Abstract

Background

Due to limitations associated with clopidogrel following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), other newer oral anti-platelet agents are being studied. We aimed to systematically carry out a direct comparison of outcomes observed with prasugrel versus clopidogrel following PCI.

Methods

Common online searched databases (The Cochrane library, EMBASE, MEDLINE and Google scholar) were used to retrieve relevant publications. Primary endpoints were the adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Secondary outcomes were the bleeding events. This analysis was carried out by RevMan 5.3, whereby odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were considered as the statistical parameters.

Results

Eight studies with a total number of 18,122 participants were included in this direct analysis. Prasugrel was associated with significantly lower adverse cardiovascular outcomes in comparison to clopidogrel following PCI. All-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, stroke, stent thrombosis and major adverse cardiac events were all significantly lower with prasugrel (OR: 0.47, 95% CI: 0.35–0.63; P = 0.0001), (OR: 0.68, 95% CI: 0.57–0.80; P = 0.00001), (OR: 0.60, 95% CI: 0.38–0.96; P = 0.03), (OR: 0.46, 95% CI: 0.30–0.72; P = 0.0006) and (OR: 0.61, 95% CI: 0.53–0.70; P = 0.00001) respectively.

When the bleeding outcomes were analyzed, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) defined major and minor bleeding were not significantly different (OR: 0.91, 95% CI: 0.66–1.27; P = 0.59) and (OR: 1.16, 95% CI: 0.85–1.59; P = 0.35) respectively. However, the combined ‘all bleeding events’ was significantly higher with prasugrel (OR: 1.32, 95% CI: 1.03–1.70; P = 0.03), but when patients with STEMI and those undergoing elective PCI were separately analyzed, no significant difference in overall bleeding was observed.

Conclusion

Adverse cardiovascular outcomes were significantly lower with the use of prasugrel in comparison to clopidogrel following PCI. In addition, TIMI defined major and minor bleeding were not significantly different showing prasugrel to be well-tolerated following PCI especially in patients with acute coronary syndrome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The new anti-platelet agent prasugrel has been approved for use after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Ending of the year 2017 has witnessed many research articles still focusing on anti-platelet agents following PCI [1, 2]. Due to limitations associated with clopidogrel, other newer oral anti-platelet agents which could potentially replace clopidogrel are presently still being studied.

Several recently published meta-analyses comparing prasugrel with clopidogrel are available in MEDLINE and other electronic databases. However, when those research were deeply assessed, several limitations were observed. To be clear, almost all of the meta-analyses compared clopidogrel versus a combination of prasugrel and ticagrelor [3]. For example, in 2013, a meta-analysis compared newer potential anti-platelet agents (prasugrel and ticagrelor combined together) with clopidogrel following PCI [4]. Similarly in 2015, another meta-analysis involving only 4 randomized controlled trials again compared newer oral P2Y12 inhibitors (prasugrel and ticagrelor) with clopidogrel [5].

Because data on this aspect were limited, indirect comparisons were also made through network meta-analyses [6]. Fortunately, one meta-analysis at least compared clopidogrel with prasugrel (without the inclusion of other newer oral P2Y12 inhibitors) [7]. However, a major shortcoming was the fact that a detailed comparison of bleeding events and other adverse cardiovascular outcomes were not carried out.

Therefore, in this analysis, we aimed to systematically carry out a detailed direct comparison of outcomes observed with prasugrel versus clopidogrel following PCI.

Methods

Searched databases and searched strategies

Common online searched databases (The Cochrane library, EMBASE, MEDLINE and Google scholar) were used to retrieve relevant publications.

Official websites of several cardiology journals were also carefully checked for relevant publications.

The following searched terms were used to retrieve English publications:

Prasugrel and clopidogrel; Oral P2Y12 inhibitors and clopidogrel; Prasugrel and percutaneous coronary intervention; Prasugrel and coronary angioplasty; Clopidogrel, prasugrel and percutaneous coronary intervention; Clopidogrel, prasugrel and PCI; Clopidogrel, prasugrel and acute coronary syndrome/ACS.

The above-mentioned searched databases were filtered for relevant publications, and those which were found important were at first saved in a specific folder to be further reviewed based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Selection of relevant publications was based on the following inclusion criteria:

-

(a)

Randomized controlled trials or observational studies; (b) Comparing prasugrel versus clopidogrel following PCI; (c) Reporting adverse cardiovascular and bleeding outcomes among their clinical endpoints.

Publications were reviewed and then rejected based on the following exclusion criteria:

-

(a)

They were non-English publications (it should be noted that non-English publications were excluded since the authors would not be able to fully understand the language and important information would be ignored or missed and inappropriate data would be included); (b) Case-control studies, review articles, or letter to editors; (c) The studies involved patients who were not undergoing PCI; (d) They compared prasugrel with clopidogrel, however, PCI was not involved; (e) They did not report adverse cardiovascular and bleeding outcomes; (f) They were duplicated studies; (g) They involved switching from clopidogrel to prasugrel or vice-versa (crossing over).

Types of participants, outcomes, definitions and follow-ups

Participants who underwent PCI were included in this analysis: patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) especially ST segment elevated myocardial infarction (STEMI) or patients who were candidates for elective PCI were included.

The primary endpoints were the adverse cardiovascular outcomes:

All-cause mortality; Cardiovascular death; Myocardial infarction (MI); Stroke; Stent thrombosis; Repeated revascularization; Major adverse cardiac events (including death, MI, revascularization/stroke).

The secondary endpoints were the bleeding outcomes:

‘All bleeding events’ was defined as any possible type of bleeding which was reported; Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) defined major bleeding [8]; TIMI defined minor bleeding [8].

The types of participants, the outcomes which were reported in each study as well as the follow-up periods were listed in Table 1.

Data extraction and quality assessment and statistical analysis

Two authors (PKB and FH) independently reviewed the searched databases and extracted data from relevant publications.

The following data were extracted from the studies:

Total number of participants who were treated by prasugrel and clopidogrel respectively; The baseline features and the types of participants; The loading and maintenance dosages of prasugrel and clopidogrel; The methodological qualities of the trials; The adverse cardiovascular and bleeding outcomes as well as the corresponding follow-up periods which were reported.

After data extraction, data were further cross-checked. Any disagreement was resolved by consensus.

The methodological quality of the trials were also assessed based on the criteria set by the Cochrane collaboration [9]. A grade ranging from A (lowest risk of bias) to E (highest risk of bias) was allotted to each trial based on the assessment.

This analysis was carried out by RevMan 5.3 (latest version), whereby odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were considered as the statistical parameters.

Heterogeneity which is a common feature in meta-analyses, was assessed by:

(a) The Q statistic test whereby a P value less or equal to 0.05 was considered as statistically significant; (b) The I2 statistic test whereby heterogeneity increased with an increasing I2 value.

A fixed (I2 < 50%) or a random (I2 > 50%) effects model was used based on the I2 value which signified heterogeneity.

In addition, sensitivity analysis was carried out by a method of exclusion.

Publication bias was also assessed through funnel plots.

Results

Searched outcomes

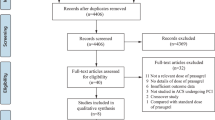

The PRISMA guideline was followed [10]. This electronic search resulted in a total number of 2949 publications. After a careful assessment of the titles and the abstracts, 2794 irrelevant publications were eliminated.

Among the remaining 155 articles, further elimination was carried out (following a second review) based on the following criteria:

They were meta-analyses (7); They were review articles (4); They were case-control studies (3); They were letter to editors (3); They were not associated with PCI (2); They involved crossing over of drugs (switching from clopidogrel to prasugrel or vice versa) [8]; They reported platelet reactivity as outcomes (11); They were duplicated studies (109).

Finally, 8 trials [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18] were included in this analysis as shown in Fig. 1.

General features of the studies

A total number of 18,122 participants were included in this direct analysis whereby 7051 participants were treated by prasugrel and 11,071 participants were treated by clopidogrel. The patients’ enrollment period varied from years 2003 and 2012. The general features of the studies were listed in Table 2.

Based on the assessment of the methodological quality of the trials, a grade was allotted to each of the trials as shown in Table 2.

All the patients received aspirin along with a loading dose of either prasugrel (60 mg in most of the cases) or clopidogrel (300 or 600 mg) prior to PCI. Following PCI, aspirin and either prasugrel (10 mg) or clopidogrel (75 mg or 150 mg) were continually used during the follow-up periods as shown in Table 3.

Baseline features of the studies

The baseline features of the participants have been listed in Table 4. The average age varied from 56 years to 65.8 years. Male participants were predominant in both groups. The percentage of participants with risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, smoking history have been listed in Table 4. According to the baseline features, there was no significant difference between participants who were treated by prasugrel or clopidogrel following PCI.

Adverse cardiovascular outcomes observed with prasugrel versus clopidogrel following PCI

Results of this analysis showed prasugrel to be associated with significantly lower adverse cardiovascular outcomes in comparison to clopidogrel following PCI. All-cause mortality, MI, stroke, stent thrombosis and MACEs were significantly lower with prasugrel (OR: 0.47, 95% CI: 0.35–0.63; P = 0.0001), (OR: 0.68, 95% CI: 0.57–0.80; P = 0.00001), (OR: 0.60, 95% CI: 0.38–0.96; P = 0.03, OR: 0.46, 95% CI: 0.30–0.72; P = 0.0006) and (OR: 0.61, 95% CI: 0.53–0.70; P = 0.00001) respectively as shown in Fig. 2. Repeated revascularization was not significantly different (OR: 0.92, 95% CI: 0.80–1.06; P = 0.25) (Fig. 2).

When participants which were extracted only from randomized controlled trials were assessed, all-cause mortality favored prasugrel (OR: 0.70, 95% CI: 0.47–1.05; P = 0.09), with a P value approaching statistical significance. Prasugrel was still associated with lower MI (OR: 0.73, 95% CI: 0.59–0.90; P = 0.003), stent thrombosis (OR: 0.49, 95% CI: 0.32–0.77; P = 0.002) and MACEs (OR: 0.74, 95% CI: 0.61–0.88; P = 0.0007).

The analysis which has been carried out above, included patients with STEMI undergoing PCI and other patients undergoing elective PCI.

When patients with ACS (mostly STEMI) were separately analyzed, all-cause mortality, MI, stroke, stent thrombosis and MACEs were still significantly lower with prasugrel as compared to clopidogrel (OR: 0.49, 95% CI: 0.28–0.85; P = 0.01), (OR: 0.68, 95% CI: 0.57–0.81; P = 0.0001), (OR: 0.55, 95% CI: 0.34–0.89; P = 0.01), (OR: 0.47, 95% CI: 0.29–0.78; P = 0.003) and (OR: 0.59, 95% CI: 0.42–0.82; P = 0.002) respectively as shown in Figs. 3 and 4.

Bleeding outcomes observed between prasugrel versus clopidogrel following PCI

When the bleeding outcomes were analyzed, TIMI defined major and minor bleeding were not significantly different (OR: 0.91, 95% CI: 0.66–1.27; P = 0.59) and (OR: 1.16, 95% CI: 0.85–1.59; P = 0.35) respectively as shown in Fig. 5.

However, ‘all bleeding events’ was significantly higher with prasugrel (OR: 1.32, 95% CI: 1.03–1.70; P = 0.03) as shown in Fig. 6.

When we included only participants which were obtained from randomized controlled trials, TIMI defined major (OR: 0.91, 95% CI: 0.66–1.27; P = 0.59) and minor (OR: 1.16, 95% CI: 0.85–1.59; P = 0.35) bleedings were still similarly manifested with prasugrel and clopidogrel.

In patients with STEMI, TIMI defined major bleeding, and TIMI defined minor bleeding were also not significantly different (OR: 0.90, 95% CI: 0.64–1.26; P = 0.53) and (OR: 1.22, 95% CI: 0.62–2.39; P = 0.56) respectively as shown in Figs. 3 and 4. Even if ‘all bleeding events’ was significantly higher in these patients with STEMI who underwent PCI, (OR: 1.31, 95% CI: 0.96–1.77; P = 0.09), the result was not statistically significant as shown in Fig. 4.

In those patients without STEMI who underwent elective PCI, TIMI defined major, minor and ‘all bleeding events’ were not significantly different (OR: 1.21, 95% CI: 0.31–4.73; P = 0.79), (OR: 3.62, 95% CI: 0.64–20.35; P = 0.14) and (OR: 1.35, 95% CI: 0.80–2.28; P = 0.26) respectively as shown in Fig. 7.

Sensitivity analysis was also carried out without any significantly different result compared to the main analysis. Consistent results were obtained throughout all the subgroups.

Publication bias

This research analysis consisted of only eight studies. Funnel plots were most appropriate to represent publication bias for similar meta-analyses with a small number of studies. The funnel plot which was generated from Revman software showed low evidence of publication bias as shown in Fig. 8.

Discussion

Prasugrel is a new anti-platelet agent which might potentially replace clopidogrel following PCI [19, 20]. In this analysis, a direct detailed systematical comparison was carried out between prasugrel and clopidogrel following coronary angioplasty.

The current results showed prasugrel to be significantly better than clopidogrel in terms of efficacy whereby mortality, MACEs, stroke and stent thrombosis were significantly reduced following PCI. TIMI defined major and minor bleeding were similarly manifested with prasugrel and clopidogrel. However, the combination of other types of bleeding which was defined as ‘all bleeding events’ was significantly higher with prasugrel, but when STEMI patients and those patients who underwent elective PCI were separately analyzed, no significant bleeding event was reported between prasugrel and clopidogrel.

This analysis showed robust results in comparison to another recently published meta-analysis [7]. Even though the current results were supported by the previous analysis (by Chen et al.), the latter involved several possible limitations. First of all, even though their analysis was based on patients post PCI, trials which did not involve patients who were revascularized by PCI were also included, contributing to its high total number of patients [21, 22]. In addition, trials which involved switching from clopidogrel to prasugrel or vice versa were also included [22]. Also, detailed outcomes were not assessed and the results which were reported showed an extremely high level of heterogeneity (up to 93%) in several subgroups [7]. The main strength of this current analysis was that it successfully resolved those flaws and limitations to provide a new analysis with robust results, with low heterogeneity in several of the subgroups, and reported a detailed analysis of the cardiovascular and bleeding outcomes.

Another analysis which was published on this aspect, involved a combination of prasugrel and ticagrelor which we think would be unfair to represent a result specifically based on prasugrel since it was associated with a combination of two anti-platelet agents [5].

In a Veterans Affairs population, prasugrel was proven to be significantly better compared to clopidogrel post PCI in terms of adverse cardiovascular events supporting the results of this analysis. Bleeding events were also not significantly higher [23].

In addition, a TRial to assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by optimizing platelet inhibitioN with prasugrel (TRITON)–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 38 Sub-study also showed results which supported this current analysis whereby prasugrel reduced ischemic events in comparison to clopidogrel [24]. Other studies have shown prasugrel to be even better than doubling the dosage of clopidogrel following stenting [25].

Furthermore, a retrospective study which compared prasugrel with clopidogrel in patients with ACS following coronary stenting also supported the current results showing significantly lower MI 1 year post PCI. The rate of minimal hemorrhage was higher with prasugrel but however, mortality was similar with both anti-platelet agents [26].

Another retrospective study showed prasugrel and clopidogrel to be similar in terms of adverse outcomes and bleeding events and the authors concluded that prasugrel was equally effective and safe [27]. This result was different from ours in terms of efficacy. But, the retrospective study was based on one single center whereas our current analysis involving mainly randomized patients from several larger trials, is believed to represent a better result.

However, the management of ACS does not only depend on anti-platelet agents. We should also emphasize on recent guidelines about how to manage patients with STEMI and NSTEMI. In this current analysis, more than 90% of the patients had STEMI whereas the remaining were NSTEMI patients. The 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction gives a detailed explanation and treatment strategies of patients with STEMI [28] whereas the 2012 ACCF/AHA focused on the update incorporated into the ACCF/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina and non-STEMI [29].

It should also be noted that diabetes mellitus and the associated medications might further influence the results of this analysis. In this analysis, each study included an average of 9.70 to 42.7% of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. However, a separate analysis of prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with diabetes mellitus was not possible because the trials did not report clinical outcomes and events separately for this particular subgroup of patients.

At last, it should be noted that incretin, a newer hypoglycemic drug, might also affect the prognosis of patients with diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease. The effects of incretin treatment on cardiovascular outcomes in diabetic patients with STEMI [30] and NSTEMI [31] have previously been studied. However, in this current analysis, we were unable to assess the percentage of STEMI and NSTEMI patients on incretin treatment.

Limitations

Even if the total number of patients were sufficient to reach a fair conclusion, several different subgroups reported less patients because the adverse cardiovascular outcomes and bleeding events were not reported in all of the trials; Different trials had different follow-up periods (1 month, 1 year to 5 years), and the follow-up periods were not taken into consideration; In addition, studies with planned PCI and ACS were mixed and analyzed at first; The other anti-platelet agents such as glycoprotein IIb/IIIa and double dose clopidogrel (150 mg instead of 75 mg), as well as the loading dose of prasugrel and clopidogrel which were different in certain studies might have influenced the results which were obtained; Moreover, publication bias was represented by funnel plots which were generated through the RevMan software. Any other additional statistical test was not carried out because the volume of studies was not sufficient.

Conclusions

Adverse cardiovascular outcomes were significantly lower with the use of prasugrel in comparison to clopidogrel following PCI. In addition, TIMI defined major and minor bleeding were not significantly different showing prasugrel to be well-tolerated following PCI especially in patients with ACS. Future studies should be based on patients with diabetes mellitus.

Abbreviations

- ACS:

-

Acute coronary syndrome

- MACEs:

-

Major adverse cardiac events

- PCI:

-

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- TIMI:

-

Thrombolysis in myocardial infarction

References

Rodriguez AE, Rodriguez-Granillo AM, Ascarrunz SD, Peralta-Bazan F, Cho MY. Did Prasugrel and Ticagrelor offer the same benefit in patients with acute coronary syndromes after percutaneous coronary interventions compared to Clopidogrel? Insights from randomized clinical trials, registries and meta-analysis. Curr Pharm Des. 2018; https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612824666180108121834.

Cherepanov V, Fortmann SD, Kim MH, Marciniak TA, Litvinov O, Mihalev K, Serebruany VL. Annual adverse event profiles after clopidogrel, prasugrel, and ticagrelor in the Food and Drug Administration adverse event reporting system. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjcvp/pvx038.

Tarantini G, Ueshima D, D'Amico G, Masiero G, Musumeci G, Stone GW, Brener SJ. Efficacy and safety of potent platelet P2Y12 receptor inhibitors in elderly versus nonelderly patients with acute coronary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am Heart J. 2018;195:78–85.

Aradi D, Komócsi A, Vorobcsuk A, Serebruany VL. Impact of clopidogrel and potent P2Y 12 -inhibitors on mortality and stroke in patients with acute coronary syndrome or undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Haemost. 2013;109(1):93–101.

Bavishi C, Panwar S, Messerli FH, Bangalore S. Meta-analysis of comparison of the newer oral P2Y12 inhibitors (Prasugrel or Ticagrelor) to Clopidogrel in patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116(5):809–17.

Chatterjee S, Ghose A, Sharma A, Guha G, Mukherjee D, Frankel R. Comparing newer oral anti-platelets prasugrel and ticagrelor in reduction of ischemic events-evidence from a network meta-analysis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2013;36(3):223–32.

Chen HB, Zhang XL, Liang HB, Liu XW, Zhang XY, Huang BY, Xiu J. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing risk of major adverse cardiac events and bleeding in patients with Prasugrel versus Clopidogrel. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116(3):384–92.

Kikkert WJ, van Geloven N, van der Laan MH, Vis MM, Baan J Jr, Koch KT, Peters RJ, de Winter RJ, Piek JJ, Tijssen JG, Henriques JP. The prognostic value of bleeding academic research consortium (BARC)-defined bleedingcomplications in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a comparison with the TIMI (thrombolysis in myocardial infarction), GUSTO (global utilization of streptokinase and tissue plasminogen activator for occluded coronary arteries), and ISTH (international society on thrombosis and Haemostasis) bleeding classifications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(18):1866–75.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcareinterventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700.

Brener SJ, Oldroyd KG, Maehara A, El-Omar M, Witzenbichler B, Xu K, Mehran R, Gibson CM, Stone GW. Outcomes in patients with ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction treated with clopidogrel versus prasugrel (from the INFUSE-AMI trial). Am J Cardiol. 2014;113(9):1457–60.

Wiviott SD, Antman EM, Winters KJ, Weerakkody G, Murphy SA, Behounek BD, Carney RJ, Lazzam C, McKay RG, McCabe CH, Braunwald E. JUMBO-TIMI 26 investigators. Randomized comparison of prasugrel (CS-747, LY640315), a novel thienopyridine P2Y12 antagonist, with clopidogrel in percutaneous coronary intervention: results of the joint utilization of medications to block platelets optimally (JUMBO)-TIMI 26 trial. Circulation. 2005;111(25):3366–73.

Saito S, Isshiki T, Kimura T, Ogawa H, Yokoi H, Nanto S, Takayama M, Kitagawa K, Nishikawa M, Miyazaki S, Nakamura M. Efficacy and safety of adjusted-dose prasugrel compared with clopidogrel in Japanese patientswith acute coronary syndrome: the PRASFIT-ACS study. Circ J. 2014;78(7):1684–92.

Wiviott SD, Trenk D, Frelinger AL, O'Donoghue M, Neumann FJ, Michelson AD, Angiolillo DJ, Hod H, Montalescot G, Miller DL, Jakubowski JA, Cairns R, Murphy SA, McCabe CH, Antman EM, Braunwald E. PRINCIPLE-TIMI 44 investigators. Prasugrel compared with high loading- and maintenance-dose clopidogrel in patients with planned percutaneous coronary intervention: the Prasugrel in comparison to Clopidogrel for inhibition of platelet activation and aggregation-thrombolysis in myocardial infarction 44 trial. Circulation. 2007;116(25):2923–32.

Dridi NP, Johansson PI, Clemmensen P, Stissing T, Radu MD, Qayyum A, Pedersen F, Helqvist S, Saunamäki K, Kelbæk H, Jørgensen E, Engstrøm T, Holmvang L. Prasugrel or double-dose clopidogrel to overcome clopidogrel low-response--the TAILOR (thrombocytes and IndividuaLization of ORal antiplatelet therapy in percutaneous coronaryintervention) randomized trial. Platelets. 2014;25(7):506–12.

Jackson LR 2nd, Ju C, Zettler M, Messenger JC, Cohen DJ, Stone GW, Baker BA, Effron M, Peterson ED, Wang TY. Outcomes of patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention receiving an oral anticoagulant and dual antiplatelet therapy: a comparison of Clopidogrel versus Prasugrel from the TRANSLATE-ACS study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8(14):1880–9.

Trenk D, Stone GW, Gawaz M, Kastrati A, Angiolillo DJ, Müller U, Richardt G, Jakubowski JA, Neumann FJ. A randomized trial of prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with high platelet reactivity on clopidogrel after elective percutaneous coronary intervention with implantation of drug-elutingstents: results of the TRIGGER-PCI (testing platelet reactivity in patients undergoing ElectiveStent placement on Clopidogrel to guide alternative therapy with Prasugrel) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(24):2159–64.

Montalescot G, Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, Murphy SA, Gibson CM, McCabe CH, Antman EM. TRITON-TIMI 38 investigators. Prasugrel compared with clopidogrel in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventionfor ST-elevation myocardial infarction (TRITON-TIMI 38): double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9665):723–31.

Damman P, Varenhorst C, Koul S, Eriksson P, Erlinge D, Lagerqvist B, James SK. Treatment patterns and outcomes in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention treated with prasugrel or clopidogrel (from the Swedish coronary angiography and angioplasty registry [SCAAR]). Am J Cardiol. 2014;113(1):64–9.

Bundhun PK, Shi JX, Huang F. Head to head comparison of Prasugrel versus Ticagrelor in patients with acute coronary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2017;18(1):80.

Roe MT, Goodman SG, Ohman EM, Stevens SR, Hochman JS, Gottlieb S, Martinez F, Dalby AJ, Boden WE, White HD, Prabhakaran D, Winters KJ, Aylward PE, Bassand JP, McGuire DK, Ardissino D, Fox KA, Armstrong PW. Elderly patients with acute coronary syndromes managed without revascularization: insights into the safety of long-term dual antiplatelet therapy with reduced-dose prasugrel versus standard-dose clopidogrel. Circulation. 2013;128(8):823–33.

Montalescot G, Sideris G, Cohen R, Meuleman C, Bal dit Sollier C, Barthélémy O, Henry P, Lim P, Beygui F, Collet JP, Marshall D, Luo J, Petitjean H, Drouet L. Prasugrel compared with high-dose clopidogrel in acute coronary syndrome. The randomised, double-blind ACAPULCO study. Thromb Haemost. 2010;103(1):213–23.

Khatri S, Pierce T. Comparing prasugrel to twice daily clopidogrel post percutaneous coronary intervention in a veterans affairs population. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72(17 Suppl 2):S98–S103.

Pride YB, Wiviott SD, Buros JL, Zorkun C, Tariq MU, Antman EM, Braunwald E, Gibson CM, TIMI Study Group. Effect of prasugrel versus clopidogrel on outcomes among patients with acute coronarysyndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention without stent implantation: a TRial to assess improvement in therapeutic outcomes by optimizing platelet inhibitioN with prasugrel (TRITON)-thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) 38 substudy. Am Heart J. 2009;158(3):e21–6.

Alexopoulos D, Dimitropoulos G, Davlouros P, Xanthopoulou I, Kassimis G, Stavrou EF, Hahalis G, Athanassiadou A. Prasugrel overcomes high on-clopidogrel platelet reactivity post-stenting more effectively than high-dose (150-mg) clopidogrel: the importance of CYP2C19*2 genotyping. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4(4):403–10.

Lalor N, Rodríguez L, Elissamburu P, Filipini E, Conde D, Nau G, Cura F, Trivi M. Clopidogrel versus prasugrel in acute coronary syndrome treated with coronary angioplasty. Medicina (B Aires). 2015;75(4):207–12.

Wang A, Lella LK, Brener SJ. Efficacy and safety of Prasugrel compared with Clopidogrel for patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Ther. 2016;23(6):e1637–43.

Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, Crea F, Goudevenos JA, Halvorsen S, Hindricks G, Kastrati A, Lenzen MJ, Prescott E, Roffi M, Valgimigli M, Varenhorst C, Vranckx P, Widimský P, ESC Scientific Document Group. 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presentingwith ST-segment elevation: the task force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39(2):119–77.

Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, Bridges CR, Califf RM, Casey DE Jr, Chavey WE 2nd, Fesmire FM, Hochman JS, Levin TN, Lincoff AM, Peterson ED, Theroux P, Wenger NK, Wright RS, Jneid H, Ettinger SM, Ganiats TG, Philippides GJ, Jacobs AK, Halperin JL, Albert NM, Creager MA, DeMets D, Guyton RA, Kushner FG, Ohman EM, Stevenson W, Yancy CW. 2012 ACCF/AHA focused update incorporated into the ACCF/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(23):e179–347.

Marfella R, Sardu C, Balestrieri ML, Siniscalchi M, Minicucci F, Signoriello G, Calabrò P, Mauro C, Pieretti G, Coppola A, Nicoletti G, Rizzo MR, Paolisso G, Barbieri M. Effects of incretin treatment on cardiovascular outcomes in diabetic STEMI-patients with culpritobstructive and multivessel non obstructive-coronary-stenosis. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2018;10:1.

Marfella R, Sardu C, Calabrò P, Siniscalchi M, Minicucci F, Signoriello G, Balestrieri ML, Mauro C, Rizzo MR, Paolisso G, Barbieri M. Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes with non-obstructive coronary artery stenosis: effects of incretin treatment. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20(3):723–9.

Funding

This research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81560046), Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (No. 2016GXNSFAA380002), Scientific Project of Guangxi Higher Education (No. KY2015ZD028), Science Research and Technology Development Project of Qingxiu District of Nanning (No. 2016058) and Lisheng Health Foundation pilotage fund of Peking (No. LHJJ20158126).

Availability of data and materials

All data and materials used in this research are freely available in electronic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane database, Google scholar). References have been provided.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PKB and FH were responsible for the conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the initial manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content. PKB wrote the final manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authors’ information

Dr. Pravesh Kumar Bundhun (M.D) is the first author. From the Department of Cardiovascular Diseases, the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, Guangxi, China.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was not applicable for this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Bundhun, P.K., Huang, F. Post percutaneous coronary interventional adverse cardiovascular outcomes and bleeding events observed with prasugrel versus clopidogrel: direct comparison through a meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 18, 78 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-018-0820-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-018-0820-6