Abstract

Background

Providing high quality acute hospital care for patients with dementia is an increasing challenge as the prevalence of the disease rises. Informal carers of people with dementia are a critical resource for improving inpatient care, due to their insights into patients’ needs and preferences. We summarise informal carers’ perspectives of acute hospital care to inform best practice service delivery.

Methods

We conducted a systematic search of bibliographic databases and sought relevant grey literature. We used thematic synthesis analysis to assimilate results of the studies and describe components of care that influence perceived quality.

Results

Twenty papers met the inclusion criteria. Findings identified four overarching components of care that influenced carer experience and their perceptions of care quality: ‘Patient care’, ‘Staff interactions’, ‘Carer’s situation’ and ‘Hospital environment’. Need for improvement was identified in staff training, provision of help with personal care needs, and dignified treatment of patients. Carers need to be informed, involved and supported during hospital admission in order to promote the most positive experience.

Conclusion

This review identifies common perspectives of informal carers of people with dementia in the acute hospital setting and highlights important areas to address to improve the experience of an admission for both carer and patient.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In the UK, the quality of hospital care for patients with dementia has been widely criticised and attention is focused on achieving improvement [1, 2]. Guidelines, assessment tools and incentives have been developed to promote dementia friendly hospital environments, including the National Dementia Strategy, a Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQIN) reporting framework, inspection by the Care Quality Commission (CQC) and the National Audit of Dementia [3,4,5,6,7].

Globally, the rising number of people living with dementia is creating significant challenges to the provision of appropriate care in the community and hospital [8]. In England, people over 65 years contribute about two thirds of hospital bed days [9]. The estimated population-level prevalence of dementia in this age group is 5% [10, 11]. However, amongst hospital inpatients, the prevalence of dementia is likely to be markedly higher. The UK Royal College of Psychiatrists estimate that a “mental disorder” will be diagnosed in up to 60% of hospital admission in people over 65 [9]. A systematic review found that in high-income settings, the prevalence of dementia in inpatients on medical wards aged over 65 years ranged from 9.1% to 40.0% and in people over 70, the prevalence ranged from 35.2% to 43.2% [12]. There is uncertainty in these estimates due to the marked heterogeneity between settings.

Maintaining independence and managing daily activities becomes challenging for people with dementia as they become increasingly dependent on care provided by other people. A large proportion of this care is provided by informal carers, usually family members (including spouses, children, siblings) [8, 13]. Informal care is defined as the provision of support to sick, elderly or disabled people in a non-professional capacity, usually unremunerated and unchosen [14]. It is widely recognised that caring for a person with dementia can cause significant strain to carers, including psychological distress, poor physical health, social isolation, poor quality of life, financial burden and grief [13, 15,16,17,18,19]. Hospital admissions can also exacerbate carer stress and vulnerability [20].

Informal carers can provide unique insights into the needs and preferences of patients with dementia. By interacting with the healthcare system they can mediate and advocate on behalf of the patient, thereby also supporting the work of healthcare professionals to provide the most appropriate care [3, 21]. The key role that carers can play in improving inpatient care is well recognised [22].

Person-centred care (PCC) is a key concept in the theory of care for people with dementia. This best-practice approach recognises that the wellbeing of the person with dementia is enhanced if carers are able to support their personhood through a social interdependence [23]. To support the application of a PCC model into practice it has been translated into four key elements known as the VIPS framework: (1) Valuing people with dementia and those who care for them; (2) treating people as Individuals; (3) looking at the world from the Perspective of the person with dementia; and (4) a positive Social environment in which the person living with dementia can experience relative wellbeing [24]. The VIPS framework has been adapted for use in nursing homes [25] and in the ‘hospital setting’ the PCC theory is supported by the “Triangle of Care” model that recognises an equal partnership between the person with dementia, healthcare practitioners and informal carers [26].

While the healthcare experience of people with dementia and their carers has been reviewed in primary care settings, there has been no review of the evidence on informal carers’ perspectives on the delivery of acute hospital care for patients with dementia [27]. We therefore conducted a systematic review to assemble and synthesize the published research evidence to describe common perspectives and experiences of informal carers of patients with dementia during acute hospital admission [28]. This information is needed to inform best practice delivery of acute hospital care for patients with dementia.

Methods

Systematic review

The following databases were searched by two reviewers: Medline, Embase, Health Management Information Consortium, and PsycINFO. Using best practice guidelines, search strategies were developed for each database [29] (See Appendix 1 for MEDLINE search strategy). The search was broadened through scanning references and the publication lists of key authors. Grey literature was sought through Google, Google Scholar and ResearchGate, using a combination of free text search terms relating to dementia, acute hospital services, carers, care quality and experiences. The websites of relevant organisations were also searched for publications (See Appendix 2).

Elements of the research question were defined using the SPIDER search tool for qualitative and mixed methods studies [30]. Eligibility criteria were: 1) Sample: informal carers of people who have dementia; 2) Phenomenon of interest: delivery of acute hospital care; 3) Design: studies collecting primary data from carers; 4) Evaluation: experiences and perceptions of care; 5) Research type: qualitative (interviews or focus groups) or quantitative (surveys). Studies with no full text available or non-English language were excluded. There were no exclusions by date. The search and study selection were performed according to the PRISMA statement guidelines and carried out by two researchers (SB and KP).

Relevant findings from the studies were extracted, including data from surveys, quotes from interviews and descriptions or summaries of findings from qualitative research. The quality of evidence provided by each paper was assessed using criteria based on the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) for evaluation of qualitative research; the criteria were adapted to also apply to quantitative and mixed methods studies, as set out in Table 1 [31,32,33]. Papers were graded as high, moderate or low quality based on the total of their ratings for each criterion; grading was carried out by two researchers independently (SB and KP) and their ratings were compared to agree the final allocation. Quality rating did not affect whether publications were included.

Narrative thematic synthesis

A narrative thematic synthesis approach was chosen for the analysis of studies’ results. This method provides an effective way of synthesising qualitative information, which was the predominant methodology of included studies [34]; however, it can also be applied to the quantitative and mixed methods studies by classifying the themes in the results, and therefore allowed the findings of all studies to be compared based on their original context.

The three steps of the thematic synthesis method were used [34]: 1) Coding findings - material was coded line-by-line to identify initial motifs emerging in the data; 2) Developing descriptive themes - initial codes (motifs) were expanded into broader themes by comparison and translation across the studies; 3) Developing analytical themes - key themes and sub-themes were established through further conceptualisation of the material, discussion and analysis. This analysis was carried out by two researchers independently (SB and KP), the findings were combined by SB and the results reviewed by all authors.

Results

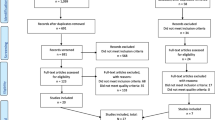

The systematic search and selection process resulted in 20 publications included in the analysis [2, 20, 35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52] (Fig. 1). Study characteristics and quality assessments are shown in Table 2. Two of the included papers originated from Australia, the remaining 18 from the UK. The majority of included papers were research articles (n = 16), followed by doctoral theses (n = 2), public programme reports (n = 1) and charity reports (n = 1). All of the papers reported carer feedback. Sixteen papers used qualitative approaches for data collection (interviewing and observation), three were quantitative analyses of surveys and one used mixed methods. The quality of research was variable, with a mixture of high (n = 8), moderate (n = 6) and low (n = 6) quality papers. In total, this review encompasses the views of 1993 carers, 189 of whom took part in qualitative interviews, 1763 who responded to surveys and 41 who did both.

A large contribution to the research in this area has come from one large randomised controlled trial (RCT) conducted in a single NHS Trust in England. The findings from this work therefore significantly influence the overall synthesis presented in this review. Seven of the papers from this RCT report results from 29 to 40 interviews with carers and 72 h of observation on hospital wards [37, 40, 43, 44, 50,51,52]. One further paper reports the results of a questionnaire study with 462 respondents conducted as part of the trial [45].

We identified four overarching themes within the carers’ perspectives on the delivery of acute hospital care for patients with dementia: ‘Patient care’, ‘Staff interactions’, ‘Carer’s situation’ and ‘Hospital environment’ (Fig. 2).

Patient care

Staff knowledge and skills with dementia

Study findings repeatedly highlighted carers’ concerns that hospital staff did not understand dementia, were untrained and unskilled in managing patients with dementia and could not provide for the needs of this patient group [2, 20, 36, 37, 39,40,41,42,43, 46, 52]. The prevalence of this concern was demonstrated by a survey showing that 67% of carers were dissatisfied with staff who they felt did not recognise cognitive impairment [2]. Staff were perceived not to recognise the specific needs and vulnerabilities of patients with dementia [41, 46] and sometimes to lack patience [40]. This perceived lack of professional knowledge led carers to worry for the safety of the patient, as staff might assume they could recall facts and make decisions [38]. In a study of a specialist medical and mental health unit within an acute hospital, carers gave positive reports of staff being well prepared and displaying positive attitudes towards managing patients with dementia [40].

Medical and nursing care

Some studies highlighted that carers were usually contented with the general care provided in hospital and appreciated the efforts of staff [20, 47,48,49]. However, one survey found that the management of medical problems was one of the most common causes of discontent (22% of carers dissatisfied with this aspect of care), and was an important determinant of overall sentiment [45].

A frequent complaint was the failure of the hospital to provide for basic personal care needs, including help with washing, dressing, toileting, eating, drinking or taking medication [2, 36, 40, 42, 43, 46]. Carers reported appreciation when they witnessed staff proactively helping the patient with these aspects of care [40, 42, 50]. Sensitive provision of personal and intimate care was an important component of perceived good practice, with lack of attention to cleanliness and dignity causing great concern for carers [40].

Omissions in basic care provision were partly attributed to a lack of understanding and compassion on the part of the staff, although low staffing levels were also cited [36]. Carers sympathised with nursing staff being overstretched and acknowledged the strain on the system, despite witnessing inadequacies in care [20, 43, 44, 46]. However, some reported frustration at slow response to call bells or having to ask repeatedly for nurses to attend the patient [46, 50].

Dignity and a person-centred approach

A perceived lack of dignity and respect towards patients with dementia was cited as a concern for carers in several studies [2, 36, 40, 48], including a large survey that found 36% of carers reporting that patients were never treated with dignity and respect [2]. Carers described distress at witnessing hospital staff treating confused patients with a lack of understanding and compassion [36].

Some carers held the view that hospital care was task-focussed and medically oriented, not delivering treatment in a way that took individual needs and preferences into account [20, 40, 41, 44]. In one survey, 68% said hospital care was not person-centred [2]. This was partly attributed to how busy staff on the ward appeared to be, and to competing demands of the system, which were seen to impact negatively on the quality of care delivery and hinder a person-centred approach [20, 41, 42, 52].

Carer feedback highlighted the importance of staff displaying warm, positive attitudes and building caring relationships with patients in order to preserve identity and provide a person-centred experience [50]. Carers recognised and appreciated nurses taking trouble with patients beyond that of providing essential care, as evidenced by staff being positive and welcoming towards patients and demonstrating flexibility and helpfulness in caring for individuals [46].

Staff interactions

Communication and information sharing with carers

Studies consistently highlighted the need for good communication between hospital staff and carers, with poor communication and information provision frequently cited as a grievance [40, 41, 45, 46, 48, 52]. Carers wanted regular communication [35, 40] and frequently needed more information than they received, including details about the patient’s medical condition, disease progression and symptoms, treatment options and care plans [39, 44, 52]. Carers described being left uninformed unless they questioned staff themselves [40] and had to seek information not knowing whom to approach [44, 48]. While one study reported carers actively pushing for information [44], others described them feeling reluctant to interrupt or disturb hospital staff despite wanting to know more [40, 48]. Communication was found to be poor throughout the hospital stay, from admission to discharge [20, 40].

One survey of carers [45] found that 34% were unhappy with how well they were kept informed; in this study it was the greatest cause for dissatisfaction with hospital care as well as being significantly associated with overall rating, demonstrating its strong influence on carers’ views [45]. This finding was confirmed by another study showing that poor communication led carers to express greater dissatisfaction with care quality [40]. Similarly, good communication improved carers’ satisfaction and trust in hospital care [37] and positive feedback highlighted informative staff [40]. Poor communication may act to cause dissatisfaction by leading carers to feel out-of-control and uncertain if adequate care is being provided [44].

Involvement in care and decision-making

Many studies reported that carers felt excluded from the hospital decision-making process and not listened to when they provided information about the patient and their needs [20, 37, 47,48,49]. Lack of involvement led to feelings of powerlessness, dissatisfaction and frustration. In a large survey of over 1000 carers, 43% reported not being involved in decision-making as much as they had wanted [2]. Effective engagement of carers during the hospital admission was found to be necessary to build good relationships and promote contentment with care [52].

Carers wanted to use their knowledge of the patient to influence care and ensure their needs were met [20, 44, 49]. However, staff often failed to seek carer input or to use their expertise in developing care plans, which led to frustration and resentment [20, 46, 48, 49, 52]. Some carers reported finding it difficult to approach medical staff to discuss their concerns or volunteer information [47, 52]. Despite often wanting to be involved in decision-making, some carers did not feel willing or capable to make decisions about medical treatment options and wished to defer final responsibility [52].

There was variation in carers’ feelings towards being directly involved in caring for the patient while in hospital [41, 49, 52]. Some carers wanted to provide hands-on care for the patient as they were used to doing, in order to maintain a sense of normality and to reassure the patient, as well as to express gratitude towards nurses [41, 44, 52]. In these cases, sometimes staff prevented them from doing so [52]. Others did not want to be directly engaged, or felt pressured into doing so to fill gaps in care [38, 40, 41, 52].

Carers’ relationships with hospital staff

Staff attitude towards carers was found to have a strong influence on carer satisfaction with the service and confidence in the quality of care [48]. Studies described “defensive”, “confrontational” and “patronising” attitudes of healthcare professionals, as well as carers feeling deliberately ignored by them [43, 52]. Other studies found that carers felt their concerns were not taken seriously and information they provided about patient needs was often disregarded [20, 37, 38, 48, 49].

Carers who described poor quality relationships were more likely to be discontented with services, particularly when staff failed to engage positively with them, actively disregarded family input or were not perceived to attempt to build connections [37, 40, 51]. Similarly, warm relationships increased satisfaction and trust in the service, with carers feeling reassured when staff recognised the importance of their relationship with the patient and involved them appropriately in care [37, 51].

Carer’s situation

Emotional responses to admission

Carers experienced significant worry about the patient’s wellbeing in hospital. This included distress caused by the acute illness, as well as concern about their mental state and the potential for deterioration during a hospital admission [20, 35, 37, 38, 43, 46, 52]. Due to patients’ communication difficulties, carers worried that they might not be able to make themselves understood if they were frightened, hungry or in pain [37].

Carers described the stressfulness of the admission from their own point of view, feeling vulnerable in the unfamiliar hospital system [20, 35] as well as physically and emotionally exhausted [20, 52]. They described their need for understanding and emotional support from the staff, as well as a particular need for support with information-seeking [20].

Responsibility and advocacy

Carers commonly felt the need to advocate on behalf of patients to ensure their care needs were met in hospital [20, 41, 44, 46, 52]. This led to them spending long periods of time on the ward and continuing to provide physical and emotional care [38, 41]. Feelings of responsibility were due to a number of factors, including having personal insights into the needs of the patient and needing to communicate on their behalf [41]. However, it also included witnessing shortfalls in care and not trusting that proper care would be provided in their absence [41, 46]. Some described feeling obliged to be present and help provide care because staff requested them to [41, 46].

Some carers expressed considerable gratitude for the care received in hospital, and relief at having the responsibility of caring lifted from them [41, 48, 49]. However, one study reported that the inpatient experience was more stressful than daily life due to the hospital requesting them to be present to help manage the patient [38]. This was supported by findings from another study showing that admission did not provide respite for carers, but rather created stress due to extra travelling and disruption to their normal routine [52].

Navigating systems and processes

One of the most prominent areas of frustration for carers was the hospital discharge planning process: one survey found 29% of carers were dissatisfied with this aspect of the hospital experience [45], and another reported around half [47]. Dissatisfaction with discharge was strongly associated with overall rating of care, demonstrating its influence on carer experience [45]. Negative perspectives were described when discharge arrangements were poorly planned and made without consulting the carer [37, 38, 40, 41, 52]. Inappropriate or chaotic discharge planning was a major source of anxiety and frustration, causing carers to feel powerless and distrustful towards the hospital [37, 38, 41]. One study reported that carers felt visiting times were often inflexible and insufficient for their needs [41].

During the hospital stay, carers reported concern about the impact that the admission could have on existing care arrangements in the community, including worries that community support services would be withdrawn due to extended hospital stays [37, 43, 44]. Planning for care of the patient after discharge was another significant strain, with the possibility of long term residential placement becoming necessary causing considerable grief as well as financial concerns [49].

The hospital environment

General ward environment

The general ward environment was perceived by carers to be unsuitable for patients with dementia, not being conducive to the management of distress and confusion and potentially contributing to deteriorating health of the patient: carers noted worsening mental state and behaviour, hospital acquired infections, bedsores and falls [36, 41, 44]. They expected the ward to be a place of safety where patients with behavioural disturbances could be appropriately managed, and expressed concern when they found this was not the case [52]. Incidents of actual or potential harm were reported [46].

Lack of cleanliness was sometimes highlighted by carers, as well as unattractive décor and impersonal surroundings [40]. Others described the ‘bleakness’ of the hospital environment as one of the worst aspects of the hospital stay [48]. Carers in one study found the hospital environment uncomfortable for visiting, lacking sufficient facilities such as chairs and refreshments [37]. Carers were also concerned about frequent ward moves [52], which contributed to stressful losses of personal possessions that sometimes left the impression of an inadequate service [42, 46].

Social environment

Carers reported mixed preferences about the social environment in hospital. Some were concerned about the lack of privacy on shared wards [40, 41], which was reported as one of the worst aspects of the admission by one carer survey [48]. Contrary to this, others described patients’ distress when they were isolated in a separate room [41]. Some carers were unhappy about the disruptive behaviour of other patients on the ward [37, 47, 48] or worried that their own relative would cause disturbance [35, 46].

A large survey found that 62% of carer respondents were dissatisfied with opportunities for social interaction for patients while in hospital [2]. This was corroborated by other studies in which carers reported insufficient or inappropriate provision of activities and opportunities for social engagement [40, 41]. They felt this would leave patients bored or cause behaviours like wandering and shouting [40], however they also recognised that many patients were too unwell to be willing or able to socialise [41]. Carers often took on this role of providing company and stimulation for patients [40, 41].

Interactions between themes

The four themes identified in this review are related and can be seen to interact, reflecting the complexity in how different aspects of healthcare determine carer experience. For example, the standards of patient care witnessed could influence their opinions of staff and of the hospital system. The nature of staff interactions could also affect perceptions of patient care, hospital systems and the ward environment. The carer’s own concerns about the person with dementia were influenced by the care they observed in hospital and the quality of communication with staff, which could in turn affect the way carers interacted with staff and how satisfied they were with the care provided.

Discussion

Principal findings

This review describes the perceptions of informal carers of people with dementia who receive care during an acute hospital admission. We present four themes ‘Patient care’, ‘Staff interactions’, ‘Carer’s situation’ and ‘Hospital environment’ and identify suggestions to inform best practice delivery of services with the aim of improving the experience of both people with dementia and their carers.

This analysis identified the importance of well-trained hospital staff, sufficient nursing care and a dignified, person-centred approach in carers’ estimation of hospital care quality. Good communication, involvement and relationship building between staff and carers is key to supporting a good experience for carers and ensuring that the patient’s individual needs are considered when deciding care plans and providing care. Hospital admission can be a significant source of anxiety for carers both regarding its impact on the patient and the consequences for themselves, for example coping with the emotional effects, potential extra responsibilities and managing practical impacts on community care arrangements. Many carers found the hospital environment to be unsuitable for patients with dementia in both practical and social respects.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

This is the first systematic review of informal carer perspectives on the delivery of acute hospital care for patients with dementia, and provides the only current synthesis of evidence. The search yielded a large number of results and included both scientific and grey literature. While the researchers had access to the principle healthcare databases, other sources were not accessible and therefore certain publications could have been overlooked. All aspects of the search and analysis were conducted independently by two reviewers followed by in-depth discussions of the material to develop shared understanding. The review was not registered with PROPSERO but robust methodology was used [28].

The qualitative data in the primary studies is specific to its own context and therefore may not be transferrable to other settings. In addition, the limited geographical spread of the papers (UK n = 18 and Australia n = 2) makes it unlikely that the findings represent a global perspective, and may have limited transferability even within high-income countries due to the variety of healthcare systems. Eight of the selected papers were published by a single research group and reported results of separate analyses from a single RCT. Due to the high quality and level of detail in these papers, their results will have contributed more evidence to this review than other included studies and therefore may have influenced the findings disproportionately. Synthesis required the secondary analysis of qualitative information that had already undergone interpretation in most cases, and therefore could be subject to the influence of different researchers’ methods and perspectives.

This review presents carer perspectives on acute hospital care delivery as a whole, rather than focussing on aspects that are specific only to dementia care because the feedback presented in the primary studies did not separate dementia-specific features of care. We also described a complex interplay between the extracted themes which suggests that there are many factors important in determining carers’ experiences of care and it is difficult to separate the direct contribution of each.

Finally, this review describes the experience and perspectives of informal carers, and therefore may not represent the viewpoint of patients themselves [53]. In order to comprehensively evaluate service delivery in practice, the perspectives of patients and healthcare professionals should also be gathered, completing the triangle of care.

Relation to similar research

Bridges et al. conducted a systematic review that describes older people’s and relatives’ experiences in acute care settings [54]. This study is not specific to carers’ perspectives or the care of people with dementia but similar themes were identified in this and our study, most notably regarding the importance of relational aspects of care delivery: relationships with staff, a person-centred approach and involvement in decision-making.

The aim of our analysis was to understand the carers’ perspective of the quality of care provided for people with dementia. We sought to identify the key elements of an acute hospital admission that influenced carer views. This differs from the VIPS model of PCC for dementia used in the nursing home setting, which is underpinned by conceptualising personhood through intersubjectivity and social interactions [25]. In the VIPS model, each of the four domains (Value base, Individualised approach, understanding the Perspective, Social psychology) are cross-cutting and focus on the quality and content of social interactions that occur between the person with dementia, healthcare practitioners and carers (as described in the triangle of care model) and recognise the critical role of the carer in providing a valid perspective on the needs and desires of the person with dementia [24,25,26]. Our analysis is grounded by this theoretical framework and is only valid if the relationship between carers and the person with dementia is intact, if the role of the carer participants is to hold together the delivery of PCC and if the carers share useful insights into the perspectives of the person with dementia. We do not replicate the VIPS and PCC models as we focus on structural elements of care; when social interactions or relational aspects of care are included they are situational and specific to one of the four domains of an admission. We consider that our findings could be used by acute healthcare providers to identify elements of current practice that can be targeted for improvement.

Implications of research findings

The findings presented in this review highlight aspects of care that could be practically addressed to improve the delivery of care for people with dementia in acute hospitals. Adequate staff training to support understanding of dementia and appropriate care provision is one area of key importance. Creating dementia friendly environments in hospitals has been the subject of increasing attention and guidelines are available to help care providers achieve improvements [22, 55, 56]. Some key recommendations include using clear signage, lighting, colours, pictures and objects to improve orientation and wayfinding, personal items to promote familiarity, and provision of meaningful activity for example walks and outdoor spaces, books, games and memorabilia [55].

Having systems in place to improve communication and involvement of carers would help in providing individualised patient care as well as supporting carers with their own needs. In recognition of the needs of carers, England introduced The Care Act (2014) in April 2015. This gives local councils and NHS bodies a responsibility for assessing carer’s needs and supporting them [57].

The extent of carer involvement will depend on many factors, including whether the patient has the capacity to make decisions about their medical care, and whether the carer has a lasting power of attorney (LPA) for health and welfare. In all situations when a patient lacks capacity it is best practice for the healthcare team to consult with those close to the patient to better understand the patient’s preferences or values, and the carer’s perspective on the proposed action [58]. In the case of an LPA, carers may have to make decisions on the patient’s behalf regarding treatment options and care plans. This activity and potential responsibility can place considerable demands on an individual.

While carers’ individual situations may not be clearly evident to hospital staff, many are under significant strain and have difficulties managing the caring role and its impact on their health: effective provision of information and signposting to services could help address these issues [59].

Conclusions

This review has identified three aspects of care that influence carer’s perspectives of the quality of a hospital admission for a person with dementia: well-trained hospital staff, sufficient nursing care and a dignified, person-centred approach. Informal carer experience was also more positive when carers were informed, involved and supported during the hospital admission. We suggest that a focus on these factors could improve the perceived quality of a hospital admission by people with dementia and their informal carers.

References

National Audit of Dementia Care in General Hospitals: Second round audit report and update. 2013.

Alzheimer's Society: Counting the cost: caring for people with dementia on hospital wards. 2009.

Department of Health: Living well with dementia: a National Dementia Strategy. 2009.

Department of Health: Prime Minister's challenge on dementia 2015. 2012.

Department of Health: Prime Minister's challenge on dementia 2020. 2015.

NHS England: Commissioning for quality and innovation (CQUIN) guidance 2015/16. 2015.

Royal College of Psychiatrists: National Audit of Dementia. http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/workinpsychiatry/qualityimprovement/nationalclinicalaudits/dementia/nationalauditofdementia.aspx. Accessed Jan 2018.

World Health Organisation: Dementia: a public health priority. 2012.

Who Cares Wins: Improving the outcome for older people admitted to the general hospital: guidelines for the development of liaison mental health services for older people. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2005. https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/pdf/whocareswins.pdf

Alzheimer's Society: Dementia UK Full Report. 2007.

Department of Health: National Service Framework for older people. 2001.

Mukadam N, Sampson EL. A systematic review of the prevalence, associations and outcomes of dementia in older general hospital inpatients. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;23(3):344–55.

Etters L, Goodall D, Harrison BE. Caregiver burden among dementia patient caregivers: a review of the literature. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2008;20:423–8.

The King's Fund: Informal Care in England. 2006.

Office for National Statistics: National census. 2011.

Argimon JM, Limon E, Vila J, Cabezas C. Health-related quality of life in carers of patients with dementia. Fam Pract. 2004;21(4):454–7.

Viana M, Gruber M, Shahly V, Alhamzawi A, Alonso J, Andrade L, Angermeyer M, Benjet C, Bruffaerts R, Caldas-de-Almeida J, et al. Family burden related to mental and physical disorders in the world: results from the WHO world mental health (WMH) surveys. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2013;35(2):115–25.

Wong DFK, Lam AYK, Chan SK, Chan SF. Quality of life of caregivers with relatives suffering from mental illness in Hong Kong: roles of caregiver characteristics, caregiving burdens, and satisfaction with psychiatric services. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:15.

Schulz R, Beach S. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the caregiver health effects study. JAMA. 1999;282(23):2215–9.

Douglas-Dunbar M, Gardiner P. Support for carers of people with dementia during hospital admission. Nurs Older People. 2007;19(8):27–30.

National Audit Office: Improving services and support for people with dementia. 2007.

The NHS Confederation: acute awareness: improving hospital care for people with dementia. 2010.

Kitwood T, Bredin K. Towards a theory of dementia care: personhood and well-being. Ageing Soc. 1992;12:269–87.

Brooker D. What is person-centred care in dementia? Rev Clin Gerontol. 2003;13(3):215–22.

Rosvik J, Kirkevold M, Engedal K, Brooker D, Kirkevold O. A model for using the VIPS framework for person-centred care for persons with dementia in nursing homes: a qualitative evaluative study. Int J Older People Nursing. 2011;6(3):227–36.

Hannan R, Thompson R, Worthington A, Rooney P. The triangle of care - carers included: a guide to best practice for dementia care. London: Carers Trust; 2013.

Prorok JC, Horgan S, Seitz DP. Health care experiences of people with dementia and their caregivers: a meta-ethnographic analysis of qualitative studies. Can Med Assoc J. 2013;185(14):E669–80.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Booth A. Chapter 3: Searching for Studies. In: Noyes J, Booth A, Hannes K, Harden A, Harris J, Lewin S, Lockwood C (editors), Supplementary Guidance for Inclusion of Qualitative Research in Cochrane Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 1 (updated August 2011). Cochrane Collaboration Qualitative Methods Group, 2011. Available from http://cqrmg.cochrane.org/supplemental-handbook-guidance.

Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(10):1435–43.

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Qualitative Research Checklist. 2017. Available at: http://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/dded87_25658615020e427da194a325e7773d42.pdf. Accessed Jan 2018.

Odendaal WA, Goudge J, Griffiths F, Tomlinson M, Leon N, Daniels K. Healthcare workers’ perceptions and experience on using mHealth technologies to deliver primary healthcare services: qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015. Issue 11. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011942.

Shaw RL, Larkin M, Flowers P. Expanding the evidence within evidence-based healthcare: thinking about the context, acceptability and feasibility of interventions. Evid Based Med. 2014;19(6):201–3.

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:45.

Tolson D, Smith M, Knight P. An investigation of the components of best nursing practice in the care of acutely ill hospitalized older patients with coincidental dementia: a multi-method design. J Adv Nurs. 1999;30(5):1127–36.

Dening KH, Greenish W, Jones L, Mandal U, Sampson EL. Barriers to providing end-of-life care for people with dementia: a whole-system qualitative study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2012;2:103–7.

Gladman JRF, Porock D, Griffiths A, Clissett P, Harwood RH, Knight A, Jurgens F, Jones R, Schneider J, Kearney FC: Care of Older People with cognitive impairment in general hospitals. NIHR Service delivery and organisation programme 2012.

Jamieson M, Grealish L, Brown J-A, Draper B. Carers: the navigators of the maze of care for people with dementia - a qualitative study. Dementia. 2014;0(0):1–12.

Thune-Boyle ICV, Sampson EL, Jones L, King M, Lee DR, Blanchard MR. Challenges to improving end of life care of people with advanced dementia in the UK. Dementia. 2010;9(2):259–84.

Spencer K, Foster PER, Whittamore KH, Goldberg SE, Harwood RH. Delivering dementia care differently - evaluating the differences and similarities between a specialist medical and mental health unit and standard acute care wards: a qualitative study of family carers’ perceptions of quality of care. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e004198.

Telford, E. Dementia and physical health care: care accounts of the inpatient experience. ClinPsy Thesis, Cardiff University. 2015. Available at https://orca.cf.ac.uk/76803/1/Elina%20Telford%20Thesis%20Page%20Numbers%20to%20be%20Done1.pdf. Accessed Jan 2018.

Taylor B. Dementia care. How nurses rate. Collegian. 1998;5(4):14–21.

Porock D, Clissett P, Harwood RH, Gladman JRF. Disruption, control and coping: responses of and to the person with dementia in hospital. Ageing Soc. 2015;35(1):37–63.

Clissett P, Porock D, Harwood RH, Gladman JRF. Experiences of family carers of older people with mental health problems in the acute general hospital. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(12):2707–16.

Whittamore KH, Goldberg SE, Bradshaw LE, Harwood RH. Factors associated with family caregiver dissatisfaction with acute Hospital Care of Older Cognitively Impaired Relatives. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:2252–60.

Simpson K. Improving acute care for patients with dementia. Nurs Times. 2016;112(5/6):22–4.

Gonski PN, Moon I. Outcomes of a behavioral unit in an acute aged care service. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;55:60–5.

Simpson RG, Scothern G, Vincent M. Survey of carer satisfaction with the quality of care delivered to in-patients suffering from dementia. J Adv Nurs. 1995;22:517–27.

Cowdell F. The Care of Older People with Dementia in Acute Hospitals (Summary Report). Institute of Health and Community Studies, Bournemouth University, 2007.

Clissett P, Porock D, Harwood RH, Gladman JRF. The challenges of achieving person-centred care in acute hospitals: a qualitative study of people with dementia and their families. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50:1495–503.

Clissett P, Porock D, Harwood RH, Gladman JRF. The responses of healthcare professionals to the admission of people with cognitive impairment to acute hospital settings: an observational and interview study. J Clin Nurs. 2013;23:1820–9.

Jurgens F, Clissett P, Gladman JRF, Harwood RH. Why are family carers of people with dementia dissatisfied with general hospital care? A qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2012;12:57.

Goldberg SE, Harwood RH. Experience of general hospital care in older patients with cognitive impairment: are we measuring the most vulnerable patients’ experience? BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(12):977–80.

Bridges J, Flatley M, Meyer J. Older people's and relatives’ experiences in acute care settings: systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47:89–107.

The King's Fund. Developing Supportive Design for People with Dementia. 2013.

Dementia Action Alliance. Dementia-Friendly Hospital Charter. 2014.

Care Act. 2014. Available at https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2014/23/contents. Accessed Jan 2018.

General Medical Council. Consent: patients and doctors making decisions together. Manchester, UK: General Medical Council; 2008.

HM Government. Recognised, valued and supported: next steps for the carers strategy. 2010.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Chloe Hood and Alan Quirk, Royal College of Psychiatrists, UK, for preliminary discussions about the scope of this review.

Funding

This study was funded by Imperial College Healthcare Charity and the Royal College of Psychiatrists. Helen Ward received funding from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre based at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust and Imperial College London.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SB helped conceive the study and conducted the systematic search, study selection, qualitative synthesis analysis, interpretation and writing. KP carried out the systematic search, study selection and qualitative synthesis analysis, and contributed to the writing. HW and BD led the conception of the study, participated in its design and coordination and helped draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The Patient Experience Research Centre, Imperial College London (HW, BD and SB) was funded by the Royal College of Psychiatrists to develop a carer questionnaire for the National Dementia Audit.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

List of organisations’ websites searched for additional publications

-

1.

Alzheimer’s Society (UK): https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/

-

2.

Alzheimer’s Association (US): http://www.alz.org/care/overview.asp

-

3.

Department of Health (England and Wales): https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/department-of-health

-

4.

Royal College of Nursing (UK): https://www.rcn.org.uk/

-

5.

Age UK: http://www.ageuk.org.uk/

-

6.

Carers UK: http://www.carersuk.org/

-

7.

Alzheimer Europe: http://www.alzheimer-europe.org/

-

8.

Alzheimer’s Disease International: https://www.alz.co.uk/

-

9.

Alzheimer’s Australia: https://www.fightdementia.org.au/

-

10.

World Health Organisation: http://www.who.int/en/

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Beardon, S., Patel, K., Davies, B. et al. Informal carers’ perspectives on the delivery of acute hospital care for patients with dementia: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr 18, 23 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0710-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0710-x