Abstract

Background

Distinguishing strangulated bowel obstruction (StBO) from simple bowel obstruction (SiBO) still poses a challenge for emergency surgeons. We aimed to construct a predictive model that could distinctly discriminate StBO from SiBO based on the degree of bowel ischemia.

Methods

The patients diagnosed with intestinal obstruction were enrolled and divided into SiBO group and StBO group. Binary logistic regression was applied to identify independent risk factors, and then predictive models based on radiological and multi-dimensional models were constructed. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and the area under the curve (AUC) were calculated to assess the accuracy of the predicted models. Via stratification analysis, we validated the multi-dimensional model in the prediction of transmural necrosis both in the training set and validation set.

Results

Of the 281 patients with SBO, 45 (16.0%) were found to have StBO, while 236(84.0%) with SiBO. The AUC of the radiological model was 0.706 (95%CI, 0.617–0.795). In the multivariate analysis, seven risk factors including pain duration ≤ 3 days (OR = 3.775), rebound tenderness (OR = 5.201), low-to-absent bowel sounds (OR = 5.006), low levels of potassium (OR = 3.696) and sodium (OR = 3.753), high levels of BUN (OR = 4.349), high radiological score (OR = 11.264) were identified. The AUC of the multi-dimensional model was 0.857(95%CI, 0.793–0.920). In the stratification analysis, the proportion of patients with transmural necrosis was significantly greater in the high-risk group (24%) than in the medium-risk group (3%). No transmural necrosis was found in the low-risk group. The AUC of the validation set was 0.910 (95%CI, 0.843–0.976). None of patients in the low-risk and medium-risk score group suffered with StBO. However, all patients with bowel ischemia (12%) and necrosis (24%) were resorted into high-risk score group.

Conclusion

The novel multi-dimensional model offers a useful tool for predicting StBO. Clinical management could be performed according to the multivariate score.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Small bowel obstruction (SBO) is a common disease, accounting for 12%-16% of all surgical admissions in the United States[1]. SBO can be divided into simple bowel obstruction (SiBO) and strangulated bowel obstruction (StBO). SiBO is usually resolved by nonoperative management, including bowel rest, nasogastric tubes and tube decompression, reducing the risk of emergency surgery[2]. Conversely, StBO requires immediate surgical intervention[3], as StBO may result in severe complications, including bowel perforation, peritonitis and septic shock, which increase the mortality of SBO up to 25%[4, 5]. In the case of bowel transmural necrosis, the mortality dramatically increases to 50%[6]. However, only 1/3 of StBO patients have the classical traits of abdominal pain, hematochezia and fever, and the remaining patients have nonspecific symptoms such as diarrhea, vomiting and bloating[7]. Consequently, it is difficult to accurately diagnose and intervene in StBO in the early stage. How to distinguish StBO from SiBO still poses a challenge to emergency surgeons.

Traditionally, clinical findings serve as major models for the prediction of StBO[8,9,10]; however, the accuracy of these models remains unsatisfactory[11]. More focus has been placed on radiological characteristics[12,13,14], whereas the diagnostic performance of CT revealed poor prospective prediction[8, 15]. CTA (computed tomography angiography) is the gold standard of predicting bowel ischemia with 83–100% sensitivity and 61–93% specificity[16]. However, CTA is rarely performed in emergency situations due to its high cost, insufficient medical support, potential allergic reaction and high risk of nephropathy induced by iodine[17,18,19]. In previous studies for the detection of laboratory biomarkers to evaluate StBO, only L-lactate was deemed an effective biomarker for the prediction of bowel ischemia, with 78% sensitivity and 48% specificity[6, 20]. Therefore, predictive models integrating clinical features, laboratory tests and radiological characteristics need to be studied for the prediction of StBO.

To date, few studies have focused on the prediction of bowel transmural necrosis for SBO, most of which enrolled patients with acute mesenteric ischemia (AMI)[21,22,23]. Among these studies, only laboratory biomarkers were primarily considered indicative factors of bowel transmural necrosis[21, 22]. To our knowledge, no efforts have been made to predict transmural necrosis in patients with SBO. Therefore, a multi-dimensional model to predict transmural necrosis in patients with SBO is urgently needed.

In this study, we constructed an accurate predictive model consisting of clinical features, laboratory tests and radiological characteristics for the diagnosis of StBO. Based on the predictive model, we could distinctly discriminate StBO from SiBO, especially for transmural necrosis from simple bowel ischemia.

Methods

Patient population

We divided patients in our cohort into two group including training set and validation set. In the training set, from October 2016 to February 2021, 479 patients diagnosed with intestinal obstruction at Fujian Medical University Union Hospital were included in the retrospective study. After excluding 180 patients with large bowel obstruction, 4 patients with missing CT images and 13 patients with incomplete clinical data, 281 patients were recruited in the final study (shown in Fig. 1). For the validation set, 80 patients diagnosed as intestinal obstruction accepted treatment in our unit from March 2021 to Mar 2022.

The patients were divided into two groups according to the pathological confirmation of intestinal ischemia: a simple bowel obstruction (SiBO) group and a strangulated bowel obstruction (StBO) group. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Fujian Medical University Union Hospital (FJMUUH), and all patients provided written informed consent for the procedure.

Clinical characteristics and laboratory tests

Clinical parameters, including pain duration, symptoms of abdominal pain, tenderness, rebound tenderness, and bowel sounds, and laboratory tests, including white blood cell count (WBC), prothrombin time (PT), and potassium, sodium, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and D-dimer (DDI) levels, were recorded in our database for intestinal bowel obstruction. Categorical variables, especially potassium, sodium, BUN, PT and DDI levels, were transformed from continuous variables according to laboratory references[24,25,26,27,28]. The levels of WBC and NE%, were sorted by quartile. In addition, procalcitonin (PCT) levels were divided into three categories based on a previous study[20].

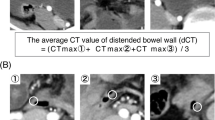

CT findings

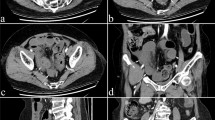

All patients with suspected SBO underwent CT scans before receiving treatment. The features of the CT scans recorded in this study were separated into mesenteric fluid, ascites, spiral signs, concentric circle signs, small bowel feces signs, and edema of the bowel wall[4, 29,30,31,32,33]. All CT scan images were cross-reviewed and judged by two senior radiologists (radiologist Lin Lin had 10 years of experience in abdominal radiology, and radiologist Ying-qian Geng had 8 years of experience in general radiology). The discriminate portions were independently judged by a general surgeon, Xian-qiang Chen who had over 10 years of experience in abdominal emergency surgery. The definitions of CT characteristics were showed in Fig. 2 and supplied in Additional file 1: Table S2.

Images of CT findings. A a 49-year-old woman with adhesive small bowel obstruction. Axial CT of the abdomen confirmed the spiral sign of small bowel (red arrow). B a 51-year-old man with adhesive small bowel obstruction. Axial CT of the pelvis confirmed the small bowel feces sign(red arrow) and the mesenteric fluid (white triangle). C a 51-year-old man with inflammatory small bowel obstruction. Dilated, thickened loops of small bowel (red arrow) and mesenteric fluid (white triangle) could be observed. D a 70-year-old woman with intussusception. Axial CT images showed the concentric circle sign of small bowel (red arrow) and ascites (white triangle)

Statistical analysis

The differences between the two groups were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. For continuous variables, we used an independent t-test. For continuous nonparametric variables, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was adopted to analyze the differences between the groups. Independent risk factors including pain duration, rebound tenderness, bowel sounds, levels of potassium, sodium, BUN and radiological score, were finally confirmed via binary logistic regression and none of them showed feature correlation via co-linearity analysis. We also extracted a risk score formula based on the seven independent risk factors. RS = [1.328 ×(pain duration level) + 1.649 ×(rebound tenderness level) + 1.611 ×(bowel sounds level) + 1.307 ×(potassium level) + 1.323 ×(sodium level) + 1.470 ×(BUN level) + 2.422 ×(Radiological score) − 6.009]. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and the area under the curve (AUC) were calculated to assess the accuracy of the predicted models. A logistic nomogram was generated by using tools in Hiplot (https://hiplot.com.cn), a comprehensive web platform for scientific data visualization. The other statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software (SPSS, version 23.0, SPSS Inc.).

Results

Background and clinical-laboratory features

Of the 281 patients with SBO who were included in this study, 45 (16.0%) were found to have StBO, while 236 (84.0%) were found to have SiBO. No remarkable differences were observed between the groups for the baseline parameters, including age, sex, BMI, and comorbidity status (all p value > 0.05, Table 1). Via univariate analysis, several clinical characteristics, including pain duration (p = 0.036), abdominal pain (p = 0.018), tenderness (p = 0.020), rebound tenderness (p < 0.001), and bowel sounds (p = 0.014), were significantly different between the two groups. High levels of inflammatory biomarkers, such as WBC (p = 0.029) and NE% (p = 0.007), and abnormal electrolyte and metabolic changes, such as low levels of sodium (p = 0.009), abnormal potassium (p = 0.003), and high levels of BUN (p < 0.001) and glucose (p = 0.002), were closely related to bowel ischemia. In the validation set, rebound tenderness degree (p < 0.001), the level of WBC (p = 0.029) and NE% (p = 0.007) also significantly deteriorated in the StBO group compared with SiBO group (Additional file 1: Table S7).

Univariate and multivariate analyses of radiological characteristics

Through univariate analysis of the radiological characteristics, we determined that StBO was closely related to the presence of mesenteric fluid (p = 0.018), ascites (p = 0.002), bowel spiral signs (p < 0.001) and edema of the bowel wall (p = 0.037) (Table 2). Via binary logistic regression analysis, we defined only ascites (OR = 4.067, 95% CI: 1.506–10.983, p = 0.006) and bowel spiral signs (OR = 5.506, 95% CI: 2.609–11.623, p < 0.001) as independent risk factors for StBO. Similarly, ascites (p = 0.003) and bowel spiral signs(p = 0.080) also obviously manifested in StBO group in the validation set(Additional file 1: Table S7).

Based on the results of multivariate analysis, we built a radiological scoring system to predict the occurrence of StBO. The area under the curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for this model was 0.706 (95% CI, 0.617–0.795) (Fig. 3). Furthermore, we observed that the discriminative ability of this model was better when comparing the radiological score of the 2 group with the score of the 0 group (54.5% vs. 6.6%). However, it was difficult to separate the radiological score of the 1 group from the score of the 0 group (12.8% vs. 6.6%) (Additional file 1: Table S3.).

Multi-dimensional analysis and model construction

Furthermore, we analyzed all essential factors (p value < 0.05) from clinical characteristics, laboratory tests and radiological characteristics via binary logistic regression. To obtain better discrimination ability, we transformed three factors, bowel sounds, potassium level and radiological score, into two categories of variables. Finally, we found that pain duration (OR = 3.775), rebound tenderness (OR = 5.201), bowel sounds (OR = 5.006), levels of potassium (OR = 3.696), sodium (OR = 3.753) and BUN (OR = 4.349) and radiological score (OR = 11.264) were independent risk factors for the prediction of StBO (p value < 0.05, Table 3). Based on the regression coefficient for each factor, we constructed a multi-dimensional model with an AUC value of 0.857 (95% CI: 0.793–0.920) (Fig. 4. A, model formula is shown in Fig. 7). A nomogram was also drawn to directly calculate the probability of the occurrence of StBO (Fig. 5). As the risk factors accumulated, the incidence of StBO dramatically increased.

Validation of multi-dimensional models for the prediction of StBO

Patients were further divided into three groups based on the fourth quartile of the multi-dimensional model scores: a low-risk group (risk scores ≤ − 3.091, n = 71), a medium risk group (− 3.091 < risk scores ≤ − 1.472, n = 130) and a high-risk group (risk scores > − 1.472, n = 67). Obviously, strangulated bowel was rarely observed in patients in the low-risk group (1%), but it was strongly associated with patients in the high-risk group (45%) (Fig. 5). The predictive value for the two cutoff points was as follows: a sensitivity of 97.6% and specificity of 40.0% for a lower score (− 3.091) and a sensitivity of 71.4% and specificity of 83.6% for a score of − 1.472. Moreover, to evaluate the properties of the model for predicting the degree of ischemia, we stratified the patients into a simple bowel ischemia group and a transmural necrosis group. The proportion of patients with transmural necrosis was significantly greater in the high-risk group (24%) than in the medium-risk group (3%). No transmural necrosis was found in the low-risk group (Fig. 6A and B).

In the validation set, The AUC of this multi-dimensional models was 0.910 (95%CI, 0.843–0.976) (Fig. 4.B). None of patients in the low-risk and medium-risk score group suffered with StBO. However, all patients with bowel ischemia (12%) and necrosis (24%) were resorted into high-risk score group (Fig. 6C).

Discussion

SBO is always a dilemma for emergency surgeons in providing care. First, delayed surgery for StBO leads to severe complications such as intestinal ischemia, necrosis, perforation, peritonitis, sepsis, and multiple organ failure, with a dramatically increased mortality of 20–40%[34]. However, unnecessary surgery for SiBO may aggravate the formation of adhesive bands with subsequent adherence and its potential sequelea[29]. The prompt and accurate diagnosis of StBO still poses challenges for clinicians.

Previous studies have confirmed the discriminative efficacy of CT findings in the diagnosis of StBO, especially the presence of mesenteric fluid, ascites, edema of the bowel wall and whirl signs in CTA[12, 13, 21, 35]. Similarly, in our radiological analysis, mesenteric fluid, ascites, bowel spiral signs and edema of the bowel wall in emergency CT scans seemed closely related to StBO. Based on multivariate analysis, only ascites and bowel spiral signs were independent risk factors for StBO. This might be due to the classical characteristics of high metabolic activity and terminal artery perfusion in the small intestine mucosa. In the presence of mechanical SBO with mesenteric spirals, the permeability of the impaired mucosa increases[29, 33], which results in the transudative loss of fluid from the lumen into the peritoneal cavity. According to our etiology analysis, volvulus and hernias occupied a greater proportion of factors in StBO than in SiBO (Additional file 1: Table S1). Moreover, with the stasis of intestinal contents and bowel dilation, it may evolve into low or absent bowel sounds when SBO is aggravated, which could account for low-to-absent bowel sounds as an independent risk factor for StBO. The AUC of the radiological model based on emergency CT scans in our study reached only 0.706. In addition, CTA has been recommended as the gold standard for the diagnosis of bowel ischemia, with AUCs ranging from 0.87 to 0.91[8, 36]. The limitations include the potential risk of nephropathy induced by iodine, high costs and unavailability for most primary medical institutions[17], which hamper the performance of CTA.

Furthermore, we developed a multi-dimensional model based on clinical features, laboratory tests and radiological characteristics for the prediction of StBO. Once strangulated bowel develops, with increasing translocation of bacterial products from the intestinal lumen to blood circulation, a severe inflammatory response, including leukocytosis and neutrophilia, tends to occur[33, 37]. Similar to our findings, the levels of WBC and NE% were much higher in the StBO group, and the symptom of peritonitis with rebound tenderness was confirmed as an independent risk factor for StBO. An imbalance between the absorption and secretion of impaired intestinal mucosa also triggers electrolyte disturbances[2, 38]. In our multi-dimensional model, we defined hyponatremia, hypokalemia and rising levels of BUN as independent risk factors for StBO. In addition, insufficient renal perfusion due to extrasecretion in the intestinal lumen and the accumulation of lactic acid produced by intestinal anaerobic glycolysis deteriorate renal function with increasing levels of BUN in peripheral blood[22, 39]. Consequently, the distal convoluted tubule response to aldosterone results in the reabsorption of Na + by exchanging K + or H + , thus, hyponatremia and hypokalemia occur[2]. Usually, unlike a long pain duration indicating a chronic and reversible phase of disease, a short pain duration might indicate a status of acute and severe inflammation. Comprehensively, we constructed a multi-dimensional model for the prediction of StBO based on seven risk factors, including a radiological score, pain duration, bowel sounds, rebound tenderness, and the levels of sodium, potassium and BUN. The AUC of this multi-dimensional model was 0.857 (95% CI: 0.793–0.920), which was much higher than that of the model that only consisted of radiological characteristics[15] and equal to that of the previous CTA model[8, 36] (Additional file 1: Table S5). According to a previous study, we calculated the scores of our multi-dimensional model by summing the respective regression coefficients of the risk factors[22]. The formula is shown in Fig. 7. Furthermore, a nomogram was also constructed to reveal the weights for each factor, and radiological characteristics played a dominant role in predicting StBO. Secondary to radiological characteristics, the clinical symptoms were found to be crucial factors in the prediction of StBO.

Recently, most studies have focused on the prediction of bowel transmural necrosis in AMI[22, 23, 40], and few studies have focused on StBO. Although great advancements have been made in the detection of novel biomarkers associated with bowel ischemia[41,42,43,44,45], only I-FABP and PCT have been focused on in the prediction of bowel transmural necrosis with unsatisfactory accuracy[44, 45]. Here, by stratifying all patients into low-risk, medium-risk and high-risk groups according to their multi-dimensional scores (Fig. 6), we revaluated the discriminative ability of the multi-dimensional model for the prediction of transmural necrotic bowel obstruction. Excitedly, our models showed great efficacy not only for identifying patients with StBO but also recognizing transmural necrosis. Patients with bowel ischemia were primarily observed in the high-risk group, and the proportion of patients with bowel transmural necrosis was significantly higher than that in the medium-risk group. No transmural necrosis cases were found in the low-risk group. Only one patient in the low-risk group developed bowel ischemia without necrosis (Additional file 1: Table S4), which proved mild ischemia in this case. Additionally, another four patients with bowel transmural necrosis were observed in the medium-risk group. Although the specificity of our model largely improved with the rising score endpoint, there inevitably existed a loss of sensitivity, which is a shortcoming of the model. However, aggressive exploration is of greater importance than passively waiting for patients to show signs of suspected bowel transmural necrosis. Constant and dynamic observation is also necessary for patients in the low- or medium-risk group. This predictive model also well performed in our validation set.

The limitations of the present study are as follows. First, this study was a retrospective study conducted in a single center. Second, some parameters may not be identified due to the small-scale sample. Moreover, the validation for the multi-dimensional model is an internal validation only. Further efforts are needed in large-scale and prospective studies and effective external validations.

Conclusion

The novel multi-dimensional model consisting of risk factors for pain duration, rebound tenderness, bowel sounds, potassium, sodium, and BUN levels and radiological characteristics offers a useful tool for predicting StBO. Clinical management can be performed according to the multi-dimensional score; for patients with low risk (scores ≤ − 3.91), conservative treatment is recommended. For the high-risk group (risk scores > − 1.472), there was a strong suggestion for detection with laparotomy. For the remaining patients (− 3.091 < risk scores ≤ − 1.472), dynamic observation is suggested.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this study are included within the article. Corresponding to Junrong Zhang and Xianqiang Chen when necessary.

Abbreviations

- StBO:

-

Strangulated bowel obstruction

- SiBO:

-

Simple bowel obstruction

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- AMI:

-

Acute mesentery ischemia

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- WBC:

-

White blood cell

- NE%:

-

Neutrophil percentage

- PCT:

-

Procalcitonin

- BUN:

-

Blood urea nitrogen

- PT:

-

Prothrombin time

- DDI:

-

D-dimer

- CTA:

-

Computed tomography angiography

References

Maung AA, Johnson DC, Piper GL, Barbosa RR, Rowell SE, Bokhari F, et al. Evaluation and management of small-bowel obstruction: an Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma practice management guideline. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(5 Suppl 4):S362–9.

Chinglensana L, Salam SS, Saluja P, Priyabarta Y, Sharma MB. Small bowel obstruction- clinical features, biochemical profile and treatment outcome. J Evol Med Dent Sci. 2018;7(26):2972–6.

Cevikel MH, Ozgun H, Boylu S, Demirkiran AE, Aydin N, Sari C, et al. C-reactive protein may be a marker of bacterial translocation in experimental intestinal obstruction. ANZ J Surg. 2004;74(10):900–4.

Chang WC, Ko KH, Lin CS, Hsu HH, Tsai SH, Fan HL, et al. Features on MDCT that predict surgery in patients with adhesive-related small bowel obstruction. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2):e89804.

Paulson EK, Thompson WM. Review of small-bowel obstruction: the diagnosis and when to worry. Radiology. 2015;275(2):332–42.

Studer P, Vaucher A, Candinas D, Schnuriger B. The value of serial serum lactate measurements in predicting the extent of ischemic bowel and outcome of patients suffering acute mesenteric ischemia. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19(4):751–5.

Dhatt HS, Behr SC, Miracle A, Wang ZJ, Yeh BM. Radiological evaluation of bowel ischemia. Radiol Clin North Am. 2015;53(6):1241–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcl.2015.06.009.

Schwenter F, Poletti PA, Platon A, Perneger T, Morel P, Gervaz P. Clinicoradiological score for predicting the risk of strangulated small bowel obstruction. Br J Surg. 2010;97(7):1119–25.

Ozawa M, Ishibe A, Suwa Y, Nakagawa K, Momiyama M, Watanabe J, et al. A novel discriminant formula for the prompt diagnosis of strangulated bowel obstruction. Surg Today. 2021;51(8):1261–7.

Huang X, Fang G, Lin J, Xu K, Shi H, Zhuang L. A Prediction model for recognizing strangulated small bowel obstruction. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2018;2018:7164648.

Kim JH, Ha HK, Kim JK, Eun HW, Park KB, Kim BS, et al. Usefulness of known computed tomography and clinical criteria for diagnosing strangulation in small-bowel obstruction: analysis of true and false interpretation groups in computed tomography. World J Surg. 2004;28(1):63–8.

Millet I, Taourel P, Ruyer A, Molinari N. Value of CT findings to predict surgical ischemia in small bowel obstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Radiol. 2015;25(6):1823–35.

Zielinski MD, Eiken PW, Heller SF, Lohse CM, Huebner M, Sarr MG, et al. Prospective, observational validation of a multivariate small-bowel obstruction model to predict the need for operative intervention. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212(6):1068–76.

Cox VL, Tahvildari AM, Johnson B, Wei W, Jeffrey RB. Bowel obstruction complicated by ischemia: analysis of CT findings. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2018;43(12):3227–32.

Sheedy SP, Ft E, Fletcher JG, Fidler JL, Hoskin TL. CT of small-bowel ischemia associated with obstruction in emergency department patients: diagnostic performance evaluation. Radiology. 2006;241(3):729–36.

Furukawa A, Kanasaki S, Kono N, Wakamiya M, Tanaka T, Takahashi M, et al. CT diagnosis of acute mesenteric ischemia from various causes. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192(2):408–16.

Nijssen EC, Rennenberg RJ, Nelemans PJ, Essers BA, Janssen MM, Vermeeren MA, et al. Prophylactic hydration to protect renal function from intravascular iodinated contrast material in patients at high risk of contrast-induced nephropathy (AMACING): a prospective, randomised, phase 3, controlled, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10076):1312–22.

Mitchell AM, Kline JA, Jones AE, Tumlin JA. Major adverse events one year after acute kidney injury after contrast-enhanced computed tomography. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;66(3):267-74 e4.

Moos SI, van Vemde DN, Stoker J, Bipat S. Contrast induced nephropathy in patients undergoing intravenous (IV) contrast enhanced computed tomography (CECT) and the relationship with risk factors: a meta-analysis. Eur J Radiol. 2013;82(9):e387–99.

Cosse C, Sabbagh C, Kamel S, Galmiche A, Regimbeau JM. Procalcitonin and intestinal ischemia: a review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(47):17773–8.

Kulvatunyou N, Pandit V, Moutamn S, Inaba K, Chouliaras K, DeMoya M, et al. A multi-institution prospective observational study of small bowel obstruction: clinical and computerized tomography predictors of which patients may require early surgery. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79(3):393–8.

Zhuang X, Chen F, Zhou Q, Zhu Y, Yang X. A rapid preliminary prediction model for intestinal necrosis in acute mesenteric ischemia: a retrospective study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021;21(1):154.

Emile SH. Predictive factors for intestinal transmural necrosis in patients with acute mesenteric ischemia. World J Surg. 2018;42(8):2364–72.

Winter WE, Flax SD, Harris NS. Coagulation testing in the core laboratory. Lab Med. 2017;48(4):295–313.

Favresse J, Lippi G, Roy PM, Chatelain B, Jacqmin H, Ten Cate H, et al. D-dimer: preanalytical, analytical, postanalytical variables, and clinical applications. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2018;55(8):548–77.

Hosten AO. BUN and Creatinine. In: Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, editors. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. Boston: Butterworths.

Copyright © 1990, Butterworth Publishers, a division of Reed Publishing.; 1990.

Kardalas E, Paschou SA, Anagnostis P, Muscogiuri G, Siasos G, Vryonidou A. Hypokalemia: a clinical update. Endocr Connect. 2018;7(4):R135–46.

Spasovski G, Vanholder R, Allolio B, Annane D, Ball S, Bichet D, et al. Clinical practice guideline on diagnosis and treatment of hyponatraemia. Eur J Endocrinol. 2014;170(3):G1-47.

Zielinski MD, Eiken PW, Bannon MP, Heller SF, Lohse CM, Huebner M, et al. Small bowel obstruction-who needs an operation? A multivariate prediction model. World J Surg. 2010;34(5):910–9.

Kim J, Lee Y, Yoon JH, Lee HJ, Lim YJ, Yi J, et al. Non-strangulated adhesive small bowel obstruction: CT findings predicting outcome of conservative treatment. Eur Radiol. 2021;31(3):1597–607.

Hwang JY, Lee JK, Lee JE, Baek SY. Value of multidetector CT in decision making regarding surgery in patients with small-bowel obstruction due to adhesion. Eur Radiol. 2009;19(10):2425–31.

Ishikawa E, Kudo M, Minami Y, Ueshima K, Kitai S, Ueda K. Cecal intussusception in an adult with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome relieved by colonoscopy. Intern Med. 2010;49(12):1123–6.

Rami Reddy SR, Cappell MS. A systematic review of the clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of small bowel obstruction. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2017;19(6):28.

Hayakawa K, Tanikake M, Yoshida S, Yamamoto A, Yamamoto E, Morimoto T. CT findings of small bowel strangulation: the importance of contrast enhancement. Emerg Radiol. 2013;20(1):3–9.

Aufort S, Charra L, Lesnik A, Bruel JM, Taourel P. Multidetector CT of bowel obstruction: value of post-processing. Eur Radiol. 2005;15(11):2323–9.

Millet I, Boutot D, Faget C, Pages-Bouic E, Molinari N, Zins M, et al. Assessment of strangulation in adhesive small bowel obstruction on the basis of combined CT findings: implications for clinical care. Radiology. 2017;285(3):798–808.

Grootjans J, Thuijls G, Verdam F, Derikx JP, Lenaerts K, Buurman WA. Non-invasive assessment of barrier integrity and function of the human gut. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;2(3):61–9.

Grootjans J, Lenaerts K, Buurman WA, Dejong CHC, Derikx JPM. Life and death at the mucosal-luminal interface: New perspectives on human intestinal ischemia-reperfusion. World J Gastroentero. 2016;22(9):2760–70.

Baum N, Dichoso CC, Carlton CE. Blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine. Physiol Interpret Urol. 1975;5(5):583–8.

Acosta-Merida MA, Marchena-Gomez J, Cruz-Benavides F, Hernandez-Navarro J, Roque-Castellano C, Rodriguez-Mendez A, et al. Predictive factors of massive intestinal necrosis in acute mesenteric ischemia. Cir Esp. 2007;81(3):144–9.

Guzel M, Sozuer EM, Salt O, Ikizceli I, Akdur O, Yazici C. Value of the serum I-FABP level for diagnosing acute mesenteric ischemia. Surg Today. 2014;44(11):2072–6.

Powell A, Armstrong P. Plasma biomarkers for early diagnosis of acute intestinal ischemia. Semin Vasc Surg. 2014;27(3–4):170–5.

Ayten R, Dogru O, Camci C, Aygen E, Cetinkaya Z, Akbulut H. Predictive value of procalcitonin for the diagnosis of bowel strangulation. World J Surg. 2005;29(2):187–9.

Markogiannakis H, Memos N, Messaris E, Dardamanis D, Larentzakis A, Papanikolaou D, et al. Predictive value of procalcitonin for bowel ischemia and necrosis in bowel obstruction. Surgery. 2011;149(3):394–403.

Peoc’h K, Corcos O. Biomarkers for acute mesenteric ischemia diagnosis: state of the art and perspectives. Ann Biol Clin (Paris). 2019;77(4):415–21.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff of the Department of General surgery (Emergency surgery) of Fujian Medical University Union Hospital, for their guidance and support.

Funding

This work was supported by Fujian Provincial Young and Middle-aged Key Talents Training Project [grant numbers: 2020GGA034 to Xian-qiang Chen]; the Innovation Training and Entrepreneurship Plan for College Students of Fujian Medical University [grant number: C21045 to Jun-rong Zhang]; the Joint Funds for the Innovation of Science and Technology, Fujian province [grant numbers: 2018Y9006 to Jun-rong Zhang, 2018Y9054 to Xian-qiang Chen]; Startup Fund for Scientific Research, Fujian Medical University [grant number: 2019QH1016 to Ping Hou].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: JZ, WX and XC; Data curation: WX, QZ, YC, and CZ; Formal analysis: JZ, WX, and SC; Funding acquisition: JZ, PH and XC; Investigation: WX, QZ, YC, and CZ; Methodology: JZ, LL, YG, XC and HW; Project administration: XC, JZ and WX; Resources: JZ, PH, XC; Software: JZ and WX; Supervision: XC; Validation: WX, QZ, YC, and CZ; Visualization: JZ, QZ and WX; Roles/Writing—original draft: JZ and WX; Writing—review and editing: JZ, WX.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Our study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Fujian Medical University Union Hospital (FJMUUH), and all patients provided written informed consent for the procedure, following. The Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file1

: Table S1. The etiology of small bowel obstruction. Table S2. The definitions for CT findings. Table S3. The discriminative effectiveness of CT score. Table S4. Analyzation of the negative predicting results. Table S5. Previous studies on predictive model. Table S6. Treatments and outcomes of all patients. Table S7. Comparison of the clinical and radiological characteristics of the patients in external validation set.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, Wx., Zhong, Qh., Cai, Y. et al. Prediction and management of strangulated bowel obstruction: a multi-dimensional model analysis. BMC Gastroenterol 22, 304 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-022-02363-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-022-02363-1