Abstract

Neisseria gonorrhoeae has developed antimicrobial resistance (AMR) to all drugs previously and currently recommended for empirical monotherapy of gonorrhoea. In vitro resistance, including high-level, to the last option ceftriaxone and sporadic failures to treat pharyngeal gonorrhoea with ceftriaxone have emerged. In response, empirical dual antimicrobial therapy (ceftriaxone 250–1000 mg plus azithromycin 1–2 g) has been introduced in several particularly high-income regions or countries. These treatment regimens appear currently effective and should be considered in all settings where local quality assured AMR data do not support other therapeutic options. However, the dual antimicrobial regimens, implemented in limited geographic regions, will not entirely prevent resistance emergence and, unfortunately, most likely it is only a matter of when, and not if, treatment failures with also these dual antimicrobial regimens will emerge. Accordingly, novel affordable antimicrobials for monotherapy or at least inclusion in new dual treatment regimens, which might need to be considered for all newly developed antimicrobials, are essential. Several of the recently developed antimicrobials deserve increased attention for potential future treatment of gonorrhoea. In vitro activity studies examining collections of geographically, temporally and genetically diverse gonococcal isolates, including multidrug-resistant strains particularly with resistance to ceftriaxone and azithromycin, are important. Furthermore, understanding of effects and biological fitness of current and emerging (in vitro induced/selected and in vivo emerged) genetic resistance mechanisms for these antimicrobials, prediction of resistance emergence, time-kill curve analysis to evaluate antibacterial activity, appropriate mice experiments, and correlates between genetic and phenotypic laboratory parameters, and clinical treatment outcomes, would also be valuable. Subsequently, appropriately designed, randomized controlled clinical trials evaluating efficacy, ideal dose, toxicity, adverse effects, cost, and pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamics data for anogenital and, importantly, also pharyngeal gonorrhoea, i.e. because treatment failures initially emerge at this anatomical site. Finally, in the future treatment at first health care visit will ideally be individually-tailored, i.e. by novel rapid phenotypic AMR tests and/or genetic point of care AMR tests, including detection of gonococci, which will improve the management and public health control of gonorrhoea and AMR. Nevertheless, now is certainly the right time to readdress the challenges of developing a gonococcal vaccine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Review

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated in 2008 that 106 million new gonorrhoea cases occur among adults annually worldwide [1]. If the gonococcal infections are not detected and/or appropriately treated, they can result in severe complications and sequelae such as pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, ectopic pregnancy, first trimester abortion, neonatal conjunctivitis leading to blindness and, less frequently, male infertility and disseminated gonococcal infections. Gonorrhoea also increases the transmission and acquisition of HIV. Thus, gonorrhoea causes significant morbidity and socioeconomic consequences globally [1, 2]. In the absence of a gonococcal vaccine, public health control of gonorrhoea is relying on effective, accessible and affordable antimicrobial treatment, i.e., combined with appropriate prevention, diagnostics (index cases and traced sexual contacts), and epidemiological surveillance. The antimicrobial treatment should cure individual gonorrhoea cases, to reduce the risk of complications, and end further transmission of the infection, which is a crucial to decrease the gonorrhoea burden in a population.

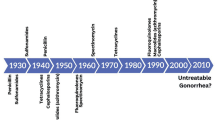

Unfortunately, Neisseria gonorrhoeae has developed resistance to all antimicrobials introduced for treatment of gonorrhoea since the mid-1930s, when sulphonamides were introduced. The resistance to many antimicrobials has also rapidly, within only 1–2 decades, emerged and spread internationally [3–6]. The bacterium has utilized mainly all known mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance (AMR): inactivation of the antimicrobial, alteration of antimicrobial targets, increased export (e.g., through efflux pumps such as MtrCDE) and decreased uptake (e.g. through porins such as PorB). The mechanisms that change the permeability of the gonococcal cell are particularly concerning because these decrease the susceptibility to a wide range of antimicrobials with different modes of action, e.g., penicillins, cephalosporins, tetracyclines and macrolides [3, 5–8]. At present, the prevalence of N. gonorrhoeae resistance to most antimicrobials earlier recommended for treatment worldwide, such as sulphonamides, penicillins, earlier generation cephalosporins, tetracyclines, macrolides and fluoroquinolones, is high internationally [2–15]. In most countries, the only options for first-line empirical antimicrobial monotherapy are currently the extended-spectrum cephalosporins (ESCs) cefixime (oral) and particularly the more potent ceftriaxone (injectable) [2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 10–15].

Conventional antimicrobial treatment of gonorrhoea

Treatment of gonorrhoea is mainly administered directly observed before any laboratory results are available, i.e., empirical therapy using first-line recommendations according to evidence-based management guidelines that are crucial to regularly update based on high quality surveillance data. Ideally, the recommended first-line therapy should be highly effective, widely available and affordable in appropriate quality and dose, lack toxicity, possible to administer as single dose, and cure >95 % of infected patients [2, 16]. However, levels of >1 % and >3 % AMR in high-frequency transmitting populations have also been suggested as thresholds for altering recommended treatment [16, 17]. Additional criteria, e.g. prevalence, local epidemiology, diagnostic tests, transmission frequency, sexual contact tracing strategies, and treatment strategies and cost, should ideally also be considered in this decision and the identical AMR threshold and recommended treatment regimen(s) may not be the most cost-effective solution in all settings and populations [3, 18, 19].

Current antimicrobial treatment, ceftriaxone treatment failures, ceftriaxone resistant strains, and dual therapy

During the latest decade, cefixime 400 mg × 1 orally or ceftriaxone 125–1000 mg × 1 intramuscularly (IM) or intravenously (IV) has been recommended first-line for monotherapy of gonorrhoea in many countries globally [3–5, 7–9, 18, 20, 21]. However, since the first treatment failures with cefixime were verified in Japan in the early-2000s [22], failures have been verified in many countries worldwide, i.e. Norway, United Kingdom, Austria, France, Canada, and South Africa [23–29]. Most worryingly, sporadic treatment failures with ceftriaxone (250–1000 mg × 1), the last remaining option for empiric first-line monotherapy in many countries, have been verified in Japan, Australia, Sweden, and Slovenia [30–36]. The main characteristics of the verified treatment failures with ceftriaxone (n = 11) are described in Table 1.

Obviously, the number of verified treatment failures with ceftriaxone is low internationally. However, most likely these verified failures only represent the tip of the iceberg, because very few countries have active and quality assured surveillance and appropriately verify treatment failures. It is essential to strengthen this surveillance and follow-up of suspected and verified ceftriaxone treatment failures. WHO publications [2, 9, 16] recommend laboratory parameters to verify treatment failures, which ideally requires examining pre- and post-treatment isolates for ESC MICs, molecular epidemiological genotype, and genetic resistance determinants. Additionally, a detailed clinical history that excludes reinfection and records the treatment regimen(s) used is mandatory.

Briefly, the ceftriaxone MICs of the gonococcal isolates causing the ceftriaxone treatment failures ranged from 0.016 to 4 mg/L. Seven (88 %) of the eight isolates genotyped with multilocus sequence typing (MLST) were assigned to ST1901. Six (55 %) failures were caused by gonococcal strains belonging to the N. gonorrhoeae multiantigen sequence typing (NG-MAST) ST1407 or genetically closely related NG-MAST STs, such as ST2958, ST3149, ST4706, and ST4950, of which five (45 %) belong to NG-MAST genogroup 1407 [37]. However, the failure to treat pharyngeal gonorrhoea in a female commercial sex worker with ceftriaxone 1 g × 1 in Kyoto, Japan, was caused by a strain assigned as MLST ST7363 and NG-MAST ST4220 (Table 1). This strain was the first verified extensively drug-resistant (XDR [9]) N. gonorrhoeae strain (‘H041’; the first gonococcal ‘superbug’), which displayed high-level resistance to ceftriaxone (MIC = 2-4 mg/L) [30]. Only two years later (2011), two additional superbugs were identified in men-who-have-sex-with-men (MSM) in France [26] and Spain [38], which are suspected to belong to the identical strain (‘F89’) and may represent the first international transmission of a high-level ceftriaxone resistant gonococcal strain. In 2014, a ceftriaxone resistant strain with genetic similarities to H041 was reported in Australia [39]. However, this strain had a lower ceftriaxone MIC compared to H041 and F89 (MIC: 0.5 mg/L versus 2–4 mg/L using Etest), and sporadic gonococcal strains with this low-level ceftriaxone resistance have been previously described internationally [25, 40, 41]. The main characteristics of the verified superbugs and examples of sporadic gonococcal strains with ceftriaxone MIC = 0.5 mg/L are described in Table 2.

Briefly, the first verified gonococcal superbug H041 had a ceftriaxone MIC of 4 mg/L using Etest and was assigned to NG-MAST ST4220 and MLST ST7363 [30], an MLST clone that has been prevalent and caused many of the early cefixime treatment failures in Japan. The gonococcal strains causing these early cefixime treatment failures had a mosaic penicillin-binding protein 2 (PBP2) X sequence variant [3, 8, 30, 42–44]. However, H041 had developed also high-level ceftriaxone resistance by 12 additional amino acid alterations in PBP2 X [30], of which the novel key resistance amino acid alterations were A311V, T316P, T483S [45]. The A8806 strain recently detected in Australia (ceftriaxone MIC = 0.5 mg/L) showed some key genetic similarities to H041, including the identical MLST ST7363, similar NG-MAST ST, and shared two (A311V and T483S) of the three PBP2 alterations pivotal to the high-level ceftriaxone resistance [39, 45]. Noteworthy, three of the five additional isolates with ceftriaxone MIC ≥ 0.5 mg/L were assigned as MLST ST1901 and NG-MAST ST1407 (Table 2). This clone has been traced back to 2003 in Japan, accounting for most of the decreased susceptibility and resistance to ESCs in Europe, and basically spread globally [3, 8, 23–27, 29, 32, 35–38, 43, 44, 46, 47]. Noteworthy, although ST1407 has been the most prevalent NG-MAST ST of MLST ST1901 in Europe, many NG-MAST STs of this MLST clone have been identified globally, particularly in Japan, where ST1901 replaced ST7363 as the most prevalent MLST clone already in the early 2000s [3, 8, 43, 44]. Most frequently, this clone has had a mosaic PBP2 XXXIV [3, 8, 23, 27, 35, 36], however, in all these three isolates the PBP2 had mutated and included one additional mutation, i.e., A501P (French and Spanish strain) or T534A (Swedish strain) [25, 26, 38]. Undoubtedly, the superbugs and these additional sporadic strains illustrate that gonococci have different ways to develop ceftriaxone, including high-level, resistance and that only one or a few mutations in PBP2 are required for ceftriaxone resistance in a large proportion of strains circulating worldwide [3, 8, 14, 23–27, 29, 30, 32, 35–40, 42–44, 46–49]. Several additional ceftriaxone resistant strains may already be circulating but are undetected due to the suboptimal AMR surveillance in many settings internationally. Most noteworthy, the gonococcal strain detected in China in 2007 (ceftriaxone MIC = 0.5 mg/L; non-mosaic PBP2 XVII) emphasizes that gonococci can also develop ceftriaxone resistance without a mosaic PBP2 [41]. In the non-mosaic PBP2 XVII, the A501V and G542S mutations are suspected to be involved in the ceftriaxone resistance, i.e. most likely together with the resistance determinants mtrR and penB [3, 8, 41, 45, 50, 51]. Notably, particularly in Asia many strains with a ceftriaxone MIC = 0.25 mg/L, i.e. ceftriaxone resistant according to the European resistance breakpoints (www.eucast.org), which lack a mosaic PBP2 are also circulating. E.g., gonococcal strains with ceftriaxone MIC = 0.25 mg/L and non-mosaic PBP2s have been described in China (PBP2 XIII with A501TV and P551S [41]), South Korea (PBP2 IV and V with G542S [48], and XIII with A501TV and P551S [49]), and Vietnam (PBP2 XVIII with A501T and G542S [51]).

Regarding pharmacodynamics, it has been suggested that a time of free ESC above MIC (fT>MIC) of 20–24 hours is required for treatment with ESCs [52]. Applying these figures on the gonococcal superbugs and other sporadic strains with ceftriaxone MICs ≥ 0.5 mg/L, according to Monte Carlo simulations sufficient fT>MIC is not reached for any strain even at upper 95 % confidence interval (CI) when using ceftriaxone 250 mg × 1. Furthermore, even with ceftriaxone 1 g × 1, 20–24 hours of fT>MIC will be reached in only very few, if any, patients infected with the superbugs and additionally it will not be reached in many of the patients infected even with the strains showing ceftriaxone MIC = 0.5 mg/L (Table 2). However, several of the ceftriaxone treatment failures have been caused by ceftriaxone susceptible gonococcal strains with a relatively low ceftriaxone MIC (0.016-0.125 mg/L), and in many of these cases the fT>MIC should have been substantially longer than 20–24 hours (Table 1). These treatment failures were all for pharyngeal gonorrhoea and, most likely, reflect the difficulties in treating pharyngeal gonorrhoea compared with urogenital gonorrhoea [3, 8, 9, 13, 30–36, 53–55]. Sufficient understanding regarding the complex process when antimicrobials penetrate into the pharyngeal mucosa, where also the presence of inflammation and pharmacokinetic properties of the antimicrobial are important factors, is lacking. It is crucial to elucidate why many antimicrobials, at least in some patients, appear to achieve suboptimal concentrations in tonsillar and other oropharyngeal tissues [55]. Appropriate pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies and/or optimized simulations with currently and futurely used antimicrobials are essential for gonorrhoea, particularly pharyngeal infection. It has also been suggested that ESC resistance initially emerged in commensal Neisseria spp., which act as a reservoir of AMR genes that are easily transferred to gonococci through transformation, particularly in pharyngeal gonorrhoea [3, 7–9, 42, 55–57]. Pharyngeal gonorrhoea is mostly asymptomatic, and gonococci and commensal Neisseria spp. can coexist for long time periods in the pharynx and share AMR genes and other genetic material. Accordingly, an enhanced focus on early detection (screening of high-risk populations, such as MSM, with nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) should be considered) and appropriate treatment of pharyngeal gonorrhoea is imperative [2,3,8,13,56,].

The emergence of ceftriaxone treatment failures and particularly the superbugs with high-level ceftriaxone resistance [26, 30, 38], combined with resistance to mainly all other gonorrhoea antimicrobials, resulted in a fear that gonorrhoea might become exceedingly-difficult-to-treat or even untreatable. Consequently, the WHO published the ‘Global Action Plan to Control the Spread and Impact of Antimicrobial Resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae’ [2, 58], and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) [59] and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published region-specific response plans [60]. In general, all these plans request more holistic actions, i.e., to improve early prevention, diagnosis, contact tracing, treatment, including test-of-cure, and epidemiological surveillance of gonorrhoea cases. It was also stated essential to, nationally and internationally, significantly enhance the surveillance of AMR (maintaining culture is imperative), treatment failures and antimicrobial use/misuse locally (strong antimicrobial stewardship crucial). Evidently, gonococcal AMR data were lacking in many settings globally and, accordingly, the WHO Global Gonococcal Antimicrobial Surveillance Programme (WHO Global GASP) was reinitiated in 2009, in close liaison with other AMR surveillance initiatives, to enable a coordinated global response [58]. During recent years, dual antimicrobial therapy (mainly ceftriaxone 250–500 mg × 1 and azithromycin 1–2 g × 1) for empirical gonorrhoea treatment has also been introduced in Europe, Australia, USA, Canada, and some additional countries (Table 3).

Briefly, all regions or countries, with exception of Canada, recommend only ceftriaxone plus azithromycin as first-line [61–66]. However, the recommended doses of ceftriaxone vary, i.e. range from 250 mg × 1 (USA and Canada) to 1 g × 1 (Germany), and the doses of azithromycin range from 1 g × 1 (USA, Canada, UK and Australia) to 2 g × 1 (Europe) (Table 3). Appropriate clinical data to support the different recommended doses of ceftriaxone and azithromycin (in the combination therapy) for the currently circulating gonococcal population are mainly lacking. Instead, these treatment regimens were based on early clinical efficacy trials [3, 7, 54, 67–72], pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic simulations [52], in vitro AMR surveillance data, anticipated trends in AMR, case reports of treatment failures [22–26, 30, 31, 34, 36, 73], and expert consultations. No other currently available and evaluated injectable cephalosporin (e.g., ceftizoxime, cefoxitin with probenecid, and cefotaxime) offers any advantages over ceftriaxone in terms of efficacy and pharmokinetics/pharmacodynamics, and efficacy for pharyngeal infection is less certain [3, 8, 9, 21, 61, 65, 67–72, 74]. In Canada, also an oral first-line therapy is recommended, i.e. cefixime 800 mg × 1 plus azithromycin 1 g × 1. Mainly early evidence indicated that cefixime 800 mg × 1 was safe and effective in treating gonorrhoea [66, 69, 71, 72, 75, 76]. Pharmacodynamic studies and/or simulations have also shown that, compared to 400 mg × 1, 800 mg of cefixime (particularly administered as 400 mg × 2, 6 hours apart) substantially increases the fT>MIC of cefixime [22, 52]. However, in most countries cefixime is only licensed for the currently or previously used 400 mg × 1, due to the more frequent gastrointestinal adverse effects observed with 800 mg × 1 [70], and treatment failures with also cefixime 800 mg × 1 have been verified [28].

Two different novel dual antimicrobial regimens have also been evaluated for treatment of uncomplicated urogenital gonorrhoea, i.e., gentamicin (240 mg × 1 IM) plus azithromycin (2 g × 1 orally), and gemifloxacin (320 mg × 1 orally) plus azithromycin (2 g × 1 orally) [77]. The cure rate was 100 % with gentamicin + azithromycin and 99.5 % with gemifloxacin + azithromycin, but gastrointestinal adverse effects were frequent. E.g., 3.3 % and 7.7 % of patients, respectively, vomited within one hour of treatment, which necessitated retreatment with ceftriaxone and azithromycin [77]. Nevertheless, these two therapeutic regimens can be considered in the presence of ceftriaxone resistance, treatment failure with recommended regimen, or ESC allergy.

Future treatment of gonorrhoea

Future treatment should be in strict concordance with continuously updated evidence-based management guidelines, informed by quality assured surveillance of local AMR and also treatment failures. Dual antimicrobial therapy (ceftriaxone and azithromycin [61–66]), which also eradicates concurrent chlamydial infections and many concurrent Mycoplasma genitalium infections, should be considered in all settings where local quality assured AMR data do not support other therapeutic options. Despite that the dual antimicrobial regimens with ceftriaxone and azithromycin may not entirely prevent resistance emergence [3, 8, 78], they will mitigate the spread of resistant strains. Nevertheless, after strict evaluation (effectiveness and compliance) multiple doses of single antimicrobials should also be considered. An oral treatment regimen (single or dual antimicrobials) would be exceedingly valuable and also allow patient-delivered partner therapy that at least in some settings may decrease the gonorrhoea prevalence at population level [79, 80].

Ideally, treatment at first health care visit will also be individually-tailored, i.e. by novel rapid phenotypic AMR tests, e.g. broth microdilution MIC assays, or genetic point of care (POC) AMR tests, including detection of gonococci. This will ensure a rational antimicrobial use (including sparing last-line antimicrobials), timely notification of sexual contacts, slow the AMR development, and improve the public health control of both gonorrhoea and AMR [3, 4, 6, 81, 82]. No commercially available gonococcal NAAT detects any AMR determinants. However, laboratory-developed NAATs have been designed and used for identification of genetic AMR determinants involved in resistance to penicillins, tetracyclines, macrolides, fluoroquinolones, cephalosporins, and multidrug-resistance [3–7, 83–87]. Some “strain-specific” NAATs detecting the key ESC resistance mutations in the superbugs H041 [30] and F89 [26, 38] have also been developed [88, 89]. However, genetic AMR testing will not entirely replace phenotypic AMR testing because the relationships between phenotypes and genotypes are not ideal, genetic methods can only identify known AMR determinants, the sensitivity and/or specificity in the prediction of AMR or antimicrobial susceptibility is suboptimal (particularly for ESCs with their ongoing resistance evolution involving many different genes, mutations, and their epistasis), and new AMR determinants continuously evolve [3–5, 8, 14]. Tests requiring continual updating with new targets will not be profitable for commercial companies manufacturing NAATs. In addition, several of the gonococcal AMR determinants, e.g. mosaic penA alleles, originate in commensal Neisseria species, which makes it difficult to predict gonococcal AMR in pharyngeal samples [3, 8, 9]. Further research is crucial to continuously identify new AMR determinants and appropriately evaluate how current and future molecular AMR assays can supplement phenotypic AMR surveillance and ultimately guide individually-tailored treatment [3, 4, 6, 8, 14]. At present, at least for AMR surveillance ciprofloxacin susceptibility is relatively easy to predict, azithromycin susceptibility or resistance can be indicated, and decreased susceptibility or resistance to ESCs can be predicted, although with a low specificity, by detecting mosaic penA alleles. Nevertheless, also non-mosaic PBP2 sequences can cause ceftriaxone resistance [41, 48, 49, 51]. High-throughput genome sequencing [46, 47, 90–92], transcriptomics and other novel technologies will likely revolutionize the genetic AMR prediction and molecular epidemiological investigations of both gonococcal isolates and gonococcal NAAT positive samples.

Future treatment options for gonorrhoea

The current dual antimicrobial treatment regimens (ceftriaxone plus azithromycin [61–66]) appear to be effective. However, the susceptibility to ceftriaxone in gonococci has decreased globally, azithromycin resistance is relatively prevalent in many countries, concomitant resistance to ceftriaxone and azithromycin has been identified in several countries, and the dual antimicrobial regimens are not affordable in many less-resourced settings [3, 8, 14, 15, 18, 78]. Furthermore, treatment failures with even azithromycin 2 g × 1 have been verified [93–95] and gonococcal strains with high-level resistance to azithromycin (MIC ≥ 256 mg/L) have been described in Scotland [96], United Kingdom [97], Ireland [98], Italy [99], Sweden [100], USA [101], Argentina [102], and Australia [103]. Accordingly, no treatment failure with dual antimicrobial therapy (ceftriaxone 250–500 mg × 1 plus azithromycin 1–2 g × 1) has been verified yet, nevertheless, most likely it is only a matter of when, and not if, treatment failures with these dual antimicrobial regimens will emerge. Consequently, novel affordable antimicrobials for monotherapy or at least inclusion in new dual treatment regimens for gonorrhoea, which might need to be considered for all newly designed antimicrobials, are essential.

The earlier frequently used aminocyclitol spectinomycin (2 g × 1 IM) is effective for treatment of anogenital gonorrhoea, however, the efficacy against pharyngeal infection is low (51.8 %; 95 %CI: 38.7 %-64.9 %) [53] and it is currently not available in many countries [3, 61, 62, 65]. However, the in vitro susceptibility to spectinomycin is exceedingly high worldwide, including in South Korea where it has been very frequently used for treatment [3, 5, 7, 8, 18, 49, 51, 61, 104–109]. Accordingly, in South Korea 53-58 % of gonorrhoea patients in 2002–2006 [109] and 52-73 % in 2009–2012 were treated with spectinomycin [49]. Despite this exceedingly high spectinomycin usage, spectinomycin resistance has not been reported since 1993 in South Korea [49]. Thus, the spread of spectinomycin resistance in the 1980s [110–112] may reflect more uncontrolled usage of spectinomycin and the transmission of some few successful spectinomycin resistant gonococcal strains. Research regarding biological fitness cost of spectinomycin resistance would be valuable, and in fact spectinomycin might be underestimated for treatment of gonorrhoea. This is particularly in dual antimicrobial therapy together with azithromycin 1–2 g × 1, which are alternative therapeutic regimens recommended in the European [61] and Canadian [66] gonorrhoea management guidelines, that will also cover pharyngeal gonorrhoea and potentially mitigate emergence of resistance to both spectinmycin and azithromycin.

Other “old” antimicrobials that have been suggested for future empirical monotherapy of gonorrhoea include the injectable carbapenem ertapenem [113, 114], oral fosfomycin [115], and injectable aminoglycoside gentamicin, which has been used as first-line treatment, 240 mg × 1 IM together with doxycycline in syndromic management, in Malawi since 1993 without any reported emergence of in vitro resistance [3, 7, 61, 65, 67, 77, 116–119]. However, disadvantages with these antimicrobials include that in vitro resistance is rapidly selected (fosfomycin) or decreased susceptibility already exist (ertapenem [113, 114]), evidence-based correlates between MICs, pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters and gonorrhoea treatment outcome are lacking (gentamicin, fosfomycin and ertapenem), and mainly no recent clinical data exist for empiric monotherapy of urogenital and particularly extragenital gonorrhoea (gentamicin, fosfomycin and ertapenem). Consequently, these antimicrobials are most likely mainly options for ceftriaxone-resistant gonorrhoea, ESC allergy and/or in noval dual antimicrobial treatment regimens. Nevertheless, some small observational or controlled studies mainly from the 1970s and 1980s evaluated gentamicin for monotherapy of gonorrhoea. Two recent meta-analyses of several of these studies reported that a single dose of gentamicin resulted in cure rates of only 62-98 % [119] and a pooled cure rate of 91.5 % (95 %CI: 88-94 %) [118]. However, these early gentamicin studies were mainly small, of low quality and in general provided insufficient data. Consequently, a multi-centre (n = 8), parallel group, investigator-blinded, non-inferiority, randomized, controlled Phase 3 clinical trial has been recently initiated. This study aims to recruit 720 patients with uncomplicated urogenital, pharyngeal and rectal gonorrhoea. Treatment with gentamicin 240 mg × 1 IM (n = 360) compared to ceftriaxone 500 mg × 1 IM (n = 360), plus azithromycin 1 g × 1 orally to each arm, will be evaluated, in regard to clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and safety (www.research.uhb.nhs.uk/gtog).

Many derivates of earlier used antimicrobials have also been evaluated in vitro against gonococcal strains recent years. For example, several new fluoroquinolones, e.g. avarofloxacin (JNJ-Q2), sitafloxacin, WQ-3810, and delafloxacin, have shown relatively high potency against gonococci, including ciprofloxacin-resistant isolates [120–123]. The fluorocycline eravacycline (TP-434) and glycylcycline tigecycline (family: tetracyclines) also appear to be effective against gonococci [124, 125]. Nevertheless, a small fraction of administered tigecycline is excreted unchanged in urine, which might question the use in gonorrhoea treatment [126–128]. The lipoglycopeptide dalbavancin and two new 2-acyl carbapenems (SM-295291 and SM-369926) have shown a high activity against a limited number of gonococcal isolates [129, 130]. Finally, the two “bicyclic macrolides” modithromycin (EDP-420) and EDP-322 displayed relatively high activity against azithromycin-resistant, ESC-resistant and multidrug-resistant (MDR) gonococci, but high-level azithromycin resistant gonococcal isolates (MIC ≥ 256 mg/L) were resistant also to modithromycin and EDP-322 [131]. Unfortunately, no clinical efficacy data for treatment of gonorrhoea exist for any of these antimicrobials. More advanced in the development is the novel oral fluoroketolide solithromycin (family: macrolides) that has proved to have a high activity against gonococci, including azithromycin-resistant, ESC-resistant and MDR isolates [132]. Solithromycin has three binding sites on the bacterial ribosome (compared with two for other macrolides), which likely result in a higher antibacterial activity and delay resistance emergence [133]. However, gonococcal strains with high-level azithromycin resistance (MIC ≥ 256 mg/L) appear to be resistant also to solithromycin (MICs = 4-32 mg/L) [132]. Solithromycin is well absorbed orally, with high plasma levels, intracellular concentrations and tissue distribution, has a long post-antimicrobial effect, and a 1.6 g × 1 oral dose is well-tolerated [134]. A minor Phase 2 single-center, open-label study showed that solithromycin (1.2 g × 1) treated all 22 evaluable patients with uncomplicated urogenital gonorrhoea [135]. An open-label, randomized, multi-centre Phase 3 clinical trial is currently recruiting participants with uncomplicated urogenital gonorrhoea. The study aims to include 300 participants and solithromycin 1 g × 1 orally will be compared to a dual antimicrobial regimen, i.e. ceftriaxone 500 mg × 1 plus azithromycin 1 g × 1 (www.clinicaltrials.gov).

Despite that derivates of “old” antimicrobials are developed, it is essential to develop novel antimicrobial targets, compounds and treatment strategies. Drugs with multiple targets might be crucial to mitigate resistance emergence. Recent years, several antimicrobials or other compounds, using new targets or antibacterial strategies, have been developed and shown a potent in vitro activity against gonococcal isolates. E.g., new protein synthesis inhibitors such as pleuromutilin BC-3781 and the boron-containing inhibitor AN3365; LpxC inhibitors; species-specific FabI inhibitors such as MUT056399; and novel bacterial topoisomerase inhibitors with target(s) different from the fluoroquinolones such as VXc-486 (also known as VT12-008911) and ETX0914 (also known as AZD0914) [136–143]. The novel oral spiropyrimidinetrione ETX0914, which additionally has a new mode-of-action [144, 145], is most advanced in the development. No resistance was initially observed examining 250 temporally, geographically and genetically diverse isolates including many fluoroquinolone-, ESC- and multidrug-resistant isolates [141]. Recently, it was shown that the susceptibility to ETX0914 among 873 contemporary clinical isolates from 21 European countries was high and no resistance was indicated [143]. ETX0914 administered orally has good target tissue penetrance, good bioavailability, high safety and tolerability (200–4000 mg × 1 orally well tolerated in healthy adult subjects in both fed and fasted state) as indicated from initial animal toxicology study and Phase 1, randomized, placebo-controlled trial conducted in 48 healthy subjects [146, 147]. An open-label, randomized, multi-centre Phase 2 clinical trial is currently recruiting patients with uncomplicated urogenital gonorrhoea. The study aims to include 180 participants and treatment with ETX0914 2 g orally (n = 70) and ETX0914 3 g orally (n = 70) will be evaluated against ceftriaxone 500 mg (n = 40) (www.clinicaltrials.gov).

Conclusions

Dual antimicrobial therapy of gonorrhoea (ceftriaxone 250 mg-1 g plus azithromycin 1–2 g [61–66]) appears currently effective and should be considered in all settings where local quality assured AMR data do not support other therapeutic options. These dual antimicrobial regimens may not entirely prevent resistance emergence in gonococci [3, 8, 78], but they will mitigate the spread of resistant strains. Unfortunately, the first failure with dual antimicrobial therapy will most likely soon be verified. Novel affordable antimicrobials for monotherapy or at least inclusion in new dual treatment regimens for gonorrhoea are essential and several of the recently developed antimicrobials deserve increased attention. In vitro activity studies examining collections of geographically, temporally and genetically diverse gonococcal isolates, including MDR strains, particularly with ESC resistance and azithromycin resistance are important. Furthermore, knowledge regarding effects and biological fitness of current and emerging (in vitro selected and in vivo emerged) genetic resistance mechanisms for these antimicrobials, prediction of resistance emergence, time-kill curve analysis to evaluate antibacterial activity, and correlates between genetic and phenotypic laboratory parameters, and clinical treatment outcomes, would also be valuable. Subsequently, appropriately designed, randomized and controlled clinical trials evaluating efficacy, ideal dose, adverse effects, cost, and pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamics data for anogenital and, importantly, also pharyngeal gonorrhoea, i.e. because treatment failures initially emerge at this anatomical site, are crucial. Finally, several examples of “thinking out of the box” for future management of gonorrhoea have also been developed recently [3] and now is certainly the right time to readdress the challenges of developing a gonococcal vaccine [148].

Abbreviations

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- AMR:

-

Antimicrobial resistance

- IM:

-

Intramuscularly

- IV:

-

Intravenously

- MIC:

-

Minimum inhibitory concentration

- fT>MIC:

-

Simulation of time of free ceftriaxone above MIC

- MLST:

-

Multilocus sequence typing

- NG-MAST:

-

N. gonorrhoeae multi-antigen sequence typing

- ND:

-

Not determined

- ST:

-

Sequence type

- XDR:

-

Extensively drug-resistant

- MSM:

-

Men-who-have-sex-with-men

- PBP2:

-

Penicillin-binding protein 2

- NAAT:

-

Nucleic acid amplification test

- ECDC:

-

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control

- CDC:

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- POC:

-

Point of care

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- MDR:

-

Multidrug resistance

- STI:

-

Sexually transmitted infection

References

World Health Organization (WHO). Global incidence and prevalence of selected curable sexually transmitted infections - 2008. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. p. 2012.

World Health Organization (WHO). Department of Reproductive Health and Research. 2012. Global action plan to control the spread and impact of antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Geneva: WHO; 2012. p. 1–36.

Unemo M, Shafer WM. Antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the 21st Century: past, evolution, and future. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:587–613.

Buono SA, Watson TD, Borenstein LA, Klausner JD, Pandori MW, Godwin HA. Stemming the tide of drug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae: the need for an individualized approach to treatment. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:374–81.

Unemo M, Shafer WM. Antibiotic resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: origin, evolution, and lessons learned for the future. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1230:E19–28.

Goire N, Lahra MM, Chen M, Donovan B, Fairley CK, Guy R, et al. Molecular approaches to enhance surveillance of gonococcal antimicrobial resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12:223–9.

Lewis DA. 2010. The gonococcus fights back: is this time a knock out? Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86:415–21.

Unemo M, Nicholas RA. Emergence of multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and untreatable gonorrhea. Future Microbiol. 2012;7:1401–22.

Tapsall JW, Ndowa F, Lewis DA, Unemo M. Meeting the public health challenge of multidrug- and extensively drug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2009;7:821–34.

Bolan GA, Sparling PF, Wasserheit JN. The emerging threat of untreatable gonococcal infection. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:485–7.

Ison CA. Antimicrobial resistance in sexually transmitted infections in the developed world: implications for rational treatment. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2012;25:73–8.

Whiley DM, Goire N, Lahra MM, Donovan B, Limnios AE, Nissen MD, et al. The ticking time bomb: escalating antibiotic resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae is a public health disaster in waiting. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:2059–61.

Barbee LA. Preparing for an era of untreatable gonorrhea. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2014;27:282–7.

Whiley DM, Lahra MM, Unemo M. Prospects of untreatable gonorrhea and ways forward. Future Microbiol. 2015;10:313–6.

Unemo M, Shafer WM. Future treatment of gonorrhoea - novel emerging drugs are essential and in progress? Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2015;24:1–4.

World Health Organization (WHO). Strategies and laboratory methods for strengthening surveillance of sexually transmitted infections. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75729/1/9789241504478_eng.pdf (11 June 2015, date last accessed).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Antibiotic-resistant strains of Neisseria gonorrhoeae: policy guidelines for detection, management and control. MMWR. 1987;36(Suppl 5S):13S.

Ison CA, Deal C, Unemo M. Current and future treatment options for gonorrhoea. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89 Suppl 4:iv52–6.

Roy K, Wang SA, Meltzer MI. Optimizing treatment of antimicrobial-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1265–73.

Unemo M, Shipitsyna E. Domeika M; on behalf of the Eastern European Sexual and Reproductive Health (EE SRH) Network Antimicrobial Resistance Group. Recommended antimicrobial treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhoea in 2009 in 11 East European countries: implementation of a Neisseria gonorrhoeae antimicrobial susceptibility programme in this region is crucial. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86:442–4.

Tapsall JW. Implications of current recommendations for third-generation cephalosporin use in the WHO Western Pacific Region following the emergence of multiresistant gonococci. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85:256–8.

Deguchi T, Yasuda M, Yokoi S, Ishida K, Ito M, Ishihara S, et al. Treatment of uncomplicated gonococcal urethritis by double-dosing of 200 mg cefixime at a 6-h interval. J Infect Chemother. 2003;9:35–9.

Unemo M, Golparian D, Syversen G, Vestrheim DF, Moi H. Two cases of verified clinical failures using internationally recommended first-line cefixime for gonorrhoea treatment, Norway, 2010. Euro Surveill. 2010;15(47)

Ison CA, Hussey J, Sankar KN, Evans J, Alexander S. Gonorrhoea treatment failures to cefixime and azithromycin in England. Euro Surveill. 2011;16(14)

Unemo M, Golparian D, Stary A, Eigentler A. First Neisseria gonorrhoeae strain with resistance to cefixime causing gonorrhoea treatment failure in Austria, 2011. Euro Surveill. 2011;16(43)

Unemo M, Golparian D, Nicholas R, Ohnishi M, Gallay A, Sednaoui P. High-level cefixime- and ceftriaxone-resistant N. gonorrhoeae in France: novel penA mosaic allele in a successful international clone causes treatment failure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:1273–80.

Allen VG, Mitterni L, Seah C, Rebbapragada A, Martin IE, Lee C, et al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae treatment failure and susceptibility to cefixime in Toronto. Canada JAMA. 2013;309:163–70.

Singh AE, Gratrix J, Martin I, Friedman DS, Hoang L, Lester R, et al. Gonorrhea treatment failures with oral and injectable expanded spectrum cephalosporin monotherapy vs dual therapy at 4 Canadian sexually transmitted infection clinics, 2010–2013. Sex Transm Dis. 2015;42:331–6.

Lewis DA, Sriruttan C, Müller EE, Golparian D, Gumede L, Fick D, et al. Phenotypic and genetic characterization of the first two cases of extended-spectrum cephalosporin resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection in South Africa and association with cefixime treatment failure. J Antimicrobial Chemother. 2013;68:1267–70.

Ohnishi M, Golparian D, Shimuta K, Saika T, Hoshina S, Iwasaku K, et al. Is Neisseria gonorrhoeae initiating a future era of untreatable gonorrhea? Detailed characterization of the first strain with high-level resistance to ceftriaxone. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:3538–45.

Tapsall J, Read P, Carmody C, Bourne C, Ray S, Limnios A, et al. Two cases of failed ceftriaxone treatment in pharyngeal gonorrhoea verified by molecular microbiological methods. J Med Microbiol. 2009;58:683–7.

Chen YM, Stevens K, Tideman R, Zaia A, Tomita T, Fairley CK, et al. Failure of ceftriaxone 500 mg to eradicate pharyngeal gonorrhoea, Australia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:1445–7.

Read PJ, Limnios EA, McNulty A, Whiley D, Lahra LM. One confirmed and one suspected case of pharyngeal gonorrhoea treatment failure following 500 mg ceftriaxone in Sydney. Australia Sex Health. 2013;10:460–2.

Unemo M, Golparian D, Hestner A. Ceftriaxone treatment failure of pharyngeal gonorrhoea verified by international recommendations, Sweden, July 2010. Euro Surveill. 2011;16:1–3.

Golparian D, Ohlsson A, Janson H, Lidbrink P, Richtner T, Ekelund O, et al. Four treatment failures of pharyngeal gonorrhoea with ceftriaxone (500 mg) or cefotaxime (500 mg), Sweden, 2013 and 2014. Euro Surveill. 2014;19

Unemo M, Golparian D, Potočnik M, Jeverica S. Treatment failure of pharyngeal gonorrhoea with internationally recommended first-line ceftriaxone verified in Slovenia, September 2011. Euro Surveill. 2012;17:1–4.

Chisholm SA, Unemo M, Quaye N, Johansson E, Cole MJ, Ison CA, Van de Laar MJ. Molecular epidemiological typing within the European Gonococcal Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Programme reveals predominance of a multidrug-resistant clone. Euro Surveill. 2013;18.

Cámara J, Serra J, Ayats J, Bastida T, Carnicer-Pont D, Andreu A, et al. Molecular characterization of two high-level ceftriaxone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates detected in Catalonia, Spain. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:1858–60.

Lahra MM, Ryder N, Whiley DM. A new multidrug-resistant strain of Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Australia. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1850–1.

Tanaka M, Nakayama H, Huruya K, Konomi I, Irie S, Kanayama A, et al. Analysis of mutations within multiple genes associated with resistance in a clinical isolate of Neisseria gonorrhoeae with reduced ceftriaxone susceptibility that shows a multidrug-resistant phenotype. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2006;27:20–6.

Chen SC, Yin YP, Dai XQ, Unemo M, Chen XS. Antimicrobial resistance, genetic resistance determinants for ceftriaxone and molecular epidemiology of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates in Nanjing. China J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:2959–65.

Ohnishi M, Watanabe Y, Ono E, Takahashi C, Oya H, Kuroki T, et al. Spreading of a chromosomal cefixime-resistant penA gene among different Neisseria gonorrhoeae lineages. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:1060–7.

Shimuta K, Unemo M, Nakayama S, Morita-Ishihara T, Dorin M, Kawahata T, et al. Antimicrobial resistance and molecular typing of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates in Kyoto and Osaka, Japan, 2010 to 2012: intensified surveillance after identification of the first strain (H041) with high-level ceftriaxone resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:5225–32.

Shimuta K, Watanabe Y, Nakayama S-I, Morita-Ishihara T, Kuroki T, Unemo M, et al. Emergence and evolution of internationally disseminated cephalosporin-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae clones from 1995 to 2005 in Japan. BMC Infect Dis. In press.

Tomberg J, Unemo M, Ohnishi M, Davies C, Nicholas RA. Identification of the amino acids conferring high-level resistance to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins in the penA gene from the Neisseria gonorrhoeae strain H041. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:3029–36.

Grad YH, Kirkcaldy RD, Trees D, Dordel J, Harris SR, Goldstein E, et al. Genomic epidemiology of Neisseria gonorrhoeae with reduced susceptibility to cefixime in the USA: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:220–6.

Demczuk W, Lynch T, Martin I, Van Domselaar G, Graham M, Bharat A, et al. Whole-genome phylogenomic heterogeneity of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates with decreased cephalosporin susceptibility collected in Canada between 1989 and 2013. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:191–200.

Lee SG, Lee H, Jeong SH, Yong D, Chung GT, Lee YS, et al. Various penA mutations together with mtrR, porB and ponA mutations in Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates with reduced susceptibility to cefixime or ceftriaxone. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:669–75.

Lee H, Unemo M, Kim HJ, Seo Y, Lee K, Chong Y. Emergence of decreased susceptibility and resistance to extended-spectrum cephalosporins in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Korea. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015 june 17. [Epub ahead of print].

Whiley DM, Goire N, Lambert SB, Ray S, Limnios EA, Nissen MD, et al. Reduced susceptibility to ceftriaxone in Neisseria gonorrhoeae is associated with mutations G542S, P551S and P551L in the gonococcal penicillin-binding protein 2. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:1615–8.

Olsen B, Pham TL, Golparian D, Johansson E, Tran HK, Unemo M. Antimicrobial susceptibility and genetic characteristics of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates from Vietnam, 2011. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:40.

Chisholm SA, Mouton JW, Lewis DA, Nichols T, Ison CA, Livermore DM. Cephalosporin MIC creep among gonococci: time for a pharmacodynamic rethink? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:2141–8.

Moran JS. Treating uncomplicated Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections: is the anatomic site of infection important? Sex Transm Dis. 1995;22:39–47.

Moran JS, Levine WC. Drugs of choice for the treatment of uncomplicated gonococcal infections. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20 Suppl 1:S47–65.

Lewis DA. Will targeting oropharyngeal gonorrhoea delay the further emergence of drug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains? Sex Transm Infect. 2015;91:234–7.

Furuya R, Onoye Y, Kanayama A, Saika T, Iyoda T, Tatewaki M, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in clinical isolates of Neisseria subflava from the oral cavities of a Japanese population. J Infect Chemother. 2007;13:302–4.

Saika T, Nishiyama T, Kanayama A, Kobayashi I, Nakayama H, Tanaka M, et al. Comparison of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates from the genital tract and pharynx of two gonorrhea patients. J Infect Chemother. 2001;7:175–9.

Ndowa F, Lusti-Narasimhan M, Unemo M. The serious threat of multidrug-resistant and untreatable gonorrhoea: the pressing need for global action to control the spread of antimicrobial resistance, and mitigate the impact on sexual and reproductive health. Sex Transm Infect. 2012;88:317–8.

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Response plan to control and manage the threat of multidrug-resistant gonorrhoea in Europe. Stockholm: ECDC; 2012. p. 1–23. www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/1206-ECDC-MDR-gonorrhoea-response-plan.pdf (11 June 2015, date last accessed).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Cephalosporin-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae public health response plan. 2012. p. 1–43. http://www.cdc.gov/std/gonorrhea/default.htm (11 June 2015, date last accessed).

Bignell C, Unemo M. 2012 European guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of gonorrhoea in adults. Int J STD AIDS. 2013;24:85–92.

Bignell C, Fitzgerald M. UK national guideline for the management of gonorrhoea in adults, 2011. Int J STD AIDS. 2011;22:541–7.

AWMF-Register. Nr. 059/004 – S2k-Leitlinie: Gonorrhoe bei Erwachsenen und Adoleszenten aktueller Stand: 08/2013. 1–31 [In German].

Australasian Sexual Health Alliance (ASHA). Australian STI Management Guidelines for Use in Primary Care. www.sti.guidelines.org.au/sexually-transmissible-infections/gonorrhoea#management (11 June 2015, date last accessed).

Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(RR-03):1–137.

Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Guidelines on Sexually Transmitted Infections. Gonococcal Infections Chapter. 2013. www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/std-mts/sti-its/cgsti-ldcits/assets/pdf/section-5-6-eng.pdf (11 June 2015, date last accessed).

Newman LM, Moran JS, Workowski KA. Update on the management of gonorrhea in adults in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44 Suppl 3:S84–S101.

Barry PM, Klausner JD. The use of cephalosporins for gonorrhea: the impending problem of resistance. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2009;10:555–77.

Handsfield HH, Dalu ZA, Martin DH, Douglas Jr JM, McCarty JM, Schlossberg D. Multicenter trial of single-dose azithromycin vs ceftriaxone in the treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhoea. Sex Transm Dis. 1994;21:107–11.

Handsfield HH, McCormack WM, Hook 3rd EW, Douglas Jr JM, Covino JM, Verdon MS, et al. A comparison of single-dose cefixime with ceftriaxone as treatment for uncomplicated gonorrhea. The Gonorrhea Treatment Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1337–41.

Bai ZG, Bao XJ, Cheng WD, Yang KH, Li YP. Efficacy and safety of ceftriaxone for uncomplicated gonorrhoea: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J STD AIDS. 2012;23:126–32.

Portilla I, Lutz B, Montalvo M, Mogabgab WJ. Oral cefixime versus intramuscular ceftriaxone in patients with uncomplicated gonococcal infections. Sex Transm Dis. 1992;19:94–8.

Yokoi S, Deguchi T, Ozawa T, Yasuda M, Ito S, Kubota Y, et al. Threat to cefixime treatment for gonorrhea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1275–7.

Ison CA, Mouton JW, Jones K, Fenton KA, Livermore DM. Which cephalosporin for gonorrhoea? Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80:386–8.

Megran DW, Lefebvre K, Willetts V, Bowie WR. Single-dose oral cefixime versus amoxicillin plus probenicid for the treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhea in men. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:355–7.

Dunnett DM, Moyer MA. Cefixime in the treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhea. Sex Transm Dis. 1992;19:92–3.

Kirkcaldy RD, Weinstock HS, Moore PC, Philip SS, Wiesenfeld HC, Papp JR, et al. The efficacy and safety of gentamicin plus azithromycin and gemifloxacin plus azithromycin as treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:1083–91.

Rice LB. Will use of combination cephalosporin/azithromycin therapy forestall resistance to cephalosporins in Neisseria gonorrhoeae? Sex Transm Infect. 2015;91:238–40.

Golden MR, Kerani RP, Stenger M, Hughes JP, Aubin M, Malinski C, et al. Uptake and population-level impact of expedited partner therapy (EPT) on Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae: the Washington State community-level randomized trial of EPT. PLoS Med. 2015;12(1):e1001777.

Golden MR, Barbee LA, Kerani R, Dombrowski JC. Potential deleterious effects of promoting the use of ceftriaxone in the treatment of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Sex Transm Dis. 2014;41:619–25.

Low N, Unemo M, Jensen JS, Breuer J, Stephenson JM. Molecular diagnostics for gonorrhoea: implications for antimicrobial resistance and the threat of untreatable gonorrhoea. PLOS Med. 2014;11:e1001598.

Sadiq ST, Dave J, Butcher PD. Point-of-care antibiotic susceptibility testing for gonorrhoea: improving therapeutic options and sparing the use of cephalosporins. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86:445–6.

Peterson SW, Martin I, Demczuk W, Bharat A, Hoang L, Wylie J, et al. Molecular assay for the detection of genetic markers associated with decreased susceptibility to cephalosporins in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Clin Microbiol. 2015 Apr 15. [Epub ahead of print].

Gose S, Nguyen D, Lowenberg D, Samuel M, Bauer H, Pandori M. Neisseria gonorrhoeae and extended-spectrum cephalosporins in California: surveillance and molecular detection of mosaic penA. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:570.

Nicol M, Whiley D, Nulsen M, Bromhead C. Direct detection of markers associated with Neisseria gonorrhoeae antimicrobial resistance in New Zealand using residual DNA from the Cobas 4800 CT/NG NAAT assay. Sex Transm Infect. 2015;91:91–3.

Speers DJ, Fisk RE, Goire N, Mak DB. Non-culture Neisseria gonorrhoeae molecular penicillinase production surveillance demonstrates the long-term success of empirical dual therapy and informs gonorrhoea management guidelines in a highly endemic setting. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:1243–7.

Buckley C, Trembizki E, Baird RW, Chen M, Donovan B, Freeman K, et al. A multi-target PCR for direct detection of penicillinase-producing Neisseria gonorrhoeae for enhanced surveillance of gonococcal antimicrobial resistance. J Clin Microbiol. 2015 May 20. [Epub ahead of print].

Goire N, Ohnishi M, Limnios AE, Lahra MM, Lambert SB, Nimmo GR, et al. Enhanced gonococcal antimicrobial surveillance in the era of ceftriaxone resistance: a real-time PCR assay for direct detection of the Neisseria gonorrhoeae H041 strain. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:902–5.

Goire N, Lahra MM, Ohnishi M, Hogan T, Liminios AE, Nissen MD, et al. Polymerase chain reaction-based screening for the ceftriaxone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae F89 strain. Euro Surveill. 2013;18:20444.

Hess D, Wu A, Golparian D, Esmaili S, Pandori W, Sena E, et al. Genome sequencing of a Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolate of a successful international clone with decreased susceptibility and resistance to extended-spectrum cephalosporins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:5633–41.

Ezewudo MN, Joseph SJ, Castillo-Ramirez S, Dean D, Del Rio C, Didelot X, et al. Population structure of Neisseria gonorrhoeae based on whole genome data and its relationship with antibiotic resistance. PeerJ. 2015;3:e806.

Ohnishi M, Unemo M. Phylogenomics for drug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:179–80.

Morita-Ishihara T, Unemo M, Furubayashi K, Kawahata T, Shimuta K, Nakayama S, et al. Treatment failure with 2 g of azithromycin (extended-release formulation) in gonorrhoea in Japan caused by the international multidrug-resistant ST1407 strain of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:2086–90.

Gose SO, Soge OO, Beebe JL, Nguyen D, Stoltey JE, Bauer HM. Failure of azithromycin 2.0 g in the treatment of gonococcal urethritis caused by high-level resistance in California. Sex Transm Dis. 2015;42:279–80.

Yasuda M, Ito S, Kido A, Hamano K, Uchijima Y, Uwatoko N, et al. A single 2 g oral dose of extended-release azithromycin for treatment of gonococcal urethritis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:3116–8.

Palmer HM, Young H, Winter A, Dave J. Emergence and spread of azithromycin-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Scotland. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:490–4.

Chisholm SA, Dave J, Ison CA. High-level azithromycin resistance occurs in Neisseria gonorrhoeae as a result of a single point mutation in the 23S rRNA genes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:3812–6.

Lynagh Y, Mac Aogáin M, Walsh A, Rogers TR, Unemo M, Crowley B. Detailed characterization of the first high-level azithromycin-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae cases in Ireland. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015 Apr 22. [Epub ahead of print].

Starnino S, Stefanelli P. Neisseria gonorrhoeae Italian Study Group I. Azithromycin-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains recently isolated in Italy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63:1200–4.

Unemo M, Golparian D, Hellmark B. First three Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates with high-level resistance to azithromycin in Sweden: a threat to currently available dual-antimicrobial regimens for treatment of gonorrhea? Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;58:624–5.

Katz AR, Komeya AY, Soge OO, MKiaha MI, Lee MV, Wasserman GM, et al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae with high-level resistance to azithromycin: case report of the first isolate identified in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:841–3.

Galarza PG, Abad R, Canigia LF, Buscemi L, Pagano I, Oviedo C, et al. New mutation in 23S rRNA gene associated with high level of azithromycin resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:1652–3.

Stevens K, Zaia A, Tawil S, Bates J, Hicks V, Whiley D, et al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates with high-level resistance to azithromycin in Australia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:1267–8.

Bala M, Kakran M, Singh V, Sood S, Ramesh V; Members of WHO GASP SEAR Network. Monitoring antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in selected countries of the WHO South-East Asia Region between 2009 and 2012: a retrospective analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89 Suppl 4:iv28-35.

Dillon JA, Trecker MA, Thakur SD; Gonococcal Antimicrobial Surveillance Program Network in Latin America and the Caribbean 1990–2011. Two decades of the gonococcal antimicrobial surveillance program in South America and the Caribbean: challenges and opportunities. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89 Suppl 4:iv36-iv41.

Kirkcaldy RD, Kidd S, Weinstock HS, Papp JR, Bolan GA. Trends in antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the USA: the Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP), January 2006-June 2012. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89 Suppl 4:iv5-10.

Lahra MM, Lo YR, Whiley DM. Gonococcal antimicrobial resistance in the Western Pacific Region. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89 Suppl 4:iv19-23.

Spiteri G, Cole M, Unemo M, Hoffmann S, Ison C, van de Laar M. The European Gonococcal Antimicrobial Surveillance Programme (Euro-GASP)--a sentinel approach in the European Union (EU)/European Economic Area (EEA). Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89 Suppl 4:iv16-iv18.

Lee H, Hong SG, Soe Y, Yong D, Jeong SH, Lee K, et al. Trends in antimicrobial resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolated from Korean patients from 2000 to 2006. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38:1082–6.

Boslego JW, Tramont EC, Takafuji ET, Diniega BM, Mitchell BS, Small JW, et al. Effect of spectinomycin use on the prevalence of spectinomycin-resistant and penicillinase-producing Neisseria gonorrhoeae. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:272–8.

Easmon CS, Forster GE, Walker GD, Ison CA, Harris JR, Munday PE. Spectinomycin as initial treatment for gonorrhoea. Br Med J. 1984;289:1032–4.

Ison CA, Littleton K, Shannon KP, Easmon CS, Phillips I. Spectinomycin resistant gonococci. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983;287:1827–9.

Unemo M, Golparian D, Limnios A, Whiley D, Ohnishi M, Lahra MM, et al. In vitro activity of ertapenem vs. ceftriaxone against Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates with highly diverse ceftriaxone MIC values and effects of ceftriaxone resistance determinants - ertapenem for treatment of gonorrhea? Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:3603–9.

Quaye N, Cole MJ, Ison CA. Evaluation of the activity of ertapenem against gonococcal isolates exhibiting a range of susceptibilities to cefixime. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:1568–71.

Hauser C, Hirzberger L, Unemo M, Furrer H, Endimiani A. In vitro activity of fosfomycin alone and in combination with ceftriaxone or azithromycin against clinical Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:1605–11.

Brown LB, Krysiak R, Kamanga G, Mapanje C, Kanyamula H, Banda B, et al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae antimicrobial susceptibility in Lilongwe, Malawi, 2007. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37:169–72.

Chisholm SA, Quaye N, Cole MJ, Fredlund H, Hoffmann S, Jensen JS, et al. An evaluation of gentamicin susceptibility of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates in Europe. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:592–5.

Dowell D, Kirkcaldy RD. Effectiveness of gentamicin for gonorrhoea treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89:142–7.

Hathorn E, Dhasmana D, Duley L, Ross JD. The effectiveness of gentamicin in the treatment of Neisseria gonorrhoeae: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2014;3:104.

Biedenbach DJ, Turner LL, Jones RN, Farell DJ. Activity of JNJ-Q2, a novel fluoroquinolone, tested against Neisseria gonorrhoeae, including ciprofloxacin-resistant strains. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;74:204–6.

Robert MC, Remy JM, Longcor JD, Marra A, Sun E, Duffy EM. In vitro activity of delafloxacin against Neisseria gonorrhoeae clinical isolates. STI & AIDS World Congress 2013. 14–17 July, 2013, Vienna, Austria.

Hamasuna R, Yasuda M, Ishikawa K, Uehara S, Hayami H, Takahashi S, et al. The second nationwide surveillance of the antimicrobial susceptibility of Neisseria gonorrhoeae from male urethritis in Japan, 2012–2013. J Infect Chemother. 2015;21:340–5.

Kazamori D, Aoi H, Sugimoto K, Ueshima T, Amano H, Itoh K, et al. In vitro activity of WQ-3810, a novel fluoroquinolone, against multidrug-resistant and fluoroquinolone-resistant pathogens. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2014;44:443–9.

Kerstein K, Fyfe C, Sutcliffe JA, Grossman TH. Eravacycline (TP-434) is active against susceptible and multidrug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae. 53rd Annual ICAAC. 10–13 September, 2013, Denver, CO, USA. Poster E-1181.

Zhang YY, Zhou L, Zhu DM, Wu PC, Hu FP, Wu WH, et al. In vitro activities of tigecycline against clinical isolates from Shanghai. China Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;50:267–81.

Alexander BT, Marschall J, Tibbetts RJ, Neuner EA, Dunne Jr WM, Ritchie DJ. Treatment and clinical outcomes of urinary tract infections caused by KPC-producing Enterobacteriaceae in a retrospective cohort. Clin Ther. 2012;34:1314–23.

Falagas ME, Karageorgopoulos DE, Dimopoulos G. Clinical significance of the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics of tigecycline. Curr Drug Metab. 2009;10:13–21.

Nix DE, Matthias KR. Should tigecycline be considered for urinary tract infections? A pharmacokinetic re-evaluation. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:1311–2.

Fujimoto K, Takemoto K, Hatano K, Nakai T, Terashita S, Matsumoto M, et al. Novel carbapenem antibiotics for parenteral and oral applications: in vitro and in vivo activities of 2-aryl carbapenems and their pharmacokinetics in laboratory animals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:697–707.

Koeth LM, Fisher J. In vitro activity of dalbavancin against Neisseria gonorrhoeae and development of a broth microdilution method. IDWeek 2013. 2–6 October, 2013, San Francisco, Calif, USA. Poster 255.

Jacobsson S, Golparian D, Phan LT, Ohnishi M, Fredlund H, Or YS, et al. In vitro activities of the novel bicyclolides modithromycin (EDP-420, EP-013420, S-013420) and EDP-322 against MDR clinical Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates and international reference strains. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:173–7.

Golparian D, Fernandes P, Ohnishi M, Jensen JS, Unemo M. In vitro activity of the new fluoroketolide solithromycin (CEM-101) against a large collection of clinical Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates and international reference strains including those with various high-level antimicrobial resistance-potential treatment option for gonorrhea? Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:2739–42.

Llano-Sotelo B, Dunkle J, Klepacki D, Zhang W, Fernandes P, Cate JH, et al. Binding and action of CEM-101, a new fluoroketolide antibiotic that inhibits protein synthesis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:4961–70.

Still JG, Schranz J, Degenhardt TP, Scott D, Fernandes P, Gutierrez MJ, et al. Pharmacokinetics of solithromycin (CEM-101) after single or multiple oral doses and effects of food on single-dose bioavailability in healthy adult subjects. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:1997–2003.

Hook E III, Oldach D, Jamieson B, Clark K, Fernandes P. 2013. A phase 2 study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of single dose solithromycin (CEM-101) for the treatment of patients with uncomplicated urogenital gonorrhoea. 23rd European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 27–30 April, 2013, Berlin, Germany. Abstract O274.

Paukner S, Gruss A, Fritsche TR, Ivezic-Schoenfeld Z, Jones RN. In vitro activity of the novel pleuromutilin BC-3781 tested against bacterial pathogens causing sexually transmitted diseases (STD). 53rd Annual ICAAC. 10–13 September, 2013, Denver, CO, USA. Poster E-1183.

Bouchillon SK, Hoban DJ, Hackel MA, Butler DL, Memarsh P, Alley MRK. In vitro activities of AN3365: a novel boron containing protein synthesis inhibitor, and other antimicrobial agents against anaerobes and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. 50th Annual ICAAC. 12–15 September, 2010, Boston, MA, USA. Poster F1-1640.

Swanson S, Lee CJ, Liang X, Toone E, Zhou P, Nicholas R. LpxC inhibitors as novel therapeutics for treatment of antibiotic-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae. 18th International Pathogenic Neisseria Conference. 9–14 September, 2012, Wurzburg, Germany.

Escaich S, Prouvensier L, Saccomani M, Durant L, Oxoby M, Gerusz V, et al. The MUT056399 inhibitor of FabI is a new antistaphylococcal compound. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:4692–7.

Jeverica S, Golparian D, Hanzelka B, Fowlie AJ, Matičič M, Unemo M. High in vitro activity of a novel dual bacterial topoisomerase inhibitor of the ATPase activities of GyrB and ParE (VT12-008911) against Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates with various high-level antimicrobial resistance and multidrug resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:1866–72.

Jacobsson S, Golparian D, Alm RA, Huband M, Mueller J, Jensen JS, et al. High in vitro activity of the novel spiropyrimidinetrione AZD0914, a DNA gyrase inhibitor, against multidrug resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates suggests a new effective option for oral treatment of gonorrhea. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:5585–8.

Huband MD, Bradford PA, Otterson LG, Basarab GS, Kutschke A, Giacobbe R, et al. In vitro antibacterial activity of AZD0914: a new spiropyrimidinetrione DNA Gyrase/Topoisomerase inhibitor with potent activity against Gram-positive, fastidious Gram-negative, and atypical bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:467–74.

Unemo M, Ringlander J, Wiggins C, Fredlund H, Jacobsson S, Cole M, the European Collaborative Group. High in vitro susceptibility to the novel spiropyrimidinetrione ETX0914 (also known as AZD0914) among 873 contemporary clinical Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates in 21 European countries during 2012–2014. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015 june 15. [Epub ahead of print]

Palmer T, Walkup G, Basarab G, Fan J, Mills SD, Shapiro A, et al. 2014. AZD0914: A Neisseria gonorrhoeae Topoisomerase II inhibitor with novel mode of inhibition, poster C-1422. Abstr. 54th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC, USA.

Alm RA, Lahiri SD, Kutschke A, Otterson LG, McLaughlin RE, Whiteaker JD, et al. Characterization of the novel DNA gyrase inhibitor AZD0914: Low resistance potential and lack of cross-resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:1478–86.

Basarab GS, McNulty J, Gales S, Powles-Glover N, Prior H, Lengel D, et al. 2014. Non-clinical safety profile of a novel gyrase inhibitor for treatment of Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections, poster F-268. Abstr. 54th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC, USA.

Lawrence K, O’Connor K, Atuah K, Matthews D, Gardner H. 2014. Safety and pharmacokinetics of single escalating oral doses of AZD0914: a novel spiropyrimidinetrione antibacterial agent, poster F-267. Abstr. 54th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC, USA.

Jerse AE, Deal CD. Vaccine research for gonococcal infections: where are we? Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89 Suppl 4:iv63–8.

Acknowledgements

Work in the WHO Collaborating Centre for Gonorrhoea and other STIs is supported by Örebro Univeristy Hospital, Department of Laboratory Medicine, the Research Committee of Örebro County and the Örebro University Hospital Foundation, Örebro, Sweden.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author has been investigator in in vitro studies for new antimicrobials (solithromycin, VXc-486, modithromycin, EDP-322 and ETX0914), and the pharmaceutical companies supported with 0-49 % of the laboratory cost in these studies.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Unemo, M. Current and future antimicrobial treatment of gonorrhoea – the rapidly evolving Neisseria gonorrhoeae continues to challenge. BMC Infect Dis 15, 364 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-015-1029-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-015-1029-2