Abstract

Background

Antibiotic resistance is a problem in nursing homes. Presumed urinary tract infections (UTI) are the most common infection. This study examines urine culture results from elderly patients to see if specific guidelines based on gender or whether the patient resides in a nursing home (NH) are warranted.

Methods

This is a cross sectional observation study comparing urine cultures from NH patients with urine cultures from patients in the same age group living in the community.

Results

There were 232 positive urine cultures in the NH group and 3554 in the community group. Escherichia coli was isolated in 145 urines in the NH group (64 %) and 2275 (64 %) in the community group. There were no clinically significant differences in resistance.

Combined, there were 3016 positive urine cultures from females and 770 from males. Escherichia coli was significantly more common in females 2120 (70 %) than in males 303 (39 %)(p < 0.05). Enterococcus faecalis was significantly less common in females 223(7 %) than males 137 (18 %) (p < 0.05). For females, there were lower resistance rates to ciprofloxacin among Escherichia coli (7 % vs 12 %; p < 0.05) and to mecillinam among Proteus mirabilis (3 % vs 12 %; p < 0.05).

Conclusions

Differences in resistance rates for patients in the nursing home do not warrant separate recommendations for empiric antibiotic therapy, but recommendations based on gender seem warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Antibiotic resistance is a worldwide problem threatening our ability to treat infections [1]. Infections caused by multi-resistant bacteria are increasing among the elderly living in nursing homes (NH) [2–4]. The elderly are the age group with the highest prevalence of antibiotic use in Norway [5]. Anatomical and physiologic changes caused by aging [6, 7], usage of urinary catheters, nasogastric and percutaneous feeding tubes and intravenous catheters are common in NH, all predisposing to bacterial colonization and infections [8].

Urinary tract infections (UTI) are the most common infections among NH patients [9, 10]. However, a considerable proportion of antibiotic prescribing for presumed UTI is questionable. Treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB), and non-specific symptoms inaccurately interpreted to be caused by UTIs is prevalent in the NH despite no evidence of benefit and guidelines dissuading this practice [11–14]. Inappropriate antibiotic use is an important factor contributing to antibiotic resistance [1]. It is therefore necessary to optimize antibiotic prescribing for UTI in the institutionalized elderly. To accomplish this, knowledge of antibiotic resistance in the NH is essential.

Studies from abroad indicate that the bacterial etiology and resistance rates of UTI in NH patients resemble hospitalized patients more than they do the elderly living in the community [15, 16]. Results from a recent Australian study suggests that guidelines for empiric treatment of elderly patients with UTI should take into consideration differences in antibiotic resistance patterns in bacteria causing infections in the elderly living in NH versus the elderly living at home [17]. However, antibiotic resistance varies greatly between countries. Whether these findings are relevant in Norway or other countries is unknown.

Several articles address differences in the prevalence and microbiologic etiology of UTI in elderly women or men, but separate therapy suggestions based on gender are not specified [10, 18]. In addition, guidelines often lack specific recommendations based on gender in the elderly [19, 20].

We aim to assess whether the difference in resistance rates of bacteria isolated from NH patients compared to community dwelling elderly is so great that separate recommendations for empiric antibiotic therapy for UTI for the two groups is necessary. Second, we aim to assess if gender specific recommendations for antibiotic therapy of UTI are warranted in the elderly.

Methods

Setting/patients

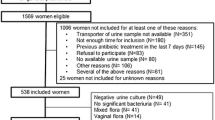

The laboratory for medical microbiology, Vestfold Hospital Trust serves the population of Vestfold County (240,000 inhabitants) [21]. NH patients resided in 34 different NHs in Vestfold County, were 65 years and older with a positive urine culture in the time period from 16. Nov 2009 through 31. Des 2010 (NH group). Results were compared to all positive urine cultures from non-hospitalized patients in Vestfold County 65 years or older not living at a NH in the same time period, the community dwelling group (CD). We registered both microbes when two microbes with significant bacteriuria were present.

Study design

The study is a cross-sectional observational study. The microbiologic laboratory registers all urines received for analysis and enters the patient’s full name, person number (unique for each person in Norway), address, the ordering physician and the institution (nursing home, hospital, private practice, emergency call service, visiting nurse service). In the CD group we excluded hospitalized patients, urines ordered by the visiting nurse service and urines taken in the emergency room.

Microbiologic analysis and susceptibility testing

Urine cultures fulfilling the criteria for significant bacteriuria (≥10,000 colony-forming units/mL urine) were included in the study. For Gram negative rods the automated method Vitek 2 (bioMérieux) was used. Appropriate antibiotics were selected for each bacterial species according to recommendations from the Norwegian Working Group on Antibiotics (NWGA) [22]. Results were interpreted according to clinical breakpoints from NWGA which are based on those from The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing EUCAST [23]. Dip-agar isolates and Gram positive bacteria were tested by disk diffusion technique (Oxoid) after the manufacturer’s recommendations. Resistance values were recorded either as susceptible (S), intermediate (I), or resistant (R).

Resistance data were extracted from the laboratory’s database.

Norwegian guidelines for empiric therapy for UTI in the nursing home [19]

ᅟ

Lower UTI: Pivmecillinam, trimethoprim, nitrofurantoin.

Upper UTI: Pivmecillinam, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin.

Outcomes

-

1.

Frequency and susceptibility of bacteria cultured in urine specimens.

-

2.

Susceptibility for each of the five most common uropathogens: Escherichia coli (E coli), Klebsiella pneumoniae (K pneumoniae), Proteus mirabilis (P mirabilis), Enterococcus faecalis (E faecalis), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P aeruginosa).

Calculating the theoretic risk of therapy failure

The theoretic risk of antibiotic failure depends on two factors; the prevalence of the microbes in the patient population and the resistance rate of these microbes to the chosen antibiotic [24]. We calculated the theoretical risk of therapy failure by multiplying the relative percentage each microbe was responsible for (e.g. for E coli 70.3 % for females and 39.4 % for males) with the resistance rate for that antibiotic (e.g. ciprofloxacin for E col; 7.2 % for females and 11.9 % for males). We performed these calculations for each of the five most commonly isolated microbes; E coli, E faecalis, K pneumoniae, P mirabilis, and P aeruginosa.

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS® statistics program was used for statistical analysis. We used a significance level of p < 0.05.

We used Pearson Chi2 test to compare differences in gender distribution between the NH group and the CD group and the t-test for independent samples to compare the mean age in the two groups.

We used the Pearson Chi2 test and the Fischer’s exact test (when appropriate) to compare differences in resistance rates for relevant antibiotics between the NH group and the CD group, and between males and females.

Ethical considerations

The study has been approved by the Norwegian regional ethics committee. The ethics committee waived the requirement for informed consent for this study. (REK sør-øst 2013/2282)

Results

There were 3786 bacteria isolates, 232 from NH patients and 3554 from CD patients. Females contributed 183 (78.9 %) and 2833 (79.7 %) and males 49 (21.1 %) and 721 (20.3 %) of the isolates to the NH and CD groups respectively (p =0.76).

The mean age of females in the NH group was 87.0 (SD 6.7; 95 % CI, 86.0-88.0) compared to 79.3 (SD 8.1; 95 % CI, 79.0-79.6) in the CD (p < 0.05). The mean age for males in the NH group was 83.1 (SD 6.2; 95 % CI, 81.3-84.9) compared to 78.0 (SD 7.6; 95 % CI, 77.8-78.9) in the CD group (p <0.05).

NH vs CD

There was no significant difference in the proportions of any of the bacteria between patients in the NH group and the CD group as a whole (Table 1). E coli was the most common and E faecalis the next most common pathogen isolated in both groups. In the category “Other bacteria”, no single bacterium contributed more than 2.5 % to the total in either the NH or the CD group.

E coli resistance rates were over 20 % for both ampicillin and trimethoprim in both groups (Table 2). The NH group showed a slightly though non-significantly higher resistance rate for ciprofloxacin than the CD group (9.5 vs 7.7 %). E faecalis resistance rates for trimethoprim were over 20 % in both groups but exhibited no resistance to ampicillin or nitrofurantoin in either group. K pneumoniae and P mirabilis resistance rates for ciprofloxacin were significantly higher in the NH group (p < 0.05).

Male vs female (irrespective of residence)

The difference in the relative frequency of which bacteria were isolated between males and females was highly significant (p < 0.05) (Table 1). For E coli there was a significantly higher resistance rates for ciprofloxacin for males than for females (p < 0.05). For P mirabilis there was a significantly higher resistance rates for mecillinam for males than for females (p < 0.05) (Table 3). There were no significant differences in resistance rates between males and females for E faecalis, K pneumoniae or P aeruginosa.

Theoretic risk of empiric therapy failure

For females the risk of failure was greater than twenty percent for ampicillin and trimethoprim. For males the risk of failure was greater than twenty percent for ampicillin, ciprofloxacin and mecillinam (Table 4).

Discussion

The differences between bacterial etiology and resistance rates among uropathogens isolated from elderly patients living in a NH and those living in the community were clinically unimportant. There is however a significant and clinically relevant difference between males and females both in terms of bacterial etiology and resistance rates.

Therapy decisions in empiric antibiotic therapy are educated guesses based on the relative prevalence of the microbes causing the infection and the resistance rates of these microbes. Guidelines for empiric antibiotic therapy consider both these factors and the severity of the infection. The sum of potentially inadequate coverage (e.g. mecillinam for P aeruginosa) or high resistance rates for a specific antibiotic (e.g. ampicillin for E coli) will influence recommendations for empiric therapy. Previous studies of urinary tract isolates from hospitalized patients with pyelonephritis and out-patients with uncomplicated UTI have shown that guidelines may need updating to be in concordance with local susceptibility rates [25–27].

Studies indicate increased bacterial resistance in bacteria causing UTI in the elderly living in health care facilities than in community acquired UTI and is similar to hospital acquired UTI [10, 15]. A recent Australian study suggested changes in empiric therapy recommendations for UTI due to higher resistance rates among Enterobacteriacea (E coli, K pneumoniae and P mirabilis) isolated in urine cultures from NH patients than in community dwelling elderly [17]. Our study also showed a higher rate of resistance for Enterobacteriacea in urine cultures from NH patients but comes to a different conclusion. The non-significantly higher rate of ciprofloxacin resistance in E coli from nursing home patients is far below the 20 % resistance rate normally used to dissuade the choice in empiric treatment for non-serious infections like cystitis. Because K pneumoniae and P mirabilis contribute minimally to the total number of UTI they do not result in a significantly higher risk of therapy failure in the NH despite the higher rates of resistance in these bacteria. Consequently, differences between culture results from the NH and the elderly living in the community do not warrant separate recommendations for empiric antibiotic therapy for cystitis.

Our results do, however, indicate that separate recommendations may be in order for males and females irrespective of where the patient resides. This is not surprising as the bacterial etiology of UTI differs between males and females, a finding reflected in other studies [10, 28]. Ciprofloxacin and mecillinam may be poor choices for empiric treatment for males due to a higher rate of ciprofloxacin resistance among E coli and a relatively high prevalence of E faecalis for which neither ciprofloxacin nor mecillinam are recommended. The higher prevalence of E faecalis in the elderly male population is a finding seen in other studies also [28, 29]. In addition, there are higher rates of mecillinam resistance among K pneumoniae and P mirabilis in males vs females. These results should be interpreted cautiously due to the uncertainty of catheter status. In the NH, use of permanent urinary catheters is more prevalent in males than in females [30]. Furthermore, bacteria from patients with urinary catheters have a higher rate of resistant organisms [31–33].

Trimethoprim may be a poor choice for females but acceptable in males due to the higher rate of E coli resistance in females than in males. Amoxicillin cannot be recommended for empiric therapy for either gender. Treatment of UTI should also take into consideration that even relatively high doses of trimethoprim or nitrofurantoin will not give high enough serum or tissue levels to result in cure for pyelonephritis or prostatitis infections especially if the infection is caused by E coli or other Enterobacteriacea species.

The rates of resistance shown in our study are similar to national surveillance rates in Norway, but are somewhat higher than a recent study of a NH in Sweden raising a question of the external validity of our study [31, 34]. A possible explanation for this is that our isolates were from patients having infections which were to be treated while the Swedish study examined urine from all patients able to provide a urine sample. This could potentially make the contribution of ASB higher in the Swedish study.

The concept of external validity is relevant when it comes to studies dealing with empiric antibiotic treatment because resistance problems vary substantially throughout the world. The theoretic model presented in Table 4 is based on local resistance patterns making the issue of its external validity salient. While the results here do not have relevance in other countries, the theoretic basis behind determining the risk of treatment failure is relevant anywhere by using local resistance data [24].

Earlier studies from Norway show lower resistance rates than in this study [35]. This change over time and the differences between the Swedish, Australian and our study illustrate the need for periodic national monitoring of resistance development to keep guideline recommendations up to date and reliable. Reliable guidelines are an important part of antibiotic stewardship but there are numerous barriers impairing adherence to guidelines [36, 37]. Lack of periodic surveillance can undermine the credibility of empiric therapy guidelines, and worse, result in therapy failure for patients.

There are several weaknesses in our study. We are uncertain about the compliance with the Norwegian guidelines outlining correct urine sampling technique in the two groups [38]. Urinary incontinence makes correct urine sampling challenging and is more prevalent in the NH than in the community [39]. Urinary catheter status was not reported systematically in either the NH group or the CD group making conclusions about the contribution of catheter associated infections impossible. Rates of inappropriate collection techniques and the prevalence of cultures from catheterized patients may be different in the two groups. Given this potential selection bias one might expect a higher rate of resistance and higher prevalence of pathogenic bacteria in the NH, but the results in our study show no such difference.

In the NH group, all culture results were from patients with suspected UTI treated with antibiotics. None of the NH urines were due to post-therapy control. Norwegian guidelines dissuade urine culturing for ASB and do not recommend routine post-therapy control [19]. Despite this, the CD group may be less homogeneous because we cannot ascertain the proportion of the culture results due to UTI, ASB or the contribution of post-therapy control cultures. In addition, the relative contribution of lower UTI and upper UTI in the two groups is not precisely known. As the incidence of dementia, use of catheters and urinary incontinence are higher in the NH setting one would expect the rate of complicated UVI inclusive pyelonephritis to be higher in this group [40].

Patients in the NH group were on average 10 years older than the CDs. Antibiotic resistance among uropathogens in general and for ciprofloxacin specifically is higher in the elderly [16, 40–42]. In this case having a younger CD group would contribute to making the difference in resistance rates between the two groups more obvious. That was not the case in this study.

Conclusion

In Norway, differences in resistance rates for patients 65 years and older living at home or in a nursing home do not warrant separate recommendations for empiric antibiotic therapy but recommendations based on gender seem warranted.

Abbreviations

- ASB:

-

Asymptomatic bacteriuria

- CD:

-

Community dwelling

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- E coli :

-

Escherichia coli

- E faecalis :

-

Enterococcus faecalis

- EUCAST:

-

European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

- K pneumoniae :

-

Klebsiella pneumoniae

- MIC:

-

Minimum inhibitory concentration

- NA:

-

Not applicable

- NH:

-

Nursing home

- NWGA:

-

Norwegian Working Group on Antibiotics

- P aeruginosa :

-

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- P mirabilis :

-

Proteus mirabilis

- Res:

-

100 % resistant

- UTI:

-

Urinary tract infection

References

Cars O, Hogberg LD, Murray M, Nordberg O, Sivaraman S, Lundborg CS, et al. Meeting the challenge of antibiotic resistance. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2008;337:a1438.

Nicolle LE, Strausbaugh LJ, Garibaldi RA. Infections and antibiotic resistance in nursing homes. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996;9:1–17.

Trick WE, Weinstein RA, DeMarais PL, Kuehnert MJ, Tomaska W, Nathan C, et al. Colonization of skilled-care facility residents with antimicrobial-resistant pathogens. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:270–6.

Wiener J, Quinn JP, Bradford PA, Goering RV, Nathan C, Bush K, et al. Multiple antibiotic-resistant Klebsiella and Escherichia coli in nursing homes. JAMA. 1999;281:517–23.

Litleskare I, Blix HS, Ronning M. [Antibiotic use in Norway]. Tidsskrift for den Norske laegeforening (The Journal of the Norwegian Medical Association). 2008;128:2324–9.

Saltzman RL, Peterson PK. Immunodeficiency of the elderly. Rev Infect Dis. 1987;9:1127–39.

Garibaldi RA, Brodine S, Matsumiya S. Infections among patients in nursing homes: policies, prevalence, problems. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:731–5.

Gammack JK. Use and management of chronic urinary catheters in long-term care: much controversy, little consensus. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2003;4:S52–9.

Fagan M, Maehlen M, Lindbaek M, Berild D. Antibiotic prescribing in nursing homes in an area with low prevalence of antibiotic resistance: compliance with national guidelines. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2012;30:10–5.

Nicolle LE, Long-Term-Care-Committee S. Urinary tract infections in long-term-care facilities. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2001;22:167–75.

Phillips CD, Adepoju O, Stone N, Moudouni DK, Nwaiwu O, Zhao H, et al. Asymptomatic bacteriuria, antibiotic use, and suspected urinary tract infections in four nursing homes. BMC Geriatr. 2012;12:73.

Nicolle LE, Bradley S, Colgan R, Rice JC, Schaeffer A, Hooton TM. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:643–54.

van Buul LW, Veenhuizen RB, Achterberg WP, Schellevis FG, Essink RT, de Greeff SC, et al. Antibiotic prescribing in dutch nursing homes: how appropriate is it? J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16:229-37.

Sundvall PD, Ulleryd P, Gunnarsson RK. Urine culture doubtful in determining etiology of diffuse symptoms among elderly individuals: a cross-sectional study of 32 nursing homes. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12:36.

Horcajada JP, Shaw E, Padilla B, Pintado V, Calbo E, Benito N, et al. Healthcare-associated, community-acquired and hospital-acquired bacteraemic urinary tract infections in hospitalized patients: a prospective multicentre cohort study in the era of antimicrobial resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:962–8.

Laupland KB, Ross T, Pitout JD, Church DL, Gregson DB. Community-onset urinary tract infections: a population-based assessment. Infection. 2007;35:150–3.

Xie C, Taylor DM, Howden BP, Charles PG. Comparison of the bacterial isolates and antibiotic resistance patterns of elderly nursing home and general community patients. Intern Med J. 2012;42:e157–64.

Rowe TA, Juthani-Mehta M. Diagnosis and management of urinary tract infection in older adults. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2014;28:75–89.

Lindbæk M, editor. Nasjonale faglige retningslinjer for antibiotikabruk i primærhelsetjenesten(Guidelines for the Use of Antibiotics in Primary Care). Oslo: Helsedirektoratet; 2012.

Guideline 88: Management of suspected bacterial urinary tract infection in adults. 2015. [http://www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/fulltext/88/index.html]. Accessed 08 Apr 2015.

Folkemengden - Årleg - Tabellar – SSB (Population-Annual tables. Statistics Norway) . 2014. [http://www.ssb.no/befolkning/statistikker/folkemengde/aar/2014-02-20?fane=tabell&sort=nummer&tabell=164157]. Accessed 08 Apr 2015.

Norwegian working group on antibiotics (Arbeidsgruppen for antibiotikaspørsmål (AFA) - Universitetssykehuset Nord-Norge) [http://www.unn.no/afa/category10274.html]. Accessed 08 Apr 2015.

European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network (EARS-Net) [http://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/activities/surveillance/EARS-Net/Pages/index.aspx]. Accessed 08 Apr 2015.

Davis ME, Anderson DJ, Sharpe M, Chen LF, Drew RH. Constructing unit-specific empiric treatment guidelines for catheter-related and primary bacteremia by determining the likelihood of inadequate therapy. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33:416–20.

Bosch FJ, van Vuuren C, Joubert G. Antimicrobial resistance patterns in outpatient urinary tract infections--the constant need to revise prescribing habits. S Afr Med J. 2011;101:328–31.

Spoorenberg V, Prins JM, Stobberingh EE, Hulscher ME, Geerlings SE. Adequacy of an evidence-based treatment guideline for complicated urinary tract infections in the Netherlands and the effectiveness of guideline adherence. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;32:1545–56.

Schmiemann G, Gagyor I, Hummers-Pradier E, Bleidorn J. Resistance profiles of urinary tract infections in general practice--an observational study. BMC Urol. 2012;12:33.

Lipsky BA. Urinary tract infections in men. Epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110:138–50.

Czaja CA, Scholes D, Hooton TM, Stamm WE. Population-based epidemiologic analysis of acute pyelonephritis. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:273–80.

Jonsson K, E-Son Loft AL, Nasic S, Hedelin H. A prospective registration of catheter life and catheter interventions in patients with long-term indwelling urinary catheters. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2011;45:401–5.

Sundvall PD, Elm M, Gunnarsson R, Molstad S, Rodhe N, Jonsson L, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in urinary pathogens among Swedish nursing home residents remains low: a cross-sectional study comparing antimicrobial resistance from 2003 to 2012. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14:30.

Jonsson K, Claesson BE, Hedelin H. Urine cultures from indwelling bladder catheters in nursing home patients: a point prevalence study in a Swedish county. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2011;45:265–9.

Tinelli M, Cataldo MA, Mantengoli E, Cadeddu C, Cunietti E, Luzzaro F, et al. Epidemiology and genetic characteristics of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Gram-negative bacteria causing urinary tract infections in long-term care facilities. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:2982–7.

NORM/NORM-VET 2012. Usage of Antimicrobial Agents and Occurrence of Antimicrobial Resistance in Norway. In: Book NORM/NORM-VET 2012. Usage of antimicrobial agents and occurrence of antimicrobial resistance in Norway. Tromsø; 2013

Skudal HK, Grude N, Kristiansen BE. [Increasing antibiotic resistance in urinary tract infections]. Tidsskrift for den Norske laegeforening (The Journal of the Norwegian Medical Association). 2006;126:1058–60.

Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud PA, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282:1458–65.

Nicolle LE. Antimicrobial stewardship in long term care facilities: what is effective? Antimicrobial Resistance Infection Control. 2014;3:6.

Veiledning i urinprøtaking v 1 1.pdf (Guidelines for urine sampling). Norwegian Quality Improvement of Primary Health Care Laboratories (NOKLUS) 2015. [http://www.noklus.no/Portals/2/Kurs%20og%20veiledning/Informasjonsmateriell/Veiledning%20i%20urinprøvetaking%20v%201%201.pdf]. Accessed 08 Apr 2015.

Durrant J, Snape J. Urinary incontinence in nursing homes for older people. Age Ageing. 2003;32:12–8.

Nicolle LE. Urinary tract pathogens in complicated infection and in elderly individuals. J Infect Dis. 2001;183 Suppl 1:S5–8.

Zhanel GG, Hisanaga TL, Laing NM, DeCorby MR, Nichol KA, Palatnik LP, et al. Antibiotic resistance in outpatient urinary isolates: final results from the North American Urinary Tract Infection Collaborative Alliance (NAUTICA). Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2005;26:380–8.

Linhares I, Raposo T, Rodrigues A, Almeida A. Frequency and antimicrobial resistance patterns of bacteria implicated in community urinary tract infections: a ten-year surveillance study (2000–2009). BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:19–9.

Acknowledgements

Deep thanks to Ibrahimu Mdala for statistical help and Svein Gjelstad for advice on the structuring of the SPSS file. Economic support for the project was provided by Major and advocat Eivind Ekbos Legat, Henrik Ibsens gate 100, PB 2933 Solli, 0230 Oslo, the Norwegian medical association’s family medicine research fund (AMFF), NORM - Norwegian Organization for Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance in Microbes (NORM). The sponsors were not involved in any part of the design, data collection, analysis, or manuscript preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

All authors have completed the ICMJE form. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors MF, ML. NG, HR, MR, DS and DB participated in the design of the study. ML, MR and DS collected the data. MF analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. MF, ML. NG, HR, MR, DS and DB contributed to the interpretation of the analyses, critical reviews, revisions, and final approval of the paper.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Fagan, M., Lindbæk, M., Grude, N. et al. Antibiotic resistance patterns of bacteria causing urinary tract infections in the elderly living in nursing homes versus the elderly living at home: an observational study. BMC Geriatr 15, 98 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-015-0097-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-015-0097-x