Abstract

Background

Although population-based studies have shown frailty predicted future falls, their follow-up periods were one year or longer and short-term fall risks associated with frailty are unknown.

Methods

A prospective cohort study nested within a randomised controlled trial was conducted to examine associations between frailty and short-term incident future falls among community-dwelling older people. Two hundred forty eight community-dwelling people > =65 years without history of > =three falls and allocated to a usual care arm of exercise intervention trial were prospectively monitored for falls over 24 weeks. Frailty index (FI) was constructed from 40 deficits at baseline. The future fall risks according to frailty status was examined using logistic regression models.

Results

Of 248 participants, 46 were classified as frail and 57 had one or more falls during follow-up. Both each 0.01 increase in FI and frailty defined as FI > =0.25 were significantly associated with higher risks of future falls in multivariate logistic regression models adjusted for age, gender and history of two falls in the previous year (odds ratio (OR) = 1.05, 95 % confidence interval (95 % CI) = 1.02–1.07, p < 0.001; OR = 3.04, 95 % CI = 1.53–6.02, p = 0.001, respectively). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis showed FI predicted future falls with fair accuracy with area under ROC curve of 0.62 (95 % CI = 0.53–0.71, p < 0.01).

Conclusions

Frailty was a significant and independent predictor of short-term future falls among community-dwelling older people who had volunteered for a physical activity study. It is important for healthcare practitioners to recognise frailty as a risk factor of imminent future falling even in older people who appear to be ageing well.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Frailty is a syndrome resulting from age-related cumulative declines across multiple physiological systems characterised by decreased homeostatic reserves and increased vulnerability to adverse health outcomes including disabilities, hospitalisation, institutionalisation, or death [1, 2]. Recent guidelines from the British Geriatric Society advocate assessment of frailty during all encounters with health and social care professionals [2].

Frailty is also recognised as a risk factor for falls [1, 3]. Main features of frailty include weakness, as well as balance and gait problems, all of which predispose older people to falling [1]. Falls in older people often occur as a result of diminished functional reserve capacity involved in maintaining the upright position and vulnerability to internal and external stressors, such as environmental hazards, impairments, disease processes, or adverse pharmacological effects [4]. Approximately 30 % of older people aged 65 years or more and 50 % of those over 80 years fall every year [5]. Not only are falls related to injuries or fractures and are a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in older people, [6] but falls are also shown to have a negative psychological impact. The negative consequences related to falls include fear of falling, loss of confidence, anxiety, depressive symptoms and decreased self-efficacy, which may lead to social isolation or avoiding physical activity [7, 8]. Because of these detrimental physical and psychological impacts on older people, falling is a major public health problem [6]. However, it is also known that up to 40 % of falls are potentially preventable [9]. Assessment of frailty should therefore lead to interventions to reduce falls.

Multiple longitudinal studies have previously investigated frailty as a predictor of future falls in community-dwelling older populations [10–20]. Most of them demonstrated that frail older people were more likely to fall than were their non-frail counterparts, [10–17] but a few studies did not [18–20]. Their follow-up periods were one year [10–14] or longer, up to eight years [17] and it is not known if frailty is predictive of future fall risk over a short period of follow-up.

The objective of this study was to examine the associations between baseline frailty status and short-term incidence of future falls among community-dwelling older people who participated in an exercise promotion trial. We hypothesised frailty would predict future falling during the short follow-up period of 24 weeks.

Methods

Study population

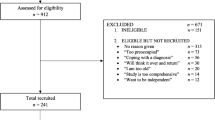

The cohort of this study consisted of British community-dwelling older people in the usual care arm of a randomised controlled trial conducted in London and Nottingham/Derby in 2008–2013 to examine the effects of two exercise programs [21]. Included in this trial were people age > =65 years who were able to walk independently and participate in group exercise classes without unstable medical conditions. They were excluded if they had three or more falls in the previous year or were exercising for 150 min or more per week. Trial participants were more physically active than the older population, with lower levels of comorbidity and polypharmacy [21]. This trial was approved by the Nottingham Research Ethics Committee 2, National Health Service Nottinghamshire County and Westminster, Brent, Harrow, Hounslow and Barnet & Enfield Primary Care Trusts and was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00726531) and ISRCTN (ISRCTN43453770). All participants provided written informed consent. Of a total of 1254 participants, 457 were allocated to the usual care arm. Those who did not return more than half of their falls diaries (n = 193) and those who had missing data on more than two variables out of 40 (5 %) for constructing the Frailty Index (FI) (n = 16) were excluded, leaving 248 participants for the analysis.

Predictor variable: Frailty

Frailty was measured using FI constructed based on 40 deficits at baseline [22]. Of 248 participants included in this study, 222, 25 and 1 had 40, 39 and 38 variables available, respectively, to construct FI. The deficits are symptoms, signs, disabilities and diseases that are biologically sensible, accumulate with age, do not peak too early and cover a range of systems [23]. Although there is no standard set of deficits to construct FI, it is recommended to use at least 30–40 variables to accurately predict adverse outcomes and FIs based on different deficits appear to yield similar results [23, 24]. The deficits used in this study included 16 physical limitations, including activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living, 15 comorbidities, four psychological symptoms and one deficit each for obesity, polypharmacy, general health, low activity and pain (Table 1). Dichotomised deficits were scored as 1 if the deficit was present and as 0 if absent, while continuous or ordinal deficits were given a score between 0 and 1 to represent severity of the deficits. Some of the deficits were derived from the 12-item Short Form Survey and the ConfBal Scale, [25, 26] which were asked at the baseline of the trial [21]. FI was calculated by adding the scores of the deficits and dividing by the total number of the deficits available for each participant. In case of missing data, missing variables were excluded from both numerator and denominator. For example, if a participant had information of 38 deficit variables available (two missing) and had five deficits out of the 38, FI was calculated as 5 divided by 38 equals 0.13. FI can range from 0 (no deficit) to 1 (maximum deficits possible). Frailty was defined as FI > =0.25 according to previous studies [27, 28].

Outcome variable: Future falls

For the purposes of this study, a fall was defined as an event of unintentionally coming to rest on the ground, floor, or other lower level [5]. Participants who had at least one fall during the 24-week follow-up period were defined as fallers and participants who did not have falls were defined as non-fallers. Falls were monitored prospectively over the study period using falls diaries. The falls diaries were mailed to each participant every four weeks, for a total of six diaries, and participants were required to record daily if they had fallen or not [29]. All participants who did not return the diary were reminded by a phone call.

Other covariates

Socio-demographic and clinical information collected at baseline included age, gender, height, weight, ethnicity, highest level of education achieved, annual household income and number of falls in the previous year. Height and weight were measured at the baseline examination and body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by square of height in meters.

Statistical analyses

Baseline socio-demographic characteristics were compared using Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables between fallers and non-fallers. The Spearman’s correlation coefficient was calculated to assess correlations between FI and the socio-demographic characteristics. Odds ratios (OR) with 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI) of frailty (dichotomous, FI > =0.25) and FI (continuous, per 0.01 increment) for future fall risks were calculated using logistic regression models, unadjusted and adjusted for age, gender and variables significantly associated with future falls in the univariate models. We used a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis to assess FI’s ability to predict future falls and calculated the area under the ROC curve (AUC). All statistical analyses were two-sided, with an alpha level of 0.05 and were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics (version 20, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Applying the FI to the study cohort identified 45 frail and 203 non-frail participants (Table 2). Frail participants were older, had a higher BMI, were more likely to live in Nottingham and have reported more falls in the previous year than non-frail participants.

Table 3 presents baseline characteristics of the study cohort and compares fallers and non-fallers. The mean age was 72.9 years old and 63.7 % were women. Of 248 participants, 46 (18.5 %) were classified as frail at baseline and 57 (23.0 %) had at least one fall during the 24-week study period. The mean FI was 0.16 (standard deviation 0.11) in the entire cohort. Fallers had higher mean FI (0.21) compared to non-fallers (0.14) and more fallers were classified as frail (19/57, 33.3 %) compared to non-fallers (27/191, 14.1 %). Given those who had had three or more falls in the previous 12 months were excluded at the time of the trial enrollment, all participants had had no or up to two falls in the previous 12 months. As expected, because a previous history of falls is a strong predictor of future falls, fallers were more likely to have fallen twice over the previous year (8/57, 14.0 %) than were non-fallers (5/191, 2.6 %). There were no significant differences between fallers and non-fallers in age, gender, BMI, ethnicity, education, income, enrollment site and the mean number of falls in the previous year.

Tables 4 and 5 show univariate and multivariate logistic regression models, respectively. Both frailty and FI at baseline were significantly associated with future falls during the follow-up period in univariate logistic regression models; each 0.01 increase in FI was associated with 5 % increased odds of future falls (OR = 1.05, 95 % CI = 1.02–1.07, p < 0.001) and those with frailty were approximately three times more likely to fall during the follow-up period than were those without (OR = 3.04, 95 % CI = 1.53–6.02, p = 0.001). In multivariate logistic regression models, the associations between frailty status and future falls persisted after adjusting for age, gender and history of two falls in the previous year (OR = 1.05, 95 % CI = 1.02–1.08, p = 0.001; OR = 2.95, 95 % CI = 1.41–6.17, p = 0.004, respectively).

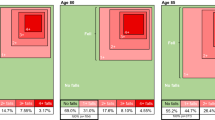

Figure 1 displays a ROC curve of FI as a predictor of future falls. In this population sample FI predicted future falls with fair accuracy with AUC of 0.62 (95 % CI = 0.53–0.71, p = 0.006). Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, positive likelihood ratio and negative likelihood ratio of using a FI of 0.25 as a cut-off point to define frailty, were 31.6 %, 85.9 %, 40.0 %, 80.8 %, 2.23 and 0.80, respectively.

Discussion

This study of 248 British community-dwelling older people demonstrated that frailty was a significant predictor of future falls during the short follow-up period of 24 weeks independent of history of falls, which is a strong predictor of falls risk, and other covariates.

In the literature, two previous studies using FI demonstrated significant associations between frailty and future falls after longer follow-up periods than this study [14, 17]. FI based on 34 deficits at baseline predicted incident falls during the third year in approximately 4000 women aged 55 years or older in Canada (OR = 1.02 for 0.01 increase in FI, 95 % = 1.02–1.03) [14]. Another study constructed FI using 33 deficits and divided a cohort of 3257 community-dwelling Chinese people from the Beijing Longitudinal Study of Aging study into five subgroups based on FI (<=0.03, 0.03–0.10, 0.10–0.20, 0.21–0.5 and >0.5). They showed that higher FI was associated with higher risk of recurrent falls over the subsequent eight years (OR = 1.54 for each FI subgroup increment, 95 % = 1.34–1.76) [17]. Unlike our study, these studies did not use a specific cut-off point to define frailty.

Frailty defined by other definitions, including a Fried’s phenotype,[11, 12, 15, 16] Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF) index,[11, 12, 15] Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam frailty instrument,[10] Canadian Study of Health and Aging Clinical Frailty Scale,[13] and Conselice Study of Brain Aging index [20] have also been shown to predict future falls in community-dwelling populations. Of these, two studies performed ROC curve analysis and showed AUC, based on Fried’s phenotype and SOF index, ranging from 0.61 to 0.63, which was comparable with our result using FI (AUC = 0.62) [11, 12].

The findings of this study need to be interpreted cautiously. This study was performed by a secondary analysis using data from the cohort originally recruited for an exercise intervention trial. The participants, who volunteered for the exercise intervention trial, may have been a selected group of people who were more motivated to exercise and adopted a healthy lifestyle. Therefore, our findings may not be completely generalisable. This is perhaps seen in the comparison of the cohort based on the FI (Table 2), where we may have expected female gender, lower income and lower education to have been significantly different between those identified as frail and those as non-frail, based on previous literature. However, these associations were not seen. We excluded frequent fallers, those who had three or more falls in the previous year, at the baseline, which may have led to underestimating the association between frailty and future fall risk. The most frequently used frailty definition, Fried’s phenotype, was not used to define frailty in this study due to the unavailability of necessary data. However, although it may be time-consuming to use FI in clinical practice as many of the deficit variables are not routinely collected, FI is another popular definition that has been examined and validated in various populations and settings and has been shown to predict mortality more accurately than does the Fried’s phenotype model [27]. A significant proportion, approximately 40 % (193/457), of participants allocated to the usual care arm returned between no and three falls diaries out of six and were therefore excluded. Compared with those who returned four to six diaries, the excluded participants were significantly frailer (mean FI 0.22 vs. 0.16, p < 0.001), which may have underestimated the fall risk. These two groups did not differ in mean age, gender, or history of two falls in the previous year. Lastly, we did not have data on some important potential confounders, such as cognitive function, alcohol use or high risk medication use, and could not control for these factors.

The major strength of this study is high quality incident fall data based on the comprehensive fall monitoring system. The standardised protocol included participant’s daily recordings in the falls diaries and the submission of the diaries at short intervals, along with follow-up reminder phone calls if necessary. Furthermore, only participants who returned more than half of the fall diaries were included in the analyses. These procedures may have contributed to minimising recall bias and avoiding underreporting falls [30].

Another strength are the clinical implications of our findings. This study cohort was derived from a large exercise intervention trial, where the participants were people aged over 65 years who were recruited in primary care and volunteered for the trial. Those at high risk for falling (i.e. with history of three or more falls in the previous year, unstable medical conditions, or mobility disability) were excluded. These relatively well older people without high risks for falling can be seen as “ageing well”. Nevertheless, among older people who are ageing well, frailty (defined as FI > =0.25) identified those with higher risk of falling in the next six months. This information may allow primary care physicians and geriatricians to intervene earlier in the falls trajectory, and researchers to design more effective exercise interventions or fall prevention programs [31].

Conclusions

In summary, frailty based on the deficit accumulation model of FI was a significant predictor of the short-term incidence of future falls among British community-dwelling older people. Given the fact falling can have negative impacts on older people, it is important for healthcare practitioners working with older people to recognise frailty as a risk factor for imminent falling, even in those who appear to be ageing well.

Abbreviations

- 95%CI:

-

95 % confidence interval

- AUC:

-

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- FI:

-

Frailty index

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- SOF:

-

Study of Osteoporotic Fractures

References

Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381(9868):752–62.

British Geriatrics Society. Fit for Frailty, Consensus best practice guidance for the care of older people living with frailty in community and outpatient settings [http://www.bgs.org.uk/campaigns/fff/fff_full.pdf].

Kojima G. Frailty as a Predictor of Future Falls Among Community-Dwelling Older People: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Med Direct Assoc. 2015;16(12):1027–33.

Swift CG, Iliffe S. Assessment and prevention of falls in older people - concise guidance. Clinical medicine (London, England). 2014;14(6):658–62.

Tinetti ME, Speechley M, Ginter SF. Risk factors for falls among elderly persons living in the community. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(26):1701–7.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US). Important Facts about Falls [http://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/falls/adultfalls.html].

Parry SW, Deary V, Finch T, Bamford C, Sabin N, McMeekin P, et al. The STRIDE (Strategies to Increase confidence, In Dependence and Energy) study: cognitive behavioural therapy-based intervention to reduce fear of falling in older fallers living in the community - study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15:210.

Kumar A, Carpenter H, Morris R, Iliffe S, Kendrick D. Which factors are associated with fear of falling in community-dwelling older people? Age Ageing. 2014;43(1):76–84.

Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, Sherrington C, Gates S, Clemson LM, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2012;9:CD007146.

de Vries OJ, Peeters GM, Lips P, Deeg DJ. Does frailty predict increased risk of falls and fractures? A prospective population-based study. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(9):2397–403.

Ensrud KE, Ewing SK, Cawthon PM, Fink HA, Taylor BC, Cauley JA, et al. A comparison of frailty indexes for the prediction of falls, disability, fractures, and mortality in older men. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(3):492–8.

Ensrud KE, Ewing SK, Taylor BC, Fink HA, Cawthon PM, Stone KL, et al. Comparison of 2 frailty indexes for prediction of falls, disability, fractures, and death in older women. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(4):382–9.

Wu TY, Chie WC, Yang RS, Liu JP, Kuo KL, Wong WK, et al. Factors associated with falls among community-dwelling older people in Taiwan. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2013;42(7):320–7.

Li G, Ioannidis G, Pickard L, Kennedy C, Papaioannou A, Thabane L, et al. Frailty index of deficit accumulation and falls: data from the Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW) Hamilton cohort. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:185.

Kiely DK, Cupples LA, Lipsitz LA. Validation and comparison of two frailty indexes: The MOBILIZE Boston Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(9):1532–9.

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–156.

Fang X, Shi J, Song X, Mitnitski A, Tang Z, Wang C, et al. Frailty in relation to the risk of falls, fractures, and mortality in older Chinese adults: results from the Beijing Longitudinal Study of Aging. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16(10):903–7.

Bandeen-Roche K, Xue QL, Ferrucci L, Walston J, Guralnik JM, Chaves P, et al. Phenotype of frailty: characterization in the women’s health and aging studies. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Med Sci. 2006;61(3):262–6.

Sheehan KJ, O’Connell MD, Cunningham C, Crosby L, Kenny RA. The relationship between increased body mass index and frailty on falls in community dwelling older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13:132.

Forti P, Rietti E, Pisacane N, Olivelli V, Maltoni B, Ravaglia G. A comparison of frailty indexes for prediction of adverse health outcomes in an elderly cohort. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;54(1):16–20.

Iliffe S, Kendrick D, Morris R, Masud T, Gage H, Skelton D, et al. Multicentre cluster randomised trial comparing a community group exercise programme and home-based exercise with usual care for people aged 65 years and over in primary care. Health technology assessment (Winchester, England). 2014;18(49):1–106.

Mitnitski AB, Mogilner AJ, Rockwood K. Accumulation of deficits as a proxy measure of aging. Sci World J. 2001;1:323–36.

Searle SD, Mitnitski A, Gahbauer EA, Gill TM, Rockwood K. A standard procedure for creating a frailty index. BMC Geriatr. 2008;8:24.

Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. Frailty in relation to the accumulation of deficits. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Med Sci. 2007;62(7):722–7.

Ware Jr J, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–33.

Simpson JM, Worsfold C, Hawke J. Balance confidence in elderly people. The CONFbal Scale (abstract 123). Age Ageing. 1998;27 Suppl 2:57.

Rockwood K, Andrew M, Mitnitski A. A comparison of two approaches to measuring frailty in elderly people. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Med Sci. 2007;62(7):738–43.

Song X, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. Prevalence and 10-year outcomes of frailty in older adults in relation to deficit accumulation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(4):681–7.

Perry L, Kendrick D, Morris R, Dinan S, Masud T, Skelton D, et al. Completion and return of fall diaries varies with participants’ level of education, first language, and baseline fall risk. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Med Sci. 2012;67(2):210–4.

Ganz DA, Higashi T, Rubenstein LZ. Monitoring falls in cohort studies of community-dwelling older people: effect of the recall interval. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(12):2190–4.

British Geriatrics Society. Fit for Frailty, Part 2: Developing, commissioning and managing services for people living with frailty in community settings [http://www.bgs.org.uk/campaigns/fff/fff2_full.pdf].

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment programme (project number 06/36/04). The views and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Health or the National Institute for Health Research. The sponsor had no role in study design, execution, analysis and interpretation of data and writing of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

GK and SI contributed the conception and design. DK, DAS, RWM, SG and SI acquired the data. GK and SI drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to analysis and interpretation of the data, revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kojima, G., Kendrick, D., Skelton, D.A. et al. Frailty predicts short-term incidence of future falls among British community-dwelling older people: a prospective cohort study nested within a randomised controlled trial. BMC Geriatr 15, 155 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-015-0152-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-015-0152-7