Abstract

Background

Seasonal influenza vaccine was once part of the routine immunization schedule that is routinely offered to all children in Japan, but it is now excluded from the schedule. This study aimed to investigate factors influential to parents’ decision to have their children receive seasonal influenza vaccine, as well as types of seasonal influenza vaccine information that is given to parents.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional online survey of 555 participants who have at least one child younger than 13 years of age. Respondents were asked to categorize the history of influenza vaccination of their youngest child as either ‘annual’ , ‘sometimes’ , or ‘never’. Participants were also asked about potentially influential factors in their decision to have their children receive a seasonal influenza vaccine.

Results

A total of 75% of respondents answered that their youngest child had received a seasonal influenza vaccine, and 57% of respondents answered that their child receives the vaccine every year. The higher income group was more likely than the lowest income group to have a history of influenza vaccine uptake. A recommendation from a pediatrician or school/nursery to have their child vaccinated was also positively associated with a history of influenza vaccine uptake. The most common reason for a pediatrician’s recommendation was ‘it leads to milder symptoms if infected’.

Conclusions

The main finding of the study is a significant association between household income and influenza vaccination of the youngest child in the household. We also found that cost could be a barrier to vaccinating children in low income households and that information from pediatricians and schools/nurseries could motivate parents to have their children vaccinated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In Japan, routine vaccination is defined by the Preventive Vaccinations Act, while voluntary vaccination is not regulated by the law. Although voluntary vaccines are approved by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare under the Pharmaceutical Affairs Law, they are not vaccines that are required by Preventive Vaccinations Act [1,2]. In recent years, some vaccines such as Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) vaccine and pediatric pneumococcal conjugate vaccine have been added in the routine immunization schedule [3]. Seasonal influenza vaccination is designated as a routine vaccination for the elderly but voluntary vaccination for children [2]. Historically, seasonal influenza vaccination was part of the routine immunization schedule offered to schoolchildren, and the vaccine was administered by mass vaccination of schoolchildren in classrooms. However, in 1994 it was excluded from the routine immunization schedule as a result of a negative campaign against influenza vaccination that began in the late 1980s that questions vaccine efficacy and emphasizes vaccine risks and adverse events. As a result of this change, the decision to vaccinate children against seasonal influenza has been left to the discretion of parents, who must pay for the vaccine out-of-pocket [1,4]. In the 2010/11 influenza season the coverage rate of seasonal influenza vaccine among children was estimated to be 11% in children younger than 1 year old, 70% in those 1–6 years old, and 58% in those 6–13 years old [5].

Many studies have shown the usefulness of influenza vaccination for the prevention of influenza infection and disease. Some studies report that immunizing children can protect not only the children but also the community from seasonal influenza [6]. Mass vaccination of schoolchildren in Japan is being revalued for its protective impact on influenza-associated mortality among young children and older persons, as well as reducing class cancellation in schools [7-9]. Many advisory groups, including the Japan Pediatric Society, recommend that healthy children aged 6 months and older receive the influenza vaccine [10-12]. This study aims to investigate factors influential to parents’ decision to have their children receive the seasonal influenza vaccine in Japan.

Methods

Respondents were recruited from a registered online survey panel of a web-based private survey company in January 2013. Parents who had at least one child under 13 years of age were asked to participate in the full survey (approximately n = 6,000). Recruitment ceased when the number of respondents reached the target of 555. This number was estimated from the main hypothesis that the influenza coverage rate is 65% for the higher income group, and 55% for the lower income group from data indicating that influenza vaccination coverage among children is around 60%. The significance level α was set at 0.05, and the power at 0.55. Therefore it was necessary to study about 250 respondents from each income group [13]. We then employed a survey company that ultimately collected 555 responses. Because this survey is of a non-random sample, the geographic structure of the child population distribution of the participants was adjusted to be similar to nationwide statistics in Japan. Household income of respondents was also adjusted to fit the distribution of household incomes of families with children based on nationwide statistics [14,15].

For factors that are potentially influential to childhood vaccine uptake, we inquired about respondents’ education, marital status, number of children, household income, mother’s employment, youngest child’s history of influenza and history of influenza vaccine receipt, and recommendation(s) from a pediatrician or school/nursery. The three categories of history of influenza vaccine were ‘annual’ , ‘sometimes’ , and ‘never’. The four categories of recommendation on influenza vaccination from a pediatrician were shown as ‘yes’ , ‘either vaccination or not is acceptable’ , ‘recommended no vaccination’ , or ‘did not make a recommendation’ , and respondents were asked to choose one of the four. ‘Either vaccination or not is acceptable’ means that either option was equally acceptable, and the pediatrician left the decision to the parents. ‘Recommended no vaccination’ means that the pediatrician said the child should not receive the vaccine. We also inquired about the types of information offered by pediatricians when recommending influenza vaccination. For the recommendation from a school/nursery, the four categories were ‘yes’ , ‘either vaccination or not is acceptable’ , ‘child does not go to any school/nursery’ , and ‘did not make a recommendation’.

Ordered logit models were applied to investigate associations between the history of influenza vaccination and possible factors influencing vaccination. The dependent variable, the history of influenza vaccination of the youngest child, was coded as 2 if parents reported ‘annual’ , as 1 if ‘sometimes’ , and as 0 if ‘never’. Each variable was first examined by bivariate analysis. Variables that could possibly influence vaccination included: the number of children; household income (unit: 10,000 yen [US$112]); mother’s employment (full time job, part time job, self-employed, or unemployed); years of education of the respondent; marital status of the respondent (married or other); prior diagnoses of influenza in the youngest child (yes [including maybe] or no/do not remember); and recommendation from the pediatrician (yes, either vaccination or not is acceptable, recommended no vaccination, or did not make a recommendation) and the school/nursery (yes, either vaccination or not is acceptable, did not make a recommendation or the child does not attend any school). Although we considered the age of the child as a possible confounder, we did not find any strong associations with other variables. Multivariate analysis was then conducted to adjust for the effects of other variables. We considered differences significant at p < 0.05. The survey protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of Meiji Pharmaceutical University. Informed consent was obtained from all respondents.

Results

Respondents’ characteristics are shown in Table 1. More than half of the respondents were female (59%), 57% were aged 30–39 years, and the vast majority (97%) were married. The mean number of years of education of the respondent was 15 years, and the most common educational background was a bachelor’s degree (42%). The average annual household income was 6.7 million yen (US$75,506).

A total of 75% of respondents answered that their youngest child had received a seasonal influenza vaccine, and 57% of respondents answered that their youngest child receives the vaccine every year (Table 2). During the 2012/13 season, 58% of children aged < 6 years old, and 64% of those aged 6–13 years old in this study received a seasonal influenza vaccine. Less than half of the respondents (43%) reported that their youngest child had a prior diagnosis of influenza. A majority of respondents (60%) answered that the child’s mother was unemployed. A total of 14% of respondents received a recommendation from a pediatrician, and 13% of respondents received a recommendation from a school/nursery (Table 2).

In bivariate analysis, years of schooling of the respondent, and previous influenza diagnosis in the child were positively associated with a history of influenza vaccination for the youngest child (Table 3). A recommendation from a pediatrician or a school/nursery was positively associated with a history of influenza vaccination for the youngest child, compared with ‘did not make a recommendation’. The higher income group was more positively associated with a history of influenza vaccine uptake than the lowest income group. Conversely, compared with ‘did not make a recommendation’ , ‘recommended no vaccination’ by a pediatrician and having a child not go to a school/nursery showed significant negative correlations with a history of influenza vaccination for the youngest child.

In the multivariate model, the higher income group was more likely than the lowest income group to have a history of influenza vaccine uptake (Table 3). Like the bivariate analysis, a recommendation from a pediatrician or school/nursery was significantly associated with a history of influenza vaccination of the youngest child, compared with ‘did not make a recommendation’. Additionally, ‘recommended no vaccination’ by a pediatrician and having a child not go to a school/nursery showed significant negative correlations with the history of influenza vaccination for the youngest child, compared with ‘did not make a recommendation’. However, compared with ‘did not make a recommendation’, a pediatrician’s advice of ‘either vaccination or not is acceptable’ was not significantly associated with a history of influenza vaccination of the youngest child.

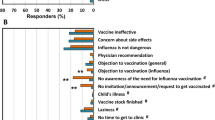

Of the reasons for a pediatrician to recommend influenza vaccination, the most common was ‘symptoms are mild if infected’ (47%) followed by ‘to prevent influenza infections’ (24%) (Table 4). Reasons for pediatricians to not recommend an influenza vaccination were because of an individual child’s characteristics such as an egg allergy; however, recommendations against vaccination were few.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore factors influencing parents’ decisions to have their children receive the seasonal influenza vaccine in Japan. The main finding of the study is a significant association between household income and influenza vaccination of the youngest child in the household. Socioeconomic determinants have been explored as factors to explain influenza vaccine uptake in many countries [16]. In the Japanese setting, because seasonal influenza vaccination for children is voluntary, parents must pay for the vaccine out-of-pocket. The recommendation in Japan is for children to receive influenza vaccine twice during each winter season [11]. According to a survey by a private company in 2008, the average price per child is 2,702 yen (US$30) for the first shot and 2,379 yen (US$27) for the second [17]. Therefore, the associated cost for influenza vaccination could be a heavy burden on low income households. Prior research showed that preventive medicine, including influenza vaccination, is favored by higher socioeconomic groups [18,19]. Although we cannot definitively state that our results showed inequity, we can say that cost could be a barrier to vaccinating children in low income households. Therefore, financial support for influenza vaccination for low income households might improve children’s influenza vaccination coverage [20]. Moreover, if unvaccinated children were infected with influenza, they may have more severe disease and be more likely to visit a physician than vaccinated children [21]. The burden of disease could be heavy on households as well as children.

Other findings of this study were that parents given a recommendation from a pediatrician and/or school/nursery were more likely to have their youngest child vaccinated. Information from pediatricians and schools/nurseries as trusted information sources could motivate parents to have their children vaccinated [22]. However, in this study parents reported that pediatricians did not always emphasize vaccine efficacy to protect against influenza. These results might reflect what Hirota & Kaji [4] stated: ‘many physicians and pediatricians usually make apologies when administering influenza vaccine, explaining that “Every vaccine recipient cannot necessarily avoid contracting influenza”.

We recognize some limitations to this study. One limitation is the fact that the number of respondents is a relatively small number (555). Additionally, this was a web-based survey; thus, respondents were limited to the population who can access the Internet. This could cause selection bias. However, in Japan over 90% of the population aged 20–50 years could access the Internet in 2011 [23]. To reduce the possibility of selection bias, the distribution of the participants was adjusted to be similar to nationwide statistics in Japan. Another limitation is the potential of recall bias, because parents who answered that their youngest child had received a seasonal influenza vaccine could remember a recommendation by a pediatrician or school/nursery more than parents who did not have their youngest child vaccinated. This research did not examine the information from the schools/nurseries in detail, nor assess information from web sites or social networks (family, friends). These information sources may influence parents’ knowledge and decision-making [24]. This study also did not assess parents’ attitude and beliefs [25]. Finally, we did not consider any vaccination-related costs, including respondents’ travel costs. Further studies should be conducted to consider this aspect.

Conclusions

The main finding of the study is a significant association between household income and influenza vaccination of the youngest child in the household. Financial support for low income households might improve influenza vaccination coverage in children, because the cost could be a barrier to vaccinating children in low income households. Additionally, information from pediatricians and schools/nurseries could motivate parents to have their children vaccinated.

References

Saitoh A, Okabe N. Current issues with the immunization program in Japan: can we fill the “vaccine gap”? Vaccine. 2012;30:4752–6.

The Review Committee for Vaccination Guidelines. Vaccination and Children’s Health. Tokyo: Public Foundation of the Vaccination Research Center; 2013.

Saitoh A, Okabe N. Recent progress and concerns regarding the Japanese immunization program: Addressing the “vaccine gap”. Vaccine. 2014;32:4253–8.

Hirota Y, Kaji M. History of influenza vaccination programs in Japan. Vaccine. 2008;26:6451–4.

Nobuhara H, Watanabe Y, Miura Y. A study on prediction of demand for influenza vaccine during the 2011/12 season in Japan. Jpn J Human Sci Health-Soc Serv. 2013;19:31–6 [in Japanese].

Loeb M, Russell ML, Moss L, Fonseca K, Fox J, Earn DJ, et al. Effect of influenza vaccination of children on infection rates in Hutterite communities: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;303:943–50.

Kawai S, Nanri S, Ban E, Inokuchi M, Tanaka T, Tokumura M, et al. Influenza vaccination of schoolchildren and influenza outbreaks in a school. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:130–6.

Reichert TA, Sugaya N, Fedson DS, Glezen WP, Simonsen L, Tashiro M. The Japanese experience with vaccinating schoolchildren against influenza. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:889–96.

Sugaya N, Takeuchi Y. Mass vaccination of schoolchildren against influenza and its impact on the influenza-associated mortality rate among children in Japan. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:939–47.

American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Infectious Diseases. Recommendations for prevention and control of influenza in children, 2013–2014. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e1089–104.

Japan Pediatric Society. Vaccination Schedule Recommended by the Japan Pediatric Society. 2014. Available: http://www.jpeds.or.jp/modules/en/index.php?content_id=7. Accessed April 22, 2014.

Usonis V, Anca I, Andre F, Chlibek R, Ivaskeviciene I, Mangarov A, et al. Central European Vaccination Advisory Group (CEVAG) guidance statement on recommendations for influenza vaccination in children. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:168.

Fleiss JL, Levin B, Paik MC. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions 3rd edition. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. Hoboken: Wiley-Interscience; 2003.

Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Jinkou Suikei (Heisei 23 nen juu gatsu 1nichi genzai). 2012. Available: http://www.stat.go.jp/data/jinsui/2011np/index.htm. Accessed October 29, 2013 [in Japanese].

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Heisei 22nen kokuminseikatsu kisochosa no gaikyo. 2011. Available: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/k-tyosa/k-tyosa10/. Accessed December 3, 2012 [in Japanese].

Endrich MM, Blank PR, Szucs TD. Influenza vaccination uptake and socioeconomic determinants in 11 European countries. Vaccine. 2009;27:4018–24.

QLife. Influenza yoboseshu zenkoku heikin kakaku o koukai. 2008. Available: http://www.qlife.jp/square/hospital/story875.html. Accessed October 28, 2013 [in Japanese].

Lorant V, Boland B, Humblet P, Deliège DJ. Equity in prevention and health care. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56:510–6.

Wada K, Smith DR. Influenza vaccination uptake among the working Age population of Japan: results from a national cross-sectional survey. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e59272.

Palache A. Seasonal influenza vaccine provision in 157 countries (2004–2009) and the potential influence of national public health policies. Vaccine. 2011;29:9459–66.

Ochiai H, Fujieda M, Ohfuji S, Fukushima W, Kondo K, Maeda A, et al. Inactivated influenza vaccine effectiveness against influenza-like illness among young children in Japan-with special reference to minimizing outcome misclassification. Vaccine. 2009;27:7031–5.

Bhat-Schelbert K, Lin CJ, Matambanadzo A, Hannibal K, Nowalk MP, Zimmerman RK. Barriers to and facilitators of child influenza vaccine: perspectives from parents, teens, marketing and healthcare professionals. Vaccine. 2012;30:2448–52.

Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Communications Usage Trend Survey in 2011. 2012. Available: http://www.soumu.go.jp/johotsusintokei/english/. Accessed October 10, 2013.

Almeida CM, Tiro JA, Rodriguez MA, Diamant AL. Evaluating associations between sources of information, knowledge of the human papillomavirus, and human papillomavirus vaccine uptake for adult women in California. Vaccine. 2012;30:3003–8.

Prislin R, Dyer JA, Blakely CH, Johnson CD. Immunization status and sociodemographic characteristics: the mediating role of beliefs, attitudes, and perceived control. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:1821–6.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AS participated in the concept and design of the study, participated in the analysis and interpretation of the data, and wrote the manuscript. MK participated in the concept and design of the study, the interpretation of the data. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Shono, A., Kondo, M. Factors associated with seasonal influenza vaccine uptake among children in Japan. BMC Infect Dis 15, 72 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-015-0821-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-015-0821-3