Abstract

Background

The Portuguese National Health System (NHS) provides universal coverage and near-free health care, but the population has high out-of-pocket expenses and unmet care needs. This suggests impaired accessibility, a key dimension of primary care. The COVID-19 pandemic has further affected access to health care. Understanding General Practitioners’ (GP) experiences during the pandemic is necessary to reconfigure post-pandemic service delivery and to plan for future emergencies. This study aimed to assess accessibility to GPs, from their perspective, evaluating determinants of accessibility during the second pandemic year in Portugal.

Methods

All GPs working in NHS Family Practices in continental Portugal were invited to participate in a survey in 2021. A structured online self-administered anonymous questionnaire was used. Accessibility was assessed through waiting times for consultations and remote contacts and provision of remote access. NHS standards were used to assess waiting times. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the study sample. Associations between categorical variables were tested using the χ2 statistic and the Student t-test was used to compare means of continuous variables.

Results

A total of 420 GPs were included (7% of the target population). Median weekly working hours was 49.0 h (interquartile range 42.0–56.8), although only 14% reported a contracted weekly schedule over 40 h. Access to in-person consultations and remote contacts was reported by most GPs to occur within NHS time standards. Younger GPs more often reported waiting times over these standards. Most GPs considered that they do not have enough time for non-urgent consultations or for remote contacts with patients.

Conclusions

Most GPs reported compliance with standards for waiting times for most in-person consultations and remote contacts, but they do so at the expense of work overload. A persistent excess of regular and unpaid working hours by GPs needs confirmation. If unpaid overtime is necessary to meet the regular demands of work, then workload and specific allocated tasks warrant review. Future research should focus on younger GPs, as they seem vulnerable to restricted accessibility. GPs’ preferences for more in-person care than was feasible during the pandemic must be considered when planning for the post-pandemic reconfiguration of service delivery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In primary care-based health systems, General Practitioners (GPs) are a common point of entry to the system for patients when a new health problem arises [1]. The availability of GPs has been found to correlate with better population health [2]. Thus, accessibility to GPs is a key feature of primary care-based systems [3]. The COVID-19 pandemic has affected access to health care. Staff was reduced due to infection and mandatory isolation [4, 5]. In-person consultations were restricted to prevent virus spread and telehealth was boosted [4, 6]. GPs were diverted to COVID-19-related work, further reducing accessibility in primary care [5].

The Portuguese health system is primary care-based, providing universal and mostly free coverage for health care (Table 1).

In spite of universal coverage and near-free health care, Portugal ranks high in the OECD table regarding greater per capita out-of-pocket expenses and catastrophic health care spending [12]. In the pandemic year of 2020, it was the second worst country regarding unmet care needs [12]. Impaired access to care in the public sector may explain why patients choose to pay for private care. Non-compliance with maximum waiting times for in-person GP care was reported even before the pandemic [13]. Also, patient satisfaction with telephone access to GPs was lower than overall satisfaction with care [14].

Early in the pandemic, Portuguese National Health Service (NHS) Family Practices were directed to cancel non-urgent care and institute triage systems. Respiratory hubs were used to assess patients presenting with symptoms suggestive of COVID-19 [15]. Patients suspected as COVID-19 cases were entered into a national database [16]. Most infected patients were sent home to isolate and assigned to daily remote follow-up by their GP [17]. Thus, during the pandemic years of 2020 and 2021 and into early 2022, GPs were diverted from their work in Family Practices to the telephone follow-up of infected patients or to cover shifts in respiratory assessment hubs. From 2021 on, they were also assigned to work in vaccination centres. As a result, there was a substantial and sustained drop in in-person consultations with GPs [12].

Understanding how GPs have experienced accessibility during the pandemic is necessary to reconfigure post-pandemic service delivery and to plan for future health emergencies. This study aimed to assess accessibility to GPs in Portugal, including in-person and remote access, to describe available resources and the views and experiences of GPs, and to evaluate determinants of accessibility during the second year of the pandemic.

Methods

This cross-sectional study used data from a survey of GPs working in NHS Family Practices in continental Portugal. It was part of a larger study on access to GPs which also included a patient survey. On 13/05/2021, the Portuguese Medical Board sent an e-mail to all registered GPs, inviting them to answer a structured online self-administered anonymous questionnaire. It used LimeSurvey software and required about 12 min to complete. The Medical Board files include the estimated target population of 5684 GPs working in the public sector in Portugal in May 2021 [18], as well as retired GPs and those working only in the private sector. Exclusion criteria were applied with 3 qualifier questions: retirement or leave for over 6 months, doctors not doing any work in NHS Family Practices in continental Portugal, or those without a patient list. A reminder was sent on 04/08/2021 and valid replies were accepted if received by 31/08/2021.

The questionnaire was constructed by the investigators, after a literature search for comparable studies and adaptation of relevant questions from retrieved questionnaires [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Four GPs and one statistician discussed the face and content validity of the questionnaire. A pilot study on a convenience sample of final year Family Medicine residents also informed the final version of the questionnaire (Supplementary file 1). The areas covered included: actual working hours (excluding paid overtime); allocation of time for in-person care (office and home visits), remote contacts (telephone consultations, patient e-mails, video consultations, renewals of prescriptions and medical reports), and non-clinical work (management, meetings, continuing medical education, student/resident training); and demographics, including contracted weekly schedule, list size and Family Practice organizational model. Accessibility to GPs was assessed querying about waiting times for in-person consultations and remote contacts, provision of remote access, verification of data entered by patients into their personal area on NHS internet portal, views on accessibility arrangements, and available physical resources. GPs were asked to respond regarding the 4 working weeks before receiving the questionnaire.

NHS standards for provision of service were used to assess waiting times [8]. In-person appointments with one’s GP should be provided on the same day they are requested by the patient for acute illness. Appointments for non-acute reasons were to be arranged within 15 working days. Requests for home visits were to be met within 24 h. Remote requests for renewals of prescriptions and for issuing medical reports were to be met within 3 working days (Table 2). Given that no time standards are set for remote review of test results, telephone calls or e-mail contacts, the researchers set a cut-off of 3 working days, in line with the standards for other remote contacts. Provision of remote access was classified as ‘restricted’ if reported to be made available for ‘some’, ‘a few’ or ‘none’ of the patients, and as ‘broad’ is available for either ‘all ‘ or ‘many’ patients.

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the study sample and compare participants to the population of GPs working in Portugal [10, 29, 30]. Associations between accessibility (waiting times and provision of remote access) and GPs’ demographic and professional characteristics were sought. Associations between categorical variables were tested using the χ2 statistic and the Student t-test was used to compare means of continuous variables. A sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess if answering the questionnaire in the first half of the study period (as opposed to the second half) influenced the main outcomes (weekly working hours and compliance with NHS standards for waiting times).

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Matosinhos Local Health Unit on 10/07/2020 (nr. 59/CE/JAS).

Results

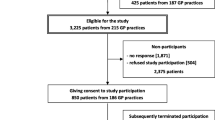

The Medical Board sent e-mail invitations to 8685 doctors to participate in the study, including the estimated population of 5684 GPs working in the public sector in Portugal in May 2021 [18]. There were 866 clicks on the link to the questionnaire. Exclusion criteria applied to 162 answers. Questionnaires without answers to items about consultations were also excluded (n = 284). A total of 420 participants were included, representing 7% of the estimated total population and 60% of those who opened the questionnaire and were eligible (Fig. 1).

Sample characterization

Most participants (68%) were female, their median age was 41 years (minimum 30, maximum 68, interquartile range 37–57 years). There were participants from each of the 55 Health Centres Groups across Portugal. Most GPs (42%) were from the Northern region. As for the organizational model of Family Practice, 46% of GPs worked in Model B, 33% in Model A and 21% in ‘UCSP’ clinics (Table 3). The average list size was 1726 patients (SD 241.4).

Compared to the general population of GPs in Portugal, participants were younger. The Centre region was overrepresented, while Lisbon and the Tagus Valley region and the Alentejo region were underrepresented. Model B Family Practices were overrepresented, while ‘UCSP’ type clinics were underrepresented (Table 3).

Working hours and tasks performed

Most GPs (68%) had a contracted workload in their NHS Family Practice between 36 and 40 h per week. While only 14% of GPs had a contracted weekly schedule over 40 h, most (80%) reported that, excluding paid overtime, they worked over 40 h a week in their NHS Family Practice (Table 4). Reported median weekly working hours was 49.0 h (interquartile range 42.0–56.8). The maximum weekly hours that could be reported on the survey form was 60, and this amount was reported by 74 participants (18%), but there were several comments at the end of the questionnaire stating that the weekly workload was over 60 h.

The largest share of the participants’ workload in NHS Family Practices was for non-urgent, in-person visits (19 h weekly, on average). The second and third largest were for remote clinical work, and for urgent in-person visits, excluding visits for acute respiratory complaints (Table 4). COVID-19 related work (work in vaccination centres, follow-up calls, and shifts in acute respiratory hubs) accounted for an average of 8 h weekly.

Among participant GPs, 77% played other nonclinical roles in their practices or health centres groups, most often (51%) as trainers of GP residents (Table 4). Paid work outside NHS Family Practices was reported by 31% of participants, most often in the private and social sector (25%) and, less often, in NHS hospitals and in universities.

Remote care

Most GPs reported that all the consultation rooms in NHS Family Practices had external landline telephone access (71%) and internet access (97%), but 74% stated that no video cameras were available. Nearly all GPs (99.5%) were provided with a work e-mail account and 58% had a work mobile phone.

Most GPs stated they provided their patients with access to discuss medical queries both by e-mail and through the practice telephone line, though not via their work or personal mobile phones, nor by video consultation (Table 5). Most GPs reported ‘never’ (54%) or ‘seldom’ (25%) consulting the information that patients entered on the NHS patient internet portal.

Accessibility to the General Practitioner

Access to in-person office consultations and remote contacts was reported by most GP to occur within maximum waiting times (MWT) or up to 3 working days where MWT were not defined (Table 6). Home visits were reported to exceed MWT by 93% of GPs, and remote review of test results, reported to exceed 3 working days by 51%. Regarding time in the waiting room, 85% of GPs stated their consultations usually began up to 15 min after the scheduled time.

Doctor’s views on accessibility arrangements

Most participant GPs consider that they do not have enough time for non-urgent consultations nor for remote contacts (especially for e-mails and telephone calls) (Table 7). Most GPs consider remote contacts (except for video consultations and data entry in the NHS portal) to be useful for patient management.

GPs were asked if they would change their use of telephone calls, e-mails, and video consultations in some situations (Table 8). If real time access to patient files was available, most GPs stated they would use e-mail and video consultations more often (64% and 50%, respectively). If it was included in their performance assessment, most GPs (52%) stated they would use e-mail more often.

Provision of telephone and e-mail access and GP characteristics

Younger GPs more often reported restricted telephone and e-mail access (Table 9). GPs from the Centre region more often reported restricted access to patients through the practice telephone line and mobile telephones provided at work. GPs working in the ‘UCSP’ model of Family Practices most often reported restricted access to the discussion of medical queries by e-mail, followed by those working in model A Family Practices. GPs working only in NHS Family Practices more often reported restricted access through their personal mobile phone. GPs working more hours more often reported broad access to discuss medical queries by e-mail.

Waiting times and GP characteristics

The age of the GP was associated with waiting times. Younger participants more often reported waiting times over MWT for non-urgent consultations and for all types of remote contacts (or over 3 working days where MWT were not defined) (Table 10). GPs working in the North region, followed by those from the Centre region, more often reported waiting times over MWT for non-urgent consultations. GPs working in the Centre more often reported waiting times over 3 working days for remote medical reports, telephone, and e-mail contacts. GPs working in practices on a salary-only scheme (‘UCSP’), followed by GPs working in model A Family Practices, more often reported waiting times over MWT for non-urgent consultations. The only factor associated with longer waiting times for urgent consultations was the contracted weekly workload. GPs with less contracted hours more often reported waiting times over MWT. GPs with smaller lists more often reported waiting times over MWT for requests for remote medical reports and for review of test results. Total weekly hours worked were not associated with waiting times (Table 10).

Sensitivity analysis

The results of the sensitivity analysis to assess the impact of the time the questionnaire was answered were similar to those based on primary analysis.

Discussion

In this study, the main finding is that most GPs report compliance with standards for waiting times for in-person office consultations and remote contacts, but they do so at the expense of work overload.

GPs reported working on average 49 h a week in Family Practices of the Portuguese NHS, excluding paid overtime. Many GPs reported regularly working 60 or more hours per week. This is substantially more than the findings of previous research [31, 32] and exceeds the maximum of 40 regular weekly hours mandated by Portuguese law. Weekly hours reported by GPs across European countries has ranged from 33 to 51 h [32]. Lately, both increasing and decreasing trends were found in GP working hours in Europe [33, 34]. Excessive working hours may be related to extra tasks assigned to GPs during the pandemic, with no change in traditional tasks. Other explanations may be unrelated to the pandemic. The demand for health care has been growing due to increasing list size, aging of the population, growing medical complexity of patients, and increased work by GPs due to long waiting times for hospital appointments. Also, excessive bureaucracy in Portugal leads to the request of many medical reports and certificates that are not health care driven. Excessive workload should be a concern because it is one of the factors leading to professional burnout [35, 36], and adverse patient outcomes [37]. Work overload is also associated with intention to leave the profession [38]. The shortage of GPs working for the NHS is growing in Portugal, as in other primary care-based systems [39]. Despite having one of the highest ratio of GPs to inhabitants in OECD countries [12], GPs in Portugal are increasingly choosing to leave the public sector, increasing the proportion of the population with no assigned GP, which is currently over 10% [10]. Reduction in list sizes has been a recurring demand from Portuguese GP unions and professional associations [40]. Freeing GPs from excessive bureaucracy-driven work and from low value care may also control workload and improve productivity, and health outcomes [41, 42]. Some degree of task shifting may be necessary, provided it is informed by research, in order to keep the benefits of the discipline [43, 44].

In-person office consultations accounted for the largest share of the GPs workload, followed by remote care and by COVID-19 related work. Previous research in Portugal found that in-person visits occupied a bigger share of the workload, but in less hours per day [31]. Thereafter, the increase in total hours found in our study has come at the expense of both in-person and remote contacts.

Portuguese Family Practices were reported by participants to be well equipped regarding internet access, but not so regarding telephone equipment and even less so for video consultations. The pandemic has strained telephone access to primary care [45] and it was seen as an opportunity for improvement [46]. However, GPs stated they lacked the time for remote contacts and would not be willing to increase telephone contacts, even if systems improved or it was valued in appraisal. Furthermore, varying informatic literacy among different population groups may modulate these findings.

Waiting times for in-person office consultations and for most remote contacts were most often reported to comply with maximum waiting times (MWT) or 3 working days (if MWT were not defined). This findings need confirmation given that non-compliance has been reported [9, 13]. However, most GPs consider they do not have enough time for non-urgent consultations or for remote contacts, even though they find the latter to be helpful. The mean consultation length in Portuguese Family Practices has been estimated as 16 min [31], one of the longest in the world [47]. However, the trade-off between consultation length and the number of consultations available may be hard to manage. Lack of time for tasks considered to be important exacerbates overload. Home visits were the only contact most often reported to have waiting times longer than the MWT of 24 h. Given that most GPs considered they had enough time for home visits, this MWT may need review. Access for the discussion of questions from patients, both by the practice phone line and by e-mail access, was also reported by most GPs. However, most GPs stated they would do fewer remote contacts if they had enough time for in-person consultations. GPs may be using remote contacts to help them cope with increasing demand. Remote care is better accepted by GPs and their patients when there is an established doctor-patient relationship [48]. This ongoing relationship requires nurturing. Research has highlighted accessibility to GPs as inextricable from continuity [49]. Moreover, to prevent widening the digital divide, remote access must be kept as an add-on and traditional channels must be preserved [50, 51]. Remote care cannot limitlessly replace in-person care, solely in the interest of coping with demand [52].

Young GPs were more likely to report non-compliance with MWT. Non-compliance was not associated with list size, Family Practice organizational model, or total working hours. Younger age was also associated with provision of more restricted access to telephone and e-mail contacts. Early in their careers, GPs are more exposed to time stress [53]. This may be related to being less experienced in managing workload or because it takes time to get to know patients and establish therapeutic relationships. Moreover, shorter duration of relationships between young GPs and their patients may lead to less acceptance of remote care [48]. When remote access is restricted, it may be more difficult to manage demand. It is unlikely that the composition of the lists of younger doctors can explain longer waiting times. Younger doctors do not select lists of younger patients but most often inherit the list of an older doctor who retires or of a colleague who leaves the practice. Practice lists tend to be similar within a given Family Practice in terms of age, gender, and health problems presented. Beyond the activities mandated by quality indicators in pay-for-performance schemes, additional procedures such as minor surgery or home visits may characterize individual practices. A future study of the task profile of GPs in Portugal by age would be helpful in clarifying this.

Other GP factors were associated with waiting times and with the provision of remote access but in a less consistent pattern. GPs working in the North region most often reported non-compliance with MWT for non-urgent consultations. Consumer surveys and monitoring of MWT in Portuguese Family Practices confirms higher rates of non-compliance with waiting times for non-urgent consultations in the North region [9, 13]. These findings warrant reflexion, as the North region is where the shortage of GPs is less of a problem. GPs from the Centre region most often reported requiring more than 3 working days to return a phone call or reply to an e-mail, or to provide a remote medical report, and more often reported provision of restricted access to telephone contacts. This may be explained by a local organizational culture trading off in-person consultations against remote care.

GPs working in Model B Family Practices, followed by those working in Model A, less often reported waiting times over MWT for non-urgent consultations, and less restrictions on e-mail access. This may be because waiting times are part of the quality framework in place in pay-for-performance schemes of Model B Family Practices. On the other hand, GPs in ‘UCSP’ clinics have the additional task of caring for patients with no assigned GP, rendering them less available to their own patients.

GPs reporting waiting times up to 3 working days to respond to remote requests for medical reports and to review test results had larger list sizes than those who reported requiring more than 3 working days. GPs providing broad access through work mobile telephones and e-mail, had average larger list sizes. This may mean that, to cope with demand, GPs with larger lists are more prone to provide faster and broader remote access.

Questions about video consultations and access to patient information on the NHS patient portal (launched in 2013) got the highest proportion of ‘never used’ and neutral views, suggesting slow adoption by GPs. In the case of video consultations, this may be due to the lack of perceived benefit [54] or to the restricted availability of video equipment. Limited use of the patients’ NHS internet portal by GPs may be related to lack of perceived benefit, work overload, or online fatigue [55].

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study in Portugal exploring GPs’ resources, experiences, and views on accessibility to their care, considering both in-person and remote contacts. The pandemic made it even more relevant to address accessibility, due to the restrictions to in-person access and to the expansion of remote access. A patient survey was conducted simultaneously to achieve a comprehensive perspective.

The study has some limitations. First, the questionnaire used has not been validated. However, it was based on validated, published questionnaires assessing accessibility. It has been subjected to face and content validation and a pilot study informed its final version.

Second, the response rate was low, limiting generalizability of results. GPs were recruited as a census but less than 10% of recipients of the invitation to participate clicked on the link to the questionnaire. However, 60% of those who opened the questionnaire answered it and there were participants from every Health Centres Group in continental Portugal. To maximize the response rate, an e-mail reminder was sent, appeals for participation were made on social media, and the study period was expanded. Participants were younger than the population of GPs working in Portugal, and GPs working in the Centre region and Model B Family Practices were over-represented. Younger GPs, lacking the experience of their older colleagues, may require more time for consultations and hence generate longer waiting times for appointments. In model B clinics, the pay-for-performance scheme rewards compliance with maximum waiting times, but the demands of keeping up with all the standards of quality indicators may also result in longer waiting times for patients. GPs training Family Medicine residents were also over-represented in this study as around 20% of GPs are estimated to be trainers. Training may affect waiting times in opposite ways: the time demands of training may increase waits, but the extra work force of residents may decrease them. The low response rate may be partly explained by the increase in workload GPs are experiencing, and by online fatigue [55].

Third, survey studies are prone to information biases. Asking questions to the past 4 weeks of practice sought to minimize recall bias when answering about usual practices. Self-report of working hours and compliance with standards for waiting times may be over-estimated, but the possibility of under-estimation cannot be ruled out either [56]. The limit of 60 to the maximum weekly hours that could be reported may have decreased the median weekly working hours as it was criticised by several participants who reported to work over 60 h a week. Under-reporting bias may arise in questions addressing practices (like waiting times) that, even with anonymity, may produce an undesirable collective picture. GPs struggling to comply with MWT may find it harder to participate in research [57]. The results of the patient survey on accessibility to GPs that was launched simultaneously will shed light on these findings.

Conclusions

A persistent excess of regular and unpaid working hours by GPs needs confirmation and monitoring. If unpaid overtime is persistently necessary to meet the regular demands of work, then workload in general and specific allocated tasks warrant review. Reduction in list sizes and freeing GPs from excessive bureaucracy-driven work and from low value care need to be considered. GPs’ preferences for more in-person care than was feasible during the pandemic must be considered when planning for the post pandemic reconfiguration of service delivery. Future research should focus on younger GPs, as they seem especially vulnerable to restricted accessibility. Clarifying if the age differences found are generational (possibly related to a stronger drive to secure work-life balance), or an attribute of early career GPs (lacking clinical experience, in the process of building relationships with their patients, or experiencing childcare challenges), could allow for targeted interventions.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Change history

01 December 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-023-02220-4

Abbreviations

- GP:

-

General Practitioners

- MWT:

-

Maximum waiting times

- NHS:

-

National Health Service

References

Lemire F. First contact: what does it mean for family practice in 2017? Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:256.

Gulliford MC. Availability of primary care doctors and population health in England: Is there an association? J Public Health Med. 2002;24(4):252–4.

Starfield B. Accessibility and First Contact: The Gate. In: Primary Care - Balancing Health Needs, Services, and Technology. New York: Oxford Uni; 1998. p. 119–41.

Royal College of General Practitioners. General practice in the post Covid world. 2020. Available from: https://www.rcgp.org.uk/getmedia/4a241eec-500b-44f7-96fe-0e63208f619b/general-practice-post-covid-rcgp.pdf

Rawaf S, Allen LN, Stigler FL, Kringos D, Quezada Yamamoto H, van Weel C. Lessons on the COVID-19 pandemic, for and by primary care professionals worldwide. Eur J Gen Pract. 2020;26(1):129–33.

Albert SL, Paul MM, Nguyen AM, Shelley DR, Berry CA. A qualitative study of high-performing primary care practices during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Fam Pract. 2021;22(1):1–7. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-021-01589-4. cited 2021 Nov 29.

Simões J de A, Augusto GF, Fronteira I, Hernández-Quevedo C. Portugal Health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2017;19(2):1–184. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/337471/HiT-Portugal.pdf.

Ministério da Saúde [Ministry of Health]. Portaria n.o 153/2017 de 4 de maio [Ordinance nr. 153/2017. May the 4th]. Diário da República 2017 p. 2204–9. Available from: https://dre.pt/home/-/dre/106970981/details/maximized.

Entidade Reguladora da Saúde [Regulatory Authority of Health]. Informação de Monitorização sobre Tempos de Espera no SNS - 1.o e 2.o Semestres de 2019 [Information on the Monitoring of NHS Waiting Times - 1st and 2nd Semesters 2019]. 2020. Available from: https://www.ers.pt/pt/regula cited 2022 Feb 20

Ministério da Saúde [Ministry of Health]. Acesso a cuidados de saúde nos estabelecimentos do SNS e entidades convencionadas - Relatório Anual 2021 [Access to health care in NHS institutes and allied partners - 2021 annual report]. 2022.

Ponte C, Lima G, Granja M. Use and attitudes towards telephone and e-mail communication between doctors and patients: a survey of general practitioners working in Matosinhos Local Health Unit. Rev Port Med Geral Fam. 2022;38:258–68.

OECD. Health at a Glance 2021 - OECD Indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2021. Available from: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/ae3016b9-en/index.html?itemId=/content/publication/ae3016b9-en.

Carvalho B. Centros de saúde: um mês à espera da consulta [Family Practices: one month wait for a consultation]. Deco Proteste. 2019. Available from: https://www.deco.proteste.pt/saude/hospitais-servicos/noticias/centros-de-saude-um-mes-a-espera-da-consulta cited 2022 Feb 21

Ferreira PL, Raposo V. Monitorização da satisfação dos utilizadores das USF e de uma amostra de UCSP [Monitoring patient satisfaction in Family Health Units and in a sample of UCSP units]. 2015. Available from: http://www2.acss.minsaude.pt/Portals/0/2015.08.24-Relatório_Final-VF.pdf.

Direção-Geral da Saúde [Directorate-General for Health]. Covid-19: primeira fase de mitigação - Medidas transversais de preparação [COVID-19: first mitigation phase - general preparedness measures]. 2020. Available from: https://covid19.min-saude.pt/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/i026005.pdf

G20 Digital Health Taskforce. Digital Health Implementation approach to Pandemic Management. 2020. Available from: https://digitalhealthtaskforce.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/G20-2020-Digital-Health-Implementation-approach-to-Pandemic-Management.pdf cited 2021 Jan 23

Direção-Geral da Saúde [Directorate-General for Health]. Norma 004/2020 COVID-19: Fase de mitigação [Guideline 004/2020 COVID-19: Mitigation phase][Internet]. 2020. Available from https://www.omd.pt/content/uploads/2020/03/20200323-covid19-dgs-norma-0042020-mitigacao.pdf.

Ministério da Saúde [Ministry of Health]. Matriz de Indicadores dos Cuidados de Saúde Primários - Sistema de Informação e Monitorização do Serviço Nacional de Saúde [Matrix of Primary Health Care Indicators - Information and Monitoring System of the National Health Service]. Microsoft Power BI. 2021. Available from: https://bicsp.min-saude.pt/pt/investigacao/Paginas/Matrizindicadorescsp_publico.aspx?isdlg=1 cited 2022 Feb 11

Campbell J, Smith P, Nissen S, Bower P, Elliott M, Roland M. The GP Patient Survey for use in primary care in the National Health Service in the UK-development and psychometric characteristics. BMC Fam Pract. 2009;10:57. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2296/10/57. cited 2018 Jul 22.

McInnes DK, Brown JA, Hays RD, Gallagher P, Ralston JD, Hugh M, et al. CAHPS® Health Information Technology (HIT) Field Test Items and Response Scales. 2012. p. 47–8.

Mead N, Bower P, Roland M. The General Practice Assessment Questionnaire (GPAQ)-Development and psychometric characteristics. BMC Fam Pract. 2008;9:13. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2296/9/13. cited 2018 Jul 29.

Shi L, Starfield B, Xu J. Validating the Adult Primary Care Assessment Tool. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(2):161–75.

Howard M, Agarwal G, Hilts L. Patient satisfaction with access in two interprofessional academic family medicine clinics. Fam Pract. 2009;26(5):407–12.

Schäfer WLA, Boerma WGW, Kringos DS, De Ryck E, Greß S, Heinemann S, et al. Measures of quality, costs and equity in primary health care instruments developed to analyse and compare primary care in 35 countries. Qual Prim Care. 2013;21(2):67–79.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Topics: Access to Health Care. Available from: https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_stats/MEPS_topics.jsp?topicid=1Z-1 cited 2018 Aug 17

Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec. Measuring Organizational Attributes of Primary Healthcare: A Scanning Study of Measurement Items Used in International Questionnaires [Internet]. 2014. Available from https://www.inspq.qc.ca/pdf/publications/1857_Measuring_Organizational_Primary_HealthCare.pdf.

Canadian Medical Association. CMA Workforce Survey. 2017. Available from: https://www.cma.ca/Assets/assets-library/document/en/advocacy/policy-research/cma_survey_workforce2017_questionnaire-e.pdf cited 2018 Jul 15

Kringos DS, Boerma WG, Bourgueil Y, Cartier T, Hasvold T, Hutchinson A, et al. The european primary care monitor: structure, process and outcome indicators. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11:81.

Ministério da Saúde [Ministry of Health]. Relatório Social do Ministério da Saúde e do Serviço Nacional de Saúde [Social Report of the Ministry of Health and of the National Health Service]. 2018;240. Available from: https://www.sns.gov.pt/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Relatório-Social-MS_SNS-2018-002.pdf

Ordem dos Médicos [Portuguese Medical Board]. Estatísticas 2021 - Estatísticas por especialidade [2021 Statistics - statistics by medical specialty]. Vol. 15. 2016. p. 1–23. Available from: https://ordemdosmedicos.pt/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/ESTATISTICAS_ESPECIALIDADES_2021.pdf

Granja M, Ponte C, Cavadas LF. What keeps family physicians busy in Portugal? A multicentre observational study of work other than direct patient contacts. BMJ Open. 2014;4(6):e005026. Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/4/6/e005026#.

Schäfer WLA, Van Den Berg MJ, Groenewegen PP. The association between the workload of general practitioners and patient experiences with care: results of a cross-sectional study in 33 countries. Hum Resour Health. 2020;18:76. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-020-00520-9. cited 2021 Oct 26.

Crosbie B, O’Callaghan ME, O’Flanagan S, Brennan D, Keane G, Behan W. A real-time measurement of general practice workload in the Republic of Ireland: a prospective study. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(696):e489. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7274543/.

Odebiyi B, Walker B, Gibson J, Sutton M, Spooner S, Checkland K. Eleventh National GP Worklife Survey 2021. 2021. Available from: https://prucomm.ac.uk/assets/uploads/Eleventh_GPWLS 2021.pdf cited 2022 Sep 4

Tetzlaff ED, Hylton HM, Ruth KJ, Hasse Z, Hall MJ. Association of Organizational Context, Collaborative Practice Models, and Burnout Among Physician Assistants in Oncology. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022;OP2100627. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35061507 cited 2022 Feb 23

Meredith LS, Bouskill K, Chang J, Larkin J, Motala A, Hempel S. Predictors of burnout among US healthcare providers: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e054243. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-054243. cited 2022 Aug 31.

Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S, Trojanowski L. The relationship between physician burnout and quality of healthcare in terms of safety and acceptability: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(6). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28637730/ cited 2022 Feb 23

Owen K, Hopkins T, Shortland T, Dale J. GP retention in the UK: a worsening crisis. Findings from a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2019;9(2). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30814114/ cited 2022 Feb 23

Ikpoh M, Marshall M. The workforce crisis in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2022;72(718):204–5. Available from: https://bjgp.org/content/72/718/204. cited 2022 Aug 7.

Associação Portuguesa de Medicina Geral e Familiar [Portuguese Association of Family Medicine/General Practice]. Fórum Médico reuniu parceiros do setor para debater dimensão das listas dos MF [Medical Forum gathered partners to debate the dimension of patients’ lists]. 2018. Available from: https://apmgf.pt/2018/03/07/forum-medico-reuniu-parceiros-do-setor-para-debater-dimensao-das-listas-dos-mf/ cited 2022 Feb 23

Jones R. General practice in the years ahead: relationships will matter more than ever. Br J Gen Pract. 2021;71(702):4–5. Available from: https://bjgp.org/content/71/702/4. cited 2021 Oct 26.

McCartney M. Medicine: before COVID-19, and after. Lancet. 2020;395(10232):1248–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30756-X.

Gibson J, Francetic I, Spooner S, Checkland K, Sutton M. Primary care workforce composition and population, professional, and system outcomes: a retrospective cross-sectional analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2022;72(718):e307-15. Available from: https://bjgp.org/content/72/718/e307 cited 2022 Aug 7.

Jones R. Deconstructing the doctor. Br J Gen Pr. 2017;67:387. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp17X692177. cited 2021 Oct 26.

Campos A. Centros de saúde não conseguem atender telefones. Quebra nas consultas presenciais é de três milhões [Family Practices can’t manage to answer the telephone. Three million drop in consultations]. Público. 2020; Available from: https://www.publico.pt/2020/07/31/sociedade/noticia/centros-saude-nao-conseguem-atender-telefones-quebra-consultas-presenciais-tres-milhoes-1926354 cited 2020 Jul 31

Marshall M, Howe A, Howsam G, Mulholland M, Leach J. COVID-19: a danger and an opportunity for the future of general practice. Vol. 70, The British journal of general practice : the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners. NLM (Medline); 2020. p. 270–1. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp20X709937 cited 2020 Aug 2

Irving G, Neves AL, Dambha-Miller H, Oishi A, Tagashira H, Verho A, et al. International variations in primary care physician consultation time: a systematic review of 67 countries. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e017902.

Mozes I, Mossinson D, Schilder H, Dvir D, Baron-Epel O, Heymann A. Patients’ preferences for telemedicine versus in-clinic consultation in primary care during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Prim Care. 2022;23:33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-022-01640-y. cited 2022 Feb 28.

Voorhees J, Bailey S, Waterman H, Checkland K. Accessing primary care and the importance of ‘human fit’:a qualitative participatory case study. Br J Gen Pract. 2022;72(718):e342–50 (BJGP.2021.0375).

Castle-Clarke S, Imison C. The digital patient: transforming primary care? 2016. Available from: https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/files/2017-06/1497259872_nt-the-digital-patient-web-corrected-p46-.pdf cited 2018 Apr 1

Eberly LA, Kallan MJ, Julien HM, Haynes N, Khatana SAM, Nathan AS, et al. Patient Characteristics Associated With Telemedicine Access for Primary and Specialty Ambulatory Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2031640. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2774488. cited 2021 Jan 2.

Dawnay G. Is this really doctoring? Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(698):455–455. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp20X712445. cited 2020 Aug 28.

Von Dem Knesebeck O, Koens S, Marx G, Scherer M. Perceptions of time constraints among primary care physicians in Germany. BMC FamPract. 2019;20:142. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-019-1033-5. cited 2019 Nov 17.

Greenhalgh T, Ladds E, Hughes G, Moore L, Wherton J, Shaw SE, et al. Why do GPs rarely do video consultations? qualitative study in UK general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3399/BJGP.2021.0658.

Bonanomi A, Facchin F, Barello S, Villani D. Prevalence and health correlates of Online Fatigue: A cross-sectional study on the Italian academic community during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One. 2021;16(10):e0255181. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34648507/.

Chang C hsu J, Menéndez CC, Robertson MM, Amick BC, Johnson PW, Del Pino RJ, et al. Daily self-reports resulted in information bias when assessing exposure duration to computer use. Am J Ind Med. 2010;53(11):1142–9.

Dahrouge S, Armstrong CD, Hogg W, Singh J, Liddy C. High-performing physicians are more likely to participate in a research study: findings from a quality improvement study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19(1):171. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0809-6. cited 2020 May 16.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank: the Portuguese Medical Board for the cooperation in the recruitment of General Practitioners; the residents who participated in the pilot study; the General Practitioners who participated in the face and content validation of the questionnaire and all who answered the questionnaire; John Yaphe for the critical review of the revised version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study has not received any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MG Conceived and designed the study protocol, including objectives, building of the questionnaire, recruitment strategy, and analysis, collected the data, performed the analysis, and wrote the paper. SC Conceived and designed the study protocol, including objectives, building of the questionnaire, recruitment strategy, and analysis, and critically reviewed the paper. LA Conceived and designed the study protocol, including objectives, building of the questionnaire, recruitment strategy, and analysis, and critically reviewed the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Matosinhos Local Health Unit on 10/07/2020 (nr. 56/CE/JAS). Information about the study scope and aims and about its voluntary nature was summarized in the main header of the questionnaire (Supplementary File 1). A link in the main header directed General Practitioners to more detailed information, such as the study aims, institutional affiliations of the researchers, the anticipated benefits and the discomfort it may entail, the right to refuse to participate, and the contacts of the researchers. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable, the questionnaire was to be answered online and submitted anonymously.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: The author reported that author names for reference 32 is incorrect. It should be corrected to “Schäfer WLA, Van Den Berg MJ, Groenewegen PP”.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Granja, M., Correia, S. & Alves, L. Access to General Practitioners during the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic in Portugal: a nationwide survey of doctors. BMC Prim. Care 24, 46 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-023-01994-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-023-01994-x