Abstract

Background

The main objective is to better understand the prevalence of depressive symptoms, in long-term care (LTC) residents with or without cognitive impairment across Western Canada. Secondary objectives are to examine comorbidities and other factors associated with of depressive symptoms, and treatments used in LTC.

Methods

11,445 residents across a random sample of 91 LTC facilities, from 09/2014 to 05/2015, were stratified by owner-operator model (private for-profit, public or voluntary not-for-profit), size (small: < 80 beds, medium: 80–120 beds, large > 120 beds), location (Calgary and Edmonton Health Zones, Alberta; Fraser and Interior Health Regions, British Columbia; Winnipeg Health Region, Manitoba).

Random intercept generalized linear mixed models with depressive symptoms as the dependent variable, cognitive impairment as primary independent variable, and resident, care unit and facility characteristics as covariates were used. Resident variables came from the Resident Assessment Instrument – Minimum Data Set (RAI-MDS) 2.0 records (the RAI-MDS version routinely collected in Western Canadian LTC). Care unit and facility variables came from surveys completed with care unit or facility managers.

Results

Depressive symptoms affects 27.1% of all LTC residents and 23.3% of LTC resident have both, depressive symptoms and cognitive impairment. Hypertension, urinary and fecal incontinence were the most common comorbidities. Cognitive impairment increases the risk for depressive symptoms (adjusted odds ratio 1.65 [95% confidence interval 1.43; 1.90]). Pain, anxiety and pulmonary disorders were also significantly associated with depressive symptoms. Pharmacologic therapies were commonly used in those with depressive symptoms, however there was minimal use of non-pharmacologic management.

Conclusions

Depressive symptoms are common in LTC residents –particularly in those with cognitive impairment. Depressive symptoms are an important target for clinical intervention and further research to reduce the burden of these illnesses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Residents of long term care (LTC) facilities are often frail with multiple comorbidities, poor physical function, cognitive impairment and in many cases concomitant depression [1, 2]. It is estimated in Canada, that up to 44% of those living in LTC have depression [3]. Those living in LTC suffer reduced quality of life [3] and poor function [3] when they have co-morbid depression. Interestingly, the burden of depression is not specific to those who meet solely diagnostic criteria, as those with clinical symptoms also have poor quality of life [3]. Prevalence estimates may be conservative, as evidence suggests that depression is under-diagnosed [3] in LTC.

Depression frequently co-occurs with dementia [4]. In comparison to cognitively intact adults, those with dementia have over two times the risk of developing depression (odds ratio (OR) of 2.64 (95% confidence interval (CI) 2.43; 2.86)) [4]. Existing observational data suggest that depression may be a risk factor for dementia, however depressive symptoms can also be early symptoms of dementia [5]. Residents in LTC commonly experience dementia, given this understanding depression as a comorbidity is important [6]. There are available tools to detect depression in LTC residents [7, 8]; however, use of these tools is limited due to numerous barriers contributing to challenges in detection [9]. There are available therapies for depression in those with and without dementia [10,11,12,13]. There are several risk factors for depression in LTC, the most commonly studied are cognitive impairment, functional disability and baseline depression [14]. However few studies that examine psychological, environmental factors [14].

Depression in LTC residents and in those with dementia is a target for research aimed at understanding this disease in context, to better target resources and improve diagnosis and treatment. A recent systematic review identified several studies examining the prevalence of depression in LTC, however reported no studies within the Canadian context [15]. The reported range of depression was 5–25% for major depression and 14–82% for depressive symptoms in these studies [15]. We were able to identify a Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) report on depression in LTC, however this was focused only on Ontario, Nova Scotia, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and the Yukon [3]. This CIHI report focuses on depressive symptoms as measured by the Depression Rating Scale collected on the interRAI Resident Assessment Instrument Minimum Data Set, Version 2.0 from the Continuing Care Reporting System [3, 16]. They demonstrated that depressive symptoms were present in 44% of participants, with 26% having a depression diagnosis (n = 49,089) [3]. More evidence is needed examining the prevalence of depression in LTC in the western Canadian provinces. It is also unclear in the existing literature how the unit and facility level factors impact depression on the larger scale. It is crucial to understand how depression affects persons living in LTC across Canada in order to inform policy development.

Our primary objectives are to (a) determine the current prevalence of depressive symptoms in LTC residents using cross sectional data across three western provinces, (b) and to understand how this prevalence differs with and without cognitive impairment.. Our secondary objectives were to (a) explore the relationship between depressive symptoms and other prevalent co-morbidities, (b) identify individual and facility factors, and to (c) examine the association of depressive symptoms with available pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic treatments.

Methods

Ethics

Ethics approval was obtained for this study from the appropriate university bodies. Ethics approval was obtained for this study from the University of Calgary (CHREB17–0776) and prior approval for the data collection from University of Alberta (PRO00037937) University of British Columbia (H14–00942), and University of Manitoba (H24014:370(HS17856)).

Study design and setting

This is a cross-sectional analysis of data collected in a representative cohort of 91 urban nursing homes in Western Canada participating in the Translating Research in Elder Care (TREC) program of research [17]. TREC LTC facilities are randomly selected from lists that include all LTC facilities in the participating health regions. Lists are stratified by (a) health region (Calgary and Edmonton Zones in Alberta; Fraser and Interior Health Regions in British Columbia; Winnipeg Region Health Authority in Manitoba), (b) facility size (small, < 80 beds; medium, 80–120 beds; large, > 120 beds), and (c) owner-operator model (private for-profit, public not-for-profit, and voluntary not-for-profit).

Sample

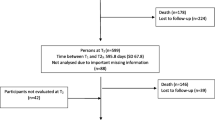

TREC data include Resident Assessment Instrument – Minimum Data Set 2.0 (RAI-MDS 2.0) [18] data from all residents living in participating nursing homes on a quarterly basis since 2007. While newer versions of this tool are available (e.g., the RAI-MDS 3.0 used in US nursing homes [19] or the interRAI LTCF in use in one Canadian province [20]) the RAI-MDS 2.0 is the version mandated and routinely collected in all other Canadian provinces (including the five Western Canadian health regions participating in TREC). From this resident data base, we selected a cross-sectional sample of residents that we linked to survey data from facilities, care units and care staff that TREC collects in waves. Care staff data (not used in this study) and care unit and facility characteristics are collected using validated TREC surveys (details reported elsewhere).(17)We used the latest wave of TREC survey data collection (09/2014–05/2015). Of all resident assessments completed in this period, we included each resident’s latest assessment in this period. Our resident sample includes 11,445 nursing home residents living on 325 care units in 91 nursing homes.

Outcomes and measures

Dependent variable

The dependent variable was depressive symptoms, measured with the Depression Rating Scale (DRS) [21]. The DRS is created by summing the scores of seven items: (a) resident made negative statements (passive suicidal ideation), (b) persistent anger with self or others, (c) expressions of what appear to be unrealistic fears, (d) repetitive health complaints, (e) repetitive anxious complaints or concerns, (f) sad, pained, worried facial expressions, (g) crying, tearfulness. Each item can take on the scores of 0 (not exhibited in last 30 days), 1 (exhibited up to 5 days a week), or 2 (exhibited 6 or 7 days a week), leading to a possible range of the DRS of 0–14. US studies [22, 23] found acceptable specificity rates of the DRS (i.e., rate of residents correctly identified as not having depression > 80%) when compared with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, [24, 25] the Geriatric Depression Scale, [26, 27] chart reviews, or gold standard clinical assessments by a psychiatrist. However, sensitivity of the DRS was low (i.e., rate of residents correctly identified as having depression < 50%) [22, 23]. A recent review found 9 studies validating the DRS, of these studies most included a percentage of patients with dementia (15–70%), only one focused only on those with dementia [28]. A Canadian study found that the DRS at admission predicts a depression diagnosis at follow-up assessments [29]. The cut off for the DRS is ≥3 for detection symptoms of depression, that are more than moderate [3, 21]. Some recent work has shown that even a score of 1–2 can be predictive of patients developing depression. As a result of these latter two factors we dichotomized the DRS and used a cut-off score of ≥2 to indicate presence of depressive symptoms [29]. Further sensitivity analyses are described below.

Primary independent variable

The primary independent variable was cognitive impairment, measured with the RAI-MDS 2.0 Cognitive Performance Scale (CPS) [30]. We preferred the CPS scale over the diagnosis of dementia variables, as dementia is underestimated by at least 11% in the Canadian RAI-MDS 2.0 [31]. Studies have repeatedly confirmed high reliability and validity of the CPS scale [32,33,34]. We created a dichotomous variable reflecting no cognitive impairment (CPS score < 2) or cognitive impairment of any kind (mild to severe) (CPS score ≥ 2). We chose this cut off to represent symptoms of cognitive impairment and this score has been found to be similar to the MMSE in the detection of cognitive impairment in LTC [35]. We adjusted our statistical models for RAI-MDS 2.0 variables listed in Table 1. These covariates were chosen, as they are relevant conditions that are linked to depression in prior studies. We chose to focus on comorbidities in these individuals as they are clearly defined in the databases and rigorously collected.

In addition to covariates (Table 1) included in our statistical models, we assessed use of the following medications in residents with depressive symptoms: antidepressants, antipsychotics, anti-anxiety medication (interRAI data). Looking at only residents with depressive symptoms we assessed the use of antidepressants, antipsychotics, anti-anxiety and pain medications. This was to see what medications those with depressive symptoms were prescribed. However, this has some limitations, as patients who are appropriately treated for depression may not have symptoms and thus not be detected here [36], additionally we cannot account for those started on antidepressants for other indications [37]. Finally, we assessed the following non-pharmacological treatments in residents with depressive symptoms: psychological therapy, special behavior symptom evaluation program, evaluation by a licensed mental health specialist in last 90 days, group therapy, resident-specific deliberate changes in environment, and reorientation.

Unit-level covariates

We included the unit type as measured by our TREC unit survey. Units are categorized as either general long-term care, non-secure dementia, secure dementia, secure mental health/psychiatric, or other. We also added measures for staffing hours per resident day on each unit. We included separate measures for care aide, licensed practical nurse (LPN) and registered nurse (RN) hours per resident day [38].

Facility-level covariates

Facility location (health region), size, and owner-operator model were included as covariates (TREC Survey Data). Three dichotomous variables were added, indicating whether or not care was provided by a geriatrician, a psychiatrist, or a geriatric psychiatrist were available in a facility (interRAI data).

Statistical analyses

We used SAS 9.4® [39] for all analyses. If the included assessment was a quarterly form (and hence certain items that are only include in the full assessment forms were missing), we carried forward the values of these items from the previous full assessment [1]. We calculated means and standard deviations for continuous outcomes and numbers and percentages for dichotomous outcomes for the total sample and by health region. Regional differences for each of the outcomes were assessed, using ANOVA for continuous outcomes that met assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances and Kruskal-Wallis tests for continuous outcomes that violated these assumptions. Fisher’s Exact tests were used tests for categorical outcomes. In residents with depressive symptoms, we assessed differences between residents with and without cognitive impairment in addition to regional differences, using the same statistical methods.

To assess the association of cognitive impairment and of other covariates with depressive symptoms, a three-level random intercept generalized linear mixed models was run [40]. We used a logit link function due to the dichotomous dependent variable (depressive symptoms present or absent) and accounted for dependencies of assessments collected from residents nested within care units and care units nested within facilities by including random unit- and facility-level intercepts. To assess whether the nested model was statistically significantly differed from a non-nested (one-level) model, we performed a covariance test for model independence [41]. These tests indicated that accounting for the clustered structure of the data was necessary (p < 0.0001). We also calculated intra-cluster correlation coefficients for unit- and facility levels (i.e. level-specific variance divided by the total variance). We assessed multicollinearity of model covariates by regressing all model covariates on our depressive symptoms variable, using a multiple linear regression, and specified the collinearity diagnostics (COLL) and variance inflation factor (VIF) options [42]. VIF values ≥10 are commonly considered an indicator that a collinearity problem may be present – although even higher VIF values have been discussed as acceptable [43]. Furthermore, variables with a condition index ≥10 that contribute strongly to the variance of two or more other variables (variance proportion > 0.5) also indicate collinearity problems [44]. Our analyses indicated no multicollinearity problem of our covariates. VIF values ranged between 1.015 (traumatic brain injury) and 4.231 (widowed marital status), and none of the variables explained a variance proportion of > 0.5 of two or more of the other variables. Due to the way RAI-MDS 2.0 data are collected and cleaned in Canada, our data set did not include any missing values. The completeness and integrity of RAI-MDS 2.0 items are extremely high in Canada due to universal use of electronic entry that only allows submission of an assessment when all items are populated with valid values [45]. Furthermore, the Canadian Institute for Health Information, the national agency to which TREC facilities submit RAI-MDS 2.0 data, performs additional data checks on submitted records [45]. Hence, missing items were not an issue in our analyses. We first ran a model with only cognitive impairment included as dependent variable. We then added the other covariates one-by-one in a stepwise approach (see Additional file 1 for parameter estimates of all models). For sensitivity analyses, we ran our final model again (see statistical analyses), and exchanged the dichotomous cognitive impairment variable based on a CPS cut-off ≥2 by another dichotomous variable that indicated cognitive impairment if either (a) the CPS score was ≥2 or (b) the resident had a diagnosis of dementia.

Results

Description of sample characteristics (Table 2)

Among the 11,445 residents, 67.8% (n = 7762) were female with a mean age of 84.7 (SD 10.2). The majority of residents were widowed (49.9%) or married (25.5%). Overall 40.1% had depressive symptoms (n = 4594). Cognitive impairment was the most common comorbidity at 81.6% (n = 9333), which was similar across all locations. The proportion of residents with both depressive symptoms and cognitive impairment was 34.8% (n = 3987). Several comorbidities had a prevalence of over 50%, including hypertension (53.3%), fecal (54.3%) and urinary incontinence (71.9%). Responsive behaviours were also common at 45.5%. Daily pain affected 10.2% of individuals and 15% had fallen in the past 30 days.

Description of LTC facilities (Table 3)

Among the 91 facilities, most facilities were in the Fraser region (n = 27) and fewest in the interior of British Columbia and Calgary (n = 15 each). Majority of facilities were large (> 120 beds; n = 38). Of 91 facilities (n = 42) were private for-profit. All sites had access to geriatric mental health counselling services, but access to geriatricians, geriatric psychiatrists and psychiatrists was variable. Most units were general LTC (68%; n = 220) or secure dementia units (18.2%; n = 59). Care aids, the major provider of direct care, provide a mean of 2.2 h of care per resident per day.

Pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic treatment for those with depressive symptoms (Table 4)

When examining the 3095 residents with depressive symptoms, 86.3% (n = 2671) had cognitive impairment.

Of those who received an antidepressant, 58.2% received antidepressants daily. Of residents with depressive symptoms 7.0% were not on antidepressants. This rate did not differ between residents with and without cognitive impairment. Few residents with depressive symptoms and pain were not receiving analgesics (1.8% in cognitively impaired). Non-pharmacologic strategies were less commonly used. In those with cognitive impairment, behaviour symptom evaluation programs were most commonly used (24.8%), followed by reorientation strategies (19.9%).

Influence of cognitive impairment and other resident, care unit and facility characteristics on depressive symptoms, based on generalized linear mixed models (Table 5)

Our final model (Table 5) indicates that the odds of experiencing depressive symptoms were almost twice as high in people with cognitive impairment than in people without cognitive impairment. Higher age and female sex also increase the odds for depressive symptoms. Of the assessed comorbidities, only anxiety and respiratory disease were independently associated with depressive symptoms (increased odds, as expected). Of the other impairments pain increased the odds for depressive symptoms and ADL impairment decreased the odds of depressive symptoms. Residents living on secure dementia care units had higher odds of depressive symptoms than residents living on general long-term care units. Odds of depressive symptoms on other unit types did not differ from odds on general long-term care units.

The model with unit-level variables included (Additional file 1, Model 6) suggested that an increase of care aide hours per resident day decreased the risk for depressive symptoms. However, this variable was no longer significant when facility variables were added (final model, Table 5). Compared to the Winnipeg Health Region, residents living in a nursing home located in the Calgary and Edmonton Health Zones and in the Interior Health Region have a substantially higher odds of depressive symptoms. The odds of depressive symptoms are also higher for residents living in a public or voluntary not-for profit facility, as compared to a private for-profit facility. Facility size and services provided were not statistically significant predictors of depressive symptoms.

Discussion

Depression in those living in LTC is a complex disease affected by cognitive impairment, multi-morbidity, frailty, and environmental factors. The prevalence of depressive symptoms in LTC is consistently high ranging with a median prevalence of 29% [15]. Our results demonstrate that 27.1% of LTC residents experience depressive symptoms. Nearly 80 % of all LTC residents have cognitive impairment, and of those 23.3% experience depressive symptoms. This estimate furthers our understanding of depression in LTC and what factors may affect these symptoms. This is of critical importance as these other factors may be an important component of developing future intervention studies and management strategies.

Here the DRS is used to measure depressive symptoms. This tool was also used in a 2010 Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) report [3]. This CIHI report found a higher prevalence of depression at 44%, however this examined different regions including Yukon, Saskatchewan, Nova Scotia, Ontario and Manitoba. This report also identifies that cognitive impairment, pain and unstable health conditions are among the common symptoms that effect persons experiencing depressive symptoms’ [3]. Our results identify a lower prevalence of depression, it is possible there is geographic differences in depression. Additionally the analyses presented here are from the 2014–2015 TREC data, where as the CIHI report is from 2008 to 2009 [3]. Interestingly the recent ‘Quick Stats’ CIHI data, which is available online, demonstrates a similar prevalence of depressive symptoms in residential care across to this current analysis multiple provinces 26.2% [16].

Anxiety and pulmonary diseases were independently associated with depressive symptoms. Anxiety is often comorbid with depression in those living in LTC, with 5.1% of cases overlapping (when using strict criteria) [46]. Here, anxiety increased the odds of depression to 2.12 (95%CI 1.72, 2.61). Given anxiety is common in LTC [46] and in those experiencing dementia, [47] this overlap is important from a clinical perspective. Perhaps there should be consideration of screening for both depressive and anxiety symptoms in LTC residents. Of interest, pulmonary diseases were associated with depressive symptoms (1.43; 95% CI 1.25, 1.64). The association of depression and pulmonary disease in LTC was previously noted in other studies [48,49,50]. This association could be attributable to the symptoms, treatment or prognosis of pulmonary disease, thus additional study is needed.

Pain was independently associated with depressive symptoms (OR 2.67; 95% CI 2.28, 3.12). Similarly another study found that those with pain in LTC are 2.83 times more likely to have prevalent depression [51]. This is a key finding, as the management of residents with depressive symptoms related to pain may need a different approach. However, further research is needed to examine the effectiveness of this treatment approach on both mood and pain, and this approach cannot be recommended based on these results alone.

Of those with depressive symptoms and cognitive impairment, 58.8%, with only 7% of people receiving antidepressants without a diagnosis of depression. Here we examine depressive symptoms and not confirmed depression diagnoses, thus it is expected some residents may not be on treatment. Similarly, persons who are on treatment for depression and not exhibiting depressive symptoms would not be represented in this estimate.

Approximately one third of residents with depressive symptoms and cognitive impairment were receiving antipsychotics for 7 days in the past week. Evidence surrounding the use of antipsychotics in the elderly, specifically those with dementia, suggests increased risk of morbidity and mortality therefore it is important to ensure appropriate use of these drugs [52]. However, this data does not identify the reasons for prescription of antipsychotics, thus we are not able to look at those associations based on these data.

The pharmacologic management of depression is only part of the picture. Non-pharmacologic therapies are also recommended and effective [10]. However, there appeared to be little access to these therapies and not all LTC sites had access to specialty mental health resources. In the CIHI study of depression in residential care, mental health services and non-pharmacologic treatment strategies were also rarely employed [3]. There appears to be a care gap related to the underuse non-pharmacological management. Exploring the lack of availability or use of these services may be key to understanding and developing an approach to improve access.

Limitations

This study is unique in that we examine a large population of LTC residents in Western Canada, the prevalence of depressive symptoms and explore the association with co-morbidities, facility and treatment factors. In this study, we can only look at associations and not causation, and cannot assert specific conclusions about the effect of diseases on depression or treatment over time. We used the MDS-RAI 2.0 to estimate the prevalence of symptoms, which is a common practice in this population. Although RAI tool administration is standardized and rigorously applied, we cannot control for specific site or unit differences in training, nor the tool accuracy. The DRS has been criticized for its accuracy [28]. This is when examining the accuracy of diagnosing depression, however here we used the DRS to approximate depressive symptoms in residents.

Conclusions

Depressive symptoms are common in LTC residents. Not surprisingly, cognitive impairment is an independent predictor of depressive symptoms. For those experiencing depressive symptoms, our study has identified several associations with co-morbidities, facility level issues and treatment that warrant in depth study. These represent important targets for future study to both understand and develop better resources to aid in reducing the burden of depression. Understanding that these symptoms are common and the current gaps in related care is key to LTC resource planning.

Availability of data and materials

These data are not available for public access due to the existing ethics approval and policies of TREC.

Abbreviations

- CIHI:

-

Canadian Institute for Health Information

- DRS:

-

Depression Rating Scale.

- LTC:

-

Long Term Care

- OR:

-

Odds Ratio

- RAI-MDS:

-

Resident Assessment Instrument – Minimum Data Set

- TREC:

-

Translating Research in Elder Care

References

Estabrooks CA, Poss JW, Squires JE, Teare GF, Morgan DG, Stewart N, et al. A profile of residents in prairie nursing homes. Canadian Journal on Aging. 2013;32(3):223–31.

Hirdes JP, Mitchell L, Maxwell CJ, White N. Beyond the 'iron lungs of gerontology': using evidence to shape the future of nursing homes in Canada. Canadian Journal on Aging. 2011;30(3):371–90.

Canadian_Institute_for_Health_Information. Depression Among Seniors in Residential Care2010 December 19, 2017. Available from: https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/ccrs_depression_among_seniors_e.pdf.

Snowden MB, Atkins DC, Steinman LE, Bell JF, Bryant LL, Copeland C, et al. Longitudinal Association of Dementia and Depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23(9):897–905.

Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2673–734.

Society A. Rising Tide: The Impact of Dementia on Canadian Society2008. Available from: http://www.alzheimer.ca/sites/default/files/Files/national/Advocacy/ASC_Rising_Tide_Full_Report_e.pdf.

Goodarzi ZS, Mele BS, Roberts DJ, Holroyd-Leduc J. Depression case finding in individuals with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(5):937–48.

Jeon YH, Li Z, Low LF, Chenoweth L, O'Connor D, Beattie E, et al. The clinical utility of the Cornell scale for depression in dementia as a routine assessment in nursing homes. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23(8):784–93.

Colon-Emeric CS, Lekan D, Utley-Smith Q, Ammarell N, Bailey D, Corazzini K, et al. Barriers to and facilitators of clinical practice guideline use in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(9):1404–9.

Goodarzi Z, Mele B, Guo S, Hanson H, Jette N, Patten S, et al. Guidelines for dementia or Parkinson's disease with depression or anxiety: a systematic review. BMC Neurol. 2016;16(1):244.

Orgeta V, Qazi A, Spector A, Orrell M. Psychological treatments for depression and anxiety in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;207(4):293–8.

American Geriatrics S. American Association for Geriatric P. Consensus statement on improving the quality of mental health care in U.S. nursing homes: management of depression and behavioral symptoms associated with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(9):1287–98.

Simning A, Simons KV. Treatment of depression in nursing home residents without significant cognitive impairment: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017;29(2):209–26.

Chau R, Kissane DW, Davison TE. Risk factors for depression in long-term care: a systematic review. Clin Gerontol. 2018:1–14.

Seitz D, Purandare N, Conn D. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among older adults in long-term care homes: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(7):1025–39.

CCRS Continuing Care Reporting System: Profile of Residents in Continuing Care Facilities 2017–2018. [Internet]. CIHI. 2018.

Estabrooks CA, Squires JE, Cummings GG, Teare GF, Norton PG. Study protocol for the translating research in elder care (TREC): building context – an organizational monitoring program in long-term care project (project one). Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):52.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Resident Assessment Instrument (RAI) RAI-MDS 2.0 User's Manual, Canadian Version. Ottawa, ON: CIHI; 2012.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Long-term care facility resident assessment instrument 3.0 User’s manual (version 1.14, 2016). Baltimore, MD: CMS; 2017.

interRAI. Instruments: Long-Term Care Facilities (LTCF) 2016 [Available from: http://www.interrai.org/long-term-care-facilities.html.

Burrows AB, Morris JN, Simon SE, Hirdes JP, Phillips C. Development of a minimum data set-based depression rating scale for use in nursing homes. Age Ageing. 2000;29(2):165–72.

Anderson RL, Buckwalter KC, Buchanan RJ, Maas ML, Imhof SL. Validity and reliability of the minimum data set depression rating scale (MDSDRS) for older adults in nursing homes. Age Ageing. 2003;32(4):435–8.

Watson LC, Zimmerman S, Cohen LW, Dominik R. Practical depression screening in residential care/assisted living: five methods compared with gold standard diagnoses. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(7):556–64.

Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol. 1967;6(4):278–96.

Mulsant BH, Sweet R, Rifai AH, Pasternak RE, McEachran A, Zubenko GS. The use of the Hamilton rating scale for depression in elderly patients with cognitive impairment and physical illness. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1994;2(3):220–9.

Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982;17(1):37–49.

Feher EP, Larrabee GJ, Crook TH 3rd. Factors attenuating the validity of the geriatric depression scale in a dementia population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40(9):906–9.

Penny K, Barron A, Higgins AM, Gee S, Croucher M. Cheung G. Convergent Validity: Concurrent Validity, and Diagnostic Accuracy of the interRAI Depression Rating Scale. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol; 2016.

Martin L, Poss JW, Hirdes JP, Jones RN, Stones MJ, Fries BE. Predictors of a new depression diagnosis among older adults admitted to complex continuing care: implications for the depression rating scale (DRS). Age Ageing. 2008;37(1):51–6.

Morris JN, Fries BE, Mehr DR, Hawes C, Phillips C, Mor V, et al. MDS cognitive performance scale. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1994;49(4):M174–M82.

Bartfay E, Bartfay WJ, Gorey KM. Prevalence and correlates of potentially undetected dementia among residents of institutional care facilities in Ontario, Canada, 2009-2011. International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2013;28(10):1086–94.

Mor V. A comprehensive clinical assessment tool to inform policy and practice: applications of the minimum data set. Med Care. 2004;42(Suppl. 4):50–9.

Poss JW, Jutan NM, Hirdes JP, Fries BE, Morris JN, Teare GF, et al. A review of evidence on the reliability and validity of minimum data set data. Healthc Manage Forum. 2008;21(1):33–9.

Shin JH, Scherer Y. Advantages and disadvantages of using MDS data in nursing research. J Gerontol Nurs. 2009;35(1):7–17.

Paquay L, De Lepeleire J, Schoenmakers B, Ylieff M, Fontaine O, Buntinx F. Comparison of the diagnostic accuracy of the cognitive performance scale (minimum data set) and the mini-mental state exam for the detection of cognitive impairment in nursing home residents. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(4):286–93.

Beck CA, Patten SB. Adjustment to antidepressant utilization rates to account for depression in remission. Compr Psychiatry. 2004;45(4):268–74.

Patten SB, Wang JL, Williams JV, Lavorato DH, Beck CA, Bulloch AG. Frequency of antidepressant use in relation to recent and past major depressive episodes. Can J Psychiatr. 2010;55(8):532–5.

Cummings GG, Doupe M, Ginsburg L, McGregor MJ, Norton PG, Estabrooks CA. Development and validation of a scheduled shifts staffing (ASSiST) measure of unit-level staffing in nursing homes. Gerontologist. 2017;57(3):509–16.

Miu DK, Chan CK. Prognostic value of depressive symptoms on mortality, morbidity and nursing home admission in older people. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2011;11(2):174–9.

Hox JJ. Multilevel Analysis: Techniques and Applications. 2. Auflage ed. New York, Hove: Routledge; 2010. X, 382 S. p.

SAS. SAS/STAT(R) 9.2 User's Guide: COVTEST Statement [Available from: https://support.sas.com/documentation/cdl/en/statug/63033/HTML/default/viewer.htm - statug_glimmix_sect001.htm.

SAS. SAS/STAT(R) 9.2 User's Guide - Collinearity Diagnostics [Available from: https://support.sas.com/documentation/cdl/en/statug/63033/HTML/default/viewer.htm - statug_reg_sect038.htm.

O’Brien RM. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual Quant. 2007;41(5):673–90.

Belsley DA, Kuh E, Welsch RE. Regression diagnostics identifying influential data and sources of collinearity. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2013.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Data quality documentation, continuing care reporting system, 2013–2014. Ottawa, ON: CIHI; 2015.

Smalbrugge M, Jongenelis L, Pot AM, Beekman AT, Eefsting JA. Comorbidity of depression and anxiety in nursing home patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(3):218–26.

Calleo JS, Kunik ME, Reid D, Kraus-Schuman C, Paukert A, Regev T, et al. Characteristics of generalized anxiety disorder in patients with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Dement. 2011;26(6):492–7.

Barca ML, Selbaek G, Laks J, Engedal K. Factors associated with depression in Norwegian nursing homes. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(4):417–25.

Bozek A, Rogala B, Bednarski P. Asthma, COPD and comorbidities in elderly people. J Asthma. 2016;53(9):943–7.

Matte DL, Pizzichini MM, Hoepers AT, Diaz AP, Karloh M, Dias M, et al. Prevalence of depression in COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled studies. Respir Med. 2016;117:154–61.

McCusker J, Cole MG, Voyer P, Monette J, Champoux N, Ciampi A, et al. Observer-rated depression in long-term care: frequency and risk factors. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;58(3):332–8.

Maher AR, Maglione M, Bagley S, Suttorp M, Hu JH, Ewing B, et al. Efficacy and comparative effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic medications for off-label uses in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;306(12):1359–69.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Joseph Akinlawon for aiding us in accessing the data.

Funding

No funding was used to complete this study directly other than the summer student stipend as outlined below.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MH, ZG and JHL were responsible for the study idea, and design. AH, ZG, MH, JKS, JHL planned out the study proposal, and analysis plan (e.g. selecting covariates). MH and AH were responsible for data cleaning, organization and analysis. MH, ZG and JHL were involved in initial interpretation of results. CE obtained the funding for the study from which the data were drawn and is the principle investigator of that study. All study authors were involved in the drafting of the manuscript and final interpretation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was obtained for this study from the University of Calgary (CHREB17–0776) and prior approval for the data collection from University of Alberta (PRO00037937) University of British Columbia (H14–00942), and University of Manitoba (H24014:370(HS17856)).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

ZG has funding for research from the Hotchkiss Brain Institute, the MSI Foundation and the Critical Care Strategic Clinical Network. MH is funded by TREC as a post doctoral trainee. AH had funding from TREC for a summer studentship for the duration of the project. Carole A Estabrooks holds a CIHR Canada Research Chair in Knowledge Translation (Tier 1). JHL an JKS have no disclosures.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hoben, M., Heninger, A., Holroyd-Leduc, J. et al. Depressive symptoms in long term care facilities in Western Canada: a cross sectional study. BMC Geriatr 19, 335 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1298-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1298-5