Abstract

Background

Among many screening tools that have been developed to detect frailty in older adults, Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) is a valid, reliable and easy-to-use tool that has been translated in several languages. The aim of this study was to develop a valid and reliable version of the CFS to the Greek language.

Methods

A Greek version was obtained by translation (English to Greek) and back translation (Greek to English). The “known-group” construct validity of the CFS was determined by using test for trends. Criterion concurrent validity was assessed by evaluating the extent that CFS relates to Barthel Index, using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Both inter-rater and test–retest reliability were assessed using intraclass correlation coefficient.

Results

Known groups comparison supports the construct validity of the CFS. The strong negative correlation between CFS and Barthel Index (rs = − 0,725, p ≤ 0.001), supports the criterion concurrent validity of the instrument. The intraclass correlation was good for both inter-rater (0.87, 95%CI: 0.82–0.90) and test-retest reliability (0.89: 95%CI: 0.85–0.92).

Conclusion

The Greek version of the CFS is a valid and reliable instrument for the identification of frailty in the Greek population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Older adults are a highly heterogeneous group, with differences in their health and functional status. Consequently, people with the same chronological age can have different biological ages [1]. In the last 30 years the term frailty is used more and more [2] to understand and describe the health diversity among them. Frailty is conceptualized as the result of the aging process that leads to cumulative decline in many physiological systems and to increased risk of vulnerability [3]. According to the definition of a consensus group, consisting of delegates from six major international, European, and US societies, frailty is “a medical syndrome with multiple causes and contributors that is characterized by diminished strength, endurance, and reduced physiologic function that increases an individual’s vulnerability for developing increased dependency and/or death” [4].

Among many screening tools that have been developed to detect frailty in older adults [5] Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) is a valid, reliable and easy-to-use tool that allows health-care providers to assign a score based only on a standard clinical interview [6], and can also be reliably used retrospectively [7]. It has been introduced as a seven-point scale, ranging from very fit to severely frail, with a visual chart that accompanied a description for each point of the scale [6]. Later, it was expanded from a 7-point scale to the present 9-point scale [8] and recently was further revised with minor edits to the level descriptions and their corresponding labels [9]. It has been largely used to assess the overall level of fitness or frailty in hospitalized [10,11,12,13,14], institutionalized [15,16,17] and community-dwelling [6, 7] older adults and in elderly patients admitted to intensive care units [18,19,20] or evaluated at emergency departments [21,22,23].

As frailty has been associated with mortality [6, 10, 11], length of hospitalization [24,25,26], degree and time of recovery [12, 27], re-admission [11, 25, 28], and future need for institutionalization [6, 24, 29], there is a need for tools that can be used practically and quickly to detect frailty [30]. In order to avoid misclassification due to differences in culture or how someone perceives the English version individually [31], CFS has been translated in several languages [30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. Trying to promote the adequate use of this scale in Greece we aimed to develop a valid and reliable version of the CFS to the Greek language.

Methods

Sample, tools and data collection

A prospective study was conducted among patients older than 65 years old, consecutively admitted through the emergency department of General and Oncological Hospital of Kifissia “Agioi Anargyroi” from September 2020 to January 2021. On admission, after a comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) that requires the evaluation of physical, cognitive, affective, social, financial, and environmental components [37], patients’ demographic characteristics (age, gender, educational level, marital status), medical history (comorbidities), medication use (number and type of medications) and reason of admission were recorded.

Charlson Co-morbidity Index (CCI), which includes most major medical comorbidities [38], was used, for measuring co-morbidity, while activities of daily living were evaluated using Barthel Index [39]. Cognitive status was assessed by using the Global Deterioration Scale, a 7-point scale ranging from no cognitive decline (stage 1) to very severe cognitive decline -severe dementia (stage 7) that can be broken down into three groups (no cognitive decline, mild cognitive impairment, and severe- very severe cognitive impairment) [40]. Both Barthel Index and Global Deterioration Scale were estimated for the baseline status of the patients, when not affected by acute illness. Information regarding demographic characteristics, medical and medication history and functional status were obtained by asking either the patients or their caregivers, when patients were not able to communicate.

After the initial assessment, CFS was scored for each patient (CFS1). In order to evaluate inter-rater reliability, a second CFS assessment was performed by another examiner who did not know the other’s score (CFS2). CFS was also re-assessed by the initial examiner, to evaluate test-retest reliability, at least 2 weeks later, after interrogation of the entire patients’ record (CFS3). CFS1, CFS2 and CFS3 were scored according to the baseline function of the patient, before the onset of acute illness precipitating hospital admission. Before starting this study, the two examiners underwent training regarding the assessment of frailty by using CFS.

The research protocol was approved by the institutional ethical and scientific committee. An informed written consent was obtained from the patients or from their family members.

Obtaining the Greek version of CFS

After obtaining permission from the original authors, two independent translations of the Clinical Frailty Scale, from English into Greek, were done by a translation agency and by a medical doctor with certified excellent knowledge of the English language. The two versions were compared and a consensus-based choice of an appropriate translation was performed by the authors. Then, the Greek version of CFS was retranslated into English by a professional translator and a doctor whose native language was Greek and lives in England. The two back-translators were blinded to the original questionnaire. The authors compared the two back-translated versions with the original and the differences were resolved by agreement between the authors, aiming to improve the Greek translated version. The Greek version was then further assessed by six medical doctors whose native language is Greek and their comments were used to further modify the scale and obtain the definite Greek version (Fig. 1).

Validity and reliability of the Greek version of CFS

The “known-group” construct validity of the CFS was determined by examining hypothesized relationships between sociodemographic and health-related variables and the level of fitness or frailty according to CFS. Specifically, it was expected that the presence of frailty would be associated with older age, higher CCI, mobility problems, falls in previous months, social withdrawal, swallowing problems and the degree of cognitive impairment.

Criterion concurrent validity was assessed by examining the association between CFS and Barthel Index.

CFS1 and CFS2 scores were used for the evaluation of inter-rater, and CFS1 and CFS3 scores were used for the evaluation of test-retest reliability respectively.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed by using SPSS v22.0. For assessing the distribution of evaluated continuous variables the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used. The continuous variables: age, CCI, and number of medications had non-Gaussian distribution and are expressed as median and interquartile range. Categorical variables are expressed as percentages. Patients who were scored 1–3 at CFS were grouped as non-frail and patients who were scored ≥4 were grouped as frail. Construct validity was evaluated by using known groups comparison to test how well the CFS discriminates between subgroups of the study sample that differed in age, CCI, mobility, balance, sociability, swallowing ability and the degree of cognitive impairment. Test for trends was used for comparisons. When p level was < 0.05 the results were considered statistically significant. Criterion concurrent validity was assessed evaluating the extent that CFS relates to Barthel Index, using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Both inter-rater and test–retest reliability of CFS were assessed by using intraclass correlation coefficient with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

During the study period, 145 older patients were admitted to the medical unit through the emergency department. Two of them (one man and one woman) were reluctant to participate and for one more, who was unable to communicate, his caregiver denied to participate in the study. The median age of patients was 82.00 (IQR: 75.75-87.00). Among the participants 74 were women (52.1%) and 68 men (47.9%). As frail were categorized 87 patients (61.3%). Patients’ characteristics are presented in Table 1.

The more prevalent CFS phenotype was 3-“Managing Well” (32 patients), followed by 7-“Living with Severe Frailty” (21 patients) and 6-“Living with Moderate Frailty” (20 patients). The distribution of patients across different CSF scores is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Known groups comparison showed that CFS discriminated well between subgroups of people who were differed in age, CCI, mobility, balance, sociability, swallowing ability and the degree of cognitive impairment. As hypothesized the oldest old, those with affected mobility, balance and swallowing ability and respondents who were socially withdrawn or had impaired cognitive status, had higher CFS scores. The differences in CFS scores across the subgroups were statistically significant and confirmed expected relationships, supporting the construct validity of the instrument (Table 2 and Fig. 3).

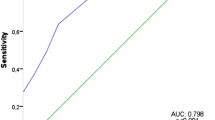

Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was applied to measure the association between CFS and Barthel Index. There was a strong negative correlation among them, which was statistically significant (rs = − 0,725, p ≤ 0.001), supporting the criterion concurrent validity of the instrument. The intraclass correlation was good both for inter-rater reliability, being 0.87 (95%CI: 0.82–0.90) and also for test-retest reliability, being 0.89 (95%CI: 0.85–0.92).

Discussion

The main aim of this study was to translate in the Greek language and validate the revised nine-scale CFS instrument for the evaluation of frailty in elderly patients with a simple and quick way, offering a suitable instrument to the Greek scientific community to identify frailty. In our study, elderly patients were categorized in two groups: frail and non-frail according to the revised version of CFS in which the level description 4 changed from “Vulnerable” to “Living with very mild frailty” [9]. Therefore, patients who were categorized as level 4 were counted as frail. Otherwise, before the revision of the CFS, patients would be classified in three groups [8]: frail (80 patients, 56.4%), vulnerable (7 patients, 4.9%) and non-frail (55 patients, 38.7%).

In this study, we showed that CFS was able to distinguish between groups of elderly patients in the expected manner (known-groups validity) on the basis of age, CCI, mobility, balance, sociability, swallowing ability and the degree of cognitive impairment, providing evidence of its construct validity.

Moreover, the strong negative correlation between CFS and Barthel Index supports the criterion concurrent validity of the instrument. Barthel Index, is an ordinal scale, used to assess performance in activities of daily living [39] and not a direct measure of frailty. Nevertheless, activities of daily living are an essential component of frailty [6, 41, 42] and frailty is related directly with disability in activities of daily living [43]. Therefore, the correlation between CFS and Barthel Index is in line with Taherdoost’s [44] definition, that defines criterion concurrent validity as “the extend that a measure simultaneously relates to another measure that it is supposed to relate”.

Regarding the reliability of CFS, overall, the Greek version exhibited good inter-rater and test-retest reliability.

In Greece only a few studies have been conducted concerning frailty. CFS has only been used twice for research purposes. In the first study, CFS was used evaluating frailty in older patients admitted in an intensive care unit. In this study 25% of the patients were categorized as frail, based on information adapted by the patients’ family or caregiver [45]. In the second one, CFS was used to assess the frailty status of hospitalized elderly patients with atrial fibrillation. Frailty status was found to affect decisions regarding long term anticoagulation therapy [46]. Translation and validation of CFS was not mentioned in both of these studies. The same applies to other studies referring to frailty in patients suffering from multiple myeloma [47] or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [48] and in older Greek women [49, 50], where different tools, rather than CFS, were used. Only recently, Tilburg Frailty Indicator was translated and validated in Greek language in a sample of older patients attending an Urban Health Center [51].

Taking into consideration that in Greece there is a lack of translated and validated frailty screening tools such as CFS, that can be applied in multiple settings [52], it is clear that the Greek version may promote the evaluation of frailty in the Greek population, improving patients’ quality of care and outcomes. More specifically, frailty assessment by using Greek CFS can be applied to guide older patients’ care, taking into consideration the probable risks and benefits, to provide individualized care and to identify those at risk for negative health consequences [52]. Furthermore, the early identification of frailty may guide interventions in order to prevent or reverse disability in older persons [53]. However, at this time, despite some efforts to apply frailty assessment into health-care policy [4, 54, 55] and despite the numerous studies dealing with frailty, the need for the application of all this knowledge into clinical practice still exists [1, 56, 57].

The main study limitation is the lack of a validated Greek translation of another screening tool for the identification of frailty, to compare it with the Greek version of CFS, as a reference method, in order to evaluate its concurrent validity. As mentioned before, the only valid translated tool for frailty assessment, available in Greek language is Tilburg Frailty Indicator [51]. However, this tool includes only self-reported information and it has been developed for the assessment of frailty in the community [58]. So, its use was inappropriate for our study population. Another limitation is that the study sample consisted of hospitalized patients and so, results regarding the prevalence of frailty or other study sample characteristics cannot be generalized in a community-based population.

Conclusion

Τhe results of our study demonstrated that the Greek version of the revised nine-scale CFS is a valid and reliable instrument for the identification of frailty in Greek population.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CFS:

-

Clinical Frailty Scale;

- CCI:

-

Charlson Co-morbidity Index

- GDS:

-

Global Deterioration Scale

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

References

Kojima G, Liljas AEM, Iliffe S. Frailty syndrome: implications and challenges for health care policy. Risk Manag Health Policy. 2019;12:23–30.

Hogan DB, MacKnight C, Bergman H. Steering committee, Canadian initiative on frailty and aging. Models, definitions, and criteria of frailty. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2003;15(3 Suppl):1–29.

Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381(9868):752–62.

Morley JE, Vellas B, van Kan GA, Anker SD, Bauer JM, Bernabei R, et al. Frailty consensus: a call to action. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(6):392–7.

Buta BJ, Walston JD, Godino JG, Park M, Kalyani RR, Xue QL, et al. Frailty assessment instruments: systematic characterization of the uses and contexts of highly-cited instruments. Ageing Res Rev. 2016;26:53–61.

Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, McDowell I, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173(5):489–95.

Davies J, Whitlock J, Gutmanis I, Kane SL. Inter-rater reliability of the retrospectively assigned clinical frailty scale score in a geriatric outreach population. Can Geriatr J. 2018;21(1):1–5.

Pulok MH, Theou O, van der Valk AM, Rockwood K. The role of illness acuity on the association between frailty and mortality in emergency department patients referred to internal medicine. Age Ageing. 2020;49(6):1071–9.

Rockwood K, Theou O. Using the clinical frailty scale in allocating scarce health care resources. Can Geriatr J. 2020;23(3):210–5.

Chong E, Ho E, Baldevarona-Llego J, Chan M, Wu L, Tay L. Frailty and risk of adverse outcomes in hospitalized older adults: a comparison of different frailty measures. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18:638 e7–638 e11.

Chua XY, Toh S, Wei K, Teo N, Tang T, Wee SL. Evaluation of clinical frailty screening in geriatric acute care. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020;26(1):35–41.

Hartley P, Adamson J, Cunningham C, Embleton G, Romero-Ortuno R. Clinical frailty and functional trajectories in hospitalized older adults: a retrospective observational study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17:1063–8.

Hernandez-Luis R, Martin-Ponce E, Monereo-Munoz M, Quintero-Platt G, Odeh-Santana S, Gonzalez-Reimers E, et al. Prognostic value of physical function tests and muscle mass in elderly hospitalized patients. A prospective observational study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2018;18:57–64.

Lewis ET, Dent E, Alkhouri H, Kellett J, Williamson M, Asha S, et al. Which frailty scale for patients admitted via emergency department? A cohort study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2019;80:104–14.

McGibbon CA, Slayter JT, Yetman L, McCollum A, McCloskey R, Gionet SG, et al. An analysis of falls and those who fall in a chronic care facility. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20:171–6.

Matusik P, Tomaszewski K, Chmielowska K, Nowak J, Nowak W, Parnicka A, et al. Severe frailty and cognitive impairment are related to higher mortality in 12-month follow-up of nursing home residents. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;55:22–4.

Rockwood K, Abeysundera MJ, Mitnitski A. How should we grade frailty in nursing home patients? J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2007;8:595–603.

Darvall JN, Greentree K, Braat MS, Story DA, Lim WK. Contributors to frailty in critical illness: multi-dimensional analysis of the clinical frailty scale. J Crit Care. 2019;52:193–9.

Langlais E, Nesseler N, Le Pabic E, Frasca D, Launey Y, Seguin P. Does the clinical frailty score improve the accuracy of the SOFA score in predicting hospital mortality in elderly critically ill patients? A prospective observational study. J Crit Care. 2018;46:67–72.

Muessig JM, Nia AM, Masyuk M, Lauten A, Sacher AL, Brenner T, et al. Clinical frailty scale (CFS) reliably stratifies octogenarians in German ICUs: a multicentre prospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18:162.

Alabaf Sabbaghi S, De Souza D, Sarikonda P, Keevil VL, Wallis SJ, Romero-Ortuno R. Allocating patients to geriatric medicine wards in a tertiary university hospital in England: a service evaluation of the specialist advice for the frail elderly (SAFE) team. Aging Med (Milton). 2018;1:120–4.

Cardona M, Lewis ET, Kristensen MR, Skjot-Arkil H, Ekmann AA, Nygaard HH, et al. Predictive validity of the CriSTAL tool for short-term mortality in older people presenting at emergency departments: a prospective study. Eur Geriatr Med. 2018;9:891–901.

Provencher V, Sirois MJ, Ouellet MC, Camden S, Neveu X, Allain-Boule N, et al. Decline in activities of daily living after a visit to a Canadian emergency department for minor injuries in independent older adults: are frail older adults with cognitive impairment at greater risk? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:860–8.

Basic D, Shanley C. Frailty in an older inpatient population: using the clinical frailty scale to predict patient outcomes. J Aging Health. 2015;27:670–85.

Juma S, Taabazuing M-M, Montero-Odasso M. Clinical frailty scale in an acute medicine unit: a simple tool that predicts length of stay. Can Geriatr J. 2016;19:34–9.

Nolan M, Power D, Long J, Horgan F. Frailty and its association with rehabilitation outcomes in a post-acute older setting. IJTR. 2016;23:33–40.

Sirois MJ, Griffith L, Perry J, Daoust R, Veillette N, Lee J, et al. Measuring frailty can help emergency departments identify independent seniors at risk of functional decline after minor injuries. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72:68–74.

Romero-Ortuno R, Wallis S, Biram R, Keevil V. Clinical frailty adds to acute illness severity in predicting mortality in hospitalized older adults: an observational study. Eur J Intern Med. 2016;35:24–34.

Cheung A, Haas B, Ringer TJ, McFarlan A, Wong CL. Canadian study of health and aging clinical frailty scale: does it predict adverse outcomes among geriatric trauma patients? J Am Coll Surg. 2017;225(5):658–665.e3.

Özsürekci C, Balcı C, Kızılarslanoğlu MC, Çalışkan H, Tuna Doğrul R, Ayçiçek GŞ, et al. An important problem in an aging country: identifying the frailty via 9 point clinical frailty scale. Acta Clin Belg. 2019;28:1–5.

Abraham P, Courvoisier DS, Annweiler C, Lenoir C, Millien T, Dalmaz F, et al. Validation of the clinical frailty score (CFS) in French language. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):322.

Dieperink P, Dijkstra BM, Marten-van Stijn G, Postma-Rowden J, van der Hoeven JG, van den Boogaard M. Validated Dutch translation of the clinical frailty scale for ICU patients and its use in practice. SL J Anaesth Crit Care. 2017;1(1):111.

Ekerstad N, Swahn E, Janzon M, Alfredsson J, Löfmark R, Lindenberger M, et al. Frailty is independently associated with short-term outcomes for elderly patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2011;124(22):2397–404.

Rodrigues MK, Nunes Rodrigues I, Vasconcelos Gomes da Silva DJ, de S Pinto JM, Oliveira MF. Clinical frailty scale: translation and cultural adaptation into the Brazilian Portuguese language. J Frailty Aging. 2021;10(1):38–43.

Ko RE, Moon SM, Kang D, Cho J, Chung CR, Lee Y, et al. Translation and validation of the Korean version of the clinical frailty scale in older patients. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):47.

Nissen SK, Fournaise A, Lauridsen JT, Ryg J, Nickel CH, Gudex C, et al. Cross-sectoral inter-rater reliability of the clinical frailty scale - a Danish translation and validation study. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):443.

Cesari M, Calvani R, Marzetti E. Frailty in older persons. Clin Geriatr Med. 2017;33(3):293–303.

Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–9.

Wade DT, Collin C. The Barthel ADL index: a standard measure of physical disability? Int Disabil Stud. 1988;10(2):64–7.

Reisberg B, Ferris SH, de Leon MJ, Crook T. The global deterioration scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139(9):1136–9.

Mitnitski AB, Mogilner AJ, Rockwood K. Accumulation of deficits as a proxy measure of aging. Sci World J. 2001;1:323–36.

Yang F, Gu D. Predictability of frailty index and its components on mortality in older adults in China. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:145.

Vermeulen J, Neyens JC, van Rossum E, Spreeuwenberg MD, de Witte LP. Predicting ADL disability in community-dwelling elderly people using physical frailty indicators: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2011;11:33.

Taherdoost H. Validity and reliability of the research instrument; how to test the validation of a questionnaire/survey in a research. IJARM. 2016;5:28–36.

Papageorgiou D, Gika E, Kosenai K, Tsironas K, Avramopoulou L, Sela E, et al. Frailty in elderly ICU patients in Greece: a prospective, observational study. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6(7):111.

Papakonstantinou PE, Asimakopoulou NI, Papadakis JA, Leventis D, Panousieris M, Mentzantonakis G, et al. Frailty status affects the decision for long-term anticoagulation therapy in elderly patients with atrial fibrillation. Drugs Aging. 2018;35(10):897–905.

Nikolaou E, Papaioannou P, Kotsanti S, Petsa P, Maltezas D, Tzenou T, et al. Validation of frailty assessment in multiple myeloma (MM) patients. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leucemia. 2017;17(1 Suppl):e137.

Ierodiakonou D, Kampouraki M, Poulonirakis I, Papadokostakis P, Lintovoi E, Karanassos D, et al. Determinants of frailty in primary care patients with COPD: the Greek UNLOCK study. BMC Pulm Med. 2019;19(1):63.

Mamalaki E, Ntanasi E, Anastasiou CA, Lakka S, Kosmidis MH, Hadjigeorgiou GM, et al. Associations between frailty and menopause-related factors: findings from the HELIAD study. Maturitas. 2019;124:147–8.

Mourtzi N, Yannakoulia M, Ntanasi E, Kosmidis MH, Anastasiou CA, Dardiotis E, et al. History of induced abortions and frailty in older Greek women: results from the HELIAD study. Europ Ger Med. 2018;9(3):301–10.

Zhang X, Tan SS, Bilajac L, Alhambra-Borrás T, Garcés-Ferrer J, Verma A, et al. Reliability and validity of the Tilburg frailty indicator in 5 European countries. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(6):772–9.e6.

Church S, Rogers E, Rockwood K, Theou O. A scoping review of the clinical frailty scale. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):393.

Ruiz JG, Dent E, Morley JE, Merchant RA, Beilby J, Beard J, et al. Screening for and managing the person with frailty in primary care: ICFSR consensus guidelines. J Nutr Health Aging. 2020;24(9):920–7.

Rolland Y, Benetos A, Gentric A, Ankri J, Blanchard F, Bonnefoy M, et al. La fragilité de la personne âgée: un consensus bref de la Société française de gériatrie et gérontologie [Frailty in older population: a brief position paper from the French society of geriatrics and gerontology]. Geriatr Psychol Neuropsychiatr Vieil. 2011;9(4):387–90.

Turner G, Clegg A, British Geriatrics Society. Age UK; Royal College of general Practioners best practice guidelines for the management of frailty: a British geriatrics society, age UK and Royal College of general practitioners report. Age Ageing. 2014;43(6):744–7.

Walston J, Robinson TN, Zieman S, McFarland F, Carpenter CR, Althoff KN, et al. Integrating frailty research into the medical specialties-report from a U13 conference. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(10):2134–9.

Huisingh-Scheetz M, Martinchek M, Becker Y, Ferguson MK, Thompson K. Translating frailty research into clinical practice: insights from the successful aging and frailty evaluation clinic. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(6):672–8.

Gobbens RJ, van Assen MA, Luijkx KG, Wijnen-Sponselee MT, Schols JM. The Tilburg frailty Indicator: psychometric properties. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2010;11(5):344–55.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IV conceptualized and designed the study, collected the data, performed statistical analysis, interpreted the results, and wrote the manuscript. PV participated in data collection, helped with the statistical analysis, interpretation of results, and writing the manuscript. SP and AK1 participated in data collection and reviewing the manuscript. AK2 was involved in the development of the overall study conception and design and helped with the interpretation of results and reviewing the manuscript. KM and PS were involved in the development of the overall study conception and design and participated in reviewing-editing the manuscript. DΝ was involved in the development of the overall study conception and study design, participated in the interpretation of results, has the supervision and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from both Institutional Ethical and Scientific Committee of General and Oncology Hospital of Kifissia “Agioi Anargyroi” (approval number: 1494; date of approval: 04/12/2019) and Committee on Bioethics and Deontology of School of Medicine, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (approval number: 284; date of approval: 25/05/2020). The study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their family members, and patients’ anonymity was preserved. Participants or their family members were at any time able to withdraw from the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Vrettos, I., Voukelatou, P., Panayiotou, S. et al. Validation of the revised 9-scale clinical frailty scale (CFS) in Greek language. BMC Geriatr 21, 393 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02318-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02318-3