Abstract

Background

The Electronic Health Record (EHR) is now widely used in clinical encounters. Because its use can negatively impact the physician-patient relationship, several recommendations on the “patient-centered” use of the EHR have been published. However, the impact of training to improve EHR use during clinical encounters is not well known. The aim of this study was to assess the impact of training on residents’ EHR-related communication skills and explore whether they varied according to the content of the consultation.

Methods

We conducted a pre-post intervention study at the Primary Care Division of the Geneva University Hospitals, Switzerland. Residents were invited to attend a 3-month training course that included 2 large group sessions and 2–4 individualized coaching sessions based on videotaped encounters. Outcomes were: 1) residents’ perceptions regarding the use of EHR, measured through a self-administered questionnaire and 2) objective use of the EHR during the first 10 min of patient encounters. Changes in practice were measured pre and post intervention using the Roter interaction analysis system (RIAS) and EHR specific items.

Results

Seventeen out of 27 residents took part in the study. Participants used EHR in about 30% of consultations. After training, they were less likely to consider EHR to be a barrier to the physician-patient relationship, and felt more comfortable using the EHR. After training, participants increased the use of signposting when using the EHR (pre: 0.77, SD 1.69; post: 1.80, SD3.35; p 0.035) and decreased EHR use when psychosocial issues appeared (pre: 24.5% and post: 9.76%, p < 0.001).

Conclusions

This study suggests that training can improve residents’ EHR-related communication skills, especially in situations where patients bring up sensitive psychosocial issues. Future research should focus on patients’ perceptions of the relevance and usefulness of such skills.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The Electronic Health Record (EHR) is now widely used in clinical encounters and its use is promoted by national incentive programs [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. The EHR improves the quality of biomedical data gathering and reduces the number of medical errors [8,9,10,11,12,13]. It also facilitates the sharing of medical information with the patient [14,15,16].

The literature shows that patients and physicians are mainly satisfied with the use of the EHR [13, 17,18,19,20,21]. However, some patients worry about the loss of confidentiality [18, 22] while some physicians express concerns about the negative impact of the EHR use on the physician-patient interaction [23,24,25].

Behavioral changes linked to the use of the EHR include the following: increased time spent with the EHR during the encounter, especially during the first minutes of the encounter [26], increased moments of silence and a decrease in visual interaction between the physician and the patient [13, 27,28,29,30,31]. Such behaviours tend to distract physicians from picking up verbal or non verbal cues expressed by their patients [32]. Indeed, the time spent looking at the computer screen appears to be inversely correlated with physicians’ interest for patient’s psychosocial and emotional discourse [28,29,30].

Based on such observations, experts in medical communication issued several recommendations on the use of the EHR during the encounter in order to stay patient-centered (Table 1) [28, 33, 34]. Recommendations focus on physician’s verbal and nonverbal communication skills especially during the first few minutes of the encounter. Indeed, physician-patient communication at the beginning of the encounter is particularly important as it sets the stage for a good relationship with the patient, and contributes to identifying the patient’s emotional state and concerns, and to establishing a partnership with the patient [35, 36]; the way the EHR is used clearly affects the opening of the encounter [26]. Experts also highlight the importance of shifting away from the computer when patients express sensitive psychosocial issues [33, 34]. Other non communication elements also include physicians’ typing and computer skills, spatial arrangement of the computer and screen, and personal style of EHR use [37,38,39,40].

Experts recommend integration of EHR skills in the undergraduate medical curriculum [41,42,43,44]. However, only a few studies have assessed the impact of training on the use of such recommendations and these report contrasting results. In a control-group study with first year medical students and standardized patients, Morrow and al. showed that a training course involving role-play increased the use of EHR-related communication skills such as introducing oneself before turning towards the computer, introducing the computer in the triadic relationship, alerting the patient verbally when the doctor turns his/her attention to the computer, and sharing visual information on the screen in the intervention group [45]. Reis et al. compared the impact of two different training formats (traditional lecture vs simulation-based) on resident-patient-EHR communication in a primary care training setting. Performances and attitudes improved in both groups. However, the simulation-based group evaluated the training experience more highly than did the traditional lecture group [46]. Han et al. reported a controlled pre-post intervention study in which medical students demonstrated more patient-centered skills than the control group after having attended an online self-study module on how to preserve the patient-centered relationship while using the EHR [47]. Silverman et al. showed that a specific course on ergonomic computer-use helped medical students to use the EHR in a more patient-centered way during clinical encounters with standardized patients [48].

However, these interventional studies rarely involved real patients, assessed only short term effects (2–3 weeks) [27] and did not specifically study the impact of training on EHR use according to the content of the encounter.

The aim of our study was to assess the impact of training on EHR-related communication skills of residents with real patients during the first 10 min of the clinical encounter. We chose to focus on the first 10 min because we have observed that our residents tend to use the EHR mainly at the beginning of the encounter. In particular, we wanted to explore how EHR use changed when patients introduced psychosocial issues.

Method

Design, setting and participants

A pre-post study was conducted at the Primary Care Division of the Geneva University Hospitals, Switzerland between April and September 2013. The Primary Care Division provides approximately 13’000 medical consultations a year (a majority of follow-up consultations for chronically ill patients) to a diverse urban population, and is also a training center for 40 residents who spend 12 to 24 months training in primary care at the end of their general internal medicine residency training (after 2–4 years of hospital training) before moving to independent practice.

EHR implementation

In January 2012, a new electronic health record (EHR) was developed for primary care consultations, and all physicians in the division are now required to document patient encounters using this EHR. This new EHR is located within the hospital electronic health record, and reflects a problem-oriented medical structure [49]. Data can be entered in either free text fields or via pre-structured fields developed based on the French version of the International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC) [50].

Residents’ and patients’ perceptions regarding EHR use

In October 2012, as part of a needs assessment, a group discussion with 12 residents was conducted in order to explore their perceptions and difficulties regarding the use of the EHR during clinical encounters. They perceived several advantages such as rapid access to and visibility of the information documented in EHR for all health providers, facilitated billing and EHR-based drug prescription. They also reported several difficulties such as the need to master typing skills, the possible loss of confidentiality, and a negative impact on physician-patient communication which they described as altered and more distant, with a loss of visual contact. However, a small phone survey conducted by CL among a random sample of 20 patients who regularly attended the clinic for chronic conditions showed that they were not disturbed by the use of EHR (100% of the patients reported that their physician’s use of EHR was beneficial and none was disturbed by such use).

Based on these results, we decided to develop and assess a training program on how to maintain patient-centered communication when using the EHR during clinical encounters. Residents from two clinics of the division, mainly new residents, were invited to take part in the study: the general primary care clinic (n = 21) and the primary care clinic for asylum seekers (n = 6).

Intervention

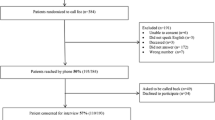

The 3-month training course included two large group sessions and 2–4 individual supervisions based on residents’ own videotaped encounters (Fig. 1). During the first large group session which lasted 90 min, residents were asked to suggest and share strategies considered to be useful for overcoming the difficulties of EHR use during consultations. Based on this discussion and a review of the literature [33, 34], we elaborated nine recommendations for remaining patient-centered while using the EHR during the entire length of clinical encounters, which were subsequently provided to residents (Table 1).

During the next three months, pairs of residents had 2 to 4 1-h coaching sessions under the supervision of a clinical teacher in communication skills (CL, MDD or NJP). Residents were asked to videotape 1–2 new clinical encounters between the coaching sessions (those videos were not analysed for the study). At the beginning of the session, residents were first asked to reflect on their strengths and weaknesses on the basis of the nine recommendations developed during the large group session and provided during the coaching session; they then watched segments of videotaped clinical encounter (a segment chosen by participants or from the beginning, depending on their preferences) and analysed their EHR related behaviors together (the 2 residents and the teacher) ; individual difficulties were addressed through role-play followed by feedback. The focus depended on residents’ needs but often included signposting when using the EHR (telling the patient what you are doing when you shift your attention to the computer) and stopping EHR use when patients expressed emotions or psychosocial issues. Objectives for improvement were identified and documented from one session to the next on a paper portfolio displaying the nine recommendations. The number of sessions varied according to the degree of improvement shown by participants but did not exceed 4.

During the second large group session which took place after three months, the residents involved in the training were asked to share their perceptions and experiences regarding the recommended strategies.

Data collection and outcome measures

Outcomes measures were

-

1)

Residents’ perceptions regarding the use of the EHR before and after the training intervention

Three weeks before and three weeks after the 3-month training period, participants were asked to fill in an 11-item, self-administered questionnaire (5-point Likert scales) about their perceptions regarding the use of the EHR during their clinical encounters (Table 3). This questionnaire was developed based on a review of the literature [23,24,25, 51,52,53,54].

-

2)

Video-based analysis of the clinical encounters

Participants were also asked to videotape 3–4 of their own encounters during a half day three weeks before and three weeks after the training period. Eligible encounters were those conducted in French or English and without the presence of a third person (e.g. family member, interpreter). Before beginning the consultation, participants asked eligible patients to provide a written informed consent to being videotaped during the entire length of the consultation. The analysis was then performed only for the first ten minutes.

Content of the first 10 min of the clinical encounter before and after the training intervention

The content of the physician-patient verbal interaction was coded using the Roter interaction analysis system (RIAS), which is a well-known and validated tool used to capture patterns of verbal communication [55]. The physician and patient interaction was first coded using 7 content categories: 1) medical 2) therapeutic 3) lifestyle 4) psychosocial 5) positive talk 6) emotional talk 7) partnership. Other content codes, such as negative and social talk, were not used due to their minimal presence during clinical encounters. Within each content category and for each speaker, the type of utterance was also coded (closed or open-ended question, information-giving, counseling). Coding was performed by an experienced coder from a Canadian group who developed the French version of the RIAS, using MEDICODE software [56].

Objective use of the EHR during the first 10 min of the clinical encounter before and after the training intervention

The physicians’ use of the EHR was coded using a scale we developed specifically for this study, based on initial observations and analysis of 15 videotaped encounters by the investigators, and a review of the literature [26, 28, 30, 40, 57, 58]. Coded behaviors included: use of signposting (telling the patient what you are doing when you shift your attention to the computer) when using the EHR and use of the keyboard and/or the screen with or without verbal or visual contact with the patient. Contact was coded as present when the physician displayed verbal, non verbal or visual contact with the patient at intervals of less than 5 s. Contact was coded as absent if the physician showed none of these behaviors during periods of 5 s or more (Table 2). This length of time was based on a study showing that pauses of at 5 s or more were more likely to break the conversation and to cause a change in the topic of the conversation [13, 59]. In order to evaluate whether EHR use varied according to the segment of the consultation (opening, history taking, physical examination, explanation/counseling, closing), a sub-sample of videotaped encounters (12 in the pre-intervention and 11 post-intervention) was coded during the entire length of the consultation.

The EHR coding, linked to both the RIAS utterances and to time (in seconds) was performed by DR on an excel file.

Patterns of EHR use

We coded patterns of EHR use as: “low” users (<30% of utterances/time linked to EHR use during the first ten minutes), “medium” users (30–40%) and “high” users (>40% of utterances/time linked to EHR use during the first ten minutes) on the basis of previous research [40].

Intra-rater reliability of RIAS coding, calculated on the basis of 18% videotaped encounters showed 95.5% of stability in utterance cutting and 80.5% of convergence in utterance coding and intraclass correlation coefficient was 0.97. The coder was regularly informed about the convergence rates. The categories for which the rate of disagreement was more than 20% were then discussed with another experienced coder in order to achieve agreement. Since all encounters were coded by the same rater, inter-rater agreement was not an issue in this study. However, a previous study has documented good inter-rater reliability of the RIAS [60].

Inter-rater reliability of EHR coding, calculated on the basis of 10% of the videotaped clinical encounters and performed by CL and NJP, was good (intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.91).

The study was approved by the Geneva University Hospital’s research ethics committee.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics (frequency tables and relative percentages, means, standard deviations) were used to describe the residents’ self-perceptions regarding the training course and its impact on their EHR use, content of physician-patient interaction and the use of EHR during videotaped encounters.

The residents’ self-perceptions about the impact of the training were compared using paired t tests. The frequencies and relative frequencies of the use of EHR were compared using Chi-squared tests. All tests were performed with a significance level of 0.05. All analyses were run on R 2.15.3 (the R Foundation for Statistical Computing), and TIBCO Spotfire S + ® 8.1 for Windows (TIBCO Software Inc).

Results

Seventeen residents (63%) accepted to participate after having been contacted by email: 14 worked in the general primary care clinic and 3 in the primary care clinic for asylum seekers; 10 (59%) were female and mean age was 35 years old (SD 5.2). Five residents (29%) had obtained postgraduate certification in general internal medicine and fourteen (82%) had attended medical school in Switzerland. We did not record reasons for non-participation, but these included reluctance to be videotaped, lack of time/availability or interest.

Residents attended 2.8 (SD 0.57) individualized supervisions; fifteen residents (88%) took part in the first small group session and 9 (53%) in the second session. Reasons for non-attendance included being on vacation, on call or on sick leave.

-

1)

Residents’ perceptions regarding the use of the EHR

Residents generally felt the training helped improve their EHR-related skills and after the training course they were less likely to consider the EHR as a barrier to the physician-patient relationship (Table 3). However, they did not think the training had much impact on more general aspects of the patient-provider relationship (e.g. time dedicated to the patient, interest in their complaints, interruptions of patient talk…).

During the debriefing session, residents described what they learned about maintaining patient-centeredness when using the EHR, including: involving patients when using the EHR, indicating to the patient when using the EHR, documenting key words instead of writing sentences, maintaining contact with the patient during typing phases, and use strategic times to type.

-

2)

Video-based analysis of the clinical encounters

One hundred fourty-two videotaped encounters were analysed (pre-intervention: n = 73 and post-intervention: n = 69).

Content of the first 10 min of the clinical encounter

The content of the first 10 min of the clinical encounter focused mainly on utterrances in the following categories: medical (pre : 17% ; post : 18%), therapeutic (pre : 11% ; post : 13%), positive talk (pre : 22% ; post : 21%) or partnership (pre : 18% ; post : 20%). The lifestyle (pre: 3.5% ; post : 2.7%), psychosocial (pre : 6.6% ; post : 4.2%) and emotional talk (pre : 2.9% ; post : 2.8%) categories occurred less often during the first 10 min of the clinical encounter.

Objective use of the EHR during the first 10 min of the clinical encounter

In general, residents used the EHR about one-third of the utterances/time during the first ten minutes of the clinical encounter both intervention phases (pre: 27.9/26.2%; post: 30.4/28.2%), and used it more during medical and therapeutic talk and less for lifestyle or psychosocial matters (Table 4). EHR use with visual/verbal contact was 4 times more frequent than without visual/verbal contact.

After training, participants increased the use of signposting when using the EHR (Table 4). Although participants increased their use of the EHR after training (Table 4), it occurred only for medical or therapeutic talk (without verbal/visual contact) and positive talk (with verbal/visual contact). The use of the EHR significantly decreased during discussion of psychosocial issues (Table 4). Such changes were observed among different types of users of EHR (low: pre 57 utterances (10.6%) vs post 20 (4.6%) p = 0.01; medium: pre 27 (30.0%) vs post 12 (26.7%) p = 0.01; high: pre 162 (43.2%) vs post 24 (27.0%) p = 0.01).

Analysis of entire consultations confirmed that EHR was used more often during the opening and history taking phases (55 and 66% of the pre- and post-intervention phases) than during the explanation and counseling phases (40 and 32% of the pre- and post-intervention phases).

Patterns of EHR use

Five residents (29.4%) were high EHR users, 5 (29.4%) were medium users and 7 (41, 2%) were low users.

Discussion

Our study shows that before the training intervention, residents used the EHR about 30% of the time/utterances during the initial few minutes of the encounter and more often for medical than for psychosocial topics. They also used the EHR four times more often while maintaining visual/verbal contact.

Significant changes after the intervention included: more signposting of EHR use, increased link with patients while using EHR, more use of EHR related to medical and therapeutic topics and less use associated with psychosocial issues. Residents reported feeling more comfortable using EHR in the consultation, and perceived the EHR as less of a barrier to communication.

Our results confirm those previously published in adult primary care outpatient contexts. Two recent systematic reviews about the impact of the EHR use on the patient-doctor interaction report a mean use of EHR of 32% of the visit time with a range from 12 to 55% with experienced physicians using it less often [13, 27]. Most of the studies (76%) were conducted in adult primary care outpatient clinics but similar results were observed in specialities and in different clinical settings. Very few studies analysed the use of EHR among residents [13, 27]. One study which analysed screen gaze and use of typing among US residents showed increased EHR use (including both screen gaze and typing) among more experienced residents: 43 and 18% respectively among 3rd year residents vs 30 and 9% among 1st year residents. Screen gaze shared by both residents and patients was stable (10%) [61]. To our knowledge, no study analysed EHR use with or without maintaining visual or verbal contact with the patient.

After training, our study participants felt more comfortable using the EHR and were less likely to feel that it interfered with the doctor-patient interaction. These findings are in line with studies conducted in encounters with standardized patients, and support the claim that specific training can improve EHR acceptance among medical students, residents and physicians [46, 48]. This is of importance since physicians are more reluctant than patients to use EHRs and are usually less satisfied than patients when using computers during clinical encounters [13, 27, 62]. The fact that increased EHR use among residents correlates with patient’s dissatisfaction supports the need to train residents on the EHR use in a patient-centered way [61].

The training also impacted on residents’ behaviour by increasing the use of signposting. Transition statements such as “signposting” are known to help the patient understand the structure and the meaning of the consultation, increase his/her participation and implication in the encounter and inform him/her when a new topic is introduced [35, 63, 64]. It is particularly important when using the EHR since the frequency of transitions statements is inversely correlated with the screen gaze [30]. Our results show that signposting, a strategy largely recommended by experts while using the EHR, can be taught effectively [13, 28, 33, 34].

We also found that the training course led to decreased use of the EHR when discussing psychosocial issues with patients, regardless of the resident’s typing style (low, medium or high EHR users). This result is of interest since most experts recommend avoiding computer use when a psychosocial topic is addressed [33, 34].

Why residents increased their use of EHR during both medical and “positive talk” during the first ten minutes of the consultation post training remains unclear. Positive talk includes utterances such as laughter, agreement approvals and compliments and is considered to contribute to build the relationship [55, 65, 66]. Residents may still have difficulties postponing EHR use when biomedical issues are discussed. Residents may also use positive talk to enhance relationship-building while using the EHR. Further research should evaluate whether these changes also occur during the entire length of the encounter.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. We were not able to conduct a controlled or randomized study given the small number of residents who accepted to take part into the study and the pre-post intervention design may threaten the validity of the results given a possible learning effect on use of EHR over time. However, since behavioral changes essentially focused on elements emphasized during training, such changes may be more related to the training than to natural progression over time. The timing and spatial disposition of the videotaping did not allow us to analyse the impact of training for two of the recommendations regarding EHR use: EHR opening was not systematically recorded and the screen position was not always entirely visible on all videotaped encounters. We also made no distinction between visual and verbal contact. Although previous studies have adopted different approaches [30, 67, 68], it is still unclear if verbal contact has the same “value” as visual contact during the physician-patient interaction. The importance of verbal and non verbal communication which has been emphasized by several authors should be further explored when related to EHR use [69, 70]. We did not assess patients’ perceptions regarding the use of EHR, because prior studies have shown that patients were already very satisfied with their physician communication styles and that the introduction of EHRs did not change their satisfaction [17, 21, 62, 71]; given the results of our small phone survey on the use of EHR among chronically ill patients from our clinic, we did not expect to find any difference in patient’s perceptions. We only analysed EHR use during the first ten minutes of the clinical encounter, and we may have missed important EHR related behaviors later in the consultations as well as changing patterns of EHR use. We based our study on the use of one type of EHR program and different EHR programs may yield different EHR behaviors. Finally, the fact that participants themselves asked their patients to participate and knew they were being videotaped may represent a limitation (through selection bias and Hawthorne effect).

Conclusion

Paying attention to both the patient and the computer is challenging and can modify the patient-physician relationship. Given the increasing use of EHRs in health care settings, physicians must find the best way to perform EHR-related tasks without negatively affecting the physician-patient relationship. This study suggests that training can improve residents’ EHR-related communication skills, especially in situations where patients bring up sensitive psychosocial issues. EHR-related communication skills training should be integrated at all stages of medical training given the ongoing development of EHR in the health care system. More research is needed to further explore the EHR-related behaviours that patients expect or value from their doctor, in order to give more scientific evidence to expert recommendations on how and when to use the EHR. It would also be of interest to analyse which factors related to patients, physicians and computers influence the use of EHR during the clinical encounter.

Abbreviations

- EHR:

-

Electronic Health Record

- ICPC:

-

International Classification of Primary Care

- RIAS:

-

Roter interaction analysis system

References

Als AB. The desk-top computer as a magic box: patterns of behaviour connected with the desk-top computer; GPs’ and patients’ perceptions. Fam Pract. 1997;14:17–23.

Schoen C, Osborn R, Squires D, Doty M, Rasmussen P, Pierson R, Applebaum S. A survey of primary care doctors in ten countries shows progress in use of health information technology, less in other areas. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31:2805–16.

Xierali IM, Phillips Jr RL, Green LA, Bazemore AW, Puffer JC. Factors influencing family physician adoption of electronic health records (EHRs). J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26:388–93.

Blumenthal D. Stimulating the Adoption of Health Information Technology. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1477–9.

McConnell H. International efforts in implementing national health information infrastructure and electronic health records. World Hosp Health Serv. 2004;40:33–7. 39–40, 50–52.

Lippert S, Kverneland A. The Danish National Health Informatics Strategy. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2003;95:845–50.

eHealth strategy for Switzerland. Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH). Available at https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/fr/home/themen/strategien-politik/nationale-gesundheitsstrategien/strategie-ehealth-schweiz.html. Accessed 22 May 2017.

Hippisley-Cox J, Pringle M, Cater R, Wynn A, Hammersley V, Coupland C, Hapgood R, Horsfield P, Teasdale S, Johnson C. The electronic patient record in primary care--regression or progression? A cross sectional study. Brit Med J. 2003;326:1439–43.

Kazmi Z. Effects of exam room EHR use on doctor-patient communication: a systematic literature review. Inform Prim Care. 2013;21:30–9.

Sullivan F, Mitchell E. Has general practitioner computing made a difference to patient care? A systematic review of published reports. Brit Med J. 1995;311:848–52.

Burke HB, Sessums LL, Hoang A, Becher DA, Fontelo P, Liu F, Stephens M, Pangaro LN, O’Malley PG, Baxi NS, et al. Electronic health records improve clinical note quality. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015;22:199–205.

Chaudhry B, Wang J, Wu S, Maglione M, Mojica W, Roth E, Morton SC, Shekelle PG. Systematic review: impact of health information technology on quality, efficiency, and costs of medical care. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:742–52.

Crampton NH, Reis S, Shachak A. Computers in the clinical encounter: a scoping review and thematic analysis. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23:654–65.

Sullivan F, Wyatt JC. How computers can help to share understanding with patients. Brit Med J. 2005;331:892–4.

Hersh WR. Medical informatics: improving health care through information. J Am Med Assoc. 2002;288:1955–8.

Arar NH, Wen L, McGrath J, Steinbach R, Pugh JA. Communicating about medications during primary care outpatient visits: the role of electronic medical records. Inform Prim Care. 2005;13:13–22.

Chan W, McGlade K. Patients’ attitudes to GPs’ use of computers. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53:490–1.

Garcia-Sanchez R. The patient’s perspective of computerised records: a questionnaire survey in primary care. Inform Prim Care. 2008;16:93–9.

Garrison GM, Bernard ME, Rasmussen NH. 21st-century health care: the effect of computer use by physicians on patient satisfaction at a family medicine clinic. Fam Med. 2002;34:362–8.

Hsu J, Huang J, Fung V, Robertson N, Jimison H, Frankel R. Health information technology and physician-patient interactions: impact of computers on communication during outpatient primary care visits. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2005;12:474–80.

Irani JS, Middleton JL, Marfatia R, Omana ET, D’Amico F. The use of electronic health records in the exam room and patient satisfaction: a systematic review. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22:553–62.

Ridsdale L, Hudd S. Computers in the consultation: the patient’s view. Br J Gen Pract. 1994;44:367–9.

Doyle RJ, Wang N, Anthony D, Borkan J, Shield RR, Goldman RE. Computers in the examination room and the electronic health record: physicians’ perceived impact on clinical encounters before and after full installation and implementation. Fam Pract. 2012;29:601–8.

Morton ME, Wiedenbeck S. EHR acceptance factors in ambulatory care: a survey of physician perceptions. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2010;7:1c.

Shield RR, Goldman RE, Anthony DA, Wang N, Doyle RJ, Borkan J. Gradual electronic health record implementation: new insights on physician and patient adaptation. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:316–26.

Pearce C, Trumble S, Arnold M, Dwan K, Phillips C. Computers in the new consultation: within the first minute. Fam Pract. 2008;25:202–8.

Alkureishi MA, Lee WW, Lyons M, Press VG, Imam S, Nkansah-Amankra A, Werner D, Arora VM. Impact of Electronic Medical Record Use on the Patient-Doctor Relationship and Communication: A Systematic Review. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:548–60.

Booth N, Robinson P, Kohannejad J. Identification of high-quality consultation practice in primary care: the effects of computer use on doctor-patient rapport. Inform Prim Care. 2004;12:75–83.

Greatbatch D, Heath C, Campion P, Luff P. How do desk-top computers affect the doctor-patient interaction? Fam Pract. 1995;12:32–6.

Margalit RS, Roter D, Dunevant MA, Larson S, Reis S. Electronic medical record use and physician-patient communication: an observational study of Israeli primary care encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;61:134–41.

Warshawsky SS, Pliskin JS, Urkin J, Cohen N, Sharon A, Binztok M, Margolis CZ. Physician Use of a Computerized Medical Record System during the Patient Encounter - a Descriptive Study. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 1994;43:269–73.

Sinsky CA, Beasley JW. Texting while doctoring: a patient safety hazard. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:782–3.

Duke P, Frankel RM, Reis S. How to Integrate the Electronic Health Record and Patient-Centered Communication Into the Medical Visit: A Skills-Based Approach. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25:358–65.

Ventres W, Kooienga S, Marlin R. EHRs in the exam room: tips on patient-centered care. Fam Pract Manag. 2006;13:45–7.

Silverman J, Kurtz S, Draper J. Skills for Communicating With Patients. 3 Revisedth ed. Oxford: Radcliffe Publishing Ltd; 2013.

Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, McWhinney IR, Oates J, Weston WW, Jordan J. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:796–804.

Nemeth LS, Feifer C, Stuart GW, Ornstein SM. Implementing change in primary care practices using electronic medical records: a conceptual framework. Implement Sci. 2008;3:3.

Shachak A, Hadas-Dayagi M, Ziv A, Reis S. Primary care physicians’ use of an electronic medical record system: a cognitive task analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:341–8.

Ventres W, Kooienga S, Marlin R, Vuckovic N, Stewart V. Clinician style and examination room computers: a video ethnography. Fam Med. 2005;37:276–81.

Montague E, Asan O. Physician Interactions with Electronic Health Records in Primary Care. Health Syst (Basingstoke). 2012;1:96–103.

Triola MM, Friedman E, Cimino C, Geyer EM, Wiederhorn J, Mainiero C. Health information technology and the medical school curriculum. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16:54–6.

Lown BA, Rodriguez D. Commentary: Lost in translation? How electronic health records structure communication, relationships, and meaning. Acad Med. 2012;87:392–4.

Tierney MJ, Pageler NM, Kahana M, Pantaleoni JL, Longhurst CA. Medical education in the electronic medical record (EMR) era: benefits, challenges, and future directions. Acad Med. 2013;88:748–52.

Wald HS, George P, Reis SP, Taylor JS. Electronic health record training in undergraduate medical education: bridging theory to practice with curricula for empowering patient- and relationship-centered care in the computerized setting. Acad Med. 2014;89:380–6.

Morrow JB, Dobbie AE, Jenkins C, Long R, Mihalic A, Wagner J. First-year medical students can demonstrate EHR-specific communication skills: a control-group study. Fam Med. 2009;41:28–33.

Reis S, Sagi D, Eisenberg O, Kuchnir Y, Azuri J, Shalev V, Ziv A. The impact of residents’ training in Electronic Medical Record (EMR) use on their competence: Report of a pragmatic trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93:515–21.

Han H, Waters T, Lopp L. Preserving Patient Relationship-centered Care while Utilizing EHRs. MedEdPORTAL Publications. 2014;10:9729.

Silverman H, Ho Y-X, Kaib S, Ellis WD, Moffitt MP, Chen Q, Nian H, Gadd CS. A novel approach to supporting relationship-centered care through electronic health record ergonomic training in preclerkship medical education. Acad Med. 2014;89:1230–4.

Häyrinen K, Saranto K, Nykänen P. Definition, structure, content, use and impacts of electronic health records: a review of the research literature. Int J Med Inform. 2008;77:291–304.

WHO | International Classification of Primary Care, Second edition (ICPC-2). http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/adaptations/icpc2/en/. Accessed 26 May 2016

Rouf E, Whittle J, Lu N, Schwartz MD. Computers in the exam room: differences in physician-patient interaction may be due to physician experience. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:43–8.

Hackl WO, Hoerbst A, Ammenwerth E. “Why the hell do we need electronic health records?”. EHR acceptance among physicians in private practice in Austria: a qualitative study. Methods Inf Med. 2011;50:53–61.

King J, Patel V, Jamoom EW, Furukawa MF. Clinical benefits of electronic health record use: national findings. Health Serv Res. 2014;49:392–404.

El-Kareh R, Gandhi TK, Poon EG, Newmark LP, Ungar J, Lipsitz S, Sequist TD. Trends in Primary Care Clinician Perceptions of a New Electronic Health Record. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:464–8.

Roter D, Larson S. The Roter interaction analysis system (RIAS): utility and flexibility for analysis of medical interactions. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;46:243–51.

Entre les lignes Inc. E, Montreal, Quebec, Canada H4A 3E8. www.ell-research.com. Accessed 22 May 2017.

Asan O, DS P, Montague E. More screen time, less face time - implications for EHR design. J Eval Clin Pract. 2014;20:896–901.

Ventres W, Kooienga S, Vuckovic N, Marlin R, Nygren P, Stewart V. Physicians, patients, and the electronic health record: an ethnographic analysis. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4:124–31.

Newman W, Button G, Cairns P. Pauses in doctor–patient conversation during computer use: The design significance of their durations and accompanying topic changes. Int J Hum Comput Stud. 2010;68:398–409.

Ong LM, Visser MR, Kruyver IP, Bensing JM, van den Brink-Muinen A, Stouthard JM, Lammes FB, de Haes JC. The Roter Interaction Analysis System (RIAS) in oncological consultations: psychometric properties. Psychooncology. 1998;7:387–401.

Asan O, Kushner K, Montague E. Exploring Residents’ Interactions With Electronic Health Records in Primary Care Encounters. Fam Med. 2015;47:722–6.

Gadd CS, Penrod LE. Dichotomy between physicians’ and patients’ attitudes regarding EMR use during outpatient encounters. Proc AMIA Symp. 2000;275–79. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2243374/.

Floyd M, Lang F, Beine KL, McCord E. Evaluating interviewing techniques for the sexual practices history. Use of video trigger tapes to assess patient comfort. Arch Fam Med. 1999;8:218–23.

Levinson W, Roter DL, Mullooly JP, Dull VT, Frankel RM. Physician-patient communication. The relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA. 1997;277:553–9.

Cole SA, Bird J. The Medical Interview: The Three Function Approach. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2013.

Roter DL, Larson S. The Relationship Between Residents’ and Attending Physicians’ Communication During Primary Care Visits: An Illustrative Use of the Roter Interaction Analysis System. Health Commun. 2001;13:33–48.

Asan O, Young HN, Chewning B, Montague E. How physician electronic health record screen sharing affects patient and doctor non-verbal communication in primary care. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98:310–6.

Farber NJ, Liu L, Chen Y, Calvitti A, Street RL, Zuest D, Bell K, Gabuzda M, Gray B, Ashfaq S, et al. EHR use and patient satisfaction: What we learned. J Fam Pract. 2015;64:687–96.

Zoppi K, Epstein RM. Is communication a skill? Communication behaviors and being in relation. Fam Med. 2002;34:319–24.

Ruusuvuori J. Looking means listening: coordinating displays of engagement in doctor-patient interaction. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52:1093–108.

Legler JD, Oates R. Patients’ reactions to physician use of a computerized medical record system during clinical encounters. J Fam Pract. 1993;37:241–4.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Denis Roberge from “Entre les lignes Inc.” for the RIAS coding work.

Funding

The study was supported by a fund of the Faculty of Medicine of the Geneva University (Mimosa)

Availability of data and materials

The datasets during and/or analysed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

CL, MDD, PH, and NJP designed the study. BC, CL, NJP, carried out data analysis. CL and NJP wrote the first version of the article, which was then revised by all the authors. All the authors approved the definitive version of the article.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written Ethical approval was granted by by the Geneva University Hospital’s research ethics committee in March 2013.

Participation was voluntary and participants signed an informed consent form.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Lanier, C., Dominicé Dao, M., Hudelson, P. et al. Learning to use electronic health records: can we stay patient-centered? A pre-post intervention study with family medicine residents. BMC Fam Pract 18, 69 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-017-0640-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-017-0640-2