Abstract

Background

Drug resistant tuberculosis (TB) is increasing in prevalence worldwide. Treatment failure and relapse is known to be high for patients with isoniazid resistant TB treated with standard first line regimens. However, risk factors for unfavourable outcomes and the optimal treatment regimen for isoniazid resistant TB are unknown. This cohort study was conducted when Vietnam used the eight month first line treatment regimen and examined risk factors for failure/relapse among patients with isoniazid resistant TB.

Methods

Between December 2008 and June 2011 2090 consecutive HIV-negative adults (≥18 years of age) with new smear positive pulmonary TB presenting at participating district TB units in Ho Chi Minh City were recruited. Participants with isoniazid resistant TB identified by Microscopic Observation Drug Susceptibility (MODS) had extended follow-up for 2 years with mycobacterial culture to test for relapse. MGIT drug susceptibility testing confirmed 239 participants with isoniazid resistant, rifampicin susceptible TB. Bacterial and demographic factors were analysed for association with treatment failure and relapse.

Results

Using only routine programmatic sputum smear microscopy for assessment, (months 2, 5 and 8) 30/239 (12.6%) had an unfavourable outcome by WHO criteria. Thirty-nine patients were additionally detected with unfavourable outcomes during 2 year follow up, giving a total of 69/239 (28.9%) of isoniazid (INH) resistant cases with unfavourable outcome by 2 years of follow-up. Beijing lineage was the only factor significantly associated with unfavourable outcome among INH-resistant TB cases during 2 years of follow-up. (adjusted OR = 3.16 [1.54–6.47], P = 0.002).

Conclusion

One third of isoniazid resistant TB cases suffered failure/relapse within 2 years under the old eight month regimen. Over half of these cases were not identified by standard WHO recommended treatment monitoring. Intensified research on early identification and optimal regimens for isoniazid resistant TB is needed. Infection with Beijing genotype of TB is a significant risk factor for bacterial persistence on treatment resulting in failure/relapse within 2 years. The underlying mechanism of increased tolerance for standard drug regimens in Beijing genotype strains remains unknown.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M.tuberculosis) is increasing worldwide and represents a major challenge to global TB control efforts. In 2015, there were 10.4 million new tuberculosis infections and 1.4 million deaths [1]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 17% of strains are now resistant to one or more of the major first line drugs [2]. Six percent of new TB cases and 20% of retreatment cases are multi-drug resistant (MDR TB) [2]. Multidrug resistant TB (MDR TB) is defined as resistance to at least isoniazid and rifampicin, the two most effective drugs in anti-tuberculous regimens. MDR TB must be treated with second-line drug regimens which are longer in duration, highly toxic, less potent and more expensive.

Rifampicin mono-resistance is rare and resistance to isoniazid is therefore the key precursor in the generation of MDR TB strains yet has received limited research attention. Ten percent of new TB cases and one third of retreatment cases globally are resistant to INH [2]. It is known from meta-analysis of trial data that treatment failure and relapse rates are higher among patients with undiagnosed INH resistance, yet the majority of these patients are still successfully treated using standard regimens [3,4,5,6,7]. The determinants of failure and relapse in those with INH resistance who fail despite good adherence to standard therapy are not well understood.

In Vietnam, as in most high burden settings, full drug resistance testing is only carried out for failure or retreatment cases and therefore isoniazid resistance is rarely detected in new TB cases. However, high treatment failure rates in isoniazid resistant TB cases may be fuelling the rise in MDR TB.

WHO has recommended that ethambutol (EMB) is added to the continuation phase for all new patients in countries with ‘high’ isoniazid resistance [8]. There is limited evidence for the efficacy of this regimen and the ocular toxicity of ethambutol will lead to cases of blindness in unnecessarily treated patients with drug-sensitive tuberculosis [9,10,11,12,13].

The study reported here aimed to determine [1] the proportion of failure/relapse in isoniazid resistant cases which is not captured by standard WHO monitoring [2] if bacterial factors can be used to predict those at highest risk of failure/relapse among those with isoniazid resistant tuberculosis and determine which patients would most benefit from modified regimens.

We assessed bacterial lineage, resistance mutation, isoniazid minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), and additional drug resistance in 239 patients with INH resistant tuberculosis identified among a cohort of 2091 new smear positive pulmonary TB patients. INH resistant TB included all isolates resistant to INH but susceptible to rifampicin (ie. Not MDR TB). Patients with INH resistant TB were followed for 2 years to determine the rate of relapse/failure which is not detected by standard WHO criteria for TB treatment outcome classification.

Methods

Ethics

The study was approved by the Institutional Research Board of Pham Ngoc Thach Hospital as the supervisory institution of the district TB Units (DTUs) in southern Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh City Health Services and the Oxford University Tropical Research Ethics Committee (Oxtrec 030–07). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to screening for INH susceptibility and, if resistant by MODS testing, a second written informed consent was obtained for enrolment into the INH study.

Recruitment

HIV uninfected adult (≥18 years of age) patients with new smear positive pulmonary tuberculosis presenting at participating DTUs in Ho Chi Minh City were invited to participate. From December 2008 four DTUs (districts 4, 6, Binh Thanh and Phu Nhuan) and the out-patient department at Pham Ngoc Thach Hospital recruited patients. In October 2009, a further 4 DTUs joined the study (district 1, 3, 8 and Tan Binh). District 3 was withdrawn from the study due to low recruitment (9 patients) in early 2010. A map of participating DTU sites is shown in Fig. 1. The study completed recruitment at all sites in June 2011.

If written informed consent was given for INH susceptibility screening, a sputum sample was sent to the microbiology laboratory at Pham Ngoc Thach hospital for MODS testing. Patients with isoniazid susceptible tuberculosis by MODS were then followed up according to routine DTU practice using standard WHO outcomes (smear at 2, 5 and 8 months) and no further testing was conducted for the study. All patients with isoniazid resistant TB by MODS screening were invited to participate in the INH study, with more detailed follow-up and testing. A second written informed consent was obtained for recruitment to the INH study.

Inclusion criteria for screening were a negative HIV test, written informed consent, a positive sputum smear, no previous TB treatment, ≥18 years of age, not pregnant or planning to receive DOTS outside the participating study centres. Patients were eligible for inclusion in the extended INH study if they met the above criteria, gave written informed consent to the extended INH study and were infected by a strain resistant to INH on MODS screening.

Treatment

Patients received treatment determined by the treating physician and usually in accordance with Vietnamese National TB Program (NTP) guidelines, which at the time of the study did not include any change in treatment for INH resistant TB unless the patient remained smear positive at 5 months. In accordance with NTP policy, patients smear positive at 5 months are classified as a treatment failure, tested for MDR TB and started on the retreatment regimen.

When the study commenced the standard regimen used in Vietnam was streptomycin (STR/S), rifampicin (RIF/R), INH (H) and pyrazinamide (PZA/Z) for the first two months (intensive phase) followed by 6 months with INH and EMB (continuation phase; 2SHRZ/6HE). In October 2009 the NTP replaced STR with EMB (2RHZE/6HE) as the first stage in a phased transition to the six month regimen (2RHZE/4HR) regimen. This enabled us to retrospectively compare failure and relapse rates between the two regimens (2SHRZ/6HE and 2RHZE/6HE) for patients with INH resistant TB but was not part of the original study design.

MODS was not accepted as a diagnostic assay for drug resistance within the NTP at the time of the study therefore patients with MDR TB diagnosed by MODS were referred to the NTP MDR treatment programme for confirmatory testing (using line-probe assay) and treatment according to standard NTP practice.

Follow-up

All patients in the screening and INH study were followed up according to WHO guidelines with sputum smear evaluation at 2, 5 and 8 months (treatment completion). A positive sputum smear at month 5 or later was classified as a retreatment case and further managed according to standard NTP practice. In addition, patients in the extended INH study were further evaluated for symptoms and sputum culture at month 8, 12, 18 and 24. A positive smear or culture at month 5 or later was classified as a failure/relapse case. MDR patient outcomes were not followed-up.

MODS testing

Drug susceptibility testing by direct MODS was performed according to the standard protocol for isoniazid and rifampicin [14]. Between December 2008 and 31 August 2010 the critical concentration for isoniazid was 0.4μg/ml. In 2010 the international recommended critical concentration changed to 0.1μg/ml following a meta-analysis by Minion et al. showing an increase in sensitivity compared to Lowenstein-Jensen (LJ) drug susceptibility testing (DST; 97.7% vs. 90.0%) [15] and we therefore adopted this change from 1st September 2010 until the end of the study (June 2011) [15].

Bactec MGIT

Phenotypic drug susceptibility testing for STR, INH, RIF and EMB was performed for all isolates at completion of the study using Bactec MGIT SIRE at the OUCRU laboratory. MGIT DST results were used as the gold standard for confirmation of INH resistance in further analysis.

Isoniazid MIC

INH antibiotic powder (Sigma, Germany) was used for determination of the INH MIC concentration at 0.2 μg/ml, 1 μg/ml, 2 μg/ml, 4 μg/ml, 8 μg/ml and 16 μg/ml using the 1% proportion method on LJ media.

Genotyping

DNA extraction was performed using the CTAB (cetyl trimethylammonium bromide)/chloroform method [16]. Isolate lineage was determined by Large Sequence Polymorphism (LSP) typing for RD105, RD239 and pks 15/1, as previously described [17]. Isolates were categorised into one of 3 major lineages; Euro-American, East-Asian or Indo-Oceanic. Any isolates failing to generate PCR products for LSP typing were typed and classified by spoligotyping using the standard methods [18] and the international spoligotyping database [19].

Statistical analysis

Treatment outcomes were categorized as favourable (cured and treatment completed) or unfavourable (death, treatment failed) according to WHO classifications. For INH resistant TB cases unfavourable outcomes included positive culture at month 5 or later.

INH-R TB was any Mtb resistant to isoniazid but susceptible to rifampicin (not MDR). Isolates in the INH-R cohort therefore included both INH monoresistant strains and strains resistant to INH and additionally resistant to streptomycin and/or ethambutol.

Multivariate logistic regression was used to identify variables associated with unfavourable outcome (death or treatment failure). A P-value of ≤0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analysis was done on Stata version 10 (Statacorp, USA).

Results

Treatment outcomes in screening patients

One patient Case Report Form (CRF) was irretrievable and therefore 2090 new pulmonary TB patients were evaluated by sputum smear microscopy after 5 and 8 months according to WHO guidelines followed by Vietnam NTP. The majority of patients (95.1%, n = 1987/2090) received the daily regimen according to Vietnamese NTP guidelines.

In total, 547 patients received 2SRHZ/6HE and 1440 patients received 2RHZE/6HE. The remaining 103 patients received alternative individualized regimens, such as 2SRHZ/RHZ/5HE, 2SRHZE/RHZE/5RHE, 3RHZE/5HE, 3RHZE/3RH, 2SRHZ/4RH and 2RHZE/4RH.

Patients treated at Pham Ngoc Thach hospital out-patient department were much more likely to receive individualized treatment regimens than those treated at the district TB units. Of those receiving individualized regimens, 95/103 (92.2%) were treated at Pham Ngoc Thach hospital out-patient department.

Overall, 1858 (88.9%) patients were cured and 6 (0.3%) patients were classified as ‘treatment completed’, therefore, 1864 patients (89.2%) were classified as having a favorable outcome. 16 patients died (0.8%), 121 (5.8%) failed treatment, 82 were lost to follow up (3.9%) and 7 (0.3%) were not evaluated. Therefore, a total of 226/2090 patients (10.8%) were classified as having an unfavourable outcome by WHO criteria.

Comparison of treatment outcomes of two standardized treatment regimens (2SRHZ/6HE and 2RHZE/6HE)

The crude odds ratio (OR) for unfavourable outcome was 0.94 [95% CI 0.65–1.35, P = 0.723] for patients receiving 2RHZE/6HE compared to those receiving 2SRHZ/6HE. Adjusting for resistance to INH or MDR by MGIT DST did not substantially change the OR: adjusted OR = 1.09 [95% CI 0.71–1.66], P = 0.703.

MODS screening

MODS cultures were positive for mycobacteria growth in 1804 cases. Of these, 1407 cases (67.3%) were susceptible to both RIF and INH, 324 cases (15.5%) were resistant to INH and susceptible to RIF, 5 cases (0.2%) were susceptible to INH and resistant to RIF, 68 cases (3.3%) were resistant to both INH and RIF (MDR). There were 202 cases (9.7%) which had a negative MODS culture and 85 cases (4.1%) that were indeterminate. The indeterminate category included isolates for which there was a negative result in the MODS control well and/or contamination of the control or sample well.

The change of INH critical concentration, from 0.4 μg/ml to 0.1 μg/ml, increased the percentage of isolates determined as INH resistant by MODS from 17.4% to 21.2%.

The percentage of isolates resistant to INH by MODS which were confirmed by MGIT DST increased significantly following the concentration change; 88.3% (n = 197/223) for 0.4 μg/ml and 98.4% (n = 120/122) for 0.1 μg/ml (P = 0.0007).

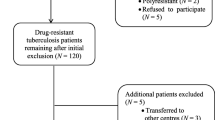

Overall, there were 392 cases with INH resistance by MODS (324 cases which were rifampicin susceptible and 68 cases which were MDR). 50 (12.6%) cases declined to participate in the INH study. Therefore, 274 cases of INH resistant TB were eligible to enter the INH study.

MGIT DST results

Further analysis of INH-resistant TB and MDR TB cases was based upon those with available MGIT DST as the gold standard (n = 1710, Table 1). Treatment outcome analysis included only those receiving standardised treatment regimens (n = 1623).

Risk factors for INH resistant TB and MDR TB

Demographic risk factors for INH-resistant and MDR TB are shown in Table 2. Analysis of the association between bacterial lineage and INH resistant TB or MDR TB is shown in Table 3.

Association between bacterial lineage and INH resistance mutations

Among 457 isolates resistant to INH by MGIT, Beijing lineage was significantly associated with katG315 mutation among INH resistant isolates, (OR = 2.10 [95% CI 1.41–3.13], P = < 0.0001), while Indo-Oceanic strains were significantly less likely to have a katG315 mutation (OR = 0.34 [95%CI 0.16–0.70], P = 0.003). No lineage showed an association with inhA − 15 promoter mutation. Indo -Oceanic strains were significantly more likely to be wild type, carrying neither a katG 315 nor an inhA − 15 mutation.

Treatment outcomes among INH resistant TB cases

239 patients in the extended INH study had confirmed INH resistant, RIF susceptible isolates by MGIT DST, received a standardised regimen and were therefore analysed for risk factors associated with unfavourable outcome. Using only routine programmatic sputum smear microscopy for assessment, 30/239 (12.6%) had an unfavourable outcome by WHO criteria. Thirty-nine patients were additionally detected with unfavourable outcomes during 2 year follow up, giving a total of 69/239 (28.9%) of INH resistant cases with unfavourable outcome by 2 years of follow-up.

Level of INH resistance (MIC)

LJ MIC results were available for 214/239 isolates. Among 239 isolates MIC for INH resistance were 0.2 μg/ml: 26, 1 μg/ml n = 81, 2 μg/ml n = 94, 4 μg/ml n = 8, 8 μg/ml n = 2 and 16 μg/ml n = 3.

MIC to INH was categorized into high (≥ 1 μg/ml) and low (< 1 μg/ml) for further analysis. Treatment outcomes (determined using smear and culture results) were evaluated by INH MIC level for 239 cases. There was no association between high MIC and unfavourable outcome (OR = 1.15 [95%CI 0.46–2.89], P = 0.764) or bacterial lineage (ANOVA, P = 0.289).

Bacterial factors associated with unfavourable treatment outcome among INH resistant cases

Analysis of bacterial factors associated with treatment failure in isoniazid resistant TB cases is shown in Table 4. Beijing lineage was the only factor significantly associated with unfavourable outcome during 2 years of follow-up. (adjusted OR = 3.16 [1.54–6.47], P = 0.002.

Discussion

Approximately one third (28.9%) of INH-resistant TB cases which were susceptible to rifampicin had failed or relapsed treatment within two years of starting treatment. Importantly, only 12.6% (n = 30/239) were classified as unfavourable outcome using WHO criteria of sputum smear evaluation at 5 and 8 months and so the majority of these cases would have been classified as ‘cured’ and received no further evaluation under standard practice. Overall, the cohort of 2090 patients had treatment outcomes within the WHO targets for programmatic delivery which masked an unacceptably high failure/relapse rate among INH-resistant TB cases. It is possible that this undetected high relapse/failure is at least partly responsible for the relatively slow decline in TB incidence in Vietnam despite a comprehensive NTP delivering DOTS and exceeding WHO targets for over ten years. The addition of culture to evaluation detected 46 (19.2%) failures by 8 months, and a total of 69 (28.9%) cases by two years of follow-up. The regimens used by the Vietnamese NTP at the time of this study were inadequate for INH resistant TB and this is demonstrated by the high rate of unfavourable outcomes in this cohort. The regimen has now been changed in line with revised WHO recommendations in areas of high INH resistance to 2HRZE/4HRE [8]. However, there is no existing evaluation of this regimen and the study reported here raises the concern that current routine programmatic outcome surveillance may be inadequate to detect failure/relapse in patients with INH resistant TB.

The East Asian/Beijing lineage was confirmed to be associated with MDR TB and INH resistant TB in Ho Chi Minh City [17, 20,21,22,23]. This lineage was also shown to be associated with treatment failure in INH resistant cases. The reasons for this association with treatment failure are not clear and require further research of the pharmacodynamics associated with bacterial lineage to unravel the complexities of bacterial persistence during treatment. Understanding of persistor mechanisms in M.tuberculosis are thought to be the key to shortened treatment regimens after the failure of three novel short regimens containing fluoroquinolones for drug sensitive TB in 2014 (OFLOTUB (NCT00216385), REMOX TB (NCT00864383) and RIFAQUIN (ISRCTN44153044) studies) [24,25,26].

Importantly the MIC to INH was not a risk factor for treatment failure, suggesting the current critical concentration 0.2 μg/ml for resistance is appropriate to define clinical resistance with current INH dosages. Similarly, despite reported associations of katG315 mutation with higher MIC than inhA -15 [27,28,29,30], the mutation conferring resistance could not be used to determine those at high risk of treatment failure/relapse.

This study has several limitations in addition to the outdated regimen assessed. Due to financial constraints, there was no culture follow-up in the drug-susceptible arm and therefore we were unable to compare the rates of unfavourable outcome detected by enhanced evaluation in INH susceptible TB cases. The 30-month report of the landmark clinical trial ‘study A’ conducted by the International Union against tuberculosis and Lung diseases (IUATLD) showed an unfavourable outcome rate of 10% for fully susceptibe TB at 30 months using the 8-month regimen [31].

We did not determine if isolates from culture positive cases post-treatment were due to relapse or reinfection, beyond broad LSP typing, which is not sufficiently discriminatory to confirm relapse. However, the contribution of reinfection is likely to be small as HCMC is not an intensive transmission area and the annual infection risk is low. There is a possibility that cases were reinfected from an untreated original household source, but this would not in any case be detected by genotyping as the genotypes would be identical to the original infection event.

Changes in both the treatment regimen and MODS INH critical concentration were made during the study. Although outcome did not vary by treatment regimen, the change in MODS concentration resulted in an increased proportion of INH resistance detected in the second part of the study and therefore recruited into the intensive follow-up arm. We used MGIT DST to confirm susceptibility in analysed INH-resistant cases.

Conclusions

Overall, these data confirm that the East Asian/Beijing lineage is associated with treatment failure in Vietnam. The data showing a third of those with INH resistant TB had unfavourable outcomes, the majority of which were not detected by standard WHO follow-up, suggest a rigorous evaluation of the new programmatic regimen (2HRZE/6HE) for areas with high INH-resistance is required. This should include symptom evaluation and mycobacterial culture where indicated up to 2 years to determine the true relapse and failure rate of the regimen in cases of INH resistance. Cost-effective solutions to early detection of INH resistant TB are a research priority, as are randomised controlled trials of alternative regimens for treatment of INH-resistant TB.

Abbreviations

- CRF:

-

Case report form

- CTAB:

-

Cetyl trimethylammonium bromide

- DTU:

-

District TB Unit

- EMB:

-

Ethambutol

- INH:

-

Isoniazid

- INH/H:

-

Isoniazid

- LJ:

-

Lowenstein-Jensen media

- LSP:

-

Large sequence polymorphism

- M. tuberculosis:

-

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- MDR TB:

-

multi-drug resistant TB

- MIC:

-

Minimum inhibitory concentration

- NTP:

-

National TB Programme

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PZA:

-

Pyrazinamide

- RIF/R:

-

Rifampicin

- STR/S:

-

Streptomycin

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

World Health Organisation Global Report. 2016. Geneva, Switzerland. WHO/HTM/TB/201613E. Available at: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/.

World Health Organisation. Anti-tuberculosis drug resistance in the World. Fourth global report. Report number WHO/HTM/TB/2008.39 http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2008/WHO_HTM_TB_2008.394_eng.pdf.

Lew W, Pai M, Oxlade O, Martin D, Menzies D. Initial drug resistance and tuberculosis treatment outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(2):123–34.

Menzies D, Benedetti A, Paydar A, Martin I, Royce S, Pai M, et al. Effect of duration and intermittency of rifampin on tuberculosis treatment outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2009;6(9):e1000146.

Menzies D, Benedetti A, Paydar A, Royce S, Madhukar P, Burman W, et al. Standardized treatment of active tuberculosis in patients with previous treatment and/or with mono-resistance to isoniazid: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2009;6(9):e1000150.

Gegia M, Winters N, Benedetti A, van Soolingen D, Menzies D. Treatment of isoniazid-resistant tuberculosis with first-line drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;

D'Ambrosio L, Migliori GB, Sotgiu G. Time to review treatment of isoniazid-resistant tuberculosis? Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;

World Health Organisation. Treatment of tuberculosis: guidelines for national programmes. 4th Edn. Report number: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/9789241547833/en/ accessed 11 august 2017.

Donald PR, Maher D, Maritz JS, Qazi S. Ethambutol dosage for the treatment of children: literature review and recommendations. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10(12):1318–30.

Ezer N, Benedetti A, Darvish-Zargar M, Menzies D. Incidence of ethambutol-related visual impairment during treatment of active tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17(4):447–55.

Leibold JE. The ocular toxicity of ethambutol and its relation to dose. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1966;135(2):904–9.

Chatterjee VK, Buchanan DR, Friedmann AI, Green M. Ocular toxicity following ethambutol in standard dosage. Br J Dis Chest. 1986;80(3):288–91.

Law S, Benedetti A, Oxlade O, Schwartzman K, Menzies D. Comparing cost-effectiveness of standardised tuberculosis treatments given varying drug resistance. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(2):566–81.

Moore DA, Evans CA, Gilman RH, Caviedes L, Coronel J, Vivar A, et al. Microscopic-observation drug-susceptibility assay for the diagnosis of TB. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1539–50.

Minion J, Leung E, Menzies D, Pai M. Microscopic-observation drug susceptibility and thin layer agar assays for the detection of drug resistant tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(10):688–98.

Honore-Bouakline S, Vincensini JP, Giacuzzo V, Lagrange PH, Herrmann JL. Rapid diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis by PCR: impact of sample preparation and DNA extraction. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(6):2323–9.

Caws M, Thwaites G, Dunstan S, Hawn TR, Lan NT, Thuong NT, et al. The influence of host and bacterial genotype on the development of disseminated disease with mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4(3):e1000034.

Isogen Life Science (An Ocimum Biosolutions Company). Spoligotyping - a PCR-based method to simultaneously detect and type Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex bacteria manual. http://www.springerlink.com/content/t78281g513k43397/#section=67734&page=1&locus=0.

Demay C, Liens B, Burguiere T, Hill V, Couvin D, Millet J, et al. SITVITWEB--a publicly available international multimarker database for studying mycobacterium tuberculosis genetic diversity and molecular epidemiology. Infect Genet Evol. 2012;12(4):755–66.

Nguyen VA, Banuls AL, Tran TH, Pham KL, Nguyen TS, Nguyen HV, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis lineages and anti-tuberculosis drug resistance in reference hospitals across Viet Nam. BMC Microbiol. 2016;16(1):167.

Buu TN, Huyen MN, Lan NT, Quy HT, Hen NV, Zignol M, et al. The Beijing genotype is associated with young age and multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in rural Vietnam. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;13(7):900–6.

Duong DA, Nguyen TH, Nguyen TN, Dai VH, Dang TM, Vo SK, et al. Beijing genotype of mycobacterium tuberculosis is significantly associated with high-level fluoroquinolone resistance in Vietnam. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53(11):4835–9.

Caws M, Thwaites G, Stepniewska K, Nguyen TN, Nguyen TH, Nguyen TP, et al. Beijing genotype of mycobacterium tuberculosis is significantly associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection and multidrug resistance in cases of tuberculous meningitis. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(11):3934–9.

Gillespie SH, Crook AM, McHugh TD, Mendel CM, Meredith SK, Murray SR, et al. Four-month moxifloxacin-based regimens for drug-sensitive tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(17):1577–87.

Jindani A, Harrison TS, Nunn AJ, Phillips PP, Churchyard GJ, Charalambous S, et al. High-dose rifapentine with moxifloxacin for pulmonary tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(17):1599–608.

Merle CS, Fielding K, Sow OB, Gninafon M, Lo MB, Mthiyane T, et al. A four-month gatifloxacin-containing regimen for treating tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(17):1588–98.

Abe C, Kobayashi I, Mitarai S, Wada M, Kawabe Y, Takashima T, et al. Biological and molecular characteristics of mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates with low-level resistance to isoniazid in Japan. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(7):2263–8.

Dalla Costa ER, Ribeiro MO, Silva MS, Arnold LS, Rostirolla DC, Cafrune PI, et al. Correlations of mutations in katG, oxyR-ahpC and inhA genes and in vitro susceptibility in mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical strains segregated by spoligotype families from tuberculosis prevalent countries in South America. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:39.

van Doorn HR, de Haas PE, Kremer K, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Borgdorff MW, van Soolingen D. Public health impact of isoniazid-resistant mycobacterium tuberculosis strains with a mutation at amino-acid position 315 of katG: a decade of experience in the Netherlands. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12(8):769–75.

van Soolingen D, de Haas PE, van Doorn HR, Kuijper E, Rinder H, Borgdorff MW. Mutations at amino acid position 315 of the katG gene are associated with high-level resistance to isoniazid, other drug resistance, and successful transmission of mycobacterium tuberculosis in the Netherlands. J Infect Dis. 2000;182(6):1788–90.

Nunn AJ, Jindani A, Enarson DA, Study Ai: Results at 30 months of a randomised trial of two 8-month regimens for the treatment of tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2011, 15(6):741–745.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and their families for participation in the study. We would also like to thanks all staff of the District tuberculosis Units, Pham Ngoc Thach Hospital and Oxford University Clinical Research Unit who contributed to the study.

Funding

This study was funded by the Wellcome trust fellowship 081814/Z/06/Z. grant awarded to PI: Maxine Caws.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available with identifying information removed from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PVKT co-ordinated the study and analysed the data and contributed to writing the manuscript. DTMH co-ordinated the laboratory testing and analysed the data. NTH co-ordinated all operational aspects of the study. JD designed the study and analysed the data. SD designed the study and analysed the data, contributed to writing the manuscript. NTQN co-ordinated all laboratory testing at OUCRU laboratory and analysed the data. VSK, NTT, NNL conducted laboratory testing and analysed the data. NHL, NHD, NHNL designed aspects of the study and co-ordinated management of the study. PTTL, NTH, DCD, NTKT, PTTL, NVH NVN, TN, HQM, NVT, NTH, DCD, NTKT recruited participants, contributed to study design collected and analysed data. JF contributed to design and management of the study. MC designed, analysed and wrote the manuscript for the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Institutional Research Board of Pham Ngoc Thach Hospital as the supervisory institution of the district TB Units (DTUs) in southern Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh City Health Services and the Oxford University Tropical Research Ethics Committee (Oxtrec 030–07). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to screening for INH susceptibility and, if resistant by MODS testing, a second written informed consent was obtained for enrolment into the INH study.

Consent for publication

not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Thai, P.V.K., Ha, D.T.M., Hanh, N.T. et al. Bacterial risk factors for treatment failure and relapse among patients with isoniazid resistant tuberculosis. BMC Infect Dis 18, 112 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3033-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3033-9