Abstract

Background

To understand how best to approach dementia care within primary care and its challenges, we examined the evidence related to diagnosing and managing dementia within primary care.

Methods

Databases searched include: MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO and The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews from inception to 11 May 2020. English-language systematic reviews, either quantitative or qualitative, were included if they described interventions involving the diagnosis, treatment and/or management of dementia within primary care/family medicine and outcome data was available. The risk of bias was assessed using AMSTAR 2. The review followed PRISMA guidelines and is registered with Open Science Framework.

Results

Twenty-one articles are included. The Mini-Cog and the MMSE were the most widely studied cognitive screening tools. The Abbreviated Mental Test Score (AMTS) achieved high sensitivity (100 %, 95 % CI: 70-100 %) and specificity (82 %, 95 % CI: 72-90 %) within the shortest amount of time (3.16 to 5 min) within primary care. Five of six studies found that family physicians had an increased likelihood of suspecting dementia after attending an educational seminar. Case management improved behavioural symptoms, while decreasing hospitalization and emergency visits. The primary care educational intervention, Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (Department of Veterans Affairs), was successful at increasing carer ability to manage problem behaviours and improving outcomes for caregivers.

Conclusions

There are clear tools to help identify cognitive impairment in primary care, but strategies for management require further research. The findings from this systematic review will inform family physicians on how to improve dementia diagnosis and management within their primary care practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

At any given time, 5–8 % of the general population aged 60 and over are living with dementia, and it is expected that 152 million people in the world will have dementia by 2050 [1]. The impact of dementia is far reaching, as it affects not only the person with dementia, but also their family carers, the healthcare system and society as a whole [1]. Dementia is often unrecognized, and there is an underuse of diagnostic assessment tools and a lack of attention to the issues faced by family caregivers [2]. Approximately 65 % of dementia cases are undiagnosed in primary care, which negatively impacts these patients by not implementing advanced care planning and management strategies before the dementia progresses [3]. The U.S Preventative Services Task Force recommends that clinicians assess cognitive functioning when a patient is suspected of cognitive impairment based on the physician’s observation or caregiver concerns [3]. Canadian consensus guidelines similarly do not recommend asymptomatic screening, but instead suggest use of validated screening tools if there is clinical concern for a cognitive disorder [4]. Common neuropsychological screening tools administered by family physicians (FPs) include the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and Clock Drawing Test (CDT) [3]. However, it is not clear that these are the best screening tools for use in primary care.

Time constraints are often an issue for family doctors as it relates to diagnosing and managing dementia. The time allocated for a typical office visit makes it challenging to perform a cognitive assessment [5]. FPs often feel uncertainty regarding the management of dementia after a diagnosis has been made [5]. This highlights the current need to better optimize dementia care within primary care. The objective of this systematic review of systematic reviews was to determine the most effective evidence-based strategies to diagnose and manage dementia within primary care. Specifically, we seek to understand what practices FPs can undertake to ensure accurate and timely testing and management.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance to PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses) guidelines [6], and the protocol is registered in Open Science Framework [DOI https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/E4AW5]. All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article in Additional file 1: Appendixes 1 and 2. A systematic review of systematic reviews was determined to be the past method to further summarize and tailor the current body of literature on this topic into a format that would address the existing evidence to practice gap.

Data Sources

The systematic literature search was developed in consultation with a health sciences librarian, with the final search being completed 11 May 2020. The following databases using the Ovid platform were searched without a restriction to publication date: MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO and The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. We searched the following clusters of search terms: Family Practice and Dementia. In each category, we used controlled vocabulary such as Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) as well as keywords. Within each cluster, terms were combined with OR, and between the clusters with AND. We then used CADTH search terms for the systematic review study designs [7] (Additional file 1: Appendix 1). The reference list of a previous relevant systematic review of systematic reviews published in 2014 was also searched [8].

Study Selection

Systematic reviews were considered if they met the following inclusion criteria.

-

Population: Primary care or family practice settings seeing persons with dementia.

-

Intervention: The detection, diagnosis, treatment and/or management of dementia including models of care, pathways and/or protocols.

-

Comparators: Usual care, wait-list control or other interventions within the scope of the review.

-

Outcomes: The description of the detection, diagnosis, treatment or management strategies, along with measures of their acceptability, efficacy or effectiveness in the provision of care.

-

Study design: Systematic review, either quantitative or qualitative.

Articles were also selected for inclusion if they were English-language articles, included relevant descriptions of the interventions used, and outcome data was available.

Two reviewers (B.F and J.H.-L.) independently screened the titles and abstracts for possible inclusion. If either reviewer thought the citation was relevant or potentially relevant, the full-text article was then retrieved for further evaluation. All full-text articles were assessed independently for inclusion by B.F and J.H.-L. Any conflicts were resolved through discussion. One reviewer (B.F.) independently extracted the following information from the included full-text studies using a standardized data extraction form: authors, year of publication, country where the review was conducted, number of studies included, study designs included, databases searched, time frame of article search, inclusion and exclusion criteria, population (mean age, SD and dementia diagnosis), intervention, comparator, sample size, setting (if the intervention was cognitive screening, the method of administration), time of administration (if intervention was cognitive screening), cognitive outcome(s) measured, results (meta-analysis, Sn, Sp, accuracy), and other (Additional file 1: Appendix 2). One reviewer (B.F) categorized each study based on the primary category of intervention, which was verified by another reviewer (J.H-L).

Quality Assessment and Analysis

Two reviewers (B.F and J.H.-L.) independently assessed the quality of the included studies using the AMSTAR 2 Systematic Review Quality Appraisal Checklist 2020. Systematic reviews without a clear PICO were excluded. Best practices for quality assessment using AMSTAR 2 are to consider the impact of inadequate ratings for each category rather than generate an overall score. The AMSTAR 2 quality appraisal results for each of the included studies is available in Additional file 1: Appendix 3 [9]. A qualitative descriptive summary of the literature is presented.

Results

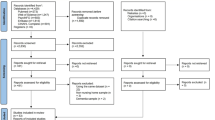

The initial search identified 417 unique citations for possible inclusion after duplicates were removed. After searching the reference list of a relevant previous systematic review of systematic reviews [8], three additional citations were collected and screened for eligibility. After screening the 420 citations, 369 were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. From the 51 full-text articles screened, 30 articles were excluded. Reasons for exclusion include not being a systematic review (n = 20), describing a setting other than primary care (n = 1), failing to describe the intervention (n = 3), or a poor AMSTAR 2 rating (n = 6). This resulted in the inclusion of 21 articles (Fig. 1). The included studies were published between June 2003 and July 2019.

Screening tools

Nine [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18] out of the 21 included systematic reviews describe screening tools for use in primary care (Table 1). Various screening tools, assessing cognitive impairment or dementia, were compared in terms of cognitive outcomes assessed, time to administer, and sensitivity and specificity. The MMSE was used as a reference standard in the majority of the included studies. The Mini-Cog (n = 5) and the MMSE (n = 7) were the most widely studied tools among the included reviews. The Mini-Cog takes approximately 3 min to administer, and sensitivity ranges from 76 to 100 % and specificity from 27 to 93 % [10, 12, 14, 17] depending upon the cut-off value used.

Five systematic reviews examining the MMSE found that it took between 4 and 15 min to administer depending upon the severity of dementia [12,13,14,15,16]. One study found a cut point of 17 had a higher specificity (93 %, 95 % CI: 89-96 %) than a cut point of 24 (46 %, 95 % CI: 40-52 %), while the sensitivity fell from 100 % (95 % CI: 95-100 %) to 70 % (95 % CI: 59-80 %) respectively [16].

The Abbreviated Mental Test Score (AMTS) achieved high sensitivity (100 %, 95 % CI: 70-100 %) and specificity (82 %, 95 % CI: 72-90 %) [12] compared to a clinical reference standard, and took the shortest amount of time (3.16 to 5 min) [12, 14] within primary care. The AMTS was validated for use in general practice [12].

Diagnostic accuracy and physician education

The diagnosis of dementia by FPs varies but is generally low, as reported in 3 different systematic reviews [11, 16, 19]. In an (urban/rural) study, when following usual practice, only half of cases of mild dementia were diagnosed by the FP [19]. In a separate review, un-diagnosed dementia accounted for 50 − 66 % of all cases of dementia in three primary care samples studied [11, 20,21,−22]. Another review reported that the recognition of cognitive impairment in usual practice achieved a detection sensitivity of 62.8 % (95 % CI: 38.0-84.4 %) and specificity of 87.3 % (n = 3; 95 % CI: 84.9-89.4 %) [16]. However, medical record notations mentioning dementia were present in only 37.9 % (95 % CI: 26.8-49.6 %) and FPs recorded a definitive dementia diagnosis in the medical record in only 10.9 % (95 % CI: 6.8-15.7 %) of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) cases [16].

Five of six studies found that FPs had an increased likelihood of suspecting dementia after attending an educational seminar [23, 24]. One study found that the length of the educational seminar impacted the degree of knowledge about dementia management [24].

Management of dementia

Decision aids, advanced care planning (ACP), collaboration with a case manager (CM) and practice guidelines are all interventions with variable impact on helping facilitate the management of dementia in primary care [23, 25,26,27,28,−29] (Table 2). A CM in particular, such as a nurse specialized in care of older adults, can be an asset to a primary care team with the collective goal of collaborating towards meeting the needs of the patient-caregiver dyad [30]. In the case management intervention group of a randomized controlled trial, neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia decreased (Mean Effect Size (MES) = 0.88), as well as the numbers of hospital (MES = 0.66) and emergency department admissions (MES = 0.17) [26]. However, it was found that there was a lack of successful implementation of a CM into care teams within primary care because of the absence of CMs within the primary care setting, and 52 % of CMs reported ineffective communication between the CM and FPs [26].

Only one systematic review looked at pharmacological treatments in the context of primary care [11]. There was no clinically important difference observed on neuropsychiatric symptoms between patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease taking cholinesterase inhibitors versus placebo [11].

Supporting caregivers of people with dementia

FPs reported feeling highly involved in dementia care [31]. However, family caregivers reported that communication with the FPs was unsatisfactory, specifically around awareness of daily care problems (e.g. neuropsychiatric symptoms) [31]. The primary care educational intervention, Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (Department of Veterans Affairs) (REACH VA), involves a trained coach who provides sessions to the caregiver on topics relating to self-care, problem solving, mood management and stress management [32]. REACH VA was successful at increasing carer ability to manage problem behaviours and improved outcomes for caregivers, such as decreased burden, depression and caregiving frustrations [30, 31]. A meta-analysis showed that 58 % (95 % CI: 43-72 %) of family caregivers were in favor of early dementia diagnosis, 50 % (95 % CI: 35-65 %) needed education on dementia, and 23 % (95 % CI: 17-31 %) needed in-home support [33].

Discussion

This systematic review of systematic reviews identified evidence to inform processes for diagnosis and management of dementia within primary care. While the diagnostic accuracy of a tool may be high, the time taken to administer the tool and copyright limitation for tool use are also important to consider in the context of a busy primary care office. The MMSE, which is copyrighted, may not be the best test for use in general practice. Instead, the AMTS appears to be the most suitable tool for use in a busy primary care office, as it has good diagnostic accuracy, does not appear to be copyright protected and takes less time to administer than the MMSE [12, 14, 15]. The Mini-Cog is also quick to administer, and a Cochrane systematic review evaluating the Mini-Cog across care settings recommended that the Mini-Cog be used initially as a case finding test to identify patients who would benefit from additional cognitive evaluations for dementia [34]. However, the sensitivity of the Mini-Cog may not be high enough to be considered useful in primary care [17], as too many cases would be missed.

The current literature suggests that the implementation of case management directly into the primary care setting can be of great benefit to the patient-caregiver dyad, as well as to the health care system. The CM can help facilitate the advanced care planning process [29], as well as decrease the frequency of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia, symptoms of depression, hospital admissions and length of stay in hospital; caregivers can also benefit by experiencing decreased burden and depression [26]. A Cochrane review evaluating the effectiveness of case management in community settings lends support to dementia case management, finding that carer burden decreased and fewer patients where institutionalized after 6 months [35]. Further, there was a reduction in residential home and hospital use after 6 months of case management implementation [35]. There is however a lack of evidence related to cost effectiveness of case management. Facilitating successful case management and advanced care planning includes early implementation while cognitive decline is mild, involving all stakeholders (caregiver, patient, family and FP), and fostering a good relationship between the FP and patient-caregiver dyad [29]. The CM should be physically present in the primary care setting, clearly explain their role to all stakeholders, implement high-intensity case management, and communicate frequently to all stakeholders in order to ensure positive outcomes for the patient-caregiver dyad [26, 27].

Combining educational seminars for FPs with dementia case management may be the best management strategy [23, 24]. Educational interventions focused on dementia diagnosis and management in the context of primary care increased the likelihood of FPs suspecting dementia, while also improving the experience of the family caregiver and the patient [23, 24].

There was limited evidence concerning the use of pharmacological interventions for the treatment of dementia within the primary care setting. Unfortunately, many pharmacologic studies do not focus on primary care or FPs, making it difficult to draw conclusions about the approach to take regarding the use of medications in this context. One systematic review found no clinically important differences between groups receiving cholinesterase inhibitors and those receiving a placebo in the development of behavioral and neuropsychiatric symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease [11]. Similarly, cholinesterase inhibitor use was found to have uncertain clinical benefit in a recent systematic review that explored the benefits and harms of prescription drugs for the treatment of Alzheimer disease, regardless of care setting [36]. This recent review also found limited benefit for memantine.

Conclusions

The AMTS is suitable for detecting dementia within primary care given its high sensitivity and short administration time. To improve dementia identification, FPs should participate in educational interventions. Incorporation of CMs into the primary care team can help with dementia management and result in improved outcomes. There is limited evidence supporting the benefit for pharmacological treatments in the context of primary care.

Limitations and Future Research

A limitation of this systematic review of systematic reviews includes the exclusion of possibly relevant pharmacological reviews, given the fact that we focused on studies conducted in the primary care setting. Future pharmacological studies conducted in the specific context of primary care are needed. Additionally, the results from our review are limited to literature from countries that clearly distinguish primary care from specialist care, given the focus of the search strategy. Lastly, many of the studies included within the identified systematic reviews inappropriately used the MMSE as a reference tool when determining the sensitivity and specificity of various screening tools. Further studies should compare commonly used screening tools within primary care to a recognized gold standard.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article in Additional file 1: Appendixes 1 and 2.

Abbreviations

- FPs:

-

Family physicians

- PRISMA :

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses

- MMSE:

-

Mini-Mental State Examination

- AMTS:

-

Abbreviated Mental Test Score

- ACP:

-

Advanced Care Planning

- CM:

-

Case Manager

- MES:

-

Mean Effect Size

- REACH VA:

-

Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (Department of Veterans Affairs)

References

World Health Organization. Dementia WHO. World Health Organization Dementia. Published September 19, 2019. Accessed August 14, 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia].

Parmar J, Dobbs B, McKay R, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia in primary care: exploratory study. Can Fam Physician Med Fam Can. 2014;60(5):457–65.

Chopra A, Cavalieri TA, Libon DJ. Dementia Screening Tools for the Primary Care Physician. 2007;15(1):9.

Ismail Z, Black SE, Camicioli R, et al. Recommendations of the 5th Canadian Consensus Conference on the diagnosis and treatment of dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2020;16(8):1182–95. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12105

Pimlott NJG, Persaud M, Drummond N, et al. Family physicians and dementia in Canada: Part 2. Understanding the challenges of dementia care. Can Fam Physician Med Fam Can. 2009;55(5):508–509.e1-7.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Strings attached: CADTH database search filters. Strings attached: CADTH Database Search Filters. Published 2016. Accessed May 11, 2020. https://www.cadth.ca/resources/finding-evidence/strings-attached-cadths-database-search-filters#syst

Yokomizo JE, Simon SS, de Campos Bottino CM. Cognitive screening for dementia in primary care: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26(11):1783–804. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610214001082

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. Published online September 21, 2017:j4008. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4008

Abd Razak MA, Ahmad NA, Chan YY, et al. Validity of screening tools for dementia and mild cognitive impairment among the elderly in primary health care: a systematic review. Public Health. 2019;169:84–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2019.01.001

Boustani M, Peterson B, Hanson L, Harris R, Lohr KN. Screening for Dementia in Primary Care: A Summary of the Evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(11):927. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-138-11-200306030-00015

Brodaty H, Low L-F, Gibson L, Burns K. What is the best dementia screening instrument for general practitioners to use? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(5):391–400. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.JGP.0000216181.20416.b2

Creavin ST, Wisniewski S, Noel-Storr AH, et al. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the detection of dementia in clinically unevaluated people aged 65 and over in community and primary care populations. Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group, ed. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Published online January 13, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011145.pub2

Cullen B, O’Neill B, Evans JJ, Coen RF, Lawlor BA. A review of screening tests for cognitive impairment. J Neurol Neurosurg Amp Psychiatry. 2007;78(8):790–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2006.095414

Lischka AR, Mendelsohn M, Overend T, Forbes D. A Systematic Review of Screening Tools for Predicting the Development of Dementia. Can J Aging Rev Can Vieil. 2012;31(3):295–311. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980812000220

Mitchell AJ, Meader N, Pentzek M. Clinical recognition of dementia and cognitive impairment in primary care: a meta-analysis of physician accuracy: Clinical recognition of dementia and mild cognitive impairment. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;124(3):165–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01730.x

Seitz DP, Chan CC, Newton HT, et al. Mini-Cog for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease dementia and other dementias within a primary care setting. Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group, ed. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Published online February 22, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011415.pub2

Smith T, Cross J, Poland F, et al. Systematic Review Investigating Multi-disciplinary Team Approaches to Screening and Early Diagnosis of Dementia in Primary Care – What are the Positive and Negative Effects and Who Should Deliver It? Curr Alzheimer Res. 2017;15(1). https://doi.org/10.2174/1567205014666170908094931

Dungen P, Marwijk HWM, Horst HE, et al. The accuracy of family physicians’ dementia diagnoses at different stages of dementia: a systematic review: The accuracy of family physicians’ dementia diagnoses. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. Published online May 2011:n/a-n/a. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2726

Eefsting JA, Boersma F, Van den Brink W, Van Tilburg W. Differences in prevalence of dementia based on community survey and general practitioner recognition. Psychol Med. 1996;26(6):1223–30. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291700035947

Olafsdóttir M, Skoog I, Marcusson J. Detection of dementia in primary care: the Linköping study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2000;11(4):223–9. https://doi.org/10.1159/000017241

Valcour VG, Masaki KH, Curb JD, Blanchette PL. The detection of dementia in the primary care setting. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(19):2964–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.160.19.2964

Mukadam N, Cooper C, Kherani N, Livingston G. A systematic review of interventions to detect dementia or cognitive impairment: Systematic review of interventions to detect dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;30(1):32–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4184

Perry M, Drašković I, Lucassen P, Vernooij-Dassen M, van Achterberg T, Rikkert MO. Effects of educational interventions on primary dementia care: A systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2479

Davies N, Schiowitz B, Rait G, Vickerstaff V, Sampson EL. Decision aids to support decision-making in dementia care: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2019;31(10):1403–19. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610219000826

Khanassov V, Vedel I, Pluye P. Barriers to Implementation of Case Management for Patients With Dementia: A Systematic Mixed Studies Review. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(5):456–65. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1677

Khanassov V, Pluye P, Vedel I. Case management for dementia in primary health care: a systematic mixed studies review based on the diffusion of innovation model. Clin Interv Aging. Published online June 2014:915. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S64723

Sivananthan SN, Puyat JH, McGrail KM. Variations in Self-Reported Practice of Physicians Providing Clinical Care to Individuals with Dementia: A Systematic Review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(8):1277–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12368

Tilburgs B, Vernooij-Dassen M, Koopmans R, van Gennip H, Engels Y, Perry M. Barriers and facilitators for GPs in dementia advance care planning: A systematic integrative review. Arendts G, ed. PLOS ONE. 2018;13(6):e0198535. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0198535

Greenwood N, Pelone F, Hassenkamp A-M. General practice based psychosocial interventions for supporting carers of people with dementia or stroke: a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17(1):3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-015-0399-2

Schoenmakers B, Buntinx F, Delepeleire J. What is the role of the general practitioner towards the family caregiver of a community-dwelling demented relative?: A systematic literature review. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2009;27(1):31–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/02813430802588907

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Published 2020. https://www.caregiver.va.gov/REACH_VA_Program.asp

Khanassov V, Vedel I. Family Physician-Case Manager Collaboration and Needs of Patients With Dementia and Their Caregivers: A Systematic Mixed Studies Review. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(2):166–77. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1898

Holsinger T, Plassman BL, Stechuchak KM, Burke JR, Coffman CJ, Williams JW. Screening for Cognitive Impairment: Comparing the Performance of Four Instruments in Primary Care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(6):1027–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03967.x

Reilly S, Miranda-Castillo C, Malouf R, et al. Case management approaches to home support for people with dementia. Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group, ed. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Published online January 5, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008345.pub2

Fink HA, Linskens EJ, MacDonald R, et al. Benefits and Harms of Prescription Drugs and Supplements for Treatment of Clinical Alzheimer-Type Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(10):656–68. https://doi.org/10.7326/M19-3887

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Helen Lee Robertson, MLIS, Health Sciences Library, University of Calgary for assisting in the development of the systematic literature search.

Support

B. Fernandes was funded as an Undergraduate Summer Research Student by the Division of Geriatric Medicine, University of Calgary and a MITACS studentship. J. Holroyd-Leduc is the University of Calgary Brenda Strafford Foundation Chair in Geriatric Medicine.

Prior Presentation

None.

Funding

B. Fernandes was funded as an Undergraduate Summer Research Student by the Division of Geriatric Medicine, University of Calgary and a MITACS studentship. J. Holroyd-Leduc is the University of Calgary Brenda Strafford Foundation Chair in Geriatric Medicine. The funders had no role in the collection, analysis or interpretation of data, or in the preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All 3 authors derived the study. BF and JHL reviewed all retrieved citations and manuscripts. All 3 authors analysed the findings. BF drafted the manuscript; JHL and ZG provided critical edits. All 3 authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate:

Not applicable.

Consent for publication:

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Fernandes, B., Goodarzi, Z. & Holroyd-Leduc, J. Optimizing the diagnosis and management of dementia within primary care: a systematic review of systematic reviews. BMC Fam Pract 22, 166 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-021-01461-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-021-01461-5