect Dis. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1721.

Nascimento MS, Baggio DM, Fascina LP, Prado C. Impact of social isolation due to COVID-19 on the seasonality of pediatric respiratory diseases. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(12). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0243694.

Goldman RD, Grafstein E, Barclay N, Irvine MA, Portales-Casamar E. Paediatric patients seen in 18 emergency departments during the COVID-19 pandemic. Emerg Med J. 2020;37(12):773–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2020-210273.

Valitutti F, Zenzeri L, Mauro A, Pacifico R, Borrelli M, Muzzica S, et al. Effect of population lockdown on pediatric emergency room demands in the era of COVID-19. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:521. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2020.00521.

Soo RJJ, Chiew CJ, Ma S, Pung R, Lee V. Decreased Influenza Incidence under COVID-19 Control Measures. Singapore Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(8):1933–5. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2608.201229.

Brisca G, Vagelli G, Tagliarini G, Rotulo A, Pirlo D, Romanengo M, et al. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on children with medical complexity in pediatric emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;42:225–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2020.11.066.

Kuitunen I, Artama M, Mäkelä L, Backman K, Heiskanen-Kosma T, Renko M. Effect of Social Distancing Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Incidence of Viral Respiratory Tract Infections in Children in Finland During Early 2020. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39(12):e423–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0000000000002845.

Hatoun J, Correa ET, Donahue SMA, Vernacchio L. Social Distancing for COVID-19 and diagnoses of other infectious diseases in children. Pediatrics. 2020;146(4): e2020006460. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-006460.

Rotulo GA, Percivale B, Molteni M, Naim A, Brisca G, Piccotti E, et al. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on infectious diseases epidemiology: The experience of a tertiary Italian Pediatric Emergency Department. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;43:115–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2021.01.065.

Yeoh DK, Foley DA, Minney-Smith CA, Martin AC, Mace AO, Sikazwe CT, et al. The impact of COVID-19 public health measures on detections of influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in children during the Australian winter. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1475.

Angoulvant F, Ouldali N, Yang DD, Filser M, Gajdos V, Rybak A et al. COVID-19 pandemic: impact caused by school closure and national lockdown on pediatric visits and admissions for viral and non-viral infections, a time series analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2020: doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa710.

Friedrich F, Ongaratto R, Scotta MC, Veras TN, Stein R, Lumertz MS, et al. Early impact of social distancing in response to COVID-19 on hospitalizations for acute bronchiolitis in infants in Brazil. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(12):2071–5.

Surveillance Atlas of Infectious Diseases. http://atlas.ecdc.europa.eu/public/index.aspx

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank children and families who agreed being a part of the study. Authors of hospital Network for RSV surveillance in Catalonia: Andrés Antón Pagarolas, Jorgina Vila, Ermengol Coma, Iolanda Jordan, Valentí Pineda, Ester Castellarnau, Mª José Centelles-Serrano, Nuria López, Ingrid Badia Vilaró.

Funding

No funded was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

MB and IJ conceptualized and designed the study, drafted the initial manuscript, coordinated and supervised data collection, and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. CG, SBP, CA, GA conceptualized and designed the study, designed the data collection instruments, collected data, carried out the analyses, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. CL and Dr. FJC coordinated and supervised data collection and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. The Hospital Network for RSV surveillance in Catalonia facilitated all collected data from all pediatric patients with acute severe bronchiolitis attributed to RSV who were admitted to the PICUs of Catalonia. All the authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was prospectively approved by the local Healthcare Ethics Committee and the Institutional Review Board (CEIm Fundación Sant Joan de Déu, Barcelona, Spain). Informed consent to participate was provided prospectively from parents and/or legal guardian. All methods were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

No applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Data of the acute severe RSV-related bronchiolitis admitted to the PICUs in Catalonia and Europe.

Additional file 2.

The incidence and the peak of RSV-attributed bronchiolitis: Temporal comparison.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Guitart, C., Bobillo-Perez, S., Alejandre, C. et al. Bronchiolitis, epidemiological changes during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. BMC Infect Dis 22, 84 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-022-07041-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-022-07041-x