Abstract

Background

West Nile virus (WNV) has emerged as one of the most common causes of epidemic meningoencephalitis worldwide. Most human infections are asymptomatic. However, neuroinvasive disease characterized by meningitis, encephalitis and/or acute flaccid paralysis is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Although outbreaks have been reported in Asia, human WNV infection has not been previously reported in Sri Lanka.

Methods

Sera and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from 108 consecutive patients with a clinical diagnosis of encephalitis admitted to two tertiary care hospitals in Colombo, Sri Lanka were screened for WNV IgM antibody using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Positive results were confirmed using plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT). Patient data were obtained from medical records and by interviewing patients and care-givers.

Results

Three of the 108 patients had WNV IgM antibody in serum and one had antibody in the CSF. The presence of WNV neutralizing antibodies was confirmed in two of the three patients using PRNT. Two patients had presented with the clinical syndrome of meningoencephalitis while one had presented with encephalitis. One patient had CSF lymphocytic pleocytosis, one had neutrophilic pleocytosis while CSF cell counts were normal in one. CSF protein showed marginal increase in two patients.

Conclusions

This is the first report of human WNV infection identified in patients presenting with encephalitis or meningoencephalitis in Sri Lanka. There were no clinical, routine laboratory or radiological features that were distinguishable from other infectious causes of meningoencephalitis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

West Nile virus (WNV) is one of the most widely distributed, medically important arboviral infections that has caused major outbreaks in many parts of the world [1]. Although the initial WNV outbreaks were confined to rural areas in Africa [1], it is now the leading cause of encephalitis in USA, Europe and Australia [2, 3]. Initial WNV outbreaks were associated with only a few cases of severe neurological diseases. However, neuroinvasive disease is now more frequent and the case fatality rates range from 4.2 to 18.6 % in more recent epidemics [1, 4, 5]. WNV is considered to be one of the most important emerging flaviviral infections in the world, due to the increase in the number of cases with expansion in geographical distribution, and its association with severe neurological disease [6, 7].

WNV is a zoonotic infection, where the virus cycles between mosquitoes and birds. The Culex genus of mosquitoes are the main vectors while passerine birds act as amplifying hosts [1]. Humans and mammals are usually incidental, dead-end hosts as viral titers in mammals are insufficient to infect mosquitoes for further transmission to other mammals [8]. WNV results in neuroinvasive disease in less than 1 % (approximately 1 in 150) of infected individuals, while asymptomatic infections occur in around 80 % [9, 10]. Approximately 20 % of infected individuals develop WN fever, which is an undifferentiated flu-like illness that occurs 2–14 days after an infectious mosquito bite. This is characterized by fever, myalgia, gastrointestinal symptoms and sometimes a macular-papular rash [9]. WN fever may mimic the clinical syndromes of other flavivirus infections such as dengue fever. WNV neuroinvasive disease manifests as meningitis, encephalitis, asymmetric acute flaccid paralysis or a mixed pattern of these syndromes. Encephalitis is more common than meningitis in older age groups, and is commonly associated with extrapyramidal features while acute flaccid paralysis may lead to respiratory paralysis. After the acute infection, many patients experience persistent symptoms, such as fatigue, memory impairment, weakness, headache, and balance problems.

Encephalitis is a notifiable disease in Sri Lanka and annually, 165–220 cases are reported to the Epidemiology Unit of Sri Lanka. However, in 2013, a large outbreak of encephalitis occurred with 141 cases of encephalitis being reported in the first 2 months of the year. Although cases of encephalitis occur throughout the year in Sri Lanka, there are usually two peaks in the number of cases reported (Fig. 1) [11–13]. These peaks coincide with the monsoon rain seasons in Sri Lanka and are likely to reflect an increase in vector densities caused by increased mosquito breeding in stagnant collections of rainwater. These two peaks also coincide with the latter part of the migratory bird season. This provides the requisite environment for the maintenance of the zoonotic WNV life-cycle between mosquitoes and birds. The Culex genus of mosquitoes are endemic while passerine birds are both endemic and migratory in Sri Lanka. Although human WNV infection has not been previously reported in Sri Lanka, it has reportedly caused several outbreaks in neighboring India, including Kerala and Tamil Nadu, which are in close proximity to Sri Lanka [14, 15].

Given the conducive environment for transmission, WNV has the potential to emerge as a major cause of meningoencephalitis in Sri Lanka. In this study, we report the first identification of human WNV infection in Sri Lanka in patients presenting with meningoencephalitis.

Methods

Patients

108 patients with clinical syndromes of encephalitis or meningoencephalitis, who were admitted to two of the largest tertiary care hospitals in Sri Lanka (the National Hospital of Sri Lanka and the Lady Ridgeway Hospital for Children), were included in the study following informed written consent. In the instances where children were recruited, informed written consent was obtained from the guardian. The study was approved by the Ethic Review Committees of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Colombo and those of the two hospitals. Clinical and laboratory data including cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis, CT or MRI scan results were recorded. Serum and CSF were obtained from all patients and stored at -80 °C until analyzed.

ELISA for detection of WNV

WNV Detect™ IgM enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (InBios, USA) was used for the initial screening for WNV infection. In sera and CSF that tested positive for WNV, ELISA for Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) and dengue virus were also performed to eliminate potential false positive results due to the cross-reactivity between the antibodies of these flaviviruses. JE Detect™ IgM ELISA (InBios, USA) was used for the detection of antibodies in human serum to determine exposure to JEV. Calculation of the immune status ratio (ISR) was done according to the manufacturer’s instructions that consider ISR units of > 6.0 as positive for acute JEV infection. Serum and CSF were also tested for the presence of anti-dengue virus antibodies by using a commercial capture-IgM and IgG ELISA (Panbio, Brisbane, Australia). Panbio units of > 11 were considered positive for acute dengue infection.

Plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT) for WNV

PRNT was done at the National West Nile virus reference laboratory of the National University of Singapore. Serum samples were inactivated at 56 °C for 30 min, and diluted 100 times in RPMI medium containing 2 % FBS (virus diluent). A 10-step 2-fold serial dilution was carried out using virus diluent before 500 PFU of WNV was added to 500 μl of each serum dilution. The rest of the assay was performed as previously described [16].

WNV specific RT-PCR

Viral RNA was extracted from serum using QIAmp viral RNA mini kit (Qiagen, Germany). RNA was reverse transcribed and the PCR was performed by using primer and conditions as previously described [17].

Laboratory criteria for diagnosis of WNV infection

WNV infection was diagnosed as ‘definite’ in patients with WNV-specific IgM in serum or CSF (detected using ELISA) and confirmed with the WNV-specific PRNT assay. WNV infection was diagnosed as ‘probable’ in patients with WNV-specific IgM in serum or CSF, but without JEV or dengue virus IgM (detected using ELISA) in the absence of WNV-specific PRNT confirmation.

Results

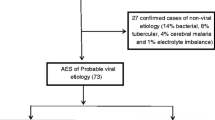

Of the 108 patients recruited into the study, 3 were diagnosed to have WNV neuroinvasive disease based on their clinical syndromes and confirmed by laboratory results (Table 1). WNV IgM antibodies were detected in the serum of all three patients and the CSF of Patient #2. CSF of the other two patients could not be tested due to insufficient quantities of CSF. Because antibodies to JEV and dengue virus can cross-react and give rise to false-positive results in the WNV IgM ELISA test [18, 19], we tested both sera and CSF for the presence of JEV-specific IgM antibodies and dengue virus-specific IgM and IgG antibodies. Cross-reactivity was evident in Patients #1 and #2 (Table 1). None of the samples tested positive for WNV on RT-PCR. In order to confirm WNV infection, the seropositive sera of Patients #1 and #2 were analysed for the presence of neutralizing antibodies to WNV, using the PRNT assay. Both patients had PRNT50 neutralizing antibody titers of 800 against WNV. Accordingly, Patients #1 and #2 were diagnosed to have definite WNV infection while Patient #3 was diagnosed to have probable WNV infection.

The clinical and laboratory features of these patients are shown in Table 2. Two were males and one female, with ages ranging from 17 to 49 years. All three patients presented with abrupt onset fever and altered sensorium, predominantly confusion. Patients #2 and #3 had prominent headache, and Patients #1 and #3 developed generalised tonic-clonic seizures. Neck rigidity and increased tone was noted in Patients #2 and #3. Neutrophil leucocytosis was noted in the peripheral blood of two patients. Lymphocytic pleocytosis was noted in the CSF of one patient while neutrophils predominated in the CSF of Patient #2. CSF analysis was normal in Patient #1. CSF protein was marginally elevated in two of the three patients. Generalised cerebral oedema was noted in Patients #2 and #3 on CT brain imaging. MRI brain was done in only Patient #3 which showed meningeal enhancement. All three patients were treated with empirical intravenous antibiotics and aciclovir for variable periods and all patients recovered to their pre-morbid states.

Discussion

This is the first report of human WNV infection in Sri Lanka presenting with encephalitis and meningoencephalitis. Three of 108 patients (2.8 %) presenting with a clinical diagnosis of encephalitis or meningoencephalitis admitted to hospital were diagnosed to have WNV infection retrospectively when serum and CSF were screened for WNV IgM antibodies. Since dengue and Japanese encephalitis are endemic in Sri Lanka and anti-flavivirus antibodies may cross-react in ELISA to give false-positive results, WNV infection in Patients #1 and #2 were confirmed by specific PRNT assay.

Detection of WNV-specific IgM antibodies in serum and CSF remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of human WNV disease. IgM antibodies to WNV are usually detectable by ELISA in 75 % by day 4 post-infection and 95 % by day 7 post-infection in WNV infected patients [20]. Since IgM antibodies do not readily cross the blood brain barrier, detection of WNV IgM in CSF is diagnostic of neuroinvasive disease. WNV IgM antibody was detected in the CSF in Patient #2. However, unlike most IgM responses, WNV IgM antibody can persist for 6 months or longer in both serum and CSF [21]. The PRNT is the most specific diagnostic test for WNV and can help distinguish serologic cross-reactions caused by other flaviviruses. However, this test is not commercially available, is tedious, and can only be performed in laboratories with the relevant capabilities. Nucleic acid amplification for viral detection is highly specific, but is of limited sensitivity (less than 15 % for serum) since viraemia occurs early before the onset of symptoms, is of low titer and is short-lived [22].

Peripheral blood counts can be normal in patients with WNV neuroinvasive disease, or can demonstrate anaemia, thrombocytopenia, leukocytosis or leukopenia [20]. Typical CSF findings in WNV neuroinvasive disease include moderate lymphocytic pleocytosis (usually <500 cells/μl) with elevated protein (usually <150 mg/dl) and slightly low or normal levels of glucose [23]. However, neutrophils may predominate in early infection in up to 45 % of patients, while 3–5 % of patients with meningitis or encephalitis may have normal CSF cell counts [23]. The presence of abnormalities on neuroimaging has been variable ranging from none to 70 % of reported cases [20].

Of the three patients reported here, two (Patient #2 and #3) presented with clinical features of meningoencephalitis while one presented with encephalitis indistinguishable from other infectious aetiologies presenting with similar syndromes. Although the association of extrapyramidal features and flaccid paralysis is reported to be common in WNV neuroinvasive disease [20], our patients did not demonstrate such distinguishing clinical characteristics. Of the two patients who had peripheral neutrophil leucocytosis, in Patient #3, it is likely to be related to seizures given that the inflammatory marker (ESR) was normal. Bacteriological screening of all three patients, which included blood culture and CSF Gram stain and culture, were negative. The presence of neutrophil predominance in CSF has been suggested as a possible diagnostic clue of WNV infection [23], but only Patient #2 of our three patients had CSF neutrophilic pleocytosis.

Conclusion

In summary, the clinical, routine laboratory or radiological features of our patients did not provide any diagnostic clues of WNV infection; diagnosis was established based on serological testing for WNV and excluding other possible aetiologies. It is thus reasonable that all patients presenting with a clinical syndrome of meningitis, encephalitis, asymmetric acute flaccid paralysis or any combination of these three syndromes be screened for WNV IgM since this report has now established the occurrence of human WNV disease in Sri Lanka. An accurate diagnosis will help avoid inappropriate treatment and allow correct prognostication. Moreover, this will enable timely evaluation of possible outbreaks of a vector-borne disease that has the potential to emerge as a major cause of meningoencephalitis as it has done in other WNV endemic countries such as the United States of America. This will also allow the Sri Lankan public health authorities to institute timely preventive measures. By extrapolating that neuroinvasive disease occurs in 1 in 150 to 1 in 250 WNV infections [24], our report of three cases would imply that there would be between 450 and 750 cases of WNV infection. As our sample included only patients admitted to two major hospitals in Colombo, Sri Lanka, and since it did not include patients presenting with acute flaccid paralysis, the actual number of WNV infections is likely to be much higher than our estimate.

Abbreviations

- WNV:

-

West Nile virus

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- JEV:

-

Japanese Encephalitis Virus

- MRI:

-

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- FBS:

-

Fetal bovine serum

- PRNT:

-

Plaque reduction neutralization test

References

Kramer LD, Styer LM, Ebel GD. A global perspective on the epidemiology of West Nile virus. Annu Rev Entomol. 2008;53:61–81.

Blitvich BJ. Transmission dynamics and changing epidemiology of West Nile virus. Anim Health Res Rev. 2008;9(1):71–86.

Pradier S, Lecollinet S, Leblond A. West Nile virus epidemiology and factors triggering change in its distribution in Europe. Rev Sci Tech. 2012;31(3):829–44.

Amanna IJ, Slifka MK. Current trends in West Nile virus vaccine development. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2014;13(5):589–608.

Huhn GD, Austin C, Langkop C, Kelly K, Lucht R, Lampman R, et al. The emergence of west nile virus during a large outbreak in Illinois in 2002. AmJTrop Med Hyg. 2005;72(6):768–76.

Daep CA, Munoz-Jordan JL, Eugenin EA. Flaviviruses, an expanding threat in public health: focus on dengue, West Nile, and Japanese encephalitis virus. J Neurovirol. 2014;20(6):539–60.

Weaver SC, Reisen WK. Present and future arboviral threats. Antivir Res. 2010;85(2):328–45.

Suthar MS, Diamond MS, Gale Jr M. West Nile virus infection and immunity. Nat Rev. 2013;11(2):115–28.

Debiasi RL. West nile virus neuroinvasive disease. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2011;13(4):350–9.

Hart Jr J, Tillman G, Kraut MA, Chiang HS, Strain JF, Li Y, et al. West Nile virus neuroinvasive disease: neurological manifestations and prospective longitudinal outcomes. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:248.

Ministry of Health. Weekly Epidemiological Report 2012. Retrieved from:http://epid.gov.lk/web/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=148&Itemid=449&lang=en

Ministry of Health. Weekly Epidemiological Report 2011. Retrieved from:http://epid.gov.lk/web/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=148&Itemid=449&lang=en

Ministry of Health. Weekly Epidemiological Report 2013. Retrieved from:http://epid.gov.lk/web/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=148&Itemid=449&lang=en

Anukumar B, Sapkal GN, Tandale BV, Balasubramanian R, Gangale D. West Nile encephalitis outbreak in Kerala, India, 2011. J Clin Virol. 2014;61(1):152–5.

Gajanana A, Thenmozhi V, Samuel PP, Reuben R. A community-based study of subclinical flavivirus infections in children in an area of Tamil Nadu, India, where Japanese encephalitis is endemic. Bull World Health Organ. 1995;73(2):237–44.

Chua AJ, Vituret C, Tan ML, Gonzalez G, Boulanger P, Ng ML, et al. A novel platform for virus-like particle-display of flaviviral envelope domain III: induction of Dengue and West Nile virus neutralizing antibodies. Virol J. 2013;10:129.

Bondre VP, Jadi RS, Mishra AC, Yergolkar PN, Arankalle VA. West Nile virus isolates from India: evidence for a distinct genetic lineage. J Gen Virol. 2007;88(Pt 3):875–84.

Koraka P, Zeller H, Niedrig M, Osterhaus AD, Groen J. Reactivity of serum samples from patients with a flavivirus infection measured by immunofluorescence assay and ELISA. Microbes Infect. 2002;4(12):1209–15.

Mansfield KL, Horton DL, Johnson N, Li L, Barrett AD, Smith DJ, et al. Flavivirus-induced antibody cross-reactivity. J Gen Virol. 2011;92(Pt 12):2821–9.

Debiasi RL, Tyler KL. West Nile virus meningoencephalitis. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2006;2(5):264–75.

Roehrig JT, Nash D, Maldin B, Labowitz A, Martin DA, Lanciotti RS, et al. Persistence of virus-reactive serum immunoglobulin m antibody in confirmed west nile virus encephalitis cases. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9(3):376–9.

Lanciotti RS, Kerst AJ. Nucleic acid sequence-based amplification assays for rapid detection of West Nile and St. Louis encephalitis viruses. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39(12):4506–13.

Tyler KL, Pape J, Goody RJ, Corkill M, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK. CSF findings in 250 patients with serologically confirmed West Nile virus meningitis and encephalitis. Neurology. 2006;66(3):361–5.

Mostashari F, Bunning ML, Kitsutani PT, Singer DA, Nash D, Cooper MJ, et al. Epidemic West Nile encephalitis, New York, 1999: results of a household-based seroepidemiological survey. Lancet. 2001;358(9278):261–4.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by the National Research Council, Sri Lanka (grant number: No. 11-075).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JL: acquisition of data and carried out experiments. GNM: conceptual design and writing the manuscript. AJSH: Carried out experiments and critically revised it for intellectual content. NML: critically revised it for intellectual content and was involved in designing experiments. CA: study design and statistical input. TC: conceptual design, acquisition of data and funding, and writing the manuscript. All authors have given final approval of the version to be published.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Lohitharajah, J., Malavige, G.N., Chua, A.J.S. et al. Emergence of human West Nile Virus infection in Sri Lanka. BMC Infect Dis 15, 305 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-015-1040-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-015-1040-7