Abstract

Background

Evaluations of diagnostic tests are challenging because of the indirect nature of their impact on patient outcomes. Model-based health economic evaluations of tests allow different types of evidence from various sources to be incorporated and enable cost-effectiveness estimates to be made beyond the duration of available study data. To parameterize a health-economic model fully, all the ways a test impacts on patient health must be quantified, including but not limited to diagnostic test accuracy.

Methods

We assessed all UK NIHR HTA reports published May 2009-July 2015. Reports were included if they evaluated a diagnostic test, included a model-based health economic evaluation and included a systematic review and meta-analysis of test accuracy. From each eligible report we extracted information on the following topics: 1) what evidence aside from test accuracy was searched for and synthesised, 2) which methods were used to synthesise test accuracy evidence and how did the results inform the economic model, 3) how/whether threshold effects were explored, 4) how the potential dependency between multiple tests in a pathway was accounted for, and 5) for evaluations of tests targeted at the primary care setting, how evidence from differing healthcare settings was incorporated.

Results

The bivariate or HSROC model was implemented in 20/22 reports that met all inclusion criteria. Test accuracy data for health economic modelling was obtained from meta-analyses completely in four reports, partially in fourteen reports and not at all in four reports. Only 2/7 reports that used a quantitative test gave clear threshold recommendations. All 22 reports explored the effect of uncertainty in accuracy parameters but most of those that used multiple tests did not allow for dependence between test results. 7/22 tests were potentially suitable for primary care but the majority found limited evidence on test accuracy in primary care settings.

Conclusions

The uptake of appropriate meta-analysis methods for synthesising evidence on diagnostic test accuracy in UK NIHR HTAs has improved in recent years. Future research should focus on other evidence requirements for cost-effectiveness assessment, threshold effects for quantitative tests and the impact of multiple diagnostic tests.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Just like any other intervention or medical device, diagnostic tests require rigorous evaluation before being implemented in clinical practice. Evaluations of diagnostic tests are notoriously complex, however, in part because of the indirect nature of their impact on patient outcomes.

Economic evaluations are now intrinsic to adoption decisions; many guideline bodies will not recommend a test for use in clinical practice without evidence of its cost-effectiveness [1–4]. Model-based health economic evaluations of tests have become increasingly popular as they allow many different types of evidence to be considered and incorporated, as well as enabling estimates of cost-effectiveness to be made beyond the duration of any single study. To facilitate this analysis, evidence should preferably be synthesised from all aspects of the care pathway in which the test is used.

Economic decision models typically require information about test accuracy to estimate the proportion of patients on each care pathway following a particular test outcome, and to weight the associated costs and health outcomes [1]. Test accuracy studies, however, are prone to many types of bias and formulating study designs that produce high quality evidence can be challenging [5]. Additional complexities arise when attempting to synthesise evidence from different test accuracy studies. One statistical complication is that accuracy is typically summarised using two linked, dependent outcomes: sensitivity (the accuracy of the test in patients with the target condition) and specificity (the accuracy of the test in patients without the target condition) [6]. Statistical models which account for these correlated outcomes, such as the bivariate model and the Hierarchical Summary Receiver Operating Characteristic (HSROC) model, are now advocated as best practice [5, 7–9].

In 2009, Novielli et al. conducted a systematic review of UK NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) reports that had carried out economic evaluations of diagnostic tests [10]. They evaluated the methods used to synthesise evidence on test accuracy, specifically, and looked at how these results were subsequently incorporated into economic decision models. Very few of the reports implemented meta-analysis methods that accounted for the correlation between sensitivity and specificity. Since this review, significant work has been carried out to make best practice methods for the meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy more accessible [7, 11, 12].

The authors also highlighted two potential methodological problem areas in their discussion: 1) how thresholds were dealt with in the evaluation of quantitative tests, and 2) how reviews account for the potential dependency in performance for combinations of tests [5]. The first issue relates to tests that produce numerical results which are subsequently categorised into ‘positives’ or ‘negatives’ by selecting a specific threshold. The threshold at which accuracy is reported can differ between primary studies, causing problems when pooling results in a meta-analysis. A lot of work has been carried out in recent years to develop methods to overcome this issue [13–16], but the extent to which they are being used is unclear. The second issue arises when more than one test is being evaluated within a clinical pathway and the performance of one impacts on the other (see [17] for more information).

An additional challenge we encounter frequently is the paucity of diagnostic accuracy evidence from the primary care setting. Conducting diagnostic accuracy research in primary care is challenging due to low disease prevalence, inflating both research time and costs [18]. As a consequence, much of the evidence for tests used in general practice has been acquired in secondary care settings [19]. Although it is well known that the predictive value of a test is dependent on the prevalence of the condition in question, it has only recently been acknowledged that test characteristics such as sensitivity and specificity also vary across clinical settings due to differing spectrums of disease severity [20]. These findings bring to question the transferability of evidence generated in secondary care to primary care.

The main objective here is to review current methods used to synthesise evidence to inform economic decision models in Health Technology Assessments of diagnostic tests. We update Novielli et al.’s original review, but also expand to formally assess the methodological issues outlined.

Methods

Inclusion criteria

We screened all 480 UK NIHR HTA reports published between May 2009 (the end date of the Novielli et al. review [10]) and July 2015 (Volume 19, Issue 52 of the NIHR HTA Journals Library).

In an initial screen, we determined whether each report evaluated an intervention or treatment; evaluated a test or multiple tests; focused on methodological development; or fell into none of these categories (for example, purely observational studies such as [21]). Of those that evaluated at least one test, we classified the primary role of the test as either screening, diagnosis, prognosis, monitoring or treatment selection based on the abstract of the HTA report. The last of these categories, which was not considered by Novielli et al. [10], was included to recognise that the purposes of some HTA reports is to use test results to guide a suitable choice of treatment in a particular patient group; see [22] for an example of a report that falls into this category. The five categories are not mutually exclusive, as some reports have multiple objectives, so for the purposes of our study, precedence was given to the ‘diagnosis’ classification if a report additionally fell into one of the other categories.

We then assessed the full texts of those that evaluated a diagnostic test to identify those that included both a model-based health economic evaluation and a systematic review. Those that carried out a systematic review were categorised further according to whether they conducted a formal meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy results (defined as the statistical pooling of quantitative study outcomes) as part of their systematic review, which was the final criterion for inclusion.

We additionally scrutinised two groups of reports that fell outside our original inclusion criteria. Firstly, we looked at reports of diagnostic tests that conducted a systematic review but did not carry out a meta-analysis, as we were interested in the factors that led the authors of these reports to use results summaries other than meta-analysis. Secondly, we considered prognostic studies that conducted both a health economic evaluation and a meta-analysis, in the expectation that the methodology used for diagnostic studies is often equally applicable in a prognostic setting [23].

Data extraction

A data extraction spreadsheet was developed (a list of all of the information extracted is available in the Additional file 1).

The search criteria from each systematic review was extracted to determine whether the authors specifically looked for evidence on test-related outcomes or patient outcomes, rather than only diagnostic accuracy results, when deciding which studies to include. Test-related outcomes includes items such as test failure rate, time to test result, proportion of inconclusive test results, and interpretability of the test results. Patient outcomes refers to items that capture the downstream consequences of the test for the patient, including clinical decisions in terms of further tests, treatment and management for patients, and associated health service utilization and costs, as well as patient health outcomes such as survival and/or health related quality of life. We also recorded which reviews presented information about test-related outcomes or patient outcomes in their report, whether or not these outcomes had been included in the search criteria. Thus this evidence was classified as ‘systematically searched for’, ‘some evidence reported but not systematically searched for’, or ‘neither systematically searched for nor reported’.

For studies that reported a meta-analysis, we extracted the following key information: 1) the outcomes synthesised, 2) whether a formal quality assessment of the included studies was carried out, 3) the statistical methods used to synthesise test outcomes, and 4) whether these pooled outcomes were included in the subsequent health economic analyses. If a report contained more than one diagnostic test, it was regarded as having included the relevant information if this was reported in any of the tests considered.

For the group of studies that carried out a systematic review but did not present a meta-analysis, we reviewed the methods section of the report to ascertain if a meta-analysis had been planned and, if so, the reasons it was not carried out or not reported.

Apart from the above, we were also particularly interested in three other factors and extracted data on: 1) how threshold effects were explored/analysed in evaluations of tests that produce quantitative results, 2) how evidence from different healthcare settings from the one of interest was handled, and 3) how reviews incorporated information from multiple tests as part of a treatment pathway.

The whole screening and extraction process was carried out independently by two researchers (BS and TRF). If required, disagreements were resolved by an additional researcher (LA or YY).

Results

Search results

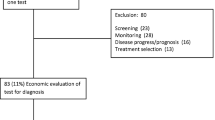

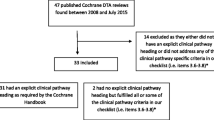

A flowchart of the search results and reasons for inclusions can be found in Fig. 1. Of the 480 UK NIHR HTA reports considered, 110 (23%) evaluated a test, and around half of these (53) were for the purpose of diagnosis. The 18 reports of diagnostic tests that were excluded because they did not include a systematic review tended to include primary research which informed the economic model parameters. A total of 35 reports [24–58] included a health economic evaluation of at least one diagnostic test and a systematic review, and 22 of these [37–58] reported the results of a meta-analysis as part of their systematic review. Additionally, there was a single report of a prognostic test, a study of foetal fibronectin testing to predict pre-term birth [59], that included both an economic evaluation, a systematic review, and a meta-analysis of the accuracy of the prognostic test.

Evidence reviewed in addition to diagnostic accuracy

In addition to diagnostic accuracy outcomes, evidence on test-related outcomes (8/22 reports) [37, 44, 45, 47, 50, 51, 56, 57] and patient outcomes (11/22 reports) [37, 44, 45, 47, 49–51, 54, 56–58] was also explicitly searched for in the systematic reviews. Additionally, four reports presented information about test-related outcomes [40, 52, 53, 55] and four presented information about patient outcomes [39, 52, 53, 55] without these being systematically searched for, according to the search criteria. When available, evidence on test-related outcomes was summarised descriptively. Patient outcome evidence was often not available, or was available from only one or two studies, which were not always randomised trials. Of the fifteen reviews that reported patient outcome data, only three identified sufficient evidence for meta-analysis [44, 49, 53]; the remainder identified no or little evidence, thereby negating the possibility of meta-analysis.

Meta-analysis methods and reporting

Of the 13 reports that carried out a diagnostic accuracy systematic review but did not present a meta-analysis, a meta-analysis had been planned but not carried out in all but two: one of these was an initial scoping exercise [24], and the other presented pooled summary estimates of treatment effectiveness but not the diagnostic test under consideration [36]. Of the other 11, a high level of clinical and/or statistical heterogeneity was the primary explanation most commonly given for not reporting a meta-analysis, although some reported finding insufficient or inadequate data in the primary studies [29, 30, 35] and one cited “the overwhelming positive nature of all of the results regarding the analytical validity of each of the tests” [28].

In all 22 reports meeting the inclusion criteria, the QUADAS or QUADAS2 checklist (depending on the timing of the report) was used to evaluate the quality of the diagnostic accuracy studies included in the reviews [60]. Table 1 shows the statistical methods used to synthesise the evidence on test accuracy and the pooled summary statistics presented following meta-analysis.

The bivariate model or the equivalent HSROC model (including variants that use a Bayesian framework) were implemented for the primary analysis in all but two reports [42, 57]. Many of these reports had to resort to statistical models that do not account for the correlation between sensitivity and specificity (e.g. fitting two separate random or fixed effects logistic regressions for sensitivity and specificity, setting the correlation parameter to zero in the bivariate model) for some secondary meta-analyses due to the small number of studies or convergence issues.

Forest plots depicting the between-study heterogeneity of sensitivity and specificity estimates were presented in 16 of the 22 reports, and estimates from contributing studies were displayed in ROC space (with or without an overlaid fitted summary ROC curve) in 18 reports. Other less common graphical methods used include Fagan’s nomogram for likelihood ratios [55], a plot to show the change in sensitivity and specificity according to changes in the quantitative threshold [44], and a graph of pre-test against post-test probabilities [48]. Formal quantification of heterogeneity using I2 or the chi-squared test was presented in 11 reports.

A wide variety of software was used to carry out the meta-analyses, Stata (in particular, the glamm and metandi functions [11]) being the most popular (used in 11/22 studies). Other software packages used include MetaDiSc, R (the now defunct diagmeta package), Review Manager, SAS (the METADAS and NLMIXED macros) and WinBUGS.

Summary of other outcomes

Investigation of Threshold Effects

Seven of the 22 reports evaluated at least one diagnostic test that produced fully quantitative results [38, 40, 43, 44, 52, 55, 58]. Additionally, one report used an individual participant data (IPD) meta-analysis [48] which, by its nature, allows a range of quantitative thresholds to be considered and which is discussed separately below. Two other reports used a test that was partially quantitative, in the sense that the diagnostic decision was based on both quantitative and qualitative information, but the final decision could not be expressed based simply on a numerical score or measurement [37, 42].

Accuracy was reported at differing thresholds across primary studies within each of the seven diagnostic reports that evaluated quantitative tests. Five of these reports found at least one study in their systematic review that reported diagnostic accuracy at more than one threshold. All but one of these reports [43] showed a summary ROC curve to depict how accuracy varied at different thresholds. Six attempted to quantify threshold effects – the tendency of diagnostic performance to vary according to the threshold used to define test positivity – but only two [44, 55] were able to provide unambiguous recommendations about the threshold practitioners should use. Even among these, one [55] was hindered by limited primary evidence about the performance of faecal calprotectin for the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease at thresholds other than 50 μg/g, and in the other [44] the authors were able to investigate threshold effects for only one (the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale) of the 14 measures considered for the identification of postnatal depression in primary care.

The single relevant report that considered a prognostic score found that all primary studies in the systematic review that reported the threshold used the same standard foetal fibronectin value of above 50 ng/ml to define a positive test result.

Individual patient data (IPD) meta-analysis

In one report [48], which looked at patient signs and symptoms as factors in the diagnosis of heart failure, the authors wanted to explore the diagnostic potential of several variables simultaneously, with the restriction that variables were required to be obtainable in a general practice setting. In many scenarios, the performance of diagnostic tests are reported on a ‘per variable’ basis, without any attempt to perform multivariable adjustment or create a combined diagnostic score. In contrast, several previous heart failure diagnostic and prognostic models had previously been developed [61], some of which found widespread use, although the large number of variables required to be collected means that not all are suitable for primary care.

To overcome this issue, the authors obtained full patient-level data from nine of the primary cohorts that they had identified in their systematic review. They then used these in an IPD meta-analysis to create a series of seven new candidate diagnostic scores using logistic regression modelling, although the presence of heterogeneity meant that data from only one of the primary studies were used to develop the model; data from the other studies were used for validation. The IPD allowed the authors not only to develop the diagnostic models, but also to test the resulting scores were adequately calibrated and to investigate the effect of changing the threshold for test positivity on diagnostic performance, with a view to creating a usable set of decision rules suitable for general practice. Results are presented in terms of pre-test and post-test probabilities of heart failure.

Health care setting

The report of Mant et al. was one of only three [44, 45, 48] in our final sample that aimed unambiguously to assess a diagnostic test for use in primary care or as a point-of-care test, and was also unusual in that its IPD analysis specified a primary care setting as an inclusion criteria. Four other reports [40, 41, 53, 55] considered tests that were potentially usable or primary care, or which might be used across different health settings.

These reports did not restrict their search to studies conducted in primary care, and did not distinguish between setting when conducting the meta-analysis. Indeed, for most of these reports, few or no studies based in a primary care setting were found and so the authors were unable to assess whether test accuracy was the same in primary and secondary care. For example, the faecal calprotectin report of Waugh et al. [55] specifically recommends studies in primary care populations as a future research need. Similarly, Drobniewski et al. [41] discuss the need for further research in targeted patient populations for the use of molecular tests for antibiotic resistance in tuberculosis as point-of-care tests; the majority of primary studies included in that report were conducted in a laboratory environment.

Health economic modelling

In extracting information about the types of health economic decision analytic models implemented, we found that the methodology was often described using differing terminology and reported in varying level of detail. The two most common classes of models adopted were decision trees and Markov models, although the precise form of the model varied, and other model formulations guided by the healthcare context (e.g. [43, 47, 55]) were also used.

The extent to which the results of the test accuracy meta-analyses informed the model parameters in the cost-effectiveness analyses was evaluated. Four of the test accuracy meta-analyses, including the one IPD meta-analysis [48], provided all of the accuracy data required for the cost-effectiveness modelling [38, 44, 48, 58]. In fourteen reports, some of the accuracy parameters had to be informed by single studies, expert opinion, or assumptions [39–41, 43, 45–47, 50–53, 55–57], including one in which the results of the meta-analysis had to be adjusted to account for the fact that the reference standard used was not 100% accurate [46]. In four reports, the results of the diagnostic accuracy meta-analysis were not used to inform the cost-effectiveness analyses. Instead, accuracy model parameters were either extracted from single studies [37, 54] or elicited from clinicians [49], or based on a combination of these [42].

In all 22 of the reports, some attempt was made to explore the effect of uncertainty in the accuracy estimates, typically via one-way (univariate), extreme case or, more commonly, probabilistic sensitivity analysis.

Of the seven reports that evaluated the cost-effectiveness of a fully quantitative test, the majority (6/7) explored how differing the threshold impacted on the cost-effectiveness of the test. This was, however, restricted to the few thresholds at which sufficient data was available for meta-analysis or a sub-group analysis. In contrast, threshold was included as a full parameter in the cost-effectiveness model where IPD was available and ‘optimised’ against willingness to pay [48].

Multiple tests within the diagnostic pathway

The majority of reports (16/22) considered the effect of a combination of tests within the diagnostic pathway into their decision model. This includes both scenarios in which a new test is being added to an existing one, possibly at a different point in the pathway and those in which multiple tests are evaluated concurrently. Most of these reports did not discuss the issue of possible dependence between multiple tests being evaluated on the same individual, or made an explicit assumption that the tests were being regarded as independent, calculating required joint probabilities via Bayes rule (e.g. [53]). Two reports tested the assumption of independence in a sensitivity analysis [46, 52].

Discussion

This review assesses current methods used to synthesise evidence to inform economic decision models in Health Technology Assessments of diagnostic tests.

In six years of UK NIHR HTA reports published since 2009, there has been a notable improvement in the quality of meta-analytic methods used by authors. During the period 1997-May 2009, only two of fourteen reports used the bivariate or the HSROC model for meta-analysing diagnostic accuracy data across studies [10]. In the subsequent period, to July 2015, this figure rose to 20 out of 22. Our conclusion is that during the last six years, these methods are now routinely accepted as standard practice within UK NIHR HTAs. Priority areas for methodological improvement within future UK NIHR HTAs of diagnostic tests are outlined below.

Priority area 1: Evidence requirements for cost-effectiveness evaluations of tests

Most reports focused their systematic reviews on test accuracy. Many did look for other outcomes at the same time, but not all. It was difficult to formally assess whether each systematic review had looked for evidence on all the necessary outcomes to inform the cost-effectiveness model as there is poor agreement on what evidence is required to inform adoption decisions for tests, and the evidence required is likely to depend heavily on the context. One systematic review identified 19 different ‘phased evaluation schemes’ for medical tests [62].

Nevertheless, the distinct lack of evidence identified on the impact of a test on patient outcomes was notable. Randomised controlled trials in this setting are often impractical due to long follow-up periods required to capture downstream patient outcomes, large sample sizes and the speed at which technology is advancing in this area (see [63] for further discussion on this topic). Often the technology has developed or changed by the time the trial is complete [64]. To overcome this issue, some studies have used a linked evidence approach (e.g. [65]) and carried out two separate reviews – one looking at outcomes related to the test and another focusing on the impact of therapeutic changes on morbidity, mortality and adverse effects.

There currently lacks a clear framework that describes the evidence required for cost-effectiveness evaluations of tests. For the time being, we would recommend that authors use this checklist [66] to identify outcomes potentially relevant to their research question and tailor their systematic literature searches accordingly. The same rigour implemented for the systematic searches for test accuracy evidence should also be applied for other outcomes, if the objective is to evaluate the diagnostic pathway holistically.

Priority area 2: The evaluation of threshold effects in quantitative tests

Ideally, thresholds should be selected that balance the repercussions of a false negative and false positive result in terms of patient outcomes and costs. The accuracy of a diagnostic test is typically evaluated by calculating paired summary statistics from a 2 × 2 classification table (e.g. sensitivity and specificity). Even for quantitative tests, clinical application often involves the selection of a single threshold to guide treatment decisions, and therefore accuracy needs to be summarised at this threshold. Perhaps for this reason, primary diagnostic accuracy often report accuracy measures at just one threshold, which can limit the opportunity to pool accuracy at all thresholds and make comparisons between them in a meta-analysis.

Of the seven (non-IPD) reports that evaluated quantitative tests, the authors were able to make clear optimal threshold recommendations in only two. In the one report that carried out an IPD meta-analysis [48], diagnostic accuracy was pooled across the whole test scale, allowing it to be incorporated as a parameter that could be optimised when fitting the cost-effectiveness model. The authors were thus able to identify and recommend the threshold which provided optimal clinical- and cost-effectiveness. The issue of threshold selection is likely to be of particular importance when assessing whether test accuracy is transferrable between different settings, such as from secondary to primary care, as health settings may differ in their patient populations and in the level of accuracy that is required for the test to be adopted.

Statistical methods have been proposed to overcome this issue [13–16], but they are generally only possible to implement if accuracy is reported at multiple thresholds within a single study, or at a broad range of thresholds across different studies. We recommend where possible that 2 × 2 data is obtained across all thresholds from each study to allow accuracy to be summarised across the whole test scale and thus available as a parameter for subsequent cost-effectiveness analyses. Alternatively, researchers might consider making entire data files available for future evidence synthesis via IPD analysis, a practice which is already encouraged or required by some journals.

Priority area 3: The evaluation of test combinations within the diagnostic pathway

Many treatment pathways rely on results from multiple diagnostic tests, either performed in parallel or in sequence. Our results show that the majority of UK NIHR HTA reports that consider test combinations treat them as independent. The few that do consider the dependence caused by performing two or more tests on the same individual are often restricted by a lack of evidence about the extent of the dependence from primary studies.

We suggest two possible strategies for dealing with this issue in future diagnostic treatment evaluations. The first, and simplest, is to conduct sensitivity analysis assuming different quantitative estimates of within-individual correlation between test results [46, 52]. The second is to conduct primary studies, including randomised trials, which consider the entire treatment pathway as the intervention, rather than only a single component. This approach, although considered by some of the reports in our review (e.g. [50]), is likely to be costly and may be difficult to evaluate if the patient pathway is complex. At a minimum, authors of primary studies should consider reporting information about between-test correlation or making IPD data available. Additionally, although some methodological work has been conducted in this area [67], further research would be valuable.

Limitations

By including a systematic review as one of the requisites for inclusion in this review, 7 reports that evaluated at least one diagnostic test were excluded from this review. Of these, 6 were based on primary studies conducted as part of the UK NIHR HTA grant (5 randomised trials [68–72] and 1 diagnostic accuracy study [73]) and a further report based their evaluation on a sub-study of an existing trial [74].

Conclusions

The results of this review demonstrate that, within UK NIHR HTAs, diagnostic accuracy meta-analyses are now routinely conducted using statistically appropriate methods that account for the nuances and challenges unique to diagnostic accuracy research.

Despite this commendable progress, there is still room for improvement in the methodology applied within HTAs. There is generally a gap in understanding the evidence requirements to inform cost-effectiveness analyses of diagnostic tests. More specifically, the evaluation of quantitative tests remains a challenge due to incomplete reporting of accuracy across thresholds. Greater efforts are also required to ensure that potential dependencies in test performance are accounted for when tests are used sequentially within a diagnostic pathway.

Abbreviations

- HSROC:

-

Hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristic

- HTA:

-

Heath technology assessment

- IPD:

-

Individual patient data

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic.

References

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, Diagnostics Assessment Programme Manual. Manchester: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2011.

Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Available from: https://www.cadth.ca/. Accessed 23 Mar 2017.

Health, A.G.D.o. Health Technology Assessment. Available from: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/hta/publishing.nsf/Content/home-1. Accessed 23 Mar 2017.

Scotland, N. Scottish Medicines Consortium. Available from: https://www.scottishmedicines.org.uk/. Accessed 23 Mar 2017.

Leeflang MM, et al. Systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(12):889–97.

Mallett S, et al. Systematic reviews of diagnostic tests in cancer: review of methods and reporting. BMJ. 2006;333(7565):413.

Macaskill P. Chapter 10: Analysing and Presenting Results. In: Deeks J, Bossuyt P, Gatsonis C, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Version 1.0. London: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2010.

Leeflang MM. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of diagnostic test accuracy. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(2):105–13.

Campbell JM, et al. Diagnostic test accuracy: methods for systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):154–62.

Novielli N, et al. How is evidence on test performance synthesized for economic decision models of diagnostic tests? A systematic appraisal of Health Technology Assessments in the UK since 1997. Value Health. 2010;13(8):952–7.

Harbord RM, Whiting P. metandi: Meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy using hierarchical logistic regression. Stata J. 2009;9(2):211.

Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A, Pickles A. GLLAMM Manual, in U.C. Berkeley Division of Biostatistics Working Paper Series. CA: UC Berkley; 2004.

Dukic V, Gatsonis C. Meta-analysis of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Assessment Studies with Varying Number of Thresholds. Biometrics. 2003;59(4):936–46.

Riley RD, Takwoingi Y, Trikalinos T, Guha A, Biswas A, Ensor J, Morris RK, Deeks JJ. Meta-analysis of test accuracy studies with multiple and missing thresholds: a multivariate-normal model. Journal of Biometrics & Biostatistics. 2014:5(3):1.

Hamza TH. Multivariate random effects meta-analysis of diagnostic tests with multiple thresholds. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9(1):1.

Steinhauser S, Schumacher M, Rucker G. Modelling multiple thresholds in meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16(1):97.

Novielli N, Sutton AJ, Cooper NJ. Meta-analysis of the accuracy of two diagnostic tests used in combination: application to the ddimer test and the wells score for the diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis. Value Health. 2013;16(4):619–28.

Green C, Holden J. Diagnostic uncertainty in general practice. A unique opportunity for research? Eur J Gen Pract. 2003;9(1):13–5.

McCowan C, Fahey T. Diagnosis and diagnostic testing in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56(526):323–4.

Leeflang MM. Bias in sensitivity and specificity caused by data-driven selection of optimal cutoff values: mechanisms, magnitude, and solutions. Clin Chem. 2008;54(4):729–37.

Eames K. The impact of illness and the impact of school closure on social contact patterns. Health Technol Assess. 2010;14(34):267–312.

Czoski-Murray C. What is the value of routinely testing full blood count, electrolytes and urea, and pulmonary function tests before elective surgery in patients with no apparent clinical indication and in subgroups of patients with common comorbidities: a systematic review of the clinical and cost-effective literature. Health Technol Assess. 2013;16(50):159.

Collins GS. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD Statement. BMC Med. 2015;13(1):1–10.

Beale S. A scoping study to explore the cost-effectiveness of next-generation sequencing compared with traditional genetic testing for the diagnosis of learning disabilities in children. Health Technol Assess. 2015;19(46):128.

Beynon R. The diagnostic utility and cost-effectiveness of selective nerve root blocks in patients considered for lumbar decompression surgery: a systematic review and economic model. Health Technol Assess. 2013;17(19):88.

Bryant J. Diagnostic strategies using DNA testing for hereditary haemochromatosis in at-risk populations: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13(23):148.

Burch J. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of technologies used to visualise the seizure focus in people with refractory epilepsy being considered for surgery: a systematic review and decision-analytical model. Health Technol Assess. 2012;16(34):163.

Fleeman N. The clinical and cost effectiveness of testing for cytochrome P450 polymorphisms in patients treated with antipsychotics: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2010;14(3):182.

Rodgers M. Colour vision testing for diabetic retinopathy: a systematic review of diagnostic accuracy and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13(60):160.

Sharma P. Elucigene FH20 and LIPOchip for the diagnosis of familial hypercholesterolaemia: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2012;16(17):265.

Simpson, E.L. Echocardiography in newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation patients: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technology Assessment, 2013. 17(36).

Snowsill, T. A systematic review and economic evaluation of diagnostic strategies for Lynch syndrome. Health Technol Assess, 2014. 18(58).

Stevenson M. Non-invasive diagnostic assessment tools for the detection of liver fibrosis in patients with suspected alcohol-related liver disease: A systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2012;16(4):174.

Wade R. Adjunctive colposcopy technologies for examination of the uterine cervix - DySIS, LuViva Advanced Cervical Scan and Niris Imaging System: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2013;17(8):240.

Westwood, M. Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase (EGFR-TK) mutation testing in adults with locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Technol Assess, 2014. 18(32).

Whiting, P. Viscoelastic point-of-care testing to assist with the diagnosis, management and monitoring of haemostasis: a systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Technol Assess, 2015. 19(58).

Brush J. The value of FDG positron emission tomography/ computerised tomography (PET/CT) in pre-operative staging of colorectal cancer: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2011;15(35):192.

Campbell, F. Systematic review and modelling of the cost-effectiveness of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging compared with current existing testing pathways in ischaemic cardiomyopathy. Health Technol Assess, 2014. 18(59).

Cooper KL. Positron emission tomography (PET) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for the assessment of axillary lymph node metastases in early breast cancer: systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2011;15(4):134.

Crossan, C. Cost-effectiveness of non-invasive methods for assessment and monitoring of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic liver disease: systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess, 2015. 19(9).

Drobniewski, F. Systematic review, meta-analysis and economic modelling of molecular diagnostic tests for antibiotic resistance in tuberculosis. Health Technol Assess, 2015. 19(34).

Fortnum H. The role of magnetic resonance imaging in the identification of suspected acoustic neuroma: a systematic review of clinical and cost effectiveness and natural history. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13(18):176.

Goodacre S. Systematic review, meta-analysis and economic modelling of diagnostic strategies for suspected acute coronary syndrome. Health Technol Assess. 2013;17(1):177.

Hewitt C. Methods to identify postnatal depression in primary care: an integrated evidence synthesis and value of information analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13(36):230.

Hislop J. Systematic review of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of rapid point-of-care tests for the detection of genital chlamydia infection in women and men. Health Technol Assess. 2010;14(29):125.

Holmes, M. Routine echocardiography in the management of stroke and transient ischaemic attack: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess, 2014. 18(16).

Huxley, N. A systematic review and economic evaluation of intraoperative tests [RD-100i one-step nucleic acid amplification (OSNA) system and Metasin test] for detecting sentinel lymph node metastases in breast cancer. Health Technol Assess, 2015. 19(2).

Mant J. Systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis of diagnosis of heart failure, with modelling of implications of different diagnostic strategies in primary care. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13(32):232.

Meads C. Positron emission tomography/computerised tomography imaging in detecting and managing recurrent cervical cancer: systematic review of evidence, elicitation of subjective probabilities and economic modelling. Health Technol Assess. 2013;17(12):323.

Meads, C. Sentinel lymph node status in vulval cancer: systematic reviews of test accuracy and decision-analytic model-based economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess, 2013. 17(60).

Mowatt, G. Optical coherence tomography for the diagnosis, monitoring and guiding of treatment for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess, 2014. 18(69).

Mowatt G. The diagnostic accuracy and cost-effectiveness of magnetic resonance spectroscopy and enhanced magnetic resonance imaging techniques in aiding the localisation of prostate abnormalities for biopsy: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2013;17(20):281.

Mowatt G. Systematic review of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of photodynamic diagnosis and urine biomarkers (FISH, ImmunoCyt, NMP22) and cytology for the detection and follow-up of bladder cancer. Health Technol Assess. 2010;14(4):356.

Pandor A. Diagnostic management strategies for adults and children with minor head injury: a systematic review and an economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2011;15(27):202.

Waugh, N. Faecal calprotectin testing for differentiating amongst inflammatory and non inflammatory bowel diseases: systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess, 2013. 17(55).

Westwood M. A systematic review and economic evaluation of new-generation computed tomography scanners for imaging in coronary artery disease and congenital heart disease: Somatom Definition Flash, Aquilion ONE, Brilliance iCT and Discovery CT750 HD. Health Technol Assess. 2013;17(9):243.

Westwood M. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound using SonoVue® (sulphur hexafluoride microbubbles) compared with contrast-enhanced computed tomography and contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging for the characterisation of focal liver lesions and detection of liver metastases: a systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2013;17(16):243.

Westwood M. High-sensitivity troponin assays for the early rule-out or diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction in people with acute chest pain: a systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2015;19(44):145.

Deshpande, S. Rapid fetal fibronectin testing to predict preterm birth in women with symptoms of premature labour: a systematic review and cost analysis. Health Technology Assessment, 2013. 17(40).

Whiting PF. QUADAS-2: A Revised Tool for the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):529–36.

Mosterd A. Classification of Heart Failure in Population Based Research: An Assessment of Six Heart Failure Scores. Eur J Epidemiol. 1997;13(5):491–502.

Lijmer JG, Leeflang M, Bossuyt PM. Proposals for a phased evaluation of medical tests. Med Decis Making. 2009;29(5):E13–21.

Ferrante di Ruffano L, Deeks JJ. Test-treatment RCTs are sheep in wolves' clothing (Letter commenting on: J Clin Epidemiol. 2014; 67: 612–21). J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;69:266–7.

Lord SJ, Irwig L, Simes RJ. When Is Measuring Sensitivity and Specificity Sufficient To Evaluate a Diagnostic Test, and When Do We Need Randomized Trials? Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(11):850–5.

Merlin T. The “Linked Evidence Approach” to assess medical tests: a critical analysis. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2013;29(03):343–50.

Ferrante di Ruffano L. Assessing the value of diagnostic tests: a framework for designing and evaluating trials. BMJ. 2012;344:e686.

Severens JL. Efficient diagnostic test sequence: Applications of the probability-modifying plot. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(12):1228–37.

Halligan S. Computed tomographic colonography: assessment of radiologist performance with and without computer-aided detection. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(6):1690–9.

Nicholson KG. Randomised controlled trial and health economic evaluation of the impact of diagnostic testing for influenza, respiratory syncytial virus and Streptococcus pneumoniae infection on the management of acute admissions in the elderly and high-risk 18-to 64-year-olds. Health Technol Assess. 2014;18(36):1–274. vi-viii.

Sharples LD. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of endobronchial and endoscopic ultrasound relative to surgical staging in potentially resectable lung cancer: results from the ASTER randomised controlled trial. Health Technol Assess. 2012;16(18):1–75. iii-iv.

Goodacre S. The RATPAC (Randomised Assessment of Treatment using Panel Assay of Cardiac markers) trial: a randomised controlled trial of point-of-care cardiac markers in the emergency department. Health Technol Assess. 2011;15(23):iii–xi. 1-102.

Little P. Dipsticks and diagnostic algorithms in urinary tract infection: development and validation, randomised trial, economic analysis, observational cohort and qualitative study. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13(19):iii. -iv, ix-xi, 1-73.

Daniels J. Rapid testing for group B streptococcus during labour: a test accuracy study with evaluation of acceptability and cost-effectiveness. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13(42):1–154. iii-iv.

Collinson P. Randomised assessment of treatment using panel assay of cardiac markers–contemporary biomarker evaluation (RATPAC CBE). Health Technol Assess. 2013;17(15):v–vi. 1-122.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This project was part-funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care Research (SPCR) (Project No. 269). Bethany Shinkins is supported by the NIHR Diagnostic Evidence Co-operative (DEC) Leeds. Yaling Yang is funded by the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (BRC). Lucy Abel is jointly funded by the NIHR Research Capacity Fund (RCF) and the NIHR DEC Oxford. Thomas Fanshawe is partly supported by the NIHR DEC Oxford. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset generated and analysed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on request at b.shinkins@leeds.ac.uk.

Authors’ contributions

BS and TF carried out the screening, data extraction and analysis. Any disagreements were resolved by YY and LA. BS and TF drafted the manuscript, and LA and YY provided edits, comments and feedback at all stages of drafting. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This is a secondary analysis of existing data and therefore no ethical approval was required.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Inclusion criteria and data extraction details. Initial screening criteria and the data extracted from reports meeting the inclusion criteria. (DOCX 16 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Shinkins, B., Yang, Y., Abel, L. et al. Evidence synthesis to inform model-based cost-effectiveness evaluations of diagnostic tests: a methodological review of health technology assessments. BMC Med Res Methodol 17, 56 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-017-0331-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-017-0331-7