Abstract

Background

It is common to find a high variability in the accuracy of heart failure (HF) diagnosis in electronic primary care medical records (EMR). Our aims were to ascertain (i) whether the prognosis of HF labelled patients whose ejection fraction (EF) was missing in their EMR differed from those that had it registered, and (ii) the causes contributing to the differences in the availability of EF in EMR.

Methods

Retrospective cohort analyses based on clinical records of HF and attended at 52 primary healthcare centres of Barcelona (Spain). Information of 8376 HF patients aged > 40 years followed during five years was analyzed.

Results

EF was available only in 8.5% of primary care medical records. Cumulate incidence for mortality and hospitalization from 1st January 2009 to 31th December 2012 was 37.6%. The highest rate was found in patients with missing EF (HR 1.84, 95% CI 1.68 -1.95) compared to those with preserved EF. Patients hospitalized the previous year and those requiring home healthcare (HR 1.81, 95% Confidence Interval 1.68-1.95 and HR 1.58, 95% CI 1.46-1.71, respectively) presented a higher risk of having an adverse outcome. Older patients, those more socio-economically disadvantaged, obese, requiring home healthcare, and taking loop diuretics were less likely to have an EF registered.

Conclusions

EF is poorly recorded in primary care. HF patients with EF missing at medical records had the worst prognosis. They tended to be older, socio-economically disadvantaged, and more fragile.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

It is well established that heart failure (HF) symptoms, especially during the early stages, are not specific. This is particularly evident in obese and elderly populations, and in patients suffering from chronic pulmonary diseases [1–3]. Up to 60% of HF patients are not properly diagnosed, and as many as 38% who are HF registered have not had an echocardiogram registered in their medical records [4, 5]. We are unaware of the causes related to this lack of information. Two studies have shown that some General Practitioners did not take in account EF to diagnose HF [6, 7]. It is, therefore, difficult to properly estimate the prognosis and evaluate the efficacy of evidence-based treatment in a large number of HF patients, especially since much of the data comes from clinical trials in which the population has been strictly selected.

Prior hospitalization as a consequence of HF has been considered a valid criterion to confirm diagnosis. Nevertheless, it is possible that gaps exist in sharing information between the hospital and primary care setting which may lead to under registration of HF cases in the primary care Electronic Medical Records (EMR).

Most HF patients, especially the oldest ones and those with multimorbidity, are mainly managed in the primary care setting [8] and, especially those in terminal phases of their disease, are not eligible to be referred to a specialist for an echocardiography.

Regarding the validity of the diagnosis, Schultz et al., argued that if a physician is treating a patient as having HF it is reasonable to consider that this patient is properly labelled HF [9].

Considering the ejection fraction (EF) as a measure to estimate prognosis has proven controversial [10, 11] a recent meta-analysis found lower mortality in HF patients with preserved ejection fraction (HF-PEF) than in those with reduced ejection fraction (HF-REF) [12]. In addition, it has been reported that in patients with unknown EF (i.e. unrecorded) mortality is similar to those with HF-REF and higher in those with HF-PEF [13].

Our study is aimed at analysing the different prognoses of patients registered as HF in primary healthcare records, depending on whether they have HF- REF, HF-PEF, or Possible HF (HF labelled patients with missing ejection fraction), and, if possible, to ascertain the causes contributing to the differences in EF availability in the EMR.

Methods

The present study is a retrospective cohort analysis with four year follow-up. It is based on the clinical information included in the EMR of all HF patients labelled at the 52 primary healthcare centres of the Institut Català de la Salut in Barcelona (Spain).

Clinical information is centralized in the SIDIAP database (Information System for the Development of Research in Primary Care). This database has been shown to be a valid source for cardiovascular disease research [13] and is linked to the Catalan hospital discharge database CMBD-AH (Conjunto Mínimo Básico de Datos de Altas Hospitalarias) [14].

All adult patients >40 years living in Barcelona (Spain), who were labelled HF diagnosis (International Classification Diseases: I.50) registered in their primary EMR on December 31st, 2012, were included.

The registration date of the HF labelling in the EMR was considered as the date of study inclusion. The duration of the study was from the 1st January, 2009 to 31st December, 2012.

Prognosis was determined by hospital admission as a consequence of HF and the global mortality that occurred during the study period.

Event-free time was defined as the period between diagnosis registration and the first hospital admission as a consequence of HF, global mortality, or the last contact with the primary care services.

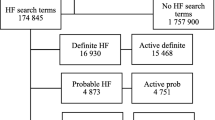

Ejection Fraction: in order to be able to compare our results with previously published studies, HF patients were classified into three categories according to the EF closest to the date of the inclusion: HF-REF (EF < 50%), HF-PEF (EF > = 50%), and Possible HF (when no information, either quantitative or qualitative, about EF was found in the medical records) (Fig. 1).

The following potentially confounding variables at baseline for EF effect were considered: age, gender, hospitalization for HF the year prior to inclusion in the study, smoking habit, cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, obesity), cardiovascular comorbidity (coronary heart disease, atrial fibrillation, stroke, peripheral arterial disease), other comorbidities (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic nephropathy), cardiovascular drug use (antiagregants, lipid lowering drugs, beta-blockers, angiotensin converting-enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, and loop diuretics). We also recorded whether the patients required domiciliary healthcare. Socio-economic levels were measured by the MEDEA index which categorizes populations in quintiles, the first one representing the least disadvantaged. This index is based on several items (unemployment, percentage of manual and temporary workers and persons with insufficient education overall and in young people) [15].

The whole population registered as HF in the primary care EMR in Barcelona (Spain) was included in the analysis, resulting in a sample of 8376 HF patients. These sample reflects the whole population labelled as HF.

In 52 participating primary healthcare centres were registered more than one million subjects. Such a sample size reaches 94% statistical power (estimated power for Cox regression with Wald test; alpha = 0.05 two sides) with a minimum of 30% events observed. It thus ensures enough statistical power to answer the main questions of the study.

Data are expressed as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, and means (standard deviation) for continuous ones. Baseline homogeneity of variables according to the EF was analysed. The one-way ANOVA, and Chi-square tests were used to evaluate differences amongst groups with different or missing EF.

Cumulate incidence of mortality, hospital admission or a combined variable of both events during the follow-up period was estimated for each group (HF-REF, HF-PEF, and Possible HF).

To evaluate the differences among groups according to the time from the inclusion date, Cox regression models crude and adjusted were made. The Hazard Ratio (HR) of each group with respect to the reference was calculated and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were estimated to compare the groups. The models were compiled using the Enter Method, including clinically relevant co-variables and those statistically associated with the previous EF (< or equal to 50%, > 50%, or not available). We evaluated goodness-of-fit and the Cox model’s proportional risk assumption, as well as the interactions at different levels of exposure to each drug, using the Schoenfeld residual analysis. Furthermore, to evaluate the factors related to the probability of having an EF, multivariable logistic regression was performed. For all analyses, a two-tailed p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. IBM-SPSS PC v21 package was used to perform statistical analysis.

Results

From 1st January, 2009 to 31st December 2012, a total of 8376 patients labelled with HF met study criteria,. Median follow-up to event or end of the study was 16.3 months. During the study period, 1608 (19.2%) patients died and 2264 (27.0%) were hospitalized.

Women represented 55.9% of patients and mean age of the population was 78.0 (SD 10.2) years.

Among the sample, 3013 patients (36%) had been admitted to hospital during the year prior to inclusion in the study as a consequence of HF. Ejection fraction was available only in 8.5% of the EMR.

The flow chart represents the distribution of outcomes according to EF (Fig. 1).

By comparing the three categories according to EF, patients in the group with HF-REF were predominantly men (67.0%), had been hospitalized as a consequence of HF the year prior to inclusion in the study (43.8%), and suffered more frequently from coronary heart disease (42.7%). These patients were more often treated with ACE inhibitors and beta-blockers (85.5 and 69.9%, respectively).

Patients with Possible HF were older, required home healthcare, obese, and more frequently treated with loop diuretics. With the exception of coronary disease, no differences were observed in the proportion of patients with atrial fibrillation, stroke history, peripheral artery disease, chronic pulmonary disease, and chronic renal failure according to the EF among the three categories.

The use of ACE inhibitors and beta- blockers was very similar in the group of HF-PEF and Possible HF. The highest proportion of hospitalized or died patients was in the group of Possible HF (39.1%) (Table 1).

Table 2 shows the crude and adjusted hazard ratios for hospitalization or death. Cumulate incidence was 37.6%, and the highest rate was found in patients with Possible HF.

The oldest patients presented 60% more risk (HR: 1.6; CI95%:1.40-1.83) of having an adverse event than the younger ones (≤71 years). Being hospitalized as a consequence of a decompensation the year prior to inclusion almost doubled the risk for re-hospitalization or death (HR: 1.81; CI95%:1.68-1.95). In addition, patients requiring home healthcare had 60% (HR:1.58; CI95:1.46-1.71) more risk than the others of having an adverse event. This risk was also higher among patients living in socio-economically disadvantaged neighborhoods (HR:1.13; CI95%:1.01-1.27).

Hypertension, diabetes, pulmonary and renal diseases, and cardiovascular comorbidity were also associated with a higher risk of having an adverse outcome. Medication for hypercholesterolemia and hypertension, however, worked as protective factors. In contrast, patients taking loop diuretics had a higher rate of adverse outcomes.

Patients hospitalized the year before and without an EF registered in the EMR presented an HR of 4.99, and a 95% Confidence Interval 3.67 to 6.78, for being hospitalized or dying during follow-up.

The adjusted analysis to identify the causes related to the higher probability of missing an EF in the medical records showed that among patients who were elderly, more socio-economically disadvantaged, obese, requiring home healthcare, and taking loop diuretics it was less common to have one registered (Table 3).

Discussion

Our study found that patients labelled with HF who did not have an EF registered in their primary care EMR presented the highest rates of death and hospital re-admissions with respect to those who did. Patients hospitalized as a consequence of HF decompensation the year prior to study inclusion presented a higher probability of having an adverse outcome during follow- up.

The use of administrative databases could be a limitation to properly answer some research questions. The difficulty of having an accurate HF diagnosis registered is well known. Although it has been reported that most HF diagnoses registered in EMR correspond to authentic cases, about one-quarter are not recorded [16].

On the other hand, the use of a large primary care database allows us to have information about the whole population and confers a high external validity. This validity has been previously analyzed and found good for the study of cardiovascular diseases [13]. Although MEDEA deprivation index is not an individual measure but an ecological one, it is useful as a proxy to determine socioeconomic position of the population living in a geographical area.

The MAGGIC study had already reported higher mortality in Possible HF patients, but their proportion of missing EF was lower in our study and some questions were not completely answered, such as socioeconomic position and setting of care (ambulatory or home healthcare, and). In this way we found that patients requiring home care and those in more disadvantaged economic position had a higher probability of not having a EF registered at their EMR.

On the other hand, Possible HF patients had up to 50% more probability of having adverse outcomes than those with HF-REF, and the risk doubled with respect to HF-PEF patients [13].

We have identified several factors which could help explain these findings. Firstly, patients who lacked information about EF were older, as has been reported by other authors in patients attended for acute heart failure at hospital emergency rooms [17]. In our population, the probability for the oldest patients of having an EF recorded in their EMR was less than 50% with respect to the others.

Socio-economic inequality regarding access to specialized care in newly diagnosed HF patients, and a lower probability of undergoing invasive cardiac procedures for the less disadvantaged populations, have been previously described [18, 19]. Nevertheless, most evidence comes from countries with differing healthcare systems where accessibility could vary. In contrast, the Spanish National Health System provides healthcare universal and free. Previous studies performed by our group did not find any inequality regarding therapeutic management in populations suffering from coronary heart disease [20] or at high cardiovascular risk [21, 22].

We, cannot, therefore, satisfactorily account for the fact that the more socio- economically deprived patients showed a lower probability of having an echocardiography performed.

Due to their deteriorated health, patients needing home care are not usually candidates to be referred to undergo tests and explorations, including EF measures. As a consequence, the probability of having an echocardiography is lower than in those with a better life expectancy. Home healthcare is generally oriented towards achieving a better quality of life rather than actually lengthening it. In addition, patients needing this service usually have a very limited quality of life and the hypothetical availability of their EF figures would probably not result in treatment changes. A recent experience in united Kingdom showed that a program of basic cardiac scans (‘Quick scans’) performed in highest risk population could reduce the demand of echocardiography and optimize the detection of structural disease [23].

In agreement with other authors, we found that previous history of HF hospitalization, especially in the previous year, is a powerful predictor for having recurrent events [24–26].

In addition, and again concurring with other publications, we observed that the use of loop diuretics was associated with a higher risk of mortality and hospitalization in HF patients. It has been argued that this effect occurs especially when doses are high and glomerular filtration declines [27].

Conclusions

EF is poorly recorded in primary care. HF patients with EF missing at medical records had the worst prognosis with regard to hospitalisation and survival. They tended to be older, socio-economically disadvantaged, and more fragile.

Abbreviations

- CMBD-AH:

-

Conjunto Mínimo Básico de Datos de Altas Hospitalarias

- EF:

-

Ejection fraction

- EMR:

-

Electronic Medical Record

- HF:

-

Heart failure

- HF-PEF:

-

Heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction

- HF-REF:

-

Heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- SIDIAP:

-

Information System for the Development of Research in Primary Care

References

McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(14):1787–847.

Rutten FH, Moons KG, Cramer MJ, et al. Recognising heart failure in elderly patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in primary care: cross sectional diagnostic study. BMJ. 2005;331(7529):1379.

Daniels LB, Clopton P, Bhalla V, et al. How obesity affects the cut-points for B-type natriuretic peptide in the diagnosis of acute heart failure. Results from the Breathing Not Properly Multinational Study. Am Heart J. 2006;151(5):999–1005.

Otero-Raviña F, Grigorian-Shamagian L, Fransi-Galiana L, et al. Morbidity and mortality among heart failure patients in Galicia, N.W. Spain: the GALICAP Study. Int J Cardiol. 2009;136:56–63.

Hobbs F, Doust J, Mant J, et al. Diagnosis of heart failure in primary care. Heart. 2010;96:1773–7.

Skånér Y, Backlund L, Montgomery H, Bring J, Strender LE. General practitioners' reasoning when considering the diagnosis heart failure: athink-aloud study. BMC Fam Pract. 2005;6(1):4.

Hobbs FD, Jones MI, Allan TF, et al. European survey of primary care physician perceptions on heart failure diagnosis and management (Euro-HF). Eur Heart J. 2000;21:1877–87.

González-Juanatey JR, Alegría Ezquerra E, Bertomeu Martínez V, et al. Insuficiencia cardiaca en consultas ambulatorias: comorbilidades y actuaciones diagnóstico-terapéuticas por diferentes especialistas, Estudio EPISERVE. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2008;61:611–9.

Schultz SE, Rothwell DM, Chen Z, et al. Identifying cases of congestive heart failure from administrative data: a validation study using primary care patient records. Chronic Dis Inj Can. 2013;33(3):160–6.

Owan TE, Hodge DO, Herges RM, et al. Trends prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:251–9.

Bhatia RS, Tu JV, Lee DS, et al. Outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in a population-based study. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:260–9.

Meta-analysis Global Group in Chronic Heart Failure (MAGGIC). The survival of patients with heart failure with preserved or reduced left ventricular ejection fraction: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1750–7.

Poppe KK, Squire IB, Whalley GA, et al. Meta-Analysis Global Group in Chronic Heart Failure. Known and missing left ventricular ejection fraction and survival inpatients with heart failure: a MAGGIC meta-analysis report. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15(11):1220–7.

Ramos R, Balló E, Marrugat J, et al. Validity for use in research on vascular diseases of the SIDIAP(Information System for the Development of Research in Primary Care): the EMMA study. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2012;65(1):29–37.

Available on: http://catsalut.gencat.cat/ca/proveidors-professionals/registres-catalegs/registres/cmdb/

Domínguez-Berjón MF, Borrell C, Cano-Serral G, et al. Constructing a deprivation index based on census data in large Spanish cities (the MEDEA project). Gac Sanit. 2008;22(3):179–87.

McCormick N, Lacaille D, Bhole V, et al. Validity of heart failure diagnoses in administrative databases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e104519.

Cleland JG, McDonagh T, Rigby AS, et al. The national heart failure audit for England and Wales 2008–2009. Heart. 2011;97(11):876–86.

Ehrmann Feldman D, Xiao Y, Bernatsky S, Haggerty J, Leffondré K, Tousignant P, Roy Y, Abrahamowicz M. Consultation with cardiologists for persons with new-onset chronic heart failure: a population-based study. Can J Cardiol. 2009;25(12):690–4.

Hetemaa T, Keskimäki I, Salomaa V, et al. Socioeconomic inequities in invasive cardiac procedures after first myocardial infarction in Finland in 1995. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57(3):301–8.

Munoz MA, Rohlfs I, Masuet S, et al. Analysis of inequalities in secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in a universal coverage health care system. Eur J Public Health. 2006;16(4):361–7.

Mejía-Lancheros C, Estruch R, Martínez-González MA, et al. Socioeconomic status and health inequalities for cardiovascular prevention among elderly Spaniards. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2013;66(10):803–11.

Chambers J, Kabir S, Cajeat E. Detection of heart disease by open access echocardiography: a retrospective analysis of general practice referrals. Br J Gen Pract. 2014;64(619):e105–11.

Senni M, Gavazzi A, Oliva F, et al. In-hospital and 1-year outcomes of acute heart failure patients according to presentation (de novo vs. worsening) and ejection fraction. Results from IN-HF Outcome Registry. Int J Cardiol. 2014;173:163–9.

Khazanie P, Heizer GM, Hasselblad V, et al. Predictors of clinical outcomes in acutedecompensated heart failure: Acute Study of Clinical Effectiveness of Nesiritide in Decompensated Heart Failure outcome models. Am Heart J. 2015;170(2):290–7.

Bello NA, Claggett B, Desai AS, et al. Influence of previous heart failure hospitalization on cardiovascular events in patients with reduced and preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7(4):590–5.

Damman K, Kjekshus J, Wikstrand J, et al. Loop diuretics, renal function and clinical outcome in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18(3):328–3.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the SIDIAP team for their accesibility and help.

Funding

This study has been granted by the Primary Healthcare University Research Institute IDIAP-Jordi Gol.

Avalability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the restrictions by the data owner (IDIAP Research Institute), but could be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

MAM, XM, J R, JLV, EV, MD and JMVR participated in the data management, analysis and interpretation of results, the elaboration and revision of the drafts of the manuscript and in the approval of the final version. CC, EC, and NS participated in the data management, elaboration of the last draft and the approval of the final version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Primary Healthcare University Research Institute IDIAP- Jordi Gol ethics committee (reference number: P13/052). Confidentiality of data was guaranteed in all the process of the study, and data available for research purpose was anonymous. Since the data obtained underwent a double process of anonimization, no interventions were made and the research team had not access to the patient information, ethics committee considered not necessary the patient informed consent. To obtain the access to the database an external scientific committee from IDIAP Jordi Gol assessed and approved the quality and appropriateness of the study protocol, before its submission to the ethics committee. We had permission from our Research Institute (IDIAP Jordi Gol) to accede to the database and publish this manuscript.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Muñoz, MA., Mundet-Tuduri, X., Real, J. et al. Heart failure labelled patients with missing ejection fraction in primary care: prognosis and determinants. BMC Fam Pract 18, 38 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-017-0612-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-017-0612-6