Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic has shaken the world in early 2020. In France, General Practitioners (GPs) were not involved in the care organization’s decision-making process before and during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. This omission could have generated stress for GPs. We aimed first to estimate the self-perception of stress as defined by the 10-item Perceived Stress Score (PSS-10), at the beginning of the pandemic in France, among GPs from the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, a french administrative area severely impacted by COVID-19. Second, we aimed to identify factors associated with a self-perceived stress (PSS-10 ≥ 27) among socio-demographic characteristics of GPs, their access to reliable information and to personal protective equipment during the pandemic, and their exposure to well established psychosocial risk at work.

Methods

We conducted an online cross-sectional survey between 8th April and 10th May 2020. The self-perception of stress was evaluated using the PSS-10, so to see the proportion of “not stressed” (≤20), “borderline” (21 ≤ PSS-10 ≤ 26), and “stressed” (≥27) GPs. The agreement to 31 positive assertions related to possible sources of stress identified by the scientific study committee was measured using a 10-point numeric scale. In complete cases, factors associated with stress (PSS-10 ≥ 27) were investigated using logistic regression, adjusted on gender, age and practice location. A supplementary analysis of the verbatims was made.

Results

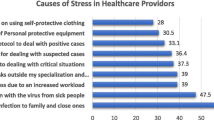

Overall, 898 individual answers were collected, of which 879 were complete. A total of 437 GPs (49%) were stressed (PSS-10 ≥ 27), and 283 GPs (32%) had a very high level of stress (PSS-10 ≥ 30). Self-perceived stress was associated with multiple components, and involved classic psychosocial risk factors such as emotional requirements. However, in this context of health crisis, the primary source of stress was the diversity and quantity of information from diverse sources (614 GPs (69%, OR = 2.21, 95%CI [1.40–3.50], p < 0.001). Analysis of verbatims revealed that GPs felt isolated in a hospital-based model.

Conclusion

The first wave of the pandemic was a source of stress for GPs. The diversity and quantity of information received from the health authorities were among the main sources of stress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In December 2019, the COVID-19 (SARS-COV-2 virus) epidemic started in Wuhan, China [1]. The pandemic state was declared on 11th of March 2020 by the World Health Organization (WHO), and its impact on every part of daily life means the COVID-19 pandemic is one of the most significant events of the twenty-first century.

In France, by August 2020, ~ 100,000 severe cases had been hospitalized and ~ 30,000 deaths had occurred. To tackle the epidemic, the French government applied a strategy which was predefined after the 2009 H1N1 epidemic, and inspired by the Chinese and Italian management of COVID-19 [2]. Several phases were organized, thanks to the Operational Coordination of Epidemic and Biological Risks (COREB), which promoted exchanges between numerous specialists, though excluding General Practitioners (GPs) from the decision process [3].

The first phase aimed to slow down the introduction of the SARS-COV-2 virus on the French territory. The second one consisted of preventing the virus from spreading throughout the country. To do this, it was decided that any patient suspected of COVID-19 would have to be admitted to referral hospitals [4]. On 14th March 2020, 4500 patients had been diagnosed with COVID-19, the critical care units of eastern and northern France, and the Paris area, were being overwhelmed when the French government initiated a national lockdown [5, 6]. In addition to the lockdown, a decision was made to switch the management of mild cases from hospitals to primary care in family practices [7]. During this phase, GPs officially became part of the pandemic response organization and had to adapt their practices and workflow urgently. At the same time, shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE) happened worldwide [8].

The unique and unpredictable nature of this pandemic urged the WHO to warn about the possible occurrence of professional stress and psychological disorders [9].

First, our hypothesis was that due to a lack of initial involvement of GPs in the crisis management and decision-making during the first wave of the pandemic, they might have suffered from professional stress disorders. We also hypothesized that socio-demographic characteristics of GPs, their access to reliable information and to personal protection equipment (PPE) may have mitigated their self-perception of stress.

We first aimed to estimate the self-perception of stress, at the beginning of the pandemic in France, as measured by the 10-item Perceived Stress Score (PSS-10), among GPs from the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, a French administrative area severely impacted by COVID-19, so to see the proportion of “not stressed”, “borderline”, and “stressed” GPs. Then we aimed to identify factors associated with a self-perceived stress (PSS-10 ≥ 27), among socio-demographic characteristics of GPs, their access to reliable information and to PPE during the pandemic, and their exposure to well established psychosocial risk at work.

Methods

Study design and participants

We conducted an online cross-sectional survey of every GP registered in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region, a 7,948,287 inhabitant’s administrative area where the first clusters of cases were reported [10]. The eligibility criteria was to be a GP registered in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes area, agreeing for data collection and analysis. Exclusion criteria was to be a medical student or a GP working exclusively in hospitals. To reach the GPs, we released our survey through the official mailing list of medical professionals’ network for the area (union régionale des professionnels de santé, URPS). This mailing list included 5344 GPs. They were invited to fill an online self-questionnaire, through the software of a private society (GIDE). This cross-sectional survey was conducted from the perspective of a prospective cohort to monitor the self-perceived stress of GPs of the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes area over the first wave of the pandemic. Each GP participating in the survey were asked to be enrolled within the cohort. Herein we are reporting the results of this baseline assessment, composed of answers collected from 8th April to 10th May 2020. Throughout the study period, ~ 10% of French COVID-19 cases and deaths occurred in this area, and the national lockdown was in place.

Measurements

The self-questionnaire was regrouping five main parts: 1) socio-demographic characteristics of GPs, 2) practice and workflow before and during the pandemic, 3) their self-perception of stress according to the PSS-10 validated in French, 4) their agreement with 31 positive assertions to identify potential origin of stress, and 5) an open-ended question (Supplementary Table 1). It was devised by the scientific study committee, involving: 2 residents in family medicine, 2 infectious diseases physicians, 3 specialists in epidemiological studies including prevention of stress at work, and 1 methodologist. It was tested on 12 GPs in a pilot phase to ensure the comprehension and calibration of the questions.

The Perceived Stress Score with 10 items (PSS-10) was used to assess the level of self-perceived stress [11]. It can be self-administered, and is validated for French with a Cronbach’ alpha coefficient above 0.70 [12]. The PSS-10 allocates GPs under three categories: “not stressed” (PSS-10 ≤ 20), “borderline” (21 ≤ PSS-10 ≤ 26), and “stressed” (PSS-10 ≥ 27) [11]. We also identified and analyzed a “very stressed” (PSS-10 ≥ 30) category [11].

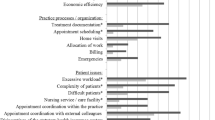

The 31 positive assertions were developed by the scientific study committee to explore the root-causes of stress. They were regrouped under 8 themes: 1) workload (3 assertions); 2) emotional requirements (5 assertions); 3) conflict of values (5 assertions); 4) economic insecurity (2 assertions); 5) working relationships and social reports (4 assertions); 6) personal protection equipment (5 assertions); 7) access to information (4 assertions); and 8) others (3 assertions) [13]. For each affirmation, GPs had to express their agreement using a 10-point numeric scale, ranging from one (“I do not agree at all”) to ten (“I totally agree”). An agreement ≥6/10 was considered as “agree”, while an agreement < 6/10 was considered as “not agree”.

At last, an open-ended question was left to collect any remarks from the GPs. Verbatims of the open-ended question were planned to be analyzed to identify other possible sources of stress.

Data, verbatims and statistical analysis

Data collected were analyzed by the clinical research unit of the Annecy hospital: a statistician for quantitative data and two GPs as independent reviewers for the verbatims analysis. To ensure that the sampling obtained through the mailing was representative of the GP population, we compared the sample’s demographic characteristics to the real demographic characteristics of GPs available at regional level from the URPS in 2020, and at the national level from the French Ministry of Health in 2018. In this cross-sectional study we use Student t-test, Pearson’s correlation test and Chi-squared test for univariate comparison.

In complete cases, we explored factors associated with a self-perceived stress defined as a PSS-10 ≥ 27, using a multivariate logistic regression adjusted for gender, age as continuous value, and practice location. No imputation of missing data was performed. The variable selection was made using a backward elimination based on the Akaike criterion. The associations are represented using odds ratio (OR) with their 95% confidence interval (95CI). The level of significance was set at 5% bilateral. Statistical analysis was performed using the R software version.4.0.2. (the R foundation, Vienna, Austria).

The verbatims of the open-ended question were handled as qualitative data. They were double-read by two independent reviewers. The reviewers extracted and categorized the answers under the 8 themes identified to develop the 31 positive assertions. Whenever the two reviewers could not classify GPs’ answers under existing themes, they confronted their extraction to categorize them under new themes they defined together.

Results

General practitioner population

Over the study period, we collected 1050 GPs’ responses, of whom 5 worked exclusively in the hospital, 6 were not actually in the targeted administrative area, and 141 (13%) have not validated their questionnaire. Therefore, the final set used for analysis was constituted of 898 GPs’ responses (17% of the 5344 emails sent, and 86% of the initial responses), of which 879 were complete.

Table 1 describes GPs’ characteristics. The majority of respondents were women (60.5%) and the average age was 47.7 years. Women were younger than men (44.9 vs. 51.9 years, p < 0.001). The sample was representative of the GP population in the area, with a small gap in gender (61% of women vs. 51 to 54% in the control data from URPS and the French Ministry of Health) and age (47 on average vs. 48 to 52 in control data).

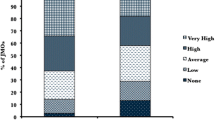

Prevalence of self-perceived stress (PSS-10 score)

Overall, the average PSS-10 score was 26.4 (±6.4): 169 GPs (19%) were “not stressed” (PSS-10 ≤ 20), 292 (33%) “borderline” (21 ≤ PSS-10 ≤ 26), and 437 (49%) “stressed” (PSS-10 ≥ 27). A total of 283 GPs (32%) were “very stressed” (PSS-10 ≥ 30).

Impact of the epidemic on the practice

They were 880 (98%) GPs to adapt their practice and facilities to implement barrier measures. Issues in obtaining protective equipment were reported by 531 (59%) of them. Most of GPs (741, 83%) considered having less work over the study period (Table 2).

Factors associated with stress

Two-third of GPs had someone to talk to (556, 62%), they were mostly supported by their family and friends (617, 69%), and very few had the willingness to withdraw from practice (46, 7%).

Table 3 details the results of the multivariate analysis of complete cases. Over 879 GPs, women were twice as stressed as men (OR = 1.88, 95%CI [1.31–2.72], p < 0.001). In addition to gender, other factors were found being a source of self-perceived stress among the 31 positive assertions: making difficult decisions, being affected by patient anxiety, being overwhelmed by information, having a heavy workload, having the feeling of being alone, and the feeling that work time impacted on personal life. Factors associated with lesser stress were: being in line with the job, having the feeling of being useful, having trust in the future and having the ability to forget work when reaching home.

Analysis of verbatims

We collected 294 answers through the last open-ended question, of which 202 were suitable for verbatims analysis (Supplementary Table 2). A total of 153 verbatims were related to the 8 themes developed for the 31 positive assertions, and 173 verbatims were about 5 new themes. The three main new themes were: 1) The place of GPs in the organization of the response to the health crisis (n = 72); 2) The feeling of GPs during health crisis (n = 67); and 3) New concepts about information and guidelines (n = 36). From these three new themes we could describe three networks for communication around GPs during the health crisis. The first one was between health authorities and GPs. In this first network, the communication was a one-way flow from health authorities to GPs. GPs considered that information they received was too vague, unsuitable to their practice, and sometimes contradictory (n = 58). They described a difficulty to assimilate knowledge as guidelines were frequently modified (n = 29). Few noted that they had the same type and level of information as their patients (n = 8). The second network was a two-way flow between hospitals and GPs, which was sometimes reported as being non-existent (n = 13). This lack of cooperation has led to feelings of frustration and sometimes even guilt (n = 7). The last network was a two-way flow between GPs themselves, and was reported. It has been in many places as being a source of mutual help (n = 29). Finally, GPs had the feeling of being neglected, not taken seriously and not fully considered by health authorities (n = 49), while they were standing alone in the hospital-based response to the pandemic (n = 43).

Discussion

Our survey reveals that the level of stress was very high in GPs during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic within lockdown phase in France, as half of the GPs were stressed (PSS-10 ≥ 27), and a third very stressed (PSS-10 ≥ 30).

A Danish study conducted on 3350 GPs in a non-pandemic period, also using PSS-10, showed that the baseline level of stress can be as high as 21% of GPs, much lower than the 49% observed in our study [14]. Though French and Danish GPs are likely to be not comparable, it is estimated that in Europe, 25% of workers present stress related to work, which is also much lower than the rate we observed [15, 16]. This significantly different rate of stress is likely to be due to the pandemic’s context and the lockdown, though no baseline evaluation of stress in GPs was performed prior to these events. The pandemic was reported as a source of stress in the general population and among hospital medical staff, and there is no reason to consider that GPs were spared [17,18,19].

Besides this stressful context, we identified independent sources of stress. Contrary to popular belief, one of these sources was not the workload, but rather the change in practice. In addition to the reorganization and redesign of facilities, the workload of GPs decreased significantly from 95.1 to 45.2 patients per week. This decrease was confirmed by results from a flash survey conducted by the French government in April 2020 which showed a diminution of consultations for patients with underlying and chronic condition, pediatric and pregnancy follow [20]. On the contrary, an increase in consultations related to psychological distress was observed over the same period [20]. Similar observations were made in England, consultation design was shown to be modified, switching from face-to-face to remote consultations [21]. Those observations corroborated our results about the number of GPs using teleconsultation during the pandemic, from 14% before to 86% during the pandemic. However, neither of these studies, nor ours, analysed a potential link between the change in consultation profile and the subsequent workload, and the occurrence of a self-perceived stress among GPs.

Previous studies showed that GPs aren’t sufficiently trained and prepared for health crises [22, 23]. Although there were predefined plans to respond to a pandemic, we believe it is important to highlight that there was a lack of collaboration between GPs and the health care authorities [24]. It was not limited to the French context, and it appears to be a root-cause of professional stress [24]. In addition, in a context of shortage of protective equipment, GPs had to modify their practices quickly and constantly adapt their local organization as they received multiple conflicting and late information from the health authorities.

GPs suffered from a health policy considered as too hospital-based. This pre-existing lack of communication and collaboration between GPs and hospitals was revealed by the pandemic [25]. To assist GPs and minimize their likelihood of stress in a health crisis, it might be beneficial to improve their level of information. Health authorities and the media are playing a crucial role in crisis situations and effective communication strategies have shown to improve the dissemination of accurate and appropriate information [26, 27]. As highlighted by Desborough J et al., our results urge that a single source of reliable information from health authorities is needed in time of crisis, both for clinicians and the public [28].

As we conducted our study in real-time, GPs were questioned at the heart of the first pandemic wave and during the lockdown in France. This timing means that GPs answers might have been more spontaneous and closer to their feelings about the health crisis. It also biased the analysis of the determinant of stress, as no baseline evaluation was available. In France, women are more representative of the young generation of GPs [29]. As the census was held online, the young generation was likely to be prompt for answer [30]. It could explain the biased selection of women in our study. Women appeared more stressed, which could increase the mean PSS-10 score. But this trend is well known and described for the PSS-10 score [31]. We used the PSS-10 score, as it has the advantage of being short and quick to fill, while it provides a quantitative measurement of the subjective dimension of stress. Some studies prefer other tools, often associated, to explore different dimensions of well-being, of which we inspired to construct our agreement items [32, 33]. In this particular context, some stress scales have been created to better understand and specifically assess COVID-19-related distress [34]. But those stress scales were validated after the beginning of our study [34]. In our study, while quantitative analysis revealed several causes of stress, many may remain unknown, as underlined by the analysis of verbatims. Qualitative studies are needed to address this issue.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic was very stressful for GPs at the time of the first wave, during the lockdown. A structured and non-controversial chain of communication from the health authorities is important to ensure GP’s confidence. The pandemic underlines the importance of GPs and the liberal network in a health crisis, to provide an ambulatory follow-up of patients with continuity of care. It is therefore crucial to fully integrate GPs in the management and decision process of a health crisis. Links with local hospitals should be developed. A prospective follow-up of GP’s stress during the different phases of the epidemic is needed to strengthen the identification of stress determinants and their evolution.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used to conduct the analysis are not deposited in a public repository. They can be made available to academic researchers upon request to the study scientific committee. Requests have to be addressed to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- AS:

-

Agreement Score

- GP:

-

General Practitioners

- OR:

-

Odds Ratio

- COREB:

-

Operational Coordination of Epidemic and Biological Risks

- PSS:

-

Perceived Stress Score

- URPS:

-

Union Régionale des Professionnels de Santé

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Wu Z, JM MG. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020; Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2762130.

Secrétariat Général de la Défense Nationale. Plan national de prevention et de lutte “Pandémie grippale”; 2009. [cited 2020 Sep 14]. Available from: https://www.gouvernement.fr/sites/default/files/risques/pdf/plan_pandemie_grippale_2011.pdf?fbclid=IwAR1nSUyENGAmVtcN3VNszSlRTUksvjSTTsBihFX2pxMB0C9VlyQfI9v3Y_U

Coignard-Biehler H, Rapp C, Chapplain JM, Hoen B, Che D, Berthelot P, et al. The French infectious diseases Society’s readiness and response to epidemic or biological risk–the current situation following the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus and Ebola virus disease alerts. Med Mal Infect. 2018;48(2):95–102.

Hirsch M, Carli P, Nizard R, Riou B, Baroudjian B, Baubet T, et al. The medical response to multisite terrorist attacks in Paris. Lancet. 2015;386(10012):2535–8.

Taghrir MH, Akbarialiabad H, Ahmadi MM. Efficacy of mass quarantine as leverage of health system governance during COVID-19 outbreak: a mini policy review. Arch Iran Med. 2020;23(4):265–7.

Barbisch D, Koenig KL, Shih F-Y. Is there a case for quarantine? Perspectives from SARS to Ebola. Disaster Med Public Health Prepared. 2015;9(5):547–53.

Bidar B, Charestan P, Cohn E, Dean J-M, Philippe J-M, Pluvinage B, et al. Préparation au risque épidémique COVID – 19 - Fédération Hospitalière de France (FHF); 2020. Available from: https://www.fhf.fr/Offre-de-soins-Qualite/Organisation-de-l-offre-de-soins/Coronavirus-Guide-methodologique-de-preparation-au-risque-epidemique-COVID-19

Ranney ML, Griffeth V, Jha AK. Critical supply shortages — the need for ventilators and personal protective equipment during the Covid-19 pandemic. New Eng J Med. 2020; [cited 2020 Dec 17]; Available from: https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMp2006141.

Mental health and psychosocial considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/WHO-2019-nCoV-MentalHealth-2020.1

Danis K, Epaulard O, Bénet T, Gaymard A, Campoy S, Botelho-Nevers E, et al. Cluster of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the French Alps, February 2020. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(15):825–32.

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–96.

Bellinghausen L, Collange J, Botella M, Emery J-L, Albert É. Validation factorielle de l’échelle française de stress perçu en milieu professionnel. Sante Publique. 2009;21(4):365–73.

Gollac M, Bodier M. Mesurer les facteurs psychosociaux de risque au travail pour les maîtriser - rapport du collège d’expertise Sur le suivi des risques psychosociaux au travail, faisant suite à la demande du ministre du travail, de l’emploi et de la santé; 2011.

Nørøxe KB, Pedersen AF, Bro F, Vedsted P. Mental well-being and job satisfaction among general practitioners: a nationwide cross-sectional survey in Denmark. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19:1 Available from: https://bmcfampract.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12875-018-0809-3.

European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. Psychosocial risks in Europe: prevalence and strategies for prevention: executive summary. Luxembourg: Publications Office; 2014.

CNOM. La santé des médecins: un enjeu majeur de santé publique. Le bulletin de l’Ordre national des médecins. 2017;52:4–5.

Huang Y, Zhao N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 epidemic in China: a web-based cross-sectional survey. medRxiv. 2020;288:112954.

Bohlken J, Schömig F, Lemke MR, Pumberger M, Riedel-Heller SG. COVID-19 pandemic: stress experience of healthcare workers - a short current review. Psychiatr Prax. 2020;47(4):190–7.

Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–20.

Monziols, M.. Comment les médecins généralistes ont-ils exercé leur activité pendant le confinement lié au Covid-19 ? - Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé. 2020 May [cited 2020 Sep 14];(n 1150). Available from: https://drees.solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/etudes-et-statistiques/publications/etudes-et-resultats/article/comment-les-medecins-generalistes-ont-ils-exerce-leur-activite-pendant-le-12120

Use of primary care during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Health Foundation. [cited 2020 Dec 7]. Available from: https://www.health.org.uk/news-and-comment/charts-and-infographics/use-of-primary-care-during-the-covid-19-pandemic

Fineberg HV. Pandemic preparedness and response--lessons from the H1N1 influenza of 2009. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(14):1335–42.

Beaumont M, Duggal HV, Mahmood H, Olowokure B. A survey of the preparedness for an influenza pandemic of general practitioners in the west midlands, UK. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;26(11):819–23.

Patel MS, Phillips CB, Pearce C, Kljakovic M, Dugdale P, Glasgow N. General practice and pandemic influenza: a framework for planning and comparison of plans in five countries. PLoS One. 2008;3(5):e2269.

Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831–41.

Lowrey W, Evans W, Gower KK, Robinson JA, Ginter PM, McCormick LC, et al. Effective media communication of disasters: pressing problems and recommendations. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:97.

Hackman MZ, Johnson CE. Leadership: a communication perspective, sixth edition. Waveland press; 2013. p. 545.

Desborough J, Dykgraaf SH, de Toca L, Davis S, Roberts L, Kelaher C, et al. Australia’s national COVID-19 primary care response. Med J Australia. 2020;213(3):104–106.e1.

La démographie des médecins (RPPS) - Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé. [cited 2020 Sep 23]. Available from: https://drees.solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/etudes-et-statistiques/open-data/professions-de-sante-et-du-social/la-demographie-des-professionnels-de-sante/la-demographie-des-medecins-rpps/

Vinceneux K. Mode de collecte et questionnaire, quels impacts Sur les indicateurs européens de l’enquête Emploi? vol. 69; 2018.

Cohen S. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States; 1988. [cited 2020 Sep 14]. Available from: /paper/Perceived-stress-in-a-probability-sample-of-the-Cohen/049f44c5e6a7e3cfc5621e5e9ead6483573b7ab5

Ozamiz-Etxebarria N, Dosil-Santamaria M, Picaza-Gorrochategui M, Idoiaga-Mondragon N, Ozamiz-Etxebarria N, Dosil-Santamaria M, et al. Stress, anxiety, and depression levels in the initial stage of the COVID-19 outbreak in a population sample in the northern Spain. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 2020;36:4 Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S0102-311X2020000405013&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en.

Elrefaey SRI. Stress, anxiety, and depression symptoms in a population sample in the initial stage of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic outbreak. Evid-Based Nurs Res. 2020;2(3):9.

Taylor S, Landry CA, Paluszek MM, Fergus TA, McKay D, Asmundson GJG. Development and initial validation of the COVID stress scales. J Anxiety Disord. 2020;72:102232.

Acknowledgements

We thank the GIDE company which programmed free of cost the electronic platform for data collection. We thank the URPS which sent this online questionnaire.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed substantially to the design of the study. MD and AK conducted the survey with the assistance of TD, CJ and EP. SM, HC and SLA contributed their expertise to the questionnaire’s construction and study design. MD and AK wrote the draft of the article and conducted the analysis of verbatims. MAD performed the statistical analyses in consultation with MD, AK, and TD. All authors had read and approved the final manuscript. The authors would like to thank all the GPs of the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region who took part in this study.

Authors’ information

MD and AK are general practitioners’ residents in Grenoble University. This work is part of their doctoral thesis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study has been conducted according to the Regulation (EU) 2016/678 (General Data Protection Regulation). Ethics approval was not required according French Law.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

English version of the self-questionnaire.

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Topics classification of the open-ended question of the self-questionnaire.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Dutour, M., Kirchhoff, A., Janssen, C. et al. Family medicine practitioners’ stress during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Fam Pract 22, 36 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-021-01382-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-021-01382-3