Abstract

Background

To review the validated instruments that assess gait, balance, and functional mobility to predict falls in older adults across different settings.

Methods

Umbrella review of narrative- and systematic reviews with or without meta-analyses of all study types. Reviews that focused on older adults in any settings and included validated instruments assessing gait, balance, and functional mobility were included. Medical and allied health professional databases (MEDLINE, PsychINFO, Embase, and Cochrane) were searched from inception to April 2022. Two reviewers undertook title, abstract, and full text screening independently. Review quality was assessed through the Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for Systematic Reviews (ROBIS). Data extraction was completed in duplicate using a standardised spreadsheet and a narrative synthesis presented for each assessment tool.

Results

Among 2736 articles initially identified, 31 reviews were included; 11 were meta-analyses. Reviews were primarily of low quality, thus at high risk of potential bias. The most frequently reported assessments were: Timed Up and Go, Berg Balance Scale, gait speed, dual task assessments, single leg stance, functional Reach Test, tandem gait and stance and the chair stand test. Findings on the predictive ability of these tests were inconsistent across the reviews.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we found that no single gait, balance or functional mobility assessment in isolation can be used to predict fall risk in older adults with high certainty. Moderate evidence suggests gait speed can be useful in predicting falls and might be included as part of a comprehensive evaluation for older adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Over one-third of adults aged 65 years and older fall at least once a year [1]. Increasing age, frailty, comorbidity, impaired gait, muscle weakness, and impaired balance all contribute to the risk of falls [2]. Falls are a major cause of disability and constitute the leading cause of injury-related mortality in people aged above 75 years [3]. The importance of an individualised approach to screening, assessment, and intervention is emphasised across professional guidelines such as the Steadi Algorithm [4]. There is no clear consensus on the specific choice of fall assessment; however, professional guidelines state that adults at high risk should be able to access individually tailored multifactorial measures based on a comprehensive assessment [5, 6]. This should include assessment of gait, balance, and motor function with targeted interventions to address any limitation since these domains are associated with an increased risk of falls [7, 8]. Assessing these limitations could help to identify older adults at risk of falling and allow targeted intervention to reduce this risk.

Multiple approaches to assess gait, balance, and functional mobility have been developed including the Berg Balance Scale (BBS), the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test, and gait speed testing, such as the dual-task gait test. Although widely used across clinical practice, there appears to be little standardisation and difficulty determining the most appropriate tool [9]. Systematic reviews of individual tools have provided limited and conflicting evidence for a tool’s predictive ability, thus precluding the ability to make clear clinical recommendations [10,11,12,13]. To this end, we performed an umbrella review to synthesize the findings across multiple systematic reviews to help develop recommendations for clinical practice.

The aim of this umbrella review was to systematically review, critically appraise, and summarize the existing reviews on the use of assessment tools of gait, balance, and functional mobility to predict falls in older adults or distinguish fallers from non-fallers. This review is part of a larger initiative on behalf of the task force on global guidelines for falls in older adults (details available at https://worldfallsguidelines.com/) [14]. This paper presents a summary of the umbrella review for Working Group 1, and the findings will be fed into a wider consensus development process to develop key recommendations in the assessment and management of falls for older adults.

Methods

This umbrella review is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) [15] and the protocol was previously registered on PROSPERO’s international online register of systematic-, rapid-, and umbrella reviews (PROSPERO CRD42020225101).

Search strategy

The electronic academic databases MEDLINE, PsychINFO, Embase, and the Cochrane database for Systematic Reviews were searched from inception to November 23rd, 2020. The searches search were then updated on April 20th, 2022. To ensure a broad review of available literature, no restrictions on publication date were applied. A comprehensive search strategy was developed with the support of a research librarian using a combination of medical subject heading (MeSH) terms and key words for the concepts of older adults, gait, balance, and functional mobility assessments, and falls prediction. Only studies in English were included. The full search strategy for MEDLINE is presented in Additional file 1 at the end of this document and this strategy was adapted for each of the included databases. The reference lists of included papers were also reviewed to identify any further relevant reviews for inclusion.

Selection criteria

Types of studies

We included the following types of review studies:

-

Narrative reviews, defined as reviews that may or may not present a systematic synthesis of findings from all individual studies included [16];

-

Systematic reviews without meta-analysis, defined as having an explicit reproducible methodology including a systematic search that aims to identify all studies that meet pre-specified eligibility criteria followed by a systematic presentation and synthesis of the findings of all included studies [17];

-

Systematic reviews with meta-analysis, defined as systematic reviews using statistical techniques to combine and summarize the results of multiple studies [17].

We excluded the following types of studies: conference abstracts, student theses, books, book chapters, and papers reporting empirical data from a single study rather than reviewing more than one study. Reviews which included technology-based instruments only were excluded, as there is another on-going systematic review on this topic from Working Group 8 of the task force on global guidelines for falls in older adults (PROSPERO CRD42021241177).

Populations and settings

We included reviews of empirical studies in older adults (women and/or men), aged 60 years or older, in any setting. Specifically, we included reviews in all the following settings: the community, and primary and secondary care settings, including long-term care institutions, rehabilitation, and acute hospital settings. We also included reviews that presented data from various age groups in case they presented data on a subgroup of older adults aged 60 years or above separately. Following this, we excluded reviews examining individuals exclusively younger than 60 years of age.

Assessments

Reviews that included validated assessments of gait, balance, and functional mobility to predict falls or to distinguish fallers from non-fallers.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome of interest was the prediction of falls. Secondary outcomes were as follows: reliability, validity including sensitivity, specificity, feasibility, and cost of the assessments.

Study selection

Two reviewers (KR, DBJ) independently screened titles and abstracts of all records for eligibility, using the online software package Rayyan (https://www.rayyan.ai/). Disagreements were resolved by the assessment of a third reviewer (GO). Full text articles were retrieved and screened independently by two reviewers (KR, DBJ) with disagreements resolved by the assessment of a third reviewer (GO).

Data extraction

Three reviewers (KR, DBJ, GO) extracted the data by using a pre-defined data extraction form developed specifically for this review. The following data were extracted:

-

Review details: author(s), year of publication, country of lead author, type of participants, review objective, number of participants, age range of participants, mean age of participants, and proportion of women.

-

Search details: sources searched, type of analysis (narrative review, systematic review without meta-analysis, or systematic review with meta-analysis), number of studies included in the review, design of studies included, and countries in which included studies were conducted.

-

Critical appraisal: date range of included studies, critical appraisal tool(s) used in the review, and critical appraisal score.

-

Gait, balance, and functional mobility tests assessed: fall prediction outcome, measurement of falls, predictive ability, reliability, validity (specificity, and sensitivity).

-

Cost: any cost analysis conducted.

Risk of bias assessment

Three reviewers (KR, DBJ, GO) assessed the risk of bias of the included studies using the Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for Systematic Reviews (ROBIS) [18]. ROBIS assesses four domains: 1) study eligibility criteria; 2) identification and selection of studies; 3) data collection and study appraisal; and 4) synthesis and findings.

Data synthesis

To provide key clinical and research recommendations on assessment tools for fall prevention, the findings were synthesised for the most commonly reported gait, balance, and functional mobility assessments. Due to the heterogeneity of the reviews with regards to participant characteristics, settings, and assessment protocols, it was not appropriate to conduct a meta-analysis. A narrative synthesis was conducted for each gait, balance, and functional mobility assessment that was reported by more than two review studies. The narrative synthesis was conducted based on the review type and quality, as well as the number of reviews addressing this assessment and the key findings. For each review, the results were interpreted to indicate whether the findings in relation to the assessment tool’s predictive ability for falls were favourable, not favourable, inconsistent, or unclear (if data could not be extracted). An overall summary for each assessment was then made based on the highest quality available evidence. The synthesis is presented in tabular format; in the tables, the studies are ordered based on their quality.

Results

Search results

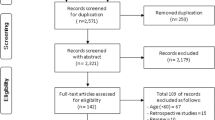

The literature search identified a total of 2736 potentially relevant records. Of these, 543 were duplicates. The titles and abstracts of the remaining 2213 records were screened. After excluding 2092 items in the screening, the full texts of 121 articles were assessed for eligibility. After excluding further 90 records (50 were not review papers; 18 did not assess falls; 9 were technology-based instruments only; 7 were duplicate records; 5 were not in older adults; and 1 was not in English), we included 31 records in our analyses. Figure 1 at the end of this document shows the PRISMA flow-chart.

PRISMA flow chart. Adapted From: Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(7): e1000097. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed1000097 For more information, visit www.prisma-statement

Characteristics of included reviews

Table 1 presents a summary of the 31 included review studies. Three were categorised as narrative reviews, 17 as systematic reviews without meta-analysis, and 11 were systematic reviews with meta-analyses. Nine reviews reported on community dwelling older adults only, one reported on long term care settings only, one reported on emergency department settings only, and 13 reported studies across a range of settings including community, supported living, residential care, outpatient and inpatient settings. Four reviews provided no details on settings. Three reviews reported that they included older adults with cognitive impairment. Healthy community-dwelling older people were the primary focus of reviews however older people with neurological disorders were included in one review [33], older people receiving inpatient stroke rehabilitation were included in one review [35], and older people being assessed in the emergency department was the focus of one review [27].

Risk of bias assessment in the included reviews

Of the 31 included reviews, ten were globally deemed at low risk of bias, eight at unclear risk of bias, and 13 at high risk of bias (Table 2). Areas of high or unclear risk of bias primarily related to limiting searches with language restrictions, selection and data extraction not done in duplicate, and a lack of quality appraisal of the individual studies.

Gait, balance, and functional mobility assessments

The most frequently reported gait, balance, and functional assessments for falls prediction included the following tests: TUG, BBS, tests of gait speed, dual task assessments, single leg stance, Functional Reach Test (FRT), tandem gait and the chair stand test.

Timed up and go

The TUG consists of a combination of standing from a chair and walking 3 m, turning and returning to sitting [45]. The TUG test was reported in thirteen reviews (Table 3). Three reviews demonstrated favourable findings [9, 12, 29], four reviews reported unclear or inconsistent findings [24, 26, 27, 35], five reviews demonstrated not favourable findings [10, 13, 20, 38, 42], and one review reported no extractable data on TUG’s ability to predict falls [19]. Across all review studies, the evidence was inconsistent on the ability of the TUG to predict falls. There is some evidence, however, from some subgroup analysis that the TUG may have a role in fall prediction for the lower functioning older adult population [13, 38].

Berg balance scale

The BBS is a balance test with a series of 14 balance tasks that assess a person’s ability to safely balance. Tasks include sitting-to-standing, turning 360 degrees and standing on one leg [46]. The BBS was reported in nine review papers (Table 4).

Three reviews demonstrated favourable findings [9, 12, 29], one review reported inconsistent findings [29], and four reviews demonstrated not favourable findings [11, 26, 33, 42], on the BBS ability to predict falls. One review did not report any results to extract [20]. Across all the review papers, the evidence for using the BBS to predict falls was inconsistent, and based on the best available evidence [11, 42], the use of the BBS as a balance assessment used in isolation is not recommended to predict falls. There was some evidence from one review that the BBS may have a predictive role in a stroke clinic population [29].

Gait speed

Gait speed is the measurement of the time it takes to complete a walk over a given distance in the participant’s preferred or maximum pace [47, 48] and was reported in ten review papers (Table 5). Seven reviews demonstrated positive findings [22, 26, 29, 30, 34, 35, 41]. One reported low sensitivity on the ability of gait speed to predict falls in community dwelling older adults [29], and one reported that a timed walk was not an independent predictor of falls in long term care settings [35]. One review reported that gait speed did not predict falls in cognitive impaired older adults, however a subgroup analysis showed evidence for gait speed predicting falls [38]. One review reported no data to extract [19]. Different distances were used across the studies including 4, 6, 10, and up to 25 m distances. Two reviews investigated usual gait speed [22, 34]. One review reported mainly preferred walking speed [41]. One review reported that of the eight studies that assessed gait speed, six found slow gait speed under standard conditions to predict falls [38].

Details on the gait speed protocol was lacking in three reviews [19, 26, 35]. The best available evidence suggested that gait speed was a useful measure in predicting falls in community dwelling older adults.

Dual task assessments

Dual task assessments are the combination of a physical task (such as walking) and either a second physical task (such as holding an object) or a cognitive task (such as counting) [49] and was reported in seven review papers (Table 6). In detail, four reviews demonstrated favourable findings [24, 32, 41], two review reported unclear findings [23, 37], and one review demonstrated not favourable findings on the ability of dual task testing to predict falls [36]. Evidence for the ability of dual task testing to predict falls over single balance tests was inconsistent; however, the best available evidence suggested that dual task testing had the ability to predict falls. The optimal type of dual task test is still unclear.

Single leg stance

The single leg stance test is a single leg standing balance test [50] and was reported in five reviews (Table 7). One review reported favourable findings [39]. Three reviews reported unclear findings on its ability to predict falls [9, 40, 42] and one review demonstrated not favourable findings [31]. Overall, the evidence was inconsistent for the ability of the single leg stance to predict falls.

Functional reach test

The Functional Reach Test is a functional balance test [51] and was reported in nine review papers (Table 8). Six review papers demonstrated favourable findings [9, 20, 26, 31, 35, 39], and three reported not favourable findings on the ability of the Functional Reach Test to predict falls [40, 42, 43]. The evidence across all the reviews was inconsistent for the predictive ability of the Functional Reach Test.

Tinetti/ performance-oriented mobility assessment (poma)

The Tinetti test and the POMA test are task-oriented balance tests [52] and were reported in eight review papers (Table 9). Two review papers demonstrated positive findings [19, 38], five review papers reported unclear findings [12, 20, 26, 31, 42], and one review paper reported not favourable findings on the ability of the Tinetti test or POMA to predict falls [9]. There were inconsistent findings across all the reviews on the predictive ability of the Tinetti and POMA test.

Tandem gait and stance

Tandem gait and stance is a standing balance test and a heel to toe walking test [53] and was reported in eight review papers (Table 10). One review paper demonstrated favourable findings in tandem stand [39]. Two review papers concluded that tandem walk was a significant predictor of falls [28, 42], and one review demonstrated that only tandem walk had the ability to predict falls [9]. Five review papers reported unclear associations [9, 26, 35, 40, 42], and one review reported that the test did not predict falls [27]. The findings across the reviews were inconsistent on the ability of the tandem gait to predict falls. However, tandem walk showed promising results in selecting the population in need of a further evaluation [ref].

Chair stand test (cst)

The CST measures the ability to get up from chair without using arms, time taken to get up five times, or number of chair stands over 30 seconds, and was reported in five review papers (Table 11). One review paper demonstrated favourable results [9], 3 papers reported unclear results [19, 35, 38],, and one review reported inconsistent findings on the ability of the CST to predict falls [39]. Overall, the evidence was inconsistent for the ability of CST to predict falls.

Discussion

Summary

This umbrella review aimed to systematically and critically appraise the evidence on gait, balance, and functional mobility assessments used to predict falls for older adults. A total of 31 review papers were identified, which were mainly systematic reviews without meta-analysis and of low quality with high risk of bias. There were inconsistencies in the findings across all the review papers. The present umbrella review determined that there is not one single gait, balance, and functional mobility assessment that can be used in isolation to predict falls in community-dwelling older adults. The TUG was the most frequently assessed single test for falls prediction, but the findings were inconsistent in its ability to predict falls. There is, however, favourable evidence to suggest that gait speed can be useful in predicting falls and might be included as part of a comprehensive evaluation for older adults. Some positive results were found in dual task assessment as predictors of falls.

Wider context

Clinical practice guidelines recommend multifactorial interventions to prevent falls in community dwelling older adults who are at an increased risk of falls [6, 14, 54, 55]. Such interventions contain an initial assessment of risk factors for falls and subsequent customised interventions for each patient based on risk factors [56]. The inconsistencies reported across the included review papers highlight the importance of making a clinical judgement including risk factors such as previous falls, cognitive impairment, comorbidity, polypharmacy, activities of daily living, psychological factors, vision impairment, cognitive impairment, and footwear [1, 2].

Clinicians are encouraged to consider individual needs and contexts when evaluating falls risk in older adults. The inconsistencies reported across the review papers of the present umbrella review may have been influenced by the wide range of settings and clinical characteristics included in the individual studies. It is thus challenging to make recommendations for specific settings using the evidence from this review, in light of the degree of heterogeneity across the evidence available. Based on the evidence from this review, we are unable to recommend using the Timed Up and Go, Berg Balance Scale, Chair Stand Test, One Leg Stand, or Functional Reach, alone as single tests for the prediction of falls in older adults. We acknowledge however that these tests have value in assessing mobility and balance limitations and in identifying appropriate targeted interventions.

In post stroke patients, one review reported positive results on the BBS for fall prediction [29], whereas the Functional Reach Test showed positive results in populations with cognitive impairments [26].

Gait speed appeared most promising in fall prediction and has also been associated with other important outcomes like survival and functional capacity [22]. Gait speed is a simple measurement, with no need for expensive equipment and can be performed quickly. The favourable findings in this review indicate gait speed is feasible to complete for community-dwelling older people and older outpatients of stroke clinics. However, gait speed should be assessed through a clearly defined protocol, which specifies the distances to walk or the time allocated to walking, and whether participants walk at their usual speed or maximum speed. One review suggested that the assessment at usual pace gait speed over 4 m might represent a highly reliable instrument to be implemented [22]. Given the number of older people who could benefit from fall risk assessment, an inexpensive assessment tool that can be used in different settings is appealing.

Dual task assessments showed promise in its ability to predict falls, with some evidence suggesting that it was a better predictor of falls than single task assessments [32]. But importantly, differences in testing protocols could have influenced the results, warranting future research with standardised protocols to allow further synthesis of this finding.

The findings from the present umbrella review demonstrate that it is feasible to complete an assessment of gait speed in older adults across a range of settings including the community, long-term care institutions, and rehabilitation settings. Based on the assessment of the falls risk, it is important that interventions are offered to reduce this risk. Exercise programmes have been demonstrated to reduce the rate of falls, particularly for community-dwelling older adults; the most effective programmes include balance and functional mobility exercises [57].

The TUG was the most frequently reported assessment for falls prediction. The TUG is a simple and low-cost test that is easy to administer and has been previously recommended in clinical practice guidelines including the guidelines posited by the American Geriatrics Society/British Geriatrics Society (AGS/BGS) [54, 58]. However, this umbrella review demonstrated that its fall predictive ability was inconsistent. This inconsistency may be explained by heterogeneity in the settings and populations studied, the use of different cut-off times, and the mixed quality of the evidence. One review suggested that the TUG may have a role in predicting falls in lower functioning or institutionalized older adults [13].

Strengths and limitations

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first umbrella review examining gait, balance, and functional mobility assessments in the prediction of falls for older adults. Further strengths of this umbrella review included following PRISMA reporting guidelines [15], conducting a comprehensive search for evidence with the support of a research librarian, and clearly stating the objectives beforehand and ensuring transparency with the published protocol. Furthermore, the selection of the included studies was performed in duplicate with a third reviewer resolving any conflicts. The reviewers assessed the quality of the included studies in pairs, using a quality assessment tool designed specifically to assess the risk of bias in systematic reviews, and differences were discussed and resolved between reviewers.

However, this umbrella review has some limitations. The included studies were too heterogeneous to allow for direct comparison of results in a united meta-analysis. In addition, studies involved both prospectively and retrospectively reported falls, which might have contributed to some of the heterogeneity. Also, many of the included review studies were considered to have a high or unclear risk of bias with a lack of clear reporting. This limited the data that could be extracted and synthesised. The differences in the included studies were not statistically assessed, following advice from a statistician that it was not possible to do so, due to heterogeneity between studies. We excluded review papers that were not available in English due to the resources available for the review, therefore, it is possible that the language restriction in the selection of the included studies may have affected the results by introducing a risk of selection bias. We chose to exclude grey literature (e.g., papers that are not published in peer-reviewed journals) to ensure a certain level of quality in the included studies. In this umbrella review no differentiation between falls, multiple fallers or injurious falls were made.

It was not possible from the umbrella review to provide guidance on the critical level of performance in gait speed associated with higher risk of falling. The optimal cut-off in gait speed to predict falls has not been universally defined and accepted, although different cut-offs (eg 1 m/s, 0.8 m/s, 0.6 m/s) have been associated with various adverse health outcomes, including falls. Based on a systematic literature review, an International Academy on Nutrition and Ageing (IANA) expert panel advised to assess GS at usual pace over 4 m and to use the easy-to-remember cut-off point of 0.8 m/s to predict the risk of adverse outcomes [22].

The Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) was included in the search terms for this review; however, it was only reported in one review [26], limiting the ability to draw conclusions about its predictive ability in this review. In 2018, the SPPB has been accepted by the European Medical Agency as an assessment tool to assess frailty. In addition, as the SPPB is widely used in geriatric and other medical fields, it is gaining importance. Single studies reported mixed results with regards to fall prediction [59, 60]. Therefore, future research investigating its ability to predict falls and injurious falls is urgently needed.

Further studies are required to investigate the applicability and validity of fall risk assessment tests in different populations with varying functional levels. Different frailty or intrinsic capacity status may influence the fall predictive ability of these tests. Older frailer adults with cognitive or physical impairment may not be able to perform hazardous tasks or follow complex instructions. Low resource settings may lack the equipment and trained staff to perform the more sophisticated tests, despite their potential effectiveness.

We acknowledge that assessing gait, balance, and functional mobility may form only one part of an assessment of falls prediction. Falls prediction approaches may need to further account for the multifactorial nature of falls and the extensive list of factors that can contribute to the risk of falling. The development of multifactorial falls prediction models is an area of ongoing research; however, further work is required before their widespread use is advocated [61].

Conclusions

Overall, there is not one single gait, balance, and functional mobility assessment alone that can be used in isolation to predict fall risk in community-dwelling older adults. The best available evidence suggests that gait speed is a useful measure in predicting falls and should be considered as part of a comprehensive evaluation of fall risk for older adults. We found that dual task assessments demonstrate some potential to predict falls in older adults, warranting further research in this area.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

05 October 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03352-5

Abbreviations

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- BBS:

-

Berg Balance Scale

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- FRT:

-

Functional Reach Test

- MD:

-

Mean Difference

- n:

-

number of included studies,

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- POMA:

-

Performance-Oriented Mobility Assessment

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PoTP:

-

Posttest probability test

- ROBIS:

-

Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for Systematic Reviews

- SLS:

-

Single Leg Stance

- SROC:

-

Summary receiver operating characteristic,

- TUG:

-

Timed up and go test

References

Lord SR, Ward JA, Williams P, Anstey KJ. An epidemiological study of falls in older community-dwelling women: the Randwick falls and fractures study. Aust J Public Health. 1993;17(3):240–5.

Tinetti ME, Speechley M, Ginter SF. Risk factors for falls among elderly persons living in the community. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(26):1701–7.

Scuffham P, Chaplin S, Legood R. Incidence and costs of unintentional falls in older people in the United Kingdom. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(9):740–4.

Stevens JA, Phelan EA. Development of STEADI: a fall prevention resource for health care providers. Health Promot Pract. 2013;14(5):706–14.

Blain H, Masud T, Dargent-Molina P, et al. A comprehensive fracture prevention strategy in older adults: the European Union Geriatric Medicine Society (EUGMS) statement. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2016;28(4):797–803.

NICE (2019) Surveillance of falls in older people: assessing risk and prevention (NICE guideline CG161). London. 2019. Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg161/resources/2019-surveillance-of-falls-in-older-people-assessing-risk-and-prevention-nice-guideline-cg161-pdf-8792148103909.

Shumway-Cook A, Baldwin M, Polissar NL, Gruber W. Predicting the probability for falls in community-dwelling older adults. Phys Ther. 1997;77(8):812–9.

Verghese J, Ambrose AF, Lipton RB, Wang C. Neurological gait abnormalities and risk of falls in older adults. J Neurol. 2010;257(3):392–8.

Lusardi MM, Fritz S, Middleton A, et al. Determining Risk of Falls in Community Dwelling Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Using Posttest Probability. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2017;40(1):1–36.

Barry E, Galvin R, Keogh C, Horgan F, Fahey T. Is the Timed Up and Go test a useful predictor of risk of falls in community dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14:14.

Lima CA, Ricci NA, Nogueira EC, Perracini MR. The Berg Balance Scale as a clinical screening tool to predict fall risk in older adults: a systematic review. Physiotherapy. 2018;104(4):383–94.

Park SH. Tools for assessing fall risk in the elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2018;30(1):1–16.

Schoene D, Wu SM, Mikolaizak AS, et al. Discriminative ability and predictive validity of the timed up and go test in identifying older people who fall: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(2):202–8.

Montero-Odasso M, van der Velde N, Alexander NB, Becker C, Blain H, Camicioli R, et al. Task Force on Global Guidelines for Falls in Older Adults. New horizons in falls prevention and management for older adults: a global initiative. Age Ageing. 2021;50(5):1499-1507. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afab076.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006–12.

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1.

Whiting P, Savovic J, Higgins JP, et al. ROBIS: A new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;69:225–34.

Ambrose AF, Cruz L, Paul G. Falls and Fractures: A systematic approach to screening and prevention. Maturitas. 2015;82(1):85–93.

Nakamura DM, Holm MB, Wilson A. Measures of balance and fear of falling in the elderly: a review. Phys Occup Ther Geriatr. 1999;15(4):17–32.

Stasny BMNR, LoCascio LV, Bedio N, Lauke C, Conroy M, Thompson A, et al. The ABC Scale and Fall Risk: A Systematic Review. Phys Occup Ther Geriatr. 2011;29(3):233–42.

Abellan van Kan G, Rolland Y, Andrieu S, et al. Gait speed at usual pace as a predictor of adverse outcomes in community-dwelling older people an International Academy on Nutrition and Aging (IANA) Task Force. J Nutr Health Aging. 2009;13(10):881–9.

Bayot M, Dujardin K, Dissaux L, et al. Can dual-task paradigms predict Falls better than single task? - A systematic literature review. Neurophysiol Clin. 2020;50(6):401–40.

Beauchet O, Fantino B, Allali G, Muir SW, Montero-Odasso M, Annweiler C. Timed Up and Go test and risk of falls in older adults: a systematic review. J Nutr Health Aging. 2011;15(10):933–8.

Di Carlo S, Bravini E, Vercelli S, Massazza G, Ferriero G. The Mini-BESTest: a review of psychometric properties. Int J Rehabil Res. 2016;39(2):97–105.

Dolatabadi E, Van Ooteghem K, Taati B, Iaboni A. Quantitative mobility assessment for fall risk prediction in dementia: a systematic review. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2018;45(5–6):353–67.

Eagles D, Yadav K, Perry JJ, Sirois MJ, Emond M. Mobility assessments of geriatric emergency department patients: A systematic review. CJEM. 2018;20(3):353–61.

Ganz DA, Bao Y, Shekelle PG, Rubenstein LZ. Will my patient fall? JAMA. 2007;297(1):77–86.

Lee J, Geller AI, Strasser DC. Analytical review: focus on fall screening assessments. PM R. 2013;5(7):609–21.

Marín-Jiménez N, Cruz-León C, Perez-Bey A, Conde-Caveda J, Grao-Cruces A, Aparicio VA, et al. Predictive Validity of Motor Fitness and Flexibility Tests in Adults and Older Adults: A Systematic Review. J Clin Med. 2022;11(2):328. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11020328.

Omana H, Bezaire K, Brady K, et al. Functional reach test, single-leg stance test, and tinetti performance-oriented mobility assessment for the prediction of falls in older adults: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2021;101(10).

Muir-Hunter SW, Wittwer JE. Dual-task testing to predict falls in community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review. Physiotherapy. 2016;102(1):29–40.

Neuls PD, Clark TL, Van Heuklon NC, et al. Usefulness of the Berg Balance Scale to predict falls in the elderly. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2011;34(1):3–10.

Pamoukdjian F, Paillaud E, Zelek L, et al. Measurement of gait speed in older adults to identify complications associated with frailty: A systematic review. J Geriatr Oncol. 2015;6(6):484–96.

Scott V, Votova K, Scanlan A, Close J. Multifactorial and functional mobility assessment tools for fall risk among older adults in community, home-support, long-term and acute care settings. Age Ageing. 2007;36(2):130–9.

Yang L, Liao LR, Lam FM, He CQ, Pang MY. Psychometric properties of dual-task balance assessments for older adults: a systematic review. Maturitas. 2015;80(4):359–69.

Zijlstra A, Ufkes T, Skelton DA, Lundin-Olsson L, Zijlstra W. Do dual tasks have an added value over single tasks for balance assessment in fall prevention programs? A mini-review. Gerontology. 2008;54(1):40–9.

Chantanachai T, Sturnieks DL, Lord SR, Payne N, Webster L, Taylor ME. Risk factors for falls in older people with cognitive impairment living in the community: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2021;71:101452.

Chen-Ju FW-CC, Meng-Ling L, Niu C-C, Lee Y-H, Cheng C-H. Equipment-free fall-risk assessments for the functionally independent elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Gerontol. 2021;15(4):P301–8.

Kozinc Z, Lofler S, Hofer C, Carraro U, Sarabon N. Diagnostic Balance Tests for Assessing Risk of Falls and Distinguishing Older Adult Fallers and Non-Fallers: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020;10(9).

Menant JC, Schoene D, Sarofim M, Lord SR. Single and dual task tests of gait speed are equivalent in the prediction of falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2014;16:83–104.

Muir SW, Berg K, Chesworth B, Klar N, Speechley M. Quantifying the magnitude of risk for balance impairment on falls in community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(4):389–406.

Rosa MV, Perracini MR, Ricci NA. Usefulness, assessment and normative data of the functional reach test in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2019;81:149–70.

Beauchet O, Annweiler C, Dubost V, et al. Stops walking when talking: a predictor of falls in older adults? Eur J Neurol. 2009;16(7):786–95.

Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed "Up & Go": a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39(2):142–8.

Berg KO, Wood-Dauphinee SL, Williams JI, Maki B. Measuring balance in the elderly: validation of an instrument. Can J Public Health. 1992;83(Suppl 2):S7–11.

Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Pieper CF, et al. Lower extremity function and subsequent disability: consistency across studies, predictive models, and value of gait speed alone compared with the short physical performance battery. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55(4):M221–31.

Lang JT, Kassan TO, Devaney LL, Colon-Semenza C, Joseph MF. Test-Retest Reliability and Minimal Detectable Change for the 10-Meter Walk Test in Older Adults With Parkinson's disease. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2016;39(4):165–70.

Bandinelli S, Pozzi M, Lauretani F, et al. Adding challenge to performance-based tests of walking: The Walking InCHIANTI Toolkit (WIT). Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;85(12):986–91.

Bohannon RW. Single limb stance times: a descriptive meta-analysis of data from individuals at least 60 years of age. Topics Geriatr Rehab. 2006;22(1):70–7.

Weiner DK, Duncan PW, Chandler J, Studenski SA. Functional reach: a marker of physical frailty. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40(3):203–7.

Tinetti ME. Performance-oriented assessment of mobility problems in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1986;34(2):119–26.

Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 1994;49(2):M85–94.

Panel on Prevention of Falls in Older Persons AGS, British Geriatrics S. Summary of the Updated American Geriatrics Society/British Geriatrics Society clinical practice guideline for prevention of falls in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(1):148–57.

Force USPST, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Interventions to Prevent Falls in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;319(16):1696–704.

Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD007146.

Sherrington C, Fairhall NJ, Wallbank GK, et al. Exercise for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;1:CD012424.

(NICE) NIfHaCE. 2019 surveillance of falls in older people: assessing risk and prevention (2013) NICE guideline CG161. Appendix A: Summary of evidence from surveillance. 2019.

Lauretani F, Ticinesi A, Gionti L, et al. Short-Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) score is associated with falls in older outpatients. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2019;31(10):1435–42.

Pettersson B, Nordin E, Ramnemark A, Lundin-Olsson L. Neither Timed Up and Go test nor Short Physical Performance Battery predict future falls among independent adults aged >/=75 years living in the community. J Frailty Sarcopenia Falls. 2020;5(2):24–30.

Gade GV, Jorgensen MG, Ryg J, et al. Predicting falls in community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review of prognostic models. BMJ Open. 2021;11(5):e044170.

Acknowledgements

This systematic review has been performed under the umbrella of the international Task Force on Global Guidelines for Falls in Older Adults; more information can be found at: https://worldfallsguidelines.com/. We would like to acknowledge the role of our research librarian, Lorraine Leff for her help in the early stages of this review and Dr. Adrian Byrne for his instrumental statistical insights.

Funding

The work of Manuel Montero-Odasso and Nellie Kamkar is supported by the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR; MOP 211220; PTJ 153100). The work of Giulia Ogliari and the open access fee was supported by Nottingham Hospitals Charity, Nottingham, UK (grant APP2380/N7359 (N7359 Osteoporosis & Falls Research for “Improving Quality of Life In Older Patients”) and grant FR-000000581/ N1003. All other members’ work is supported as part of the academic funding stream of their respective institutions. The funding sponsors played no part in the design, analysis, and writing of the review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DBJ and KR contributed equally to designing the umbrella review, screening, and reviewing records, extracting data from studies, and writing the manuscript. GO contributed to designing the umbrella review, screening, and reviewing records, and revising the manuscript. NK contributed to running the search and revising the manuscript. MMO, JR, EF, and TM contributed to designing the umbrella review and revising the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: the given and family names of the last author were incorrectly structured: ‘Masud Tahir’ should read ‘Tahir Masud’.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Search strategy in Medline database.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Beck Jepsen, D., Robinson, K., Ogliari, G. et al. Predicting falls in older adults: an umbrella review of instruments assessing gait, balance, and functional mobility. BMC Geriatr 22, 615 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03271-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03271-5