Abstract

Background

With modernization and ageing in China, the population of older adults living alone is increasing. Living alone may be a potential risk factor for depressive symptoms. However, no parallel mediation model analysis has investigated the mediating factors for living alone or not (living arrangements) and depressive symptoms.

Methods

This cross-sectional study included a total number of 10,980 participants from the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS), 1699 of whom lived alone and 9281 of whom did not live alone. Binary logistic regression and parallel mediation effect model were used to explore the relationship between living alone or not and depressive symptoms and possible mediation effects. Bootstrap analysis was used to examine the mediation effect of living alone or not on depressive symptoms.

Results

Compared to the participants who were not living alone, the living alone group had a higher rate of depressive symptoms. The binary logistic regression showed that after adjusting for other covariates, the risk of depressive symptoms was approximately 0.21 times higher for living alone compared to not living alone (OR = 1.21, 95% CI: 1.06, 1.37). Further, the results of the bootstrap analysis supported the partial mediating role of sleep quality and anxiety. Mediation analysis revealed that sleep quality and anxiety partially mediate the relationship between living alone and depressive symptoms (β = 0.008, 95% CI [0.003, 0.014]; β = 0.015, 95% CI [0.008, 0.024], respectively).

Conclusions

Sleep quality and anxiety were identified as partially parallel mediators between living alone or not and depressive symptoms. Older adults living alone with poorer sleep quality and more pronounced anxiety were positively associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms. Older adults living alone should be encouraged to engage in social activities that may improve sleep quality, relieve anxiety, and improve feelings of loneliness caused by living alone. Meanwhile, older adults living alone should receive attention and support to alleviate their depressive symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the results of the seventh national census in 2020, the number of Chinese over the age of 60 reached about 264.02 million, accounting for 18.70% of the total population [1]. Compared with the sixth national census, the proportion was above 5.44% points [2]. As the elderly population continues to grow, the health problems of older adults are increasing of public concern [3,4,5,6]. Due to various factors such as physical ageing, chronic diseases, declining social relationships, and economic status, older adults may have psychological problems related to negative emotions [7,8,9]. Depression is a prevalent mental health problem in older adults [10]. Depression mainly includes mood symptoms, neuropathic symptoms, and negative symptoms; depressed mood and lack of pleasure are the primary symptoms of depression [11]. It can lead to decreased interest in daily life activities, poor memory, etc. [12]. Research showed that associated factors with old-age depression include sex, chronic disease, cognitive impairment, functional impairment, etc. [13]. A systematic review evaluated the rate of depressive symptoms in Chinese older adults to be approximately 20.0% [14]. Therefore, research on depression in older adults has implications for identifying or improving depression in older adults.

With the modernization and demographic transition the traditional Chinese co-housing model is gradually changing [15]. The living arrangements of older adults in China have changed significantly [16]. The number of older adults who choose to live alone for active or passive reasons is increasing. Research demonstrated that older adults living alone have poorer health and mental health [17,18,19]. These unhealthy outcomes were regarded as cognitive decline, blood pressure, poorer physical health, anxiety and depression, etc. [20,21,22,23]. Older adults living alone felt more sad and hopeless [24], and empty-nest elderly have poorer physical health [25]. Research also indicated that older adults who lived alone were related to cognitive decline [26]. In addition, poor social network size was related to more obvious depressive symptoms in older adults living alone [27]. According to previous studies, we found that the relationship between living alone or not and depressive symptoms was obvious.

Sleep quality is another important issue in the lives of older adults living alone. The prevalence of sleep disorders in older adults was 10.4-62.1% [28]. Older adults and females were likely to have poor sleep quality [29]. Also, older adults living alone showed poorer sleep quality and female older adults who live alone had a higher poor sleep quality than those living with others [30]. Therefore, females, living alone and being older may likely have poorer sleep quality [31]. Scholars have pointed out that sleep quality was associated with depression, especially in elderly women living alone [32]. Other studies have also demonstrated the impact of sleep quality on depression [33,34,35]. Meanwhile, sleep quality played a mediating role between chronic diseases and depressive symptoms in the elderly [36]. Also, sleep quality served as a mediator between cognitive decline and depression in older adults [37]. Therefore, sleep quality may mediate depressive symptoms in older adults.

Anxiety, which is defined as a negative emotional state characterized by nervousness or anxiety, is another predominant mental health problem among older adults [38]. Anxiety symptoms were associated with depression in older adults living alone [39]. Previous study has shown that anxiety symptoms could mediate the association between loneliness and cognitive function among older adults [40]. However, no related research has addressed the possible mediating role of anxiety in the relationship between living alone or not and depressive symptoms. Therefore, we hypothesized that anxiety plays a role in the relationship between living alone or not and depressive symptoms.

Although previous researchers have shown the effects of depressive symptoms, sleep quality and anxiety in older adults living alone. Some studies have also explored the relationship between living arrangements and depression. Despite this, little research has been done on the mediating effects of sleep quality and anxiety between living alone or not and depressive symptoms. And it has not been investigated whether sleep quality and anxiety play a parallel mediating role in this effect. So this study aimed to investigate the relationship between living arrangements (living alone or not) and depressive symptoms in older adults and the parallel mediating role of sleep quality and anxiety in this relationship. We hypothesized that (1) the older adults living alone are more likely to have depressive symptoms; (2) sleep quality and anxiety could parallel mediate the relationship between living alone or not and depressive symptoms.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

The data were derived from the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS), which was a nationwide survey project of the Center for Healthy Aging and Development, National School of Development, Peking University [41]. The current study was the latest data of the CLHLS − 2018 wave. The data covered more than 500 sample sites in 22 of China’s 31 provinces, with more than 15,000 participants aged 65 and over [42].

The survey covered sociodemographic information, emotional characteristics, activities of daily living, health-related issues, economic status, etc. All data were obtained through face-to-face interviews. Participants were asked for sociodemographic information, including sex, age, residence, marital status, living arrangements and more. They were also asked about health-related issues, including self-reported health, sleep time, drinking, smoking and exercise habits, among other things. In addition, they were asked if they had chronic diseases. Economic status was also under investigation. Furthermore, the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-10) [43] and the Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) [44] assessed mental status, the Basic Activities of Daily Living (BADL) and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) [45] were considered as assessments of the activities of daily living.

This study used the CLHLS 2018 wave to investigate the depressive symptoms in older adults living alone or not and to analyze possible mediation effects. The inclusion criteria for this study were: (1) age > 65 years; (2) participants who were living with household member(s) and living alone. The exclusion criteria were: (1) participants who were living in a nursing institution; (2) among the variables of interest, samples with missing values(> 5%) or responses of “I don’t know/unable to answer” or extreme values. Mean imputation were used to replace missing values(< 5%). Finally, a total of 10,980 participants were included in this study. The detail of how to select participants was shown in Fig. 1.

Measures

Dependent variables

Depressive symptoms were evaluated by the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-10) [43]. The depression scale (CES-D-10) consisted of ten items using a four-point metric as 0 for “never”, 1 for “sometimes or rarely”, 2 for “often” and 3 for “always”. The score of CES-D-10 ranged from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating more pronounced depression. Individuals were considered to have depressive symptoms when they had a score of at least 10 [46]. Studies have shown that CES-D-10 has shown promising reliability among Chinese people [47]. The coefficient of Cronbach alpha for CES-D-10 in this study was 0.783. The internal consistency of the scale was reasonable.

Independent variables

Living arrangements (living alone or not) were evaluated using the question “Who do you live with?” which included the responses “with household members (not living alone)” and “living alone”.

Covariates

Covariates included sociodemographic characteristics, health-related issues, economic factors, activities of daily living and anxiety. The sociodemographic characteristics included age, gender, residence and marital status. Health-related issues included self-reported health (how do you feel about your health now?), sleep quality, social activities (do you take part in social activities?), sleep time (h)/day, smoking, drinking, exercises, number of chronic diseases (hypertension, dyslipidaemia, diabetes, cancer, heart attack, stroke, Parkinson’s disease, arthritis, etc.). Economic factors included sufficiency of living source (is all of the financial support sufficient to pay for daily expenses?), economic status (how do you rate your economic status compared with other local people?).

The anxiety disorder scale (GAD-7) was used to assess anxiety. GAD-7 measures the frequency of anxiety-related symptoms over the past two weeks and consists of seven items, each of which was answered by: 0 = never, 1 = a few days, 2 = more than half of the days, and 3 = almost every day. The total score ranged from 0 to 21. An individual with an anxiety score greater than 4 was defined as having anxiety [48]. It has been validated among older Chinese adults [49]. There was high internal consistency of the scale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.919) in this study.

The basic activities of daily living (BADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) were used to evaluate activities of daily living. BADL included six items, such as bathing, dressing, using the toilet, eating, etc. Each item was scored from 1 to 3 (1 = don’t need help; 2 = partially need help; 3 = need help). There was a range of scores from 6 to 18. The higher the score, the greater the BADL dependence. The BADL was defined as “need help” when “partially need help and need help” were chosen for at least one item. A Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.847 has been calculated for the BADL. IADL was about the instrumental activities which included eight items with each item scored from 1 to 3 (1 = complete independence; 2 = partial dependence; 3 = complete dependence) [50]. The IADL’s score ranged from 8 to 24. The higher the score, the greater the IADL dependence. The IADL was defined as “dependence” when “partially and complete dependence” were chosen for at least one item. The Cronbach alpha coefficient of the IADL was 0.945.

The details of the variable assignments were shown in Table 1.

Statistical analysis

Data were first analyzed by SPSS25.0 (IBM Corporation, NY, USA). The demographic characteristics were used as numbers and percentages or mean ± SD to express. Differences between groups were assessed by the Chi-square test (categorical data) and the t-test (continuous data). The association between living alone or not and CES-D-10 was then estimated using binary logistic regression with adjustment for confounding factors. In addition, GraphPad Prism 8 was used to draw the forest plots. Finally, Structural equation software Mplus 8.3 (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA, USA) [51] was used to test the mediation effect between living alone or not and depressive symptoms with mediating variables. The statistical significance level was P < 0.05.

Results

Participants

Of the 15,874 participants in the CLHLS 2018 wave, 574 were living in a nursing institution, 326 were missing values of independent variables. Meanwhile, in this article we defined living alone, which strictly means living by oneself but with no other household members. And we defined living with household members (not living alone), which strictly means living with somebody else. Therefore, 401 ambiguous values of living alone and 255 ambiguous values of not living alone were also excluded. And also, 2974 participants were excluded, which were samples with missing values(> 5%) or responses of “I don’t know/unable to answer” or extreme values. Finally, the final analysis was restricted to 10,980 individuals older than 65 years. (Fig. 1).

Basic characteristics and univariate analysis

As shown in Table 1, a total of 10,980 participants were selected for this study. The mean age was 83.63 ± 10.85 years old, 5134 (46.8%) males and 5846 (53.2%) females. 53.61% of the participants had depressive symptoms. Univariate analysis showed that gender, age, residence, marital status, living arrangements, self-reported health, sleep quality, social activities, sleep time (h)/day, smoking, drinking, exercises, number of chronic diseases, living source, economic status, BADL, IADL and anxiety had a statistically significant effect on depressive symptoms (P<0.05). The detailed data was presented in Table 1.

Association between living alone or not and depressive symptoms

A hierarchical multiple model of the binary logistic regression was used to estimate the association between living alone or not and depressive symptoms [52]. As shown in Table 2, Model 1 explored the association between living alone or not and depressive symptoms when adjusting for sociodemographic information about gender, age, marital status and residence. Compared with those who did not live alone, those who lived alone had a significantly increased risk of depressive symptoms (OR = 1.26, 95% CI: 1.12, 1.41) (Table 2, Supplementary Table 1). Model 2 was shown when adjusting for gender, age, marital status, residence, self-reported health, sleep quality, social activities, sleep time and smoking, drinking, exercises and number of chronic diseases, participants who lived alone had a significantly increased risk of depressive symptoms (OR = 1.20, 95% CI: 1.06, 1.36) (Table 2, Supplementary Table 2). Further adjusting for gender, age, marital status, residence, self-reported health, sleep quality, social activities, sleep time and smoking, drinking, exercises and number of chronic diseases, sufficiency of living source, economic status, BADL, IADL and anxiety, participants who lived alone had a significantly increased risk of depressive symptoms (Model 3 and Model 4) (Table 2, Supplementary Tables 3 and Supplementary Table 4). In the multivariable-adjusted model (Model 4), participants who lived alone had an increased risk of depressive symptoms (OR = 1.21, 95% CI: 1.06, 1.37) (Table 2). These results suggested that living arrangements were an essential predictor for depressive symptoms in older adults. In addition, the forest plot of Model 4 was shown in Fig. 2. The forest plot indicated the following factors may be likely facilitators for depressive symptoms in older adults: marital status, sleep quality, living arrangements, self-reported health, social activities, sufficiency of living source, economic status, IADL and anxiety.

The parallel mediation effect model

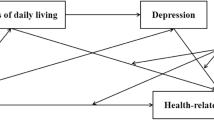

A parallel mediation model was used to test the likely mediation effect on the relationship between living alone or not and depressive symptoms. So a bootstrap test was carried out to verify the mediating effect of sleep quality and anxiety (Fig. 3). The results indicated that the mediating effect of sleep quality and anxiety on the relationship between living alone or not and depressive symptoms was significant. The total effect of living arrangements on depressive symptoms was significant (β = 0.089, 95% CI [0.065, 0.116], P < 0.001). The direct effect of living arrangements on depressive symptoms was significant (β = 0.048, 95% CI [0.031, 0.065], P < 0.001), accounting for 53.93% of the total effect. The indirect effect of living arrangements on depressive symptoms through sleep quality was significant (β = 0.008, 95% CI [0.003, 0.014], P < 0.01), accounting for 9% of the total effect. The indirect effect of living arrangements on depressive symptoms through anxiety was significant (β = 0.015, 95% CI [0.008, 0.024], P < 0.001), accounting for 17.3% of the total effect. Meanwhile, there was no significant difference in the mediating effect between sleep quality and anxiety (P = 0.091). The results demonstrated that both sleep quality and anxiety partially mediated the association between living alone or not and depressive symptoms. The detailed data was shown in Table 3

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between living arrangements (living alone or not) and depressive symptoms in older adults in China. Meanwhile, the possible effects and mediating roles of sleep quality and anxiety in this relationship were also estimated. Consistent with the hypothesis, people who lived alone were more likely to be depressed. Sleep quality and anxiety might act as a parallel mediating role between the relationship between living alone or not and depressive symptoms.

Negative mental states in older adults, such as depressive symptoms, have been a focus of researchers. Many factors could cause depressive symptoms in older adults such as loneliness [53, 54], health and social–physical environment [55], living alone [56], chronic diseases [57], etc. This study found that living alone was one of the risk factors for depressive symptoms. This was in accordance with previous evidence [58,59,60]. Meanwhile, the current study also showed that participants who lived alone had higher rates of depressive symptoms than those not living alone. Likewise, previous studies have linked social isolation to an increased risk of elevated depressive symptoms in older adults in Japan [61]. Similarly, studies have also shown that those without a spouse or living alone were more likely to suffer from depressive symptoms [62]. These all pointed to the need for older adults living alone should be noticed and cared for to improve their quality of life.

Binary logistic regression analysis showed that after adjusting for confounding factors, the relationship between living alone or not and depressive symptoms was still significant. This strongly suggested that living alone or not could be associated with depressive symptoms. By comparing Model 4, we considered that sleep quality and anxiety might have some mediating effect. So we further analyzed the possible mediating roles.

The mediation analysis showed that sleep quality was positively related to living alone or not and depressive symptoms, and partially mediated the effect of living alone or not on depressive symptoms. The older adults living alone had poorer sleep quality and were more prone to have depressive symptoms. It might be that loneliness is more pronounced in individuals who live alone which may lead to sleep disturbance and thus lead to possible depressive symptoms [63, 64]. This may be reflected in the release of dopamine in the brain, which has been shown to play a role in sleep regulation and emotion regulation [65]. While sleep disturbance may affect emotional functioning [66]. Meanwhile, research has shown that the dopamine regulatory system may underlie the pathophysiology of depression [67]. Therefore, effectively adjusting the sleep quality of older adults living alone can partially prevent the occurrence of depressive symptoms. This is similar to previous study which showed that depressive symptoms could be improved by improving sleep through physical exercise [68]. In addition, studies have shown that improving sleep quality could improve depressive symptoms and quality of life [33, 69].

The mediation analysis also showed that anxiety was positively related to living alone or not and depressive symptoms, and partially mediated the effect of living alone or not on depressive symptoms. The older adults living alone with obvious anxiety are more likely to have depressive symptoms. Older adults who live alone commonly experience feelings of loneliness [70], which can contribute to the development of anxiety [38]. And the appearance of anxiety may be associated with specific brain neurotransmitter mechanisms [71]. As two mental disorders, anxiety and depression often co-occur, but research also suggested that anxiety typically precedes depression [72]. Therefore, it is possible that anxiety serves as a risk factor in the association between living alone and depression. Related studies have also demonstrated that depression and anxiety as a role of Mediating effect on the relationship between loneliness and cognitive function [73]. In addition, outdoor activities were the moderation between living alone or not and depressive symptoms in older adults [59]. Also, research indicated that subjective physical health, resilience and social support were the mediators between loneliness and depression in older women [74]. Nevertheless, through a rigorous literature search, there was no relevant literature examining the parallel mediating role of sleep quality and anxiety in the relationship between living alone or not and depressive symptoms. This study provided evidence that sleep quality and anxiety are mediating factors in the association between living alone or not and depressive symptoms in older adults.

Therefore, older adults living alone should exercise more properly to improve their sleep quality. Also, they should engage in more social activities to relieve anxiety and loneliness. How to improve the sleep quality and anxiety of older adults living alone was also an issue that community workers needed to focus on and consider. First, mental health advocacy could be undertaken to improve the mental health of older adults living alone. Second, regular mental health counselling should be provided to older adults living alone to reduce the occurrence and development of negative mental states. Third, increasing companionship has a modest effect on improving the mental health of older adults living alone.

Our study had some strengths. First, this was the first study to identify sleep quality and anxiety as parallel mediators between living alone or not and depressive symptoms. Second, adjusting for a wide range of covariates allowed us to incorporate major potential confounders and better account for the association between living alone or not and depressive symptoms. Also, the study reflected some potential limitations. First of all, the data was a cross-sectional investigation, so the conclusion might only be explained by statistics [75]. Longitudinal data may be needed to explore this relationship further. Second, depressive symptoms in older adults might be associated with various factors, and our research might reflect in a few aspects. This study mainly considered psychosocial factors, so variables such as healthcare and dietary habits were not included. Third, this study used a screening instrument for depression. Therefore, the findings reflected only the relationship between living alone or not and depressive symptoms but not for depression. Fourth, variables were derived from self-report which might have led to bias [76]. Thus, more relevant studies are needed to provide evidence for the present findings.

Conclusions

The study investigated the association of living alone or not with depressive symptoms in older adults. After adjusting for many covariates, older adults who lived alone still had higher depressive symptoms. While the results of the parallel mediation analysis indicated that sleep quality and anxiety had a parallel mediating effect. Sleep quality and anxiety might explain the pathway from living arrangements to depressive symptoms. This might suggest a different approach to intervention strategies for depressive symptoms in older adults living alone. Older adults who lived alone with worse sleep quality and more pronounced anxiety were positively associated with higher depressive symptoms. Therefore, appropriate interventions should be implemented to reduce depressive symptoms in older adults who lived alone. Older adults who lived alone should be encouraged to engage in social activities that improve sleep quality, relieve anxiety, and improve feelings of loneliness caused by living alone.

Data availability

The CLHLS data were acquired from Peking University Open Research Data and are available at https://opendata.pku.edu.cn/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:https://doi.org/10.18170/DVN/WBO7LK. Permission for data use in this study was given by the CLHLS.

Abbreviations

- CLHLS:

-

Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey

- CES-D-10:

-

Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale

- GAD-7:

-

Anxiety Disorder Scale

- BADL:

-

Basic Activities of Daily Living

- IADL:

-

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

References

Liu Z, Agudamu, Bu T, Akpinar S, Jabucanin B. The Association between the China’s Economic Development and the passing rate of National Physical Fitness Standards for Elderly People aged 60–69 from 2000 to 2020. Front Public Health. 2022;10:857691. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.857691.

Tu WJ, Zeng X, Liu Q. Aging tsunami coming: the main finding from China’s seventh national population census. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2022;34(5):1159–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-021-02017-4.

Jensen JD. Health economic benefits from optimized meal services to older adults-a literature-based synthesis. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2021;75(1):26–37. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-020-00700-9.

Knight L, Hester M. Domestic violence and mental health in older adults. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2016;28(5):464–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2016.1215294.

Knapen J, Vancampfort D, Moriën Y, Marchal Y. Exercise therapy improves both mental and physical health in patients with major depression. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(16):1490–5. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2014.972579.

Srivastava S, Debnath P, Shri N, Muhammad T. The association of widowhood and living alone with depression among older adults in India. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):21641. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-01238-x.

Fuentecilla JL, Huo M, Birditt KS, Charles ST, Fingerman KL. Interpersonal tensions and Pain among older adults: the mediating role of negative Mood. Res Aging. 2020;42(3–4):105–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027519884765.

Bonilla-Sierra P, Vargas-Martínez AM, Davalos-Batallas V, Leon-Larios F, Lomas-Campos MD. Chronic Diseases and Associated factors among older adults in Loja, Ecuador. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114009.

Chen J, Zeng Y, Fang Y. Effects of social participation patterns and living arrangement on mental health of chinese older adults: a latent class analysis. Front Public Health. 2022;10:915541. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.915541.

Kiyoshige E, Kabayama M, Gondo Y, et al. Age group differences in association between IADL decline and depressive symptoms in community-dwelling elderly. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):309. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1333-6.

Malhi GS, Mann JJ, Depression. Lancet. 2018;392(10161):2299–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31948-2.

Su D, Zhang X, He K, Chen Y. Use of machine learning approach to predict depression in the elderly in China: a longitudinal study. J Affect Disord. 2021;282:289–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.160.

Kok RM, Reynolds CF 3rd. Management of Depression in older adults: a review. JAMA. 2017;317(20):2114–22. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.5706.

Tang T, Jiang J, Tang X. Prevalence of depressive symptoms among older adults in mainland China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;293:379–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.06.050.

Lu J, Zhang L, Zhang K. Care Preferences among Chinese older adults with Daily Care needs: individual and community factors. Res Aging. 2021;43(3–4):166–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027520939321.

Huang X, Liu J, Bo A. Living arrangements and quality of life among older adults in China: does social cohesion matter. Aging Ment Health. 2020;24(12):2053–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2019.1660856.

Han WJ, Li Y, Whetung C. Who we live with and how we are feeling: a study of Household living arrangements and subjective well-being among older adults in China. Res Aging. 2021;43(9–10):388–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027520961547.

Aranda L. Doubling up: a gift or a shame? Intergenerational households and parental depression of older Europeans. Soc Sci Med. 2015;134:12–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.03.056.

Song Q, Chen F, Living, Arrangements. Offspring Migration, and Health of older adults in Rural China: Revelation from biomarkers and propensity score analysis. J Aging Health. 2020;32(1):71–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264318804112.

Lee J, Lee AY. Home-visiting cognitive intervention for the Community-Dwelling Elderly living alone. Dement Neurocogn Disord. 2020;19(2):65–73. https://doi.org/10.12779/dnd.2020.19.2.65.

Nakashima T, Katayama N, Saji N, et al. Dietary habits and medical examination findings in japanese adults middle-aged or older who live alone. Nutrition. 2021;89:111268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2021.111268.

Beutel ME, Klein EM, Brähler E, et al. Loneliness in the general population: prevalence, determinants and relations to mental health. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):97. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1262-x.

Robb CE, de Jager CA, Ahmadi-Abhari S, et al. Associations of Social isolation with anxiety and Depression during the early COVID-19 pandemic: a survey of older adults in London, UK. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:591120. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.591120.

Yu CY, Hou SI, Miller J. Health for older adults: the role of Social Capital and Leisure-Time Physical activity by living arrangements. J Phys Act Health. 2018;15(2):150–8. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2017-0006.

Zhu H, He L, Peng J, et al. Community social capital and the health-related quality of life among empty-nest elderly in western China: moderating effect of living arrangements. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22(1):685. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-04310-6.

Yu Y, Lv J, Liu J, Chen Y, Chen K, Yang Y. Association between living arrangements and cognitive decline in older adults: a nationally representative longitudinal study in China. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):843. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03473-x.

Sakurai R, Kawai H, Suzuki H, et al. Association of eating alone with Depression among older adults living alone: role of poor Social Networks. J Epidemiol. 2021;31(4):297–300. https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.JE20190217.

Deng M, Qian M, Lv J, Guo C, Yu M. The association between loneliness and sleep quality among older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Geriatr Nurs. 2023;49:94–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2022.11.013.

Wang Y, Li Y, Liu X, et al. Gender-specific prevalence of poor sleep quality and related factors in a chinese rural population: the Henan Rural Cohort Study. Sleep Med. 2019;54:134–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2018.10.031.

Chu HS, Oh J, Lee K. The relationship between living arrangements and Sleep Quality in older adults: gender differences. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(7). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073893.

Yue Z, Zhang Y, Cheng X, Zhang J. Sleep quality among the Elderly in 21st Century Shandong Province, China: a ten-year comparative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(21). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114296.

Jang S, Yang E. Sleep, physical activity, and sedentary behaviors as factors related to depression and health-related quality of life among older women living alone: a population-based study. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act. 2023;20(1):6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11556-023-00314-7.

Becker NB, Jesus SN, João K, Viseu JN, Martins R. Depression and sleep quality in older adults: a meta-analysis. Psychol Health Med. 2017;22(8):889–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2016.1274042.

Yu J, Rawtaer I, Fam J, et al. Sleep correlates of depression and anxiety in an elderly asian population. Psychogeriatrics. 2016;16(3):191–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyg.12138.

Chang KJ, Son SJ, Lee Y, et al. Perceived sleep quality is associated with depression in a korean elderly population. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;59(2):468–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2014.04.007.

Zhang C, Chang Y, Yun Q, et al. The impact of chronic diseases on depressive symptoms among the older adults: the role of sleep quality and empty nest status. J Affect Disord. 2022;302:94–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.01.090.

Liu X, Xia X, Hu F, et al. The mediation role of sleep quality in the relationship between cognitive decline and depression. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):178. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-02855-5.

Yu J, Choe K, Kang Y. Anxiety of older persons living alone in the community. Healthc (Basel). 2020;8(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8030287.

Hou B, Zhang H. Latent profile analysis of depression among older adults living alone in China. J Affect Disord. 2023;325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.12.154. :378 – 85.

Wang Q, Zan C, Jiang F, Shimpuku Y, Chen S. Association between loneliness and its components and cognitive function among older chinese adults living in nursing homes: a mediation of depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and sleep disturbances. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):959. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03661-9.

Cui S, Yu Y, Dong W, et al. Are there gender differences in the trajectories of self-rated health among chinese older adults? An analysis of the chinese longitudinal healthy longevity survey (CLHLS). BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):563. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02484-4.

Yao Y, Chen H, Chen L, et al. Type of tea consumption and depressive symptoms in chinese older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):331. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02203-z.

Cheng C, Bai J. Association between Polypharmacy, anxiety, and Depression among Chinese older adults: evidence from the chinese longitudinal healthy longevity survey. Clin Interv Aging. 2022;17:235–44. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S351731.

Cheng C, DU Y, Bai J. Physical multimorbidity and psychological distress among chinese older adults: findings from chinese longitudinal healthy longevity survey. Asian J Psychiatr. 2022;70:103022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2022.103022.

Aihemaitijiang S, Zhang L, Ye C, et al. Long-term high dietary diversity maintains good physical function in chinese Elderly: a Cohort Study based on CLHLS from 2011 to 2018. Nutrients. 2022;14(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14091730.

Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (center for epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). Am J Prev Med. 1994;10(2):77–84.

Chen H, Mui AC. Factorial validity of the Center for epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale short form in older population in China. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26(1):49–57. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610213001701.

Yang Q, Wu Z, Xie Y, et al. The impact of health education videos on general public’s mental health and behavior during COVID-19. Glob Health Res Policy. 2021;6(1):37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-021-00211-5.

Ding KR, Wang SB, Xu WQ, et al. Low mental health literacy and its association with depression, anxiety and poor sleep quality in chinese elderly. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2022;14(4):e12520. https://doi.org/10.1111/appy.12520.

Zhang Y, Xiong Y, Yu Q, Shen S, Chen L, Lei X. The activity of daily living (ADL) subgroups and health impairment among chinese elderly: a latent profile analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01986-x.

Yang S, Li J, Zhao D, et al. Chronic conditions, Persistent Pain, and psychological distress among the rural older adults: a path analysis in Shandong, China. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:770914. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.770914.

O’Byrne P, Vandyk A, Orser L, Haines M. Nurse-led PrEP-RN clinic: a prospective cohort study exploring task-shifting HIV prevention to public health nurses. BMJ Open. 2021;11(1):e040817. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040817.

Peerenboom L, Collard RM, Naarding P, Comijs HC. The association between depression and emotional and social loneliness in older persons and the influence of social support, cognitive functioning and personality: a cross-sectional study. J Affect Disord. 2015;182:26–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.04.033.

Lee SL, Pearce E, Ajnakina O, et al. The association between loneliness and depressive symptoms among adults aged 50 years and older: a 12-year population-based cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(1):48–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30383-7.

Park S, Smith J, Dunkle RE, Ingersoll-Dayton B, Antonucci TC. Health and Social-Physical Environment Profiles among older adults living alone: Associations with depressive symptoms. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2019;74(4):675–84. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbx003.

Stahl ST, Beach SR, Musa D, Schulz R. Living alone and depression: the modifying role of the perceived neighborhood environment. Aging Ment Health. 2017;21(10):1065–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2016.1191060.

Ma Y, Xiang Q, Yan C, Liao H, Wang J. Relationship between chronic diseases and depression: the mediating effect of pain. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):436. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03428-3.

Honjo K, Tani Y, Saito M, et al. Living alone or with others and depressive symptoms, and Effect Modification by Residential Social Cohesion among older adults in Japan: the JAGES Longitudinal Study. J Epidemiol. 2018;28(7):315–22. https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.JE20170065.

Xu R, Liu Y, Mu T, Ye Y, Xu C. Determining the association between different living arrangements and depressive symptoms among over-65-year-old people: the moderating role of outdoor activities. Front Public Health. 2022;10:954416. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.954416.

Ge L, Yap CW, Ong R, Heng BH. Social isolation, loneliness and their relationships with depressive symptoms: a population-based study. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(8):e0182145. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182145.

Inoue K, Haseda M, Shiba K, Tsuji T, Kondo K, Kondo N. Social isolation and depressive symptoms among older adults: a multiple Bias Analysis using a longitudinal study in Japan. Ann Epidemiol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2022.11.001.

Wang Z, Yang H, Zheng P, et al. Life negative events and depressive symptoms: the China longitudinal ageing social survey. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):968. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09119-0.

Widhowati SS, Chen CM, Chang LH, Lee CK, Fetzer S. Living alone, loneliness, and depressive symptoms among indonesian older women. Health Care Women Int. 2020;41(9):984–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2020.1797039.

Cho JH, Olmstead R, Choi H, Carrillo C, Seeman TE, Irwin MR. Associations of objective versus subjective social isolation with sleep disturbance, depression, and fatigue in community-dwelling older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2019;23(9):1130–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2018.1481928.

Radwan B, Liu H, Chaudhury D. The role of dopamine in mood disorders and the associated changes in circadian rhythms and sleep-wake cycle. Brain Res. 2019;1713:42–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2018.11.031.

Richards A, Kanady JC, Neylan TC. Sleep disturbance in PTSD and other anxiety-related disorders: an updated review of clinical features, physiological characteristics, and psychological and neurobiological mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020;45(1):55–73. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-019-0486-5.

Grace AA. Dysregulation of the dopamine system in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia and depression. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016;17(8):524–32. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2016.57.

Garfield V, Llewellyn CH, Kumari M. The relationship between physical activity, sleep duration and depressive symptoms in older adults: the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA). Prev Med Rep. 2016;4:512–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.09.006.

Black DS, O’Reilly GA, Olmstead R, Breen EC, Irwin MR. Mindfulness meditation and improvement in sleep quality and daytime impairment among older adults with sleep disturbances: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):494–501. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.8081.

OʼSúilleabháin PS, Gallagher S, Steptoe A, Loneliness L, Alone, Mortality A-C. The role of emotional and social loneliness in the Elderly during 19 years of Follow-Up. Psychosom Med. 2019;81(6):521–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000710.

Chellappa SL, Aeschbach D. Sleep and anxiety: from mechanisms to interventions. Sleep Med Rev. 2022;61:101583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101583.

Demyttenaere K, Heirman E. The blurred line between anxiety and depression: hesitations on comorbidity, thresholds and hierarchy. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2020;32(5–6):455–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2020.1764509.

McHugh Power J, Tang J, Kenny RA, Lawlor BA, Kee F. Mediating the relationship between loneliness and cognitive function: the role of depressive and anxiety symptoms. Aging Ment Health. 2020;24(7):1071–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2019.1599816.

Lim YM, Baek J, Lee S, Kim JS. Association between Loneliness and Depression among Community-Dwelling Older Women living alone in South Korea: the Mediating Effects of subjective Physical Health, Resilience, and Social Support. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(15). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159246.

Yue Z, Liang H, Gao X, et al. The association between falls and anxiety among elderly chinese individuals: the mediating roles of functional ability and social participation. J Affect Disord. 2022;301:300–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.01.070.

Zhao Y, Duan Y, Feng H, et al. Trajectories of physical functioning and its predictors in older adults: a 12-year longitudinal study in China. Front Public Health. 2022;10:923767. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.923767.

Acknowledgements

The authors greatly appreciate the data provided by the study entitled “Chinese Longitudinal Longevity Survey” (CLHLS) which was implemented by the Center for Healthy Aging and Development Studies of National School of Development at Peking University. The authors would like to thank all the co-researchers, reviewers and editors.

Funding

No financial support was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the article and approved the manuscript. MH conceived the idea, analyzed the data and wrote the original draft. KL provided technical support. CL edited and reviewed the manuscript. YW analyzed the data. ZG analyzed the data by software and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interest

All authors declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Table 1

. Binary logistic regression to estimate the relationship between living alone or not and depressive symptoms(Model 1). Supplementary Table 2. Binary logistic regression to estimate the relationship between living alone or not and depressive symptoms(Model 2). Supplementary Table 3. Binary logistic regression to estimate the relationship between living alone or not and depressive symptoms(Model 3). Supplementary Table 4. Binary logistic regression to estimate the relationship between living alone or not and depressive symptoms(Model 4).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, M., Liu, K., Liang, C. et al. The relationship between living alone or not and depressive symptoms in older adults: a parallel mediation effect of sleep quality and anxiety. BMC Geriatr 23, 506 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04161-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04161-0