Abstract

Background

Challenges accessing nearby health facilities may be a barrier to initiating and completing tuberculosis (TB) treatment. We aimed to evaluate whether distance from residence to health facility chosen for treatment is associated with TB treatment outcomes.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of all patients initiating TB treatment at six health facilities in Kampala from 2014 to 2016. We investigated associations between distance to treating facility and unfavorable TB treatment outcomes (death, loss to follow up, or treatment failure) using multivariable Poisson regression.

Results

Unfavorable treatment outcomes occurred in 20% (339/1691) of TB patients. The adjusted relative risk (aRR) for unfavorable treatment outcomes (compared to treatment success) was 0.87 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.70, 1.07) for patients living ≥2 km from the facility compared to those living closer. When we separately compared each type of unfavorable treatment outcome to favorable outcomes, those living ≥2 km from the facility had increased risk of death (aRR 1.42 [95%CI 0.99, 2.03]) but decreased risk for loss to follow-up (aRR 0.57 [95%CI 0.41, 0.78]) than those living within 2 km.

Conclusions

Distance from home residence to TB treatment facility is associated with increased risk of death but decreased risk of loss to follow up. Those who seek care further from home may have advanced disease, but once enrolled may be more likely to remain in treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Although tuberculosis (TB) is both preventable and treatable, it is the leading cause of death due to a single pathogen worldwide [1]. One challenge in TB control is maintaining adherence to a minimum of six months of treatment. The World Health Organization estimates that 82% of patients worldwide who start treatment for TB experience treatment success (defined as treatment completion or cure); this percentage has not improved substantively in the past decade [1]. People with restricted access to health care may not be able to initiate and complete TB treatment as recommended. Risk factors for unfavorable treatment outcomes include demographic, clinical, and health systems characteristics [2,3,4].

Geographic barriers to care, including physical distance to a health facility, may contribute to poor treatment outcomes. Distance from home to health facility has been associated with decreased access to a wide range of health services and outcomes, including poor HIV treatment clinic attendance [5] and antiretroviral adherence [6], lower likelihood of facility-based childbirth [7], and maternal [8] and child mortality [9]. Geographic barriers to care have been linked to delays [6, 10], loss-to follow up [11], and lack of adherence during the TB diagnostic evaluation and treatment processes [10]. Whether these associations translate into worse treatment outcomes remains uncertain. As the effect of geographic barriers has primarily been noted in rural areas where patients likely have limited options as to where they seek care and even the closest health care facilities may require more than an hour of travel, we aimed to understand the effect of these barriers on TB treatment outcomes in the context of a densely populated, urban setting where there are many TB treatment facilities available and patients may choose to seek care at facilities other than the ones closest to them.

Understanding links between geographic barriers to care and TB treatment outcomes may help identify a population at risk for unfavorable treatment outcomes that could be targeted with interventions to reduce barriers to care and improve outcomes. We therefore sought to characterize the association of distance from home to health facility and TB treatment outcomes in six public and private health facilities in Makindye division, Kampala district, Uganda.

Methods

Study overview and population

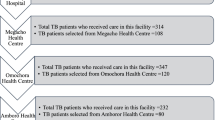

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of TB patients at one public (Kisugu Health Center, the primary public TB treatment facility in this area) and five private urban outpatient health facilities serving the population of Kisugu and Wabigalo parishes of Makindye division, Kampala, Uganda. Facilities were included if they provided TB care to an average of at least one patient per month from Kisugu or Wabigalo parish. At each of the selected facilities, all patients initiating TB treatment from January 1, 2014 to December 31, 2016 and who lived in Uganda were included. The National TB Control Program oversees all TB care and patients may seek treatment at any facility of their choosing. Treatment of adult TB is largely decentralized in Uganda; TB cases requiring hospitalization or advanced clinical care, such as pediatric TB or drug-resistant TB, may be diagnosed at these facilities in the community but are referred to referral hospitals for their treatment and management and would not be included in this analysis. All facilities providing TB treatment in Uganda are expected to follow the national guidelines for TB treatment, although variation in implementation may exist and additional services (such as laboratory tests) may incur additional charges at private facilities. In urban settings, the national guidelines recommend that patients or their treatment supporters report to the treating facility to receive their anti-TB drugs every two weeks during the intensive phase and every four weeks during the continuation phase.

Data collection

Demographic and clinical data were abstracted retrospectively from the Facility TB Registers, including treatment facility, parish of residence, age at diagnosis, sex, HIV status, site of disease (pulmonary vs. extrapulmonary), treatment regimen, diagnostic test results (sputum microscopy and Xpert MTB/RIF [Cepheid, Inc., Sunnyvale, California, USA]), date of treatment initiation, and treatment outcome. Data were abstracted directly as written in the registers with guidance from health facility staff as needed. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) [12, 13] hosted at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Measurement of primary exposure and outcome

We used reported area of residence to calculate two measures of distance from residence to the health facility where the patient chose to receive TB treatment. The TB registers do not capture patient addresses but do have information on the administrative area of residence, the smallest of which is the parish with a median size of 0.13 km2 and median population of 23,041 within Kampala. The centroid of the parish of residence was used to estimate each patient’s location of residence based on parish boundaries provided by Uganda Bureau of Statistics 2014 census data. We calculated Euclidean distance as a straight line from parish centroid to each health facility using ArcGIS (ESRI, Redlands, California, USA). Additionally, we used OpenStreetMap (OpenStreetMap Foundation, Cambridge, United Kingdom) to define road networks and calculated travel distance based on the shortest available route using the Network Analysis tool in ArcGIS.

Treatment outcomes following the World Health Organization (WHO) definitions were abstracted from the Facility TB Registers. “Unfavorable” outcomes included treatment failure, death, and loss to follow-up (including those with a documented outcome of default); patients with no documented outcome were not included in the analysis, although we performed a sensitivity analysis in which these patients were considered to have unfavorable outcomes. These were compared to “favorable” treatment outcomes of treatment completion or cure (also called treatment success). Patients with an outcome of “transferred out” (with no additional treatment outcome information from their receiving facility) were excluded.

Facility TB notification rate

We calculated an average annual “facility TB notification rate” for each parish, which we defined as the annual average number of cases from the parish reported at the six facilities divided by the parish’s 2014 population from the Uganda Bureau of Statistics [14]. We used Poisson regression to assess the association of Euclidean distance from the parish centroid to the facility where the patients received TB treatment on facility TB notification rates.

Distance to TB treatment facility and treatment outcomes

To measure the association between distance from residence to TB treatment facility and treatment outcome at the individual level, our primary exposure was Euclidean distance categorized into four categories: < 2 km, 2 to < 5 km, 5 to < 10 km, and ≥ 10 km. These categories were chosen based on the following rationale: < 2 km is walking distance and therefore distance should not represent significant barriers to care; 2 to < 5 km is still quite close but may require additional means of transport or additional travel time; 5 to < 10 km is within the urban area but may take significant time and/or resources to travel; ≥10 km represents a significant investment in time and resources to reach the facility. For additional analyses using shortest available route travel distance, we used the same four distance categories. We also considered a binary exposure with distance dichotomized as < 2 km or ≥ 2 km. Our outcome of interest was unfavorable treatment outcome, which was defined as above.

Patient characteristics were compared across the four exposure categories for Euclidean distance using chi-square tests. Risk factors of interest were defined a priori as characteristics known to be associated with TB treatment outcomes and that conceivably could lead to differences in care-seeking behavior and choice of TB treatment facility, and included: age, sex, HIV status, site of disease (pulmonary vs. extrapulmonary), lack of bacteriologic confirmation (positive sputum microscopy or GeneXpert), year of treatment, and treatment facility. We estimated the relative risk as a measure of association between unfavorable treatment outcomes and Euclidean distance, modeling distance both in four categories (with reference to the < 2 km category) and as binary, using simple and multivariable Poisson regression with robust variance. All risk factors of interest were included in the multivariable model regardless of statistical significance. We analyzed associations between travel distance and unfavorable treatment outcomes in similar fashion. In a sub-analysis, we also analyzed death and loss to follow up as separate outcomes compared to favorable treatment outcomes.

Results

Study population

From 2014 to 2016, 2251 patients initiated TB treatment at the six study facilities, of whom 2146 (95.3%) had a documented residential information in the Facility TB register. Patients came from 181 parishes in 28 districts throughout Uganda. We excluded 261 (12.2%) patients whose listed parish of residence information could not be matched to a parish listed in the 2014 Uganda Bureau of Statistics Census and an additional 16 participants from analyses of travel distance who could not be linked due to lack of road network connectivity. We excluded 109 (5.8%) TB patients who were transferred out as we were unable to determine their final treatment outcome. Among 1691 patients with reported outcomes, favorable treatment outcomes were seen in 1352 (80.0%) of TB patients; 85 (4.8%) TB patients had no documented treatment outcomes. Figure 1 shows the proportion of TB cases with unfavorable treatment outcomes by parish for Kampala District and surrounding areas.

Percentage of TB Cases with unfavorable treatment outcomes by Parish in Kampala1 District and surrounding areas, 2014–2016. 1 Parishes further outside Kampala not displayed. Dark line indicates Kampala District boundary. Parish boundaries and population provided by Uganda Bureau of Statistics. Maps created using ESRI ArcGIS 10.7.1

Facility TB notification rate

Average annual parish-level facility TB notification rates ranged from 0 to 327 TB cases per 100,000 population (Fig. 2). Facility notification rates decreased by 4% with each additional kilometer from the parish centroid to the health facility where the patient received TB treatment (rate ratio 0.96 [95% CI 0.95, 0.97]).

TB Facility Notification by Parish in Kampala District1 and surrounding areas for six Facilities serving Kisugu and Wabigalo Parishes2, 2014–2016 a. Annual Facility Notification Rate per 100,000 population (based on 2014 census). b. Total Count of Facility Notified TB Cases. 1 Parishes further outside Kampala not displayed. Dark line indicates Kampala District boundary. 2 Facility Notification Rates and Total Number of TB Cases Reported are from six study facilities providing TB treatment and do not represent all TB cases diagnosed at all facilities within each parish. Parish boundaries and population provided by Uganda Bureau of Statistics. Maps created using ESRI ArcGIS 10.7.1

Distance to TB treatment facility and treatment outcomes

The median Euclidean distance from the centroid of parish of residence to health facility where the patient chose to receive TB treatment was 3.7 km. While many patients lived < 2 km from their chosen facility (34%), nearly half of patients lived 2–10 km from their facility (49%), and 17% lived ≥10 km from their facility. Across the four distance exposure groups, there were differences in age, sex, HIV status, disease site, laboratory confirmation of disease, year of treatment initiation, and health facility (all p < 0.05) (Table 1). People living ≥2 km from the facility were more likely to be female (42% vs 34%), HIV positive (53% vs 46%), have extrapulmonary disease (17% vs. 8%), and lack bacteriologic confirmation of disease (37% vs. 24%) compared to those living < 2 km from the facility.

In simple and multivariable Poisson regression models, no significant association was seen between the four categories of distance and unfavorable treatment outcomes (Table 2). In analysis of a binary measure of distance, the adjusted relative risk [aRR] for unfavorable treatment outcomes was 0.87 (95% CI 0.70, 1.07) for patients who lived ≥2 km from the facility where they chose to receive TB treatment compared to those living within 2 km. Patients who were HIV positive (aRR 1.72 [95%CI 1.36, 2.17]), over the age of 65 years (aRR 2.53 [95%CI 1.59, 4.04]), or lacked bacteriologic confirmation of TB (aRR 1.57 [95%CI 1.27, 1.94]) were more likely to have unfavorable treatment outcomes. Patients aged less than 14 years (aRR 0.44 [95%CI 0.21, 0.90]) or receiving TB treatment at St. Francis Hospital-Nsambya (aRR 0.60 [95%CI 0.45, 0.80], compared to Kisugu Health Centre) had lower risk of unfavorable treatment outcomes.

In a sub-analysis evaluating death and loss to follow-up separately, distances of ≥2 km from residence to facility chosen for TB treatment were associated with an increased risk of death but decreased risk of loss to follow up (Table 3). Comparing those living ≥2 km from the facility to those living within 2 km, the adjusted RR for death was 1.42 (95% CI 0.99, 2.03) and the adjusted RR for loss to follow up was 0.57 (95% CI 0.41, 0.78). Risk factors for death included older age (55–64 years or 65+ years), being HIV positive, and lacking bacteriologic confirmation of disease (Table 3). We found no additional risk factors for loss to follow-up during TB treatment.

Travel distance

Travel distance using the shortest available route was strongly correlated with Euclidean distance (R2 = 0.98) but was on average 19% further than Euclidean distance (95% CI 18, 20%). While 31.1% of participants were reclassified to a different distance category if travel distance was used instead of Euclidean distance, there were no substantive differences in the association between distance from facility chosen for TB treatment and treatment outcomes when using travel distance as the exposure compared to Euclidean distance (Tables in supplement).

Discussion

This analysis of 1774 patients treated for TB across six urban clinics in the Makindye division of Kampala, Uganda, was suggestive of a protective association between longer distance from home to chosen treatment facility and composite unfavorable treatment outcomes. Facility notification rates for the included treatment facilities were high in parishes nearest to the facilities but were also high for some parishes far from the facilities. Nevertheless, despite the high density of TB treatment facilities in Kampala, 66% of patients starting TB treatment in these six facilities lived more than ≥2 km from the treating facilities (Table 1); compared to those who lived within 2 km of the facility, those living more remotely were 42% more likely to die but 43% less likely to be lost to follow-up.

Most patients in our study setting live within 2 km of multiple facilities and therefore can choose where they want to receive TB care. Patients may choose to seek care at a facility further away due to stigma against TB and a desire to hide their TB status [15,16,17], convenience due to work or other travel [18], or perception of better care, particularly at private facilities [18]. This dynamic may explain the differences seen when considering death versus loss to follow up as an outcome. Death during TB treatment in this setting (where multidrug resistance is uncommon) likely reflects a patient’s severity of illness when diagnosed, whereas loss to follow-up may more closely reflect patient motivation and health system investment. Thus, patients who choose to travel more than 2 km to be treated may be those who experience other barriers to seeking care (e.g., stigma, job-related time limitations, unease with the healthcare system) which can cause delays in diagnosis and treatment. Such delays are associated with increased disease severity [19] and higher corresponding mortality rates [20,21,22]. However, once treatment is initiated, these patients who are sicker and willing to travel longer distances may be more motivated to adhere to treatment, thereby reducing losses to follow-up. These findings illustrate how important distinctions between these two outcomes may be obscured when considering unfavorable treatment outcome as a composite measure.

Our study fills an important gap in knowledge regarding barriers to care and TB treatment outcomes. Prior studies have had mixed results regarding the effect of distance on delays in TB diagnosis and initiation of TB treatment [2,3,4]. Our study suggests that, once treatment is initiated, distance is not associated with overall unfavorable treatment outcomes. Other studies have highlighted economic, socio-cultural, and health system barriers to care in high-burden settings as access-related risk factors for poor treatment outcomes [23]; the current research suggests that geographic distance to treatment facility may not be a strong measure of access to care, particularly in the urban sub-Saharan African setting. Additionally, our finding that travel distance using the shortest available route does not change our results compared to using Euclidean distance is in contrast with other research [24]. This may reflect the high population density and informal road network in our setting, such that travel paths are generally direct and the differences between Euclidean and travel distances are small, particularly if walking or using boda bodas (motorbike taxis) for transport.

This analysis does have some key limitations, largely due to the limited data available in facility TB registers. For example, these registers do not contain data on precise address of residence, thus limiting our measurement of distance to that of the parish centroid. Nevertheless, on average, participants will live within 500 m of the parish centroid, making major bias at the scale of our distance categories less likely. Additionally, while Euclidean distance does not directly capture the distance traveled to seek care, our assessment of travel distance yielded comparable results. Due to the limited data available in the TB registers, we are unable to assess the contribution of broader barriers to health care access, including economic, socio-cultural, and health system barriers. These factors may overlap or interact with geographic barriers. Additionally, we could not assess patients’ reasons for choosing particular facilities; further qualitative research could help to elucidate these motivations. Our study includes patients attending facilities in a densely crowded urban area, and our findings may not generalize to other settings (e.g., rural areas) where facilities are further apart and patients have fewer treatment options. While we do not have complete capture of any geographic region (e.g., people living in Kisugu and Wabigalo parishes) due to our sampling frame based on health facilities, we do have full capture of every patient seeking care at these facilities. Our final models excluded more than 20% of TB cases seen at these facilities due to missing data on either residence or treatment outcome; while our sensitivity analysis showed no major effect of excluding those missing treatment outcomes, we may have selection bias if those included in our analysis are not representative of those missing residential information in regards to the association of distance on treatment outcomes. Finally, since we only considered patients enrolled in care, we could not assess the role of geographic barriers in limiting initial access to care.

Conclusion

Distance from home residence to TB treatment facility was not associated with overall unfavorable treatment outcomes in this urban Ugandan population, but was associated with increased risk of death and decreased risk of loss to follow up. These findings suggest that those who seek care further from home may do so at a more advanced disease state, but once enrolled they may be more likely to remain in treatment. This is important for TB control programs to consider, as they may need to invest in programs that decrease delays in diagnosis among those living further away and improving treatment adherence among those who live closer to facilities. A detailed understanding of the patient population and the varying experiences of that population is key to appropriately focusing resources to improve TB treatment outcomes.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used for this analysis is available on the Johns Hopkins University Data Archive (https://doi.org/10.7281/T1/LW2H2F).

Abbreviations

- aRR:

-

Adjusted relative risk

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- ESRI:

-

Environmental Systems Research Institute

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- REDCap:

-

Research electronic data capture

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Global tuberculosis report 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/274453?show=full. [cited 2019 Jun 19].

Botha E, Boon SD, Verver S, Dunbar R, Lawrence K-A, Bosman M, et al. Initial default from tuberculosis treatment: how often does it happen and what are the reasons? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12(7):820–823(4).

Edginton ME, Sekatane CS, Goldstein SJ. Patients’ beliefs: do they affect tuberculosis control? A study in a rural district of South Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis Off J Int Union Tuberc Lung Dis. 2002;6(12):1075–82.

Zegeye A, Dessie G, Wagnew F, Gebrie A, Islam SMS, Tesfaye B, et al. Prevalence and determinants of anti-tuberculosis treatment non-adherence in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14(1):e0210422.

Mayer CM, Owaraganise A, Kabami J, Kwarisiima D, Koss CA, Charlebois ED, et al. Distance to clinic is a barrier to PrEP uptake and visit attendance in a community in rural Uganda. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019 Apr;22(4):e25276.

Fluegge K, Malone LL, Nsereko M, Okware B, Wejse C, Kisingo H, et al. Impact of geographic distance on appraisal delay for active TB treatment seeking in Uganda: a network analysis of the Kawempe community health cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):798.

Ng’anjo Phiri S, Kiserud T, Kvåle G, Byskov J, Evjen-Olsen B, Michelo C, et al. Factors associated with health facility childbirth in districts of Kenya, Tanzania and Zambia: a population based survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:219.

Hanson C, Cox J, Mbaruku G, Manzi F, Gabrysch S, Schellenberg D, et al. Maternal mortality and distance to facility-based obstetric care in rural southern Tanzania: a secondary analysis of cross-sectional census data in 226 000 households. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(7):e387–95.

Okwaraji YB, Edmond KM. Proximity to health services and child survival in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2012;2(4):e001196.

Tadesse T, Demissie M, Berhane Y, Kebede Y, Abebe M. Long distance travelling and financial burdens discourage tuberculosis DOTs treatment initiation and compliance in Ethiopia: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:424.

Tripathy JP, Srinath S, Naidoo P, Ananthakrishnan R, Bhaskar R. Is physical access an impediment to tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment? A study from a rural district in North India. Public Health Action. 2013;3(3):235.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81.

Uganda Bureau of Statistics. Parish Level Profiles (Census 2014). Available from: https://www.ubos.org/explore-statistics/20/. [cited 2019 Jun 18].

Wynne A, Richter S, Jhangri GS, Alibhai A, Rubaale T, Kipp W. Tuberculosis and human immunodeficiency virus: exploring stigma in a community in western Uganda. AIDS Care. 2014;26(8):940–6.

Buregyeya E, Kulane A, Colebunders R, Wajja A, Kiguli J, Mayanja H, et al. Tuberculosis knowledge, attitudes and health-seeking behaviour in rural Uganda. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis Off J Int Union Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15(7):938–42.

Katamba A, Neuhauser DB, Smyth KA, Adatu F, Katabira E, Whalen CC. Patients perceived stigma associated with community-based directly observed therapy of tuberculosis in Uganda. East Afr Med J. 2005;82(7):337–42.

Kapwata T, Morris N, Campbell A, Mthiyane T, Mpangase P, Nelson KN, et al. Spatial distribution of extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (XDR TB) patients in KwaZulu-Natal. South Africa PloS One. 2017;12(10):e0181797.

Godfrey-Faussett P, Kaunda H, Kamanga J, van Beers S, van Cleeff M, Kumwenda-Phiri R, et al. Why do patients with a cough delay seeking care at Lusaka urban health centres? A health systems research approach. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis Off J Int Union Tuberc Lung Dis. 2002;6(9):796–805.

Lisboa M, Fronteira I, Colove E, Nhamonga M, Martins M do RO. Time delay and associated mortality from negative smear to positive Xpert MTB/RIF test among TB/HIV patients: a retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):18.

Adamu AL, Gadanya MA, Abubakar IS, Jibo AM, Bello MM, Gajida AU, et al. High mortality among tuberculosis patients on treatment in Nigeria: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):170.

Lee C-H, Wang J-Y, Lin H-C, Lin P-Y, Chang J-H, Suk C-W, et al. Treatment delay and fatal outcomes of pulmonary tuberculosis in advanced age: a retrospective nationwide cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):449.

Alipanah N, Jarlsberg L, Miller C, Linh NN, Falzon D, Jaramillo E, et al. Adherence interventions and outcomes of tuberculosis treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis of trials and observational studies. PLoS Med. 2018;15(7):e1002595.

Ross JM, Cattamanchi A, Miller CR, Tatem AJ, Katamba A, Haguma P, et al. Investigating barriers to tuberculosis evaluation in Uganda using geographic information systems. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;93(4):733–8.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff and patients at Kisugu Health Center, Alive Medical Services, International Hospital Kampala, Kibuli Muslim Hospital, Nsambya St. Francis Hospital, and Meeting Point Clinic for their participation.

Funding

This research was funded by the Johns Hopkins Center for Global Health Established Field Placement and the US National Institutes of Health (R01HL138728). The funding sources had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, or the writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KR, SH, DWD, and AK contributed to the conception and design of the study. KR, SH, and AK collected the data. KR, SH, and DWD conducted statistical analysis. KR and DWD drafted the manuscript. SH, AK, EAK, and PJK contributed to analysis, interpretation, and subsequent manuscript revisions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board (IRB Number 7939) and the Ethics Review Committee of the Makerere University School of Public Health (HDREC Protocol 503). A waiver of informed consent was granted for this retrospective chart abstraction.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Supplemental Results.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Robsky, K.O., Hughes, S., Kityamuwesi, A. et al. Is distance associated with tuberculosis treatment outcomes? A retrospective cohort study in Kampala, Uganda. BMC Infect Dis 20, 406 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05099-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05099-z