Abstract

Background

The early identification of patients at risk of dying from community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is critical for their treatment and for defining hospital resource consumption. Mid-regional pro-adrenomedullin (MR-proADM) has been extensively investigated for its prognostic value in CAP. However, the results are conflicting. The purpose of the present meta-analysis was to explore the diagnostic accuracy of MR-proADM for predicting mortality in patients suffering from CAP, particularly emergency department (ED) patients.

Method

We systematically searched the PubMed, Embase, Web of Knowledge and Cochrane databases. Studies were included if a 2 × 2 contingency table could be constructed based on both the MR-proADM level and the complications or mortality of patients diagnosed with CAP. The prognostic accuracy of MR-proADM in CAP was assessed using the bivariate meta-analysis model. We used the Q-test and I 2 index to evaluate heterogeneity.

Results

MR-proADM displayed moderate diagnostic accuracy for predicting complications in CAP, with an overall area under the SROC curve (AUC) of 0.74 (95 % CI: 0.70–0.78). Eight studies with a total of 4119 patients in the emergency department (ED) were included. An elevated MR-proADM level was associated with increased risk of death from CAP (RR 6.16, 95 % CI 4.71–8.06); the I 2 value was 0.0 %, and a fixed-effects model was used to pool RR. The pooled sensitivity and specificity were 0.74 (95 % CI: 0.67–0.79) and 0.73 (95 % CI: 0.70–0.77), respectively. The positive likelihood ratio (PLR) and negative likelihood ratio (NLR) were 2.8 (95 % CI, 2.3–3.3) and 0.36 (95 % CI, 0.29–0.45), respectively. In addition, the diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) was 8 (95 % CI, 5–11), and the overall area under the SROC curve was 0.76 (95 % CI, 0.72–0.80).

Conclusions

Our study has demonstrated that MR-proADM is predictive of increased complications and higher mortality rates in patients suffering from CAP. Future studies are warranted to determine the prognostic accuracy of MR-proADM in conjunction with severity scores or other biomarkers and to determine an optimal cut-off level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Lung infections are the most frequent type of infection worldwide. Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is a disease with a very wide range of possible outcomes. A considerable proportion of patients can be treated as outpatients. Additionally, CAP may serve as a sepsis precursor and is more likely to result in death in critically ill patients [1]. Risk stratification is crucial to CAP patient management in the emergency department (ED) to select the most appropriate care setting, including outpatient treatment, admission to a hospital ward (HW) or admission to an intensive care unit (ICU). Thus, clinical studies are currently focusing on searching for the most appropriate prognostic factors and risk stratification tools in respiratory medicine.

Several risk scores (PSI, CURB65) have been developed for assessing the severity of CAP and predicting mortality [2, 3]. However, none are ideal for clinical use. Some scores are too complicated to use in daily practice, and some are not exempt from false-positive and false-negative results. Blood biomarkers (for example, C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1, and interleukin-1 beta) may improve the diagnostic accuracy of those scores and may provide additional information regarding the prognosis of patients suffering from CAP [4–7].

Human adrenomedullin (ADM), a 52-amino acid peptide, is a member of the calcitonin peptide family [8]. It is widely expressed and intensively synthesized in organisms suffering from severe infection. It is one of the most potent vasodilating agents and functions in immune modulation, antibiosis and metabolic regulation [9–12]. ADM immediately binds to receptors near the site of its production and has a short half-life [13]. The more stable mid-regional (MR) fragment of the ADM precursor is directly reflective of the level of the rapidly degraded active ADM peptide [14]. Clinically, MR-proADM is commonly used due to its better technical viability than that of ADM. In addition, its level may be indicative of the severity of infection. Increasing evidence has shown that MR-proADM is a superior biomarker compared with others (such as procalcitonin and soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1) for prognostic purposes in sepsis [15, 16], as well as CAP [17]. Thus, we performed this meta-analysis to systematically and quantitatively analyze all available publications that have assessed the prognostic accuracy of the MR-proADM level in CAP patients to draw a firm conclusion from these studies.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

Two investigators, Liu D and Xie LX, independently performed the search and assessed the studies. Any disagreement was resolved by consulting with a third investigator (Xie LX). We searched PubMed, Embase, Web of Knowledge and the Cochrane Library. The search terms were as follows: (adrenomedullin or ADM or proADM or "midregional proadrenomedullin" or MR-proADM or proadrenomedullin) and ("respiratory tract infection" or "respiratory infection" or "pneumonia" or "community-acquired pneumonia" or CAP). An example of the search details is presented in Appendix 1. We included articles written in English and Spanish, and no publication date restrictions were applied in the search.

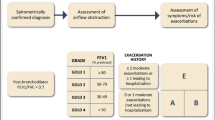

Eligible studies had to have a well-defined reference standard for patients diagnosed with CAP. They had to collect data on MR-proADM levels in adult patients (>18 years old) with mortality or complications from CAP and provide sufficient data for construction of a 2 × 2 contingency table based on the results. Low risk was defined by PSI score classes I to III and CURB-65 score class 1, and high risk was defined by PSI score classes IV–V and CURB-65 score classes 2–5, according to previous criteria [18, 19]. For studies providing multiple MR-proADM cut-off levels for prognostic accuracy, the data presenting the maximum overall accuracy were selected. All published studies had obtained ethics approval and consent for publication of these data. Ethics approval was not sought as this systematic review which synthesized the public data.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two investigators, Liu D and Xie LX, independently extracted data and assessed the quality of the included studies. Any conflicts were resolved by consulting with a third investigator. The following data were extracted from the original studies: the name of the first author, publication year, country of origin, study design, clinical setting, assay manufacturer, sample size, endpoints, percentage of high-risk patients according to the PSI score or CURB-65 score, prevalence of mortality or complications, and MR-proADM cut-off level, and the true positive (TP), false positive (FP), false negative (FN), true negative (TN), sensitivity (SEN) and specificity (SPE) of the data. We contacted the corresponding authors if the data were not presented or needed clarification. We evaluated the quality of the included studies according to the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2) checklist [20] for diagnostic studies. Risk of bias was judged as “low”, “high” or “unclear”.

Statistical analysis

We chose the MIDAS module of STATA software, version 12.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX) and Meta-Disc 1.4 (XI Cochrane Colloquium, Barcelona, Spain) to perform statistical analyses. TP, FP, FN, and TN were tabulated based on the MR-proADM levels and all-cause mortality in CAP. We used relative risk (RR) to access the predictive value of MR-proADM based on DerSimonian and Laird’s method [21]. The Q-test and I 2 index were conducted to assess inter-study heterogeneity [22, 23]. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Values of 25, 50 and 75 % for the I 2 test represented low, medium and high heterogeneity, respectively [24]. If the I 2 values were less than 50 %, then the fixed-effects model was used; otherwise, the random-effects model was used to analyze the data.

The presence of a threshold effect on the prognostic accuracy of MR-proADM in CAP was evaluated with the Spearman correlation coefficient between the logits of sensitivity and specificity. If no threshold effect existed, then a bivariate random-effects regression model [25] was used to calculate the pooled sensitivity (SEN), specificity (SPE), diagnostic odds ratio (DOR), positive likelihood ratio (PLR), and negative likelihood ratio (NLR). If a threshold effect existed, then we only constructed a summary receiver operator characteristic (SROC) curve by plotting the individual and summary values of sensitivity and specificity to access overall diagnostic accuracy [26].

Univariate meta-regression and subgroup analyses were performed to examine the sources of potential heterogeneity in SEN and SPE. The covariates included the following variables: Consecutive (if studies recruited patients consecutively), Prevalence (prevalence of mortality < 10 % or ≥ 10 %), Sample size (sample size < 500 or ≥ 500), and Blinded (if clinicians influenced patients’ outcomes without knowledge of the MR-proADM levels).

Results

Our database search resulted in the retrieval of 775 articles, of which 746 were eliminated for various reasons related to the title and abstract, leaving 19 studies that were scrutinized by full-text reviews. Among these 19 studies, 1 study measured the level of ADM, 3 did not provide sufficient information to construct a 2 × 2 table, and 3 included ineligible patients (not CAP patients). Ultimately, 12 studies [27–38] fulfilled our eligibility criteria and were included (Fig. 1). The characteristics of the included studies are listed in Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

The included studies were published from 2006 to 2014. Ten studies [27–33, 35, 36, 38] were published in English, and two [34, 37] were in Spanish. All of the studies were prospective cohorts, and three [27, 31, 38] were multiple-center trials. Three of the studies [27, 33, 38] selected patients from a randomized clinical trial. All of the studies were conducted in Europe. The mean patient ages varied from 59 to 73 years, and the proportion of men ranged from 31.6 to 74. The prevalence of mortality ranged from 2.5 to 35. The prevalence of complications ranged from 5.6 to 64. The studies were performed in EDs [27–34, 37], ICUs [35, 38] and HWs [36]. The primary endpoint was development of complications [27, 28, 36–38], and the secondary endpoint was mortality [27–35]. In all of the studies, MR-proADM was detected by an automated immunofluorescence assay (BRAHMS MR-proADM KRYPTOR, BRAHMS GmbH, Hennigsdorf, Germany) [39].

Study quality and publication bias

The quality of the included studies is shown in Appendix 2. Deek’s Funnel Plot is presented in Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Data synthesis and meta-analysis

Analysis of the association of MR-proADM with development of complications

Five studies [27, 28, 36–38] with a total of 2361 patients were included in this group. However, a significant threshold effect was observed (Spearman correlation coefficient = 0.900; P = 0.037). Therefore, we only calculated the overall area under the SROC curve (AUC), which was 0.74 (95 % CI: 0.70–0.78) (Additional file 2: Figure S2.).

Analysis of the effect of MR-proADM on mortality

Nine studies [27–39] with a total of 4119 patients were included in this group. All of them showed that an elevated MR-proADM level was associated with higher risk of death from CAP. Because the heterogeneity between studies was 21.7 %, the fixed-effects model was used. The pooled RR was 5.83 (95 % CI 4.53–7.52) (Additional file 3: Figure S3.).

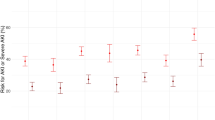

One study [35] analyzed CAP patients in an ICU with a relatively high mortality rate. We found that this study had a more heterogeneous population compared with the other included studies. Thus, we excluded it and focused on the association of the MR-proADM level with short-term mortality in ED patients. Because the heterogeneity between studies was 0.0 %, a fixed-effects model was used to pool RR. For the ED patients, an elevated MR-proADM level was associated with an increased risk of short-term mortality (RR 6.16, 95 % CI 4.71–8.06) (Fig. 2).

We observed no statistically significant differences in threshold effects (Spearman correlation coefficient = 0.252; P = 0.548). Thus, the bivariate random-effects regression model was used to perform meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy to evaluate the overall sensitivity and specificity of MR-proADM for predicting mortality in CAP. The pooled sensitivity and specificity were 0.74 (95 % CI: 0.67–0.79) and 0.73 (95 % CI: 0.70–0.77), respectively (Fig. 3). The positive likelihood ratio (PLR) and negative likelihood ratio (NLR) were 2.8 (95 % CI, 2.3–3.3) and 0.36 (95 % CI, 0.29–0.45), respectively. The diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) was 8 (95 % CI, 5–11). The overall area under the SROC curve was 0.76 (95 % CI, 0.72–0.80) (Fig. 4), indicating moderate diagnostic accuracy. The mean cut-off MR-proADM level for predicting mortality in CAP was 1.416 ng/ml (IQR 0.959–1.85).

The overall I 2 value for the bivariate model was 0.0 % (95 % CI 0–100). The I 2 values for the pooled SEN and SPE were 0.00 % (95 % CI 0–100) and 81.31 % (95 % CI 69.13–93.48), respectively. Univariate meta-regression and subgroup analyses were performed to examine the sources of potential heterogeneity in SEN and SPE. The covariates included the following: Consecutive (if studies recruited patients consecutively), Prevalence (prevalence < 10 % or ≥ 10 %), Sample size (sample size < 500 or ≥ 500), and Blinded (if clinicians influenced patients’ outcomes without knowledge of the MR-proADM levels). The results showed that sample size was significantly associated with the heterogeneity of SEN, whereas the covariates Consecutive, Sample size, Prevalence and Blinded were significantly associated with the heterogeneity of SPE (Fig. 5). We performed subgroup analysis according to the different prevalence rates of mortality. Three of the studies [29, 32, 34] had a prevalence of over 10 %, with pooled sensitivity and specificity values of 0.78 (95 % CI: 0.67–0.89) and 0.78 (95 % CI: 0.72–0.84), respectively. In addition, five of the studies [27, 28, 30, 31, 33] had a prevalence of less than 10 %, with pooled sensitivity and specificity values of 0.72 (95 % CI: 0.66–0.78) and 0.72 (95 % CI: 0.68–0.75), respectively.

Discussion

In this meta-analysis, we restricted our scope to patients in the ED. We aimed to help clinicians to select the most appropriate care setting for CAP patients in the ED, including outpatient treatment, admission to a hospital ward, or admission to an intensive care unit. We first found that an elevated MR-proADM level was significantly associated with an increased risk of mortality in the ED patients with CAP. Clinical scores are recommended for clinical decision-making in the evaluation of CAP patients [40]. However, many studies have found that these clinical scores are not exempt from false-positive and false-negative results and are not ideal for clinical use. Many patients are misclassified into the high-risk classes IV and V according to the PSI score [41]. Meta-analysis [42] has shown that the CURB-65 score has a sensitivity of only 0.62 for predicting mortality in CAP. Marrie et al. [43] have demonstrated that a considerable number of CAP patients identified as high risk based on a PSI level of IV or V can be treated safely as outpatients, with subsequent low mortality. Our study evaluated the prognostic value of ProADM in CAP and revealed that the positive likelihood ratio (PLR) and negative likelihood ratio (NLR) were 2.8 (95 % CI, 2.3–3.3) and 0.36 (95 % CI, 0.29–0.45), respectively. These results indicate that MR-proADM is more clinically useful than any of the risk scores previously identified in another meta-analysis [42].

Because the included studies used different cut-off values, simply pooling data from each trial may have contributed to bias in the meta-analysis results. Thus, in our meta-analysis, we conducted statistical analysis to ensure the eligibility and reliability of our results before tabulating the data from each trial. We used Meta-Disc to evaluate the Spearman correlation coefficient. We calculated the RR, SEN, SPE, DOR, PLR, and NLR for each trial based on the premise that there were no significant differences in the threshold effects (P > 0.05), indicating that the heterogeneity attributed to the use of different cut-off values was acceptable. Thus, our results are more accurate than those of other diagnostic and prognostic meta-analyses.

Our study has several limitations. First, all of the studies included in our meta-analysis were conducted in Europe. Thus, our results are restricted to Europeans. Second, Deek’s funnel plot revealed the existence of potential publication bias. Third, we could not determine the optimized cut-off value because we failed to obtain the raw data from each original article to construct an ROC curve. We attempted to contact the corresponding authors to obtain the data, but it was difficult to acquire the ProADM levels of the patients in each trial. Albrich et al. [27] have examined the ProADM level and CURB65 score combined and have found that the risk of unfavorable outcome is low for patients with a CURB65 score of 0–1 and a ProADM level of ≤0.75 nmol/l, intermediate for patients with a CURB65 score of 2 and a ProADM level of ≤1.5 nmol/l or a CURB class of 0–1 and a ProADM level of between 0.75 and 1.5 nmol/L, and high for all other patients. Another study [44] has also focused on the prognosis of CAP patients using these ProADM cut-off levels. All in all, further studies are warranted to define the proper cut-off level for clinical use.

CAP is a complex pathophysiological process rather than a specific syndrome. Thus far, no ideal biomarker or clinical score has shown sufficient sensitivity and specificity for clinical utility to predict death in CAP. Clinicians need to comprehensively evaluate individual conditions. Future research should highlight incorporation of MR-proADM into an overall assessment of CAP prognosis in combination with other clinical indexes instead of focusing on adopting a biomarker-based or score-based approach to predicting mortality. Additionally, future studies should be conducted specifically on patients with different conditions (e.g., different CAP severities or different types of infection) to help optimize therapeutic decisions for individual patients.

Conclusions

Our study has demonstrated that MR-proADM is predictive of increased complications and a higher mortality rate in patients suffering from CAP. Further studies are warranted to clarify the prognostic accuracy of MR-proADM in conjunction with severity scores or other biomarkers and to determine an optimal cut-off level.

Abbreviations

CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; CI, confidence interval; CR, consecutively recruitment; DOR, diagnostic odds ratio; ED, emergency department; FN, false negative; FP, false positive; LR, likelihood ratio; MPR, multiple-centre prospectively recruitment; MRCT, multiple-centre random control trail; MR-proADM, midregional proadrenomedullin; NLR, negative likelihood ratio; PLR, positive likelihood ratio; PR, prospectively recruitment; QUADAS, quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies; RCT, random control trail; RR, risk ratio; SEN, sensitivity; SPE, specificity; SROC, summary receiver operator characteristic; TN, true negative; TP, true positive.

References

Mizgerd JP. Acute lower respiratory tract infection. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(7):716–27.

Kolditz M, Ewig S, Höffken G. Management-based risk prediction in community-acquired pneumonia by scores and biomarkers. Eur Respir J. 2013;41:974–84.

Ewig S, Bauer T, Richter K, Szenscenyi J, Heller G, Strauss R, Welte T. Prediction of in-hospital death from community-acquired pneumonia by varying CRB-age groups. Eur Respir J. 2013;41:917–22.

Hohenthal U, Hurme S, Helenius H, Heiro M, Meurman O, Nikoskelainen J, Kotilainen P. Utility of C-reactive protein in assessing the disease severity and complications of community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15(11):1026–32.

van Vugt SF, Broekhuizen BD, Lammens C, Zuithoff NP, de Jong PA, Coenen S, Ieven M, Butler CC, Goossens H, Little P, Verheij TJ. Use of serum C reactive protein and procalcitonin concentrations in addition to symptoms and signs to predict pneumonia in patients presenting to primary care with acute cough: Diagnostic study. BMJ. 2013;346:f2450.

Povoa P, Coelho L, Almeida E, Fernandes A, Mealha R, Moreira P, Sabino H. Early identification of intensive care unit-acquired infections with daily monitoring of C-reactive protein: a prospective observational study. Crit Care. 2006;10(2):R63.

Menendez R, Martínez R, Reyes S, Mensa J, Filella X, Marcos MA, Martínez A, Esquinas C, Ramirez P, Torres A. Biomarkers improve mortality prediction by prognostic scales in community-acquired pneumonia. Thorax. 2009;64(7):587–91.

Ishimitsu T, Kojima M, Kangawa K, Hino J, Matsuoka H, Kitamura K, Eto T, Matsuo H. Genomic structure of human adrenomedullin gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;203(1):631–9.

Linscheid P, Seboek D, Zulewski H, Keller U, Müller B. Autocrine/paracrine role of inflammation-mediated calcitonin gene-related peptide and adrenomedullin expression in human adipose tissue. Endocrinology. 2005;146(6):2699–708.

Hinson JP, Kapas S, Smith DM. Adrenomedullin, a multifunctional regulatory peptide. Endocr Rev. 2000;21(2):138–67.

Eto T. A review of the biological properties and clinical implications of adrenomedullin and proadrenomedullin N-terminal 20 peptide (PAMP), hypotensive and vasodilating peptides. Peptides. 2001;22:1693–711.

Kitamura K, Sakata J, Kangawa K, Kojima M, Matsuo H, Eto T. Cloning and characterization of cDNA encoding a precursor for human adrenomedullin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;194:720–5.

Di Somma S, Magrini L, Travaglino F, Lalle I, Fiotti N, Cervellin G, Avanzi GC, Lupia E, Maisel A, Hein F, Wagner F, Lippi G. Opinion paper on innovative approach of biomarkers for infectious diseases and sepsis management in the emergency department. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2013;51(6):1167–75.

Struck J, Tao C, Morgenthaler NG, Bergmann A. Identification of an Adrenomedullin precursor fragment in plasma of sepsis patients. Peptides. 2004;25:1369–72.

Schuetz P, Christ-Crain M, Morgenthaler NG, Struck J, Bergmann A, Müller B. Circulating precursor levels of endothelin-1 and adrenomedullin, two endothelium-derived, counteracting substances, in sepsis. Endothelium. 2007;14(6):345–51.

Christ-Crain M, Morgenthaler NG, Struck J, Harbarth S, Bergmann A, Müller B. Mid-regional pro-adrenomedullin as a prognostic marker in sepsis: an observational study. Crit Care. 2005;9(6):R816–24.

Schuetz P, Wolbers M, Christ-Crain M, Thomann R, Falconnier C, Widmer I, Neidert S, Fricker T, Blum C, Schild U, Morgenthaler NG, Schoenenberger R,Henzen C, Bregenzer T, Hoess C, Krause M, Bucher HC, Zimmerli W, Mueller B. Prohormones for prediction of adverse medical outcome in community-acquired pneumonia and lower respiratory tract infections. Crit Care. 2010;14(3):R106.

Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, Hanusa BH, Weissfeld LA, Singer DE, Coley CM, Marrie TJ, Kapoor WN. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:243–50.

Yealy DM, Auble TE, Stone RA, Lave JR, Meehan TP, Graff LG, Fine JM, Obrosky DS, Mor MK, Whittle J, Fine MJ. Effect of increasing the intensity of implementing pneumonia guidelines: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:881–94.

Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, Leeflang MM, Sterne JA, Bossuyt PM. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):529–36.

DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–58.

Cucherat M, Boissel JP, Leizorovicz A, Haugh MC. EasyMA: a program for the meta-analysis of clinical trials. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 1997;53:187–90.

Whiting P, Rutjes AW, Reitsma JB, Bossuyt PM, Kleijnen J. The development of QUADAS: a tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews. J BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003;3:25.

Reitsma JB, Glas AS, Rutjes AW, Scholten RJ, Bossuyt PM, Zwinderman AH. Bivariate analysis of sensitivity and specificity produces informative summary measures in diagnostic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:982–90.

Moses LE, Shapiro D, Littenberg B. Combining independent studies of a diagnostic test into a summary ROC curve: data-analytic approaches and some additional considerations. Stat Med. 1993;12:1293–316.

Albrich, Dusemund F, Rüegger K, Christ-Crain M, Zimmerli W, Bregenzer T, Irani S, Buergi U, Reutlinger B, Mueller B, Schuetz P. Enhancement of CURB65 score with proadrenomedullin (CURB65-A) for outcome prediction in lower respiratory tract infections: derivation of a clinical algorithm. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:112.

Bello, Lasierra AB, Mincholé E, Fandos S, Ruiz MA, Vera E, de Pablo F, Ferrer M, Menendez R, Torres A. Prognostic power of proadrenomedullin in community-acquired pneumonia is independent of aetiology. Eur Respir J. 2012;39(5):1144–55.

Christ-Crain, Morgenthaler NG, Stolz D, Müller C, Bingisser R, Harbarth S, Tamm M, Struck J, Bergmann A, Müller B. Pro-adrenomedullin to predict severity and outcome in community-acquired pneumonia ISRCTN04176397. Crit Care. 2006;10(3):R96.

Courtais, Kuster N, Dupuy AM, Folschveiller M, Jreige R, Bargnoux AS, Guiot J, Lefebvre S, Cristol JP, Sebbane M. Proadrenomedullin, a useful tool for risk stratification in high Pneumonia Severity Index score community acquired pneumonia. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(1):215–21.

Huang DT, Angus DC, Kellum JA, Pugh NA, Weissfeld LA, Struck J, Delude RL, Rosengart MR, Yealy DM. Midregional proadrenomedullin as a prognostic tool in community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2009;136(3):823–31.

Kolditz, Halank M, Schulte-Hubbert B, Bergmann S, Albrecht S, Höffken G. Copeptin predicts clinical deterioration and persistent instability in community-acquired pneumonia. Respir Med. 2012;106(9):1320–8.

Kruger, Ewig S, Giersdorf S, Hartmann O, Suttorp N, Welte T. Cardiovascular and inflammatory biomarkers to predict short- and long-term survival in community-acquired pneumonia: Results from the German Competence Network, CAPNETZ. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(11):1426–34.

Julian-Jimenez, Timón Zapata J, Laserna Mendieta EJ, Sicilia-Bravo I, Palomo-de Los Reyes MJ, Cabezas-Martínez A, Laín-Terés N, Estebaran-Martín J, Lozano-Ancín A, Cuena-Boy R. Diagnostic and prognostic power of biomarkers to improve the management of community acquired pneumonia in the emergency department. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2014;32(4):225–35.

Suberviola B, Castellanos-Ortega A, Llorca J, Ortiz F, Iglesias D, Prieto B. Prognostic value of proadrenomedullin in severe sepsis and septic shock patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;142:w13542.

Lacoma A, Bas A, Tudela P, Giménez M, Mòdol JM, Pérez M, Ausina V, Dominguez J, Prat-Aymerich C. Correlation of inflammatory and cardiovascular biomarkers with pneumonia severity scores. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2014;32(3):140–6.

Edurne Bereciartua Urbietaa, Carmen Mar Medinaa, Alberto Capelastegui Sáizb, Pedro Pablo Espana Yandiolab, Iratxe Ajuria Morentína, Kalliopi Vrotsouc. C reactive protein, procalcitonin and proadrenomedullin in the outcome of hospitalized pneumonia patients. Revista del Laboratorio Clinico. 2011;4(1):23–9.

Renaud B, Schuetz P, Claessens Y-E, Labarère J, Albrich W, Mueller B. Proadrenomedullin improves Risk of Early Admission to ICU score for predicting early severe community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2012;142(6):1447–54.

Morgenthaler NG, Struck J, Alonso C, Bergmann A. Measurement of midregional proadrenomedullin in plasma with an immunoluminometric assay. Clin Chem. 2005;51(10):1823–9.

Mandell LA. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44 Suppl 2:S27–72.

Aronsky D. Assessing the quality of clinical data in a computer-based record for calculating the pneumonia severity index. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2000;7:55–65.

Loke YK. Value of severity scales in predicting mortality from community-acquired pneumonia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. 2010;65(10):884–90.

Marrie TJ. Admission is not always necessary for patients with community-acquired pneumonia in risk classes IV and V diagnosed in the emergency room. Can Respir J. 2007;14(4):212–6.

Albrich WC. Biomarker-enhanced triage in respiratory infections: a proof-of-concept feasibility trial. Eur Respir J. 2013;42:1064–75.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank all authors who provided published data for our meta-analysis.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Availability of data and materials

All the data supporting your findings is contained within the manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

JC designed the study. DL and XLX searched the scientific literature. DL, XLX, YHZ and YXL selected relevant studies. JC and DL provided expertise to the definition of inclusion and exclusion criteria for study eligibility. DL, XLX, YHZ and YXL extracted the study data. DL and YXL conducted statistical analysis. DL drafted the report. JC and XLX performed interpretation, revisions to the draft report and approval of final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Ethics and consent to participate

The present research complies with our national guidelines. Our local ethics committee (Chinese PLA General Hospital Medical Ethics Committee) stated that no formal ethics approval was required in this particular case.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Figure S1. Deek’s funnel plot. Deek’s funnel plot asymmetry test for publication bias (A. for development of complications; B. for prediction of mortality). (TIF 755 kb)

Additional file 2:

Figure S2. SROC curve of the included studies. The numbers in the circle refer to the included studies; Line = regression; the overall area under the SROC curve was 0.74 (95 % CI: 0.70–0.78). (TIF 241 kb)

Additional file 3:

Figure S3. An elevated MR-proADM level was associated with a higher risk of death in CAP. The pooled RR was 5.83 (95 % CI 4.53–7.52). (TIF 215 kb)

Appendices

Appendix 1

Example of search strategy for PubMed

(("adrenomedullin"[MeSH Terms] OR "adrenomedullin"[All Fields]) OR ("Rev ADM"[Journal] OR "adm"[All Fields] OR "Rev ADM"[Journal] OR "adm"[All Fields] OR "ADM"[Journal] OR "adm"[All Fields] OR "ADM"[Journal] OR "adm"[All Fields]) OR proADM[All Fields] OR "midregional proadrenomedullin"[All Fields] OR MR-proADM[All Fields] OR ("proadrenomedullin"[Supplementary Concept] OR "proadrenomedullin"[All Fields])) AND ("respiratory tract infection"[All Fields] OR "respiratory infection"[All Fields] OR "pneumonia"[All Fields] OR "community-acquired pneumonia"[All Fields] OR CAP[All Fields])

Appendix 2

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, D., Xie, L., Zhao, H. et al. Prognostic value of mid-regional pro-adrenomedullin (MR-proADM) in patients with community-acquired pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis 16, 232 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-016-1566-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-016-1566-3