Abstract

Background

Health care systems are increasingly moving towards more integrated approaches. Shared decision making (SDM) is central to these models but may be complicated by the need to negotiate and communicate decisions between multiple providers, as well as patients and their family carers; particularly for older people with complex needs. The aim of this review was to provide a context relevant understanding of how interventions to facilitate SDM might work for older people with multiple health and care needs, and how they might be applied in integrated care models.

Methods

Iterative, stakeholder driven, realist synthesis following RAMESES publication standards. It involved: 1) scoping literature and stakeholder interviews (n = 13) to develop initial programme theory/ies, 2) systematic searches for evidence to test and develop the theories, and 3) validation of programme theory/ies with stakeholders (n = 11). We searched PubMed, The Cochrane Library, Scopus, Google, Google Scholar, and undertook lateral searches. All types of evidence were included.

Results

We included 88 papers; 29 focused on older people or people with complex needs. We identified four context-mechanism-outcome configurations that together provide an account of what needs to be in place for SDM to work for older people with complex needs. This includes: understanding and assessing patient and carer values and capacity to access and use care, organising systems to support and prioritise SDM, supporting and preparing patients and family carers to engage in SDM and a person-centred culture of which SDM is a part. Programmes likely to be successful in promoting SDM are those that allow older people to feel that they are respected and understood, and that engender confidence to engage in SDM.

Conclusions

To embed SDM in practice requires a radical shift from a biomedical focus to a more person-centred ethos. Service providers will need support to change their professional behaviour and to better organise and deliver services. Face to face interactions, permission and space to discuss options, and continuity of patient-professional relationships are key in supporting older people with complex needs to engage in SDM. Future research needs to focus on inter-professional approaches to SDM and how families and carers are involved.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Shared decision making (SDM) involves patients and health and social care practitioners (HSCPs) jointly offering treatment, care and support packages to reflect, respect and accommodate the patient’s preferences, priorities and goals [1, 2]. Although the original underlying ethos for sharing decisions between patients and HSCPs is based on values, i.e. people have the right to self-determination and autonomy, there is evidence that SDM can lead to better outcomes and care for people [3]. For example, patients who feel involved in the decision and in accord with the HSCP are less likely to need other services such as extra tests or referrals to other HSCPs [4]. More recently SDM has been envisaged as part of person and family centred care and integrated care [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16].

Decision making becomes more complex for older people with multiple health and care needs as the capacity to self-manage is affected by the cumulative effects of long-term conditions. The nature of decisions is complicated by resource availability, polypharmacy, decline in decision making abilities and concordance, availability of support networks, suitability of treatment, safeguarding and the increased likelihood of depression [17,18,19,20]. Moreover, decision making may need to be negotiated between, and communicated to, multiple health and social care practitioners, as well as patients and their families. Whilst there is evidence that many older people and their family carers would like to be involved in decision making [21, 22], there is little evidence relating specifically to SDM with older people with complex health needs.

The skills for sharing and discussing personal information with vulnerable patients, and their families, can be hard to embed in services. There is a need to establish the mechanisms that preserve and foster shared decision making (SDM) between professionals, patients and carers and how they achieve improvements in patient outcomes [23, 24]. Approaches are needed that aim to address the complexity of life when living with, and managing, multiple long-term conditions [25, 26] or recognise the need to consider the abilities of patients and their families to attend to the demands of each condition [19, 27, 28]. Such approaches require the building of relationships, meaningful discussion and SDM between a range of different providers, patients and carers [29].

To develop an understanding of the realities of working in and across complex, overlapping systems of care, it is necessary to synthesise evidence from diverse strands of research [30, 31]. Realist methodology allows the deconstruction of component theories underpinning different interventions and enables us to consider relevant contextual data to test our understanding of the applicability of different approaches for older people with multi-morbidity and how SDM might achieve desired outcomes such as improvements in; patient safety, clinical effectiveness, quality of life and patient experience [23] within the context of integration. The aim of this review was to develop an explanatory account of how interventions to facilitate SDM might work for older people with multiple health and care needs, and how they might be applied to integrated care models.

Methods

Realist synthesis is a systematic, iterative, theory-driven approach designed to make sense of diverse evidence about complex interventions applied in different settings [32,33,34]. The rationale for using a realist synthesis approach for this review is that interventions to promote shared decision making (SDM) in older people with complex health and care needs are likely to be multi-component and are contingent on the behaviours and choices of those delivering or receiving the care.

A realist synthesis assumes a ‘generative’ approach to causation, that is, “to infer a causal outcome (O) between two events (X and Y), one needs to understand the underlying mechanism (M) that connects them and the context (C) in which the relationship occurs. It is typically used to understand complex interventions that ‘often have multiple components (which interact in non-linear ways) and outcomes (some intended and some not) and long pathways to the desired outcome(s)” [32, 35]. Central to the realist review process is the development of programme theory, i.e. what a programme or intervention comprises and how it is expected to work. The review followed the Realist and Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards (RAMESES) publication standards for realist syntheses [36]. A fuller version of the methods is published elsewhere [37].

The synthesis focuses on community dwelling older people with complex health and care needs, for example, people with frailty, multi-morbidity and long-term conditions. The rationale for focusing on this group is that they often use several health and social care services, their needs change over time and/or suddenly, sometimes with progressive loss of cognitive and/or physical function, a family carer is frequently involved in their care, and they are often at risk of exacerbation of their illness and death [17]. In addition, many find it difficult to navigate complicated and under-resourced services and are particularly vulnerable to fragmented care [38]. The focus was generally on those aged 65 years or over, although for certain groups (e.g. people from black and minority ethnic groups (BME), those with mental health problems) we included some younger participants (≥55 years) if the issues were similar. We used an iterative, stakeholder driven approach with three phases.

Phase 1: Development of initial programme theory/ies

In Phase 1 we sought to develop candidate theories about why programmes that seek to promote SDM do, or do not, work. The starting point was systematic reviews of SDM and related topics (such as person-centred care). To identify reviews we searched PubMed and the Cochrane library using the following MESH terms: shared decision making, patient participation, patient decision making, decision support, decision aid, expert patient, proxy decision making, collaborative care, co-construction, coproduction and minimally disruptive medicine. These terms were combined with methodological search terms for systematic reviews. In addition, we undertook key word searches on Google Scholar for both reviews and primary studies and looked for relevant papers published by key authors in the area. We identified 39 systematic reviews and 35 primary studies. In addition, we undertook face to face or telephone interviews with stakeholders in England including user/patient representatives, health care professionals and commissioners/funders, and service providers in integrated care sites. We recruited 13 stakeholders rather than the 20 specified in the protocol. Interviews were conducted using realist principles [39] and participants were a convenience sample recruited for their known expertise in SDM and care of older people. The purpose of the stakeholder consultation was to explore key assumptions about what needs to be in place for effective SDM and identify relevant outcomes. Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Hertfordshire Health and Human Sciences Ethics Committee with delegated authority (ECDA), reference number HSK/SF/UH/02387.

The literature and stakeholder interviews were used to develop preliminary hypotheses in the form of five ‘If-Then’ statements (Table 1). These if-then statements, which helped to specify context and mechanism, were illustrated with supporting evidence from the interviews and literature. ‘If-Then’ statements are the identification of an intervention/activity linked to outcome(s), and contain references to contexts and mechanisms (though these may not be very explicit at this stage), and/or barriers and enablers (which can be both mechanism and context) [40]. The ‘If-Then’ statements helped to focus the process of taking ideas and assumptions about how interventions work and testing them against the evidence we found.

The ‘If-Then’ statements were further developed through discussions at a workshop attended by eight members of the research team and consultation with the Project Advisory Group. The Advisory Group included experts in the field of older people’s health, primary care, patient involvement and realist methods, and experts by experience (Public Involvement representatives).

Phase 2: Retrieval, review and synthesis

In Phase 2 we undertook systematic searches of the evidence to test and develop the theories identified in Phase 1. The focus of the review was on community dwelling older people with complex health and care needs, such as those with frailty, multi-morbidity, dementia. However, we also included other populations where the study was considered to offer opportunities for transferrable learning. Other inclusion criteria were as follows:

-

Older people with complex health needs living in their own homes, in sheltered housing or extra care housing.

-

Any intervention or strategy designed to promote the ongoing engagement of older people with complex health needs, and/or their family carers, in decision making relating to their health or social care needs (e.g. decision aids, physician or patient coaching, education or training, personalised care planning, joint goal setting). The focus was on complex decision making and personal goals rather than single issues (such as whether to have a hip replacement). This included:

-

○ Interprofessional SDM where at least two health care professionals collaborate to achieve SDM with the patient and/or family carer either concurrently or sequentially [41]

-

○ Studies that provide evidence relating to the implementation and uptake of interventions designed to promote SDM for older people with complex health needs.

-

-

Published and unpublished studies of any design.

Data sources included: Medline (PubMed), SCOPUS, The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, DARE (Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects), the HTA Database, NHS EED (NHS Economic Evaluation Database), Google and Google Scholar. The searches were designed to reflect the five ‘If-Then’ statements identified in Phase 1. Date limits and search terms used in PubMed can be seen in Table 2. In addition, we undertook lateral searching such as forward and backward citation tracking. The purpose of the searches was not to identify an exhaustive set of studies but rather to identify sufficient sources for building and testing our programme theory [42]. As is usual with a realist review, the process of identifying relevant information and deciding what to include was iterative involving tracking backwards and forwards between the literature and our review questions [43].

Selection and appraisal of documents

Search results were downloaded into bibliographic software. Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts identified by electronic search and applied the selection criteria to potentially relevant full-text papers. Decisions on inclusion were recorded in an excel spreadsheet. Consistent with a realist review approach, items were assessed for inclusion on the basis of whether they were considered ‘good enough and relevant enough’ [44, 45]. This was an iterative process that involved discussion between team members. Good enough was based on the reviewers’ own assessment of the quality of evidence, for example was it considered to be of a sufficient standard for the type of research, and whether the claims made were considered trustworthy. Relevance related to whether the authors provided sufficient descriptive detail and/or theoretical discussion to contribute to the theories generated in Phase 1. Studies considered by the team to be poorly executed could still be included if the study was considered to contribute to understanding about how a programme was thought to work.

Data extraction and synthesis

A data extraction form was developed, piloted on five records and further refined as necessary. Once the final fields for data extraction were agreed, an electronic version was created in MS Access. The data extraction form included fields relating to study aims, design and methods; the types of participants (e.g. older people, people with long-term health conditions, HSCPs); outcomes; information relevant to the theory areas; and emerging CMOs. Data were extracted by one reviewer with 20% checked by a second reviewer. PDFs in Mendeley were also annotated and relevant sections highlighted. Data in a realist sense are not just restricted to the study results or outcomes measured but also include author explanations and discussions, which can provide a rich source of ‘data’ that makes explicit how an intervention was thought to work or not. The query feature in the ACCESS database was used to create tables to facilitate the identification of prominent recurrent patterns of contexts and outcomes (demi-regularities) in the data and the possible means (mechanisms) by which they occurred [46]. This deliberative and iterative process enabled iteration from plausible explanations to the uncovering of potential context-mechanism-outcome (CMO) configurations.

Phase 3: Testing and refining of programme theory

In Phase 3, we tested the programme theory via interviews with 11 stakeholders and through discussions with the research team and Project Advisory Group. An interview schedule, based on the four CMOs, was used to elicit stakeholders’ views on their meaningfulness, both from practice and service user/carer perspectives. The interview data were used to test the CMOs.

Results

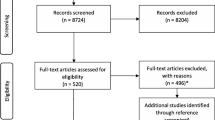

We included 88 items that included 26 evidence reviews, [3, 30, 31, 47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69] 46 primary research studies, [41, 70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116] seven guidelines, cases studies or reports, [8, 14, 117,118,119,120,121] and nine discussion/opinion papers [79, 122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129]. Of the 46 primary research papers, 25 were qualitative studies, five were RCTs and the rest included a variety of study designs. Of the evidence reviews, 20 were systematic reviews, [3, 30, 31, 47,48,49,50, 52,53,54,55,56, 58, 60, 62,63,64,65,66, 69] five were literature reviews, [51, 57, 61, 67, 68] and one was a realist synthesis [59]. The study selection process can be seen in Fig. 1. Thirty-three papers from Phase 1 were excluded at Phase 2 because they were not considered to be of high enough rigour or relevance.

The included literature either focused specifically on SDM or on aspects of care, such as person-centred care or personalised care planning, in which SDM plays an essential if not specified part with the patient or their proxy. We categorised the included reviews and other items according to the focus of the paper. The numbers in each category can be seen in Table 3. Twenty-five primary studies and four systematic reviews focused on older people or those with complex health and care needs. Of those 19 focused on older people or had a population with a mean or median age over 65, nine specified that people had multi-morbidities and 11 that they had long-term conditions.

Sixteen reviews were evaluating an intervention, such as decision aids or tools, coaching, and interventions to increase or promote the adoption of SDM amongst health care professionals. Nineteen of the other papers described or evaluated an intervention. Interventions included care planning, training and education for professionals, the use of decision aids or integrated/collaborative care practices that involved SDM. More details of the reviews can be seen in Additional file 1 and of other items (e.g. primary studies) in Additional file 2.

The theory development, refinement and testing process led to the development of four context-mechanism-outcome (CMO) configurations (see Table 4). Together, these explanations or hypotheses constitute a programme theory about ‘what works’ (or ‘what might work’) to facilitate shared decision-making (SDM) for older people with multiple health and care needs or conditions, and how they might be applied within models of integrated working. Supporting evidence from the stakeholder interviews can be seen in Table 5.

CMO1: Reflecting patient and carer values

Understanding the needs and priorities of service users/patients/carers

Considering patients’ and, where appropriate, family carers’ preferences and values is seen as key to the decision-making process [51, 59, 67, 102, 103, 124]. Systematic review evidence suggests that interventions to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations can have a positive effect on a range of measures although the impacts on satisfaction, behaviour and health status were mixed [56]. Despite this, individual needs and circumstances of patients and their family carers are frequently not taken into account [53, 74, 96, 98]. Reasons for information sharing difficulties, and goal divergence include health care professionals having difficulty identifying patient preferences, [47, 50] differences in the way patients and clinicians interpret and frame the patient’s health problems [94, 110] and clinicians being reluctant to engage in SDM when the patient’s preferences are not in line with clinical guidelines [106] or when there are concerns about safety or cognitive function [98].

Developing relationships

Achieving collaborative approaches to care, such as SDM, depends on building a good relationship in the clinical encounter [59, 74, 83, 90, 97, 101, 103, 104, 109, 115, 128]. This impacts on patient and carer perceptions of the quality of care, [55, 80, 82] and may improve adherence to medical treatments [55]. Increased trust was associated with longer consultations, physician verbal behaviour (such as exploring the impact of the condition or illness on the patient) [130] and continuity of care. [47, 59, 93]. The importance of ongoing relationships and the ability to reassess changing priorities were highlighted in several studies [47, 103]. This was particularly important for people with complex needs or dementia as ‘the dominant chronic illness shifts over time as conditions and treatments change, and re-prioritization occurs’ [51] and decision-making responsibility may shift over time, from the person with dementia to the family carer [91].

Interprofessional working

Partnership working between different health and care professionals was seen as key to decision making for older adults with complex needs [73, 78, 91, 97]. Facilitators of interprofessional working include a history of working together, mutual knowledge and understanding of disciplinary roles, trust and respect, a shared understanding of SDM, and effective communication between individuals (including different health and social care practitioners and patients & carers) [41, 64, 80, 100, 120]. However, few studies addressed an interprofessional approach to SDM, with most studies targeting a single professional group [41, 65].

Patient and carer outcomes

Systematic reviews suggest that interventions to promote SDM may lead to patients and carers feeling more involved in decision making [63, 67]. There is also evidence of improved quality of life and reduced depression in carers, [67] and improved affective cognitive outcomes for patients, such as increased satisfaction and reduced decisional conflict [47]. These impacts (particularly on patient satisfaction) are echoed in many of the other studies we accessed. There is also some evidence that SDM leads to better treatment adherence [118]. There is little evidence, however, to suggest that there is an association between empirical measures of SDM and health outcomes [47].

CMO2: Systems to support SDM

Studies support a link between organisational ‘buy-in’ (e.g. identifying SDM as an organisational priority) and an increase in health and social care practitioner engagement with, and prioritisation of, SDM. However, whilst SDM is a core part of policy in many countries, including the UK, [131] at a service level, systems are not in place to incentivise or appropriately reward patient-centred practice and SDM [96, 128]. Furthermore, for older people with complex conditions SDM is hindered by the risk and uncertainty associated with complex conditions and by systems and structures that block communication between patients and the different professional groups involved in their care [96]. The literature outlines several system based approaches to improve SDM. For example, preparatory work to support the patient’s involvement in decision making, e.g. an initial appointment with a nurse or health care assistant before a meeting with the GP [14], longer appointments, [85, 86] and annual reviews which include monitoring for all chronic conditions [14, 110, 121]. However, little data on patient outcomes are available.

The need for enhanced communication skills among clinicians was a common theme across the papers [30, 47, 53, 56, 59, 87]. This included the ability to address with patients the uncertainty involved in many medical and care decisions [103, 122]. Several studies reported that training to promote person-centred approaches and SDM had positive impacts on SDM skills and engagement [56, 65, 85, 86]; there was less evidence of changes in patient focused outcomes [85, 86, 96]. A UK based study reported that interactive skills training workshops based on a SDM model helped build coherence, improving skills, and promoting positive attitudes. It was also considered important that clinical teams were able to develop a shared understanding of how SDM might differ from their current practice [96].

CMO3: Preparing for the SDM encounter

Decision support

Much of the literature on preparing patients and carers relates to the use of patient decision aids; tools designed to help people participate in decision making about health care options [132]. Systematic reviews provide good evidence that patient decision aids can have a positive impact on patient knowledge, decisional conflict, informed choice, participation in SDM and decision self-efficacy, [3, 48, 49, 54, 62, 69] including for those who are socially disadvantaged [48]. Potential mechanisms relating to the likely benefits of decision aids include patients becoming more engaged, [48] developing greater decisional self-efficacy, [48] feeling more involved in decisions, [85, 86] and increased mutuality [90]. However, the reviews provide little evidence that decision aids improve health outcomes or patient adherence.

Older age, depressive symptoms and difficulties with activities of daily living are associated with decreased patient activation [89]. There is some evidence that decision aids can enhance older adults’ participation in SDM [54, 69]. However, most evidence relates to younger older people (70 years and under) rather than the oldest old (80+) and most tools are not tailored to the needs of people with multi-morbidity [69]. Moreover, there is unlikely to ever be a patient decision aid for every decision, not all patients will find them acceptable or helpful [96], and they may not address the entry level factors to SDM, such as subjective norms and patients’ roles [62, 90]. There is some evidence that the use of coaching or guidance may support patients in the process of thinking about a decision and in communicating their values and preferences with others [68, 70, 92]. The mechanisms inferred from these papers are that improving patients’ deliberation and communication skills will lead to empowerment and thus patients will feel better supported. However, the impact on other outcomes, such as participation in decision making or satisfaction with option chosen, is mixed [68].

Permission/space to discuss option

Key to CMO 3 is that SDM is undertaken in a context where patients and their families can discuss the value and effectiveness of proposed treatments without feeling judged. Longer consultations are linked to greater patient satisfaction and improved SDM, [14, 53, 74, 83, 85, 101, 104, 113] which is likely to be related to the opportunity for patients to ask questions, and feel listened to [83, 101] and respected [97, 109]. However, clinicians’ attitudes may act as a barrier to SDM with older people feeling unable to make their needs heard [76] or reluctant or unable to discuss relevant context or preferences during a consultation [75, 76]. Moreover older people may not always be aware that there is a choice to be made [76]. Research has underscored the importance of family-centred approaches for older people with complex needs [18, 133]. However, similar to a realist review on engaging older adults in healthcare decision making [59], we found few studies that considered the involvement of family members and friends in SDM.

CMO 4: SDM as part of a wider culture change

Time and resources

The programme theory outlined in CMOs 1–3 outlines many barriers to SDM and it is clear that relying on individual clinicians or patients to implement SDM without system-based support is unlikely to be successful or sustainable [60, 62, 65]. Several included papers described system-based changes that involve person-centred, integrated approaches to people with long-term conditions, [8, 14, 82, 121] of which SDM is an integral part. These initiatives reported increased staff and patient satisfaction [8, 14, 121] although the impact on clinical outcomes is not clear. One report suggested that changing patient and professional habits may need a number of care planning cycles [121]. This is reflected in our programme theory which argues that familiarity and a shared expectation of new ways of working (which include SDM) are likely to take time to develop.

Patient activation or engagement

The willingness or ability of patients to participate in SDM is a key contextual factor in our programme theory (see also CMO3). This was supported by the literature, [53] and underscored by our interviews with stakeholders. In general, the consensus from the literature is that although the majority of older people would wish to be involved in decision-making in practice they are often not encouraged, or enabled, to participate in SDM [50, 62, 96]. Reasons for this include limited time, poor continuity of care, environmental conditions, organisational inertia, a biomedical focus, concern about disruption to routines, clinicians’ belief that they are already practicing SDM, and power imbalances [60, 62, 87, 122, 134]. Whilst many SDM initiatives involve giving patients more information, this alone is not enough. Patients need knowledge and power to participate in SDM [62, 135]. A systematic review of patient reported barriers and facilitators to SDM suggested that power may be linked to perceptions of permission to participate in decision making, perceived influence on decision making, confidence in own knowledge and self-efficacy in SDM [62].

Discussion

Summary of the findings

We have developed an explanatory account of what SDM should look like for older people with complex health and care needs (see Fig. 2). Our theory suggests that programmes that are likely to be successful in fostering SDM between older people with complex needs, their family carers and service providers are those that create trust between those involved, that allow older people to feel that they are respected and understood, that are accessible to older people and that engender confidence to engage in SDM. Confidence is likely to take time to develop as, we suggest, it is related to the development of a shared understanding and expectation of SDM between patients and HSCPs. The cultural shift that is needed to embed SDM in practice may require new ways of working for professionals and a shift away from a biomedical focus to a more person-centred ethos that goes beyond the individual patient encounter. To achieve this, health care professionals are likely to need support, both in terms of the way services are organised and delivered and in terms of their own continuing professional development. Older people with complex needs and their family carers may also need support to engage in SDM, which includes interventions that are adapted to their needs (in terms of literacy, health literacy and computer literacy, among other things). How this support might best be provided needs to be further explored, although face to face interactions and ongoing patient-professional relationships are clearly key.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

One of the main limitations of this review is the lack of evidence around interventions to promote SDM in older people with complex health and care needs. The lack of evidence is compounded by little evidence around SDM in integrated care teams. However, in realist methodology, the unit of analysis is the programme theory, or underpinning mechanism of action, rather than the intervention [43]. This meant we were able to draw on a wider literature that provided opportunities for transferable learning, for example studies involving people with long-term conditions or mental health problems. This enabled us to develop a programme theory which can inform initiatives to promote SDM for older people with complex needs. Whilst our searches were systematic the broad nature of our inclusion criteria means that we may have missed potentially relevant literature. However, the nature of realist methodology means that there is not a finite set of relevant papers to be found. Instead the reviewer is able to take a more purposive approach to sampling that aims to identify sufficient sources for theory building and testing rather than identify an exhaustive set of documents [42, 43].

Strengths and weaknesses in relation to other studies

Person-centred approaches to health and care and considering each patient’s preferences and values are central to the SDM process [12]. For older people with complex needs eliciting preferences is likely to involve regularly revisiting decisions because the dominant illness, and priorities, may shift over time [51, 91]. However, the evidence suggests that doctors are better at recognising and discussing options than eliciting patient preferences (see CMO 1). This may reflect the fact that different health and social care practitioners conceptualise person-centred care in different ways [136, 137]. A review of literature on person-centred care suggests that whilst the nursing literature tends to focus more on respecting patients’ values and beliefs in promoting person-centred care, the medical literature has devoted more attention to understanding the nature of the informed decision-making process between the doctor and the patient [136]. What is not explored in the literature is whether integrated care and interprofessional working might enable different members of the multi-disciplinary team to draw on the skills of others in order to promote effective person-centred approaches to SDM.

Meaning of the study

The quality of individual clinicians’ communication skills, and their ability to foster trusting relationships with older people and their families, is fundamental to SDM. SDM education and training should be focused on all members of the multidisciplinary team and not just doctors or lead clinicians. It should be part of undergraduate training programmes but also part of ongoing professional development and should include exploring what matters to patients and how to elicit their goals and priorities. In addition, there is also a need for systems that foster continuity of care. Continuity can be achieved through an ongoing relationship with one clinician (relationship continuity) or a system based approach that develops ways of working whereby the patient is linked to multiple professionals (management and informational continuity) [138,139,140]. The evidence would suggest that both need to be in place. Informational continuity is, however, often hindered by electronic systems not set up to record information relating to patient preferences and goals [110]. The evidence highlights key contextual factors to facilitate SDM for older people, including consultation length, clinicians’ communication skills, and whether it is possible to create a culture that allows people to ask questions without feeling judged. A culture that allows people time to ask questions and to discuss options, and staff with positive attitudes towards SDM are likely to be more important than decision support tools for older people with complex health and care needs. These resources are likely to lead to an increased ability and willingness to engage in SDM through mechanisms such as feeling respected and understood.

Unanswered questions and future research

Evidence from stakeholders and from the literature suggests that older people with complex and competing health and care demands (and where depression is a common comorbidity) may need considerable support to enable them to engage in SDM. This can be exacerbated by factors such as deprivation, low health literacy or cognitive impairment. There is a need for more work to specifically focus on older people with complex needs, for example, more research looking at what is happening in SDM conversations involving older people with complex needs, how patient decision aids are being used and to what effect? More research is needed on family-centred approaches to SDM. For example, what is the impact of making it the default option (with consent from the older person) to involve designated family members in consultations and discussions about treatment options? In addition, whilst models for health care delivery are moving towards a more interprofessional healthcare team-based approach, [24] most evidence concerns decision making involving a single doctor and a patient, and there is a lack of studies addressing interprofessional approaches to SDM [65]. For interprofessional SDM to work the development and involvement of all staff are important [8, 100].

Conclusions

Models of SDM for older people with complex health and care needs should move away from thinking about SDM purely in terms of one doctor/patient encounter. Rather SDM should be conceptualised as a series of conversations that each patient, and their family carers, may have with a variety of different health and care professionals. Such an approach relies on continuity of care fostered through good relationships between practitioners and patients, and systems that facilitate the communication of information, including that about patient goals and preferences, between different health and care professionals. The literature on SDM involving older people or those with complex needs is largely qualitative or descriptive and there are very few evaluations of interventions specifically designed to promote SDM with this group, and with their family carers. This review suggests there is need for further work to establish how organisational structures can be better aligned to the needs of older people with complex needs. This includes a need to define and evaluate the contribution that different members of the health and care team can make to SDM for older people with complex health and care needs.

Abbreviations

- CMO:

-

Context-Mechanism-Outcome

- HSCP:

-

Health and Social Care Practitioner

- PDA:

-

Patient Decision Aid

- SDM:

-

Shared Decision Making

References

Coulter A, Collins A. Making shared decision-making a reality no decision about me, without me. London: The King's Fund; 2011.

Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med 1997/03/01. 1997;44(5):681–92.

Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, Barry MJ, Bennett CL, Eden KB, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; Issue 4, Art No. CD001431.

Elwyn G, Edwards A, Kinnersley P. Shared decision-making in primary care: the neglected second half of the consultation. Br J Gen Pr. 1999;49:477–82.

Elwyn G, Edwards A, Kinnersley P, Grol R. Shared decision-making and the concept of equipoise: the competences of involving patients in healthcare choices. Br J Gen Pr. 2000;50:892–9.

Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making — the pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):780–1.

National Diabetes Support Team. Getting to Grips with the Year of Care: A Practical Guide. 2008;(October):4–5.

Diabetes UK. Department of Health. The Health Foundation. NHS diabetes. Year of care report of findings from the pilot programme. 2011.

Taylor A, Neal D, Jones S, Oliver L, Tipper E, Collins A, et al. Building the House of Care. London; 2015.

Coulter A, Kramer G, Warren T, Salisbury C. Building the house of care for people with long-term conditions: the foundation of the house of care framework. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66(645):e288–90.

Mathers N, Paynton D. Rhetoric and reality in person-centred care: introducing the house of care framework. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66(644):124–5.

NHS Health Educ England, Skills for Care, Skills for Health. Person-Centred Approaches: Empowering people in their lives and communities to enable an upgrade in prevention, wellbeing, health, care and support. 2017.

RCGP. Collaborative Care and Support Planning: Ready to be a reality. 2014.

Glenpark Medical Practice. The Glenpark story implementing care and support planning for people with long term conditions. Gateshead: Year of Care Partnership; 2016.

Hannan R, Thompson R. The Triangle of Care Carers Included: A Guide to Best Practice for Dementia Care. London: Carer’s Trust; 2013.

Year of Care Partnerships. The Year of Care Partnership Programme: Working Together for Better Healthcare and Self Care. Tyneside; 2014.

Banerjee S. Multimorbidity - older adults need health care that can count past one. Lancet Elsevier. 2017;385(9968):587–9.

Bunn F, Burn A-M, Goodman C, Robinson L, Rait G, Norton S, et al. Comorbidity and dementia: a mixed-method study on improving health care for people with dementia (CoDem). Health Serv Deliv Res. 2016;4(8).

Leppin AL, Montori VM, Gionfriddo MR. Minimally Disruptive Medicine: A Pragmatically Comprehensive Model for Delivering Care to Patients with Multiple Chronic Conditions. Healthcare. 2015/01/01. 2015;3(1):50–63.

Gagnon LM, Patten SB. Major depression and its association with long-term medical conditions. Can J Psychiatr. 2002;47(2):149–52.

Chewning B, Bylund CL, Shah B, Arora NK, Gueguen JA, Makoul G. Patient preferences for shared decisions: A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. Elsevier Ireland Ltd; 2012;86(1):9–18. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2011.02.004

Wolff JL, Boyd CM. A Look at person-centered and family-centered care among older adults: results from a National Survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(10):1497–504.

Goodman C, Drennan V, Manthorpe J, Gage H, D. T, Shah D, et al. A study of the effectiveness of inter-professional working for community dwelling older people: Final Report – NIHR Service Delivery and Organisation Programme. 2011.HMSO; 2012.

NHS England. Five year forward view. 2014.

Sinclair AJ, Hillson R, Bayer AJ. National Expert Working G. Diabetes and dementia in older people: a best clinical practice statement by a multidisciplinary National Expert Working Group. Diabet Med. 2014;31(9):1024–31.

Sinclair A, Morley JE, Rodriguez-Manas L, Paolisso G, Bayer T, Zeyfang A, et al. Diabetes mellitus in older people: position statement on behalf of the International Association of Gerontology and Geriatrics (IAGG), the European diabetes working Party for Older People (EDWPOP), and the international task force of experts in diabetes. J Am Med Dir Assoc Elsevier. 2012;13(6):497–502.

Demain S, Goncalves AC, Areia C, Oliveira R, Marcos AJ, Marques A, et al. Living with, managing and minimising treatment burden in long term conditions: a systematic review of qualitative research. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0125457.

May C, Montori VM, Mair FS. We need minimally disruptive medicine. BMJ. 2009;339

Ridgeway JL, Egginton JS, Tiedje K, Linzer M, Boehm D, Poplau S, et al. Factors that lessen the burden of treatment in complex patients with chronic conditions: a qualitative study. Patient prefer adherence. Dove Press. 2014;8:339–51.

Coulter A, Entwistle VA, Eccles A, Ryan S, Shepperd S, Perera R. Personalised care planning for adults with chronic or long-term health conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;3:CD010523.

Sinnott C, Mc Hugh S, Browne J, Bradley CGP. Perspectives on the management of patients with multimorbidity: systematic review and synthesis of qualitative research. BMJ Open. 2013;3(9):e003610.

Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, Buckingham J, Pawson R. RAMESES publication standards: realist syntheses. BMC Med. 2013;11(1):21.

Pawson R. Evidence-based policy: a realist perspective. London: Sage publicaitons; 2006.

Pawson R, Walshe K, Greenhalgh T. Realist synthesis: an introduction. 2004.

Kastner M, Estey E, Perrier L, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Straus SE, et al. Understanding the relationship between the perceived characteristics of clinical practice guidelines and their uptake: protocol for a realist review. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):1–9.

Wong G, Westhorp G, Pawson R, Greenhalgh T. Realist synthesis. RAMESES training materials. RAMESES Proj. 2013:55.

Bunn F, Goodman C, Manthorpe J, Durand M-A, Hodkinson I, Rait G, et al. Supporting shared decision-making for older people with multiple health and social care needs: a protocol for a realist synthesis to inform integrated care models. BMJ Open. 2017;7(2):e014026.

Wong G, Westhorp G, Pawson R, Greenhalgh T. Realist Synthesis. RAMESES Training Materials. NIHR HSDR. 2013:55.

Manzano A. The craft of interviewing in realist evaluation. Evaluation. 2016;22(3):342–60.

Pearson M, Brand SL, Quinn C, Shaw J, Maguire M, Michie S, et al. Using realist review to inform intervention development: methodological illustration and conceptual platform for collaborative care in offender mental health. Implement Sci Implementation Science. 2015;10(1):134.

Legare F, Stacey D, Pouliot S, Gauvin FP, Desroches S, Kryworuchko J, et al. Interprofessionalism and shared decision-making in primary care: a stepwise approach towards a new model. J Interprof Care. 2011;25(1):18–25.

Ford JA, Wong G, Jones AP, Steel N. Access to primary care for socioeconomically disadvantaged older people in rural areas: a realist review. BMJ Open. 2016:1–14.

Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, Walshe K. Realist review--a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J Heal Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(Suppl 1):21–34. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1258/1355819054308530%0A

Rycroft-Malone J, Burton C, Hall B, McCormack B, Nutley S, Seddon D, et al. Improving skills and care standards in the support workforce for older people: a realist review. BMJ Open. 2014;4(5):e005356.

Pawson R. Evidence-based policy: the promise of ‘realist synthesis’. Evaluation. 2002;8(3):340–58.

Wong G, Pawson R, Owen L. Policy guidance on threats to legislative interventions in public health: a realist synthesis. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:222.

Shay AL, Lafata JE. Where is the evidence? A systematic review of shared decision making and patient outcomes. Med Decis Mak. 2015;35(1):114–31.

Durand M-A, Carpenter L, Dolan H, Bravo P, Mann M, Bunn F, et al. Do interventions designed to support shared decision- making reduce health inequalities? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):1–13.

Austin CA, Mohottige D, Sudore RL, Smith AK, Hanson LC. Tools to promote shared decision making in serious illness. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(7):1213.

Belanger E, Rodriguez C, Groleau D. Shared decision-making in palliative care: a systematic mixed studies review using narrative synthesis. Palliat Med. 2011;25(3):242–61.

Bratzke LC, Muehrer RJ, Kehl KA, Lee KS, Ward EC, Kwekkeboom KL. Self-management priority setting and decision-making in adults with multimorbidity: a narrative review of literature. Int J Nurs Stud Elsevier Ltd. 2015;52(3):744–55.

Clayman ML, Bylund CL, Chewning B, Makoul G. The impact of patient participation in health decisions within medical encounters: a systematic review. Med Decis Mak. 2016;36:427–52.

Couët N, Desroches S, Robitaille H, Vaillancourt H, Leblanc A, Turcotte S, et al. Assessments of the extent to which health-care providers involve patients in decision making: a systematic review of studies using the OPTION instrument. Health Expect. 2015;18(4):542–61.

Coylewright M, Branda M, Inselman JW, Shah N, Hess E, LeBlanc A, et al. Impact of sociodemographic patient characteristics on the efficacy of decision aids a patient-level meta-analysis of 7 randomized trials. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7(3):360–7.

Doyle C, Lennox L. Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open. 2013;3(1):1–18.

Dwamena F, Holmes-Rovner M, Gaulden CM, Jorgenson S, Sadigh G, Sikorskii A, et al. Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012/12/14. 2012;12:Cd003267.

Dy SM, Purnell TS. Key concepts relevant to quality of complex and shared decision-making in health care: a literature review. Soc Sci Med Elsevier Ltd. 2012;74(4):582–7.

Edwards M, Davies M, Edwards A. What are the external influences on information exchange and shared decision-making in healthcare consultations: a meta-synthesis of the literature. Patient Educ Couns Ireland. 2009;75(1):37–52.

Elliott J, McNeil H, Ashbourne J, Huson K, Boscart V, Stolee P. Engaging Older Adults in Health Care Decision-Making: A Realist Synthesis. Patient. 2016;9:383–93.

Elwyn G, Scholl I, Tietbohl C, Mann M, Edwards AG, Clay C, et al. “Many miles to go ...”: a systematic review of the implementation of patient decision support interventions into routine clinical practice. BMC Med Inf Decis Mak. 2013;13(Suppl 2):S14.

Fagerlin A, Pignone M, Abhyankar P, Col N, Feldman-Stewart D, Gavaruzzi T, et al. Clarifying values: an updated review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13(Suppl 2):S8.

Joseph-Williams N, Elwyn G, Edwards A. Knowledge is not power for patients: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient-reported barriers and facilitators to shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94(3):291–309.

Land V, Parry R, Seymour J. Communication practices that encourage and constrain shared decision making in health-care encounters: Systematic review of conversation analytic research. Health Expect. 2017;20:1228–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12557.

Legare F, Ratte S, Gravel K, Graham ID. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: update of a systematic review of health professionals’ perceptions. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73(3):526–35.

Légaré F, Stacey D, Turcotte S, Cossi MJ, Kryworuchko J, Graham ID, et al. Interventions for improving the adoption of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;9:CD006732.

Légaré F, Turcotte S, Stacey D, Ratté S, Kryworuchko J, Graham ID. Patients’ perceptions of sharing in decisions. Patient - Patient-Centered Outcomes Res. 2012;5(1):1–19.

Miller LM, Whitlatch CJ, Lyons KS. Shared decision-making in dementia: a review of patient and family carer involvement. Dementia. 2014;15(5):1141–57.

Stacey D, Kryworuchko J, Belkora J, Davison BJ, Durand MA, Eden KB, et al. Coaching and guidance with patient decision aids: a review of theoretical and empirical evidence. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13(Suppl 2):S11.

van Weert JC, van Munster BC, Sanders R, Spijker R, Hooft L, Jansen J. Decision aids to help older people make health decisions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16:45.

Belkora JK, Loth MK, Chen DF, Chen JY, Volz S, Esserman LJ. Monitoring the implementation of consultation planning, recording, and summarizing in a breast care center. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73(3):536–43.

Berntsen GKR, Gammon D, Steinsbekk A, Salamonsen A, Foss N, Ruland C, et al. How do we deal with multiple goals for care within an individual patient trajectory? A document content analysis of health service research papers on goals for care. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e009403.

Blom J, den Elzen W, van Houwelingen AH, Heijmans M, Stijnen T, Van den Hout W, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a proactive, goal-oriented, integrated care model in general practice for older people. A cluster randomised controlled trial: integrated systematic care for older people--the ISCOPE study. Age ageing. England. 2016;45(1):30–41.

Bookey-Bassett S, Markle-Reid M, Mckey CA, Akhtar-Danesh N. Understanding interprofessional collaboration in the context of chronic disease management for older adults living in communities: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs England. 2017;73(1):71–84.

Bridges J, Hughes J, Farrington N, Richardson A. Cancer treatment decision-making processes for older patients with complex needs: a qualitative study. BMJ Open England. 2015;5(12):e009674.

Bugge C, Entwistle VA, Watt IS. The significance for decision-making of information that is not exchanged by patients and health professionals during consultations. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(8):2065–78.

Bynum J, Barre L, Reed Catherine PH. Participation of very old adults in healthcare decisions. Med Decis Mak. 2014;34(2):216–30.

Chong WW, Aslani P, Chen TF. Shared decision-making and interprofessional collaboration in mental healthcare: a qualitative study exploring perceptions of barriers and facilitators. J Interprof Care. 2013;27(5):373–9.

Chong WW, Aslani P, Chen TF. Multiple perspectives on shared decision-making and interprofessional collaboration in mental healthcare. J Interprof Care. 2013;27(3):223–30.

Col N, Bozzuto L, Kirkegaard P, Koelewijnvan Loon M, Majeed H, Jen Ng C, et al. Interprofessional education about shared decision making for patients in primary care settings. J Interprof Care. 2011;25(6):409–15.

Cramm JM, Nieboer AP. The changing nature of chronic care and coproduction of care between primary care professionals and patients with COPD and their informal caregivers. Int J COPD. 2016;11:175–82.

Cramm JM, Nieboer AP. In the Netherlands, rich interaction among professionals conducting disease management led to better chronic care. Health Aff (Millwood). United States. 2012;31(11):2493–500.

Cramm JM, Nieboer AP. A longitudinal study to identify the influence of quality of chronic care delivery on productive interactions between patients and (teams of) healthcare professionals within disease management programmes. BMJ Open. England. 2014;4(9):e005914.

Dardas AZ, Stockburger C, Boone S, An T, Calfee RP. Preferences for shared decision making in older adult patients with orthopedic hand conditions. J Hand Surg Am United States. 2016;41(10):978–87.

Durand M-A, Barr PJ, Walsh T, Elwyn G. Incentivizing shared decision making in the USA – where are we now? Healthc (Amsterdam, Netherlands). Netherlands. 2015;3(2):97–101.

Edwards A, Elwyn G, Hood K, Atwell C, Robling M, Houston H, et al. Patient-based outcome results from a cluster randomized trial of shared decision making skill development and use of risk communication aids in general practice. Fam Pract. 2004;21(4):347–54.

Elwyn G, Edwards A, Hood K, Robling M, Atwell C, Russell I, et al. Achieving involvement: process outcomes from a cluster randomized trial of shared decision-making skill development and use of risk communication aids in general practice. Fam Pr. 2004;21:337–46.

Farrelly S, Lester H, Rose D, Birchwood M, Marshall M, Waheed W, et al. Barriers to shared decision making in mental health care: qualitative study of the joint crisis plan for psychosis. Health Expect. 2016;19(2):448–58.

Fried TR, O’Leary J, Van Ness P, Fraenkel L. Inconsistency over time in the preferences of older persons with advanced illness for life-sustaining treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(7):1007–14.

Gleason KT, Tanner EK, Boyd CM, Saczynski JS, Szanton SL. Factors associated with patient activation in an older adult population with functional difficulties. Patient Educ Couns Elsevier Ireland Ltd. 2016;99(8):1421–6.

Grim K, Rosenberg D, Svedberg P, Schön UK. Shared decision-making in mental health care – A user perspective on decisional needs in community-based services. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2016;11:30563.

Groen-van de Ven L, Smits C, Span M, Jukema J, Coppoolse K, de Lange J, et al. The challenges of shared decision making in dementia care networks [published online ahead of print 9 September 2016]. Int Psychogeriatr; 2016.

Hacking B, Wallace L, Scott S, Kosmala-Anderson J, Belkora J, McNeill A. Testing the feasibility, acceptability and effectiveness of a “decision navigation” intervention for early stage prostate cancer patients in Scotland - a randomised controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2013;22(5):1017–24.

Hart JL, Pflug E, Madden V, Halpern SD. Thinking forward: future-oriented thinking among patients with tobacco-associated thoracic diseases and their surrogates. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(3):321–9.

Herlitz A, Munthe C, Törner M, Forsander G. The counseling, self-care, adherence approach to person-centered care and shared decision making: moral psychology, executive autonomy, and ethics in multi-dimensional care decisions. Health Commun. 2016;31(8):964–73.

Jones JB, Bruce CA, Shah NR, Taylor WF, Stewart WF. Shared decision making: using health information technology to integrate patient choice into primary care. Transl Behav Med United States. 2011;1(1):123–33.

Joseph-Williams N, Lloyd A, Edwards A, Stobbart L, Tomson D, Macphail S, et al. Implementing shared decision making in the NHS: lessons from the MAGIC programme. BMJ. 2017;1744:j1744.

Körner M, Ehrhardt H, Steger A-K. Designing an interprofessional training program for shared decision making. J Interprof Care. 2013;27(2):146–54.

Kuluski K, Gill A, Naganathan G, Upshur R, Jaakkimainen RL, Wodchis WP. A qualitative descriptive study on the alignment of care goals between older persons with multi-morbidities, their family physicians and informal caregivers. BMCFamPract. 2013;14:133.

Ladin K, Lin N, Hahn E, Zhang G, Koch-Weser S, Weiner DE. Engagement in decision-making and patient satisfaction: a qualitative study of older patients’ perceptions of dialysis initiation and modality decisions. Nephrol Dial Transplant England. 2016;32(8):1–8.

Légaré F, Stacey D, Gagnon S, Dunn S, Pluye P, Frosch D, et al. Validating a conceptual model for an inter-professional approach to shared decision making: a mixed methods study. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17(4):554–64.

Mercer SW, O’Brien R, Fitzpatrick B, Higgins M, Guthrie B, Watt G, et al. The development and optimisation of a primary CARE-based whole system complex intervention (CARE plus) for patients with multimorbidity living in areas of high socioeconomic deprivation. Chronic Illn. 2016;12(3):165–81.

Naik AD, Martin LA, Moye J, Health Values KMJ. Treatment goals of older, multimorbid adults facing life-threatening illness. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(3):625–31.

Politi MC, Street RL. The importance of communication in collaborative decision making: facilitating shared mind and the management of uncertainty. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17(4):579–84.

Robben S, van Kempen J, Heinen M, Zuidema S, Olde Rikkert M, Schers H, et al. Preferences for receiving information among frail older adults and their informal caregivers: a qualitative study. Fam Pr. 2012/04/26. 2012;29(6):742–7.

Ruggiano N, Whiteman K, Shtompel N. “If I Don’t like the way I feel with a certain drug, I’ll tell them.”: older adults’ experiences with self-determination and health self-advocacy. J Appl Gerontol 2014/04/23. 2016;35(4):401–20.

Sanders ARJ, Bensing JM, Essed MALU, Magnée T, de Wit NJ, Verhaak PF. Does training general practitioners result in more shared decision making during consultations? Patient Educ Couns. Elsevier Ireland Ltd; 2016;100(3):563–574.

Schaller S, Marinova-Schmidt V, Setzer M, Kondylakis H, Griebel L, Sedlmayr M, et al. Usefulness of a tailored eHealth Service for Informal Caregivers and Professionals in the dementia treatment and care setting: the eHealthMonitor dementia portal. JMIR Res Protoc. 2016;5(2):e47.

Schaller S, Marinova-Schmidt V, Gobin J, Criegee-Rieck M, Griebel L, Engel S, et al. Tailored e-health services for the dementia care setting: a pilot study of “eHealthMonitor”. BMC med inform Decis Mak. England. 2015;15:58.

Shay LA, Lafata JE. Understanding patient perceptions of shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;96(3):295–301.

Sheaff R, Halliday J, Byng R, Øvretveit J, Exworthy M, Peckham S, et al. Bridging the discursive gap between lay and medical discourse in care coordination. Sociol Health Illn. 2017;39:1019–34.

Schuling J, Gebben H, Veehof LJG, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM. Deprescribing medication in very elderly patients with multimorbidity: the view of Dutch GPs. A qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract England. 2012;13:56.

Baqir W, Hughes J, Jones T, Barrett S, Desai N, Copeland R, et al. Impact of medication review, within a shared decision-making framework, on deprescribing in people living in care homes. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2016;24(1):30. LP-33

van JJGT S, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM, Schuling J. Eliciting preferences of multimorbid elderly adults in family practice using an outcome prioritization tool. J Am Geriatr Soc Netherlands. 2016;64(11):e143–8.

Wrede-Sach J, Voigt I, Diederichs-Egidi H, Hummers-Pradier E, Dierks M-L, Junius-Walker U. Decision-making of older patients in context of the doctor-patient relationship: a typology ranging from “self-determined” to “doctor-trusting” patients. Int J Family Med. 2013;2013:478498.

Tietbohl CK, Rendle KAS, Halley MC, May SG, Lin GA, Frosch DL. Implementation of patient decision support interventions in primary care: the role of relational coordination. Med Decis Making United States. 2015;35(8):987–98.

Zoffmann V, Harder I. Kirkevold M. A person-centered communication and reflection model: sharing decision-making in chronic care. Qual Health Res. 2008;18(5):670–85.

Foot C, Gilburt H, Dunn P, Jabbal J, Seale B, Goodrich J, Buck D TJ. People in control of their own health and care: the state of involvement. London; 2014.

Nunes V, Neilson J, O’Flynn N, Calvert N, Kuntze S, Smithson H, et al. Medicines Adherence: involving patients in decisions about prescribed medicines and supporting adherence full guideline January 2009 National Collaborating Centre for primary. London; 2009.

Health Foundation. The Power of People. [cited 14 Jul 2017]. Available from: http://www.health.org.uk/node/10181

Lown BA, Kryworuchko J, Bieber C, Lillie DM, Kelly C, Berger B, et al. Continuing professional development for interprofessional teams supporting patients in healthcare decision making. J Interprof Care. 2011;25(6):401–8.

Holmside Medical Group. The Holmside story person centred primary care: care and support planning. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Quality Care Commission; 2014.

Berger Z. Navigating the unknown: shared decision-making in the face of uncertainty. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(5):675–8.

Agoritsas T, Heen AF, Brandt L, Alonso-Coello P, Kristiansen A, Akl EA, et al. Decision aids that really promote shared decision making: the pace quickens. BMJ. 2015;350:g7624.

Barrett B, Ricco J, Wallace M, Kiefer D, Rakel D. Communicating statin evidence to support shared decision-making. BMC fam Pract. England. 2016;17:41.

Eaton S, Roberts S, Turner B. Delivering person centred care in long term conditions. BMJ. 2015;350(h181):4.

Clayman ML, Gulbrandsen P, Morris MA. A patient in the clinic; a person in the world. Why shared decision making needs to center on the person rather than the medical encounter. Patient Educ Couns. Elsevier Ireland Ltd. 2017;100(3):600–4.

Cooper Z, Koritsanszky LA, Cauley CE, Frydman JL, Bernacki RE, Mosenthal AC, et al. Recommendations for best communication practices to facilitate goal-concordant Care for Seriously ill Older Patients with Emergency Surgical Conditions. Ann Surg. 2016;263(1):1–6.

Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, Joseph-Williams N, Lloyd A, Kinnersley P, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med 2012/05/24. 2012;27(10):1361–7.

Gorin M, Joffe S, Dickert N, Halpern S. Justifying clinical nudges. Hast Cent Rep. 2017;47(2):32–8.

Fiscella K, Meldrum S, Franks P, Shields CG, Duberstein P, McDaniel SH, et al. Patient trust: is it related to patient-centered behavior of primary care physicians? Med Care. 2004;42(11):1049–55.

Depatment of Health. The NHS constitution. Dh; 2015.

IPDAS. International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration: What are patient decision aids. [cited 8 Jul 2017]. Available from: http://ipdas.ohri.ca/what.html

Bunn F, Burn A, Robinson L, Poole M, Rait G, Brayne C, et al. Healthcare organisation and delivery for people with dementia and comorbidity: a qualitative study exploring the views of patients, carers and professionals. BMJ Open. 2017;7(1):e013067.

Joseph-Williams N, Edwards A, Elwyn G. Power imbalance prevents shared decision making. BMJ. 2014;348(3):g3178.

Mavis B, Holmes Rovner M, Jorgenson S, Coffey J, Anand N, Bulica E, et al. Patient participation in clinical encounters: a systematic review to identify self-report measures. Health Expect. 2015;18(6):1827–43.

Kitson A, Marshall A, Bassett K, Zeitz K. What are the core elements of patient-centred care? A narrative review and synthesis of the literature from health policy, medicine and nursing. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(1):4–15.

Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(7):1087–110.

Haggerty JL, Reid RJ, Freeman GK, Starfield BH, Adair CE, McKendry R. Continuity of care: a multidisciplinary review. BMJ. 2003;327(7425):1219–21. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=274066&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract

Freeman GK, Woloshynowych M, Baker R, Boulton M, Guthrie B, Car J, et al. Continuity of care 2006: what have we learned since 2000 and what are policy imperatives now?. National Co-ordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation (NCCSDO). London; 2007 [cited 20 Nov 2017]. Available from: http://www.netscc.ac.uk/hsdr/files/project/SDO_FR_08-1609-138_V01.pdf

Parker G, Corden A, Heaton J. Experiences of and influences on continuity of care for service users and carers: synthesis of evidence from a research programme. Health Soc Care Community. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 19(6):576–601. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2011.01001.x

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contribution of Ms. Sue Davies who worked as a researcher on the project. We thank our Project Advisory Group, Dr. Geoff Wong (Chair), Ms. Jane Hopkins, Mrs. Jeanne Carlin, Ms. Natalie Koussa and patient and public involvement members, Dr. Paul Millac and Ms. Marion Cowe, for their support and guidance.

Study registration: This study is registered as PROSPERO CRD42016039013.

Funding

This work is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) HS&DR project reference: 15/77/25.

This report presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, NETSCC, the HS&DR programme or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Frances Bunn is the guarantor for the manuscript

She affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FB was the principal investigator, led the study, was involved in all aspects of the review process and wrote the manuscript, CG was a coapplicant on the grant, was involved in study design, was involved in research team meetings and workshops, gave feedback between meetings and participated in the synthesis process and preparation of the manuscript, BR was involved in all aspects of the review process and participated in the preparation of the final report, PW was a coapplicant on the grant, was involved in review processes, attended research team meetings and workshops and participated in the preparation of the manuscript, GM was a coapplicant on the grant, was involved in review processes, attended research team meetings and workshops and participated in the preparation of the manuscript, GR was a coapplicant on the grant, was involved in study design, attended workshops and meetings and participated in the preparation of the manuscript, IH was a coapplicant on the grant, was involved in study design, attended workshops and meetings and commented on the final manuscript, MAD was a coapplicant on the grant, was involved in review processes and participated in the preparation of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Hertfordshire Health and Human Sciences Ethics Committee with delegated authority (ECDA), reference number HSK/SF/UH/02387. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

NA

Competing interests

All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at http://www.icmje.org/conflicts-of-interest/ and declare: all authors had financial support from National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) HS&DR for the submitted work, Rait is a member of the HTA Commissioning Board, HTA Methods Group and Panel, Goodman is an NIHR Senior Investigator. Goodman and Manthorpe are Trustees of the Order of St John Care Trust, Manthorpe is Chair of the NIHR Policy Research Programme Board, and Durand reports personal fees from EBSCO Health and ACCESS Community Health Network outside the submitted work. There are no other financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Table summarising details of included systematic reviews. (DOCX 21 kb)

Additional file 2:

Table summarising details of included primary studies. (DOCX 79 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Bunn, F., Goodman, C., Russell, B. et al. Supporting shared decision making for older people with multiple health and social care needs: a realist synthesis. BMC Geriatr 18, 165 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0853-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0853-9