Abstract

Background

The probability of hospitalization in patients suffering from community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) with an underlying comorbidity, such as a cardiac pathology, is 73-fold higher than that in CAP patients without a comorbidity. Although previous studies have investigated patients with cardiac events and pneumonia, they have not studied the burden of disease in depth at the population level. The objective of this study is to provide population-level data on patients ≥60 years old who were hospitalized with pneumonia with comorbid cardiovascular disease (CVD) in Spain over a period of 19 years (1997–2015).

Methods

This is a retrospective study based on a minimum basic data set (MBDS). The following variables were collected: age, sex, re-admission (yes/no), hospital stay (days), and other diagnoses. Hospitalization rate (per 100,000 inhabitants), mortality rate (per 100,000 inhabitants), and lethality rate (%) were obtained, and the 95% confidence interval of each rate was calculated. Analyses were stratified by age (categorized into 4-year intervals), sex, and year of admission. Differences were assessed for significance with the chi-squared test for proportions and the Poisson model for rates. Logistic regression was run with in-hospital survival as the dependent variable and sex, age, year of admission, and re-admission (yes/no) as the independent variables. The level of significance was p < 0.005.

Results

The total number of patients ≥60 years old hospitalized for pneumonia with comorbid CVD was 99,346. The rates of hospitalization, mortality, and lethality increased significantly with age over the 19 years. Men had higher rates of hospitalization and mortality. The probability of a patient with CAP and CVD dying was correlated with male sex, older age, hospital re-admission, and having been hospitalized earlier in the study period.

Conclusions

Community-acquired pneumonia with comorbid cardiovascular disease continues to be a major cause of hospitalization in Spain, especially in the elderly population, making it necessary to develop more preventive strategies for this group of patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Lower respiratory tract diseases are the fourth leading cause of death in the world [1]. Pneumococcal pneumonias accounted for more than 20% of lower respiratory-related diseases in 2013 [2] and represented the third-leading cause of years of life lost adjusted for disability [3]. This problem is particularly pertinent in people ≥65 years of age [4], for whom there is also a higher health expenditure when treating community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) [5]. The probability of hospitalization in patients suffering from CAP with an underlying comorbidity in the form of a cardiac, respiratory, or metabolic pathology is 73-fold higher than that in CAP patients without a comorbidity [6].

The main causes of mortality worldwide are ischaemic cardiomyopathy and stroke [7]. In Spain, diseases of the circulatory system were the main cause of death in 2016 [8]. Cardiac events in patients with CAP are significantly associated with in-hospital mortality [9], a longer hospital stay, and more severe CAP [10]. Furthermore, CAP can exacerbate or cause cardiovascular complications [11], and cardiac markers are predictors of mortality in patients hospitalized for CAP [12]. In addition to CAP in general, pneumococcal pneumonia confers an increased risk of having a cardiac event [13]. Furthermore, cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a risk factor for CAP [14, 15].

Population databases are useful for establishing disease burden because they have a complete and standardized collection of hospitalization records. The Spanish National Discharge Database has proven to be a reliable tool for studying the hospitalization load for CAP [16, 17].

Previous studies have investigated patients with cardiac events and pneumonia, but the burden of disease at the population level has not been studied in depth [18]. The objective of this study is to provide population data on the hospitalization burden of CAP with comorbid CVD in Spain over a period of 19 years (1997–2015).

Methods

This is a retrospective study based on a minimum basic data set (MBDS) and supported by the Ministry of Health of Spain. This system used the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9-CM) and covered approximately 98% of public hospitals and some private hospitals. The public health care system covers 99.5% of the Spanish population, making it a representation of people hospitalized at the state level. The MBDS has been validated with regard to data quality and overall methodology by the Ministry of Health of Spain [19, 20].

All hospital admissions of patients aged 60 years and older for all causes, with pneumonia (ICD-9-CM 480–486) in the principal diagnostics position at admission and at least one diagnosis of cardiovascular disease, occurring between 1st January 1997 and 31st December 2015 in Spain were obtained from the MBDS. The eligible CVDs are listed in Table 1 and were based on their use by other authors [21].

The following variables were collected: age, sex, re-admission (yes/no), hospital stay (days), other diagnoses (up to 13 additional diagnostic positions) and outcome (discharge/death). Re-admission was defined as “being re-admitted to the hospital with the same principal diagnostic code at admission within 30 days of being discharged.” Absolute (n) and relative (%) frequencies were calculated for the number of hospitalizations per year, sex, re-admission, and death. The mean and standard deviation (SD) of age, hospital stay, and number of diagnoses were calculated. The rate of hospitalization (per 100,000 inhabitants), in-hospital mortality rate (per 100,000 inhabitants), and in-hospital lethality rate (% of hospitalizations) were calculated, and corrected population data from the municipal records, extracted from the National Institute of Statistics (https://ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/en/categoria.htm?c=Estadistica_P&cid=1254734710984, accessed on 28 April 2020), were used as the denominator for the hospitalization and mortality rates. The 95% CI of each rate was calculated. The results were stratified by sex, age (categorized into 4-year intervals), and year of admission. Significant differences were analysed with the chi-squared test for proportions and the Poisson model for rates during the period studied. Logistic regression was performed with in-hospital survival as the dependent variable and sex, age, year, and re-admission as independent variables. The level of significance was p < 0.05.

For the statistical analysis, we used SPSS v.22 software (IBM Corp., New York, USA).

The personal information of each subject was delivered to the researchers anonymously, impeding the traceability of the subject, in strict adherence to Spanish and European legislation. The present project received a waiver from the local ethics committee, Comité de Ética de la Investigación de la Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, which ruled that no formal ethics approval was required.

Results

The total number of patients ≥60 years old with CVD who were hospitalized for pneumonia was 99,346 in the study period. A total of 60.7% were male, and the average age was 79.80 years (SD: 8.26), which was distributed as follows: 60–64 years, 4.5%; 65–69 years, 7.9%; 70–74 years, 13.7%; 75–79 years, 20%; 80–84 years, 22.9%; and ≥ 85 years, 30.9%. The average length of hospital stay was 11.23 days (SD: 10.5), and 12.6% were re-admitted 30 days after discharge. Overall, 13.8% of patients died, reaching 17.7% of patients when counting re-admissions. A total of 75.7% of patients had pneumococcal pneumonia (ICD-9 CM: code 481) in the principal diagnostic position. The mean number of diagnoses present was 8.47 (3.03) per patient.

The annual global hospitalization rate due to CAP with comorbid CVD was 55.27 (95% CI: 54.92–55.61) hospitalizations per 100,000 inhabitants, reaching 30,739 hospitalizations in the age group of ≥85 years. The annual global in-hospital mortality rate was 32.71 (95% CI: 32.16–33.26) deaths per 100,000 inhabitants, reaching 656.50 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants in those over 85 years. The global annual in-hospital lethality rate was 13.81% (95% CI: 13.60–14.02), with the highest rate at 19.53% in the age group older than 85 years.

Table 2 shows the rates of hospitalization and mortality per 100,000 inhabitants and the lethality rate (%) by age and sex. Rates increase significantly with age. The mortality and hospitalization rates were significantly higher in men in all age groups (p < 0.001), although the lethality rate showed no sex differences.

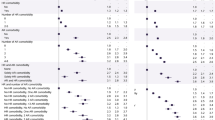

Figure 1 shows the time trend of incident hospitalizations due to CAP and its associated mortality rates stratified by sex. Using a linear approximation in Poisson rate regression, the declining trend in hospitalizations was similar for men and women (men: -2.3% (RR 0.98, 0.975–0.978) and women − 2.2% (RR = 0.98, 0.976–0.980) per year). A similar trend was observed for the mortality rate. Using a linear approximation in Poisson rate regression, the declining trend in mortality was 4% for men (RR 0.96, 0.956–0.964) and 3.4% for women (RR = 0.97, 0.961–0.970) per year.

Figure 2 shows the hospitalization rate according to age group over the 19-year study period. An increase was seen in all age groups between 2007 and 2010, then a decrease until 2014, followed by an increase again in 2015. Using a linear approximation in Poisson rate regression, the declining trend in hospitalizations was significantly modified by age group (pINT < 0.001), with lower reductions in hospitalizations by year as age increased, ranging from a − 3.5% reduction in the youngest age group [60,65) to a − 1.3% reduction in the oldest age group [85+).

Death during hospitalization was significantly associated with age in years (OR = 1.05, 95% CI: 1.41–2.19) and readmission to the hospital within 30 days (OR = 1.70, 95% CI: 1.62–1.79); moreover, it was inversely associated with being female (OR = 0.94, 95% CI: 0.90–0.98) and the year of hospitalization (OR = 0.97, 95% CI: 0.97–0.98).

Discussion

This study evaluated the burden of hospitalizations for pneumonia with CVD at the population level in patients older than 60 years in Spain and confirmed the high burden of the disease in this risk group. Each year, on average, 55 out of 100,000 inhabitants older than 60 years of age were hospitalized for CAP with a comorbid CVD diagnosis in Spain. Using a linear time trend, a 2% reduction in hospitalization rates could be observed, a tendency more pronounced in the younger age group of 60–65-year-olds.

In the period described, there were many hospitalizations for CAP with comorbid CVD in people over 60 years of age, and the group older than 85 made up almost a third of them. This is important because the population of Spain is ageing overall, and its life expectancy is increasing. Hospitalized older people also present with complications that negatively affect their health and later recovery [20], especially patients with risk factors such as CVD. The average hospital stay was 11 days, and the average length of stay is an independent risk factor for death [21], so CVD patients are especially sensitive to the complications of pneumonia.

Three-quarters of the pneumonia cases were pneumococcal pneumonia, which was in line with earlier data [22]. For CAP, diagnosis 481 is the most sensitive, regardless of the diagnostic position [23]. When analysing the rates by sex, higher rates were observed in men, in agreement with the literature that uses the same data source [24], and are probably related to aspects of lifestyle, since CVD is associated with unhealthy lifestyle habits such as smoking, which is more common in men in Spain [25]. In addition, the second-leading cause of death in men is CVD, and the mortality rate from pneumonia is higher in men [25].

When our population was stratified by age, age was a risk factor for hospitalization and in-hospital death. This is consistent with the report that the highest percentage of deaths from pneumonia and influenza occur in people older than 75 years in Spain [25].

Between 2007 and 2010, there was an increase in HR, probably related to the fact that these were the years under study in which Spain had the greatest economic inequality in the population related to the economic crisis [26]. Specifically, in 2009, peak hospitalization occurred at all ages, a fact that may also be related to pandemic influenza A (H1N1) [27]. This increase in HR by year has also been seen in other studies of CAP in patients hospitalized in Spain [28]. There was also a decrease in 2006, probably related to the fact that this year was the hottest in the period according to the annual climatological summary of the State Meteorological Agency (Spanish Government) [29]. Finally, there was a hint of an increase in 2015 that must be given considerable attention, which makes it clear that CAP with comorbid CVD is not a thing of the past and that we should continue monitoring and studying it to protect our vulnerable population in the final stages of life.

The risk of death during hospitalization was significantly increased for men, which was consistent with the increased rate of lethality in men in our study for every age group; increased with re-admission, related to hospital stay, specifically in people older than 60 years with CAP, reducing the quality of life [30] and therefore raising the probability of being re-admitted in worse baseline condition; and finally, increased with previous admission within this period of 19 years, which can probably be explained by the improvement of health systems in our environment during this period.

This study has some limitations derived from the use of the MBDS. Reliability depends on the quality of the discharge report and clinical history, as well as on the variables of the coding process. To mitigate this variability, quality controls have been performed to evaluate the MBDS validity, and the coding process has improved since 2001. A strength is that the MBDS allowed us to carry out a complete follow-up over time for the entire population of Spain and has been used by several authors [16, 28, 31]. Specific data about bacteriological confirmation are not available within the CMBD, but a previous study assessing the accuracy of ICD-9-CM for pneumococcal pneumonia has shown high sensitivity and specificity for code 481 [23]. The use of ICD9 codes for the diagnosis of CVD and pneumonia from administrative databases could also be a limitation regarding sensitivity and specificity. However, in general, discharge diagnosis codes have proven to have a high positive predictive value (PPV) for identifying hospitalizations for common, serious infections among middle-aged and older adults [32], particularly in a setting such as Spain, where the reimbursement of physicians is not linked to the disease being treated and its severity.

The epidemiology and the rates reflected in this study of patients hospitalized with CAP and comorbid CVD reflect the need to develop and evaluate preventive measures such as vaccination for CAP in risk groups along with other vaccines, such as that against influenza, to achieve an effect in patients who are most affected by CAP, older patients, and those with CVD.

In the immunization schedule for individuals of all ages, the Spanish Ministry of Health recommends vaccination against pneumococcal infection in older people, preferably maintaining the strategy agreed upon by the Interterritorial Council of the National Health System since 2004 consisting of systematic vaccination from 65 years of age with VNP23 and not recommending periodic booster doses except in certain risk situations. The same document also refers to the VNC13 conjugate vaccine and indicates it for risk groups in the adult population and acknowledges that some autonomous regions have other alternative strategies for use of the 13v conjugate vaccine. In this sense, Madrid in 2016, and La Rioja, Asturias, Castilla y León, Galicia and Andalusia decided to apply more extensive indications of this vaccine both according to age and/or the presence of associated chronic diseases, maintaining the sequential pattern of the 13v conjugate vaccine followed by the 23v polysaccharide vaccine for risk groups [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41].

Our results support the recommendation of experts in that an important potential to reduce CAP hospitalizations in patients with a concomitant CVD diagnosis still exists.

Conclusions

The rates of hospitalization, mortality, and lethality increased significantly with age during the 19 years of this survey. Men had higher hospitalization and mortality rates. In-hospital death in patients with CAP and CVD was correlated with male sex, older age, and re-admission.

Community-acquired pneumonia with comorbid cardiovascular disease continues to be a major cause of hospitalization in Spain, especially in the elderly population, making it necessary to develop more preventive strategies for this group of patients.

Availability of data and materials

Most of the data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its additional file], although restrictions apply to the availability of some data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available.

Abbreviations

- CAP:

-

Community-acquired pneumonia

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- HR:

-

Hospitalization rate

- MR:

-

Mortality rate

- LR:

-

Lethality rate

References

Niederman M, Luna C. Community-acquired pneumonia guidelines: a global perspective. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;33:298–310. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0032-1315642.

GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;385:117–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2.Global.

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. University of Washington. GBD Compare | IHME Viz Hub 2016. https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/. Accedido 28 de noviembre de 2017.

Feldman C. Pneumonia in the elderly. Clin Chest Med. 1999;20:563–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-5231(05)70236-7.

Niederman MS, McCombs JS, Unger AN, Kumar A, Popovian R. The cost of treating community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Ther. 1998;20:820–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2918(98)80144-6.

Gil-Prieto R, Pascual-Garcia R, Walter S, Álvaro-Meca A, Gil-De-Miguel Á. Risk of hospitalization due to pneumococcal disease in adults in Spain. The CORIENNE study. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;0:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2016.1143577.

OMS | Las 10 principales causas de defunción 2017. http://origin.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs310/es/. Accedido 18 de mayo de 2018.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Defunciones según causa de muerte. Madrid: Notas de prensa; 2017.

Cilli A, Cakin O, Aksoy E, Kargin F, Adiguzel N, Karakurt Z, et al. Acute cardiac events in severe community-acquired pneumonia: a multicenter study. Clin Respir J. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/crj.12791.

Eman Shebl R, Hamouda MS. Outcome of community-acquired pneumonia with cardiac complications. Egypt J Chest Dis Tuberc. 2015;64:633–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcdt.2015.03.009.

Restrepo MI, Reyes LF. Pneumonia as a cardiovascular disease. Respirology. 2018;23:250–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/resp.13233.

Vestjens SMT, Spoorenberg SMC, Rijkers GT, Grutters JC, Ten Berg JM, Noordzij PG, et al. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin T predicts mortality after hospitalization for community-acquired pneumonia. Respirology. 2017;22:1000–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/resp.12996.

Musher DM, Rueda AM, Kaka AS, Mapara SM. The association between pneumococcal pneumonia and acute cardiac events. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:158–65. https://doi.org/10.1086/518849.

Almirall J, Serra-Prat M, Bolíbar I, Balasso V. Risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia in adults: a systematic review of observational studies. Respiration. 2017;94:299–311. https://doi.org/10.1159/000479089.

Rivero-Calle I, Pardo-Seco J, Aldaz P, Vargas DA, Mascarós E, Redondo E, et al. Incidence and risk factor prevalence of community-acquired pneumonia in adults in primary care in Spain (NEUMO-ES-RISK project). BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-016-1974-4.

Gil A, San-Martín M, Carrasco PGA. Epidemiology of pneumonia hospitalisations in Spain 1995–1998. J Inf Secur. 2002;44:84–7.

Gil A, Gil R, Oyagüez I, Carrasco PGA. Hospitalisation by pneumonia and influenza in the 50–64 year old population in Spain (1999–2002). Hum Vaccines. 2006;2:181–4.

Klare B, Kubini R, Ewig S. Risk factors for pneumonia in patients with cardiovascular diseases. Pneumologie. 2002;56:781–8. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2002-36123.

Rodríguez del Águila M, Perea-Milla E, Librero J, Buzón Barrera M, Rivas Ruiz F. Análisis del control de calidad del Conjunto Mínimo de Datos Básicos de Andalucía en los años 2000 a 2003. Sevilla; 2004.

Instituto de Información Sanitaria. Metodología de análisis de la hospitalización en el sistema nacional de salud. Madrid: Modelo de indicadores basado en el registro de altas (CMBD) documento base; 2007.

Ernst JM. Who is at risk for influenza? Using criteria other than age. Manag Care. 2000;9:46 48–50, 52–5.

Rojano I, Luque X, Ferrin PS, Salvà A. Complicaciones de la hospitalización en personas mayores. Med Clin. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcli.2015.12.015.

Guevara RE, Butler JC, Marston BJ, Plouffe JF, File TM, Breiman RF. Accuracy of ICD-9-CM codes in detecting community-acquired pneumococcal pneumonia for incidence and vaccine efficacy studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:282–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009804.

Gil-prieto R, García-garcía L, Álvaro-meca A, Méndez C, García A, Gil de Miguel Á. The burden of hospitalisations for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) and pneumococcal pneumonia in adults in Spain (2003-2007). Vaccine. 2011;29:412–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.11.025.

Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Indicadores de Salud 2017. Evolución de los indicadores del estado de salud en España y su magnitud en el contexto de la Unión Europea. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad; 2017. https://www.mscbs.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/inforRecopilaciones/docs/Indicadores2017.pdf.

Panorama de la sociedad 2014: Indicadores sociales de la OCDE. La crisis y sus consecuencias/Organización de Cooperación y Desarrollo Económico. Madrid: Ministerio de Empleo y Seguridad Social de España. Subdirección General de Información Administrativa y Publicaciones; 2014. p. 152.

Centro Nacional de Epidemiología. Casos humanos de infección por nuevo virus de la gripe A (H1N1). Evolución de la situación en España. Boletín Epidemiológico Sem. 2009;17:1–4.

López-de-Andrés A, de Miguel-Díez J, Jiménez-Trujillo I, Hernández-Barrera V, de Miguel-Yanes JM, Méndez-Bailón M, et al. Hospitalisation with community-acquired pneumonia among patients with type 2 diabetes: an observational population-based study in Spain from 2004 to 2013. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e013097. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013097.

Annual Climatological summaries. Spanish Agency of meteorology. Madrid 2006. Available at URL: http://www.aemet.es/documentos/es/serviciosclimaticos/vigilancia_clima/resumenes_climat/anuales/res_anual_clim_2006.pdf.

Mangen MJJ, Huijts SM, Bonten MJM, de Wit GA. The impact of community-acquired pneumonia on the health-related quality-of-life in elderly. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17:208. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-017-2302-3.

Lorente Antoñanzas R, Varona Malumbres JL, Antoñanzas Villar F, Rejas-Gutierrez J. A dynamic model to estimate the budget impact of a pneumococcal vaccination program in a 65 year-old immunocompetent Spanish cohort with 13-Valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Rev Esp Salud Pública. 2016;90:1–12.

Wiese AD, Griffin MR, Stein CM, Schaffner W, Greevy RA, Mitchel EF Jr, Grijalva CG. Validation of discharge diagnosis codes to identify serious infections among middle age and older adults. BMJ Open. 2018;8(6):e020857. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020857.

Redondo E, Rivero-Calle I, Mascarós E, Díaz-Maroto JL, Linares M, Gil Á, et al. El nuevo calendario vacunal oficial del adulto no contempla la prevención de la neumonía neumocócica. Rev Esp Quim. 2019;32:281–3.

González-Romo F, Picazo J, García Rojas A, Labrador Horrillo M, Barrios V, Magro M, et al. Consenso sobre la vacunación anti-neumocócica en el adulto por riesgo de edad y patología de base. Actualización 2017. Rev Esp Quim. 2017;30:142–68.

Gobierno de la Rioja. Vacunación Frente a Enfermedad Neumocócica en Rioja. 2017. http://www.riojasalud.es/f/rs/docs/INFORMACION_NEUMOC%C3%93CICA_65A%C3%91 MARZO 2017.pdf.

Direccion General de Salud Pública. Programa de Vacunaciones. Actualizaciones en el programa de Vacunaciones de Asturias para el 2018. Available at http://www.codepa.es/modulgex/workspace/publico/modulos/web/docs/apartados/65/040918_023255_3181688223.pdf.

Conselleria de Sanidade. Xunta de Galicia. Vacinación Antipneumocócica En Adultos. 2017. Available at: https://www.sergas.es/Saudepublica/Documents/4536/Nota_informativa_vacinacion_antipneumococica_2017.pdf.

Comunidad de Madrid. Calendario de vacunación en el adulto año 2019. Available at: http://www.comunidad.madrid/sites/default/files/doc/sanidad/prev/calendario_de_vacunacion_del_adulto._ano_2019.pdf.

Boletín Oficial e Castilla y León. Viernes 14 de diciembre 2018. Número 241, página 49.230. http://bocyl.jcyl.es/boletines/2018/12/14/pdf/BOCYL-D-14122018-12.pdf.

Junta de Andalucia. Consejería de Salud y Familias. Actualidad. Disponible en https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/organismos/saludyfamilias/actualidad/noticias/detalle/207528.html. 2019.

Calendario de vacunación para todas las Edades de la Vida el Ministerio de Sanidad. Available at: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/prevPromocion/vacunaciones/docs/CalendarioVacunacion_Todalavida.pdf.

Acknowledgements

The results, discussion and conclusions of this study are those perceived by the authors only. The authors thank the Subdirección General del Instituto de Información Sanitaria for providing the information on which this study is based.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LAF, AGM, and RGP participated in the conception and design of the study. RGP participated in the acquisition of data. LAF and RGP analysed and interpreted the patient data. LAF was a major contributor to writing the manuscript. AGM and RGP supervised the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The information contained in the MBDS is completely anonymous and includes no data that could identify patients, doctors, or centres, ensuring full confidentiality. Raw data are freely accessible in the minimum basic data set (MBDS) supported by the Ministry of Health of Spain.

The present project received a waiver from the local ethics committee, Comité de Ética de la Investigación de la Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, which ruled that no formal ethics approval was required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

AGM and RGP have received research grants and/or honoraria as a consultant/advisor and/or speaker from Sanofi Pasteur MSD, Merck, Sanofi Pasteur, Pfizer and Novartis. None declared for the rest of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Arias-Fernández, L., Gil-Prieto, R. & Gil-de-Miguel, Á. Incidence, mortality, and lethality of hospitalizations for community-acquired pneumonia with comorbid cardiovascular disease in Spain (1997–2015). BMC Infect Dis 20, 477 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05208-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05208-y