Abstract

Background

Drug resistant tuberculosis (TB) has become a persistent health threat in Ethiopia. In this respect, baseline data are scarce in many parts of high TB burden regions including the different zones of Ethiopia.

Methods

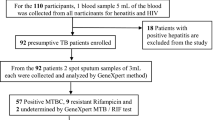

A total of 111 culture positive M. tuberculosis isolates were recovered from TB patients and identified using region of difference (RD) 9 based polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and spoligotyping. Thereafter, their drug sensitivities to Rifampicin (RIF) and Isoniazid (INH) were evaluated using GenoType MTBDRplus assay.

Results

The result showed that 18.0% (20/111) of the isolates were resistant to either RIF or INH. Furthermore, 16.7 and 23.8% of the isolates from new and retreatment cases were resistant to any of the two anti-TB drugs, respectively. Multi-drug resistant (MDR) TB was detected on 1.8% (2/111) of all cases. Significantly higher frequencies of any drug resistance were observed among Euro-American (EA) major lineage (χ2: 9.67; p = 0.046).

Conclusion

Considerably high proportion of drug resistant M. tuberculosis strains was detected which could suggest a need for an increased effort to strengthen TB control program in the study area.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease caused by M. tuberculosis complex and persists to be a public health threat globally. In 2016, there were an estimated 10.4 million incident cases and about 25% of which were inhabitants of Africa [1]. In Ethiopia, the estimated total TB incidence in 2016 was 177 per 100,000 population. This was greater than the global average of 140 /100,000 [1].

Drug resistant TB remains to be a public health threat in many parts of the world. About 490,000 cases of multidrug resistant-TB (MDR-TB) and an additonal 110, 000 cases that were susceptible to INH but resistant to RIF, RR-TB; the most effective first-line anti-TB drug were reported at the end of 2016 [1]. According to the same report, an estimated 4.1% of new cases and 19% of previously treated cases had MDR/RR-TB. In this respect, Ethiopia has reported a relatively lower level of drug resistant-TB (DR-TB) cases than the global average, 2.7% resistance in newly diagnosed and 14% of previously treated cases, respectvely [1].

Many separate studies in Africa suggested the public health risk of drug resistant-TB. A study conducted in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, reported 72.9% of the M. tuberculosis isolates were resistant to at least one of the first-line anti-TB drugs [2]. A similar study in Oromia region of the country, reported 33% of the cases were MDR-TB [3]. Studies from other parts of Africa such as South Africa, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Uganda, Tanzania and Kenya reported significant proportions of M. tuberculosis isolates were resistant to at least one of the first-line anti-TB drugs [4,5,6,7,8,9].

In the Amhara region of northwest Ethiopia, drug resistance remains to be one of the major obstacles to the effort towards effective TB control. Previous studies in the region suggested a high (ranging from 15.8 to 33.5%) resistance level of M. tuberculosis for at least one of the currently available first-line anti-TB drugs which was affected by different patient and microbial characteristics [10,11,12]. However, no enough data is available in this respect in different zones of the region. Therefore, the present study was conducted to determine anti-TB drug resistance and its associated risk factors in South Gondar Zone of the Amhara Region, northwest Ethiopia.

Methods

The study area

The study was conducted in South Gondar Zone of the Amhara Region, northwest Ethiopia. Debre Tabor is the seat of the administration of the Zone and is located at 666 km from Addis Ababa in the northwest direction and at 99 km from Bahir Dar City in the same direction. The Zone consisted of 10 districts and inhibited by 2,051,738 people. The population density of the Zone was 145.56 per square km; 90.47% of its population was living in the rural area. The total number of households in the Zone were 468,238 and average number of persons per a household was 4.38 [13]. The livelihood of the community largely depended on subsistence agriculture [14].

Study design and participants

A cross-sectional study was conducted between March 2015 and April 2017 to determine anti-TB drug sensitivity of M. tuberculosis isolated from TB cases in the South Gondar Zone. All forms (pulmonary and extra pulmonary) TB cases who visited the health centers, zonal and regional referal hospitals were included in this study. All extra pulmonary cases were TB lymphadenitis. TB patients who were under treatment prior to the start of the study and those under 5 years of age were excluded from the study.

Data collection and processing

After informed consent was obtained from participants, sputum samples and fine needle aspirate (FNA) samples were collected by trained laboratory technicians and pathologists.

The samples were first digested and concentrated/decontaminated by the N-acetyl-L-cysteine-Sodium hydroxide (NALC-NaOH) method. Smears of the final deposits from the various specimens were stained by the Ziehl-Neelsen (ZN) method and examined under oil immersion using a binocular light microscope. All smear positive TB samples were stored at + 4 °C at the study site and then transported to Regional Health Research Llaboratory Center (Bahirdar) and kept at + 4 °C until bacteriological culture was performed.

FNA samples were collected by pathologsts using standard needle and syringes and stored in cryo-tubes with phosphate buffer saline (PBS) pH 7.2. ZN staining was used to detect acid-fast/ tubercule bacilli (AFB). The AFB-positive samples were stored in a similar way to that of sputum samples for further investigations.

Mycobacterium culture

The samples were processed for culturing according to the standard methods described earlier [15, 16]. Both sputum and FNA samples were cultured at the Bahir Dar Regional Health Research Laboratory Centre. Briefly, about 100 μl of the sample suspension was inoculated on four sterile Lowenstein Jensen (LJ) medium slopes (two were supplemented with pyruvate and the other two with glycerol) and then incubated at 37 °C with weekly examination for growth. Cultures were considered to be negative when no visible growth was detected after eight weeks of incubation. The presence of AFB in positive cultures was detected by smear microscopic exa-mination using the ZN staining method. AFB positive cultures were prepared as 20% glycerol stocks and stored at − 80 °C as reference. Heat-killed cells of each AFB isolate were prepared by mixing ~ 2 loopfuls of cells (≥ 20 μl cell pellet) in 200 μl distilled H2O followed by incubation at 80 °C for 45 min for the release of DNA after the breaking the cell wall. The heat killed cells were transported to the laboratory at Aklilu Lemma Institute of Pathobiology, Addis Ababa University, for molecular typing.

Region of difference (RD) 9-based polymerase chain reaction

To differentiate M. tuberculosis from other members of the M. tuberculosis complex (MTBC) species, RD9 based PCR was performed according to protocols previously described [17].

M. tuberculosis H37Rv, M. bovis bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) were included as positive controls and water was used as a negative control. Interpretation of the result was based on bands of different sizes (396 base pairs (bp) for M. tuberculosis and 375 bp for M. bovis) as previously described [18].

Spoligotyping

Isolates genetically identified as M. tuberculosis were spoligotyped for further strain identification. Spoligotyping makes use of the variability of the MTBC chromosomal direct repeat (DR) locus for strain differentiation as previously described [19]. A PCR-based amplification of the DR region of the isolate was performed using oligonucleotide primers derived from the DR sequence. The amplified product was hybridized followed by subsequent membrane washing processes. Known strains of M. bovis and M. tuberculosis H37Rv were used as positive controls, whereas Qiagen water (Qiagen Company, Germany) was used as a negative control. Hybridized DNA was detected by the enhanced chemiluminescence method. The presence or absence of spacer was used as key for the interpretation the result.

Identification of M. tuberculosis strains and lineages

A web-based spoligotype database was utilized to assign shared international types (SITs) for the isolates [20]. Strains matching a preexisting pattern in the database were identified with SIT number otherwise considered as orphans. An online TB lineage tool was used to predict the major lineages using a conformal Bayesian network (CBN) analysis and sub lineage/family using knowledge based Bayesian network (KBBN) [21].

Drug sensitivity test (DST) by molecular method

The GenoType MTBDRplus assay which is a molecular genetic assay was used to detect resistant M. tuberculosis isolates to RIF and INH. The assay is based on the DNA-STRIP technology. The whole procedure involves a multiplex PCR amplificaton with biotinylated primers, and a reverse hybridization. This assay detects for the abscence and/or presence of wild type (WT) and/or mutant (MUT) DNA sequences with in specific region of three genes: the rpoB gene (coding for the β-subunit of the RNA polymeraze), for the identification of RMP resistance; the katG gene (coding for the catalase peroxidase), for high level INH resistance; and the promoter region of the inhA gene (coding for the NADH enoylACP reductase), for low-level INH resistance. The procedure of the test was performed based on the manufacturer’s instructions (Hain Life sciences, Nehren, Germany).

Data analysis

Data were double entered to Excile file format and statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 25. Descriptive statistics were used to depict the demographic variables. Bivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to obtain crude odds ratio (COR) and the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) to assess the association of risk factors and the odds of drug sensitivity. The Pearson Chi-square (χ2) was calculated to test the association of drug resistance with genotype of M. tuberculosis isolates from TB patients. Results were considered statistically significant whenever p-value was less than 5%.

Results

Drug resistance patterns among the different patient characteristics

The drug sensitivity test was performed for 111 culture positive M. tuberculosis isolates obtained from both pulmonary and extra pulmonary TB patients. Of which, 91 (82.0%) were susceptible to both RIF and INH and 20 (18.0%) were resistant to atleast one of the two drugs. Of the total 20 drug resistant isolates, the male to female ratio was 1:1. Younger adults aged between 18 and 30 years constituted about 45% (9/20) of the total drug resistant cases (see Table 1).

Of 90 newly diagnosed TB cases, 75 (83.3%) were susceptiable to both RIF and INH (RIFs, INHs) but the remaining 15 (16.7%) were INH mono-resistant (RIFs, INHr). Similarly, 23.8% (5/21) of the retreatment cases were resistance to either of RIF and INH (see Table 1).

Despite the observed differences in the proportions of drug resistant cases, no statistically significant association was observed between demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with drug resistance. From a total of 21 retreatment TB cases, 76.2% (16/21) were suscebtible to both drugs and the remaining 23.8% (5/21) were resistant to atleast one of the two anti-TB drugs (see Table 1).

MDR-TB cases (resistance to both RIF and INH) were observed in 1.8% (2/111) of the cases. Both cases were detected from retreatment TB patients. No RIF mono-resistant (RIFr, INHs) case was detected in any of disease or patient categories (see Table 2).

Drug resistance confering gene mutations

From the total samples tested for drug sensitivity, 18.0% (20/111) of them showed atleast one gene mutation. Among the three targeted genes (katG, rpoB and inhA), mutations were observed only on the katG and rpoB genes, confering a high level of INH resistance and RIF resistance, respectively. All INH-resstance confering mutations occured only at katG gene (katG MUT1). In the present study, no inhA gene mutaion was observed. About 1.8% (2/111) RIF-resistance confering gene mutations occured and resulted from the absence of rpoB WT7, without the presence of MUT3 in both specimens. Both the RIF-resistance confering gene mutations at probB occured together with INH-resistance confering gene mutations at katG genes, signaling MDR-TB pattern. Among the 20 INH-resistance confering mutations, specific mutations (the WT probe was missed with the presence of the corresponding MUT1 probe) of the katG gene were observed in 12 isolates. In 6 INH-resistant isolates, unexpected mutation patterns were observed, both the WT and the corresponding MUT1 probes of the katG gene were positive signaling a hetroresistance pattern and considered as ‘rare’ mutations (see Table 3). WT7 probes of the proB gene were missed without the presence of the corresponding MUT probes and considered as ‘unknown’ mutations (see Table 3).

RD9 deletion typing patterns of M. tuberculosis strains

A total of 106 culture-positive mycobacterial isolates were tested by RD9-based PCR. The test revealed that all isolates had intact RD9 locus and were subsequently classified as M. tuberculosis. No other species of MTBC was detected.

Spoligotype patterns of M. tuberculosis strains

The patterns of 96 isolates were interpretable and grouped into 38 different spoligotype patterns. From the 38 patterns, 22 were shared types and consisted of 76 isolates. The remaining 16 were not registered in the database and were ‘orphans’ strains. The dominantly identified SITs were SIT53, SIT149, and SIT428, each consisting of 18, 12 and 12 isolates, respectively. These three SITs consisted of 43.8% of the total isolates.

Five major lineages were identified including Euro-American (EA), East-African-Indian (EAI), M. africanum, Indo-Oceanic (IO), and East-African-Asian (EAS), each consisting of 65.5, 26, 8.3, 2.1 and 1% of the isolates, respectively. The three dominantly identified families were T, CAS and Manu, each consisting of 46.9, 24.0 and 10.4% of the isolates, respectively.

Association of drug resistance pattern and M. tuberculosis lineages

The majority of resistant strains for any of anti-TB drugs (RIF, INH, RIF and INH) were belong to the EA major lineage, 16.7% (16/96), sub-lineage T,10.4% (10/96), orphan dominant strains, 6.3% (6/96) and clustered strains, 13.5% (13/96). The two MDR cases belonged to the EA major lineage and T3-ETH sub-lineage.

A statistically significant association (χ2: 9.67; p = 0.046) was observed between any anti-TB drug resistance and major lineages of M. tuberculosis strains. Although the statistical association between the categories of sub-lineages, dominant strains and clustering level with any drug resistance of the isolates was not significant, differences in proportion were observed (see Table 4).

Discussion

In the present study, an over all resistance of 18.0% (20/111) was detected for either of RIF and INH. This was comparable with a previous study conducted in Southwest Ethiopia [22]. Similarly, an 18.4% [23] and 17.8% [12] resistance levels were reported in Eastern and northeastern Ethiopia, respectively. However, lower resistance levels to one of the first line anti-TB drugs were reported in the northwest (15.3%) [10] and northern (6.7%) [24] parts of the country, respectively. In contrast, higher resistance levels (ranged from 22 to 35.5%) than the present study were reported in different parts of the country [2, 11, 25,26,27]. Higher anti-TB resistance was also reported in some other East African countries such as Kenya (30%) and Rwanda (43%) [28, 29]. The observed differences in the level of anti-TB drug resistance between this study and previous studies might be due to dfferences in study settings, study design and sample size. Most of our study particpants were all forms of TB patients from rural areas and the majority (81.1%) of the study subjects were newly diagnosed, which might lower the intensity and transmission of drug resistant TB as compared to the urban and prison settings in the previous studies where higher chance of TB circulation and lower anti-TB drugs adherence could be noticed.

The 16.2% (18/111) INH monoresistance recorded in the present study was higher than those reported in other parts of Ethiopia [30, 31]. Lower prevalence of INH monoresistance was also reported in other East African countries such as Kenya (3.1%) and Tanzania (6.3%) [9, 32]. Similarly, lower levels of INH monoresistance cases were reported in Pakistan (6.3%) and south India (6.9%) [33, 34]. In contrast, higher levels of INH monoresistance were reported by other studies in Kenya (30.2%), Ethiopia (27.7%) and Guinea (18%) [28, 35, 36]. Repeated use of the drug and patients lower adherance to the antibiotc might be responsible for the overall higher INH monoresistance level in the present study.

In this study, the low prevalences (1.8%) of MDR-TB was comparable with previous studies conducted in Ethiopia [26, 27, 37]. However, higher levels of MDR-TB cases were revealed in Oromia region (33%) and southwest Ethiopia (27.7%) [3, 38]. Studies conducted in Uganda (14%) and Tanzania (6.3%) reported higher frequencies of MDR-TB cases among new TB cases [5, 7]. All the above investigations were cross-sectional studies but the dfferences in overall prevalence of MDR-TB might be due to variation in the number of samples and selection of the study subjects. Samples from TB-specialized hospitals and the majority of retreatment cases could increase the number of MDR-TB cases unlike the present study where the majority samples were from rural dwellers in government health centers and peripheral health posts and about 81% of the study subjects were newly diagnosed for TB.

In the present study, we observed a complete preference of katG mutations without concurrent inhA promoter mutation. All (20/111) the anti-TB drug resistant strains were resistant to INH, and all the INH-resistance had resulted because of mutations at katG gene. In agreement to our findng, a study conducted in another part of the Amhara region reported that all the INH-resistant isolates were due to mutations at katG gene [24]. Higher frequencies of katG mutations were also reported in other parts of Ethiopia [23, 38, 39]. All the above facts suggested the emergence of high level INH-resistnce among M. tuberculosis strains circulating in the study area which potentially could compromise TB treatment and control.

In our study, exceptions to specifc mutation patterns were observed. In six INH-resistant M. tuberculosis isolates, unusual or rare mutation pattern was noticed at katG gene in which both the katGWT and katGMUT types were present simultaneously, signaling hetroresistance condition. Moreover, in the two MDR-TB cases, the WT7 probes of the proB gene were missed without the presence of the corresponding MUT probes and considered as ‘unknown’ mutations. Both these unexpected mutation patterns were also reported in several studies in Ethiopia [38, 39]. The hetroresistant cases might be due to selection of cells with random mutatons during inadequate treatment or by mixed infections with sensitive and resistant cells. This hetroresistance phenomenon will jeoparadize the effective treatment of patients with INH there by leading to the development of anti-TB drug resistance in the study area.

In this study, any drug resistance to RIF and INH was not found to be proportionally distributed among M. tuberculosis genotypes. However, a statistically significant association was observed between any types of anti-TB drug resistance and EA lineage. Similarly, a higher frequency of any drug resistance to first line anti-TB drugs among EA lineage of M. tuberculosis was reported in central Ethiopia [27]. Although the association was not statistically significant, the observed highest proportion of drug resistant cases among the T-sublineage investgated in this study was similar to studies from other African countries, Tanzania [32] and Uganda [40]. In this study, clustered strains showed higher frequency of any anti-TB drug resistance, suggesting higher risk of drug resistance in recent TB transmission in the study area.

Conclusions

Considerable proportion of M. tuberculosis strains was found to be resistant to at least one of RIF and INH. Significant variatons were observed in drug resistance patterns among M. tuberculosis lineages. Therefore, increased efforts in timely evaluatlon of drug resistance and application of more roboust diagnostic tools may help in the implementation of effective TB control program in the study area.

Limitations

Although our study wass the first report concerning the gentetic basis of drug resistance and its association of genotypes among M. tuberculosis isolates circulatng in south Gondar zone, northwest Ethiopia, it had some limitations. The molecular detection of drug resistance among M. tuberculosis isolates was not compared with the routinely used conventional drug sensitivity method. In addition, molecular characterization of mycobacterial strains was not conducted using better molecular diagnostic tools than spoligotypng.

Abbreviations

- AFB:

-

Acid-fast bacilli

- CBN:

-

Conformal Bayesian network

- EA:

-

Euro-American

- EAI:

-

East-African-Indian

- EAS:

-

East-African-Asian

- FNA:

-

Fine needle aspirate

- INH:

-

Isoniazid

- IO:

-

Indo-Oceanic

- KBBN:

-

Knowledge based Bayesian network.

- LJ:

-

Lowenstein- Jensen

- MDR:

-

Multi-drug resistance

- MIRU:

-

Mycobacterial interspersed repetitive units

- MTBC:

-

Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex

- MUT:

-

Mutant

- PBS:

-

Phosphate buffer saline

- PCR:

-

Polymeraze chain reaction

- RD:

-

Region of difference

- RIF:

-

Rifampisin

- RR:

-

Rifampisin resistance

- SIT:

-

Spoligotype International Type

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

- WT:

-

Wild type

- XDR:

-

Extensively drug-resistant

References

WHO. Global tuberculosis report 2017. World Health Organization. Geneva, Swizerland, available at: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/ accessed date [26/10/2017].

Abate D, Taye B, Abseno M, Biadgilign S. Epidemiology of anti-tuberculosis drug resistance patterns and trends in tuberculosis referral hospital in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:462.

Mulisa G, Workneh T, Hordofa N, Suaudi M, Abebe G, Jarso G. Multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis and associated risk factors in Oromia region of Ethiopia. Inter J Infect Dis. 2015;39:57–61.

Silaigwana B, Green E, Ndip R. Molecular detection and drug resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex from cattle at a dairy farm in the Nkonkobe region of South Africa: a pilot study. Int J Environ Res Pub Heal. 2012;9:2045–56.

Lukoye D, Adatu F, Musisi K, Kasule G, Were W, Odeke R, et al. Anti-tuberculosis drug resistance among new and previously treated sputum smear-positive tuberculosis patients in Uganda: results of the first National Survey. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e70763. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0070763.

Sagonda T, Mupfumi L, Manzou R, Makamure B, Tshabalala M, Gwanzura L, et al. Prevalence of extensively drug resistant tuberculosis among archived multidrug resistant tuberculosis isolates in Zimbabwe. Tuberc Res Treat. 2014. Available at. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/349141 Accessed date [30/11/2017.

Hoza A, Mfinanga S, König B. Anti-TB drug resistance in Tanga, Tanzania: a cross sectional facility-base prevalence among pulmonary TB patients. Asian Paci J Trop Med. 2015;8(11):907–13.

Kapata N, Mbulo G, Cobelens F, Haas P, Schaap A, Mwamba P, et al. The second Zambian National Tuberculosis Drug Resistance survey –a comparison of conventional and molecular methods. Trop Med Inter Heal. 2015;20(11):1492–500.

Ombura I, Onyango N, Odera S, Mutua F, Nyagol J. Prevalence of drug resistance Mycobacterium tuberculosis among patients seen in coast provincial general hospital, Mombasa, Kenya. PLoS One 2016; 11(10): e0163994. doi:10.1371/.

Mekonen M, Abate E, Aseffa A, Anagaw B, Elias D, Hailu E, et al. Identification of drug susceptibility pattern and mycobacterial species in sputum smear positive pulmonary tuberculosis patients with and without HIV co-infection in north West Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2010;48(3):203–10.

Esmael A, Ali I, Agonafir M, Endris M, Getahun M, Yarega Z, et al. Drug resistance pattern of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in eastern Amhara regional state, Ethiopia. Microb Biochem Technol. 2014;6:2.

Maru M, Mariam S, Airgecho T, Gadissa E, Aseffa A. Prevalence of tuberculosis, drug susceptibility testing, and genotyping of mycobacterial isolates from pulmonary tuberculosis Patientsin Dessie, Ethiopia. Tubercul Res Treat. 2015. Available at. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/215015.

CSA. Central Statistics Agency, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Summary and Statistical Report of the 2007. Population and housing census: population size by age and sex. 2007. Available at:https://www.scribd.com/doc/28289334/Summary-and-Statistical-Report-of-the-2007. Accessed 9 Aug 2016.

EDHS. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey: Central statistical Agency, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and ICF international Calverton, Maryland, USA. 2011. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/ethiopia/ET_2011_EDHS.pdf. Accessed 4 May 2017.

WHO. Laboratory Services in Tuberculosis Control: Culture. Part III, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. 1998. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/65942/1/WHO_TB_98.258_.pdf. Accessed 14 Feb 2016.

FMoH. Federal Ministry of Health of Ethiopia. Tuberculosis, Leprosy and TB/HIV Prevention and Control Programme. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. 2008. Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/ethiopia_tb.pdf. Accessed 3 Feb 2016.

Berg S, Firdessa R, Habtamu M, Gadisa E, Mengistu A. Yamuah, et al. the burden of mycobacterial disease in Ethiopian cattle: implications for public health. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5068.

Parsons ML, Brosch R, Stewart T, Somoskövi A, Loder A, Bretzel G, et al. Rapid and simple approach for identification of Mycobacterum tuberculosis complex isolates by PCR-based genomic deletion analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:2339–45.

Kamerbeek J, Schouls L, Kolk A, Van Agterveld M, Van Soolingen D, Kuijper S, et al. Simultaneous detection and strain differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for diagnosis and epidemiology. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35(4):907–14.

The Spoligotype International Database. http://www.pasteur guadeloupe.fr:8081/SITVITDemo/. Accessed 10 Apr 2017.

Run TB-Lineage tool. http://tbinsight.cs.rpi.edu/run_tb_lineage.html. Accessed 14 Apr 2017.

Abebe G, Abdissa K, Abdissa A, Apers L, Agonafir M, de-Jong BC, et al. Relatively low primary drug resistant tuberculosis in southwestern Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:225.

Brhane M, Kebede A, Petros Y. Molecular detection of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis among smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Jigjiga town, Ethiopia. Infect Drug Resis. 2017;10:75–83.

Biadglegne F, Tessema B, Rodloff A, Sack U. Magnitude of gene mutations conferring drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from lymph node aspirates in Ethiopia. Int J Med Sci. 2013;10(11):1589–94.

Seyoum B, Demissie M, Worku A, Bekele S, Aseffa A. Prevalence and drug resistance patterns of Mycobacterium tuberculosis among new smear positive pulmonary tuberculosis patients in eastern Ethiopia. Tuberc Res Treat. 2014. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/753492; Accessed date [24/7/2017.

Ali S, Beckert P, Haileamlak A, Wieser A, Pritsch M, Heinrich N, et al. Drug resistance and population structure of M. tuberculosis isolates from prisons and communities in Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:687.

Bedewi Z, Mekonnen Y, Worku A, Medhin G, Zewde A, Yimer G, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Central Ethiopia: drug sensitivity patterns and association with genotype. New Microbe New Infect. 2017;17:69–74.

Ndung’u P, Kariuki S, Ng’ang’a Z, Revathi G. Resistance patterns of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Nairobi. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2012;6(1):33–9.

Gafirita J, Umubyeyi A, Asiimwe B. A first insight into the genotypic diversity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from Rwanda. BMC Clin Pathol. 2012;12:20.

Hamusse S, Teshome D, Hussen M, Demissie M, Lindtjørn B. Primary and secondary anti-tuberculosis drug resistance in Hitossa District of Arsi zone, Oromia regional state, Central Ethiopia. BMC Pub Heal. 2016;16:593.

Zewdie O, Mihret A, Abebe T, Kebede A, Desta K, Worku A, et al. Genotyping and Molecular Detection of Multi Drug Resistance Mycobacterium tuberculosis among Tuberculosis Lymphadenitis cases in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. New Microb New Infect. 2017.Availableat:http://www.sciencedirect.com. Aaccessed date [2/11/2017].

Kibiki G, Mulder B, Dolmans W, de Beer J, Boeree M, Sam N, et al. M. tuberculosis genotypic diversity and drug susceptibility pattern in HIV- infected and non-HIV-infected patients in northern Tanzania. BMC Microbiol. 2007;7:51.

Ayaz A, Hasan Z, Jafri S, Inayat R, Mangi R, Channa A, et al. Characterizing Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from Karachi, Pakistan: drug resistance and genotypes. Inter J Infect Dis. 2012;16:e303–9.

Shanmugam S, Selvakumar N, Narayanan S. Drug resistance among different genotypes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolated from patients from Tiruvallur, SouthIndia. Infect, Gen Evol. 2011;11:980–6.

Getahun M, Ameni G, Kebede A, Yaregal Z, Hailu E, Medihn G, et al. Molecular typing and drug sensitivity testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolated by a community-based survey in Ethiopia. BMC Pub Heal. 2015;15:751.

Ejo M, Gehre F, Barry M, Sow O, Bah N, Camara M, et al. First insights into circulating Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex lineages and drug resistance in Guinea. Infect Gen Evol. 2015;33:314–9.

Gebeyehu M, Lemma E, Eyob G. Prevalence of drug resistant tuberculosis in Arsi zone, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Heal Dev. 2001;15:11–6.

Tadesse M, Aragaw D, Dimah B, Efa F, Abdella K, Kebede W, et al. Drug resistance-conferring mutations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis from pulmonarytuberculosis patients in Southwest Ethiopia. Inter J Mycobacteriol. 2016;5:185–91.

Bedewi ZO, Mekonnen Y, Worku A, Zewde A, Medhin G, Mohammed T, et al. Evaluation of the GenoType MTBDRplus assay for detection of rifampicin- and isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates in Central Ethiopia. Inter J Mycobacteriol. 2016;5:475–81.

Bazira J, Asiimwe B, Joloba M, Bwanga F, Matee M. Mycobacterium tuberculosis spoligotypes and drug susceptibility pattern of isolates from tuberculosis patients in South-Western Uganda. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:81.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Addis Ababa University and the NIH (USA) for sponsoring this study. We also would like to thank all laboratory working staff and administrators at the Regional Health research Center, Bahirdar and ALIPB, Addis Ababa University, for their support in the development of this study. We also greatly thank health officials, laboratory workers and study participants in the study area, without whom this study would have not been completed.

Funding

The financial support for the study’s data collection, analyzing and writing up the research paper was obtained from Addis Ababa University through its thematic research program (Grant Ref. No. 0162230106072100101) and the study was partially supported by the National Institute of Health (NIH, USA) through its H3Africa Consortium Program (Grant Ref. No. U01HG007472–01).

Availability of data and materials

All the datasets on which our conclusions relayed on were presented in the main section of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AA: conceived the study, undertook the field and laboratory works and statistical analysis, and made major contribution in drafting and writing the manuscript. AZ and TM: made major contribution in the spoligotyping of M. tuberculosis isolates. ST: contributed a lot in the drug sensitivity test. GA: initiated the study and made major contribution in the study design, editing and follow up the development of the research BP: contributed in editing the paper and advising on the development of this work. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the Ethical Committee of Addis Ababa University, Department of Microbial, Cellular and Molecular Biology (Ref. CNSDO/491/07/15). In addition, written permission was sought from the Amhara Regional Health Bureau Research Ethical Committee (Ref. HRTT/1/271/07). Each study participant was consented with a written form and agreed to participate in the study after a clear explanation of the study objectives and patient data confidentiality. In case of study participants less than 18 years old, their parents or guardians were consented.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no any competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Alelign, A., Zewude, A., Mohammed, T. et al. Molecular detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis sensitivity to rifampicin and isoniazid in South Gondar Zone, northwest Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis 19, 343 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-3978-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-3978-3