Abstract

Background

Single-operator, per-oral cholangiopancreatoscopy (SOPCP) enables direct biliopancreatic ductal visualization, targeted tissue sampling, and therapeutic intervention. At Karolinska University Hospital, SOPCP was introduced early and has since been extensively utilized according to a standardized protocol. We analysed the clinical value of SOPCP in the diagnosis and treatment of biliopancreatic diseases in a single high volume center.

Methods

All SOPCP procedures performed between March 2007 and December 2014 were retrospectively reviewed. Each procedure’s diagnostic yield and therapeutic value was evaluated using a predefined 4 grade scale; 1 - no diagnostic or therapeutic value, 2 - information gained did not impact clinical decision-making and in case of a therapeutic intervention, did not alter the clinical course of the patient, 3 - information gained had an impact on clinical decision-making and in the case of a therapeutic intervention, assisted subsequent disease management, and finally, 4 - information gained was essential and critical for clinical decision-making and in case of a therapeutic intervention, solved the clinical problem requiring no further therapeutic actions. Descriptive statistics were used to analyse results, with uni- and multivariate analyses completed to assess risk of adverse events.

Results

During the study period, 365 SOPCP procedures were performed. We found SOPCP of pivotal importance (grade 4) in 19% of cases, and of great clinical significance (grade 3) in 44% of cases. SOPCP did not affect clinical decision-making or alter clinical course (grade 1 and 2) in 37% of cases.

Conclusion

SOPCP offers direct access to the biliopancreatic ducts for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes, adding significant clinical value in 64% of cases.

Trial registration

As this is a purely observational and retrospectively registered study in which the assignment of the medical intervention was not at the discretion of the investigator, it has not been registered in a registry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Technological advancement in recent years has led to per-oral cholangiopancreatoscopy emerging as a solution to the challenge of diagnosis and treatment in the small and relatively inaccessible biliopancreatic ductal systems. As an adjunct to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), it can be performed in one of three ways [1]; dual-operator or mother-baby cholangioscopy, direct per-oral cholangioscopy, or single-operator (catheter-based) cholangiopancreatoscopy (SOPCP). There is an international trend towards the use of the single-operator system, mainly due to ease of use [2]. The SpyGlass Direct Visualization System (Boston Scientific, USA) makes use of a standard duodenoscope, enabling a single operator to insert specially designed optical fibres via an optical port, with two further available ports, one for irrigation and the other to function as a working channel for insertion of the biopsy forceps, lithotripsy fibres or laser probe [3].

The use of SOPCP has been evaluated both for the diagnosis of indeterminate bile duct strictures, as well as for the treatment of ‘difficult’ bile duct stones [4,5,6,7,8,9]. It has recently been successfully utilized in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), enabling targeted biopsies and navigation of otherwise inaccessible strictures [10]. Additionally, it offers unique options for visualization, surveillance and early-detection of premalignant lesions in pancreatic ductal epithelium, being particularly relevant for lesions such as intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN) [11,12,13,14,15,16].

Since its introduction, SOPCP has been met with divergent experiences; on the one hand it is considered to be a valuable diagnostic and therapeutic tool, with the other extreme the view that it might represent a dangerous acquisition of redundant information. Although procedural success when using SOPCP has been established [7, 17], and adverse events described [2], the degree to which SOPCP specifically alters clinical management remains to be investigated. At Karolinska University Hospital, SOPCP has been utilized since 2007, following a standardized protocol. Accordingly, we have collected a substantial longitudinal experience. This report critically analyzes our data, focusing on the clinical utility of this technology in the diagnosis and treatment of biliopancreatic disease.

Methods

From 2007 to 2014, all patients undergoing SOPCP with the SpyGlass Direct Visualization System at the Karolinska University Hospital, were included for study. Unless the indication for investigation was complex cholelithiasis, all patients were discussed at a multidisciplinary team meeting, where an individualized management plan was decided on. Complex cholelithiasis was defined as either ‘difficult’ to remove common bile duct stones (stone removal not achieved by conventional means), or intrahepatic stones. Baseline demographics included a physical status grading according to the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification system where grades indicate the presence of; I – a normal healthy patient, II – mild systemic disease, III – severe systemic disease, and IV – systemic disease a constant threat to life. Each procedure’s diagnostic yield and therapeutic value was retrospectively reviewed using a predefined graded scale as follows; 1 - no diagnostic or therapeutic value, 2 - information gained did not impact clinical decision-making and in case of a therapeutic intervention, did not alter the clinical course of the patient, 3 - information gained had an impact on clinical decision-making and in case of a therapeutic intervention, assisted subsequent disease management, and finally, 4 - information gained was essential and critical for clinical decision-making and in case of a therapeutic intervention, solved the clinical problem requiring no further diagnostic or therapeutic actions. The scale was applied to each individual case by a single independent reviewer, and the final decision as to the assigned grade was made by determining the impact the procedure had on the final multidisciplinary team meeting decision.

All patients routinely received antibiotic prophylaxis consisting of either intravenous piperacillin+tazobactam or oral sulfonamid+trimethoprim, administered prior to the ERCP. According to standard endoscopy suite protocol, prophylactic non-steroidal anti-inflammatories were not administered and in PSC patients brush samples for cytology and flow cytometry [10] were obtained. Detailed criteria for tissue sampling of strictures by mini-forceps were not defined, and SOPCP-guided biopsies were taken at the discretion of the endoscopist whenever suspicious focal findings were present.

All procedures were carried out under general anaesthesia with the SpyGlass Direct Visualization System (Boston Scientific, USA) passed through a standard duodenoscope. The first generation Spyglass System consists of three components; firstly a reusable SpyGlass fibre optic probe (allowing direct visual guidance and examination of the respective duct systems), secondly the SpyScope disposable access and delivery catheter system (capable of accommodating both optical and accessory devices used in the biliary system), and finally the disposable mini-biopsy forceps (used to capture tissue specimens for histomorphologic diagnosis). The fibre optic probe has an outer diameter of 0.9 mm, image transmission of 6000 pixels, a 0O direct view, and a field view of 70o. The light source is a Xenon light connected to the SpyScope catheter. Electrohydraulic lithotripsy was performed using either a 1.9-Fr coaxial electrode probe (Olympus Lithotron EL-25, 1000 mJ; Olympus Inc., Stockholm, Sweden) or Nortech AUTOLITH® EHL-generator with 1,9 F bipolar biliary EHL probe (Northgate Technologies Inc. Elgin, IL, USA).

After successful cannulation of the papilla and positioning of the guide wire into the ductal system under investigation, a ductogram was obtained. An endoscopic sphincterotomy was performed in all patients. In case of an insufficient previous sphincterotomy, a redo sphincterotomy was performed. The Spyglass system was then carefully advanced into the relevant duct, with saline irrigation used for clearance of debris.

In patients with indeterminate strictures, SOPCP was applied for visually targeted biopsies in cases where intraductal papillary and nodular structures or irregular mucosal surfaces could be visualized. The presence of dilated tortuous or irregular tumor vessels, if present, was information that could be added to the clinical data in each case, and was taken into account at subsequent multidisciplinary discussion. For the endoscopic diagnosis of IPMN, previously defined criteria were used [13, 15]. When discrete, circumscribed areas containing finger like protrusions, mucus or tumour vessels were identified, biopsy specimens were obtained from several different parts of the lesion under direct vision. In the absence of discrete lesions, random samples from the ductal epithelium were taken and sent for examination by a pathologist. In many of these patients brush cytology specimens were also obtained.

Intra- and postprocedural adverse events were graded according to the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) severity grading system [18].

Descriptive statistics were used such as frequencies, median values, and ranges. Uni- and multivariate analyses were done to address risk factors for the occurrence of postprocedural adverse events. All analyses were carried out using STATA 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA).

The study protocol was approved by the regional research ethics committee at Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden (dn 2014/55–31/4).

Results

During the 7-year period, 365 Spyglass procedures were completed in 311 patients. Demographic details of patients undergoing SOPCP are represented in Table 1. The majority of patients had only one procedure. The median duration of SOPCP was 99 min (range 50–275 min), including procedures such as ERCP and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) performed during the same anaesthetic. This suggests a certain degree of complexity and time needed for completion.

Specific indications for patients undergoing SOPCP are shown in Table 2. The main indication was indeterminate bile duct strictures in non-PSC patients. Complex cholelithiasis, was an indication for the procedure in only 16% of the cases. In 71% of our patients, the bile duct was the main target, the pancreatic duct in 24%, and both ducts in 5%.

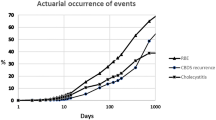

In 291 (79.6%) patients the procedure could be performed in an outpatient setting. Intra- and post procedural adverse events are presented in Table 3. We found an overall adverse event rate (AER) of 16%, with the majority of these being scored as mild or moderate.

The most frequent adverse event was pancreatitis in 8% of cases, with an equal distribution between mild and moderate pancreatitis. We were unable to demonstrate a change over time regarding the risk for this complication. Cholangitis was recorded in 16 patients (4%), of which no cases were severe. We experienced one fatal adverse event which was due to severe pancreatitis. In this patient an endoscopic ultrasound-guided puncture of a cystic pancreatic lesion had been performed in combination with the SOPCP. Initially a gastro-intestinal perforation was suspected, but this could not be verified on imaging. The clinical course was complex, ending in multi-organ failure and death on day 101. The subsequent autopsy revealed severe necrotizing pancreatitis.

When analysing specific risk factors for the occurrence of postprocedural adverse events, we found that pancreatoscopy was associated with an AER of 19.8% as compared to 9.6% for cholangioscopy. In the pancreatoscopy group we furthermore found a non-dilated main pancreatic duct in 9 of the 17 pancreatitis cases (53%).

When the clinical value of the respective SOPCP procedures were carefully scrutinised, a significant gain (grade 3–4) was detected in 64% of the cases (Fig. 1). The largest number of grade 2 procedures were due to an inability to definitively ascertain the relative contribution of the information provided by the SOPCP, in the presence of multiple factors that ultimately affected the clinical decision making process (n = 54).

Table 4 is a representation of the assigned grades (grouped as grade 1–2, or grade 3–4) according to the individual indications for SOPCP. In 79% of procedures performed for the treatment of complex bile duct stones, therapeutic value was graded as 3–4, whereas in 66% of procedures performed as part of work-up for cystic pancreatic lesions, diagnostic yield was graded as 3–4. For the evaluation of indeterminate biliary strictures, both in non-PSC and PSC patients, the diagnostic yield was graded as 3–4 in 57 and 56% of cases respectively. The clinical value of SOPCP in patients with chronic pancreatitis was graded as 1–2 in 55% of patients.

Discussion

Our study represents the largest single institution experience in the use of the SOPCP (SpyGlass) technique in routine clinical practice. Our results suggest it offers important options for direct intraluminal visual inspection, with the added possibility of targeted biopsies and therapeutic intervention in both the biliary (71%), and the pancreatic (23%) ductal systems. SOPCP significantly impacted or solved the clinical problem in 64% of the cases. The currently used grading system for diagnostic and therapeutic yield of SOPCP carries a risk of bias towards grade 3–4 scoring, and this issue will have to be addressed in a future validation study to establish inter-observer reliability. A significant caveat accompanying the use of SOPCP, is the 16% risk of adverse events.

The Spyglass System was first devised and clinically tested in 2005–2006 by Chen and Pleskow [17]. Since then, various groups have reported their initial experience, although numbers are often small, data collection retrospective and outcome measures varied. Procedural success has consistently been reported by most investigators to be above 90% [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26].

The most frequent indication for SOPCP in our patient population was the characterisation of indeterminate biliary strictures, one of the most challenging tasks clinicians are often faced with. Conventional methods of investigation such as cross-sectional imaging, as well as emerging modalities such as endoscopic ultrasonography and intraductal ultrasonography, are plagued with diagnostic uncertainty. Attempts at tissue sampling during ERCP with either brush cytology and/or ERCP-directed biopsy, have not yielded consistent results [27,28,29,30,31]. Two recent meta-analyses defined the sensitivity and specificity of SOPCP to diagnose indeterminate strictures [4, 32]. Both revealed a high sensitivity of visual impression (84.5–90%) for evaluating strictures as malignant, with a high specificity for SpyBite biopsy (98%) as confirmation. One of the limitations with analyses attempting to define diagnostic capability, is the possible lack of a ‘gold standard’ for verification of the diagnosis. Accordingly, with benign strictures of the bile duct, such as PSC, corroborating histology is usually unavailable. In 56–57% of our patients undergoing SOPCP for the evaluation of indeterminate bile duct strictures, the attributed clinical value was graded as high (grade 3–4). Our results are consistent with previously published data indicating the persistent diagnostic challenge regarding indeterminate strictures, but the final assessment of the diagnostic precision of the system, has to be further elucidated within the frame of large prospective series with adequate standards for comparison.

An important therapeutic indication for cholangioscopy is the treatment of ‘difficult’ bile duct stones, where duct clearance cannot be achieved by conventional means. A recent meta-analysis on the overall performance of all types of peroral cholangioscopy reported a stone clearance rate of 88% for bile duct stones [33]. Both electrohydraulic and holmium laser lithotripsy can be delivered via the SpyGlass system, and in our study complex cholelithiasis was the indication in 16% of cases. Although this is a small percentage of the total SOPCP cohort in out experience, in 79% of these procedures the therapeutic value of SOPCP was graded as high (grade 3–4). While our results draw attention to the established role of cholangioscopy in the treatment of complex biliary stone disease, it also suggests least therapeutic benefit for stones associated with chronic pancreatitis.

In our experience the most common indication for pancreatoscopy was a cystic lesion of the pancreas, including IPMN, and in 66% of these procedures, diagnostic yield was high (grade 3–4). The malignant potential of cystic lesions of the pancreas is notoriously difficult to accurately determine from conventional investigation methods, leading to complex decision making when choosing a treatment strategy [34, 35]. In patients with established or suspected IPMN we observed that at the time of pancreatoscopy, intraductal accumulation of mucous was a consistent finding.

There are certain technical limitations that warrant discussion. This study evaluates the first generation of the Spyglass system, where image quality has been one of the major drawbacks. The development of high-definition video technology will certainly enhance image quality [36]. Considering the current constraints, visualization can be optimized by free irrigation of saline, and adequate suctioning and drainage via a generous sphincterotomy.

Pancreatitis was the most frequent adverse event after SOPCP in our study, and like others [2, 20, 23, 37], we acknowledge this risk. It is not surprising that introduction of the device into, and manipulation inside of the main pancreatic duct emerged as a significant risk factor for post procedural pancreatitis. In our experience, irrigation with saline is necessary to clear the endoscopic view, and gentle handling and careful advancement of the device through the central parts of the main duct is mandatory to avoid damage. Although not allowing for further statistical analysis, a significant number of cases that developed pancreatitis had a main pancreatic duct with a normal diameter. Whether other procedure related factors play a role in the risk for pancreatitis is still unknown. One lethal adverse event is serious enough to highlight the need for careful dissemination of this technology outside of dedicated, specialized centers. Future studies will further our understanding of how adverse event risk can be minimized.

Our study was not a prospectively controlled analysis, but rather observational in design, assessing data from consecutive patients undergoing SOPCP. This can introduce bias toward visual impression, if the clinical history and results of prior investigations are known to the endoscopist. However, because we are scrutinising a new and evolving technical procedure, we believe that the endoscopist should have as much clinical information available as possible to maximize diagnostic and therapeutic yield at the time of the investigation.

Conclusion

SOPCP offers unique information from intraluminal visual inspection and therapeutic intervention of the biliary (71%) and pancreatic ducts (23%), but is burdened by a 16% risk of adverse events. We found the procedure to have significant clinical value in 64% of cases, firmly establishing its role as an important diagnostic and therapeutic adjunct to ERCP, and mandating further careful and critical exploration.

Abbreviations

- AER:

-

Adverse event rate

- ASA:

-

American Society of Anesthesiologists

- ASGE:

-

American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

- ERCP:

-

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

- EUS:

-

Endoscopic ultrasound

- IPMN:

-

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms

- PSC:

-

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

- SOPCP:

-

Single-operator cholangiopancreatoscopy

References

Hoffman A, Rey JW, Kiesslich R. Single operator choledochoscopy and its role in daily endoscopy routine. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;5(5):203–10.

Lubbe J, Arnelo U, Lundell L, Swahn F, Tornqvist B, Jonas E, et al. ERCP-guided cholangioscopy using a single-use system: nationwide register-based study of its use in clinical practice. Endoscopy. 2015;47(9):802–7.

Chen YK. Preclinical characterization of the Spyglass peroral cholangiopancreatoscopy system for direct access, visualization, and biopsy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65(2):303–11.

Navaneethan U, Hasan MK, Lourdusamy V, Njei B, Varadarajulu S, Hawes RH. Single-operator cholangioscopy and targeted biopsies in the diagnosis of indeterminate biliary strictures: a systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82(4):608–14 e2.

Chen YK, Parsi MA, Binmoeller KF, Hawes RH, Pleskow DK, Slivka A, et al. Single-operator cholangioscopy in patients requiring evaluation of bile duct disease or therapy of biliary stones (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74(4):805–14.

Kalaitzakis E, Webster GJ, Oppong KW, Kallis Y, Vlavianos P, Huggett M, et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic utility of single-operator peroral cholangioscopy for indeterminate biliary lesions and bile duct stones. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24(6):656–64.

Maydeo A, Kwek BE, Bhandari S, Bapat M, Dhir V. Single-operator cholangioscopy-guided laser lithotripsy in patients with difficult biliary and pancreatic ductal stones (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74(6):1308–14.

Patel SN, Rosenkranz L, Hooks B, Tarnasky PR, Raijman I, Fishman DS, et al. Holmium-yttrium aluminum garnet laser lithotripsy in the treatment of biliary calculi using single-operator cholangioscopy: a multicenter experience (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79(2):344–8.

Weber A, Schmid RM, Prinz C. Diagnostic approaches for cholangiocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(26):4131–6.

Arnelo U, von Seth E, Bergquist A. Prospective evaluation of the clinical utility of single-operator peroral cholangioscopy in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Endoscopy. 2015;47(08):696–702.

Arnelo U, Siiki A, Swahn F, Segersvärd R, Enochsson L, del Chiaro M, et al. Single-operator pancreatoscopy is helpful in the evaluation of suspected intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN). Pancreatology. 2014;14(6):510–4.

Atia GN, Brown RD, Alrashid A, Halline AG, Helton WS, Venu RP. The role of pancreatoscopy in the preoperative evaluation of intraductal papillary mucinous tumor of the pancreas. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35(2):175–9.

Del Chiaro M, Verbeke C, Salvia R, Klöppel G, Werner J, McKay C, et al. European experts consensus statement on cystic tumours of the pancreas. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45(9):703–11.

Kim JH, Hong SS, Kim YJ, Kim JK, Eun HW. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas: differentiate from chronic pancreatits by MR imaging. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81(4):671–6.

Tanaka M, Fernández-del Castillo C, Adsay V, Chari S, Falconi M, Jang J, et al. International consensus guidelines 2012 for the management of IPMN and MCN of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2012;12(3):183–97.

Vullierme MP, d'Assignies G, Ruszniewski P, Vilgrain V. Imaging IPMN: take home messages and news. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2011;35(6–7):426–9.

Chen YK, Pleskow DK. SpyGlass single-operator peroral cholangiopancreatoscopy system for the diagnosis and therapy of bile-duct disorders: a clinical feasibility study (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65(6):832–41.

Cotton PB, Eisen GM, Aabakken L, Baron TH, Hutter MM, Jacobson BC, et al. A lexicon for endoscopic adverse events: report of an ASGE workshop. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71(3):446–54.

Byrne M, Gerke H, Mitchell R, Stiffler H, McGrath K, Branch M, et al. Yield of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of bile duct lesions. Endoscopy. 2004;36(08):715–9.

Itoi T, Sofuni A, Itokawa F, Kurihara T, Tsuchiya T, Ishii K, et al. Initial experience of peroral pancreatoscopy combined with narrow-band imaging in the diagnosis of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66(4):793–7.

Kawakubo K, Isayama H, Sasahira N, Kogure H, Takahara N, Miyabayashi K, et al. Clinical utility of single-operator cholangiopancreatoscopy using a SpyGlass probe through an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography catheter. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27(8):1371–6.

Krishna SG, McElreath DP, Rego RF. Direct pancreatoscopy with an ultrathin forward-viewing endoscope in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(12):e75–6.

Miura T, Igarashi Y, Okano N, Miki K, Okubo Y. Endoscopic diagnosis of intraductal papillary-mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas by means of peroral pancreatoscopy using a small-diameter videoscope and narrow-band imaging. Dig Endosc. 2010;22(2):119–23.

Ramchandani M, Reddy DN, Gupta R, Lakhtakia S, Tandan M, Darisetty S, et al. Role of single-operator peroral cholangioscopy in the diagnosis of indeterminate biliary lesions: a single-center, prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74(3):511–9.

Siddiqui AA, Mehendiratta V, Jackson W, Loren DE, Kowalski TE, Eloubeidi MA. Identification of cholangiocarcinoma by using the Spyglass Spyscope system for peroral cholangioscopy and biopsy collection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10(5):466–71 quiz e48.

Sung KF, Chu YY, Liu NJ, Hung CF, Chen TC, Chen JS, et al. Direct peroral cholangioscopy and pancreatoscopy for diagnosis of a pancreatobiliary fistula caused by an intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas: a case report. Dig Endosc. 2011;23(3):247–50.

Fritscher-Ravens A, Broering D, Knoefel W, Rogiers X, Swain P, Thonke F, et al. EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration of suspected hilar cholangiocarcinoma in potentially operable patients with negative brush cytology. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(1):45–51.

Glasbrenner B, Ardan M, Boeck W, Preclik G, Möller P, Adler G. Prospective evaluation of brush cytology of biliary strictures during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Endoscopy. 1999;31(09):712–7.

Howell DA, Parsons WG, Jones MA, Bosco JJ, Hanson BL. Complete tissue sampling of biliary strictures at ERCP using a new device. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43(5):498–502.

Ponchon T, Gagnon P, Berger F, Labadie M, Liaras A, Chavaillon A, et al. Value of endobiliary brush cytology and biopsies for the diagnosis of malignant bile duct stenosis: results of a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42(6):565–72.

Rösch T, Hofrichter K, Frimberger E, Meining A, Born P, Weigert N, et al. ERCP or EUS for tissue diagnosis of biliary strictures? A prospective comparative study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60(3):390–6.

Sun X, Zhou Z, Tian J, Wang Z, Huang Q, Fan K, et al. Is single-operator peroral cholangioscopy a useful tool for the diagnosis of indeterminate biliary lesion? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82(1):79–87.

Korrapati P, Ciolino J, Wani S, Shah J, Watson R, Muthusamy VR, et al. The efficacy of peroral cholangioscopy for difficult bile duct stones and indeterminate strictures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy International Open. 2016;4(03):E263–75.

Fong ZV, Ferrone CR, Lillemoe KD, Fernandez-Del Castillo C. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas: current state of the art and ongoing controversies. Ann Surg. 2016;263(5):908–17.

Robles EP, Maire F, Cros J, Vullierme M, Rebours V, Sauvanet A, et al. Accuracy of 2012 international consensus guidelines for the prediction of malignancy of branch-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. United European Gastroenterol J. 2016;4(4):580–6.

Ishida Y, Itoi T, Okabe Y. Types of Peroral Cholangioscopy: how to choose the Most suitable type of Cholangioscopy. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2016;14(2):210–9.

Seth E, Arnelo U, Enochsson L, Bergquist A. Primary sclerosing cholangitis increases the risk for pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Liver Int. 2015;35(1):254–62.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The study was supported by a grant through a regional agreement on clinical research between Stockholm County Council and Karolinska Institutet (ALF 20130512), the Bengt Ihre fund, as well as the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC).

Availability of data and materials

The dataset generated and analysed during the study is stored in a secure localized research database and is available from the corresponding author in an anonymous format on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MR – Acquisition of data, analysis of data, drafting of manuscript, design of the study. JL – Analysis of data, literature review, drafting of the manuscript. LE - Performed procedures, interpretation of data, performed statistical analysis. LL – Critical revision of manuscript, design of the study. MK – Drafting of manuscript, acquisition of data. FS – Critical revision of manuscript, acquisition of data, performed procedures. MDC – Design of the study, critical review of manuscript. ML – Design of the study, critical revision of manuscript, performed procedures. UA – Design of the study, interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript, performed procedures. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the regional research ethics committee at Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden (dn 2014/55–31/4). Consent to participate was waived due to the fact that this is a purely observational study with no risk to participants, where the research will not affect the rights or welfare of the participants, and where the research could not be performed without a waiver of consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Reuterwall, M., Lubbe, J., Enochsson, L. et al. The clinical value of ERCP-guided cholangiopancreatoscopy using a single-operator system. BMC Gastroenterol 19, 35 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-019-0953-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-019-0953-9