Abstract

Background

The incidence of non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) isolation from humans is increasing worldwide. In England, Wales and Northern Ireland (EW&NI) the reported rate of NTM more than doubled between 1996 and 2006. Although NTM infection has traditionally been associated with immunosuppressed individuals or those with severe underlying lung damage, pulmonary NTM infection and disease may occur in people with no overt immune deficiency.

Here we report the incidence of NTM isolation in EW&NI between 2007 and 2012 from both pulmonary and extra-pulmonary samples obtained at a population level.

Methods

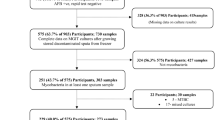

All individuals with culture positive NTM isolates between 2007 and 2012 reported to Public Health England by the five mycobacterial reference laboratories serving EW&NI were included.

Results

Between 2007 and 2012, 21,118 individuals had NTM culture positive isolates. Over the study period the incidence rose from 5.6/100,000 in 2007 to 7.6/100,000 in 2012 (p < 0.001). Of those with a known specimen type, 90 % were pulmonary, in whom incidence increased from 4.0/100,000 to 6.1/100,000 (p < 0.001). In extra-pulmonary specimens this fell from 0.6/100,000 to 0.4/100,000 (p < 0.001).

The most frequently cultured organisms from individuals with pulmonary isolates were within the M. avium-intracellulare complex family (MAC). The incidence of pulmonary MAC increased from 1.3/100,000 to 2.2/100,000 (p < 0.001). The majority of these individuals were over 60 years old.

Conclusion

Using a population-based approach, we find that the incidence of NTM has continued to rise since the last national analysis. Overall, this represents an almost ten-fold increase since 1995. Pulmonary MAC in older individuals is responsible for the majority of this change.

We are limited to reporting NTM isolates and not clinical disease caused by these organisms. To determine whether the burden of NTM disease is genuinely increasing, a standardised approach to the collection of linked national microbiological and clinical data is required.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The frequency of isolation of nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) from human clinical samples is increasing worldwide [1]. In England, Wales and Northern Ireland (EW&NI), the incidence of NTM in all sample types was previously reported to have almost trebled between 1995 (0.9 per 100,000 population) and 2006 (2.9 per 100,000 population) [2].

Unlike Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which is a genuine pathogen, the largely environmental NTM have been often associated with conditions of host impaired immunity, such as primary immunodeficiency, HIV or the use of immunosuppressive medication [3]. Increasingly, NTM are isolated in immunocompetent individuals, with or without pre-existing structural lung damage [4]. It is not clear why this is so, and possible explanations include an increase in the number of individuals with structural lung damage making them more susceptible to mycobacterial infection, more mycobacteria in the environment, improved laboratory detection techniques, a greater awareness of their potential relevance - resulting in more frequent mycobacterial culture being performed, or the result of more investigation to exclude M. tuberculosis.

Here, using population-based data, we report the incidence of NTM isolation in EW&NI between 2007 and 2012. We demonstrate that whilst there has been a significant increase in a number of NTM, the overall rise is largely explained by pulmonary Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex.

Methods

All culture positive NTM isolates between 2007 and 2012 reported to Public Health England (PHE) by the five mycobacterial reference laboratories serving EW&NI were included. Age and sex were routinely collected, along with the site of the specimen and NTM species identified from the culture. Between 2007 and 2012, M. avium, M. intracellulare and other related organisms, (eg M. chimaera), were grouped as M. avium-intracellulare complex (MAC). The rapid growers within M. abscessus family (eg M. abscessus ssp. abscessus, M. abscessus ssp. bolletii, and M. abscessus ssp. massiliense) were identifed as M. abscessus.

Isolates were probabilistically de-duplicated using patient identifiers to report each individual once [5], based on their earliest specimen date between 2007 and 2012. If an individual had multiple NTM organisms isolated, the organism with the earliest specimen date was included. The site of infection was inferred from the specimen site.

The annual incidence of NTM was calculated using the de-duplicated individual level NTM data and mid-year population estimates from the Office of National Statistics. A chi-squared test for trend was used to analyse the change in incidence between 2007 and 2012. Confidence intervals for incidence were calculated assuming a Poisson distribution for the number of events. All analyses were conducted using Stata 13.1, Stata Corporation, Texas, USA. Incidence rates are expressed per 100,000 population. Means are reported with standard deviation.

Results

Between 2007 and 2012, 21,118 individuals had NTM culture positive isolates in EW&NI. The overall incidence of NTM increased from 5.6/100,000 (n = 3,126, 95 % CI 5.4–5.7) to 7.6/100,000 (n = 4,454, 95 % CI 7.4–7.9) (p < 0.001; Fig. 1). 16.2 % of individuals had cultures positive for M. gordonae. As this is considered non-pathogenic in much of the literature, the rates were recalculated without these isolates. Again the incidence rose (from 4.8/100,000 (n = 2,718, 95 % CI 4.6–4.9) to 6.3/100,000 (n = 3,651, 95 % CI 6.2–6.5), p < 0.001). During the study period 46 different mycobacterial species were identified. More than one NTM species was isolated in 2,100 (10 %) individuals. Species could not be identified in 2.4 %.

Of those with a known specimen site (85.0 %, n = 17,932), 90.9 % (n = 16,294) had a pulmonary isolate. Fifty-eight percent of these were in men; and the mean (± standard deviation) age of the pulmonary population was 60 ± 20 years. This compares to 53 ± 25 years in those with extra-pulmonary isolates. Ages are expressed as age ± standard deviation.

In people with pulmonary isolates, the incidence rose from 4.0/100,000 (n = 2,241, 95 % CI 3.8–4.1) to 6.1/100,000 (n = 3,551, 95 % CI 5.9–6.3, p < 0.001). In contrast, over the same period it fell in individuals with extra-pulmonary isolates (0.6/100,000, 95 % CI 0.58–0.63 to 0.4/100,000, 95 % CI 0.39–0.41, p < 0.001). 16.6 % of individuals with pulmonary isolates had cultures positive for M. gordonae. As above, incidence rates were recalculated without these isolates. Incidence rose from 3.4/100,000 (n = 1,893, 95 % CI 3.3–3.5) to 5.0/100,000 (n = 2,905, 95 % CI 4.9–5.1, p < 0.001).

Organisms in pulmonary samples

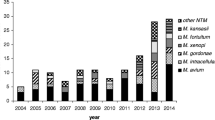

The most frequent NTM cultured from pulmonary samples was M. avium-intracellulare complex (MAC; 35.6 %, n = 5,800). Other organisms commonly isolated were M. gordonae (16.7 %), M. chelonae (9.6 %), M. fortuitum (8.2 %), M. kansasii (5.9 %), M. xenopi (5.9 %), and M. abscessus (5.0 %) (Table 1 and Fig. 2).

The incidence of individuals with pulmonary MAC isolates increased from 1.3 (95 % CI 1.2–1.4) in 2007 to 2.2 (95 % CI 2.1–2.4) in 2012 (p < 0.001). This increase was observed in both males and females (Fig. 3). The majority of pulmonary MAC was isolated from older individuals – with around two-thirds of men and women being aged over 60 (Fig. 4). There was also a significant increase in incidence of M. chelonae, M. fortuitum and M. gordonae (p < 0.001); whilst that of M. kansasii fell (p < 0.001).

M. abscessus had a bi-phasic age distribution with peaks within the age groups 10–19 and 70–79 years. This was unlike other rapid growers such as M. fortuitum and M. chelonae, where the incidence rose steadily with age (Fig. 5).

Organisms in extra-pulmonary samples

The most frequent organisms cultured from extra-pulmonary samples were MAC (34 %), M. chelonae (15.8 %) and M. gordonae (14.3 %) (Table 1). Between 2007 and 2012, there was no significant change in incidence in extra-pulmonary MAC isolates (Fig. 3). Unlike other specimen sites, individuals with cultures from lymph nodes were younger, with a mean age of 21 ± 25 years. In these individuals, the most frequent organisms were MAC (62.7 %), M. malmoense (14.8 %) and M. chelonae (10.9 %). M. marinum accounted for 28.7 % of cutaneous isolates.

Discussion

This population-based study demonstrates that the NTM incidence in submitted samples from EW&NI has continued to rise since the last national investigation [2]. Much of this appears to be due to an increase in NTM in pulmonary isolates, most frequently obtained from older individuals. MAC was the commonest group of cultured organisms from both pulmonary and extra-pulmonary sites. It is noteworthy that the incidence of extra-pulmonary isolates decreased over the same time period over the same time period.

The observed rise in the incidence of NTM in EW&NI is in line with reports from other countries [6, 7], though not Scotland, where there has been no change between 2000 and 2010 [8]. Our finding of pulmonary MAC being the largest contributor to NTM incidence is consistent with a population-based study from Oregon, USA [6].

M. abscessus demonstrated a spike in incidence in both younger and older patients, with the majority of isolates found in individuals less than 30 years. Due to the lack of clinical data, we cannot relate this directly to cystic fibrosis (CF), though it is likely that this contributes to the isolates obtained from the younger population where it is an important clinical problem [9]. This is consistent with a recent report from Scotland [8].

M. chelonae and M. mucogenicum were associated with bloodstream infections. 70 % of cutaneous isolates were M. marinum or rapidly growing NTM, which has also been noted by others [10].

There are several possible explanations for the increase in NTM isolation. These include recent environmental changes leading to more NTM in soil or water [3]. In support of this, Khan et al. [11] demonstrated a significant increase in skin sensitization to M. intracellulare in the general population in the United States between 1971 and 1972 and 1999–2000. A true rise in the amount of NTM in the environment should also be reflected by a similar increase in extra-pulmonary cultures. However this has actually declined, suggesting that environmental factors are not the only explanation.

More individuals may now be susceptible to pulmonary NTM colonisation and disease. Older males, who were most likely to have a positive NTM culture, are a population with more chronic respiratory disease requiring prescribed drug therapies (including inhaled corticosteroids) that increase the risk of NTM lung disease [12]. Furthermore, the number of people using immunosuppressive and biological agents is rising. Brode et al. [13] reported that anti-TNF therapy doubled the risk of NTM disease (OR 2.19, 95 % CI 1.10–4.37). Also, a patient’s underlying clinical illness may be relevant. For example, rheumatoid arthritis has itself been associated with NTM disease [14, 15].

Clearly these explanations are not mutually exclusive; and over time could lead to a yet further increase in incidence as clinicians become more aware of NTM disease and so perform more mycobacterial diagnostic tests.

A strength of our study is that we are confident we are counting only single isolates from individuals, and hence avoiding duplication (and inflation) of our results. The natural history of NTM (where an individual will isolate often multiple samples over an extended period of time) means that this is a common problem when dealing with this condition [2]. We believe that the absolute number of NTM isolates being reported to Public Health England has genuinely increased. However as only the earliest culture result was included in our study in those individuals who had positive cultures of more than one NTM organism (10 %), there is a risk we may have introduced bias towards rapid growers at the expense of slower growers. Despite this, the predominant NTM was MAC, a slow-growing group of organisms.

To determine whether the burden of NTM disease is also increasing requires an understanding of current clinical and laboratory practice. In EW&NI there is no standardised approach to the investigation of suspected NTM patients, and the systematic collection of relevant clinical data related to NTM isolates is limited. This needs to change if we are to better understand NTM disease and improve on current management strategies and outcomes.

Conclusion

The continuing rise in the isolation of NTM between 2007 and 2012, driven primarily by pulmonary MAC in older individuals warrants further investigation. It is now imperative that standardised clinical data are collected on all individuals with positive NTM isolates across the country to determine if there is a genuine increase in NTM disease. This will allow determination of clinical risk groups and reasons for this increase, and justify targeting the development of the management of pulmonary MAC.

Abbreviations

- CF:

-

cystic fibrosis

- EW&NI:

-

England, Wales and Northern Ireland

- NTM:

-

nontuberculous mycobacteria

- PHE:

-

Public Health England

References

Prevots DR, Marras TK. Epidemiology of human pulmonary infection with nontuberculous mycobacteria: a review. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36:13–34.

Moore JE, Kruijshaar ME, Ormerod LP, Drobniewski F, Abubakar I. Increasing reports of non-tuberculous mycobacteria in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, 1995–2006. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:612.

Thomson RM, NTM working group at Queensland TB Control Centre and Queensland Mycobacterial Reference Laboratory. Changing epidemiology of pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacteria infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1576–83.

Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, Catanzaro A, Daley C, Gordin F, Holland SM, Horsburgh R, Huitt G, Iademarco MF, Iseman M, Olivier K, Ruoss S, von Reyn CF, Wallace RJ Jr, Winthrop K. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367–416.

Aldridge RW, Shaji K, Hayward AC, Abubakar I. Accuracy of probabilistic linkage using the enhanced matching system for public health and epidemiological studies. PLoS One. 2015;10, e0136179.

Henkle E, Hedberg K, Schafer S, Novosad S, Winthrop KL. Population-based Incidence of pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease in Oregon 2007 to 2012. Annals ATS. 2015;12:642–7.

Hoefsloot W, van Ingen J, Andrejak C, Angeby K, Bauriaud R, Bemer P, Beylis N, Boeree MJ, Cacho J, Chihota V, Chimara E,Churchyard G, Cias R, Daza R, Daley CL, Dekhuijzen PN, Domingo D, Drobniewski F, Esteban J, Fauville-Dufaux M, Folkvardsen DB, Gibbons N, Gómez-Mampaso E, Gonzalez R, Hoffmann H, Hsueh PR, Indra A, Jagielski T, Jamieson F, Jankovic M, Jong E, Keane J, Koh WJ, Lange B, Leao S, Macedo R, Mannsåker T, Marras TK, Maugein J, Milburn HJ, Mlinkó T, Morcillo N, Morimoto K,Papaventsis D, Palenque E, Paez-Peña M, Piersimoni C, Polanová M, Rastogi N, Richter E, Ruiz-Serrano MJ, Silva A, da Silva MP,Simsek H, van Soolingen D, Szabó N, Thomson R, Tórtola Fernandez T, Tortoli E, Totten SE, Tyrrell G, Vasankari T, Villar M,Walkiewicz R, Winthrop KL, Wagner D; Nontuberculous Mycobacteria Network European Trials Group. The geographic diversity of nontuberculous mycobacteria isolated from pulmonary samples: an NTM-NET collaborative study. Eur Respir J. 2013;42:1604–13.

Russell CD, Claxton P, Doig C, Seagar AL, Rayner A, Laurenson IF. Non-tuberculous mycobacteria: a retrospective review of Scottish isolates from 2000 to 2010. Thorax. 2014;69:593–5.

Qvist T, Pressler T, Hoiby N, Katzenstein TL. Shifting paradigms of nontuberculous mycobacteria in cystic fibrosis. Respir Res. 2014;15:41.

Gonzalez-Santiago TM, Drage LA. Nontuberculous Mycobacteria: Skin and Soft Tissue Infections. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:563–77.

Khan K, Wang J, Marras TK. Nontuberculous mycobacterial sensitization in the United States: national trends over three decades. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:306–13.

Andréjak C, Nielsen R, Thomsen VØ, Duhaut P, Sørensen HT, Thomsen RW. Chronic respiratory disease, inhaled corticosteroids and risk of non-tuberculous mycobacteriosis. Thorax. 2013;68:256–62.

Brode SK, Jamieson FB, Ng R, Campitelli MA, Kwong JC, Paterson JM, Li P, Marchand-Austin A, Bombardier C, Marras TK. Increased risk of mycobacterial infections associated with anti-rheumatic medications. Thorax. 2015;70:677–82.

Winthrop KL, Baxter R, Liu L, Varley CD, Curtis JR, Baddley JW, McFarland B, Austin D, Radcliffe L, Suhler EB, Choi D, Rosenbaum JT, Herrinton LJ. Mycobacterial diseases and antitumour necrosis factor therapy in USA. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:37–42.

Liao TL, Lin CH, Shen GH, Chang CL, Lin CF, Chen DY. Risk for mycobacterial disease among patients with rheumatoid arthritis, Taiwan, 2001–2011. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:1387–95.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Kunju Shaji for his help in preparing the database for this study.

This work was supported by funding from Public Health England. Since Public Health England (PHE) was set up in 2013, powers under Regulation 3 of Section 251 of the NHS Act (2006) (originally enacted under Section 60 of the Health and Social Care Act 2001) have been devolved to PHE in order to collect and analyse confidential patient information with a view to recognising trends in communicable diseases and other risks to public health, and controlling and preventing the spread of such diseases and risks. Ethics approval was not required for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

NMS participated in study design, data collection and analysis and drafted the manuscript. JAD participated in study design, data collection and analysis and helped to draft the manuscript. LFA participated in study design and data analysis. MKL contributed to study design and helped draft the manuscript. JK helped draft the manuscript. HLT contributed to study design and helped draft the manuscript. ML and IA conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination and helped draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Marc Lipman and Ibrahim Abubakar are joint last authors

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Shah, N.M., Davidson, J.A., Anderson, L.F. et al. Pulmonary Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare is the main driver of the rise in non-tuberculous mycobacteria incidence in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, 2007–2012. BMC Infect Dis 16, 195 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-016-1521-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-016-1521-3