Abstract

Background

Existing evidence links hearing loss to depressive symptoms, with the extent of association and underlying mechanisms remaining inconclusive. We conducted a cross-sectional study to examine the association of hearing loss with depressive symptoms and explored whether social isolation mediated the association.

Methods

Eight thousand nine hundred sixty-two participants from Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study were included. Data on self-reported hearing status, the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15), social isolation and potential confounders were collected by face-to-face interview.

Results

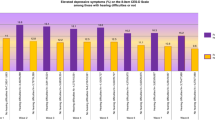

The mean (standard deviation) age of participants was 60.2 (7.8) years. The prevalence of poor and fair hearing was 6.8% and 60.8%, respectively. After adjusting for age, sex, household income, education, occupation, smoking, alcohol use, self-rated health, comorbidities, compared with participants who had normal hearing, those with poor hearing (β = 0.74, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.54, 0.94) and fair hearing (β = 0.59, 95% CI 0.48, 0.69) had higher scores of GDS-15. After similar adjustment, those with poor hearing (odds ratio (OR) = 2.13, 95% CI 1.65, 2.74) or fair hearing (OR = 1.68, 95% CI 1.43, 1.99) also showed higher odds of depressive symptoms. The association of poor and fair hearing with depressive symptoms attenuated slightly but not substantially after additionally adjusting for social isolation. In the mediation analysis, the adjusted proportion of the association mediated through social isolation was 9% (95% CI: 6%, 22%).

Conclusion

Poor hearing was associated with a higher risk of depressive symptoms, which was only partly mediated by social isolation. Further investigation of the underlying mechanisms is warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Depressive symptoms is the most common mental disorder in older people [1] and a leading cause of disability worldwide [2]. In China, the prevalence of depressive symptoms in people aged over 60 years was 22.7% [3]. Such high prevalence highlights the need for more effective preventive efforts.

Hearing loss is another common health problem in older people, leading to communication difficulties. In 2015, more than half of adults in China aged over 60 years were affected by hearing loss [4]. Hearing loss has been associated with many adverse health outcomes, such as social loneliness, disability, frailty and increasing mortality [5,6,7].

Moreover, existing evidence also links hearing loss to depression [8,9,10,11,12,13,14], although the results were not completely consistent (i.e., three studies showed no association [6, 15, 16]). An extensive systematic review and meta-analysis of 35 studies showed that hearing loss was associated with 47% higher risk of depression in older adults, albeit a high degree of heterogeneity (I2 = 83.26%) [17].

Hearing loss may lead to communication difficulties, and subsequent feelings of being emotionally isolated and social isolated [6, 18,19,20]. It has been shown that social isolation is one of risk factors for depression [21,22,23,24], and the association between hearing loss and depressive symptoms was attenuated after adjustment for social engagement [25]. Therefore, social isolation may mediate the association between hearing loss and depression. However, whether and the extent to which social isolation mediates the association of hearing loss and depressive symptoms remain to be examined.

Hence, we examined the association between hearing loss and depressive symptoms using data from the Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study (GBCS), a well-designed on-going population-based cohort study of older Chinese [26]. We also explored the possible mediating effect of social isolation on the association between hearing loss and depressive symptoms.

Methods

Study sample

GBCS is a three-way collaboration among the Guangzhou Twelfth People’s Hospital in Guangzhou and the University of Hong Kong in Hong Kong, China, and the University of Birmingham in UK. Details of the GBCS have been reported elsewhere [26]. Briefly, all participants were recruited from the Guangzhou Health and Happiness Association for the Respectable Elders (GHHARE), a large social and welfare organization. Guangzhou permanent residents aged 50 + years were eligible to participate and every member paid a monthly nominal fee of 4 RMB (about 0.57 USD). The GHHARE included about 7% of permanent Guangzhou residents in this age group, with branches over all districts of Guangzhou. All data were collected at Molecular Epidemiology Research Center in the Guangzhou Twelfth People’s Hospital during 2006–2008. Face-to-face interviews were conducted by full-time trained nurses. Physical examinations and laboratory assays were conducted by physicians and laboratory technicians in the hospital. The study was approved by the Guangzhou Medical Ethics Committee of the Chinese Medical Association. All participants provided written informed consent before participation.

Exposure

Information on hearing impairment was assessed by self-reports at baseline [27]. Participants were asked “how is your hearing without a hearing aid” and the responses included “excellent, good, fair, poor, or unable to hear”. Participants who reported “excellent” or “good” hearing were categorized as good hearing, and “poor” or “unable to hear” as poor hearing, and thus three groups (good, fair, and poor hearing) were used in data analysis.

Outcomes

Depressive symptoms were assessed by a previously validated Chinese version of the 15-item geriatric depression scale (GDS-15) [28]. The GDS-15 score ranges from 0 to 15, with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms [29]. The presence of depressive symptoms was defined by a GDS-15 score equals to or higher than 5 [30, 31].

Potential mediator

The potential mediator was social isolation. We used the Berkman-Syme Social Network Index (SNI) with appropriate revision [32, 33], which has been validated in Chinese population [34]: (1) Face-to-face contacts with co-inhabitants (including people who lived together); (2) Face-to-face contacts with co-inhabitants (excluding people who lived together); (3) Non-face-to-face contacts (by telephone/mail); or (4) club/organization contacts. We additionally included mail as another way of non-face-to-face contact besides telephone [33] to the Berkman-Syme Social Network Index (SNI), since both telephone and mail were common non-face-to-face contact ways in 2003, before smartphone, Internet, and social media had become popular. The four types of social isolation question and the scoring criteria for the composite social isolation score were shown in the Supplementary Table 1. A composite social isolation score was derived from the sum of 4 types of social isolation, with a score from 0 to 7. A higher score indicates more severe social isolation. The presence of social isolation was defined by a score of two or more.

Potential confounders

Potential confounders adjusted in the multivariable model were age, sex, socioeconomic position (occupation, education, household income), smoking [35, 36], alcohol use [36, 37], number of comorbidities [38, 39] and self-rated health [40, 41]. Occupation referred to the occupation that participants had for the longest period in their life. The presence of comorbidities was defined by presence of two or more chronic diseases: diabetes, hypertension, self-reported cancer and self-reported cardiovascular disease. Diabetes was defined by fasting plasma glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L or a self-reported medication history, and hypertension was defined by systolic blood pressure ≥ 130 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg, and/or taking anti-hypertensive medication [26].

Statistical analysis

Pearson chi-square test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to compare categorical and continuous variables between groups, respectively. Multivariable linear regression was used to assess the association between hearing loss and GDS-15 scores, reporting adjusted regression coefficient (β) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Logistic regression model was used to assess the association between hearing loss and the presence of depressive symptoms, giving odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI. Mediation analysis was conducted to assess the proportion of the association mediated through social isolation. The “medeff” package in Stata was used to perform mediation analysis. We also performed sensitivity analyses by (1) using different cutoff value of GDS-15 score for the definition of depressive symptoms, and (2) excluding those with hearing aids. Data analysis was done using STATA/SE 15.1.

Results

Of 10,088 participants recruited from 2006–2008, after excluding 1,126 (11.2%) participants with missing data, 8,962 participants (74.3% women) with complete data on all variables of interest were included in the current analysis.

Table 1 shows that mean age of the participants was 60.2 years, 74.3% were women, and the prevalence of hearing loss was 6.8%. Participants with poor hearing were older, had lower family income, lower education, and higher proportion of having manual occupation, fewer current alcohol users and more current smokers, higher prevalence of poor self-rated health, comorbidities and social isolation (P from 0.001 to 0.01). Those with poor hearing also had higher scores of GDS-15 and prevalence of depressive symptoms (both P < 0.001) (Table 1).

Table 2 shows that after adjusting for age, sex, household income, education, occupation, smoking, alcohol use, self-rated health, comorbidities, compared with participants who had normal hearing, those with fair hearing (β = 0.59, 95% CI: 0.48, 0.69) or poor hearing (β = 0.74, 95% CI: 0.54, 0.94) had higher scores of GDS-15. After similar adjustment, those with poor hearing (OR = 2.13, 95% CI: 1.65–2.74) or fair hearing (OR = 1.68, 95% CI: 1.43–1.99) also showed higher odds of depressive symptoms (Table 2). After additionally adjusting for social isolation, the associations of poor hearing and fair hearing with depressive symptoms attenuated slightly but not substantially, with the β (95% CI) for GDS-15 being 0.69 (0.50–0.89) and 0.58 (0.47–0.68), and the OR (95% CI) for depressive symptoms 2.05 (1.59–2.64) and 1.66 (1.41–1.97), respectively.

Table 3 shows that the association between poor hearing and depressive symptoms did not vary by sex, age group or education (P values for interaction from 0.38 to 0.97). Mediation analysis showed that the proportion of the association mediated through social isolation was 13% (95% CI: 0.10, 0.19) and the results remained after adjusting for potential confounders (9%, 95% CI: 0.06, 0.22) (Table not shown).

Sensitivity analyses using GDS-15 score of 8 or more as the cut-off point to define the presence of depressive symptoms showed similar results. Poor hearing was significantly associated with higher odds of depressive symptoms (adjusted OR = 1.78, 95% CI: 1.16–2.73) (Supplementary table 3). After excluding those who used hearing aids, the association of poor hearing with depressive symptoms appeared to be more pronounced (OR = 1.88, 95% CI: 1.22–2.89) (Supplementary table 4).

Discussion

Our study showed that hearing loss was independently associated with a higher risk of depressive symptoms, and the results did not vary by age, sex or education. The results attenuated slightly after adjustment for social isolation, indicating that other pathways might be involved. We also found that about 9% of the association could be explained by social isolation, highlighting the potential intervention approaches to prevent depression.

Our results that social isolation did not fully explain the association between poor hearing and depressive symptoms suggest further investigation to shed light on the exact mechanisms. We found a previous study showing the association between hearing loss and depressive symptoms attenuated and became non-significant after adjustment for social contact [25], while another two studies showing that the association remained significant after adjustment for social contact [42, 43]. Our results of subgroup analysis showed that the association was the strongest for those aged 60 to 69 years, but attenuated to the null in those aged over 70 years. As older people may have adapted to changes in their hearing status, with the communication skills changed or improved, the detrimental effects of hearing impairment on mental health maybe attenuated and the impact on social isolation might not be substantial [43]. Additionally, older people could use hearing aids to improve their hearing status and thus may alleviate the negative impacts induced by hearing loss [43]. However, our sensitivity showed similar results after excluding the participants using hearing aids. Future randomized controlled trials to confirm the effect of hearing aids use on improving mental health in older adults are warranted.

Neuropsychological mechanisms might underlie the association between hearing loss and depressive symptoms. For example, a decline in grey matter volume in temporal gyri, frontal gyri, primary auditory cortex and hypothalamus was found in neuroimaging studies on hearing loss [44,45,46,47]. Similar changes in cortical and subcortical was also observed in those with depression [48,49,50]. Besides, a study examining the effect of hearing loss on auditory and emotional networks found that amygdala and parahippocampal of participants with hearing loss showed decreased responses to emotional sounds [51]. However, the exact mechanisms are unclear. Further studies are needed to clarify the underlying pathophysiology of the association between hearing loss and depression.

Our findings further highlight the effect of hearing loss on depressive symptoms in older people as well as the pathway mediated through social isolation, which deserves further attention of clinician and audiologists. Audiologists or social healthcare workers are encouraged to provide emotional support and address the psychosocial needs for individuals with hearing loss, which might be helpful to improve mental health [52, 53]. However, despite the existing need by individuals with hearing loss, to date healthcare services for hearing-impaired individuals are mainly focused on treatment [54] and psychosocial support is rarely provided to them for coping with the social difficulties related to hearing loss [55]. This calls for effective interventions to tackle the issues related to increasing prevalence and detrimental impact of both social isolation and hearing loss.

Strengthens of our study included the large number of participants and a quantitative mediation analysis on social isolation. However, our study also had some limitations. First, causal inference could not be confirmed in the current study using cross-sectional analysis. Second, hearing status was classified by self-report. Further studies with hearing status measured by pure-tone audiometry are warranted [56, 57]. Third, we could not assess the association of hearing aids use with depressive symptoms because of the limited number of participants using hearing aids (n = 20). Fourth, our participants might not be fully representative to the general population due to the oversampling of women. Nevertheless, we adjusted for sex in the regression models as well as tested the interaction between hearing loss and sex, and we found no evidence that the associations varied by sex. Thus the unbalanced sex ratio might not be a major concern. Fifth, as our data were collected by interview, those with hearing difficulty might not be able to answer the questions correctly due to their poor hearing. However, as the interviews were conducted one-on-one and face-to-face by well-trained nurses using a computer-assisted questionnaire, the impact of hearing difficulty on hearing and answering the questions correctly was minimized.

In conclusion, our study showed that poor hearing was associated with a higher risk of depressive symptoms, and the association could not be fully explained by social isolation. Further investigation to shed light on the exact mechanisms behind this phenomenon is warranted. Health professionals and clinical practitioners are recommended to increase their awareness and understanding of depressive symptoms related to hearing status.

Availability of data and materials

Ethical approval in place allows us to share data on requests. Please directly send such requests to the Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study Data Access Committee (gbcsdata@hku.hk).

Abbreviations

- GDS-15:

-

The 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- GBCS:

-

Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study

- GHHARE:

-

Guangzhou Health and Happiness Association for the Respectable Elders

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- RMB:

-

Renminbi

- USD:

-

United States Dollar

- SNI:

-

Social Network Index

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- CNY:

-

Chinese Yuan

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- Ref:

-

Reference

References

Tang T, Jiang J, Tang X. Prevalence of depressive symptoms among older adults in mainland China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;293:379–90.

Friedrich MJ. Depression Is the Leading Cause of Disability Around the World. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;317(15):1517.

Zhang L, Xu Y, Nie H, Zhang Y, Wu Y. The prevalence of depressive symptoms among the older in China: a meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;27(9):900–6.

Gong R, Hu X, Gong C, Long M, Han R, Zhou L, Wang F, Zheng X. Hearing loss prevalence and risk factors among older adults in China. Int J Audiol. 2018;57(5):354–9.

Kamil RJ, Betz J, Powers BB, Pratt S, Kritchevsky S, Ayonayon HN, Harris TB, Helzner E, Deal JA, Martin K, et al. Association of Hearing Impairment With Incident Frailty and Falls in Older Adults. J Aging Health. 2016;28(4):644–60.

Pronk M, Deeg DJ, Smits C, van Tilburg TG, Kuik DJ, Festen JM, Kramer SE. Prospective effects of hearing status on loneliness and depression in older persons: identification of subgroups. Int J Audiol. 2011;50(12):887–96.

Engdahl B, Idstad M, Skirbekk V. Hearing loss, family status and mortality - Findings from the HUNT study. Norway Soc Sci Med. 2019;220:219–25.

Kim SY, Min C, Lee CH, Park B, Choi HG. Bidirectional relation between depression and sudden sensorineural hearing loss: Two longitudinal follow-up studies using a national sample cohort. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1482.

Pardhan S, Smith L, Bourne R, Davis A, Leveziel N, Jacob L, Koyanagi A, López-Sánchez GF. Combined Vision and Hearing Difficulties Results in Higher Levels of Depression and Chronic Anxiety: Data From a Large Sample of Spanish Adults. Front Psychol. 2020;11:627980.

Brewster KK, Hu MC, Zilcha-Mano S, Stein A, Brown PJ, Wall MM, Roose SP, Golub JS, Rutherford BR. Age-Related Hearing Loss, Late-Life Depression, and Risk for Incident Dementia in Older Adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2021;76(5):827–34.

Littlejohn J, Venneri A, Marsden A, Plack CJ. Self-reported hearing difficulties are associated with loneliness, depression and cognitive dysfunction during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Audiol. 2022;9(7):97–101.

Marmamula S, Kumbham TR, Modepalli SB, Barrenkala NR, Yellapragada R, Shidhaye R. Depression, combined visual and hearing impairment (dual sensory impairment): a hidden multi-morbidity among the elderly in Residential Care in India. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):16189.

Marques T, Marques FD, Miguéis A. Age-related hearing loss, depression and auditory amplification: a randomized clinical trial. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2022;279(3):1317–21.

Pardhan S, López Sánchez GF, Bourne R, Davis A, Leveziel N, Koyanagi A, Smith L. Visual, hearing, and dual sensory impairment are associated with higher depression and anxiety in women. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;36(9):1378–85.

Cosh S, Carriere I, Delcourt C, Helmer C, Consortium TS. A dimensional approach to understanding the relationship between self-reported hearing loss and depression over 12 years: the Three-City study. Aging Ment Health. 2021;25(5):954–61.

Mener DJ, Betz J, Genther DJ, Chen D, Lin FR. Hearing loss and depression in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(9):1627–9.

Lawrence BJ, Jayakody DMP, Bennett RJ, Eikelboom RH, Gasson N, Friedland PL. Hearing Loss and Depression in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Gerontologist. 2020;60(3):e137–54.

Mick P, Kawachi I, Lin FR. The association between hearing loss and social isolation in older adults. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;150(3):378–84.

Johnson B, Dawes P, Emsley R, Cruickshanks KJ, Moore DR, Fortnum H, Edmondson-Jones M, McCormack A, Munro KJ. Hearing Loss and Cognition: The Role of Hearing Aids, Social Isolation and Depression. PloS one. 2015;10(3):e0119616.

Keesom SM, Hurley LM. Silence, Solitude, and Serotonin: Neural Mechanisms Linking Hearing Loss and Social Isolation. Brain Sci. 2020;10(6):367.

Ge L, Yap CW, Ong R, Heng BH. Social isolation, loneliness and their relationships with depressive symptoms: A population-based study. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(8):e0182145.

Vargas I, Howie EK, Muench A, Perlis ML. Measuring the Effects of Social Isolation and Dissatisfaction on Depressive Symptoms during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Moderating Role of Sleep and Physical Activity. Brain Sci. 2021;11(11):1449.

Elmer T, Stadtfeld C. Depressive symptoms are associated with social isolation in face-to-face interaction networks. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1444.

Kotozaki Y, Tanno K, Sakata K, Takusari E, Otsuka K, Tomita H, Sasaki R, Takanashi N, Mikami T, Hozawa A, et al. Association between the social isolation and depressive symptoms after the great East Japan earthquake: findings from the baseline survey of the TMM CommCohort study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):925.

Kiely KM, Anstey KJ, Luszcz MA. Dual sensory loss and depressive symptoms: the importance of hearing, daily functioning, and activity engagement. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:837.

Jiang C, Thomas GN, Lam TH, Schooling CM, Zhang W, Lao X, Adab P, Liu B, Leung GM, Cheng KK. Cohort profile: The Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study, a Guangzhou-Hong Kong-Birmingham collaboration. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(4):844–52.

Mea D. Comparison between self-reported hearing and measured hearing thresholds of the elderly in China. Ear Hear. 2014;35(5):e228-232.

Jea W. The prevalence of depressive symptoms and predisposing factors in an elderly Chinese population. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994;89(1):8–13.

Mitchell AJ, Bird V, Rizzo M, Meader N. Diagnostic validity and added value of the Geriatric Depression Scale for depression in primary care: a meta-analysis of GDS30 and GDS15. J Affect Disord. 2010;125(1–3):10–7.

Lin QHJC, Lam TH, Xu L, Jin YL, Cheng KK. Past occupational dust exposure, depressive symptoms and anxiety in retired Chinese factory workers: the Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study. J Occup Health. 2014;56(6):444–52.

Ng TP, Niti M, Fones C, Yap KB, Tan WC. Co-morbid association of depression and COPD: a population-based study. Respir Med. 2009;103(6):895–901.

Berkman LF, Syme SL. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: a nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;109(2):186–204.

Wang J, Zhang WS, Jiang CQ, Zhu F, Jin YL, Cheng KK, Lam TH, Xu L. Associations of face-to-face and non-face-to-face social isolation with all-cause and cause-specific mortality: 13-year follow-up of the Guangzhou Biobank Cohort study. BMC Med. 2022;20(1):178.

Zhang Shuo CG. A study on the status and influencing factors of social isolation of the elderly in Chinese cities. Ren Kou Xue Kan. 2015;37(04):66–76.

Lee W, Chang Y, Shin H, Ryu S. Self-reported and cotinine-verified smoking and increased risk of incident hearing loss. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):8103.

Li Y, Zhang C, Ding S, Li J, Li L, Kang Y, Dong X, Wan Z, Luo Y, Cheng AS, et al. Physical activity, smoking, alcohol consumption and depressive symptoms among young, early mature and late mature people: A cross-sectional study of 76,223 in China. J Affect Disord. 2022;299:60–6.

Liang L, Hua R, Tang S, Li C, Xie W. Low-to-Moderate Alcohol Intake Associated with Lower Risk of Incidental Depressive Symptoms: A Pooled Analysis of Three Intercontinental Cohort Studies. J Affect Disord. 2021;286:49–57.

Basso L, Boecking B, Brueggemann P, Pedersen NL, Canlon B, Cederroth CR, Mazurek B. Subjective hearing ability, physical and mental comorbidities in individuals with bothersome tinnitus in a Swedish population sample. Prog Brain Res. 2021;260:51–78.

Leung JFV, Mahadevan R. How do different chronic condition comorbidities affect changes in depressive symptoms of middle aged and older adults? J Affect Disord. 2020;272:46–9.

Liu S, Qiao Y, Wu Y, Shen Y, Ke C. The longitudinal relation between depressive symptoms and change in self-rated health: A nationwide cohort study. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;136:217–23.

Anderle P, Rech RS, Baumgarten A, Goulart BNG. Self-rated health and hearing disorders: study of the Brazilian hearing-impaired population. Cien Saude Colet. 2021;26(suppl 2):3725–32.

Keidser G, Seeto M. The Influence of Social Interaction and Physical Health on the Association Between Hearing and Depression With Age and Gender. Trends Hear. 2017;21:2331216517706395.

Cosh S, von Hanno T, Helmer C, Bertelsen G, Delcourt C, Schirmer H. Group SE-C: The association amongst visual, hearing, and dual sensory loss with depression and anxiety over 6 years: The Tromso Study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33(4):598–605.

Peelle JE, Troiani V, Grossman M, Wingfield A. Hearing loss in older adults affects neural systems supporting speech comprehension. J Neurosci. 2011;31(35):12638–43.

Eckert MA, Cute SL, Vaden KI Jr, Kuchinsky SE, Dubno JR. Auditory cortex signs of age-related hearing loss. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2012;13(5):703–13.

Boyen K, Langers DR, de Kleine E, van Dijk P. Gray matter in the brain: differences associated with tinnitus and hearing loss. Hear Res. 2013;295:67–78.

Husain FT, Medina RE, Davis CW, Szymko-Bennett Y, Simonyan K, Pajor NM, Horwitz B. Neuroanatomical changes due to hearing loss and chronic tinnitus: a combined VBM and DTI study. Brain Res. 2011;1369:74–88.

Hickie I, Naismith S, Ward P, Turner K, Scott E, Mitchell P, Parker G. Reduced hippocampal volumes and memory loss in patients with early- and late-onset depression. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;186(3):197–202.

Gotlib IH, Hamilton JP. Neuroimaging and depression: Current status and unresolved issues. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2008;17(2):159–63.

Videbech P, Ravnkilde B. Hippocampal volume and depression: a meta-analysis of MRI studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(11):1957–66.

Husain FT, Carpenter-Thompson JR, Schmidt SA. The effect of mild-to-moderate hearing loss on auditory and emotion processing networks. Front Syst Neurosci. 2014;8:10.

Bennett RJ, Barr C, Cortis A, Eikelboom RH, Ferguson M, Gerace D, Heffernan E, Hickson L, van Leeuwen L, Montano J, et al. Audiological approaches to address the psychosocial needs of adults with hearing loss: perceived benefit and likelihood of use. Int J Audiol. 2021;60(sup2):12–9.

Heffernan E, Withanachchi CM, Ferguson MA. ‘The worse my hearing got, the less sociable I got’: a qualitative study of patient and professional views of the management of social isolation and hearing loss. Age and Ageing. 2022;51(2):afac019.

Bennett RJ, Saulsman L, Eikelboom RH, Olaithe M. Coping with the social challenges and emotional distress associated with hearing loss: a qualitative investigation using Leventhal’s self-regulation theory. Int J Audiol. 2022;61(5):353–64.

Bennett RJ, Meyer CJ, Ryan BJ, Eikelboom RH. How Do Audiologists Respond to Emotional and Psychological Concerns Raised in the Audiology Setting? Three Case Vignettes Ear Hear. 2020;41(6):1675–83.

Saito H, Nishiwaki Y, Michikawa T, Kikuchi Y, Mizutari K, Takebayashi T, Ogawa K. Hearing handicap predicts the development of depressive symptoms after 3 years in older community-dwelling Japanese. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(1):93–7.

Tambs K. Moderate effects of hearing loss on mental health and subjective well-being: results from the Nord-Trondelag Hearing Loss Study. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(5):776–82.

Acknowledgements

The Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study investigators include the following: Guangzhou No. 12 Hospital: WS Zhang, M Cao, T Zhu, B Liu, CQ Jiang (Co-PI); The University of Hong Kong: CM Schooling, SM McGhee, GM Leung, R Fielding, TH Lam (Co-PI); The University of Birmingham: P Adab, GN Thomas, KK Cheng (Co-PI).

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (81941019). The Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study was funded by The University of Hong Kong Foundation for Educational Development and Research (SN/1f/HKUF-DC; C20400.28505200), the Health Medical Research Fund (Grant number: HMRF/13143241) in Hong Kong; Guangzhou Public Health Bureau (201102A211004011) Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong (2018A030313140), and the University of Birmingham, UK.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HH, JW, LX, CQJ, WSZ, FZ, YLJ, and TZ have substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of funding, and data and interpretation of data; HH analyzed the data and drafted the article; JW, LX, and WSZ revised it critically for important intellectual content. WSZ and LX are the guarantors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Guangzhou Medical Ethics Committee of the Chinese Medical Association approved the study (ethics approval ID: 2021047), and all participants gave written, informed consent before participation. All procedures were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Supplementary Table 1. The four types of social isolation question and thescoring criteria for the composite social isolation score. Supplementary Table2. The Chinese version of four types of social isolation question and thescoring criteria for the composite social isolation score. Supplementary Table3. Associationof hearing loss with depressive symptoms (GDS-15 score ≥8). Supplementary Table4. Association of hearingloss with depressive symptoms after excluding participants with hearing aids (n=20).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, H., Wang, J., Jiang, C.Q. et al. Hearing loss and depressive symptoms in older Chinese: whether social isolation plays a role. BMC Geriatr 22, 620 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03311-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03311-0