Abstract

Background

Helicobacter pylori (H.pylori) infections are prevalent and recognized as major cause of gastrointestinal diseases in Ethiopia. However, Studies conducted on the prevalence, risk factors and other clinical forms of H.pylori on different population and geographical areas are reporting conflicting results. Therefore, this review was conducted to estimate the pooled prevalence of H.pylori infections and associated factors in Ethiopia.

Methods

PubMed, Embase, Google scholar, and Ethiopian Universities’ repositories were searched following the Preferred Items for Systematic review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guideline. The quality of included studies was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale in meta-analysis. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed using Cochrane Q test and I2 test statistics based on the random effects model. Comprehensive meta-analysis (CMA 2.0) and Review Manager (RevMan 5.3) were employed to compute the pooled prevalence and summary odds ratios of factors associated with of H.pylori infection.

Results

Thirty seven studies with a total of 18,890 participants were eligible and included in the analysis. The overall pooled prevalence of H.pylori infection was 52.2% (95% CI: 45.8–58.6). In the subgroup analysis by region, the highest prevalence was found in Somalia (71%; 95% CI: 32.5–92.6) and the lowest prevalence was reported in Oromia (39.9%; 95% CI: 17.3–67.7). Absence of hand washing after toilet (OR = 1.8, 95% CI; 1.19–2.72), alcohol consumption (OR = 1.34, 95% CI; 1.03–1.74) and gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms (OR = 2.23, 95% CI; 1.59–3.14) were associated with H.pylori infection. The trend of H.pylori infection showed a decreasing pattern overtime from 1990 to 2017 in the meta-regression analysis.

Conclusion

The prevalence of H.pylori infection remains high; more than half of Ethiopians were infected. Although the trend of infection showed a decreasing pattern; appropriate use of eradication therapy, health education primarily to improve knowledge and awareness on the transmission dynamics of the bacteria, behavioral changes, adequate sanitation, population screening and diagnosis using multiple tests are required to reduce H.pylori infections. Recognizing the bacteria as a priority issue and designing gastric cancer screening policies are also recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Helicobacter pylori have been found to infect about half of the world’s population [1,2,3,4,5]. The prevalence of H.pylori infection varies globally with a greater prevalence generally reported from developing countries. The global estimate of H.pylori infection was reported at 48.5% while continental reports were 69.4% in South America, 37.1% in North America, 24.4% in Oceania, 54.6% in Asia, 47.0% in Europe and 79.1% in Africa [2, 6]. This difference has been related to geography, age, ethnicity, socioeconomic factors, and methods of diagnosis and eradication therapy [1, 6, 7]. Diseases associated with H.pylori infections are commonly occur at earlier ages in developing countries [1,2,3, 8,9,10].

The burden of H.pylori infections goes beyond the gastrointestinal tract and associated with different complications including hyperemesis gravidarum [11], coronary heart disease [12, 13], anemia [14,15,16,17], diabetes mellitus [18,19,20,21,22], cholecystitis [23, 24], HIV [25,26,27], growth trajectories [28], autoimmune and Parkinson’s disease [29]. Failure to H.pylori eradication therapy is also linked to bacterial resistance and poor patient compliance [30,31,32,33,34].

In 2017, World Health Organization (WHO) has published lists of 16 bacteria that pose the greatest risk for human health. H.pylori was thus categorized as a high priority pathogen for research and development of new and effective treatments [35]. In addition, recommendations are emerging to change approaches to management of H.pylori due to increased drug resistance [30, 31, 36,37,38]. The success of these developments needs knowledge of prevalence of H.pylori.

In Ethiopia, the prevalence of H.pylori infection ranged from 7.7% [39] to 91% [40]. It is highly prevalent and recognized as major cause of gastrointestinal diseases. Studies conducted on the prevalence, risk factors and other clinical forms of H.pylori on different population and geographical areas are reporting conflicting results. Socioeconomic factors, sanitation, crowded living conditions, unsafe food and water, ethnicity as well as poverty can contribute to H.pylori infections [41]. Studies published on the prevalence of H.pylori in Ethiopia dated back to the 1990’s [42]. However, comprehensive review has not been done on its prevalence and associated factors in Ethiopia. Therefore; this study was done to estimate the pooled prevalence of H.pylori infection and associated factors in Ethiopia.

Methods

Data bases and search strategy

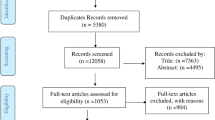

PubMed, Embase, and Google scholar were searched to identify potential articles on H.pylori infections in Ethiopia. To include unpublished studies, Ethiopian University repositories were searched and reference lists of eligible studies were searched to maximize inclusion of relevant studies. The search was conducted following the PRISMA guideline and checklists ( [43], Fig. 1). The following terms with MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) and Boolean operators were used to search PubMed; Helicobacter pylori OR H.pylori OR Campylobacter pylori OR C.pylori OR gastritis OR gastric cancer OR gastric carcinoma OR peptic ulcer disease OR PUD OR duodenal ulcer OR dyspepsia OR mucosa associated lymphoid tissue OR MALT AND Ethiopia. The search was limited to English language publications and done independently by each reviewer to minimize bias and the missing of studies. Search results were combined in to EndNote X6 file (Clarivate Analytics USA) and duplicates were removed. All articles published up to June 30, 2018 were included in the review if fulfilled the eligibility criteria (Table 1).

Quality assessment

The quality of included studies was assessed by using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) (Additional file 1). Two authors independently assessed the quality of each study. Disagreements between authors was resolved by discussion and articles were included if agreement was reached between the authors.

Data extraction

Data were extracted into customized Microsoft Excel. Data extracted from each included study include; author, publication year, study area, study period, study design, study population, sample size, laboratory tests used, prevalence and/or number of H.pylori cases. We have also contacted corresponding authors of the included studies for missing data though no one responded.

Data analysis

Studies providing data on crude prevalence of H.pylori or numbers of cases and study participants were included in the meta-analysis. Prevalence for individual studies was determined by multiplying the ratio of cases to sample size by 100. The estimation of pooled prevalence and summary odds ratios of H.pylori infection was done using CMA 2.0 and RevMan 5.3 softwares. Subgroup analyses were done by study period, study region, study design, laboratory tests used (types and numbers) and publication history. With the assumption that true effect sizes exists between eligible studies, the random effects model was used to determine the pooled prevalence, summary odds ratios and 95% CIs. Significant association between H.pylori infections and potential factors was declared at p-value < 0.05. Heterogeneity was evaluated using the Cochran’s Q test and I2 statistics. Significant heterogeneity was declared at I2 > 50% and Q-test (P < 0.10).

Publication bias and sensitivity analysis

Funnel plots were drawn to assess the possibility of publication bias. We plotted the studies’ logit event rate and the standard error to detect asymmetry in the distribution. A gap in the funnel plot indicates potential for publication bias. In addition, Begg’s adjusted rank correlation and Egger’s regression asymmetry tests were used to assess publication bias, with P < 0.05 considered to indicate potential publication bias. Sensitivity analysis, leave-one-out analysis was done to assess the prime determinant of the pooled prevalence of H.pylori infection and to detect the possible causes of heterogeneity between studies.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

Thirty seven studies with a total population of 18,890 met the inclusion criteria and included in the analysis. The detail characteristics of included studies are shown in (Table 2). The included studies were conducted between 1990 and 2017; of which 29 were published and 8 were unpublished. Thirteen studies were conducted in the Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Region (SNNPR) of Ethiopia. Eleven studies were conducted in Addis Ababa; nine studies in Amhara region, two studies in Oromia, one study in Somalia and one study in Benishangul Gumuz region. Nineteen studies were reported among adults [15, 39, 40, 42, 44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58], eight of the studies were reported on children [14, 59,60,61,62,63,64,65] while nine studies were conducted on both adults and children [25, 26, 58, 66,67,68,69,70,71,72]. One study did not describe the study population [73]. Among the include studies, 20 were cross-sectional, eight were case control, six were cohort, and two were retrospective studies. Ten studies used multiple tests in detecting H.pylori while 27 studies employed a single test to declare H.pylori infection. The prevalence of H.pylori from eligible individual studies ranged from 7.7 to 91.0%.

Pooled prevalence of H.pylori

A total of 18,890 Ethiopians were participated in the study; out of which 8979 were infected with H.pylori in the period under review giving an overall pooled prevalence of 52.2% (95% CI: 45.8–58.6; I2 = 51.05%, p = 0.503) (Fig. 2). Sensitivity analysis revealed no significant difference both in the pooled prevalence and heterogeneity. When one study was excluded from the analysis step-by-step, the pooled prevalence was between 50.5 and 53.5% while heterogeneity was similar (I2 = 53.5%). Drawing of funnel plot supported with Egger’s regression (p = 0.172) and Begg’s correlation (p = 0.367) tests showed no evidence of significant publication bias (Fig. 3).

Subgroup prevalence of H.pylori

Prevalence of H.pylori for subgroups was analyzed for study region, study period, sample size, study design, type and number of diagnostic tests used and publication history. The prevalence of H.pylori when studies were categorized by region ranged from 39.9% (95% CI: 17.3–67.7%; I2 = 67.6%, P = 0.486) in Oromia to 71% (95% CI: 32.5–92.6.2; I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.280) in Somalia. Other regional prevalence rates were 48.1% in Addis Ababa, 54.6% in Amhara, 48.7% in Benishangul Gumuz and 53.6% in SNNPR. Subgroup analysis by publication history showed a prevalence of 56.5% from published and 36.8% from unpublished studies. Subgroup analysis was also computed by the study period when the studies were conducted to see the trend of H.pylori infection. Hence, the prevalence of H.pylori was 64.4% in the period 1990–2000, 62.2% in the period 2001–2011 and 42.9% in the period 2012–2017, showing a decreasing trend. The pooled prevalence was also higher in studies which used multiple tests than studies employed a single test to detect H.pylori infection (62.9 and 48.1%, respectively) (Table 3).

Factors associated with H.pylori infection

Factors associated with H.pylori infections were grouped in to; sociodemographic, environmental, behavioral and clinical factors. Summary odds ratios (ORs) and their respective 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed based on the random effects model. Whenever there was data from the studies, we have tried to summarize the ORs and 95% CIs to identify the factors associated with H.pylori infections.

Socio-demographic risk factors

Available sociodemographic data (by age, sex, residency and level of education) were extracted and analyzed to determine their possible association with H.pylori infection but none of these variables had significant association. Even though not significant; male participants (OR = 1.07; 95% CI: 0.93–1.23; p = 0.33) and urban residents (OR = 1.04; 95% CI: 0.74–1.74; p = 0.83) were more likely to be infected with H.pylori than their counter parts (Fig. 4).

Environmental factors

Sources of drinking water, hand washing before meal and after toilet were the environmental factors assessed for their possible association with H.pylori infection. Participants who were not washing their hands after toilet were more likely to be infected with H.pylori (OR = 1.8; 95% CI: 1.19–2.72; p = 0.005). Other variables had no significant association (Fig. 5).

Behavioral factors

Chat chewing, cigarette smoking and drinking alcohol were analyzed for any association with H.pylori infection. Even though not significant, chat chewing had a preventive effect (OR = 0.94; 95% CI: 0.58–1.53; p = 0.80) for H.pylori infection while smoking increases the risks of infection (OR = 1.25; 95% CI: 0.67–2.30; p = 0.48). Participants who were taking alcohol had a significant association with H.pylori infection (OR = 1.34; 95% CI: 1.03–1.74; p = 0.03) (Fig. 6).

Clinical factors

Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, allergic reactions, hyperemesis gravidarum, HIV and TB infections were some of the clinical factors reported with H.pylori infection by included studies. Because studies on allergic reactions, hyperemesis gravidarum, HIV and TB infections are small enough to compute pooled summary of odds ratios, we analyzed only the association between GI symptoms and H.pylori infection. Hence; participants who had GI symptoms (including dyspepsia, gastritis, peptic ulcer and related) were more likely to be infected with H.pylori (OR = 2.23; 95% CI: 1.59–3.14; p < 0.00001) (Fig. 7).

Meta-regression

Meta-regression was done to explore the trend of prevalence of H.pylori by year of study and sample size of the included studies. A significant downward trend of H.pylori infection was observed from 1990 to 2017 (B = − 0.067, p = 0.00004). However; there was no significant association between prevalence of H.pylori and sample size of the studies even though there was a slight decrease of prevalence of H.pylori with increased sample size (B = − 0.00079; p = 0.193) (Fig. 8).

Discussion

The global prevalence of H.pylori infection was estimated at 48.5% in 2017 [6]. The World Gastroenterology Organization (WGO) in its 2011 global guideline reported prevalence of > 95% among adults, 48% among 2–4 age groups and 80% among children aged at six in Ethiopia [1] but there was no national pooled prevalence reported yet. Estimating the national and regional prevalence, trends of infection and associated factors is crucial to establish appropriate strategies for the diagnosis, prevention and control of H.pylori infection. Estimates of H.pylori infection is usually challenging since some factors have profound effect than others and some studies look in to distinct population or samples, method of isolation, geographical distribution, socioeconomic, behavioral, environmental and clinical factors.

The 37 studies included in our analysis determined the prevalence of antigens and/or antibodies (either IgM, IgA or IgG) of H.pylori and ranged from 7.7 to 91.0% among different study populations, geographical areas and study period. However, the overall pooled prevalence of H.pylori in Ethiopia was estimated to be 52.2% (95% CI: 45.8–58.6). This overall prevalence estimate is lower than reports from Nigeria (87.7%), South Africa (77.6%), Portugal (86.4%), Tunisia (72.8%), Brazil (71.2%) and Estonia (82.5%) [6]. Some reasons may explain the lower prevalence in Ethiopia. Firstly; the number of studies and participants included; pooled from 37 studies and 18,890 participants in our analysis compared to fewer number of studies and participants. Second, our analysis included recent reports which showed a decreasing trend to recent times. Third, most of the laboratory tests used by studies included in our review were based on stool antigen for detection of H.pylori; which has low isolation rate.

However, our estimate is higher than other countries; 22.1% in Denmark, 43.6% in Thailand, 46.8% in Democratic republic of Congo (DRC) and 40.9% in Egypt [6]. These differences might be attributable to differences in time trend of studies, poor personal and environmental hygiene, low socioeconomic status and behavioral factors; and sensitivity/specificity of laboratory tests employed in detecting H.pylori. Stool antigen and serological tests were the most widely used methods used in detecting H.pylori infection.

The trend of H.pylori infection showed a decreasing pattern in the last three decades from 1990 to 2017; 64.4% in the first decade (1990–2000), 62.2% in the second decade (2001–2011) and 42.9% in the third decade (2012–2017). This decrement might be related with relative improvements in sanitation, water access, life style and behavioral changes, quality of life and socioeconomic status, and increased awareness on the transmission, diagnosis, eradication therapy, prevention and control of H.pylori infection.

Regional estimates of H.pylori infection in the subgroup analysis showed a lower prevalence of 39.9% in Oromia and higher prevalence of 71.0% in Somalia region. This regional difference can be attributable that in Somalia, study participants were University students with known gastritis which is a known risk factor for H.pylori infection. Other explanations could be related with sociodemographic, socioeconomic, environmental, clinical, behavioral factors and number of studies included in each category.

The prevalence of H.pylori infection differs on the bases of laboratory tests used. Higher prevalence was observed when detection is supplemented with sensitive tests including PCR, culture, rapid urease test and histopathology as shown in (Table 3). This is supported by studies comparing diagnostic tests for H.pylori that sensitive tests improve the detection rate of H.pylori infections from clinical samples [74,75,76,77]. In addition, combination of at least two diagnostic methods is recommended to increase the validity of results [16, 20, 28, 48, 63, 78,79,80,81,82], but only ten studies used multiple tests to make a definitive diagnosis of H.pylori in our analysis. Our subgroup analysis confirms that the pooled prevalence of H.pylori infection when multiple tests are used is higher than the pooled prevalence when a single test is used to detect H.pylori infection (62.9% Vs 48.1%).

Several risk factors for H.pylori infection were identified and reported usually with conflicting result. These factors are to be analyzed and pooled to have a summary of effect sizes. The results of this meta-analysis showed that participants with gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms were more likely to be infected with H.pylori (OR = 2.23; 95% CI: 1.59–3.14). This could be due to the effect of GI symptoms providing a growing medium (changing pH, thinning of gastric wall, gastric ulceration, change in gut microbiota) for the bacteria.

Although the type and level of alcohol, amount and frequency of consumption were not described, individuals taking alcohol were more likely to be infected with H.pylori infection than those who did not consume alcohol. This result is inconsistent with previous studies [83,84,85,86] reporting that alcohol consumption has either a protective effect or has no any relation with H.pylori infection. Other study [87] reported alcohol as a risk factor for H.pylori supporting our analysis. As alcohol is known to directly damage the gastric mucosal layer, it is theoretically possible that alcohol can provide ways for H.pylori infection. In addition, heavy drinking can possibly predispose consumers to social contacts that favor transmission of H.pylori infection. Other mechanism may be involved in the synergistic effect of alcohol including bacterial adherence and host factors in facilitating infection among drinkers. Further longitudinal and epidemiological studies are needed to test these explanations.

Previous studies [1, 86, 88] have reported that the prevalence of H.pylori infection seems to increase with age but the increment with age is assumed most likely due to cohort effect. As most infections are acquired early in life; the bacteria usually persists indefinitely unless treated with specific antibiotic. In our analysis, consistent with the assumption, participants in the age of <20 years were less likely to be infected when compared to above 20 years of age but the association is not significant (OR = 0.85; 95% CI: 0.70–1.03).

Poor sanitation and unsafe food and water were repeatedly reported as risk factors contributing for H.pylori infection. In our analysis, individuals who were not washing their hands after toiled were more likely to be infected with H.pylori. This is in agreement with previous studies [1, 41] and can be explained that H.pylori is largely transmitted through feco-oral or oral-oral routes. Lack of proper sanitation and basic hygiene after toilet, therefore; can be source of infection and increase the chance of acquiring H.pylori. World Health Organization (WHO) has also identified it as one of the greatest risks for human health and categorized it as a high priority pathogen for research and development of new and effective treatments [35].

In the meta-regression analysis, the prevalence of H.pylori infection showed a significant downward trend from 1990 to 2017 (B = − 0.067, p = 0.00004). This can be due to relative improvements in sanitation, water access, lifestyle and behavioral changes, quality of life and socioeconomic status, increased awareness on the transmission, diagnosis, eradication therapy, preventive and control of H.pylori infection. On the other hand; a slight decrement of prevalence of H.pylori was observed with increased sample size (B = − 0.00079; p = 0.193) but the association was not significant. This might be related with the numbers of studies done on large sample sizes in that only few studies were done when compared to numbers of studies done on small sample sizes.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this study is that it included relatively larger numbers of published and unpublished studies without time limit of publication year. It has provided the national pooled prevalence, trends of infection and identified factors associated with H.pylori infection. The study included sub-group analysis and meta-regression of differences of study area, laboratory tests, study period, sample size and study designs. In few regions of Ethiopia, no study was found from and most identified studies were hospital based which could affect the generalisability of our findings. Moreover, there was lack of data sets to investigate the association between H.pylori infection and possible risk factors and the outcome variables may be affected by other cofounders.

Conclusion

The prevalence of H.pylori infection remains high; more than half of Ethiopians were infected and significant association was observed between H.pylori infection and absence of hand washing after toilet, alcohol drinking and presence of gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms. These findings strengthen the action to implement the control and prevention of H.pylori infection more effectively to prevent gastric cancer and other related complications in Ethiopia. Although the trend of infection showed a decreasing pattern; appropriate use of eradication therapy, health education primarily to improve knowledge and awareness on the transmission dynamics of the bacteria, behavioral changes, adequate sanitation, population screening and diagnosis using multiple tests are required to reduce H.pylori infections.. Recognizing the bacteria as a priority issue and designing gastric cancer screening policies are also recommended.

Abbreviations

- EIA:

-

Enzyme immune assay

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay

- GI:

-

Gastrointestinal

- H.pylori:

-

Helicobacter pylori

- MALT:

-

Mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue

- NUD:

-

Non-ulcer dyspepsia

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- RUT:

-

Rapid urease test

- UBT:

-

Urea breath test

- WGO:

-

World Gastroenterology organization

- WHO:

-

World health organization

References

Hunt RH, Xiao SD, Megraud F, et al. Helicobacter pylori in developing countries, world gastroenterology organisation global guideline. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2011;20(3):299–304.

GO MF. Review article: natural history and epidemiology of helicobacter pyloriinfection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16(Suppl. 1):3–15.

Zabala Torrres B, Lucero Y, Lagomarcino AJ, et al. Prevalence and dynamics of Helicobacter pylori infection during childhood. Helicobacter. 2017;22:e12399.

O’Connor A, O’Morain CA, Ford AC. Population screening and treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:230–40.

Jemilohun AC, Otegbayo JA, Ola SO, et al. Prevalence of helicobacter pylori among Nigerian patients with dyspepsia in Ibadan. Pan Afr Med J. 2011;6:18.

James KY, WYL H, Ng WK, et al. Global prevalence of helicobacter pylori infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:420–9.

Salih BA. Helicobacter pylori infection in developing countries: the burden for how long? Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(3):201–7.

Lindkvist PA, D. Nilsson, et al. age at acquisition of helicobacter pylori infection: comparison of a high and a low prevalence country. Scand J Infect Dis. 1996;28(2):181–4 PubMed PMID: 8792487. Epub 1996/01/01. eng.

Miele ERE. Helicobacter pylori Infection in Pediatrics. Helicobacter. 2015;20(Suppl. S1):47–53.

Matjazˇ Homan IH, Kolacˇek S. Helicobacter pylori in pediatrics. Helicobacter. 2012;17(Suppl.1):43–8.

Ng QX, Venkatanarayanan N, De Deyn MLZQ, et al. A meta-analysis of the association between Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection and hyperemesis gravidarum. Helicobacter. 2017;23:e12455.

Iraj Nabipour KV, Jafari SM, et al. The association of metabolic syndrome and Chlamydia pneumoniae, Helicobacter pylori, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex virus type 1: The Persian Gulf Healthy Heart Study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2006;5:25.

Michael A, Mendall PMG, Molineaux N, et al. Relation of Helicobacter pyloi infection and coronary heart disease. Br Heart J. 1994;71:437–9.

Taye B, Enquselassie F, Tsegaye A, et al. Effect of early and current helicobacter pylori infection on the risk of anaemia in 6.5-year-old Ethiopian children. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:270 PubMed PMID: 26168784. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC4501201. Epub 2015/07/15. eng.

Kibru D, Gelaw B, Alemu A, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and its association with anemia among adult dyspeptic patients attending Butajira Hospital, Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:656 PubMed PMID: 25487159. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4264248.

Ali MAH, Muhammad EM, Hameed BH, et al. The impact of Helicobacter pylori infection on iron deficiency anemia in pregnancy. Iraqi J Hematol. 2017;6(2):60.

Lauren Hudak AJ, Haj S, et al. An updated systematic review and meta- analysis on the association between Helicobacter pyloriinfection and iron deficiency anemia. Helicobacter. 2017;22:e12330.

Alshareef SA, Rayis DA, Adam I, et al. Helicobacter pyloriinfection, gestational diabetes mellitus and insulin resistance among pregnant Sudanese women. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11:517.

Jeon CY, Haan MN, Cheng C, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection is associated with an increased rate of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:520–5.

Tseng C-H. Diabetes, insulin use and Helicobacter pylori eradication: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:46.

Abdulbari Bener RM, Afifi M, et al. Association between type 2 diabetes mellitus and helicobacter pylori infection. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2017;18(4):225–9.

Mengge Zhou JL, Qi Y, et al. Association between Helicobacter pylori infection and risk of new-onset diabetes: a community-based, prospective cohort study. Lancet Endocrinol. 2016;14. www.thelancet.com/diabetes-endocrinology.

Mohammadreza Motie AR, Abbasi H, et al. The Relationship Between Cholecystitis and Presence of Helicobacter pylori in the Gallbladder. Zahedan J Res Med Sci. 2017;19(7):e9621.

Li Cen JP, Zhou B, et al. Helicobacter Pyloriinfection of the gallbladder and the risk of chronic cholecystitis and cholelithiasis: A systematic review and meta- analysis. Helicobacter. 2018;23:e12457.

Moges F, Kassu A, Mengistu G, et al. Seroprevalence of helicobacter pylori in dyspeptic patients and its relationship with HIV infection, ABO blood groups and life style in a university hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(12):1957–61 PubMed PMID: 16610007. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4087526.

Getachew Seid KD, Tsegaye A. Helicobacter pylori infection among dyspeptic and non-dyspeptic HIV patients at YekaHealth center, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 2017.

Sarfo FS, Eberhardt KA, Dompreh A, et al. Helicobacter pylori Infection is associated with higher CD4 T cell counts and lower HIV-1 viral loads in ART-Naïve HIV-positive patients in Ghana. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0143388.

Taye B, Enquselassie F, Tsegaye A, et al. Effect of helicobacter pylori infection on growth trajectories in young Ethiopian children: a longitudinal study. Int J Infect Dis. 2016;50:57–66 PubMed PMID: 27531186. Epub 2016/08/18. eng.

Shen X, Yang H, Wu Y, Zhang D, Jiang H. Meta-analysis: Association of Helicobacter pylori infection with Parkinson’s diseases. Helicobacter. 2017;22:e12398.

Mégraud F. Time to change approaches to helicobacter pylori management. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:692–3.

Seck A, Burucoa C, Dia D, et al. Primary antibiotic resistance and associated mechanisms in Helicobacter pylori isolates from Senegalese patients. Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials. 2013;12:3.

Vakil N, Vaira D. Treatment for H. pylori infection: new challenges with antimicrobial resistance. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47(5):383–8.

Jaka H, Rhee JA, Östlundh L, et al. The magnitude of antibiotic resistance to Helicobacter pylori in Africa and identified mutations which confer resistance to antibiotics: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2018;18:193.

Ferenc S, Gnus J, Kościelna M, et al. High antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori and its effect on tailored and empiric eradication of the organism in Lower Silesia, Poland. Helicobacter. 2017;22:e12365.

Dang BN, Graham DY. Helicobacter pylori infection and antibiotic resistance: a WHO high priority. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14(1):383–4.

Asrat D, Kassa E, Mengistu Y, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of helicobacter pylori strains isolated from adult dyspeptic patients in Tikur Anbassa University Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2004;42(2):79–85 PubMed PMID: 16895024.

Ben Mansour K, Burucoa C, Zribi M, et al. Primary resistance to clarithromycin, metronidazole and amoxicillin of Helicobacter pylori isolated from Tunisian patients with peptic ulcers and gastritis: a prospective multicentre study. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2010;9:22.

Kuo Y-T, Liou JM, El-Omar EM, et al. Primary antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori in the Asia-Pacific region: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:707–15.

Ayele B, Molla E. Dyspepsia and Associated Risk Factors at Yirga Cheffe Primary Hospital, Southern Ethiopia. Clin Microbiol. 2017;6:3.

Asrat D, Nilsson I, Mengistu Y, et al. Prevalence of helicobacter pylori infection among adult dyspeptic patients in Ethiopia. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2004;98(2):181–9 PubMed PMID: 15035728.

Natuzzi E. Neglected tropical diseases: is it time to add helicobacter pylorito the list? Glob Health Promot. 2013;20(3):47–8.

Tedla Z. Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with upper gastrointestinal symptoms in Arba Minch hospital: southwestern Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 1992;30(1):43–9 PubMed PMID: 1563364.

LA Moher D, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(6):e1000097.

Yilikal Assefa KD. Association of Helicobacter pylori infection and hyperemesis gravidarum women: a case control study in selected Hospital and two health centers in Kirkos Sub-city, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 2017.

Kebede W, Mathewos B, Abebe G. H. PyloriPrevalence and its effect on CD4+Lymphocyte count in active pulmonary tuberculosis patients at hospitals in Jimma, Southwest Ethiopia. Int J Immunol. 2015;3(1):7–13.

Tadege T, Mengistu Y, Desta K, Asrat D. Serioprevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection in and its Relationship with ABO Blood Groups. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2015;9(1):55–9.

Tebelay Dilnessa MA. Prevalence of helicobacter pylori and risk factors among dyspepsia and non-dyspepsia adults at Assosa general hospital, West Ethiopia: a comparative study. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2017;31(1):4–12.

Tadesse E, Daka D, Yemane D, Shimelis T. Seroprevalence of helicobacter pylori infection and its related risk factors in symptomatic patients in southern Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:834 PubMed PMID: 25421746. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4255656.

Taddesse G, Habteselassie A, Desta K, et al. Association of dyspepsia symptoms and helicobacter pylori infections in private higher clinic, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2011;49(2):109–16 PubMed PMID: 21796910.

Seid A, Tamir Z, Kasanew B, Senbetay M. Co-infection of intestinal parasites and helicobacter pylori among upper gastrointestinal symptomatic adult patients attending Mekanesalem hospital, Northeast Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):144 PubMed PMID: 29463293. Pubmed Central PMCID: 5819640.

Seid A, Tamir Z, Demsiss W. Uninvestigated dyspepsia and associated factors of patients with gastrointestinal disorders in Dessie referral hospital, Northeast Ethiopia. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18(1):13 PubMed PMID: 29347978. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC5774098. Epub 2018/01/20. eng.

Kumera Terfa KD. Prevalence of helicobacter pylori infections and associated risk factors among women of child bearing ages in selected health centers, Kolfe Keranio sub city, Addis Ababa; 2015.

Kassu Desta DA, Derbie F. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among health blood donors in Addis Ababa Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2002;12:2.

Hailu G. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Helicobacter pylori among Adults at Jinka Zonal Hospital, Debub Omo Zone, Southwest Ethiopia. Autoimmune Infect Dis. 2016;2:2.

Getachew Alebie DK. Prevalence of Helicobacter PyloriInfection and Associated Factors among Gastritis Students in Jigjiga University, Jigjiga, Somali Regional State of Ethiopia. J Bacteriol Mycol. 2016;3:3.

Eden Ababu KD, Hailu M. H.Pyloriinfection and its association with CD4 T cell count among HIV infected individuals who attended the ART service in kotebe health center, Yeka subcity, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 2017.

Misganaw Birhaneselassie AA. The relationship between dyspepsia and H. pylori infection in Southern Ethiopia Global Advanced Research. J Med Med Sci. 2017;6(5):086–90.

Alemayehu A. Seroprevalence of helicobacter pylori infection and its risk factors among adult patients with dyspepsia in Hawassa teaching and referral hospital, south Ethiopia; 2011.

Lindkvist P, Enquselassie F, Asrat D, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection in Ethiopian children: a cohort study. Scand J Infect Dis. 1999;31(5):475–80 PubMed PMID: 10576126. Epub 1999/11/27. eng.

Lindkvist P, Enquselassie F, Asrat D, et al. Risk factors for infection with helicobacter pylori - a study of children in rural Ethiopia. Scand J Infect Dis. 1998;30(4):371–6 PubMed PMID: 9817517.

Amberbir A, Medhin G, Erku W, et al. Effects of helicobacter pylori, geohelminth infection and selected commensal bacteria on the risk of allergic disease and sensitization in 3-year-old Ethiopian children. Clin Exp Allergy. 2011;41(10):1422–30 PubMed PMID: 21831135. Epub 2011/08/13. eng.

Amberbir A, Medhin G, Abegaz W, et al. Exposure to helicobacter pylori infection in early childhood and the risk of allergic disease and atopic sensitization: a longitudinal birth cohort study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2014;44(4):563–71 PubMed PMID: 24528371. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC4164268. Epub 2014/02/18. eng.

Gobena MT. Association of Helicobacter pylori infection with atopy and allergic disorders in Ziway, Central Ethiopia; 2017.

Ahmed Kemal GM. Prevalence of H.pylori infection in pediatric patients who is clinically diagnosed for gastroenteritis in Beham specialized children’s higher clinic, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 2014.

Abebe Worku KD, Wolde M. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori and intestinal parasite and their associated risk factors among school children at Selam Fire Elementary School in Akaki Kality, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 2017.

Workineh M, Andargie D. A 5-year trend of helicobacter pylori seroprevalence among dyspeptic patients at Bahir Dar Felege Hiwot referral hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Res Rep Trop Med. 2016;7:17–22 PubMed PMID: 30050336. Pubmed Central PMCID: 6028059.

Seid A, Demsiss W. Feco-prevalence and risk factors of helicobacter pylori infection among symptomatic patients at Dessie referral hospital, Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2018b;18(1):260 PubMed PMID: 29879914. Pubmed Central PMCID: 5991442.

Mathewos B, Moges B, Dagnew M. Seroprevalence and trend of Helicobacter pylori infection in Gondar University Hospital among dyspeptic patients, Gondar, North West Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:346 PubMed PMID: 24229376. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3765695.

Kasew D, Abebe A, Munea U, et al. Magnitude of helicobacter pylori among dyspeptic patients attending at University of Gondar Hospital, Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2017;27(6):571–80 PubMed PMID: 29487466. Pubmed Central PMCID: 5811936.

Henriksen TH, Nysaeter G, Madebo T, et al. Peptic ulcer disease in South Ethiopia is strongly associated with helicobacter pylori. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1999;93(2):171–3 PubMed PMID: 10450442.

Teka B, Gebre-Selassie S, Abebe T. Sero-prevalence of helicobacter Pylori in HIV positive patients and HIV negative controls in St. Paul’s general specialized hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Sci J Public Health. 2016;4(5):387–93.

Abebaw W, Kibret M, Abera B. Prevalence and risk factors of H. pylori from dyspeptic patients in northwest Ethiopia: a hospital based cross-sectional study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(11):4459–63.

Tsega E, Gebre W, Manley P, Asfaw T. Helicobacter pylori, gastritis and non-ulcer dyspepsia in Ethiopian patients. Ethiop Med J. 1996;34(2):65–71 PubMed PMID: 8840608. Epub 1996/04/01. eng.

Daniel Asrat EK, Mengistu Y, et al. Comparison of Diagnostic Methods for Detection of Helicobacter pyloriInfection in Different Clinical Samples of Ethiopian Dyspeptic Patients. Asian J Cancer. 2007;6:4.

Fatemeh Khadangi MY, Kerachian MA. Review: Diagnostic accuracy of PCR-based detection tests for Helicobacter Pylori in stool samples. Helicobacter. 2017;22:e12444.

Calvet X, Sánchez-Delgado J, Montserrat A, et al. Accuracy of Diagnostic Tests for Helicobacter pylori: A Reappraisal. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1385–91.

Ante Tonkic MT, Lehours P, Mégraud F. Epidemiology and diagnosis of helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2012;17:1–8.

Chen Y, Segers S, Blaser MJ. Association between Helicobacter pylori and mortality in the NHANES III study. MJ Gut. 2013;62:1262–9.

Megraud F, Gisbert JP. Towards effective empirical treatment for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Lancet. 2016;388:2325–6.

Macías-García F, Llovo-Taboada J, Díaz-López M, et al. High primary antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter Pylori strains isolated from dyspeptic patients: A prevalence cross-sectional study in Spain. Helicobacter. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1111/hel.12440.

Shanks AM, El-Omar EM. Helicobacter pylori infection, host genetics and gastric cancer. J Dig Dis. 2009;10:157–64.

Manfred Stolte AM. Helicobacter pyloriand gastric Cancer. Oncologist. 1998;3:124–8.

Nikanne JH. Effect of alcohol consumption on the risk of helicobacter pylori infection. Digestion. 1991;50:92–8.

Hermann Brenner GB, Lappus N, et al. Alcohol consumption and helicobacter pylori infection: results from the German National Health and nutrition survey. Epidemiology. 1999;10(3):214–8.

Atsushi Ogihara SK, Hasegawa A, et al. Relationship between helicobacter pylori infection and smoking and drinking habits. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:271–6.

Mark Woodward CM, McColl K. An investigation into factors associated with Helicobacter pylori infection. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:175–81.

Li Zhang GDE, Harry H, et al. Relationship between alcohol consumption and active helicobacter pylori infection. Alcohol Alcohol. 2010;45(1):89–94.

Eusebi LH, Zagari RM, Bazzoli F. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2014;19(Suppl. 1):1–5.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The authors declare that they did not receive funding for this research from any source.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed are included in the results of the manuscript and its supplementary files.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AM: Conceived and designed the study; analyzed data, and drafted the manuscript. AM, CG, BZ, and TA select and assess quality of studies, extract data, interpret result, and review the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for cross sectional studies. (DOC 34 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Melese, A., Genet, C., Zeleke, B. et al. Helicobacter pylori infections in Ethiopia; prevalence and associated factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol 19, 8 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-018-0927-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-018-0927-3