Abstract

Background

Infection by Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality. Colonization by S. aureus increases the risk of infection. Little is known about decolonization strategies for S. aureus beyond antibiotics, however probiotics represent a promising alternative. A randomized controlled trial was conducted to determine the efficacy of Lactobacillus rhamnosus (L. rhamnosus) HN001 in reducing carriage of S. aureus at multiple body sites.

Methods

One hundred thirteen subjects, positive for S. aureus carriage, were recruited from the William S. Middleton Memorial Medical Center, Madison, WI, USA, and randomized by initial site of colonization, either gastrointestinal (GI) or extra-GI, to 4-weeks of oral L. rhamnosus HN001 probiotic, or placebo. Nasal, oropharyngeal, and axillary/groin swabs were obtained, and serial blood and fecal samples were collected. Differences in prevalence of S. aureus carriage at the end of the 4-weeks of treatment were assessed.

Results

The probiotic and placebo groups were similar in age, gender, and health history at baseline. S. aureus colonization within the stool samples of the extra-GI group was 15% lower in the probiotic than placebo group at the endpoint of the trial. Those in the probiotic group compared to the placebo group had 73% reduced odds (OR 0.27, 95% CI 0.07–0.98) of methicillin-susceptible S. aureus presence, and 83% reduced odds (OR 0.17, 95% CI 0.04–0.73) of any S. aureus presence in the stool sample at endpoint.

Conclusion

Use of daily oral L. rhamnosus HN001 reduced odds of carriage of S. aureus in the GI tract, however it did not eradicate S. aureus from other body sites.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01321606. Registered March 21, 2011.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is a well-known cause of infection and can lead to serious adverse health outcomes including mortality. Asymptomatic colonization by S. aureus greatly increases risk of infection [1,2,3]. The nares are the primary site of S. aureus colonization, however, S. aureus has also been found to colonize the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, oropharynx, and axillae of many individuals [4,5,6]. Those colonized by methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) are at even greater risk of subsequent infection than those colonized with methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) [3, 7]. Thus reducing carriage of S. aureus is an important mitigating step in preventing infection.

Current treatment options for MRSA are limited to strong antibiotics that are accompanied by severe side effects and promote antibiotic resistance [8, 9]. Little is known about other S. aureus decolonization methods, however probiotics are emerging as a potentially low cost, well tolerated, and inexpensive alternative [10,11,12,13,14]. Probiotics are cultures of live bacteria species that normally reside in the human gut. They can help prevent infections by pathogens by outcompeting pathogenic bacteria for essential nutrients and mucosal binding sites, as well as enhancing immune function and promoting the production of mucosal and epithelial barriers [15]. Lactobacillus rhamnosus (L. rhamnosus) HN001, in particular has been shown to improve both innate and acquired immune function in multiple studies against a variety of bacterial infection threats [12, 13, 16,17,18,19]. It has been chosen for use in this study due to its immune effects and its safety and tolerability [20,21,22].

Given the paucity of data on the clinical use of probiotics to reduce S. aureus colonization [23], a randomized, double blind, phase II clinical trial was undertaken to evaluate the effect of probiotic use on S. aureus carriage. We hypothesized that the use of L. rhamnosus HN001, when compared to placebo, would decrease GI and extra-GI colonization by S. aureus, over a 4-week period.

Methods

Study design

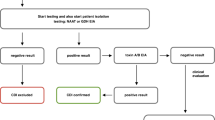

The full protocol for this study has been previously published [24]. Study procedures and written consent form were approved by the University of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board and the Veterans Affairs Research and Development Committee. A total of 113 subjects were recruited from the William S. Middleton Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Madison, WI, and screened for S. aureus colonization at several body sites (Week 0). At the first study visit (Day 0, Week 1) subjects were stratified by site of colonization at baseline, either GI or extra-GI, and randomized into the probiotic or placebo groups. Those whose oropharyngeal, or perirectal swab tested positive for S. aureus via real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay only at baseline were included in the GI group. Those who tested negative for GI sites, and had at least one positive result from nasal, axillary, or wound swabs were included in the extra-GI group. Stratification assignment was based solely on PCR results, not results of the culture assays that were also performed. The first blood and stool samples were also collected at this visit. Contact with subjects was made weekly to collect adherence and adverse events data, as well a stool sample at the end of Weeks 1, 2, and 3. At the second study visit (Week 4), patients were re-screened for S. aureus using nasal, oropharyngeal, axillary, and wound swabs. Final stool and blood samples were also collected at Week 4. Presence of S. aureus and L. rhamnosus in stool was assessed at each of these time points. Participant compliance and adverse events were self-reported weekly throughout the study. Non-compliance was defined as missing at least one medication dose during the duration of the study.

Enrollment criteria

Participants were eligible to enroll if they screened positive for S. aureus colonization, were at least 18 years of age, could take oral medication, and could consent to participation. A variety of exclusion criteria were used, including current MRSA decolonization or treatment regimens. A full list of inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in the protocol [24].

Intervention

The intervention consisted of once daily oral probiotic or placebo capsule administered for four weeks. The probiotic capsule contained 1 × 1010 colony forming units of L. rhamnosus HN001 and an inert filler. Placebo capsules were identical in appearance and taste, but contained only the inert fuller. Probiotic and placebo capsules were provided by DuPont Nutrition and Health, Madison, WI.

Microbiological analysis

Swabs and stool samples were analyzed for the presence of MSSA and MRSA using a real-time PCR assay, GeneXpert’s Xpert SA Nasal Complete kit (Cepheid, Sunnyvale CA), as well as traditional selective culture methods [25]. Cultures were grown using broth enrichment followed by standard microbiologic techniques including inoculation of selective media and identification of colony morphology [26]. Kirby Bauer Disk Diffusion testing was used to assess resistance to oxacillin [27, 28]. Stool samples were analyzed for the presence of L. rhamnosus HN001 using traditional culture methods followed by a strain specific in-house PCR.

Statistical analysis

To assess demographics and adverse events, frequency tables with Fisher’s exact test were used to account for small cell sizes. To make results of this trial more generalizable to a broader population, and more useful for practitioners, data was analyzed by intention to treat. To assess the effect of 4 weeks of treatment on colonization by S. aureus, comparing probiotic and placebo groups, the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test for differences across strata was used, stratifying by baseline carriage site (GI or extra-GI). All data analysis was conducted in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary NC).

Results

The study population was predominantly male, with an overall average age of 63.6 years old (Table 1). The study groups had similar medical histories, although the placebo group had a higher frequency of current liver disease than the probiotic group (Table 1). At baseline, 80% of patients were colonized at more than one sampling site. The large frequency of participants in the GI randomization group who were colonized at axillary/groin, nasal, and wound sites show that many participants were colonized at both GI and extra-GI sites (Fig. 1).

Percent frequency of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), methicillin susceptible S. aureus (MSSA), and total combined S. aureus (SA) colonization at endpoint and baseline of the probiotic and placebo groups within the gastrointestinal (GI) (a) and extra-GI (b) strata. Results shown are from both polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays, and culture assays. a Staphylococcus aureus Colonization at Baseline and Endpoint in GI Group. b Staphylococcus aureus Colonization at Baseline and Endpoint in Extra-GI Group

One participant was lost to follow-up and none withdrew from the study (Table 2). Rates of non-compliance were similar among the study groups, although they were slightly higher in the placebo group. Although the frequency of missing a single treatment dose was relatively high in both groups, only one participant missed more than 25% of study doses. The self-reported use of probiotic products other than the trial drug was similar between treatment groups. Detection by PCR found that no subject in any treatment arm was colonized at baseline with L. rhamnosus HN001. At week 4, 51.9% of the probiotic group, and 1.6% of the placebo group were colonized with L. rhamnosus HN001. There were no significant differences in adverse events between the probiotic and placebo groups (Table 2). Overall, bowel function was the most common adverse event experienced in both treatment groups. Those in the GI group experienced more muscle cramping than the extra-GI group.

The prevalence of MRSA, MSSA, and any S. aureus in stool samples collected at the end of weeks 1, 2, and 3 were similar between the placebo and probiotic groups each week (data not shown). Stool sample colonization by MSSA and total S. aureus (combined MSSA and MRSA) prevalence of those initially only colonized at extra-GI sites was lower in the probiotic than placebo group by more than 15%, (Fig. 1). It is also notable that there was an approximately 30% reduction in nasal colonization by MSSA in the extra-GI placebo group between baseline and week 4 (Fig. 1). The odds ratio, adjusted for original colonization site, estimates that those in the probiotic group had 73% lower odds of MSSA presence, and 83% lower odds of any S. aureus presence in the stool sample at endpoint, as those in the placebo group (Fig. 2). No other sampling sites showed a significant difference in endpoint colonization between the probiotic and placebo groups (Fig. 2). When sampling sites were pooled and analyzed in categories of GI or extra-GI, there were no significant differences between probiotic and placebo groups (Table 3).

Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel odds ratios of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), methicillin susceptible S. aureus (MSSA), and total combined S. aureus (SA) colonization at different body sites, stratified by initial colonization site, either gastrointestinal (GI), or extra-GI, comparing the probiotic group to the placebo group

Because the original stratification of treatment was done using only PCR colonization results, some participants were stratified to the extra-GI group, but had positive cultures at GI sites. We undertook a sensitivity analysis in which we re-categorized these subjects by initial colonization site based on all swab and stool samples analyzed by both culture and PCR (instead of just by PCR). Twenty participants (10 placebo, 10 probiotic) originally included in the extra-GI randomization strata were moved to the GI strata in this analysis. While effect sizes of the odds ratios were similar to the original analysis, there was no statistical significance (Additional file 1).

Discussion

S. aureus infections are a serious health risk with limited treatment options, and those who are colonized by S. aureus are at much higher risk of symptomatic infection. In this study, we observed that administration of L. rhamnosus HN001 over a four-week period reduced the odds of colonization in the stool sample, especially for those who were originally colonized outside of the GI tract. Probiotic treatment did not, however, reduce odds of colonization at other body sites. While the probiotic was not successful at eradicating S. aureus colonization at all body sites, it was associated with lower odds of colonization in the GI tract, especially for those who were stratified to the extra-GI group.

The surprising result of the reduction in nasal MSSA colonization in the extra-GI placebo group is likely explained by the natural history of S. aureus colonization. S. aureus is known to colonize intermittently and its presence is dependent on a number of factors including environmental exposures and other colonizing bacteria, to name a few [29,30,31]. Our study did not collect daily exposure data on participants to control for these external factors, which is why the placebo-controlled arm of the study was so important.

L. rhamnosus HN001 is thought to work in multiple ways. The primary potential mechanism is competitive inhibition, whereby colonizing the GI tract with healthy commensal microbes prevents the colonization of pathogens by out-competing them for vital resources [32]. This is likely the mechanism that led to differences in stool colonization between probiotic and placebo groups. A second potential mechanism is that L. rhamnosus HN001 has previously been shown to stimulate systemic immune function [12, 13, 18], making the host immune system more capable of eliminating S. aureus colonization at sites throughout the body. Based on the null results from body sites examined beyond the stool sample, it is likely that the L. rhamnosus HN001 used in this study population did not produce enough of a systemic immune response to affect S. aureus colonization at sites outside the gut. Further testing of phagocytic activity in the blood samples is currently being conducted to evaluate this hypothesis.

Our results differ from those of a study conducted in 2003 by Glück and Gebbers [14], which found that ingestion of L. rhamnosus GG, significantly reduced the occurrence of nasal carriage of potentially pathogenic bacteria. However, this discrepancy is likely due to the different strain of probiotic used in the intervention, a different delivery matrix used (yogurt/fermented milk product versus capsule), or inclusion of different Staphylococcus species in the outcome. There is a paucity of data on in vivo use of probiotics as a decolonization strategy for S. aureus, and more research is needed in this area.

This trial contributes critical knowledge to the literature about the efficacy of probiotics to reduce S. aureus colonization, however, it does include some limitations. Participants of this trial were drawn from the Veterans Affairs hospital system in Madison, WI. This system predominantly serves older men, thus the majority of the study sample were older men. Therefore, this sample may not be broadly generalizable to other populations.

The seven inpatients in this study were at increased risk of re-exposure to S. aureus during their hospital stay. It is possible these patients were cleared of their original S. aureus carriage, and re-colonized during the course of the trial. While stool samples were taken during the course of the intervention, no swabs of sample sites were taken between the baseline and endpoints of the trial. Thus, we cannot determine if any subjects were de-colonized and subsequently re-colonized at any of the swabbed sites between sampling. If this were the case for any of our sample, it would bias our results toward the null. The number of inpatients in each treatment group were not statistically different, therefore adjustment for ambulatory status in the analysis was not warranted. In the future, strain typing of stored isolates from stool samples can reduce this possibility of bias.

Considering that the only significant difference in health history between the treatment groups at baseline was prevalence of liver disease, we do not believe underlying health conditions affect the interpretation of trial results. Likewise, although overall non-compliance was around 30% in both treatment groups, all but one participant missed less than a quarter of the trial doses. Non-compliance with the assigned treatment would bias our results toward the null, and given the low number of doses missed by the majority of non-compliant participants, we do not believe this strongly biases the study findings. Use of other probiotics during the study may be more troublesome. Use of all possible probiotic supplements, including yogurts, capsules, etc., were considered as other probiotic use, however, we did not verify that reported probiotic supplements actually contained probiotics. The reported use of outside probiotics by approximately 1/3 of the placebo group could bias these findings toward the null by making the treatment groups more similar than otherwise expected. Future studies should carefully monitor the use of probiotics outside of study treatment.

Conclusion

The results of our study support the use of this probiotic strain for gut decolonization by S. aureus, including MRSA. Further studies are needed to replicate the findings of this study and compare probiotics with other available agents used for decolonization such as antibiotics. Other directions for future research include examining the effect of alternative probiotic bacterial strains on S. aureus nasal colonization.

Abbreviations

- GI:

-

Gastrointestinal

- L. rhamnosus :

-

Lactobacillus rhamnosus

- MRSA:

-

Methicillin-resistant S. aureus

- MSSA:

-

Methicillin-susceptible S. aureus

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- S. aureus :

-

Staphylococcus aureus

References

Jenkins A, Diep BA, Mai TT, Vo NH, Warrener P, Suzich J, et al. Differential expression and roles of Staphylococcus aureus virulence determinants during colonization and disease. MBio. 2015;6(1):e02272–14. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4337569/. [cited 2017 Feb 6]

Roghmann M-C, Siddiqui A, Plaisance K, Standiford H. MRSA colonization and the risk of MRSA bacteraemia in hospitalized patients with chronic ulcers. J Hosp Infect. 2001;47:98–103.

Safdar N, Bradley EA. The risk of infection after nasal colonization with staphylococcus aureus. Am J Med. 2008;121:310–5.

Eveillard M, de Lassence A, Lancien E, Barnaud G, Ricard J, Joly-Guillou M. Evaluation of a strategy of screening multiple anatomical sites for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus at admission to a teaching hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2006;27:181–4.

El-Bouri K, El-Bouri W. Screening cultures for detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a population at high risk for MRSA colonisation: identification of optimal combinations of anatomical sites. Libyan J Med. 2013;8:1–5. Available from: http://www.libyanjournalofmedicine.net/index.php/ljm/article/view/22755. [cited 2016 May 26]

Matheson A, Christie P, Stari T, Kavanagh K, Gould IM, Masterton R, et al. Nasal swab screening for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus—how well does it perform? A cross-sectional study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33:803–8.

Davis KA, Stewart JJ, Crouch HK, Florez CE, Hospenthal DR. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) nares colonization at hospital admission and its effect on subsequent MRSA infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:776–82.

Levy SB, Marshall B. Antibacterial resistance worldwide: causes, challenges and responses. Nat Med. 2004;10:S122–9.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2013.

Pamer EG. Resurrecting the intestinal microbiota to combat antibiotic-resistant pathogens. Science. 2016;352:535–8.

Cunningham-Rundles S, Ahrné S, Bengmark S, Johann-Liang R, Marshall F, Metakis L, et al. Probiotics and immune response. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:S22–5.

Gill HS, Rutherfurd KJ. Immune enhancement conferred by oral delivery of lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 in different milk-based substrates. J Dairy Res. 2001;68:611–6.

Gill HS, Rutherfurd KJ. Probiotic supplementation to enhance natural immunity in the elderly: effects of a newly characterized immunostimulatory strain lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 (DR20™) on leucocyte phagocytosis. Nutr Res. 2001;21:183–9.

Glück U, Gebbers J-O. Ingested probiotics reduce nasal colonization with pathogenic bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and β-hemolytic streptococci). Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:517–20.

Ulluwishewa D, Anderson RC, McNabb WC, Moughan PJ, Wells JM, Roy NC. Regulation of tight junction permeability by intestinal bacteria and dietary components. J Nutr. 2011;141:769–76.

Shu Q, Gill HS. Immune protection mediated by the probiotic lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 (DR20™) against Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection in mice. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2002;34:59–64.

Gill HS, Rutherfurd KJ, Prasad J, Gopal PK. Enhancement of natural and acquired immunity by lactobacillus rhamnosus (HN001), lactobacillus acidophilus (HN017) and Bifidobacterium lactis (HN019). Br J Nutr. 2000;83:167–76.

Cross ML, Mortensen RR, Kudsk J, Gill HS. Dietary intake of lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 enhances production of both Th1 and Th2 cytokines in antigen-primed mice. Med Microbiol Immunol (Berl). 2002;191:49–53.

Sheih Y-H, Chiang B-L, Wang L-H, Liao C-K, Gill HS. Systemic immunity-enhancing effects in healthy subjects following dietary consumption of the lactic acid bacterium lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001. J Am Coll Nutr. 2001;20:149–56.

Shu Q, Zhou JS, Rutherfurd KJ, Birtles MJ, Prasad J, Gopal PK, et al. Probiotic lactic acid bacteria (lactobacillus acidophilus HN017, lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 and Bifidobacterium lactis HN019) have no adverse effects on the health of mice. Int Dairy J. 1999;9:831–6.

Zhou JS, Gopal PK, Gill HS. Potential probiotic lactic acid bacteria lactobacillus rhamnosus (HN001), lactobacillus acidophilus (HN017) and Bifidobacterium lactis (HN019) do not degrade gastric mucin in vitro. Int J Food Microbiol. 2001;63:81–90.

Zhou JS, Shu Q, Rutherfurd KJ, Prasad J, Birtles MJ, Gopal PK, et al. Safety assessment of potential probiotic lactic acid bacterial strains lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001, Lb. acidophilus HN017, and Bifidobacterium lactis HN019 in BALB/c mice. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2000;56:87–96.

Sikorska H, Smoragiewicz W. Role of probiotics in the prevention and treatment of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2013;42:475–81.

Eggers S, Barker A, Valentine S, Hess T, Duster M, Safdar N. Impact of probiotics for reducing infections in veterans (IMPROVE): study protocol for a double-blind, randomized controlled trial to reduce carriage of Staphylococcus aureus. Contemp Clin Trials. 2016;52:39–45.

Safdar N, Narans L, Gordon B, Maki DG. Comparison of culture screening methods for detection of nasal carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a prospective study comparing 32 methods. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:3163–6.

Wormser GP, Stratton C. Manual of clinical microbiology, 9th edition. In: Murray PR, Baron EJ, Jorgensen JJ, Landry ML, Pfaller MA, editors. . 9th ed. Washington (DC): American Society of Microbiology; 2007.

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 26th informational supplement. Wayne: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2016. p. Report No.: M100–S26.

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard. 10th ed. Wayne: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2006. p. Report No.: CLSI M07–A10.

Shenoy ES, Paras ML, Noubary F, Walensky RP, Hooper DC. Natural history of colonization with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant enterococcus (VRE): a systematic review. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:177.

Syed AK, Ghosh S, Love NG, Boles BR. Triclosan promotes Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization. MBio. 2014;5:e01015.

Yan M, Pamp SJ, Fukuyama J, Hwang PH, Cho DY, Holmes S, et al. Nasal microenvironments and interspecific interactions influence nasal microbiota complexity and S. Aureus carriage. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14:631–40.

Gueimonde M, Jalonen L, He F, Hiramatsu M, Salminen S. Adhesion and competitive inhibition and displacement of human enteropathogens by selected lactobacilli. Food Res Int. 2006;39:467–71.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all study staff and participants, without whom this work would not have been possible. Thanks to DuPont Nutrition and Health for supplying the probiotics and PCR protocols for L. rhamnosus used in this trial.

Funding

This work was supported by the Biomedical Laboratory Research & Development Service of the VA Office of Research and Development [grant number I01BX007080]; and National Institute of Health [grant numbers UL1TR000427 and TL1TR000429, administered by the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Institute for Clinical and Translational Research] to AB. The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs. These funding sources had no role in the design, implementation, data analysis, interpretation of data, or manuscript writing for this study.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset created and analyzed during this study are available from NS upon reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SE performed data analysis, contributed to data interpretation, and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. AB contributed to interpretation of the data and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. SV and MD made contributions to design and acquisition of data and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. TH made contributions to study design, assisted with data analysis and interpretation, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. NS made major contributions to study design, acquisition and interpretation of data, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Institutional Review Board (#2011–0063). All participants completed written informed consent prior to enrollment into the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

SE’s spouse is employed by DuPont Nutrition and Health, who supplied the trial treatments, however this association had no influence on the conduct or outcome of this trial. All other authors have no competing interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

ST1. Sensitivity analysis results: frequencies of MRSA, MSSA, and Total SA colonization at the endpoint of the trial at each body site, stratified by re-assigned GI or extra-GI colonization group based on PCR and culture screening results at baseline, and probiotic or placebo treatment group. (DOCX 110 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Eggers, S., Barker, A.K., Valentine, S. et al. Effect of Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 on carriage of Staphylococcus aureus: results of the impact of probiotics for reducing infections in veterans (IMPROVE) study. BMC Infect Dis 18, 129 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3028-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3028-6