Abstract

Objectives

The relationship between handgrip strength (HGS) and quality of life is inconsistent. The purpose of this study was to investigate the potential association between HGS and quality of life in the settings of ageing and Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

Methods

We investigated the HGS, CASP-12 (control, autonomy, self-realization, and pleasure) measure of quality of life, and physical capacity in European adults above 50, including controls (n = 38,628) and AD subjects (n = 460) using the survey of health, ageing, and retirement in Europe (SHARE; 2022).

Results

AD subjects exhibited lower HGS and CASP-12 scores than controls (both p < 0.05). Participants with higher CASP-12 quartiles had higher HGS in controls but not in AD subjects. A linear positive relation was found between HGS and CASP-12 in controls (0.0842, p < 0.05) but not in AD subjects (0.0636, p = 0.091). There was no effect of gender on this finding. Lastly, we found significant negative associations of difficulties walking, rising from chair, climbing stairs, and fatigue with CASP-12 scores in controls and AD subjects (all p < 0.05).

Conclusions

Altogether, HGS was not associated with quality of life in individuals with AD. Conversely, difficulties in activities of daily living seem to be negatively associated with quality of life; thus, strategies are recommended to improve physical capacity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quality of life (QoL) is a complex concept associated with the mental, social, and physical well-being of older adults [1]. Several studies indicate a high efficacy of QoL in predicting morbidity and mortality in older adults [2, 3]. For example, individuals with elevated QoL have reduced risks of hospitalization, comorbidities, and death [3]. These people also demonstrate improved functional independence in activities of daily living [3].

Several instruments are available to evaluate the QoL [1]. Among them, control, autonomy, self-realization, and pleasure (CASP-12) may be of primary relevance [4]. CASP-12 was designed for individuals over 50 years old with an intent to distinguish basic human needs. In this context, it differs from other QoL instruments that primarily focus on physical functions [5]. Over the years, CASP-12 has emerged as an efficient, objective, and standardized assessment tool to evaluate QoL in the older population [4]. In addition, it demonstrates adequate psychometric properties that go beyond the physical health of the individual [6]. The mental correlates of CASP-12 have been cross-culturally validated in several countries [4, 6]. However, the associations of CASP-12 with physical correlates are poorly characterized and warrant further dissection for targeted interventions.

Age-related muscle decline, termed sarcopenia, is a critical determinant of reduced QoL in the older population [7]. Sarcopenia is a geriatric syndrome characterized by the loss of muscle mass and strength and reduced physical capacity [8]. Reduced handgrip strength (HGS) is widely accepted among the diagnostic parameters of sarcopenia [9]. Several studies indicate an association of reduced HGS with compromised mobility, functional decline, hospitalization, and social isolation [10,11,12]. In addition, HGS exhibits positive associations with several QoL assessment tools [10]. However, most such studies are regional, and its association with CASP-12 in the settings of a large continental dataset is relatively poorly characterized.

Among various age-related comorbidities, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is frequently associated with reduced QoL [6]. The subjects with AD also demonstrate reduced scores on CASP-12, indicating poor psychometric well-being [6]. The physical compromise in AD cohort is well established and also includes reduced HGS [13]. These findings indicate a potential association between CASP-12 and HGS in AD cohort. Specifically, it is possible that reduced psychometric well-being, as measured by CASP-12, may be associated with lower HGS. However, sarcopenia and muscle strength have multifactorial etiology, and the association of CASP-12 with HGS remains poorly characterized. Furthermore, such associations may be gender-specific, since gender differences exist in assessing QoL in older adults [14]. Lastly, most related studies investigate subsets of regional populations and may not represent large datasets. We aimed to investigate the associations between quality of life and HGS among more than 6000 European adults.

Materials and methods

The Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) is the dataset used for this study [15]. More specifically, wave 8 is used, which was conducted using face-to-face interviews from October 2019 until March 2020. SHARE is a representative harmonized panel-data survey covering 28 primarily European countries with the target population being people aged 50+. The SHARE collects data on different public health topics, socioeconomic factors, living conditions, as well as demographics, which enables drawing a complete picture of countries’ different vulnerable older adults.

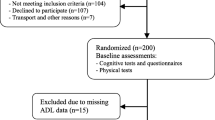

The questionnaire behind our applied data is documented in the SHARE database [15]. In the accessed data sets applied here (datasets with suffix sharew8_rel8-0-0_: cv_r, gv_weights, ph, gv_health, and gv_isced), 46,487 respondents were identified. After cleaning the data for missing observations or missing values, we ended up with 38,628 individuals, which was a 17% reduction in sample size. The main problems behind missing values were with the quality of life and HGS indicators. Many interviews of respondents with AD were conducted with the help of a proxy, who assisted the respondent or answered some or all the questions on behalf of the respondent. Thus, it is possible that the respondents with AD in our dataset represent the healthier ones compared to the AD subjects in the whole data set. And we do see that among AD subjects in the reduced sample, much fewer suffer from walking and climbing difficulties compared to the whole sample. When estimating different parameters, data were weighted by applying household weights (variable cciw_w8_main), e.g., we used population weights giving us estimates for the adults above 50. It should be noted that SHARE data is de-identified (in terms of European law it is “pseudonymized”), such that respondents cannot be identified. In our study, we only report aggregated information, ensuring the anonymity of individual respondents.

HGS was assessed by the questionnaire’s grip strength (GS) module. The communication in this regard was: “Now I would like to assess the strength of your hand in a gripping exercise. I will ask you to squeeze this handle as hard as you can, just for a couple of seconds and then let go. I will demonstrate it now”; “I will take two alternate measurements from your right and your left hand. Would you be willing to have your handgrip strength measured?”; “Which is your dominant hand?”. The maximum value of all – up to four -measurements was used as an indicator of HGS if at least two valid measures for one hand were available and the two measures for the same hand did not differ more than 20 kg.

The subjective well-being of the respondents was based on 12 well-being indicators (three questions for each of the sub-scales control, autonomy, self-realization, and pleasure) introduced by phrasing, ‘’I will now read a list of statements that people have used to describe their lives or how they feel. We would like to know how often, if at all, you experienced the following feelings and thoughts: often, sometimes, rarely, or never”. The answers were given scores of 1 (often), 2, 3, and respectively 4 (never). The first indicator was “How often do you think your age prevents you from doing the things you would like to do?” and the last indicator was phrased as “How often do you feel that the future looks good for you?”. Thus, higher scores were associated with higher well-being. The composite index summarized in CASP-12 is the sum of the scores for each of the 12 indicators and thus varied frpm 4 (least possible well-being) to 48 (highest possible well-being).

In the questionnaire, after showing the respondent a list of 21 diseases/2 other options, AD was identified through the question “Has a doctor ever told you that you had/ Do you currently have any of the conditions on this card? [With this, we mean that a doctor has told you that you have this condition and that you are either currently being treated for or bothered by this condition”. The same method was used to identify hypertension, high cholesterol levels, diabetes, chronic lung disease, cancer, and chronic kidney disease.

One can expect differences between different socio-economic groups’ HGS-CASP-12-AD nexus. Therefore, statistical tests were carried out to investigate inter-group differences regarding well-being and hand grip strength. The standard t-test was used. For multivariate analysis a linear OLS regression was used to estimate the effects of AD and HGS on CASP-12.

Results

The primary characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1. The sample consists of 16,935 males and 21,693 females. Apart from HGS, the distribution across different measures was mostly similar for males and females. A major part of the studied population was in their 60 or 70 s, while fewer were in their 50s or above 80. Around one-fourth had a tertiary education, while 1.2% of the population had AD. More than 40% had well-being levels between 40 and 48. 2.4% of males had HGS up to 20, while the corresponding percentage for females was 21.9%. Less than 2% of respondents had BMI of at least 40 and were labeled as severely overweight. Nearly half of the selected population suffered from hypertension, one-fourth had high plasma cholesterol levels, and 13–16% were diagnosed with diabetes mellitus. 8–10% of the study population had difficulty walking, 15–20% had difficulty getting up from a chair, and 9–13% had difficulty climbing one flight of stairs. 17–23% had fatigue problems. 6% suffered from lung disease, 5–7% had cancer, 14–24% had osteoarthritis, and 2% had kidney disease.

We next investigated the interplay of HGS and well-being with AD (Fig. 1). As expected, we observed that higher HGS was associated with higher scores on CASP-12 in males (Fig. 1A) and females (Fig. 1B). This relationship was more robust for non-Alzheimer’s respondents compared to AD subjects (the blue 95% confidence intervals were much narrower than the red CIs). Interestingly, the curves are steeper for females than males, meaning that a 1-point increase in HGS lead to a higher increase in CASP-12 for females than males.

Females had lower HGS than males, so we used different standardized thresholds for normal HGS for both genders, e.g., 27 kg for males and 16 kg for females. We observed that the well-being was mostly the same for males and females after applying HGS thresholds (Table 2). We also found systematic difference in CASP-12 scores between respondents above and below the thresholds, e.g., controls with normal HGS had CASP-12 around 38, while it was around 34 for respondents below normal HGS. But the difference was marginal among AD respondents. The difference between controls and AD was nearly 6 kg for normal HGS, which was highly significant (p < 0.001). There was also a difference between controls and AD for below-normal HGS, but it was 2 kg and failed to achieve statistical significance.

Additionally, among control subjects, HGS was higher with higher CASP-12 quartile in males and females (Table 3). In the lowest CASP-12 quartile, HGS was 39.1 kg for males and 24 kg for females. Conversely, in the highest CASP-12 quartile, the HGS was 45.2 kg for males and 27.7 kg for females. However, a similar systematic relation between HGS and CASP-12 was not observed in AD respondents. For every CASP-12 quartile for both genders, we observed that the HGS was higher for controls than AD subjects, and the differences between the controls and AD subjects (5.3 to 11.4 kg) was highly significant (except for females in the CASP-12 third quartile, where the difference of 1.4 kg was not statistically significant).

In the above descriptive analysis, we did not control for comorbidities or demographics, such as age, educational level, and the country of residence. All of this is considered in the CASP-12 regressions presented in Table 4. In the overall regression, we observed that higher HGS was associated with higher CASP-12 scores. For example, a 1-point increase in HGS was associated with a 0.0821 point higher CASP-12. The presence of AD was associated with lower CASP-12 by 1.569. Additionally, AD reduced the relation between HGS and CASP-12 by 0.0452. For example, the sensitivity of CASP-12 to HGS was roughly halved from 0.0821 to 0.0369, albeit it was not statistically significant. After applying regression between controls and AD subjects separately, we observed that the relationship between HGS and CASP-12 was nearly unchanged for controls (1-point increase in HGS lead to a 0.0809 increase in CASP-12) and AD subjects (1-point increase in HGS lead to 0.0793 increase in CASP-12). In separate regressions for males and females, we found robust relationship between HGS and CASP-12 for controls (0.0773 for males and 0.1010 for females) and a relatively modest and statistically insignificant relation for AD (0.0735 for males and 0.0722 for females). Together, these observations show a lack of association between HGS and well-being for AD subjects.

Discussion

We report that the reduced HGS and CASP-12 were common findings in subjects with AD. These subjects also exhibited difficulties performing several household motor tasks compared to controls. We found significant correlations between difficulties in performing household tasks and CASP-12 scores in AD subjects. However, to our surprise, we did not find a similar robust correlation of HGS with CASP-12 in AD subjects. This finding was consistent across both genders and indicates that HGS may not be primarily associated with CASP-12 in AD.

The reduced HGS and difficulties in performing daily motor tasks in AD subjects is consistent with previous reports [13, 16]. This is partly due to accelerated neurodegeneration, which affects skeletal muscle and motor systems. In addition, these subjects also have reduced physical activity, which may further exacerbate neural and/or motor decline. Accordingly, several reports indicate an association between sarcopenia and CASP-12 scores in older adults [7, 17]. Thus, we expected a robust negative association between HGS and CASP-12 scores in AD subjects. However, our finding of a weak association between HGS and CASP-12 in AD subjects is counterintuitive. It must be noted that HGS is a measure of upper body strength and may have a relatively lesser role in ensuring functional independence and quality of life than lower body strength. For example, several activities of daily living, such as walking, rising from the chair, and climbing stairs, primarily depend on lower limb strength with minimal contribution from handgrip muscles [18]. It is generally recognized that the activities requiring lower extremities strength are lost earlier than the upper limb strength in individuals with AD [19, 20]. Thus, the discriminatory role of HGS in mobility and lower body strength may not be well established and is reduced in subjects with optimal muscle strength [21]. A functionally independent lifestyle is a critical driver of higher CASP-12 scores in older population [4]. For example, subjects with difficulty in performing activities of daily living exhibit reduced CASP-12 scores [7]. Thus, we next investigated the associations of CASP-12 with difficulties in performing activities of daily living. We found consistent and robust negative associations of CASP-12 with difficulties in walking, getting up from chair, and climbing stairs and a higher fatigue sensitivity. These novel findings in AD subjects are generally consistent with the efficacy of CASP-12 in predicting physical dependency in older adults [7].

Previous studies also indicate the associations of CASP-12 with sarcopenia in older population [7, 17]. We did not evaluate sarcopenia in the study population. However, we measured HGS, which exhibited a weak association with CASP-12 in AD subjects. It must be noted that sarcopenia is a composite syndrome with multiple causative factors and phenotypes [22,23,24]. A low grip strength is an individual component of sarcopenia [25]. In addition, the HGS measurements do not consider muscle power, which may be a stronger predictor of physical capacity. Findings from the older population indicate a disproportionate loss of muscle strength between upper and lower extremities [18]. On the other hand, the loss of muscle power is generally consistent between upper and lower limbs [18]. Lastly, it must be noted that CASP-12 intends to distinguish basic human needs, unlike other QoL tools, which rely on physical health. Thus, the reduced CASP-12 scores in AD subjects may primarily be independent of reduced HGS. Together, these findings may translate into the absence of a robust association between HGS and CASP-12 in AD subjects.

Contrary to AD subjects, the control population exhibited robust associations of CASP-12 with HGS. However, the control population also exhibited higher HGS than AD subjects. It is possible that at higher HGS, the CASP-12 is at least partly governed by HGS. This notion is consistent with the positive association of HGS with mental health in older adults [26]. Additionally, HGS also demonstrates a positive association with physical health in advanced age [26]. However, these effects may partly be dependent on the amount of HGS. For example, at lower HGS, the lower limb strength and difficulties in performing daily motor tasks become the prime determinants of CASP-12 [21]. Most previous studies dissecting the association between HGS, and quality of life overlook the lower limb functioning. In general, older adults with lower limb dysfunction also exhibit lower HGS. However, some level of discord between the functions of lower and upper limb is reported [18]. It is possible that this discord can at least partly explain the reduced predictive potential of HGS in describing CASP-12 in AD subjects.

We found relatively lower CASP-12 scores among women than men irrespective of disease status, which is consistent with recent data from Europe [27]. Women with low HGS are more likely to have reduced psychosocial health than men [28]. In addition, women exhibit a more rapid decline of lower extremities strength and mobility than men [21]. Together, these findings may account for lower CASP-12 scores in women than men.

The data presented in this study represent a 17% reduction from the original dataset of 46,487 subjects. This was primarily due to missing data about HGS and CASP-12. This reduction did not significantly change the age and gender distribution of subjects but reduced the prevalence of AD from 2.02 to 0.82%. AD subjects exhibit reduced mental and physical well-being compared to age-matched controls [6, 13, 16]. For example, they demonstrate depression, reduced cognition, and muscle weakness for the given age. Thus, it is possible that the physical and mental decline in AD subjects may have prevented obtaining reliable data regarding HGS and CASP-12.

Pain is a critical determinant of QoL. Older adults may suffer from neuropathic pain due to comorbidities and somatosensory disturbances [29]. It is generally recognized that pain affects several QoL domains, including physical and emotional health [30]. It is possible that the potential presence of pain sensation may have affected the QoL data reported in this study. However, various domains of CASP-12 do not evaluate pain sensation. Therefore, we did not investigate pain sensation as a potential confounding factor in this study.

The major strengths of this study are a large sample size of participants with representative proportions population from various geographical regions of Europe. The diversity of the study population increases the global relevance of our findings. The HGS dynamometer is an objective tool and can be used in most clinical and domestic settings without technical expertise. We applied the CASP-12 as an internationally recognized measure of psychometric health standardized across the study population. However, this study has certain limitations. Any causal inference between physical and mental health should be cautiously interpreted due to the cross-sectional design of this study. We cannot validate the temporal stability of our findings due to lack of longitudinal data. We overlooked the comorbidities of participants in the control group. The data from some AD subjects was collected with the help of a proxy, which can potentially bias our results. However, SHARE is an internally recognized platform, and we are confident that all data was collected and validated in a standardized manner. Therefore, we are confident about the quality of our data. Lastly, it is possible that a significant number of AD subjects were not included in this study due to lack of data regarding HGS and CASP-12. Thus, the final sample size in this study may represent a selected pool of AD subjects from European countries.

Altogether, we report a reduction in HGS and CASP-12 in European adults with AD. However, HGS was not primarily associated with reduced CASP-12 in AD subjects. Conversely, the difficulties in performing daily motor tasks emerged as superior tools for dictating mental health in these subjects. Future studies should further characterize the physical and mental health in AD with mechanistic perspectives.

Data Availability

SHARE Data is available free of charge for scientific purpose. Data access can be applied by the SHARE Research Data Center, see SHARE website: https://share-eric.eu/data/data-access. Access to the data collected and generated in the SHARE projects is provided free of charge for scientific use globally, subject to European Union and national data protection laws as well as the publicly available Conditions of Use. As long as the data is available for everyone, there is not necessary to contact and chase permission from authors. However, should researchers need further information or understanding the process, Dr Fabio Franzese (one of the authors of the current study) can be contacted.

References

Vanleerberghe P, et al. The quality of life of older people aging in place: a literature review. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(11):2899–907.

Makovski TT, et al. Multimorbidity and quality of life: systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2019;53:100903.

Phyo AZZ, et al. Quality of life and mortality in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1596.

Howel D. Interpreting and evaluating the CASP-19 quality of life measure in older people. Age Ageing. 2012;41(5):612–7.

Marques LP, et al. Quality of life associated with handgrip strength and sarcopenia: EpiFloripa Aging Study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2019;81:234–9.

Stoner CR, Orrell M, Spector A. The psychometric properties of the control, autonomy, self-realisation and pleasure scale (CASP-19) for older adults with dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2019;23(5):643–9.

Veronese N, et al. Sarcopenia reduces quality of life in the long-term: longitudinal analyses from the English longitudinal study of ageing. Eur Geriatr Med. 2022;13(3):633–9.

Karim A, Muhammad T, Qaisar R. Prediction of Sarcopenia using multiple biomarkers of Neuromuscular Junction Degeneration in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. J Pers Med, 2021. 11(9).

Karim A, et al. Evaluation of Sarcopenia using biomarkers of the Neuromuscular Junction in Parkinson’s Disease. J Mol Neurosci. 2022;72(4):820–9.

Halaweh H. Correlation between Health-Related quality of life and hand grip strength among older adults. Exp Aging Res. 2020;46(2):178–91.

Qaisar R, et al. The coupling between sarcopenia and COVID-19 is the real problem. Eur J Intern Med. 2021;93:105–6.

Qaisar R, et al. Circulating MicroRNAs as biomarkers of Accelerated Sarcopenia in Chronic Heart failure. Glob Heart. 2021;16(1):56.

Karim A, et al. Elevated plasma zonulin and CAF22 are correlated with sarcopenia and functional dependency at various stages of Alzheimer’s diseases. Neurosci Res. 2022;184:47–53.

Jayasinghe UW, et al. Gender differences in health-related quality of life of australian chronically-ill adults: patient and physician characteristics do matter. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:102.

Börsch-Supan A. Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 8. Release version: 8.0.0. SHARE-ERIC. Data set; 2022.

Saari T, et al. Relationships between Cognition and Activities of Daily Living in Alzheimer’s Disease during a 5-Year Follow-Up: ALSOVA Study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;64(1):269–79.

Rizzoli R, et al. Quality of life in sarcopenia and frailty. Calcif Tissue Int. 2013;93(2):101–20.

Herman S, et al. Upper and lower limb muscle power relationships in mobility-limited older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(4):476–80.

Kawaharada R, et al. Impact of loss of independence in basic activities of daily living on caregiver burden in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a retrospective cohort study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2019;19(12):1243–7.

Giebel CM, Sutcliffe C, Challis D. Activities of daily living and quality of life across different stages of dementia: a UK study. Aging Ment Health. 2015;19(1):63–71.

Sallinen J, et al. Hand-grip strength cut points to screen older persons at risk for mobility limitation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(9):1721–6.

Gurley JM, et al. Enhanced GLUT4-Dependent glucose transport relieves nutrient stress in obese mice through changes in lipid and amino acid metabolism. Diabetes. 2016;65(12):3585–97.

Qaisar R, et al. ACE Inhibitors Improve Skeletal Muscle by Preserving Neuromuscular Junctions in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis; 2023.

Parvatiyar MS, Qaisar R. Editorial: skeletal muscle in age-related diseases: from molecular pathogenesis to potential interventions. Front Physiol. 2022;13:1056479.

Karim A, et al. Intestinal permeability marker zonulin as a predictor of sarcopenia in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2021;189:106662.

Laudisio A, et al. Muscle strength is related to mental and physical quality of life in the oldest old. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2020;89:104109.

Rodriguez-Blazquez C et al. Psychometric Properties of the CASP-12 scale in Portugal: an analysis using SHARE Data. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2020. 17(18).

Kang SY, Lim J, Park HS. Relationship between low handgrip strength and quality of life in korean men and women. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(10):2571–80.

Giovannini S et al. Neuropathic Pain in the Elderly. Diagnostics (Basel), 2021. 11(4).

Hadi MA, McHugh GA, Closs SJ. Impact of Chronic Pain on Patients’ quality of life: a comparative mixed-methods study. J Patient Exp. 2019;6(2):133–41.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research and Innovation, "Ministry of Education" in Saudi Arabia for funding this research (IFKSUOR3 - 003 - 1).

Funding

Prof. Shaea Alkahtani has received funding from the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia (IFKSUOR3-003-1). Dr Rizwan Qaisar has received a competitive (22010901121) grant from the University of Sharjah to support this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization; R.Q, M.H, & S.A. Data curation; M.H, & F.F. Formal analysis; M.H, & F.F. Funding acquisition; R.Q., A.A., S.M.A. & S.A. Investigation; R.Q, M.H, A.K, F.A, F.F, A.A., S.M.A. & S.A. Methodology; R.Q, M.H, A.K, F.A, F.F, & S.A. Project administration; R.Q, M.H, A.K, F.A, F.F, & S.A. Resources; R.Q, M.H, A.K, F.A, F.F, & S.A. Supervision; R.Q, M.H, A.K, F.A, F.F, & S.A. Validation; Writing – original draft; R.Q, M.H, A.K, F.A, F.F, & S.A. Writing – review & editing; R.Q, M.H, A.K, F.A, F.F, A.A., S.M.A. & S.A.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Each wave of SHARE was revised and approved by an ethics committee. This includes ethics issues of the survey itself as well as data protection regulations. In our study, we use SHARE wave 8 which was approved by the ethics board of Max-Planck-Society (Germany). Information and documentation on the ethics approval is available on the SHARE website (see FAQ Sect. 3.11 https://share-eric.eu/data/faqs-support.

The SHARE study is subject to continuous ethics review. During Waves 1 to 4, SHARE was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Mannheim. Wave 4 and the continuation of the project were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Council of the Max Planck Society. In addition, the country implementations of SHARE were reviewed and approved by the respective ethics committees or institutional review boards whenever this was required. The numerous reviews covered all aspects of the SHARE study, including sub-projects and confirmed the project to be compliant with the relevant legal norms and that the project and its procedures agree with international ethical standards. See also: https://share-eric.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/Ethics_Documentation/SHARE_ethics_approvals.pdf.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Qaisar, R., Hussain, M.A., Karim, A. et al. The quality of life in Alzheimer’s disease is not associated with handgrip strength but with activities of daily living–a composite study from 28 European countries. BMC Geriatr 23, 536 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04233-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04233-1